Class conflict on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in

In political science,

In political science,

Of all the notable figures discussed by Plutarch and Tacitus, agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus may have most challenged the upper classes and most championed the cause of the lower classes. In a speech to the common soldiery, he decried their lowly conditions:

Of all the notable figures discussed by Plutarch and Tacitus, agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus may have most challenged the upper classes and most championed the cause of the lower classes. In a speech to the common soldiery, he decried their lowly conditions:

The patrician Coriolanus, whose life

The patrician Coriolanus, whose life

Enlightenment-era historian

Enlightenment-era historian

It was with bitter sarcasm that Rousseau outlined the class conflict prevailing in his day between masters and their workmen:

It was with bitter sarcasm that Rousseau outlined the class conflict prevailing in his day between masters and their workmen:

'. Retrieved 24 November 2008. This largely happens when the members of a class become aware of their Exploitation of labour, exploitation and the conflict with another class. A class will then realize their shared interests and a common identity. According to Marx, a class will then take action against those that are exploiting the lower classes. What Marx points out is that members of each of the two main classes have interests in common. These class or collective interests are in conflict with those of the other class as a whole. This in turn leads to conflict between individual members of different classes. Marxist analysis of society identifies two main social groups: * ''Labour'' (the proletariat or workers) includes anyone who earns their livelihood by selling their labor power and being paid a wage or salary for their labor time. They have little choice but to work for capital, since they typically have no independent way to survive. * ''Capital'' (the bourgeoisie or capitalists) includes anyone who gets their income not from labor as much as from the

sex, race and class

are bound up together. Within Marxist scholarship there is an ongoing debate about these topics. According to

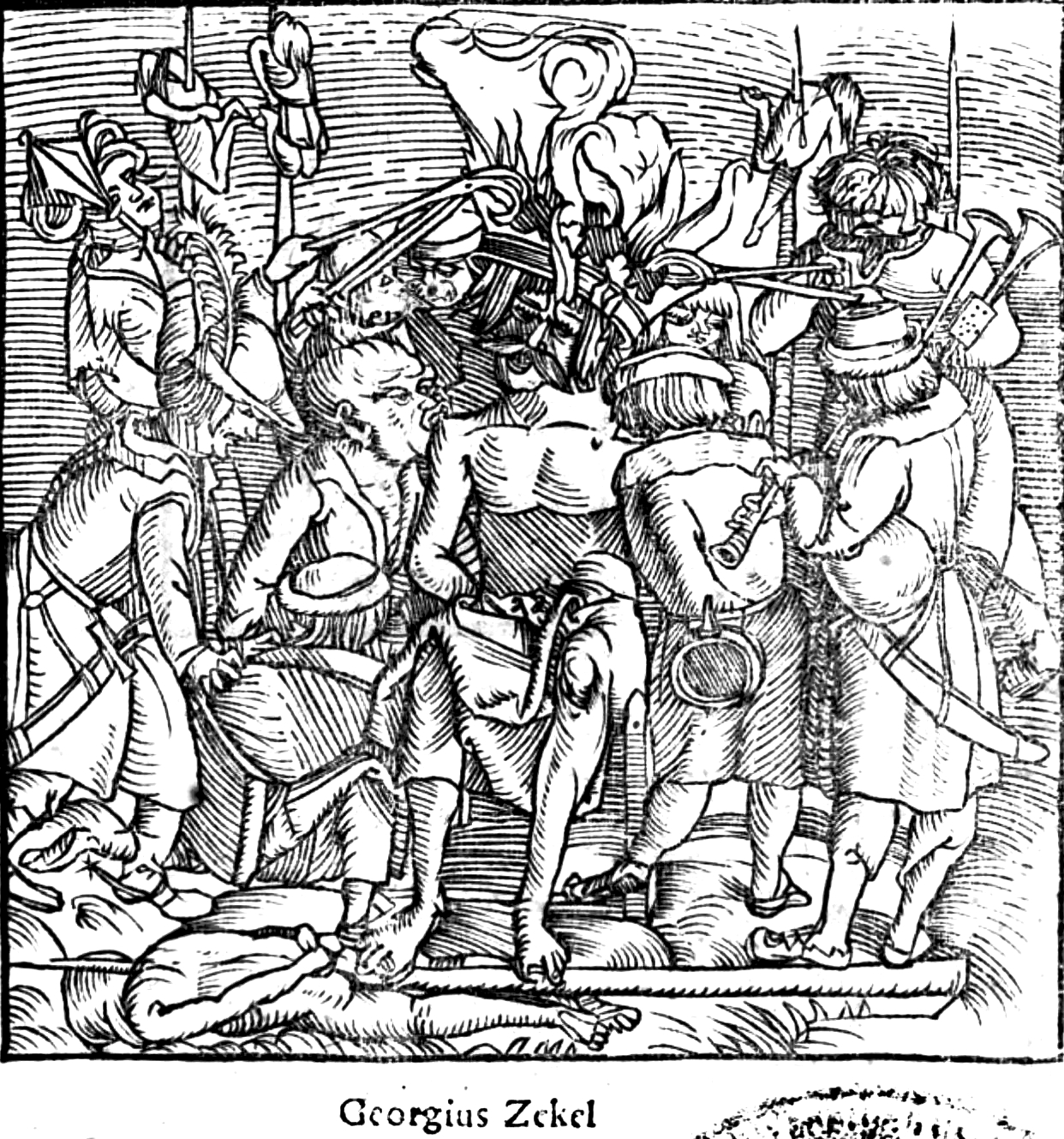

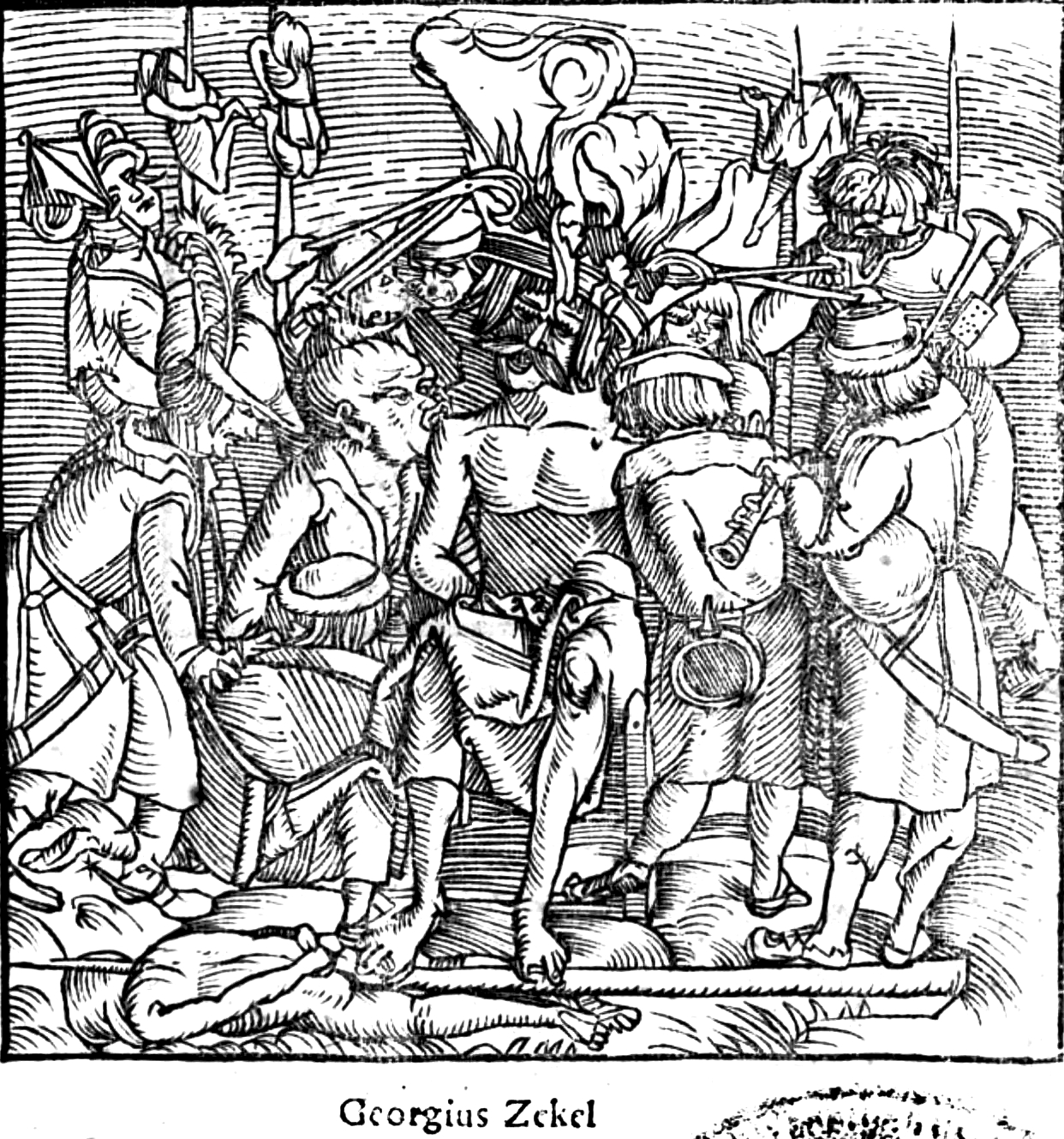

* German Peasants' War since 1524

*

* German Peasants' War since 1524

*

Class Warfare, Anarchy and the Future Society

, Journal of Futures Studies, December 2012, 17(2): 15–36 * *

2008-2010 Study: CEOs Who Fired Most Workers Earned Highest Pay

– video report by '' Democracy Now!''

How a Real Class War, Like with Guns, Could Actually Happen

'' Vice'', 26 November 2018. {{authority control Anti-capitalism Anti-fascism Conflict theory Political science Social classes Social conflict Socialism

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soc ...

because of socio-economic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their loc ...

competition among the social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inc ...

es or between rich and poor.

The forms of class conflict include direct violence such as wars for resources and cheap labor, assassinations or revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

; indirect violence such as deaths from poverty and starvation, illness and unsafe working conditions; and economic coercion such as the threat of unemployment or the withdrawal of investment capital ( capital flight); or ideologically, by way of political literature. Additionally, political forms of class warfare include legal and illegal lobbying, and bribery of legislators.

The social-class conflict can be direct, as in a dispute between labour and management such as an employer's industrial lockout of their employees in effort to weaken the bargaining power of the corresponding trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

; or indirect such as a workers' slowdown of production in protest at perceived unfair labor practices

An unfair labor practice (ULP) in United States labor law refers to certain actions taken by employers or unions that violate the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (49 Stat. 449) (also known as the NLRA and the Wagner Act after NY Senator R ...

, low wages or poor workplace conditions.

In the political and economic philosophies of Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Mikhail Bakunin, class struggle is a central tenet and a practical means for effecting radical sociopolitical changes for the social majority, the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

.

Usage

In political science,

In political science, socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

and Marxists use the term ''class conflict'' to define a social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inc ...

by its relationship to the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

, such as factories, agricultural land, and industrial machinery. The social control of labor and of the production of goods and services, is a political contest between the social classes.

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin said that the class struggles of the working class, the peasantry, and the working poor were central to realizing a social revolution to depose and replace the ruling class, and the creation of libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

.

Marx's theory of history

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

proposes that class conflict is decisive in the history of economic systems organized by hierarchies of social class such as capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

. Marxists refer to its overt manifestations as class war, a struggle whose resolution in favor of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

is viewed by them as inevitable under the plutocratic

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any establish ...

capitalism.

Oligarchs versus commoners

Where societies are socially divided based on status, wealth, or control of social production and distribution, class structures arise and are thus coeval with civilization itself. This has been well documented since at least Europeanclassical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

such as the Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the pl ...

and Spartacus, among others.

Thucydides

In his ''History'',Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

describes a civil war in the city of Corcyra between the pro-Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

party of the common people and their pro-Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

opposition. Near the climax of the struggle, "the oligarchs in full rout, fearing that the victorious commons might assault and carry the arsenal and put them to the sword, fired the houses round the market-place and the lodging-houses, in order to bar their advance."

The historian Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

would later recount a similar class conflict in the city of Seleucia, in which disharmony between the oligarchs and the commoners would typically lead to each side calling on outside help to defeat the other. Thucydides believed that "as long as poverty gives men the courage of necessity, ..so long will the impulse never be wanting to drive men into danger."

Aristotle

In his treatise ''Politics'',Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

describes the basic dimensions of class war: "Again, because the rich are generally few in number, while the poor are many, they appear to be antagonistic, and as the one or the other prevails they form the government.". Aristotle also commented that "poverty is the parent of revolution." However, he did not consider this its only cause. In a society where property is distributed equally across the community, "the nobles will be dissatisfied because they think themselves worthy of more than an equal share of honor's; and this is often found to be a cause of sedition and revolution." Aristotle thought it wrong for the poor to seize the wealth of the rich and divide it among themselves, but he also thought it wrong for the rich to impoverish the multitude.

Moreover, he discussed what he considered a middle way between laxity and cruelty in the treatment of slaves by their masters, averring that "if not kept in hand, lavesare insolent, and think that they are as good as their masters, and, if harshly treated, they hate and conspire against them."

Socrates

Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

was perhaps the first major Greek philosopher to describe class war. In Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's ''Republic'', Socrates proposes that "any city, however small, is in fact divided into two, one the city of the poor, the other of the rich; these are at war with one another." Socrates took a poor view of oligarchies, in which members of a small class of wealthy property owners take positions of power in order to dominate a large class of impoverished commoners. He used the analogy of a maritime pilot

A maritime pilot, marine pilot, harbor pilot, port pilot, ship pilot, or simply pilot, is a mariner who maneuvers ships through dangerous or congested waters, such as harbors or river mouths. Maritime pilots are regarded as skilled profession ...

, who, like a powerholder in a polis, ought to be chosen for his skill, not for the amount of property he owns.

Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

recounts how various classical figures took part in class conflict. Oppressed by their indebtedness to the rich, the mass of Athenians chose Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politic ...

to be the lawgiver to lead them to freedom from their creditors. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

believed that Solon's constitution of the Athenian popular assembly created a political sphere that had the effect of balancing the interests of the three main classes of Athens:

* The wealthy aristocratic party of the plain

* The poorer common party of the mountains

* The moderate party of the coast

Participation in Ancient Greek class war could have dangerous consequences. Plutarch noted of King Agis of Sparta that, "being desirous to raise the people, and to restore the noble and just form of government, now long fallen into disuse, eincurred the hatred of the rich and powerful, who could not endure to be deprived of the selfish enjoyment to which they were accustomed."

Patricians versus plebeians

It was similarly difficult for the Romans to maintain peace between the upper class, the patricians, and the lower class, theplebs

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins ...

. French Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

notes that this conflict intensified after the overthrow of the Roman monarchy.

In '' The Spirit of Laws'' he lists the four main grievances of the plebs, which were rectified in the years following the deposition of King Tarquin:

* The patricians had much too easy access to positions of public service.

* The constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

granted the consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

far too much power.

* The plebs were constantly verbally slighted.

* The plebs had too little power in their assemblies.

Camillus

The Senate had the ability to give a magistrate the power ofdictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

, meaning he could bypass public law in the pursuit of a prescribed mandate. Montesquieu explains that the purpose of this institution was to tilt the balance of power in favour of the patricians. However, in an attempt to resolve a conflict between the patricians and the plebs, the dictator Camillus used his power of dictatorship to coerce the Senate into giving the plebs the right to choose one of the two consuls.

Marius

Tacitus believed that the increase in Roman power spurred the patricians to expand their power over more and more cities. This process, he felt, exacerbated pre-existing class tensions with the plebs, and eventually culminated in a civil war between the patrician Sulla and the populist reformer Marius. Marius had taken the step of enlisting ''capite censi

''Capite censi'' were literally, in Latin, "those counted by head" in the ancient Roman census. Also known as "the head count", the term was used to refer to the lowest class of citizens, people not of the nobility or middle classes, owning littl ...

'', the very lowest class of citizens, into the army, for the first time allowing non-land owners into the legions.

Tiberius Gracchus

Of all the notable figures discussed by Plutarch and Tacitus, agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus may have most challenged the upper classes and most championed the cause of the lower classes. In a speech to the common soldiery, he decried their lowly conditions:

Of all the notable figures discussed by Plutarch and Tacitus, agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus may have most challenged the upper classes and most championed the cause of the lower classes. In a speech to the common soldiery, he decried their lowly conditions:

"The savage beasts," said he, "in Italy, have their particular dens, they have their places of repose and refuge; but the men who bear arms, and expose their lives for the safety of their country, enjoy in the meantime nothing more in it but the air and light; and having no houses or settlements of their own, are constrained to wander from place to place with their wives and children."Following this observation, he remarked that these men "fought indeed and were slain, but it was to maintain the luxury and the wealth of other men."

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

believed that Tiberius Gracchus's reforming efforts saved Rome from tyranny, arguing:

Tiberius Gracchus (says Cicero) caused the free-men to be admitted into theTiberius Gracchus weakened the power of the Senate by changing the law so that judges were chosen from the ranks of thetribes The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confli ..., not by the force of his eloquence, but by a word, by a gesture; which had he not effected, the republic, whose drooping head we are at present scarce able to uphold, would not even exist.

knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

, instead of their social superiors in the senatorial class.

Julius Caesar

Contrary to Shakespeare's depiction ofJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

in the tragedy ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

'', historian Michael Parenti has argued that Caesar was a populist, not a tyrant. In 2003 The New Press published Parenti's ''The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome.'' ''Publishers Weekly'' said "Parenti ..narrates a provocative history of the late republic in Rome (100–33 BC) to demonstrate that Caesar's death was the culmination of growing class conflict, economic disparity and political corruption." ''Kirkus Reviews'' wrote: "Populist historian Parenti... views ancient Rome’s most famous assassination not as a tyrannicide but as a sanguinary scene in the never-ending drama of class warfare."

Coriolanus

The patrician Coriolanus, whose life

The patrician Coriolanus, whose life William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

would later depict in the tragic play '' Coriolanus'', fought on the other side of the class war, for the patricians and against the plebs. When grain arrived to relieve a serious shortage in the city of Rome, the plebs made it known that they felt it ought to be divided amongst them as a gift, but Coriolanus stood up in the Senate against this idea on the grounds that it would empower the plebs at the expense of the patricians.

This decision would eventually contribute to Coriolanus's undoing when he was impeached following a trial by the tribunes of the plebs. Montesquieu recounts how Coriolanus castigated the tribunes for trying a patrician, when in his mind no one but a consul had that right, although a law had been passed stipulating that all appeals affecting the life of a citizen had to be brought before the plebs.

In the first scene of Shakespeare's ''Coriolanus'', a crowd of angry plebs gathers in Rome to denounce Coriolanus as the "chief enemy to the people" and "a very dog to the commonalty" while the leader of the mob speaks out against the patricians thusly:

They ne'er cared for us yet: suffer us to famish, and their store-houses crammed with grain; make edicts for usury, to support usurers; repeal daily any wholesome act established against the rich, and provide more piercing statutes daily, to chain up and restrain the poor. If the wars eat us not up, they will; and there's all the love they bear us.

Landlessness and debt

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, i ...

might have agreed with this narrative of Roman class conflict. In the third volume of ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'' is a six-volume work by the English historian Edward Gibbon. It traces Western civilization (as well as the Islamic and Mongolian conquests) from the height of the Roman Empire to th ...

'', he relates the origins of the struggle:e plebeians of Rome ..had been oppressed from the earliest times by the weight of debt and usury; and the husbandman, during the term of his military service, was obliged to abandon the cultivation of his farm. The lands of Italy which had been originally divided among the families of free and indigent proprietors, were insensibly purchased or usurped by the avarice of the nobles; and in the age which preceded the fall of the republic, it was computed that only two thousand citizens were possessed of an independent substance.

Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

similarly states that the 'severity of the patricians their creditors, the debts due to whom they had to discharge by slave-work, drove the plebs to revolts.' Gibbon also explains how Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

facilitated this class warfare by pacifying the plebs with actual bread and circuses

"Bread and circuses" (or bread and games; from Latin: ''panem et circenses'') is a metonymic phrase referring to superficial appeasement. It is attributed to Juvenal, a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE, and is used ...

.

The economist Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

noted that the poor freeman's lack of land provided a major impetus for Roman colonisation, as a way to relieve class tensions at home between the rich and the landless poor. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

described the same phenomenon happening in the impetus to Greek colonisation

Greek colonization was an organised colonial expansion by the Archaic Greeks into the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea in the period of the 8th–6th centuries BC.

This colonization differed from the migrations of the Greek Dark Ages in that ...

.

Masters versus workmen

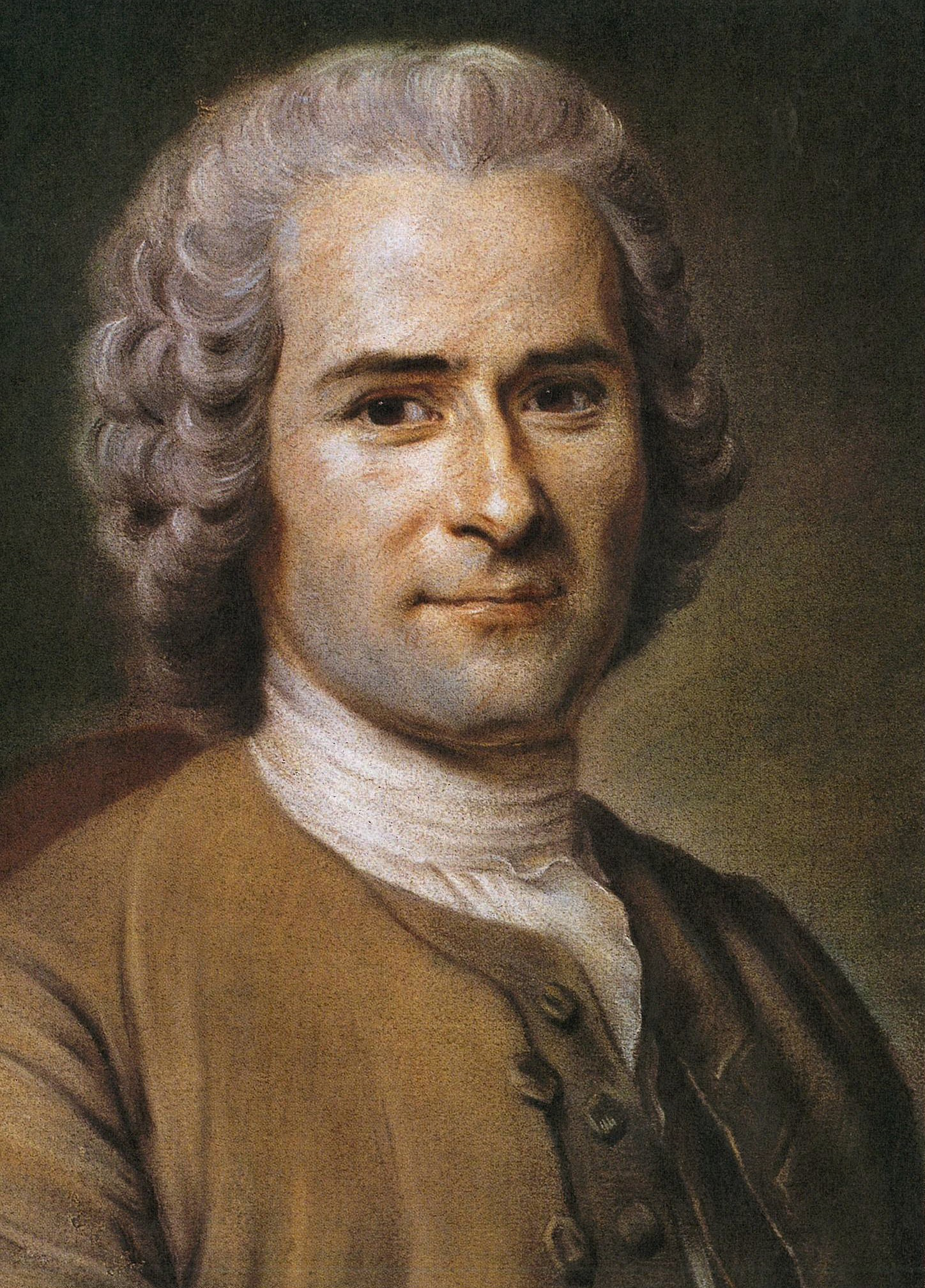

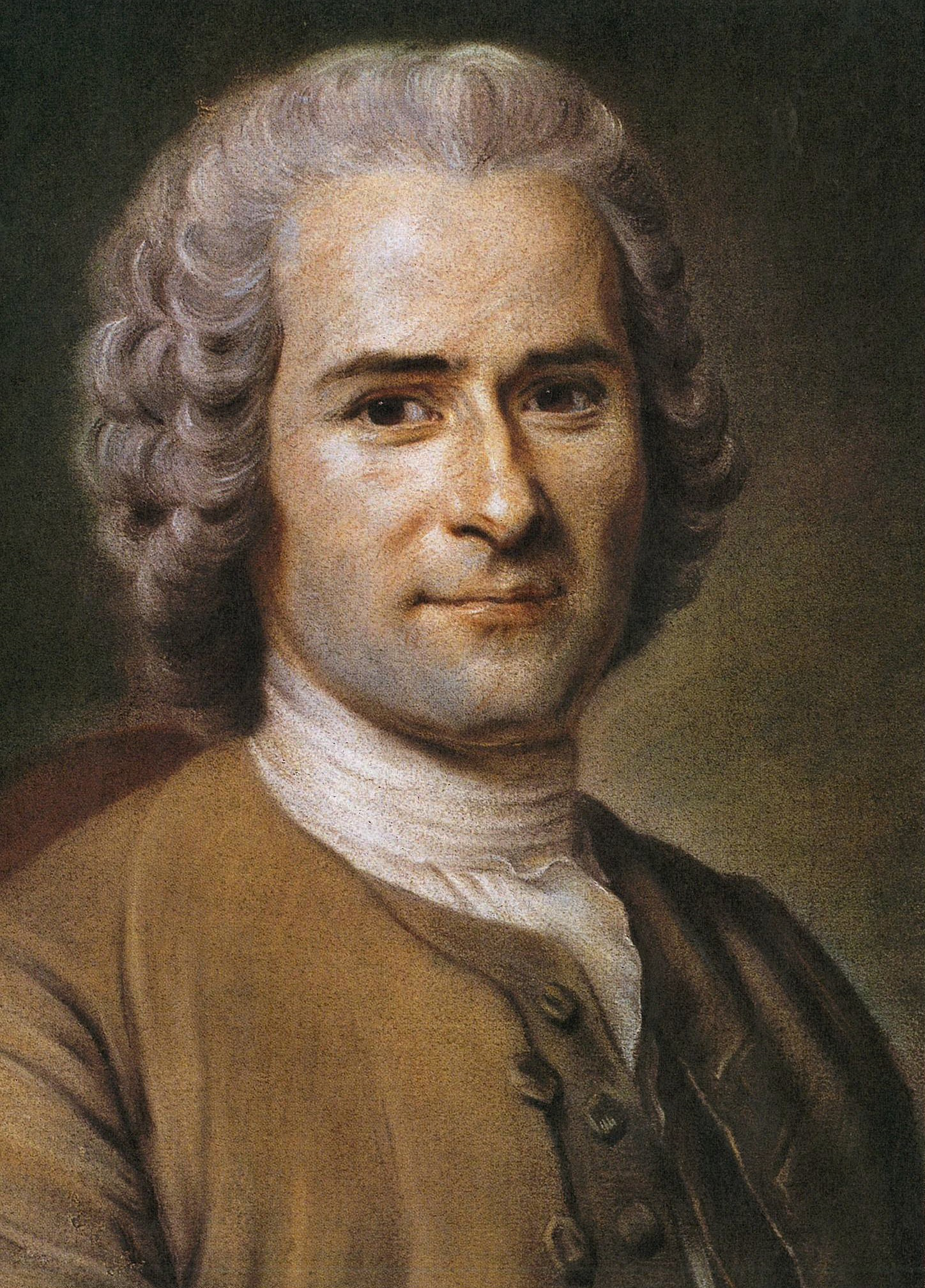

Writing in pre-capitalist Europe, both the Swiss ''philosophe''Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

and the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

philosopher Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

made significant remarks on the dynamics of class struggle, as did the Federalist statesman James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

across the Atlantic Ocean. Later, in the age of early industrial capitalism, English political economist John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and German idealist

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionar ...

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

would also contribute their perspectives to the discussion around class conflict between employers and employees.

Rousseau

It was with bitter sarcasm that Rousseau outlined the class conflict prevailing in his day between masters and their workmen:

It was with bitter sarcasm that Rousseau outlined the class conflict prevailing in his day between masters and their workmen: You have need of me, because I am rich and you are poor. We will therefore come to an agreement. I will permit you to have the honour of serving me, on condition that you bestow on me the little you have left, in return for the pains I shall take to command you.Rousseau argued that the most important task of any government is to fight in class warfare on the side of workmen against their masters, who he said engage in exploitation under the pretence of serving society. Specifically, he believed that governments should actively intervene in the economy to abolish poverty and prevent the accrual of too much wealth in the hands of too few men.

Adam Smith

Like Rousseau, the classical liberalAdam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

believed that the amassing of property in the hands of a minority naturally resulted in a disharmonious state of affairs where "the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of many" and "excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade he rich man'spossessions."

Concerning wages, he explained the conflicting class interests of masters and workmen, who he said were often compelled to form trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

for fear of suffering starvation wages, as follows:What are the common wages of labour, depends everywhere upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little, as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower, the wages of labour.Smith was aware of the main advantage of masters over workmen, in addition to state protection:Adam Smith Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations''

Book I, Chapter 8.Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks." It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital libr ....

The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily: and the law, besides, authorises, or at least does not prohibit, their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work, but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes, the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, or merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks, which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year, without employment. In the long run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.Smith observed that, outside of colonies where land is cheap and labour expensive, both the masters who subsist by profit and the masters who subsist by rents will work in tandem to subjugate the class of workmen, who subsist by wages. Moreover, he warned against blindly legislating in favour of the class of masters who subsist by profit, since, as he said, their intention is to gain as large a share of their respective markets as possible, which naturally results in monopoly prices or close to them, a situation harmful to the other social classes.

James Madison

In his Federalist No. 10,James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

revealed an emphatic concern with the conflict between rich and poor, commenting that "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination." He welcomed class-based factions into political life as a necessary result of political liberty, stating that the most important task of government was to manage and adjust for 'the spirit of party'.

John Stuart Mill

Adam Smith was not the only classical liberal political economist concerned with class conflict. In his ''Considerations on Representative Government

''Considerations on Representative Government'' is a book by John Stuart Mill published in 1861.

Summary

Mill argues for representative government, the ideal form of government in his opinion. One of the more notable ideas Mill puts forth in the ...

'', John Stuart Mill observed the complete marginalisation of workmen's voices in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, rhetorically asking whether its members ever empathise with the position of workmen, instead of siding entirely with their masters, on issues such as the right to go on strike. Later in the book, he argues that an important function of truly representative government is to provide a relatively equal balance of power between workmen and masters, in order to prevent threats to the good of the whole of society.

During Mill's discussion of the merits of progressive taxation

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases.Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), ''Concepts of Taxation'', Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX The term ''progr ...

in his essay ''Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

'', he notes as an aside the power of the rich as independent of state support:People feel obliged to argue that the State does more for the rich than for the poor, as a justification for its taking more n taxationfrom them: though this is in reality not true, for the rich would be far better able to protect themselves, in the absence of law or government, than the poor, and indeed would probably be successful in converting the poor into their slaves.

Hegel

In his '' Philosophy of Right'',Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

expressed concern that the standard of living of the poor might drop so far as to make it even easier for the rich to amass even more wealth. Hegel believed that, especially in a liberal country such as contemporary England, the poorest will politicise their situation, channelling their frustrations against the rich:Against nature man can claim no right, but once society is established, poverty immediately takes the form of a wrong done to one class by another.

Capitalist societies

The typical example of class conflict described is class conflict within capitalism. This class conflict is seen to occur primarily between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and takes the form of conflict over hours of work, value of wages, division of profits, cost of consumer goods, the culture at work, control overparliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

or bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

, and economic inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of ...

. The particular implementation of government programs which may seem purely humanitarian, such as disaster relief, can actually be a form of class conflict.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

(1743–1826) led the U.S. as president from 1801 to 1809 and is considered one of the founding fathers. Regarding the interaction between social classes, he wrote:

Max Weber

Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas p ...

(1864–1920) agreed with the fundamental ideas of Karl Marx about the economy causing class conflict, but claimed that class conflict can also stem from prestige and power. Weber argued that classes come from the different property locations. Different locations can largely affect one's class by their education and the people they associate with. He also stated that prestige results in different status groupings. This prestige is based upon the social status of one's parents. Prestige is an attributed value and many times cannot be changed. Weber stated that power differences led to the formation of political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

. Weber disagreed with Marx about the formation of classes. While Marx believed that groups are similar due to their economic status, Weber argued that classes are largely formed by social status

Social status is the level of social value a person is considered to possess. More specifically, it refers to the relative level of respect, honour, assumed competence, and deference accorded to people, groups, and organizations in a society. St ...

. Weber did not believe that communities are formed by economic standing, but by similar social prestige. Weber did recognize that there is a relationship between social status, social prestige and classes.

Twentieth century

In the U.S., class conflict is often noted in labor/management disputes. As far back as 1933 representative Edward Hamilton of the Airline Pilot's Association, used the term "class warfare" to describe airline management's opposition at the National Labor Board hearings in October of that year. Apart from these day-to-day forms of class conflict, during periods of crisis or revolution class conflict takes on a violent nature and involves repression, assault, restriction of civil liberties, and murderous violence such as assassinations or death squads.Twenty-first century

Financial crisis

Class conflict intensified in the period after the 2007/8 financial crisis, which led to a global wave ofanti-austerity protests

The anti-austerity movement refers to the mobilisation of street protests and grassroots campaigns that has happened across various countries, especially in Europe, since the onset of the worldwide Great Recession.

Anti-austerity actions are var ...

, including the Greek and Spanish Indignados movements and later the Occupy movement

The Occupy movement was an international populist socio-political movement that expressed opposition to social and economic inequality and to the perceived lack of "real democracy" around the world. It aimed primarily to advance social and econo ...

, whose slogan was " We are the 99%", signalling a more expansive class antagonist against the financial elite than that of the classical Marxist proletariat.

The investor, billionaire

A billionaire is a person with a net worth of at least one billion (1,000,000,000, i.e., a thousand million) units of a given currency, usually of a major currency such as the United States dollar, euro, or pound sterling. The American busi ...

, and philanthropist Warren Buffett

Warren Edward Buffett ( ; born August 30, 1930) is an American business magnate, investor, and philanthropist. He is currently the chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway. He is one of the most successful investors in the world and has a net ...

, one of the wealthiest people in the world, voiced in 2005 and once more in 2006 his view that his class, the "rich class", is waging class warfare on the rest of society. In 2005 Buffet said to CNN: "It's class warfare, my class is winning, but they shouldn't be." In a November 2006 interview in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Buffett stated that " ere’s class warfare all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning."

In the speech "The Great American Class War" (2013), the journalist Bill Moyers asserted the existence of social-class conflict between democracy and plutocracy in the U.S. Chris Hedges

Christopher Lynn Hedges (born September 18, 1956) is an American journalist, Presbyterian minister, author, and commentator.

In his early career, Hedges worked as a freelance war correspondent in Central America for '' The Christian Science M ...

wrote a column for '' Truthdig'' called "Let's Get This Class War Started", which was a play on Pink's song " Let's Get This Party Started." In a 2022 piece "America’s New Class War", Hedges argues that increased class struggle and strikes by organized workers, often in defiance of union leadership, is the "one last hope for the United States."

Historian Steve Fraser, author of ''The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power'', asserted in 2014 that class conflict is an inevitability if current political and economic conditions continue, noting that "people are increasingly fed up ..their voices are not being heard. And I think that can only go on for so long without there being more and more outbreaks of what used to be called class struggle, class warfare."

Arab Spring

Often seen as part of the same "movement of squares" as the Indignado and Occupy movements, theArab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econo ...

was a wave of social protests starting in 2011. Numerous factors have culminated in the Arab Spring, including rejection of dictatorship or absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

, human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

violations, government corruption (demonstrated by Wikileaks diplomatic cables), economic decline, unemployment, extreme poverty, and a number of demographic structural factors, such as a large percentage of educated but dissatisfied youth within the population. but class conflict is also a key factor. The catalysts for the revolts in all Northern African and Persian Gulf countries

The Arab states of the Persian Gulf refers to a group of Arab states which border the Persian Gulf. There are seven member states of the Arab League in the region: Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. ...

have been the concentration of wealth in the hands of autocrats in power for decades, insufficient transparency of its redistribution, corruption, and especially the refusal of the youth to accept the status quo.

Socialism

Marxist perspectives

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

(1818–1883) was a German born philosopher who lived the majority of his adult life in London, England. In '' The Communist Manifesto'', Karl Marx argued that a class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

is formed when its members achieve class consciousness and solidarity.Blackwell Reference Online.'. Retrieved 24 November 2008. This largely happens when the members of a class become aware of their Exploitation of labour, exploitation and the conflict with another class. A class will then realize their shared interests and a common identity. According to Marx, a class will then take action against those that are exploiting the lower classes. What Marx points out is that members of each of the two main classes have interests in common. These class or collective interests are in conflict with those of the other class as a whole. This in turn leads to conflict between individual members of different classes. Marxist analysis of society identifies two main social groups: * ''Labour'' (the proletariat or workers) includes anyone who earns their livelihood by selling their labor power and being paid a wage or salary for their labor time. They have little choice but to work for capital, since they typically have no independent way to survive. * ''Capital'' (the bourgeoisie or capitalists) includes anyone who gets their income not from labor as much as from the

surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to the owner of that product to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cos ...

they appropriate from the workers who create wealth. The income of the capitalists, therefore, is based on their exploitation of the workers (proletariat).

Not all class struggle is violent or necessarily radical, as with strikes and lockouts. Class antagonism may instead be expressed as low worker morale, minor sabotage and pilferage, and individual workers' abuse of petty authority and hoarding of information. It may also be expressed on a larger scale by support for socialist or populist parties. On the employers' side, the use of union busting legal firms and the lobbying for anti-union laws are forms of class struggle.

Not all class struggle is a threat to capitalism, or even to the authority of an individual capitalist. A narrow struggle for higher wages by a small sector of the working-class, what is often called "economism", hardly threatens the status quo. In fact, by applying the craft-union tactics of excluding other workers from skilled trades, an economistic struggle may even weaken the working class as a whole by dividing it. Class struggle becomes more important in the historical process as it becomes more general, as industries are organized rather than crafts, as workers' class consciousness rises, and as they self-organize away from political parties. Marx referred to this as the progress of the proletariat from being a class "in itself", a position in the social structure, to being one "for itself", an active and conscious force that could change the world.

Marx largely focuses on the capital industrialist society as the source of social stratification

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and politi ...

, which ultimately results in class conflict. He states that capitalism creates a division between classes which can largely be seen in manufacturing factories. The proletariat, is separated from the bourgeoisie because production becomes a social enterprise. Contributing to their separation is the technology that is in factories. Technology de-skills and alienates workers as they are no longer viewed as having a specialized skill. Another effect of technology is a homogenous workforce

The workforce or labour force is a concept referring to the pool of human beings either in employment or in unemployment. It is generally used to describe those working for a single company or industry, but can also apply to a geographic reg ...

that can be easily replaceable. Marx believed that this class conflict would result in the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and that the private property would be communally owned. The mode of production would remain, but communal ownership would eliminate class conflict.

Even after a revolution, the two classes would struggle, but eventually the struggle would recede and the classes dissolve. As class boundaries broke down, the state apparatus would wither away. According to Marx, the main task of any state apparatus is to uphold the power of the ruling class; but without any classes there would be no need for a state. That would lead to the classless

The term classless society refers to a society in which no one is born into a social class. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievemen ...

, stateless communist society.

Soviet Union and similar societies

A variety of thinkers, mostly Trotskyist andanarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

, argue that class conflict existed in Soviet-style societies. Their arguments describe as a class the bureaucratic stratum

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

formed by the ruling political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

(known as the '' nomenklatura'' in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

), sometimes termed a " new class", that controls and guides the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

. This ruling class is viewed to be in opposition to the remainder of society, generally considered the proletariat. This type of system is referred by them as state socialism, state capitalism, bureaucratic collectivism or new class societies. Marxism was already a powerful ideological power in Russia before the Soviet Union was created in 1917, since a Marxist group known as the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

existed. This party soon divided into two main factions; the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, who were led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, and the Mensheviks, who were led by Julius Martov.

However, many Marxists argue that unlike in capitalism, the Soviet elites did not own the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

, or generated surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to the owner of that product to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cos ...

for their personal wealth like in capitalism as the generated profit from the economy was equally distributed into Soviet society. Even some Trotskyist like Ernest Mandel criticized the concept of a new ruling class as an oxymoron, saying: "The hypothesis of the bureaucracy’s being a new ruling class leads to the conclusion that, for the first time in history, we are confronted with a 'ruling class' which does not exist as a class before it actually rules."

Non-Marxist perspectives

One of the first writers to comment on class struggle in the modern sense of the term was theFrench revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

ary François Boissel. Other class struggle commentators include Henri de Saint-Simon, Augustin Thierry

Augustin Thierry (or ''Jacques Nicolas Augustin Thierry''; 10 May 179522 May 1856) was a French historian. Although originally a follower of Henri de Saint-Simon, he later developed his own approach to history. A committed liberal, his approach ...

, François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the ...

, François-Auguste Mignet and Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

. The Physiocrat

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists who believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricult ...

s, David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist. He was one of the most influential of the classical economists along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill. Ricardo was also a politician, and a ...

, and after Marx, Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

noted the inelastic supply of land and argued that this created certain privileges (economic rent

In economics, economic rent is any payment (in the context of a market transaction) to the owner of a factor of production in excess of the cost needed to bring that factor into production. In classical economics, economic rent is any payment ...

) for landowners. According to the historian Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Colleg ...

, stratification along lines of class appears only within civilizations, and furthermore only appears during the process of a civilization's decline while not characterizing the growth phase of a civilization.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

, in '' What is Property?'' (1840) states that "certain classes do not relish investigation into the pretended titles to property, and its fabulous and perhaps scandalous history." While Proudhon saw the solution as the lower classes forming an alternative, solidarity economy centered on cooperatives and self-managed workplaces, which would slowly undermine and replace capitalist class society, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, while influenced by Proudhon, insisted that a massive class struggle by the working class, peasantry and poor was essential to the creation of libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

. This would require a final showdown in the form of a social revolution.

One of the earliest analyses of the development of class as the development of conflicts between emergent classes is available in Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activist ...

's '' Mutual Aid''. In this work, Kropotkin analyzes the disposal of goods after death in pre-class or hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

societies, and how inheritance produces early class divisions and conflict.

Fascists

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

have often opposed 'horizontal' class struggle in favour of vertical national struggle and instead have attempted to appeal to the working class while promising to preserve the existing social classes and have proposed an alternative concept known as class collaboration.

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky i ...

, American linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Lingu ...

, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, and political activist, has criticized class war in the United States:

Libertarianism

Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer argued that class struggle came from factions that managed to gain control of the State power. Theruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by ex ...

are the groups that seize the power of the State to carry out their political agenda, the ''ruled'' are then taxed and regulated by the State for the benefit of the Ruling classes. Through taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

, state power, subsidies, Tax codes, laws, and privileges the State creates class conflict by giving preferential treatment to some at the expense of others by force. In the free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

, by contrast, exchanges are not carried out by force but by the Non-aggression principle of cooperation in a Win-win scenario.

Relationship to race

Some historical tendencies of Orthodox Marxism rejectracism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

, sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers pri ...

, etc. as struggles that essentially distract from class struggle, the real conflict. These divisions within the class prevent the purported antagonists from acting in their common class interest. However, many Marxist internationalists and anti-colonial revolutionaries believe thasex, race and class

are bound up together. Within Marxist scholarship there is an ongoing debate about these topics. According to

Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and ho ...

, in the 19th century, the essentialist

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Plato's idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In ''Categories'', Aristotle si ...

notion of the " race" was incorporated by racists, biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize ...

s, and eugenicists, who gave it the modern sense of "biological race" which was then integrated into " state racism". On the other hand, Foucault claims that when Marxists developed their concept of "class struggle", they were partly inspired by the older, non-biological notions of the "race" and the "race struggle". Quoting a non-existent 1882 letter from Marx to Friedrich Engels during a lecture, Foucault erroneously claimed Marx wrote: "You know very well where we found our idea of class struggle; we found it in the work of the French historians who talked about the race struggle." For Foucault, the theme of social war provides the overriding principle that connects class and race struggle.

Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor ...

, an important theoretician and labor Zionist of the early socialist movement, in his "Epilogue" to "Rome and Jerusalem

''Rome and Jerusalem: The Last National Question'' (german: Rom und Jerusalem, die Letzte Nationalitätsfrage) is a book published by Moses Hess in 1862 in Leipzig. It gave impetus to the Labor Zionism movement. In his ''magnum opus'', Hess argued ...

" argued that "the race struggle is primary, the class struggle secondary. ..With the cessation of race antagonism, the class struggle will also come to a standstill. The equalization of all classes of society will necessarily follow the emancipation of all the races, for it will ultimately become a scientific question of social economics."

W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up i ...

theorized that the intersectional

Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how aspects of a person's social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality identifies multiple factors of adva ...

paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain certain aspects of black political economy. Patricia Hill Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."

In modern times, emerging schools of thought in the U.S. and other countries hold the opposite to be true. They argue that the race struggle is less important, because the primary struggle is that of class since labor of all races face the same problems and injustices.

Chronology

Riots with a nationalist background are not included.Classical antiquity

* Gracchi Tribuneship * Social War, 91–88 BC *Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland). Gallic, Germanic, and British tribes fought to defend their homel ...

and the assassination of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, according to Michael Parenti

* Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the pl ...

* Roman Servile Wars

* Yellow Turban Rebellion

The Yellow Turban Rebellion, alternatively translated as the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, was a peasant revolt in China against the Eastern Han dynasty. The uprising broke out in 184 CE during the reign of Emperor Ling. Although the main rebelli ...

, 184–205 AD

Middle Ages

* Ciompi in Florence, 1378 *Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

in England, 1381

* Jacquerie in 14th-century France

* Saint George's Night Uprising

Modern era

* German Peasants' War since 1524

*

* German Peasants' War since 1524

* Shimabara Rebellion

The , also known as the or , was an uprising that occurred in the Shimabara Domain of the Tokugawa Shogunate in Japan from 17 December 1637 to 15 April 1638.

Matsukura Katsuie, the '' daimyō'' of the Shimabara Domain, enforced unpopular p ...

, 1637–1638

* English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, 1642–1651 ( Diggers)

* French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

since 1789see Daniel Guérin, Class Struggle in the First French Republic, Pluto Press 1977

* Old Price Riots

The Old Price Riots of 1809 (also sometimes referred to as the O.P. or OP riots) were caused by rising prices at the new Theatre at Covent Garden, London, after the previous one had been destroyed by fire. Covent Garden was one of two "patent" t ...

, 1809

* July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first in 1789. It led to ...

, 1830

* Canut revolts in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

since 1831, often considered as the beginning of the modern labor movement

* June Rebellion, 1832

* Galician slaughter

The Galician Slaughter, also known as the Galician Rabacja, Peasant Uprising of 1846 or the Szela uprising (german: Galizischer Bauernaufstand; pl, Rzeź galicyjska or ''Rabacja galicyjska''), was a two-month uprising of impoverished Galicia ...

, 1846

* Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

in France et al.

* Newport Rising, political revolt in 1839 led by Chartists

* Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

, 1871

* Johnson County War, 1889–1893

* Coal Wars, 1890–1930

* Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution (), also known as the Donghak Peasant Movement (), Donghak Rebellion, Peasant Revolt of 1894, Gabo Peasant Revolution, and a variety of other names, was an armed rebellion in Korea led by peasants and followers of ...

in Korea, 1893/1894

* 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

* 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt

* Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, 1910-1920

* October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in 1917

* Limerick Soviet in Ireland, 1919

* Spartacist uprising in Germany, 1919

* Seattle General Strike of 1919 in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

* General Strike of 1919 in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

* Winnipeg General Strike, 1919

* Ruhr Uprising in Germany, 1920

* Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Loc ...

, 1921

* Battle of Blair Mountain, 1921

* Hamburg Uprising