Cleopatra's Needle (New York) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cleopatra's Needle in

Cleopatra's Needle in

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came from the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transporting of the London obelisk. The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt,

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came from the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transporting of the London obelisk. The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt,

Even with a broken propeller, the SS ''Dessoug'' was able to make the journey to the United States. The obelisk and its 50-ton pedestal arrived at the Quarantine Station in New York in early July 1880. It took 32 horses hitched in pairs to bring it from the banks of the

Even with a broken propeller, the SS ''Dessoug'' was able to make the journey to the United States. The obelisk and its 50-ton pedestal arrived at the Quarantine Station in New York in early July 1880. It took 32 horses hitched in pairs to bring it from the banks of the

Cleopatra's Needle in

Cleopatra's Needle in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

is one of a pair of obelisks, together named Cleopatra's Needle

Cleopatra's Needles are a separated pair of ancient Egyptian obelisks now in London and New York City. The obelisks were originally made in Heliopolis (modern Cairo) during the New Kingdom period, inscribed by the 18th dynasty pharaoh Thutmose I ...

s, that were relocated from the ruins of the Caesareum of Alexandria

The Caesareum of Alexandria is an ancient temple in Alexandria, Egypt. It was conceived by Cleopatra VII of the Ptolemaic kingdom, the last pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, to honour her first known lover Julius Caesar or Mark Antony.

The edifice was f ...

in the 19th century. The 15th-century BC stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

was installed in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

, west of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, on February 22, 1881. It was secured in May 1877 by judge Elbert E. Farman, the United States Consul General

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

at Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, as a gift from the Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Kh ...

for the United States remaining a friendly neutral as the European powers – France and Britain – maneuvered to secure political control of the Egyptian government. The transportation costs were largely paid for by railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

, the eldest son of Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

.

Made of red granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

, the obelisk stands about high, weighs about 200 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s, and is inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyph

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

s. It was originally erected in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis on the orders of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

, in 1475 BC. The granite was brought from the quarries of Aswan near the first cataract of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. The inscriptions were added about 200 years later by Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, wikt:rꜥ-ms-sw, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is oft ...

to commemorate his military victories. The obelisks were moved to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and set up in the Caesareum

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete state. Today they remain "the most obvious symbol of R ...

—a temple built by Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

in honor of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

or Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

—by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

in 12 BC, during the reign of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, but were toppled some time later. This had the fortuitous effect of burying their faces and so preserving most of the hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering.

Acquisition

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came from the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transporting of the London obelisk. The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt,

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came from the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transporting of the London obelisk. The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt, Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

, to give the United States an obelisk as a gift for increased trade. Mr. Dixon, the contractor who, in 1877, arranged the transport of the London obelisk, denied the newspaper accounts.

In March 1877, Mr. Henry G. Stebbins

Col. Henry George Stebbins (September 15, 1811 – December 9, 1881) was a U.S. Representative from New York during the latter half of the American Civil War.

Early life

Stebbins was born in Ridgefield, Connecticut, to Mary Largin (1783–1874) ...

, Commissioner of the Department of Public Parks of the City of New York, undertook to secure the funding to transport the obelisk to New York. However, when railroad magnate William H. Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

was asked to head the subscription, he offered to finance the project with a donation of more than .

Stebbins then sent two acceptance letters to the Khedive through the Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

which forwarded them to Judge Farman in Cairo. Realizing that he might be able to secure one of the two remaining upright obelisks—either the mate to the Paris obelisk in Luxor or the London mate in Alexandria—Judge Farman formally asked the Khedive in March 1877, and by May 1877 he had secured the gift in writing.

Location

The obelisk was placed on an obscure site behind the museum. Henry Honeychurch Gorringe, who supervised the movement of the obelisk, William Henry Hulbert, who was involved in early development of the plan, andFrederic Edwin Church

Frederic Edwin Church (May 4, 1826 – April 7, 1900) was an American landscape painter born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters, best known for painting large landscapes, ...

, a cofounder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

and a member of the Department of Public Parks in New York City, selected the site of the obelisk in 1879. Gorringe wrote, "In order to avoid needless discussion of the subject, it was decided to maintain the strictest secrecy as to the location determined on." He noted that the prime advantage of the Knoll was its "isolation" and that it was the best site to be found inside the park, as it was quite elevated and the foundation could be firmly anchored in bedrock, lest Manhattan suffer "some violent convulsion of nature."

Importing

The formidable task of moving the obelisk from Alexandria to New York was given toHenry Honychurch Gorringe

Henry Honychurch Gorringe (August 11, 1841 – July 7, 1885) was a United States naval officer who attained national acclaim for successfully completing the removal of Cleopatra's Needle from Alexandria, Egypt to Central Park in New York Cit ...

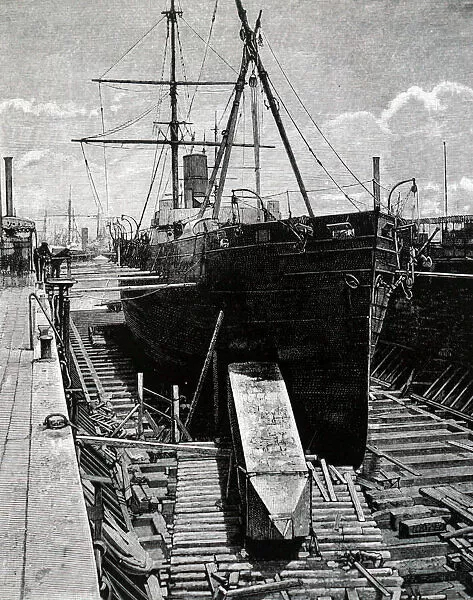

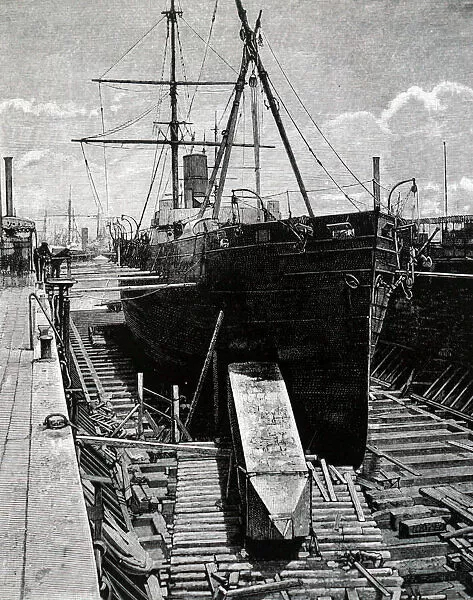

, a lieutenant commander on leave from the U.S. Navy. The 200-ton granite obelisk was first shifted from vertical to horizontal, nearly crashing to ground in the process. In August 1879 the movement process was suspended for two months because of local protests and legal challenges. Once those were resolved, the obelisk was transported seven miles to Alexandria and then put into the hold of the steamship SS '' Dessoug'', which set sail June 12, 1880. The ''Dessoug'' was heavily modified with a large hole cut into the starboard side of its bow. The obelisk was loaded through the ship's hull by rolling it upon cannonballs.

Even with a broken propeller, the SS ''Dessoug'' was able to make the journey to the United States. The obelisk and its 50-ton pedestal arrived at the Quarantine Station in New York in early July 1880. It took 32 horses hitched in pairs to bring it from the banks of the

Even with a broken propeller, the SS ''Dessoug'' was able to make the journey to the United States. The obelisk and its 50-ton pedestal arrived at the Quarantine Station in New York in early July 1880. It took 32 horses hitched in pairs to bring it from the banks of the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Queens ...

to Central Park. Railroad ramps and tracks had to be temporarily removed and the ground flattened so that the obelisk could be rolled out of the ship, whose side had been cut open once again for the purpose. The obelisk was carried up the East River and transported to a temporary location off Fifth Avenue. The final leg of the journey was made by pushing the obelisk with a steam engine across a specially built trestle bridge from Fifth Avenue to its new home on Greywacke Knoll, just across the drive from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

. It took 112 days to move the obelisk from Quarantine Station to its resting place.

Jesse B. Anthony, Grand Master of Masons in the State of New York, presided as the cornerstone for the obelisk was laid in place with full Masonic ceremony on October 2, 1880. Over 9,000 Masons paraded up Fifth Avenue from 14th Street to 82nd Street, and it was estimated that over 50,000 spectators lined the parade route. The benediction was presented by R. W. Louis C. Gerstein. The obelisk was righted by a special structure built by Henry Honychurch Gorringe. The official ceremony for erecting the obelisk was held February 22, 1881.

Hieroglyphs

The surface of the stone is heavily weathered, nearly masking the rows of Egyptian hieroglyphs engraved on all sides. Photographs taken near the time the obelisk was erected in the park show that the inscriptions or hieroglyphs, as depicted below with translation, were still quite legible and date first fromThutmosis III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

(1479–1425 BC) and then nearly 300 years later, Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, wikt:rꜥ-ms-sw, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is oft ...

the Great (1279–1213 BC). The stone had stood in the clear dry Egyptian desert air for nearly 3,000 years and had undergone little weathering. In a little more than a century in the climate of New York City, pollution and acid rain have heavily pitted its surfaces. In 2010, Dr. Zahi Hawass

Zahi Abass Hawass ( ar, زاهي حواس; born May 28, 1947) is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, serving twice. He has also worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Wes ...

sent an open letter to the president of the Central Park Conservancy and the Mayor of New York City insisting on improved conservation efforts. If they were not able to properly care for the obelisk, he threatened to "take the necessary steps to bring this precious artifact home and save it from ruin".

Buried objects

A time capsule buried beneath the obelisk contains an 1870 U.S. census, aBible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, a ''Webster's Dictionary

''Webster's Dictionary'' is any of the English language dictionaries edited in the early 19th century by American lexicographer Noah Webster (1758–1843), as well as numerous related or unrelated dictionaries that have adopted the Webster's n ...

'', the complete works of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, a guide to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, and a copy of the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

. A small box was also placed in the capsule by the man who arranged the obelisk's purchase and transportation, but its contents remain unknown.

See also

*List of Egyptian obelisks

Obelisks had a prominent role in the architecture and religion of ancient Egypt. This list contains all known remaining ancient Egyptian obelisks. The list does not include modern or pre-modern pseudo-Egyptian obelisks, such as the numerous Egyp ...

References

Further reading

* {{Authority control 15th-century BC steles Ancient Egyptian obelisks Central Park Diplomatic gifts Landmarks in New York (state) Monuments and memorials in Manhattan Obelisks in the United States Relocated buildings and structures in New York City Thutmose III 1881 establishments in New York (state) Cleopatra's Needles