Claude Pepper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Claude Denson Pepper (September 8, 1900 – May 30, 1989) was an American politician of the Democratic Party, and a spokesman for left-liberalism and the elderly. He represented

In 1934, Pepper ran for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate, challenging incumbent Park Trammell. Pepper lost to Trammell in the primary runoff 51%–49%. But Pepper was unopposed in the 1936 special election following the death of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher, and succeeded William Luther Hill, who had been appointed pending the special election. In the Senate, Pepper became a leading New Dealer and close ally of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was unusually articulate and intellectual, and, collaborating with labor unions, he was often the leader of the liberal-left forces in the Senate. His reelection in a heavily fought primary in 1938 solidified his reputation as the most prominent liberal in Congress. His campaign based on a wages-hours bill, which soon became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. He sponsored the

In 1934, Pepper ran for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate, challenging incumbent Park Trammell. Pepper lost to Trammell in the primary runoff 51%–49%. But Pepper was unopposed in the 1936 special election following the death of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher, and succeeded William Luther Hill, who had been appointed pending the special election. In the Senate, Pepper became a leading New Dealer and close ally of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was unusually articulate and intellectual, and, collaborating with labor unions, he was often the leader of the liberal-left forces in the Senate. His reelection in a heavily fought primary in 1938 solidified his reputation as the most prominent liberal in Congress. His campaign based on a wages-hours bill, which soon became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. He sponsored the

In 1962, Pepper was elected to the

In 1962, Pepper was elected to the

A number of places in Florida are named for Pepper, including the Claude Pepper Center at Florida State University (housing a

A number of places in Florida are named for Pepper, including the Claude Pepper Center at Florida State University (housing a

in JSTOR

* Clark, James C. ''Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary'' (2011) * Crispell, Brian Lewis, ''Testing the Limits: George Armistead Smathers and Cold War America'' (1999) * Danese, Tracy E. ''Claude Pepper and Ed Ball: Politics, Purpose, and Power'' (2000) * Denman, Joan E. "Senator Claude D. Pepper: Advocate of Aid to the Allies, 1939–1941", ''Florida Historical Quarterly'', vol. 83, no. 2 (Fall 2004), pp. 121–148

in JSTOR

* Finley, Keith M. ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965'' (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008). * Swint, Kerwin C., ''Mudslingers: The Twenty-five Dirtiest Political Campaigns of All Time''. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006.

Biographical Directory of the US Congress

Claude Pepper Papers at Florida State University

Claude Pepper Library

Claude Pepper Foundation

Claude Pepper Center

*

fro

Oral Histories of the American South

*

Claude D. Pepper, Late a Representative from Florida

'. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office 1990. , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Pepper, Claude 1900 births 1989 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians American anti-communists American legal scholars Baptists from Alabama Deaths from stomach cancer Democratic Party United States senators from Florida Florida lawyers Harvard Law School alumni Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Florida Democratic Party members of the Florida House of Representatives Military personnel from Alabama Opposition to Fidel Castro People from Perry, Florida People from Tallapoosa County, Alabama Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

from 1936 to 1951, and the Miami area in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from 1963 until 1989.

Born in Chambers County, Alabama

Chambers County is a county located in the east central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census the population was 34,772. Its county seat is LaFayette. Its largest city is Valley. Its name is in honor of Henry H. Chamb ...

, Pepper established a legal practice in Perry, Florida

Perry is a city in Taylor County, Florida, United States. As of 2010, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau is 7,017.

It is the county seat. The city was named for Madison Perry, fourth Governor of the State of Florida and a Confe ...

, after graduating from Harvard Law School. After serving a single term in the Florida House of Representatives, Pepper won a 1936 special election to succeed Senator Duncan U. Fletcher. Pepper became one of the most prominent liberals in Congress, supporting legislation such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) is a United States labor law that creates the right to a minimum wage, and " time-and-a-half" overtime pay when people work over forty hours a week. It also prohibits employment of minors in "opp ...

. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Pepper's conciliatory views towards the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and opposition to President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

's 1948 re-nomination engendered opposition within the party. Pepper lost the 1950 Senate Democratic primary to Congressman George Smathers

George Armistead Smathers (November 14, 1913 – January 20, 2007) was an American lawyer and politician who represented the state of Florida in the United States Senate from 1951 until 1969 and in the United States House from 1947 to 1951, as ...

, and returned to private legal practice the following year.

In 1962, Pepper won election to a newly-created district in the United States House of Representatives. He emerged as a staunch anti-Communist, and strongly criticized Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

n leader Fidel Castro. Pepper served as chairman of the House Committee on Aging, and pursued reforms to Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

and Medicare. From 1983 to 1989, he served as chairman of the powerful House Rules Committee

The Committee on Rules, or more commonly, the Rules Committee, is a committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is responsible for the rules under which bills will be presented to the House of Representatives, unlike other commit ...

. He died in office in 1989, and was honored with a state funeral. In 2000, the United States Postal Service issued a 33¢ Distinguished Americans series The Distinguished Americans series is a set of definitive stamps issued by the United States Postal Service which was started in 2000 with a 10¢ stamp depicting Joseph Stilwell. The designs of the first nine issues are reminiscent of the earlier Gr ...

postage stamp honoring Pepper.

Early life

Claude Denson Pepper was born on September 8, 1900, inChambers County, Alabama

Chambers County is a county located in the east central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census the population was 34,772. Its county seat is LaFayette. Its largest city is Valley. Its name is in honor of Henry H. Chamb ...

, the son of farmers Lena Corine Talbot (1877-1961) and Joseph Wheeler Pepper (1873-1945). Pepper was the fourth child born to his parents; the first three died in infancy. Pepper was an only child until he was ten years old; his younger siblings were Joseph, Sara and Frank. He attended school in Dudleyville and Camp Hill, and graduated from Camp Hill High School in 1917. He then operated a hat cleaning and repair business, taught school in Dothan and worked in an Ensley steel mill before beginning studies at the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publi ...

.

While in college he joined the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

for World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and served in the Student Army Training Corps (SATC, precursor to the Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in al ...

). The war ended before he saw active service, and after the SATC was disbanded, Pepper joined the ROTC. While lifting ammunition crates during a training event, Pepper suffered a double hernia

A hernia is the abnormal exit of tissue or an organ, such as the bowel, through the wall of the cavity in which it normally resides. Various types of hernias can occur, most commonly involving the abdomen, and specifically the groin. Groin herni ...

, which required surgery to correct. After graduating from the University of Alabama with his A.B.

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree in 1921, Pepper was able to use his veterans' and disability benefits to attend Harvard Law School, and he received his LL.B.

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1924.

Career

Pepper taught law at theUniversity of Arkansas

The University of Arkansas (U of A, UArk, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and the largest university in the state. Founded as Arkansas ...

(where his students included J. William Fulbright

James William Fulbright (April 9, 1905 – February 9, 1995) was an American politician, academic, and statesman who represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1945 until his resignation in 1974. , Fulbright is the longest serving chair ...

) and then moved to Perry, Florida

Perry is a city in Taylor County, Florida, United States. As of 2010, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau is 7,017.

It is the county seat. The city was named for Madison Perry, fourth Governor of the State of Florida and a Confe ...

, where he opened a law practice. Pepper was a member of the Florida Democratic Party

The Florida Democratic Party (FDP) is the affiliate of the Democratic Party in the U.S. state of Florida, headquartered in Tallahassee. Former mayor of Miami Manny Diaz Sr. is the current chair.

Andrew Jackson, the first territorial governo ...

's executive committee from 1928 to 1929.

He was elected to the Florida House of Representatives in 1928 and served from 1929 to 1931. During his term, Pepper served as chairman of the House's Committee on Constitutional Amendments. In response to the Great Depression, Governor Doyle E. Carlton proposed austerity measures including layoffs of state employees and large tax cuts. Pepper was among those who opposed Carlton's program, and popular support was with Carlton, so Pepper was among many legislators who lost when they ran for renomination in 1930.

After being defeated for reelection, Pepper moved his law practice to Tallahassee, the state capital. In 1931, he met Mildred Webster outside the governor's office. They began dating, and they married in St. Petersburg on December 29, 1936. They remained married until her death in 1979, and had no children.

Florida government

Pepper served on the Florida Board of Public Welfare from 1931 to 1932, and was a member of the Florida Board of Bar Examiners in 1933.U.S. Senate

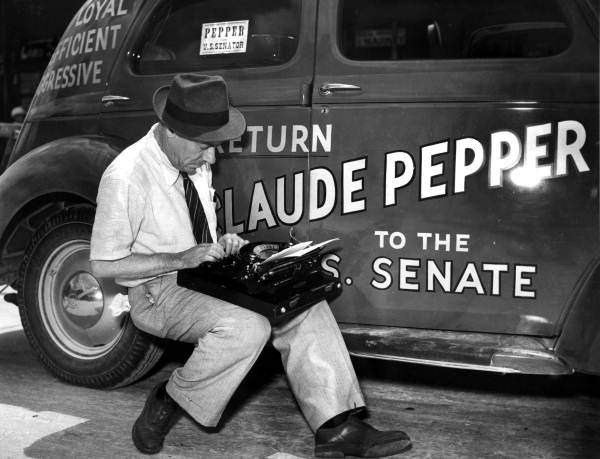

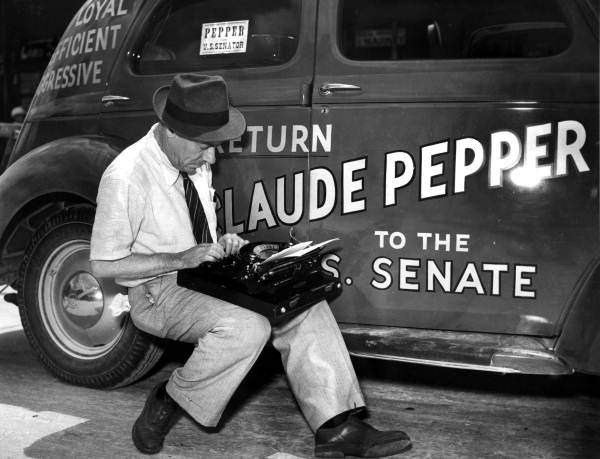

In 1934, Pepper ran for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate, challenging incumbent Park Trammell. Pepper lost to Trammell in the primary runoff 51%–49%. But Pepper was unopposed in the 1936 special election following the death of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher, and succeeded William Luther Hill, who had been appointed pending the special election. In the Senate, Pepper became a leading New Dealer and close ally of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was unusually articulate and intellectual, and, collaborating with labor unions, he was often the leader of the liberal-left forces in the Senate. His reelection in a heavily fought primary in 1938 solidified his reputation as the most prominent liberal in Congress. His campaign based on a wages-hours bill, which soon became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. He sponsored the

In 1934, Pepper ran for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate, challenging incumbent Park Trammell. Pepper lost to Trammell in the primary runoff 51%–49%. But Pepper was unopposed in the 1936 special election following the death of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher, and succeeded William Luther Hill, who had been appointed pending the special election. In the Senate, Pepper became a leading New Dealer and close ally of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was unusually articulate and intellectual, and, collaborating with labor unions, he was often the leader of the liberal-left forces in the Senate. His reelection in a heavily fought primary in 1938 solidified his reputation as the most prominent liberal in Congress. His campaign based on a wages-hours bill, which soon became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. He sponsored the Lend-Lease Act

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

. He joined other Southern senators to filibuster an anti- lynching bill in 1937, but broke with them to support anti- poll tax legislation in the 1940s.

In 1943, a confidential analysis by Isaiah Berlin of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid p ...

for the British Foreign Office described Pepper as: A loud-voiced and fiery New Deal politician. BeforeBecause of the power of the Conservative Coalition, he usually lost on domestic policy. He was, however, more successful in promoting an international foreign policy based on friendship with the Soviet Union. In 1946, Pepper appeared frequently in the national press and began to eye the 1948 presidential race. He considered running with his close friend and fellow liberal, former Vice President Henry A. Wallace, with whom he was active in the Southern Conference for Human Welfare.Pearl Harbor Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ..., he was a most ardent interventionist. He is equally Russophile and apt to be critical of British Imperial policy. He is an out and out internationalist and champion of labour and negro rights (Florida has no poll tax) and thus a passionate supporter of the Administration's more internationalist policies. He is occasionally used by the President for the purpose of sending up trial balloons in matters of foreign policy. With all these qualities, he is, in his methods, a thoroughly opportunist politician.

"Eisenhower Boom"

Pepper was re-elected in 1944. By 1947, momentum was growing for the Draft Eisenhower movement. On September 10, 1947, US GeneralDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

disclaimed any association with the movement. In mid-September 1947, US Representative W. Sterling Cole of New York voiced opposition to the nomination of Eisenhower or any other military leader, including George C. Marshall and Douglas MacArthur. In December 1947, an actor impersonating Eisenhower sang " Kiss Me Again" during a political dinner in Washington, DC, whose attendees including President Truman (Democratic incumbent) and numerous Republican potential candidates: the song's refrain ran "but it's too soon. Some time next June, ask me, ask me again, ask me, ask me again." On April 3, 1948, Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) is a liberal American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA views itself as supporting social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research, and supporting pro ...

(ADA), led by members Adolf A. Berle Jr. and Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., declared its decision to support a ticket of Eisenhower and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

.

On April 5, 1948, Eisenhower stated his position remained unchanged: he would not accept a nomination. In mid-April 1948, American labor unions had entered the debate, as William B. Green, president of the American Federation of Labor, criticized the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for support the "Eisenhower Boom".

On July 2, 1948, the White House sent George E. Allen, friend and adviser to both Truman and Eisenhower, to the general to persuade him to make yet another denial about his candidacy. On July 3, 1948, Democratic state organizations in Georgia and Virginia openly backed Eisenhower, as did former New York state court judge Jeremiah T. Mahoney. The same day, Progressive presumptive candidate Wallace scorned the Eisenhower boom's southern supporters, saying, "They have reason to believe that Ike is reactionary because of his testimony on the draft and UMT niversal Military Training" On July 4, 1948, rumors abounded, e.g., Eisenhower would accept an "honest draft" or (from the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the U ...

'') Eisenhower would accept the nomination if made by Truman himself. On July 5, 1948, a ''New York Times'' survey completed the previous day revealed that support for Eisenhower as Democratic nominee for president was "increasing among delegates", fueled by an "Anti-Truman Group" led by James Roosevelt

James Roosevelt II (December 23, 1907 – August 13, 1991) was an American businessman, Marine, activist, and Democratic Party politician. The eldest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, he served as an official Secr ...

of California, Jacob Arvey of Illinois, and William O'Dwyer

William O'Dwyer (July 11, 1890November 24, 1964) was an Irish-American politician and diplomat who served as the 100th Mayor of New York City, holding that office from 1946 to 1950.

Life and career

O'Dwyer was born in Bohola, County Mayo, Ir ...

of New York. US Senator John C. Stennis of Mississippi declared his support for Eisenhower. At 10:30 PM that night, Eisenhower issued an internal memo at Columbia for release by the university's PR director that "I will not, at this time, identify myself with any political party, and could not accept nomination for public office or participate in a partisan political contest." Support persisted nonetheless, and on July 6, 1948, a local Philadelphia group seized on Eisenhower's phrases about "political party" and "partisan political contest" and declared their continued support for him. The same day, Truman supporters expressed their satisfaction with the Eisenhower memo and confidence in the nomination. By July 7, 1948, the week before the 1948 Democratic National Convention

The 1948 Democratic National Convention was held at Philadelphia Convention Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 12 to July 14, 1948, and resulted in the nominations of President Harry S. Truman for a full term and Senator Alben W ...

, the Draft Eisenhower movement drifted onwards, despite flat denials by Eisenhower and despite public declarations of confidence by Truman and Democratic Party national chairman J. Howard McGrath. Nevertheless, 5,000 admirers gathered in front of Eisenhower's Columbia residence to ask him to run.

In 1948, Pepper supported not his friend Henry A. Wallace but Eisenhower. In fact, on July 7, 1948, Pepper went further than any other supporter with an extraordinary proposal: Senator Claude Pepper of Florida called on the Democratic party today to transform itself temporarily into a national movement, draft Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower as a "national" and hence "nonpartisan" Presidential candidate and promise him substantial control of the party's national convention opening in Philadelphia next week.Pepper managed to gain support from ADA. The Draft Ike movement gained support from the CIO, the Liberal Party of New York State, Democratic local leaders ( Jacob Arvey of Chicago,

It would be necessary, Mr. Pepper suggested, for the convention to invite General Eisenhower to write his own platform and to pick the Vice~Presidential nominee.

Moreover, the Senator said, the general should be assured that the Democrats would never make partisan claims on him, and he should be presented not as a "Democratic" candidate but the candidate of a convention "speaking not as Democrats but simply as Americans."

Frank Hague

Frank Hague (January 17, 1876 – January 1, 1956) was an American Democratic Party politician who served as the Mayor of Jersey City, New Jersey from 1917 to 1947, Democratic National Committeeman from New Jersey from 1922 until 1949, and Vice ...

of New Jersey, Mayor William O'Dwyer

William O'Dwyer (July 11, 1890November 24, 1964) was an Irish-American politician and diplomat who served as the 100th Mayor of New York City, holding that office from 1946 to 1950.

Life and career

O'Dwyer was born in Bohola, County Mayo, Ir ...

of New York City, and Mayor Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

of Minneapolis), as well as ADA leaders Leon Henderson and James Roosevelt

James Roosevelt II (December 23, 1907 – August 13, 1991) was an American businessman, Marine, activist, and Democratic Party politician. The eldest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, he served as an official Secr ...

II. Eisenhower made repeated statements that he would not accept the Democratic Party's nomination well into July, just ahead of the 1948 Democratic National Convention

The 1948 Democratic National Convention was held at Philadelphia Convention Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 12 to July 14, 1948, and resulted in the nominations of President Harry S. Truman for a full term and Senator Alben W ...

. When Eisenhower, who accepted to become president of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in January 1948) made three statements refusing the nomination during July 1948, Pepper and others gave up and provided lukewarm support to Harry S. Truman. His third and last denial, sent by telegram to Pepper, ended the "Eisenhower Boom", and delegates began to reconsider Truman. (Pepper also made a bid for presidential candidacy but withdrew it.) On the evening of July 9, 1948, Roosevelt conceded at "Eisenhower-for-President headquarters" that the general would not accept a nomination. During the convention (July 12–14, 1948) and after, concern persisted that the Eisenhower Boom had weakened Truman's hopes in the November 1948 elections.

In 1950, Pepper lost his bid for a third full term in 1950 by a margin of over 60,000 votes. Ed Ball, a power in state politics who had broken with Pepper, financed his opponent, U.S. Representative George A. Smathers. A former supporter of Pepper, Smathers repeatedly attacked "Red Pepper" for having far-left sympathies, condemning both his support for universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

and his alleged support for the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Pepper had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1945 and, after meeting Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, declared he was "a man Americans could trust."Fund, John. ''Political Journal: George Smathers, RIP'', January 24, 2007. Because of his left-of-center sympathies with people like Wallace and actor-activist Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplish ...

and because of his bright red hair, he became widely nicknamed "Red Pepper".

At a speech made on November 11, 1946, before a pro-Soviet group known as Ambijan, which supported the creation of a Soviet Jewish republic in the far east of the USSR, Pepper told his listeners that "Probably nowhere in the world are minorities given more freedom, recognition and respect than in the Soviet Union ndnowhere in the world is there so little friction, between minority and majority groups, or among minorities." Democracy was "growing" in that country, he added, and he asserted that the Soviets were making such contributions to democracy "that many who decry it might well imitate and emulate rather than despair."

Two years later, on November 21, 1948, speaking to the same group, he again lauded the Soviet Union, calling it a nation which has recognized the dignity of all people, a nation wherein discrimination against anybody on account of race is a crime, and which was in fundamental sympathy with the progress of mankind.

Communist allegations

Regarding the 1950 Florida Senate election, PresidentHarry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

called George Smathers

George Armistead Smathers (November 14, 1913 – January 20, 2007) was an American lawyer and politician who represented the state of Florida in the United States Senate from 1951 until 1969 and in the United States House from 1947 to 1951, as ...

into a meeting at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

and reportedly said, "I want you to do me a favor. I want you to beat that son-of-a-bitch Claude Pepper." Pepper had been part of an unsuccessful 1948 campaign to " dump Truman" as the Democratic presidential nominee. Smathers ran against him in the Democratic primary (which at the time in Florida was tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

, the Republican Party still being in infancy there). The contest was extremely heated, and revolved around policy issues, especially charges that Pepper represented the far left and was too supportive of Stalin. Pepper's opponents circulated widely a 49-page booklet titled ''The Red Record of Senator Claude Pepper''. Pepper was defeated in the primary by Smathers.

Law practice

Pepper returned to law practice in Miami and Washington, failing in a comeback bid to regain a Senate seat in the 1958 Democratic primary in which he challenged his former colleague, Spessard Holland. However, Pepper did carry eleven counties, including populous Dade County where he later staged a remarkable comeback.U.S. House

In 1962, Pepper was elected to the

In 1962, Pepper was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from a newly created liberal district around Miami and Miami Beach established due to population growth in the area, becoming one of very few former United States Senators in modern times (the only other examples being James Wolcott Wadsworth Jr.

James Wolcott Wadsworth Jr. (August 12, 1877June 21, 1952) was an American politician, a Republican Party (United States), Republican from New York (state), New York. He was the son of New York State Comptroller James Wolcott Wadsworth, and the ...

from New York, Hugh Mitchell from Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Alton Lennon from North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

, Garrett Withers

Garrett Lee Withers (June 21, 1884 – April 30, 1953) was an American politician and lawyer. As a Democrat, he represented Kentucky in the United States Senate and United States House of Representatives.

Withers was born on a farm in Webster Co ...

from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, and Magnus Johnson from Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

) to be elected to the House after their Senate careers. ( Matthew M. Neely from West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

and Charles A. Towne from New York via Minnesota were also elected to the House after their Senate careers, but they had been elected to the House before their Senate careers as well.)

Pepper remained a member of the House until his death in 1989, rising to chair of the powerful Rules Committee in 1983. Despite a reputation as a leftist in his youth, Pepper turned staunchly anti-communist in the last third of his life, opposing Cuban leader Fidel Castro and supporting aid to the Nicaraguan Contras. Pepper voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968

The year was highlighted by protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – " Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

* Janu ...

, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Pepper would be the only Representative from Florida who would vote in favor of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In the early 1970s, Pepper chaired the Joint House–Senate Committee on Crime; then, in 1977, he became chair of the new House Select Committee on Aging, which became his base as he emerged as the nation's foremost spokesman for the elderly, especially regarding Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

programs. He succeeded in strengthening Medicare. In 1980 the committee under Pepper's leadership initiated what became a four-year investigation into health care scams that preyed on older people; the report, published in 1984 and commonly called "The Pepper Report", was entitled "Quackery, a $10 Billion Scandal".

In the 1980s, he worked with Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He works as a private adviser and provides consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates LLC. ...

in a major reform of the Social Security system that maintained its solvency by slowly raising the retirement age, thus cutting benefits for workers retiring in their mid-60s, and in 1986 he obtained the passage of a federal law that abolished most mandatory retirement ages. In his later years, Pepper, who customarily began each day by eating a bowl of tomato soup with crackers, sported a replaced hip and hearing aids in both ears, but continued to remain an important and often lionized figure in the House.

In 1988, Pepper sponsored a legislation to create the National Center for Biotechnology Information

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) is part of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), a branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It is approved and funded by the government of the United States. The ...

(NCBI). Enacted during his final term, the NCBI has revolutionized the exchange, sharing and analysis of genetic information and aided researchers worldwide to achieve advances in medical, computational and biological sciences.

Pepper became known as the "grand old man of Florida politics". He was featured on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine in 1938 and 1983. During this time, Republicans often joked that he and House Speaker Tip O'Neill were the only Democrats who really drove President Ronald Reagan crazy.

Personal life and death

On May 26, 1989, Pepper was presented with thePresidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

by President George H. W. Bush. Four days later, Pepper died in his sleep from stomach cancer. His body lay in state for two days in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol; he was the 26th American so honored and was the last person to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda with an open casket. Pepper was buried at Oakland Cemetery in Tallahassee

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2020, the population ...

. A special election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

was held in August 1989 to fill his seat, won by Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (; born Ileana Carmen Ros y Adato, July 15, 1952) is a politician and lobbyist from Miami, Florida, who represented from 1989 to 2019. By the end of her tenure, she was the most senior U.S. Representative from Florida. She ...

, who served until retiring at the conclusion of the 115th Congress

The 115th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States of America federal government, composed of the Senate and the House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 2017, to January ...

.

Legacy

think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

devoted to intercultural dialogue in conjunction with the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations

The United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC) is an initiative that attempts to "galvanize international action against extremism" through the forging of international, intercultural and interreligious dialogue and cooperation. The Allian ...

and an institute on aging) and the Claude Pepper Federal Building in Miami, as well as several public schools. Large sections of U.S. Route 27 in Florida are named Claude Pepper Memorial Highway. Since 2002, the Democratic Executive Committee (DEC) of Lake County has held an annual "Claude Pepper Dinner" to honor Pepper's tireless support for senior citizens. The Claude Pepper Building (building number 31) at the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in the late ...

in Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda () is an unincorporated, census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located just northwest of Washington, D.C. It takes its name from a local church, the Bethesda Meeting House (1820, rebuilt 1849), which in ...

is also named for him.

Pepper's wife Mildred was well known and respected for her humanitarian work and was honored with a number of places in Florida named in her honor. A year after his passing, Claude Pepper was honored in a play written by Shepard Nevel and directed by Phillip Church. ''Pepper'' premiered in June 1990 to a full house at the Colony Theater in Miami Beach. In 1993, Bradenton, Florida actor Kelly Reynolds portrayed Pepper in several performances held at area schools, libraries and nursing homes.

Awards

In 1982, Pepper received the Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged, an annual presentation of the Jefferson Awards. In 1983, he received the Golden Plate Award of theAmerican Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

.

In 1985, the Roosevelt Institute

The Roosevelt Institute is a liberal American think tank. According to the organization, it exists "to carry forward the legacy and values of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt by developing progressive ideas and bold leadership in the service of re ...

awarded Pepper its Four Freedoms medal.

Pepper would be posthumously inducted into the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame on February 29, 2012 in a ceremony held by Florida Governor Rick Scott in the Florida State Capitol. He was one of the first three along with Mary McLeod Bethune

Mary Jane McLeod Bethune ( McLeod; July 10, 1875 – May 18, 1955) was an American educator, philanthropist, humanitarian, womanist, and civil rights activist. Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women in 1935, established the organi ...

and Charles Kenzie Steele Sr to be inducted into it.

Bibliography

* ''Eyewitness to a Century'' with Hays Gorey (1987) – an autobiographySee also

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1950–99) *List of members of the American Legion

This table provides a list of notable members of The American Legion.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

References

External links

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:American Legion, List O ...

* List of members of the House Un-American Activities Committee

This list of members of the House Un-American Activities Committee details the names of those members of the United States House of Representatives who served on the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) from its formation as the "Special ...

* Draft Eisenhower movement

Footnotes

Further reading

* Clark, James C., "Claude Pepper and the Seeds of His 1950 Defeat, 1944–1948", ''Florida Historical Quarterly'', vol. 74, no. 1 (Summer 1995), pp. 1–22in JSTOR

* Clark, James C. ''Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary'' (2011) * Crispell, Brian Lewis, ''Testing the Limits: George Armistead Smathers and Cold War America'' (1999) * Danese, Tracy E. ''Claude Pepper and Ed Ball: Politics, Purpose, and Power'' (2000) * Denman, Joan E. "Senator Claude D. Pepper: Advocate of Aid to the Allies, 1939–1941", ''Florida Historical Quarterly'', vol. 83, no. 2 (Fall 2004), pp. 121–148

in JSTOR

* Finley, Keith M. ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965'' (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008). * Swint, Kerwin C., ''Mudslingers: The Twenty-five Dirtiest Political Campaigns of All Time''. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006.

External links

Biographical Directory of the US Congress

Claude Pepper Papers at Florida State University

Claude Pepper Library

Claude Pepper Foundation

Claude Pepper Center

*

fro

Oral Histories of the American South

*

Claude D. Pepper, Late a Representative from Florida

'. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office 1990. , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Pepper, Claude 1900 births 1989 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians American anti-communists American legal scholars Baptists from Alabama Deaths from stomach cancer Democratic Party United States senators from Florida Florida lawyers Harvard Law School alumni Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Florida Democratic Party members of the Florida House of Representatives Military personnel from Alabama Opposition to Fidel Castro People from Perry, Florida People from Tallapoosa County, Alabama Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award