Civil disobediance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain

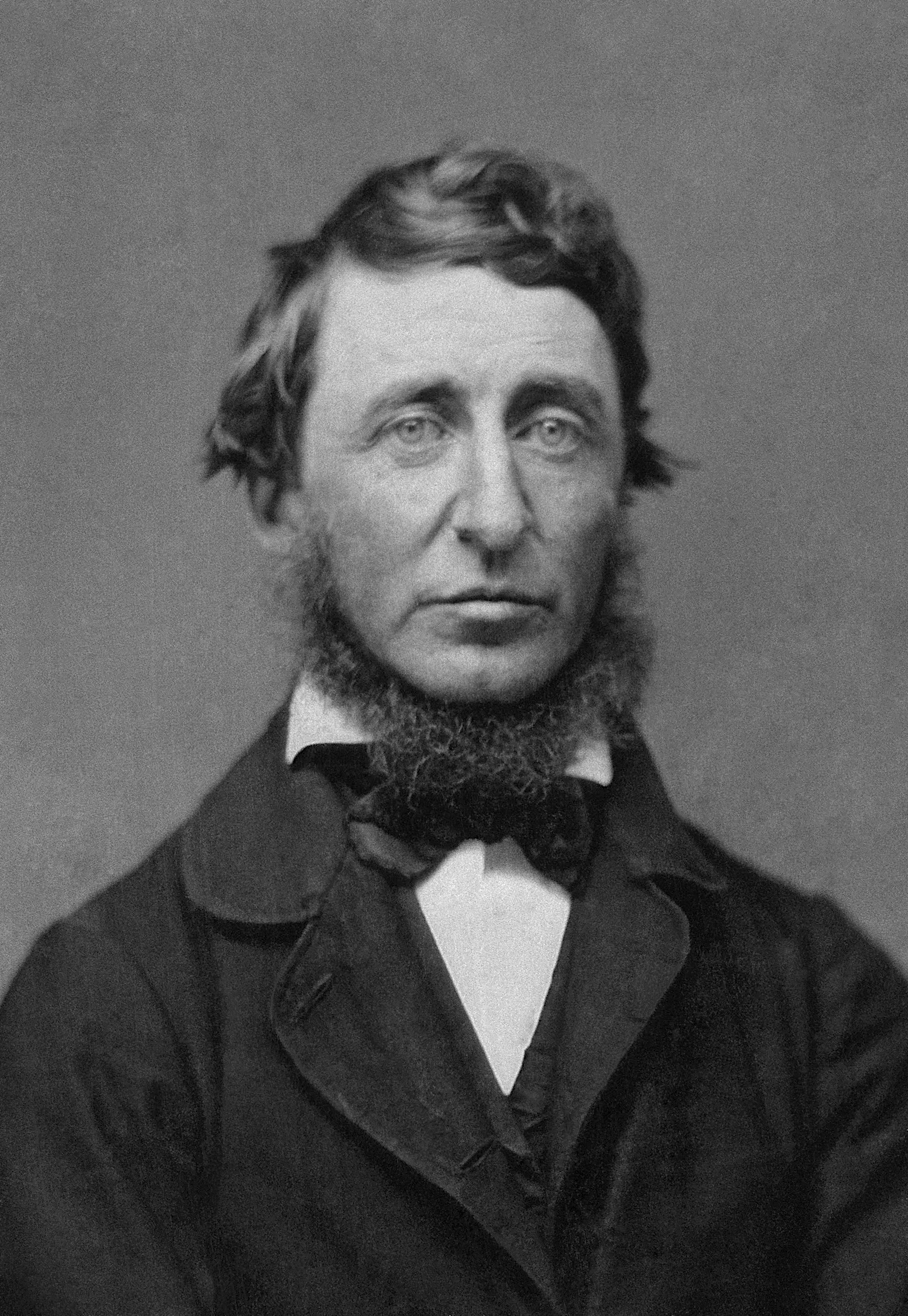

A version was taken up by the author Henry David Thoreau in his essay Civil Disobedience (Thoreau), ''Civil Disobedience'', and later by Gandhi in his doctrine of '' Satyagraha''. Gandhi's Satyagraha was partially influenced and inspired by Shelley's nonviolence in protest and political action. In particular, it is known that Gandhi often quoted Shelley's ''Masque of Anarchy'' to vast audiences during the campaign for a free India. Thoreau's 1849 essay '' Civil Disobedience'', originally titled "Resistance to Civil Government", has had a wide influence on many later practitioners of civil disobedience. The driving idea behind the essay is that citizens are morally responsible for their support of aggressors, even when such support is required by law. In the essay, Thoreau explained his reasons for having refused to pay taxes as an act of

Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government" was eventually renamed "Essay on Civil Disobedience". After his landmark lectures were published in 1866, the term began to appear in numerous sermons and lectures relating to slavery and the war in Mexico. Thus, by the time Thoreau's lectures were first published under the title "Civil Disobedience", in 1866, four years after his death, the term had achieved fairly widespread usage.

It has been argued that the term "civil disobedience" has always suffered from ambiguity and in modern times, become utterly debased. Marshall Cohen notes, "It has been used to describe everything from bringing a test-case in the federal courts to taking aim at a federal official. Indeed, for

Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government" was eventually renamed "Essay on Civil Disobedience". After his landmark lectures were published in 1866, the term began to appear in numerous sermons and lectures relating to slavery and the war in Mexico. Thus, by the time Thoreau's lectures were first published under the title "Civil Disobedience", in 1866, four years after his death, the term had achieved fairly widespread usage.

It has been argued that the term "civil disobedience" has always suffered from ambiguity and in modern times, become utterly debased. Marshall Cohen notes, "It has been used to describe everything from bringing a test-case in the federal courts to taking aim at a federal official. Indeed, for

A standing dilemma in Taksim

/ref>

Some disciplines of civil disobedience hold that the protester must submit to arrest and cooperate with the authorities. Others advocate falling limp or

Some disciplines of civil disobedience hold that the protester must submit to arrest and cooperate with the authorities. Others advocate falling limp or

online

woman suffrage in the United States in 1917. * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=January 2022 Activism by type Community organizing Direct action Dissent Nonviolence

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

s, demands, orders or commands of a government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

(or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

to be called "civil". Hence, civil disobedience is sometimes equated with peaceful protest

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, const ...

s or nonviolent resistance.

Henry David Thoreau's essay ''Resistance to Civil Government'', published posthumously as '' Civil Disobedience'', popularized the term in the US, although the concept itself has been practiced longer before. It has inspired leaders such as Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

of the U.S. women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement in the late 1800s, Saad Zaghloul

Saad Zaghloul ( ar, سعد زغلول / ; also ''Sa'd Zaghloul Pasha ibn Ibrahim'') (July 1859 – 23 August 1927) was an Egyptian revolutionary and statesman. He was the leader of Egypt's nationalist Wafd Party.

He led a civil disobedienc ...

in the 1910s culminating in Egyptian Revolution of 1919

The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 ( ''Thawra 1919'') was a countrywide revolution against the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan. It was carried out by Egyptians from different walks of life in the wake of the British-ordered exile of the r ...

against British Occupation, and Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

in 1920s India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

in their protests for Indian independence against the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

's and James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

's peaceful protests during the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in the 1960s United States contained important aspects of civil disobedience. Although civil disobedience is rarely justifiable in court, King regarded civil disobedience to be a display and practice of reverence for law: "Any man who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust and willingly accepts the penalty by staying in jail to arouse the conscience of the community on the injustice of the law is at that moment expressing the very highest respect for the law."

History

An early depiction of civil disobedience is inSophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

' play ''Antigone

In Greek mythology, Antigone ( ; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is the daughter of Oedipus and either his mother Jocasta or, in another variation of the myth, Euryganeia. She is a sister of Polynices, Eteocles, and Ismene.Roman, L., & R ...

'', in which Antigone

In Greek mythology, Antigone ( ; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is the daughter of Oedipus and either his mother Jocasta or, in another variation of the myth, Euryganeia. She is a sister of Polynices, Eteocles, and Ismene.Roman, L., & R ...

, one of the daughters of former King of Thebes, Oedipus, defies Creon Creon may refer to:

Greek history

* Creon, the first annual eponymous archon of Athens, 682–681 BC

Greek mythology

* Creon (king of Thebes), mythological king of Thebes

* Creon (king of Corinth), father of Creusa/Glauce in Euripides' ''Medea' ...

, the current King of Thebes, who is trying to stop her from giving her brother Polynices

In Greek mythology, Polynices (also Polyneices) (; grc, Πολυνείκης, Polyneíkes, lit= manifold strife' or 'much strife) was the son of Oedipus and either Jocasta or Euryganeia and the older brother of Eteocles (according to Sophocles ...

a proper burial. She gives a stirring speech in which she tells him that she must obey her conscience rather than human law. She is not at all afraid of the death he threatens her with (and eventually carries out), but she is afraid of how her conscience will smite her if she does not do this.

Étienne de La Boétie

Étienne or Estienne de La Boétie (; oc, Esteve de La Boetiá; 1 November 1530 – 18 August 1563) was a French magistrate, classicist, writer, poet and political theorist, best remembered for his intense and intimate friendship with essayist ...

's thought developed in his work '' Discours de la servitude volontaire ou le Contr'un'' (1552) was also taken up by many movements of civil disobedience, which drew from the concept of rebellion to voluntary servitude the foundation of its instrument of struggle. Étienne de La Boétie was one of the first to theorize and propose the strategy of non-cooperation, and thus a form of nonviolent disobedience, as a really effective weapon.

In the lead-up to the Glorious Revolution in Britain, when the 1689 Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights 1689 is an Act of the Parliament of England, which sets out certain basic civil rights and clarifies who would be next to inherit the Crown, and is seen as a crucial landmark in English constitutional law. It received Ro ...

was documented, the last Catholic monarch was deposed, and male and female joint-co-monarchs elevated. The English Midland Enlightenment had developed a manner of voicing objection to a law viewed as illegitimate and then taking the consequences of the law. This was focused on the illegitimacy of laws claimed to be "divine" in origin, both the "divine rights of kings" and "divine rights of man", and the legitimacy of laws acknowledged to be made by human beings.

Following the Peterloo massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

of 1819, the poet Percy Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

wrote the political poem ''The Mask of Anarchy

''The Masque of Anarchy'' (or ''The Mask of Anarchy'') is a British political poem written in 1819 (see 1819 in poetry) by Percy Bysshe Shelley following the Peterloo Massacre of that year. In his call for freedom, it is perhaps the first moder ...

'' later that year, that begins with the images of what he thought to be the unjust forms of authority of his time—and then imagines the stirrings of a new form of social action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes ...

. According to Ashton Nichols

Brooks Ashton Nichols (born 1953) is the Walter E. Beach ’56 Distinguished Chair Emeritus in Sustainable Studies and Professor of English Language and Literature Emeritus at Dickinson College. His interests are in literature, contemporary eco ...

, it is perhaps the first modern

Modern may refer to:

History

* Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Phil ...

statement of the principle of nonviolent protest.A version was taken up by the author Henry David Thoreau in his essay Civil Disobedience (Thoreau), ''Civil Disobedience'', and later by Gandhi in his doctrine of '' Satyagraha''. Gandhi's Satyagraha was partially influenced and inspired by Shelley's nonviolence in protest and political action. In particular, it is known that Gandhi often quoted Shelley's ''Masque of Anarchy'' to vast audiences during the campaign for a free India. Thoreau's 1849 essay '' Civil Disobedience'', originally titled "Resistance to Civil Government", has had a wide influence on many later practitioners of civil disobedience. The driving idea behind the essay is that citizens are morally responsible for their support of aggressors, even when such support is required by law. In the essay, Thoreau explained his reasons for having refused to pay taxes as an act of

protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of cooper ...

against slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and against the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. He writes,

If I devote myself to other pursuits and contemplations, I must first see, at least, that I do not pursue them sitting upon another man's shoulders. I must get off him first, that he may pursue his contemplations too. See what gross inconsistency is tolerated. I have heard some of my townsmen say, "I should like to have them order me out to help put down an insurrection of the slaves, or to march to Mexico;—see if I would go;" and yet these very men have each, directly by their allegiance, and so indirectly, at least, by their money, furnished a substitute.By the 1850s, a range of minority groups in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

: African Americans, Jews, Seventh Day Baptists, Catholics, anti-prohibitionists, racial egalitarians, and others—employed civil disobedience to combat a range of legal measures and public practices that to them promoted ethnic, religious, and racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

. Pro Public and typically peaceful resistance to political power remained an integral tactic in modern American minority rights

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

Civil-rights movements ...

politics.

In Ireland starting from 1879 the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

"Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

" intensified when Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

, in a speech in Ennis proposed that when dealing with tenants who take farms where another tenant was evicted, rather than resorting to violence, everyone in the locality should shun them. Following this Captain Charles Boycott

Charles Cunningham Boycott (12 March 1832 – 19 June 1897) was an English land agent whose ostracism by his local community in Ireland gave the English language the verb "to boycott". He had served in the British Army 39th Foot, which b ...

, the land agent of an absentee landlord in County Mayo, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, was subject to social ostracism

Ostracism ( el, ὀστρακισμός, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the ci ...

organized by the Irish Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farme ...

in 1880. Boycott attempted to evict eleven tenants from his land. While Parnell's speech did not refer to land agents or landlords, the tactic was applied to Boycott when the alarm was raised about the evictions. Despite the short-term economic hardship to those undertaking this action, Boycott soon found himself isolated – his workers stopped work in the fields and stables, as well as in his house. Local businessmen stopped trading with him, and the local postman refused to deliver mail. The movement spread throughout Ireland and gave rise to the term to Boycott, and eventually led to legal reform and support for Irish independence.

Egypt saw a massive implementation on a nation-wide movement starting 1914 and peaking in 1919 as the Egyptian Revolution of 1919. This was then adopted by other native peoples who objected to British occupation from 1920 and on. This was not used with native laws that were more oppressive than the British occupation, leading to problems for these countries today. Zaghloul Pasha, considered the mastermind behind this massive civil disobedience, was a native middle-class, Azhar graduate, political activist, judge, parliamentary and ex-cabinet minister whose leadership brought Christian and Muslim communities together as well as women into the massive protests. Along with his companions of Wafd Party

The Wafd Party (; ar, حزب الوفد, ''Ḥizb al-Wafd'') was a nationalist liberal political party in Egypt. It was said to be Egypt's most popular and influential political party for a period from the end of World War I through the 1930 ...

, who have achieved an independence of Egypt and a first constitution in 1923.

Civil disobedience is one of the many ways people have revolted against what they deem to be unfair laws. It has been used in many nonviolent resistance movements in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

's campaigns for independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

), in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

's Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

, in early stages of the Bangladeshi independence movement against Pakistani colonialism and in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

to oust their Stalinist government. In South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

during the leftist campaign against the far-right Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime, in the American civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United ...

against Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

, in the Singing Revolution

The Singing Revolution; lv, dziesmotā revolūcija; lt, dainuojanti revoliucija) was a series of events that led to the restoration of independence of the Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania from the Soviet Union at the end of ...

to bring independence to the Baltic countries

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone ...

from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and more recently with the 2003 Rose Revolution

The Rose Revolution or Revolution of Roses ( ka, ვარდების რევოლუცია, tr) was a nonviolent change of power that occurred in Georgia in November 2003. The event was brought about by widespread protests over the ...

in Georgia, the 2004 Orange Revolution

The Orange Revolution ( uk, Помаранчева революція, translit=Pomarancheva revoliutsiia) was a series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005, in the immediate afterm ...

and the 2013–2014 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine, the 2016–2017 Candlelight Revolution in South Korea, and the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests, among many other various movements worldwide.

Etymology

Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government" was eventually renamed "Essay on Civil Disobedience". After his landmark lectures were published in 1866, the term began to appear in numerous sermons and lectures relating to slavery and the war in Mexico. Thus, by the time Thoreau's lectures were first published under the title "Civil Disobedience", in 1866, four years after his death, the term had achieved fairly widespread usage.

It has been argued that the term "civil disobedience" has always suffered from ambiguity and in modern times, become utterly debased. Marshall Cohen notes, "It has been used to describe everything from bringing a test-case in the federal courts to taking aim at a federal official. Indeed, for

Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government" was eventually renamed "Essay on Civil Disobedience". After his landmark lectures were published in 1866, the term began to appear in numerous sermons and lectures relating to slavery and the war in Mexico. Thus, by the time Thoreau's lectures were first published under the title "Civil Disobedience", in 1866, four years after his death, the term had achieved fairly widespread usage.

It has been argued that the term "civil disobedience" has always suffered from ambiguity and in modern times, become utterly debased. Marshall Cohen notes, "It has been used to describe everything from bringing a test-case in the federal courts to taking aim at a federal official. Indeed, for Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second vice president to resign the position, the other being John ...

it has become a code-word describing the activities of muggers, arsonists, draft evaders, campaign hecklers, campus militants, anti-war demonstrators, juvenile delinquents and political assassins."

LeGrande writes that

He encourages a distinction between lawful protest demonstration, nonviolent civil disobedience, and violent civil disobedience.

In a letter to P. K. Rao, dated 10 September 1935, Gandhi disputes that his idea of civil disobedience was derived from the writings of Thoreau:

The statement that I had derived my idea of Civil Disobedience from the writings of Thoreau is wrong. The resistance to authority in South Africa was well advanced before I got the essay ... When I saw the title of Thoreau's great essay, I began to use his phrase to explain our struggle to the English readers. But I found that even "Civil Disobedience" failed to convey the full meaning of the struggle. I therefore adopted the phrase "Civil Resistance."

Theories

In seeking an active form of civil disobedience, one may choose to deliberately break certain laws, such as by forming a peaceful blockade or occupying a facility illegally, though sometimes violence has been known to occur. Often there is an expectation to be attacked or even beaten by the authorities. Protesters often undergo training in advance on how to react to arrest or to attack. Civil disobedience is usually defined as pertaining to a citizen's relation to the state and its laws, as distinguished from a constitutional impasse, in which two public agencies, especially two equally sovereign branches of government, conflict. For instance, if thehead of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, ...

of a country were to refuse to enforce a decision of that country's highest court, it would not be civil disobedience, since the head of government would act in his or her capacity as public official rather than private citizen.

This definition is disputed by Thoreau's political philosophy on the conscience vs. the collective. The person is the final judge of right and wrong. More than this, since only people act, only a person can act unjustly. When the government knocks on the door, it is a person in the form of a postman or tax collector whose hand hits the wood. Before Thoreau's imprisonment, when a confused taxman had wondered aloud about how to handle his refusal to pay, Thoreau had advised, "Resign". If a man chose to be an agent of injustice, then Thoreau insisted on confronting him with the fact that he was making a choice. He admits that government may express the will of the majority but it may also express nothing more than the will of elite politicians. Even a good form of government is "liable to be abused and perverted before the people can act through it". If a government did express the voice of most people, this would not compel the obedience of those who disagree with what is said. The majority may be powerful but it is not necessarily right.

In his 1971 book, ''A Theory of Justice

''A Theory of Justice'' is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distributi ...

'', John Rawls

John Bordley Rawls (; February 21, 1921 – November 24, 2002) was an American moral, legal and political philosopher in the liberal tradition. Rawls received both the Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy and the National Humanities Medal in ...

described civil disobedience as "a public, non-violent, conscientious yet political act contrary to law usually done with the aim of bringing about change in the law or policies of the government".

Ronald Dworkin held that there are three types of civil disobedience:

* "Integrity-based" civil disobedience occurs when a citizen disobeys a law they feel is immoral, as in the case of abolitionists disobeying the fugitive slave laws

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from th ...

by refusing to turn over escaped slaves to authorities.

* "Justice-based" civil disobedience occurs when a citizen disobeys laws to lay claim to some right denied to them, as when Black people illegally protested during the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

.

* "Policy-based" civil disobedience occurs when a person breaks the law to change a policy they believe is dangerously wrong.

Some theories of civil disobedience hold that civil disobedience is only justified against governmental entities. Brownlee argues that disobedience in opposition to the decisions of non-governmental agencies such as trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s, banks, and private universities

Private universities and private colleges are institutions of higher education, not operated, owned, or institutionally funded by governments. They may (and often do) receive from governments tax breaks, public student loans, and grants. Depe ...

can be justified if it reflects "a larger challenge to the legal system that permits those decisions to be taken". The same principle, she argues, applies to breaches of law in protest against international organization

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states a ...

s and foreign governments.

It is usually recognized that lawbreaking, if it is not done publicly, at least must be publicly announced to constitute civil disobedience. But Stephen Eilmann argues that if it is necessary to disobey rules that conflict with morality, we might ask why disobedience should take the form of public civil disobedience rather than simply covert lawbreaking. If a lawyer wishes to help a client overcome legal obstacles to securing their natural right

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' an ...

s, he might, for instance, find that assisting in fabricating evidence or committing perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

is more effective than open disobedience. This assumes that common morality does not have a prohibition on deceit

Deception or falsehood is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight o ...

in such situations. The Fully Informed Jury Association's publication "A Primer for Prospective Jurors" notes, "Think of the dilemma faced by German citizens when Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of ...

demanded to know if they were hiding a Jew in their house." By this definition, civil disobedience could be traced back to the Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

, where Shiphrah

Shiphrah ( he, שִׁפְרָה ') and Puah ( he, פּוּעָה ') were two midwives who briefly prevented a genocide of children by the Egyptians, according to Exodus 1:15–21. According to the Exodus narrative, they were commanded by the ...

and Puah refused a direct order of Pharaoh but misrepresented how they did it. (Exodus 1: 15–19)

Violent vs. nonviolent

There have been debates as to whether civil disobedience must necessarily be non-violent. '' Black's Law Dictionary'' includes nonviolence in its definition of civil disobedience. Christian Bay's encyclopedia article states that civil disobedience requires "carefully chosen and legitimate means", but holds that they do not have to be non-violent. It has been argued that, while both civil disobedience and civil rebellion are justified by appeal to constitutional defects, rebellion is much more destructive; therefore, the defects justifying rebellion must be much more serious than those justifying disobedience, and if one cannot justify civil rebellion, then one cannot justify a civil disobedient's use of force and violence and refusal to submit to arrest. Civil disobedients' refraining from violence is also said to help preserve society's tolerance of civil disobedience. The philosopher H. J. McCloskey argues that "if violent, intimidatory, coercive disobedience is more effective, it is, other things being equal, more justified than less effective, nonviolent disobedience." In his best-selling ''Disobedience and Democracy: Nine Fallacies on Law and Order'',Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian, playwright, philosopher, socialist thinker and World War II veteran. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a politica ...

takes a similar position; Zinn states that while the goals of civil disobedience are generally nonviolent,

Zinn rejects any "easy and righteous dismissal of violence", noting that Thoreau, the popularizer of the term civil disobedience, approved of the armed insurrection of John Brown. He also notes that some major civil disobedience campaigns which have been classified as non-violent, such as the Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts o ...

, have actually included elements of violence.

Revolutionary vs. non-revolutionary

Non-revolutionary civil disobedience is a simple disobedience of laws on the grounds that they are judged "wrong" by a person's conscience, or as part of an effort to render certain laws ineffective, to cause their repeal, or to exert pressure to get one's political wishes on some other issue. Revolutionary civil disobedience is more of an active attempt to overthrow a government (or to change cultural traditions, social customs or religious beliefs). Revolution does not have to be political, i.e. "cultural revolution", it simply implies sweeping and widespread change to a section of the social fabric. Gandhi's acts have been described as revolutionary civil disobedience. It has been claimed that theHungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

under Ferenc Deák directed revolutionary civil disobedience against the Austrian government. Thoreau also wrote of civil disobedience accomplishing "peaceable revolution". Howard Zinn, Harvey Wheeler

John Harvey Wheeler (October 17, 1918 – September 6, 2004) was an American author, political scientist, and scholar. He was best known as co-author with Eugene Burdick of ''Fail-Safe'' (1962), an early Cold War novel that depicted what could ...

, and others have identified the right espoused in the US Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

to "alter or abolish" an unjust government to be a principle of civil disobedience.

Collective vs. solitary

The earliest recorded incidents of collective civil disobedience took place during theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. Unarmed Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s gathered in the streets to prevent the installation of pagan images in the Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two now-destroyed religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jeru ...

. In modern times, some activists who commit civil disobedience as a group collectively refuse to sign bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

until certain demands are met, such as favourable bail conditions, or the release of all the activists. This is a form of jail solidarity. There have also been many instances of solitary civil disobedience, such as that committed by Thoreau, but these sometimes go unnoticed. Thoreau, at the time of his arrest, was not yet a well-known author, and his arrest was not covered in any newspapers in the days, weeks and months after it happened. The tax collector who arrested him rose to higher political office, and Thoreau's essay was not published until after the end of the Mexican War.

Choices

Action

Civil disobedients have chosen a variety of different illegal acts. Hugo A. Bedau writes, Bedau also notes, though, that the very harmlessness of such entirely symbolic illegal protests towardpublic policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public p ...

goals may serve a propaganda purpose. Some civil disobedients, such as the proprietors of illegal medical cannabis dispensaries

Medical cannabis, or medical marijuana (MMJ), is cannabis and cannabinoids that are prescribed by physicians for their patients. The use of cannabis as medicine has not been rigorously tested due to production and governmental restrictions ...

and Voice in the Wilderness, which brought medicine to Iraq without the permission of the US government, directly achieve a desired social goal (such as the provision of medication to the sick) while openly breaking the law. Julia Butterfly Hill

''Sequoia sempervirens'' ()''Sunset Western Garden Book,'' 1995:606–607 is the sole living species of the genus '' Sequoia'' in the cypress family Cupressaceae (formerly treated in Taxodiaceae). Common names include coast redwood, coastal ...

lived in Luna

Luna commonly refers to:

* Earth's Moon, named "Luna" in Latin

* Luna (goddess), the ancient Roman personification of the Moon

Luna may also refer to:

Places Philippines

* Luna, Apayao

* Luna, Isabela

* Luna, La Union

* Luna, San Jose

Roma ...

, a -tall, 600-year-old California Redwood tree for 738 days, preventing its felling.

In cases where the criminalized behaviour is pure speech

Pure

Pure may refer to:

Computing

* A pure function

* A pure virtual function

* PureSystems, a family of computer systems introduced by IBM in 2012

* Pure Software, a company founded in 1991 by Reed Hastings to support the Purify tool

* Pure-F ...

, civil disobedience can consist simply of engaging in the forbidden speech. An example is WBAI

WBAI (99.5 FM) is a non-commercial, listener-supported radio station licensed to New York, New York. Its programming is a mixture of political news, talk and opinion from a left-leaning, liberal or progressive viewpoint, and eclectic music. ...

's broadcasting of the bit " Filthy Words" from a George Carlin

George Denis Patrick Carlin (May 12, 1937 – June 22, 2008) was an American comedian, actor, author, and social critic. Regarded as one of the most important and influential stand-up comedians of all time, he was dubbed "the dean of countercu ...

comedy album, which eventually led to the 1978 Supreme Court case of '' FCC v. Pacifica Foundation''. Threatening government officials is another classic way of expressing defiance toward the government and unwillingness to stand for its policies. For example, Joseph Haas was arrested for allegedly sending an email to the Lebanon, New Hampshire

Lebanon is a city in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 14,282 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, up from 13,151 at the 2010 census. Lebanon is in western New Hampshire, south of Hanover, New Hampshire, H ...

, city councillors stating, "Wise up or die."

More generally, protesters of particular victimless crime

A victimless crime is an illegal act that typically either directly involves only the perpetrator or occurs between consenting adults. Because it is consensual in nature, whether there involves a victim is a matter of debate. Definitions of vi ...

s often see fit to openly commit that crime. Laws against public nudity, for instance, have been protested by going naked in public, and laws against cannabis consumption have been protested by openly possessing it and using it at cannabis rallies.

Some forms of civil disobedience, such as illegal boycotts, refusals to pay taxes, draft dodging, distributed denial-of-service attacks, and sit-ins, make it more difficult for a system to function. In this way, they might be considered coercive; coercive disobedience has the effect of exposing the enforcement of laws and policies, and it has even operated as an aesthetic strategy in contemporary art practice. Brownlee notes that "although civil disobedients are constrained in their use of coercion by their conscientious aim to engage in moral dialogue, nevertheless they may find it necessary to employ limited coercion to get their issue onto the table". The Plowshares organization temporarily closed GCSB Waihopai

The Waihopai Station is a secure communication facility, located near Blenheim, New Zealand, Blenheim, run by New Zealand's Government Communications Security Bureau. The station started operating in 1989, and collects data that is then shared wi ...

by padlocking the gates and using sickles to deflate one of the large domes covering two satellite dishes.

Electronic civil disobedience

Electronic civil disobedience (ECD; also known as cyber civil disobedience or cyber disobedience) can refer to any type of civil disobedience in which the participants use information technology to carry out their actions. Electronic civil disob ...

can include web site defacements, redirect

Redirect and its variants (e.g., redirection) may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Redirect'', 2012 Christian metal album and its title track by Your Memorial

* ''Redirected'' (film), a 2014 action comedy film

Computing

* ICMP R ...

s, denial-of-service attack

In computing, a denial-of-service attack (DoS attack) is a cyber-attack in which the perpetrator seeks to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users by temporarily or indefinitely disrupting services of a host conn ...

s, information theft and data leaks, illegal web site parodies

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its sub ...

, virtual sit-ins, and virtual sabotage. It is distinct from other kinds of hacktivism

In Internet activism, hacktivism, or hactivism (a portmanteau of ''hack'' and ''activism''), is the use of computer-based techniques such as hacking as a form of civil disobedience to promote a political agenda or social change. With roots in hac ...

in that the perpetrator openly reveals his identity. Virtual actions rarely succeed in completely shutting down their targets, but they often generate significant media attention.

Dilemma actions are designed to create a "response dilemma" for public authorities "by forcing them to either concede some public space to protesters or make themselves look absurd or heavy-handed by acting against the protest."Laura Moth, Today's Zaman, 19 June 2013A standing dilemma in Taksim

/ref>

Compliance

Some disciplines of civil disobedience hold that the protester must submit to arrest and cooperate with the authorities. Others advocate falling limp or

Some disciplines of civil disobedience hold that the protester must submit to arrest and cooperate with the authorities. Others advocate falling limp or resisting arrest

Resisting arrest, or simply resisting, is an illegal act of a suspected criminal either fleeing, threatening, assaulting, or providing a fake ID to a police officer during arrest. In most cases, the person responsible for resisting arrest is crimi ...

, especially when it will hinder the police from effectively responding to a mass protest.

Many of the same decisions and principles that apply in other criminal investigations and arrests arise also in civil disobedience cases. For example, the suspect may need to decide whether to grant a consent search

Consent searches (or consensual searches) are searches made by police officers in the United States based on the voluntary consent of the individual whose person or property is being searched. The simplest and most common type of warrantless sear ...

of his property, and whether to talk to police officers. It is generally agreed within the legal community, and is often believed within the activist community, that a suspect's talking to criminal investigators can serve no useful purpose, and may be harmful. Some civil disobedients are compelled to respond to investigators' questions, sometimes by a misunderstanding of the legal ramifications or a fear of seeming rude. Also, some civil disobedients seek to use the arrest as an opportunity to make an impression on the officers. Thoreau wrote,

Some civil disobedients feel it is incumbent upon them to accept punishment because of their belief in the validity of the social contract, which is held to bind all to obey the laws that a government meeting certain standards of legitimacy has established, or else suffer the penalties set out in the law. Other civil disobedients who favour the existence of government still do not believe in the legitimacy of their particular government or do not believe in the legitimacy of a particular law it has enacted. Anarchistic civil disobedients do not believe in the legitimacy of any government, so see no need to accept punishment for a violation of criminal law.

Plea

An important decision for civil disobedients is whether toplead guilty

In legal terms, a plea is simply an answer to a claim made by someone in a criminal case under common law using the adversarial system. Colloquially, a plea has come to mean the assertion by a defendant at arraignment, or otherwise in response ...

. There is much debate on this point, as some believe that it is a civil disobedient's duty to submit to the punishment prescribed by law, while others believe that defending oneself in court will increase the possibility of changing the unjust law. It has also been argued that either choice is compatible with the spirit of civil disobedience. ACT UP's Civil Disobedience Training handbook states that a civil disobedient who pleads guilty is essentially stating, "Yes, I committed the act of which you accuse me. I don't deny it; in fact, I am proud of it. I feel I did the right thing by violating this particular law; I am guilty as charged", but that pleading not guilty sends a message of, "Guilt implies wrong-doing. I feel I have done no wrong. I may have violated some specific laws, but I am guilty of doing no wrong. I, therefore, plead not guilty." A plea of no contest

' is a legal term that comes from the Latin phrase for "I do not wish to contend". It is also referred to as a plea of no contest or no defense.

In criminal trials in certain United States jurisdictions, it is a plea where the defendant neith ...

is sometimes regarded as a compromise between the two. One defendant accused of illegally protesting nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced ...

, when asked to enter his plea, stated, "I plead for the beauty that surrounds us"; this is known as a "creative plea", and will usually be interpreted as a plea of not guilty.

When the Committee for Non-Violent Action sponsored a protest in August 1957, at the Camp Mercury nuclear test site near Las Vegas, Nevada, 13 of the protesters attempted to enter the test site knowing that they faced arrest. At an announced time, one by one they crossed a line and were immediately arrested. They were put on a bus and taken to the Nye County seat of Tonopah, Nevada, and arraigned for trial before the local Justice of the Peace, that afternoon. A civil rights attorney, Francis Heisler, had volunteered to defend the accused, advising them to plead '' nolo contendere'' rather than guilty or not guilty. They were found guilty and given suspended sentences, conditional on not reentering the test site.

Howard Zinn writes,

Sometimes the prosecution proposes a plea bargain to civil disobedients, as in the case of the Camden 28

The Camden 28 were a group of leftist, Catholic, anti-Vietnam War activists who in 1971 planned and executed a raid on a draft board in Camden, New Jersey, United States. The raid resulted in a high-profile criminal trial of the activists tha ...

, in which the defendants were offered an opportunity to plead guilty to one misdemeanour count and receive no jail time. In some mass arrest

A mass arrest occurs when police apprehend large numbers of suspects at once. This sometimes occurs at protests. Some mass arrests are also used in an effort to combat gang activity. This is sometimes controversial, and lawsuits sometimes result. I ...

situations, the activists decide to use solidarity tactics to secure the same plea bargain for everyone. But some activists have opted to enter a blind plea, pleading guilty without any plea agreement in place. Mahatma Gandhi pleaded guilty and told the court, "I am here to ... submit cheerfully to the highest penalty that can be inflicted upon me for what in law is a deliberate crime and what appears to me to be the highest duty of a citizen."

Allocution

Some civil disobedience defendants choose to make a defiant speech, or a speech explaining their actions, inallocution

An allocution, or allocutus, is a formal statement made to the court by the defendant who has been found guilty prior to being sentenced. It is part of the criminal procedure in some jurisdictions using common law.

Concept

An allocution allo ...

. In ''U.S. v. Burgos-Andujar'', a defendant who was involved in a movement to stop military exercises by trespassing on US Navy property argued to the court in allocution that "the ones who are violating the greater law are the members of the Navy". As a result, the judge increased her sentence from 40 to 60 days. This action was upheld because, according to the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, her statement suggested a lack of remorse, an attempt to avoid responsibility for her actions, and even a likelihood of repeating her illegal actions. Some of the other allocution speeches given by the protesters complained about mistreatment from government officials.

Tim DeChristopher

Timothy Mansfield DeChristopher (born November 18, 1981) is an American climate activist and co-founder of the environmental group Peaceful Uprising. In December 2008, he protested a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) oil and gas lease auction of 1 ...

gave an allocution statement to the court describing the US as "a place where the rule of law was created through acts of civil disobedience" and arguing, "Since those bedrock acts of civil disobedience by our founding fathers, the rule of law in this country has continued to grow closer to our shared higher moral code through the civil disobedience that drew attention to legalized injustice."

Legal implications

Steven Barkan writes that if defendants plead not guilty, "they must decide whether their primary goal will be to win an acquittal and avoid imprisonment or a fine, or to use the proceedings as a forum to inform the jury and the public of the political circumstances surrounding the case and their reasons for breaking the law via civil disobedience." A technical defence may enhance the chances for acquittal but increase the possibility of additional proceedings and of reduced press coverage. During theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

era, the Chicago Eight

The Chicago Seven, originally the Chicago Eight and also known as the Conspiracy Eight or Conspiracy Seven, were seven defendants—Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and Lee Weiner—charged b ...

used a political defence, but Benjamin Spock

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903 – March 15, 1998) was an American pediatrician and left-wing political activist whose book '' Baby and Child Care'' (1946) is one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century, selling 500,000 copies ...

used a technical defence. In countries such as the United States, whose laws guarantee the right to a jury trial

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significan ...

but do not excuse lawbreaking for political purposes, some civil disobedients seek jury nullification

Jury nullification (US/UK), jury equity (UK), or a perverse verdict (UK) occurs when the jury in a criminal trial gives a not guilty verdict despite a defendant having clearly broken the law. The jury's reasons may include the belief that the ...

. Over the years, this has been made more difficult by court decisions such as '' Sparf v. United States'', which held that the judge need not inform jurors of their nullification prerogative, and '' United States v. Dougherty'', which held that the judge need not allow defendants to openly seek jury nullification.

Governments have generally not recognized the legitimacy of civil disobedience or viewed political objectives as an excuse for breaking the law. Specifically, the law usually distinguishes between criminal motive and criminal intent; the offender's motives or purposes may be admirable and praiseworthy, but his intent may still be criminal. Hence the saying that "if there is any possible justification of civil disobedience it must come from outside the legal system."

One theory is that, while disobedience may be helpful, any great amount of it undermines the law by encouraging general disobedience which is neither conscientious nor of social benefit. Therefore, conscientious lawbreakers must be punished. Michael Bayles argues that if a person violates a law to create a test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

as to the constitutionality

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

of a law, and then wins his case, then that act did not constitute civil disobedience. It has also been argued that breaking the law for self-gratification, as in the case of a cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: '' Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternative ...

user who does not direct his act at securing the repeal of amendment of the law, is not civil disobedience. Likewise, a protester who attempts to escape punishment by committing the crime covertly and avoiding attribution, or by denying having committed the crime, or by fleeing the jurisdiction, is generally not called a civil disobedient.

Courts have distinguished between two types of civil disobedience: "Indirect civil disobedience involves violating a law which is not, itself, the object of protest, whereas direct civil disobedience involves protesting the existence of a particular law by breaking that law." During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, courts typically refused to excuse the perpetrators of illegal protests from punishment on the basis of their challenging the legality of the Vietnam War; the courts ruled it was a political question

In United States constitutional law, the political question doctrine holds that a constitutional dispute that requires knowledge of a non-legal character or the use of techniques not suitable for a court or explicitly assigned by the Constitution ...

. The necessity

Necessary or necessity may refer to:

* Need

** An action somebody may feel they must do

** An important task or essential thing to do at a particular time or by a particular moment

* Necessary and sufficient condition, in logic, something that i ...

defence has sometimes been used as a shadow defence by civil disobedients to deny guilt without denouncing their politically motivated acts, and to present their political beliefs in the courtroom. Court cases such as '' United States v. Schoon'' have greatly curtailed the availability of the political necessity defence. Likewise, when Carter Wentworth was charged for his role in the Clamshell Alliance

The Clamshell Alliance is an anti-nuclear organization founded in 1976 to oppose the Seabrook Station nuclear power plant in the U.S. state of New Hampshire. The alliance has been dormant for many years.

The group was co-founded by Paul Gunter, ...

's 1977 illegal occupation of the Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant

The Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, more commonly known as Seabrook Station, is a nuclear power plant located in Seabrook, New Hampshire, United States, approximately north of Boston and south of Portsmouth. It has operated since 1990. With its ...

, the judge instructed the jury to disregard his competing harms Competing harms is a legal doctrine in certain U.S. states, particularly in New England. For example, the Maine Criminal Code holds that "Conduct that the person believes to be necessary to avoid imminent physical harm to that person or another is j ...

defence, and he was found guilty. Fully Informed Jury Association activists have sometimes handed out educational leaflets inside courthouses despite admonitions not to; according to the association, many of them have escaped prosecution because "prosecutors have reasoned (correctly) that if they arrest fully informed jury leafleters, the leaflets will have to be given to the leafleter's own jury as evidence."

Along with giving the offender his just deserts

Desert () in philosophy is the condition of being deserving of something, whether good or bad. It is sometimes called moral desert to clarify the intended usage and distinguish it from the dry desert biome. It is a concept often associated wi ...

, achieving crime control

Crime control refers to methods taken to reduce crime in a society. Crime control standardizes police work. Crime prevention is also widely implemented in some countries, through government police and, in many cases, private policing methods such ...

via incapacitation and deterrence

Deterrence may refer to:

* Deterrence theory, a theory of war, especially regarding nuclear weapons

* Deterrence (penology), a theory of justice

* Deterrence (psychology)

Deterrence in relation to criminal offending is the idea or theory that t ...

is a major goal of criminal punishment

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other ...

. Brownlee argues, "Bringing in deterrence at the level of justification detracts from the law's engagement in a moral dialogue with the offender as a rational person because it focuses attention on the threat of punishment and not the moral reasons to follow this law." British judge Lord Hoffman

Leonard Hubert "Lennie" Hoffmann, Baron Hoffmann (born 8 May 1934) is a retired senior South African–British judge. He served as a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary from 1995 to 2009.

Well known for his lively decisions and willingness to break ...

writes, "In deciding whether or not to impose punishment, the most important consideration would be whether it would do more harm than good. This means that the objector has no right not to be punished. It is a matter for the state (including the judges) to decide on utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

grounds whether to do so or not." Hoffman also asserted that while the "rules of the game" for protesters were to remain non-violent while breaking the law, the authorities must recognize that demonstrators are acting out of their conscience in pursuit of democracy. "When it comes to punishment, the court should take into account their personal convictions", he said.

See also

*Anti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine ''New Statesman'' ...

* Agorism

* Astroturfing

* Billboard hacking

Billboard hacking or billboard hijacking is the illegal practice of altering a billboard without the consent of the owner. It may involve physically pasting new media over the existing image, or hacking into the system used to control electronic ...

* Civil resistance

* Civilian-based defense Civilian-based defense or social defence describes non-military action by a society or social group, particularly in a context of a sustained campaign against outside attack or dictatorial rule – or preparations for such a campaign in the event of ...

* Climate disobedience

Individual action on climate change can include personal choices in many areas, such as diet, travel, household energy use, consumption of goods and services, and family size. Individuals can also engage in local and political advocacy around issu ...

* Colour revolution

Colour revolution (sometimes coloured revolution) is a term used since around 2004 by worldwide media to describe various anti-regime protest movements and accompanying (attempted or successful) changes of government that took place in pos ...

* Conscientious objector

* Counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

* Counter-economics

Counter-economics is an economic theory and revolutionary method consisting of direct action carried out through the black market or the gray market. As a term, it was originally used by American libertarian activists and theorists Samuel Edward ...

* Culture jamming

Culture jamming (sometimes also guerrilla communication) is a form of protest used by many anti-consumerist social movements to disrupt or subvert media culture and its mainstream cultural institutions, including corporate advertising. It att ...

* Demonstration

* Dissent

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

* Direct action

* Diversity of tactics

Diversity of tactics is a phenomenon wherein a social movement makes periodic use of force for disruptive or defensive purposes, stepping beyond the limits of nonviolent resistance, but also stopping short of total militarization. It also refe ...

* Ecoterrorism

Eco-terrorism is an act of violence which is committed in support of environmentalism, environmental causes, against people or property.

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines eco-terrorism as "...the use or threatened ...

* Extinction Rebellion

Extinction Rebellion (abbreviated as XR) is a global environmental movement, with the stated aim of using nonviolent civil disobedience to compel government action to avoid tipping points in the climate system, biodiversity loss, and the risk o ...

* Gene Sharp

Gene Sharp (January 21, 1928 – January 28, 2018) was an American political scientist. He was the founder of the Albert Einstein Institution, a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the study of nonviolent action, and professor of pol ...

* Grassroots

* Grey market

A grey market or dark market (sometimes confused with the similar term " parallel market") is the trade of a commodity through distribution channels that are not authorized by the original manufacturer or trade mark proprietor. Grey market pr ...

* Hunt sabotage Hunt sabotage is the direct action that animal rights activists and animal liberation activists undertake to interfere with hunting activity.

Anti-hunting campaigners are divided into hunt saboteurs and anti-hunt monitors to monitor for cruelty a ...

* Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

* Insubordination

Insubordination is the act of willfully disobeying a lawful order of one's superior. It is generally a punishable offense in hierarchical organizations such as the armed forces, which depend on people lower in the chain of command obeying ord ...

* Internet activism

Internet activism is the use of electronic communication technologies such as social media, e-mail, and podcasts for various forms of activism to enable faster and more effective communication by citizen movements, the delivery of particular inf ...

* Malicious compliance

Malicious compliance (also known as malicious obedience) is the behavior of strictly following the orders of a superior despite knowing that compliance with the orders will have an unintended or negative result. The term usually implies following ...

* Mass incidents in China

* Minority influence

Minority influence, a form of social influence, takes place when a member of a minority group influences the majority to accept the minority's beliefs or behavior. This occurs when a small group or an individual acts as an agent of social change by ...

* Nonconformism

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

to the established Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

* Non-conformists of the 1930s

The non-conformists of the 1930s were groups and individuals during the inter-war period in France that were seeking new solutions to face the political, economical and social crisis. The name was coined in 1969 by the historian Jean-Louis Loubet ...

* Nonviolent resistance

* Nonviolent revolution

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution conducted primarily by unarmed civilians using tactics of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritarian ...

* Off-the-grid

Off-the-grid or off-grid is a characteristic of buildings and a lifestyle designed in an independent manner without reliance on one or more public utilities. The term "off-the-grid" traditionally refers to not being connected to the electrical gr ...

* Protest art

Protest art is the creative works produced by activists and social movements. It is a traditional means of communication, utilized by a cross section of collectives and the state to inform and persuade citizens. Protest art helps arouse base emot ...

* Satyagraha

* Tree sitting

Tree sitting is a form of environmentalist civil disobedience in which a protester sits in a tree, usually on a small platform built for the purpose, to protect it from being cut down (speculating that loggers will not endanger human lives by cutt ...

* Underground culture

Underground culture, or simply underground, is a term to describe various alternative cultures which either consider themselves different from the mainstream of society and culture, or are considered so by others. The word "underground" is used ...

* User revolt

References

Further reading

* * Dodd, Lynda G. "Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship." ''Journal of Law and Politics'' 24 (2008): 339–433online

woman suffrage in the United States in 1917. * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=January 2022 Activism by type Community organizing Direct action Dissent Nonviolence