Clarence King on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Clarence Rivers King (January 6, 1842 – December 24, 1901) was an American

At Yale, King specialized in "applied chemistry" and also studied physics and geology. One inspiring teacher was

At Yale, King specialized in "applied chemistry" and also studied physics and geology. One inspiring teacher was

King made a persuasive argument for how his research would help develop the West. He received federal funding and was named U.S. Geologist of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, commonly known as the Fortieth Parallel Survey, in 1867. He persuaded Gardiner to be his second in command and they assembled a team that included, among others, Samuel Franklin Emmons,

King made a persuasive argument for how his research would help develop the West. He received federal funding and was named U.S. Geologist of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, commonly known as the Fortieth Parallel Survey, in 1867. He persuaded Gardiner to be his second in command and they assembled a team that included, among others, Samuel Franklin Emmons,

Emmons, Samuel Franklin (1903). ''Biographical Memoir of Clarence King''

* Hague, James D., ed. (1904). ''Clarence King Memoirs. The Helmet of Mambrino''. New York: Published for the King Memorial Committee of the Century Association by G.P. Putnam's Son

* Original drawings by L.F. Bjorklund. Extensive bibliography. * * * King, one of four Americans on whom the author focuses, was influenced by

Address of Clarence King on Catastrophism

and " Catastrophism in Geology",

USGS: The Four Great Surveys of the West

''Clarence King (1842–1901): Pioneering Geologist of the West'', Geological Society of America

''Biographical memoir of Clarence King, 1842–1901''

by Samuel Franklin Emmons.

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:King, Clarence American geologists American mountain climbers American art critics Explorers of the United States United States Geological Survey personnel 1842 births 1901 deaths History of the Sierra Nevada (United States) Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni Impostors Tuberculosis deaths in Arizona 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis Burials in Rhode Island Writers from Newport, Rhode Island

geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

, mountaineer

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, an ...

and author. He was the first director of the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

from 1879 to 1881. Nominated by Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

, King was noted for his exploration of the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Early life and education

Clarence King was the son of James Rivers King and Florence Little King. Clarence's father was part of a family firm engaged in trade with China, which kept him away from home a great deal, and he died in 1848, so Clarence was brought up primarily by his mother. By 1848, his only two siblings had also died. Clarence developed an early interest in outdoor exploration and natural history, which was encouraged by his mother and by Reverend Dr. Roswell Park, head of the Christ Church Hall school inPomfret, Connecticut

Pomfret is a town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 4,266 in 2020 according to the 2020 United States Census. The land was purchased from Native Americans in 1686 (the "Mashmuket Purchase" or "Mashamoquet Purchase ...

, that Clarence attended until he was ten. He then attended schools in Boston and New Haven and, at age thirteen, was accepted to the prestigious Hartford High School

Hartford Church of England High School is a voluntary aided Church of England secondary school on Neot Road in Hartford, Cheshire, for students aged between eleven and sixteen. The school has dual specialist college status in both languages an ...

. He was a good student and a versatile athlete, of short stature but unusually strong.

His mother received an income from the King family business until it met with a series of problems and dissolved in 1857. After a few years of straitened circumstances, during part of which Clarence suffered from a serious depression, his mother married George S. Howland in July 1860. Howland financed Clarence's enrollment in the Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffiel ...

affiliated with Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

in 1860.

College life and early career

At Yale, King specialized in "applied chemistry" and also studied physics and geology. One inspiring teacher was

At Yale, King specialized in "applied chemistry" and also studied physics and geology. One inspiring teacher was James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of continent ...

, a highly regarded geologist who had participated in a scientific expedition to the South Atlantic, South Pacific and the west coasts of South and North America. King graduated with a Ph.B. in July 1862. He and several friends borrowed one of Yale's rowboats that summer for a trip along the shores of Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; french: Lac Champlain) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the US states of New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canada, Canadian province of Quebec.

The New York portion of t ...

and a series of Canadian rivers, then returned to New Haven for the fall regatta.

In October 1862, on a visit to the home of his former professor, George Jarvis Brush

George Jarvis Brush (December 15, 1831 – February 5, 1912) was an American mineralogist and academic administrator who spent most of his career at Yale University in the Sheffield Scientific School.

Career

Brush was born in Brooklyn, New York o ...

, King heard Brush read aloud a letter he had received from William Henry Brewer

William Henry Brewer (September 14, 1828 – November 2, 1910) was an American botanist. He worked on the first California Geological Survey and was the first Chair of Agriculture at Yale University's Sheffield Scientific School.

Biography

Will ...

telling of an ascent of Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta ( Shasta: ''Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki''; Karuk: ''Úytaahkoo'') is a potentially active volcano at the southern end of the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California. At an elevation of , it is the second-highest peak in the Cascades ...

in California, then believed to be the tallest mountain in the United States. King began to read more about geology, attended a lecture by Louis Agassiz, and soon wrote to Brush that he had "pretty much made up my mind to be a geologist if I can get work in that direction". He was also fascinated by descriptions of the Alps by John Tyndall and John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

.

In late 1862 or early 1863, King moved to New York City to share an apartment with James Terry Gardiner

James Terry Gardiner (May 6, 1842 – September 10, 1912) was an American surveyor and engineer.

Biography

Gardiner was born in Troy, New York, the son of Daniel Gardiner and Ann Terry Gardiner. He briefly attended Rensselaer Polytechnic In ...

, a close friend from high school and college (who spelled his last name Gardner at the time). They associated with a group of American artists, writers and architects who were admirers of Ruskin. In February 1863, King became one of the founders, along with John William Hill, Clarence Cook

Clarence Chatham Cook (September 8, 1828 – June 2, 1900) was a 19th-century American author and art critic.

Born in Dorchester, Massachusetts, Cook graduated from Harvard in 1849 and worked as a teacher. Between 1863 and 1869, Cook wrote a serie ...

and others, of the Ruskinian Association for the Advancement of Truth in Art

The American Pre-Raphaelites was a movement of landscape painters in the United States during the mid-19th century. It was named for its connection to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and for the influence of John Ruskin on its members. Painter T ...

, an American group similar to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and was elected its first secretary. But he was anxious to see the mountains of the American West, and his friend Gardiner was miserable in law school.

By May 1863, King, Gardiner and an acquaintance named William Hyde traveled by railroad to Missouri and then joined a wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings ...

, which they left at Carson City, Nevada. King and Gardiner soon continued on to California, where King joined the California Geological Survey without pay, in which he worked with William H. Brewer, Josiah D. Whitney and later Gardiner and Richard D. Cotter. In July 1864, King and Cotter made the first ascent of a peak in the Eastern Sierra that King named Mount Tyndall in honor of one of his heroes. From there they discovered several higher peaks, including the one that came to be named Mount Whitney.

In September 1864, upon the designation by President Abraham Lincoln of the Yosemite Valley

Yosemite Valley ( ; ''Yosemite'', Miwok for "killer") is a glacial valley in Yosemite National Park in the western Sierra Nevada mountains of Central California. The valley is about long and deep, surrounded by high granite summits such as Hal ...

area as a permanent public reserve, King and Gardiner were appointed to make a boundary survey around the rim of Yosemite Valley. They returned to the East Coast by way of Nicaragua the following winter. King suffered from several bouts of malaria in spring and summer 1865 while Whitney, also in the East, worked on securing funding for further survey projects. King, Gardiner, Whitney and Whitney's wife sailed back to San Francisco in the fall, where Whitney lined up a survey project for King and Gardiner in the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily ...

and Arizona under U.S. Army auspices. They returned to San Francisco in the spring, and King returned to Yosemite in summer 1866 to make more field notes for Whitney. When King heard of the death of his stepfather, he and Gardiner resigned from the Whitney survey and once again sailed to New York. They had been developing a plan for an independent survey of the Great Basin region for some time and, in late 1866, King went to Washington to secure funding from Congress for such a survey. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1871.

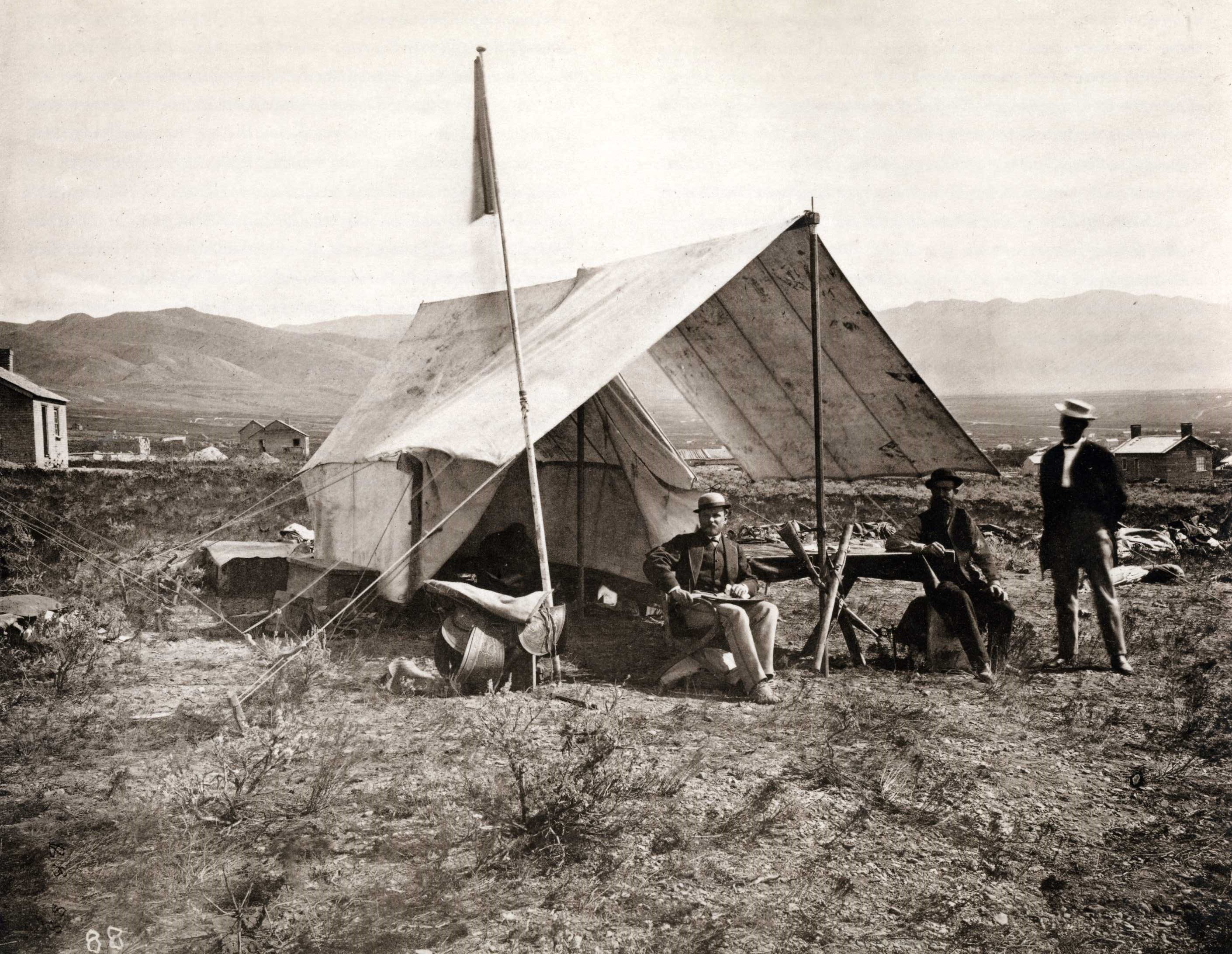

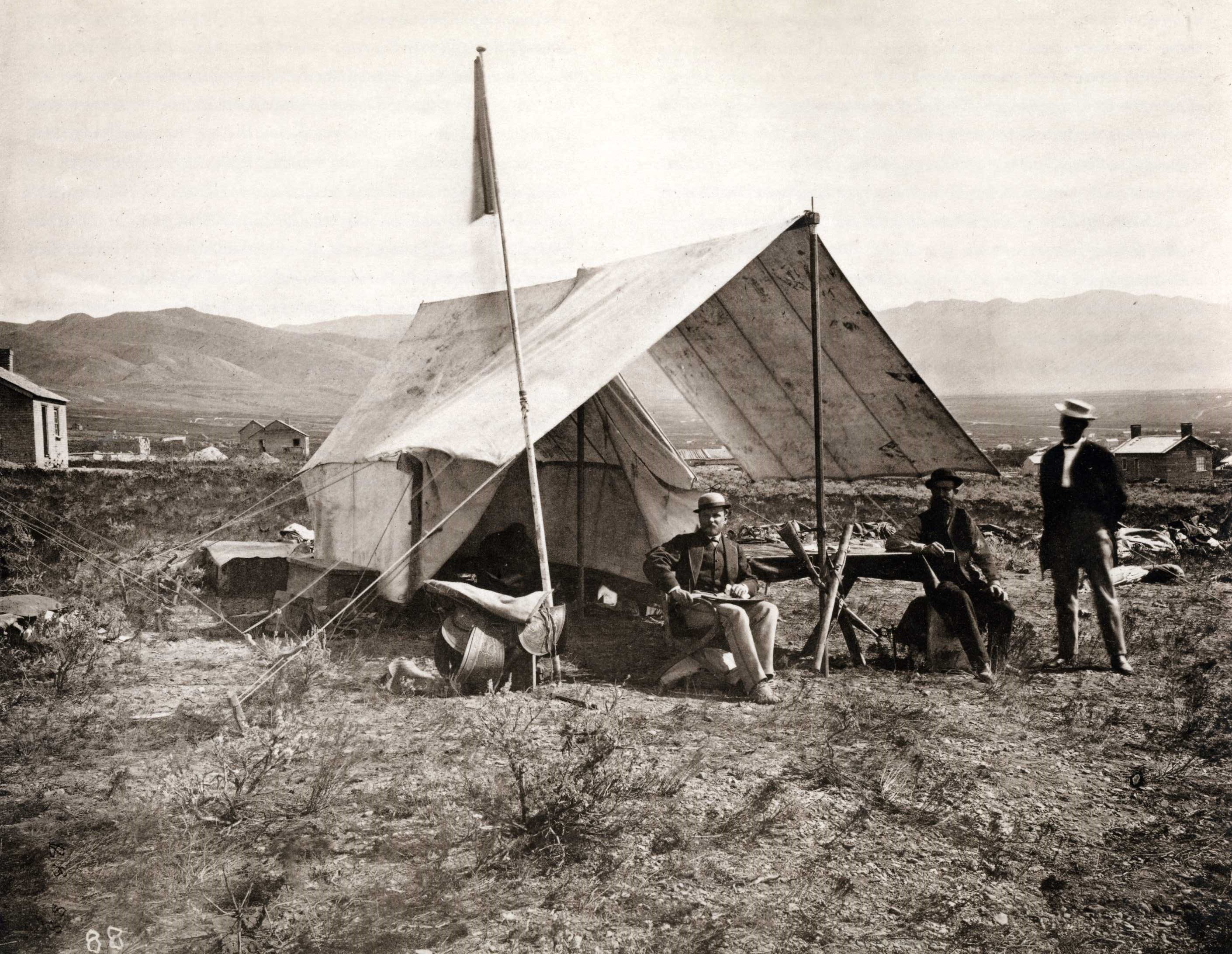

Fortieth Parallel Survey and diamond hoax discovery

King made a persuasive argument for how his research would help develop the West. He received federal funding and was named U.S. Geologist of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, commonly known as the Fortieth Parallel Survey, in 1867. He persuaded Gardiner to be his second in command and they assembled a team that included, among others, Samuel Franklin Emmons,

King made a persuasive argument for how his research would help develop the West. He received federal funding and was named U.S. Geologist of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, commonly known as the Fortieth Parallel Survey, in 1867. He persuaded Gardiner to be his second in command and they assembled a team that included, among others, Samuel Franklin Emmons, Arnold Hague

Arnold Hague (December 3, 1840 in Boston, Massachusetts – May 14, 1917 in Washington, D.C.) was a United States geologist who did many geological surveys in the U.S., of which the best known was that for Yellowstone National Park. He also had as ...

, A. D. Wilson, the photographer Timothy H. O'Sullivan and guest artist Gilbert Munger.

Over the next six years, King and his team explored areas from eastern California to Wyoming. During that time he also published his famous ''Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada'' (1872).

While King was finishing the 40th Parallel Survey, the western US was abuzz with news of a secret diamond deposit. King and some of his crew tracked down the secret location in northwest Colorado and exposed it as a fraud, now known as the Diamond hoax of 1872

The diamond hoax of 1872 was a swindle in which a pair of prospectors sold a false American diamond deposit to prominent businessmen in San Francisco and New York City. It also triggered a brief diamond prospecting craze in the western United Stat ...

. He became an international celebrity through exposing the hoax.

In 1878, King published ''Systematic Geology'', numbered Volume 1 of the Report of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, although it appeared later than all but one of the other seven volumes. In this work he narrated the geological history of the West as a mixture of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

and catastrophism. This book was well received at the time and has been called "one of the great scientific works of the late nineteenth century".

In 1879, the US Congress consolidated the number of geological surveys exploring the American West and created the United States Geological Survey. King was chosen as its first director. He took the position with the understanding that it would be temporary and he resigned after twenty months, having overseen the organization of the new agency with an emphasis on mining geology. James Garfield named John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He ...

as his successor.

During the remaining years of his life, King withdrew from the scientific community and attempted to profit from his knowledge of mining geology, but the mining ventures he was involved in were not successful enough to support his expensive tastes in art collecting, travel and elegant living, and he went heavily into debt. He had a busy social life, with close friendships including Henry Brooks Adams and John Hay, who admired him tremendously. But he suffered from physical ailments and depression.

Common law marriage and passing as African-American

King spent his last thirteen years leading a double life. In 1887 or 1888, he met and fell in love with Ada Copeland, an African-American nursemaid and former slave fromGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, who had moved to New York City in the mid-1880s. As miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

was strongly discouraged in the nineteenth century (and illegal in many places), King hid his identity from Copeland. Despite his blue eyes and fair complexion, King convinced Copeland that he was an African-American Pullman porter

Pullman porters were men hired to work for the railroads as porters on sleeping cars. Starting shortly after the American Civil War, George Pullman sought out former slaves to work on his sleeper cars. Their job was to carry passengers’ bag ...

named James Todd. The two entered into a common law marriage

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, or marriage by habit and repute, is a legal framework where a couple may be considered married without having formally registered their relation as a civil ...

in 1888. Throughout the marriage, King never revealed his true identity to Ada, pretending to be Todd, a black railroad worker, when at home, and continuing to work as King, a white geologist, when in the field. Their union produced five children, four of whom survived to adulthood. Their two daughters married white men; their two sons served classified as black during World War I. King finally revealed his true identity to Copeland in a letter he wrote to her while on his deathbed in Arizona.

Death and legacy

King died oftuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

in Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ; nv, Hoozdo; es, Fénix or , yuf-x-wal, Banyà:nyuwá) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona, with 1,608,139 residents as of 2020. It is the fifth-most populous city in the United States, and the on ...

, and was buried in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

. Kings Peak in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, Mount Clarence King

Mount Clarence King, located in the Kings Canyon National Park, is named for Clarence King, who worked on the Whitney Survey, the first geological survey of California. King later became the first chief of the United States Geological Survey.

The ...

and Clarence King Lake at Shastina

Shastina is a satellite cone of Mount Shasta. It is the highest of four overlapping volcanic cones which together form the most voluminous stratovolcano in the Cascade Range. At , Shastina is taller than Mount Adams and would rank as the thir ...

, California, are named in his honor, as is King Peak in Antarctica.

The US Geological Survey Headquarters Library in Reston, Virginia, is also known as the Clarence King Library.

Bibliography

Works about King

Emmons, Samuel Franklin (1903). ''Biographical Memoir of Clarence King''

* Hague, James D., ed. (1904). ''Clarence King Memoirs. The Helmet of Mambrino''. New York: Published for the King Memorial Committee of the Century Association by G.P. Putnam's Son

* Original drawings by L.F. Bjorklund. Extensive bibliography. * * * King, one of four Americans on whom the author focuses, was influenced by

Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

.

*

*Moore, James Gregory (2006), King of the 40th Parallel, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-5223-0

*

Works by King

* ''The Three Lakes: Marian, Lall, Jan and How They Were Named.'' 1870. * ''Report of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel.'' United States Government Printing Office, 1870–1878. * "On the Discovery of Actual Glaciers in the Mountains of the Pacific Slope," ''American Journal of Science and Arts'', vol. I, March 1871. * "Active Glaciers Within the United States," ''The Atlantic Monthly'', vol. 27, no. 161, March 1871. * ''Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada.'' Boston : James R. Osgood and Company, 1872 (much of it previously published as articles in the Atlantic Monthly) * "John Hay," ''Scribner's Monthly'', v. 7, no. 6, Apr. 1874. * "Catastrophism andEvolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

," ''The American Naturalist,'' vol. 11, no. 8, August 1877.

Address of Clarence King on Catastrophism

and " Catastrophism in Geology",

Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

articles, 14 July 1877, pp. 16–17

* ''Statistics of the Production of the Precious Metals in the United States''. United States Government Printing Office, 1881.

* ''The United States Mining Laws and Regulations Thereunder...''. United States Government Printing Office, 1885.

* "The Helmet of Mambrino," ''The Century Magazine'', Volume 32, no. 1, May 1886.

* "The Age of the Earth," ''American Journal of Science'', vol. 45, January 1893.

* "Shall Cuba Be Free?," ''The Forum'', September 1895.

* ''Report of the Public Lands Commission.'' United States Government Printing Office, 1903–1905.

References

External links

USGS: The Four Great Surveys of the West

''Clarence King (1842–1901): Pioneering Geologist of the West'', Geological Society of America

''Biographical memoir of Clarence King, 1842–1901''

by Samuel Franklin Emmons.

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:King, Clarence American geologists American mountain climbers American art critics Explorers of the United States United States Geological Survey personnel 1842 births 1901 deaths History of the Sierra Nevada (United States) Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni Impostors Tuberculosis deaths in Arizona 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis Burials in Rhode Island Writers from Newport, Rhode Island