Civil War in Finland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''

The Finnish labour movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from

The Finnish labour movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from

The Second Period of Russification was halted on 15 March 1917 by the February Revolution, which removed the tsar,

The Second Period of Russification was halted on 15 March 1917 by the February Revolution, which removed the tsar,

The passing of the Tokoi Senate bill called the "Law of Supreme Power" (, more commonly known as ''valtalaki''; ) in July 1917, triggered one of the key crises in the power struggle between the social democrats and the conservatives. The fall of the Russian Empire opened the question of who would hold sovereign political authority in the former Grand Duchy. After decades of political disappointment, the February Revolution offered the Finnish social democrats an opportunity to govern; they held the absolute majority in Parliament. The conservatives were alarmed by the continuous increase of the socialists' influence since 1899, which reached a climax in 1917.

The "Law of Supreme Power" incorporated a plan by the socialists to substantially increase the authority of Parliament, as a reaction to the non-parliamentary and conservative leadership of the Finnish Senate between 1906 and 1916. The bill furthered Finnish autonomy in domestic affairs: the Russian Provisional Government was only allowed the right to control Finnish foreign and military policies. The Act was adopted with the support of the Social Democratic Party, the Agrarian League, part of the Young Finnish Party and some activists eager for Finnish sovereignty. The conservatives opposed the bill and some of the most right-wing representatives resigned from Parliament.

In Petrograd, the social democrats' plan had the backing of the Bolsheviks. They had been plotting a revolt against the Provisional Government since April 1917, and pro-Soviet demonstrations during the

The passing of the Tokoi Senate bill called the "Law of Supreme Power" (, more commonly known as ''valtalaki''; ) in July 1917, triggered one of the key crises in the power struggle between the social democrats and the conservatives. The fall of the Russian Empire opened the question of who would hold sovereign political authority in the former Grand Duchy. After decades of political disappointment, the February Revolution offered the Finnish social democrats an opportunity to govern; they held the absolute majority in Parliament. The conservatives were alarmed by the continuous increase of the socialists' influence since 1899, which reached a climax in 1917.

The "Law of Supreme Power" incorporated a plan by the socialists to substantially increase the authority of Parliament, as a reaction to the non-parliamentary and conservative leadership of the Finnish Senate between 1906 and 1916. The bill furthered Finnish autonomy in domestic affairs: the Russian Provisional Government was only allowed the right to control Finnish foreign and military policies. The Act was adopted with the support of the Social Democratic Party, the Agrarian League, part of the Young Finnish Party and some activists eager for Finnish sovereignty. The conservatives opposed the bill and some of the most right-wing representatives resigned from Parliament.

In Petrograd, the social democrats' plan had the backing of the Bolsheviks. They had been plotting a revolt against the Provisional Government since April 1917, and pro-Soviet demonstrations during the

At the end of November 1917, the moderate socialists among the social democrats won a second vote over the radicals in a debate over revolutionary versus parliamentary means, but when they tried to pass a resolution to completely abandon the idea of a socialist revolution, the party representatives and several influential leaders voted it down. The Finnish labour movement wanted to sustain a military force of its own and to keep the revolutionary road open, too. The wavering Finnish socialists disappointed V. I. Lenin and in turn, he began to encourage the Finnish Bolsheviks in Petrograd.

Among the labour movement, a more marked consequence of the events of 1917 was the rise of the Workers' Order Guards. There were 20–60 separate guards between 31 August and 30 September 1917, but on 20 October, after defeat in parliamentary elections, the Finnish labour movement proclaimed the need to establish more worker units. The announcement led to a rush of recruits: on 31 October the number of guards was 100–150; 342 on 30 November 1917 and 375 on 26 January 1918. Since May 1917, the paramilitary organisations of the left had grown in two phases, the majority of them as Workers' Order Guards. The minority were Red Guards, these were partly underground groups formed in industrialised towns and industrial centres, such as

At the end of November 1917, the moderate socialists among the social democrats won a second vote over the radicals in a debate over revolutionary versus parliamentary means, but when they tried to pass a resolution to completely abandon the idea of a socialist revolution, the party representatives and several influential leaders voted it down. The Finnish labour movement wanted to sustain a military force of its own and to keep the revolutionary road open, too. The wavering Finnish socialists disappointed V. I. Lenin and in turn, he began to encourage the Finnish Bolsheviks in Petrograd.

Among the labour movement, a more marked consequence of the events of 1917 was the rise of the Workers' Order Guards. There were 20–60 separate guards between 31 August and 30 September 1917, but on 20 October, after defeat in parliamentary elections, the Finnish labour movement proclaimed the need to establish more worker units. The announcement led to a rush of recruits: on 31 October the number of guards was 100–150; 342 on 30 November 1917 and 375 on 26 January 1918. Since May 1917, the paramilitary organisations of the left had grown in two phases, the majority of them as Workers' Order Guards. The minority were Red Guards, these were partly underground groups formed in industrialised towns and industrial centres, such as

The disintegration of Russia offered Finns a historic opportunity to gain national independence. After the October Revolution, the conservatives were eager for secession from Russia in order to control the left and minimise the influence of the Bolsheviks. The socialists were skeptical about sovereignty under conservative rule, but they feared a loss of support among nationalistic workers, particularly after having promised increased national liberty through the "Law of Supreme Power". Eventually, both political factions supported an independent Finland, despite strong disagreement over the composition of the nation's leadership.

Nationalism had become a "civic religion" in Finland by the end of nineteenth century, but the goal during the general strike of 1905 was a return to the autonomy of 1809–1898, not full independence. In comparison to the unitary Swedish regime, the domestic power of Finns had increased under the less uniform Russian rule. Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the

The disintegration of Russia offered Finns a historic opportunity to gain national independence. After the October Revolution, the conservatives were eager for secession from Russia in order to control the left and minimise the influence of the Bolsheviks. The socialists were skeptical about sovereignty under conservative rule, but they feared a loss of support among nationalistic workers, particularly after having promised increased national liberty through the "Law of Supreme Power". Eventually, both political factions supported an independent Finland, despite strong disagreement over the composition of the nation's leadership.

Nationalism had become a "civic religion" in Finland by the end of nineteenth century, but the goal during the general strike of 1905 was a return to the autonomy of 1809–1898, not full independence. In comparison to the unitary Swedish regime, the domestic power of Finns had increased under the less uniform Russian rule. Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the  Svinhufvud's Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917 and Parliament adopted it on 6 December. The social democrats voted against the Senate's proposal, while presenting an alternative declaration of sovereignty. The establishment of an independent state was not a guaranteed conclusion for the small Finnish nation. Recognition by Russia and other

Svinhufvud's Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917 and Parliament adopted it on 6 December. The social democrats voted against the Senate's proposal, while presenting an alternative declaration of sovereignty. The establishment of an independent state was not a guaranteed conclusion for the small Finnish nation. Recognition by Russia and other

On 12 January 1918, Parliament authorised the Svinhufvud Senate to establish internal order and discipline on behalf of the state. On 15 January,

On 12 January 1918, Parliament authorised the Svinhufvud Senate to establish internal order and discipline on behalf of the state. On 15 January,

At the beginning of the war, a discontinuous

At the beginning of the war, a discontinuous

While the conflict has been called by some, "The War of Amateurs", the White Army had two major advantages over the Red Guards: the professional military leadership of Gustaf Mannerheim and his staff, which included 84 Swedish volunteer officers and former Finnish officers of the tsar's army; and 1,450 soldiers of the 1,900-strong, Jäger battalion. The majority of the unit arrived in Vaasa on 25 February 1918., , , On the battlefield, the Jägers, battle-hardened on the Eastern Front, provided strong leadership that made disciplined combat of the common White troopers possible. The soldiers were similar to those of the Reds, having brief and inadequate training. At the beginning of the war, the White Guards' top leadership had little authority over volunteer White units, which obeyed only their local leaders. At the end of February, the Jägers started a rapid training of six conscript regiments.

The Jäger battalion was politically divided, too. Four-hundred-and-fifty –mostly socialist– Jägers remained stationed in Germany, as it was feared they were likely to side with the Reds. White Guard leaders faced a similar problem when drafting young men to the army in February 1918: 30,000 obvious supporters of the Finnish labour movement never showed up. It was also uncertain whether common troops drafted from the small-sized and poor farms of central and northern Finland had strong enough motivation to fight the Finnish Reds. The Whites' propaganda promoted the idea that they were fighting a defensive war against Bolshevist Russians, and belittled the role of the Red Finns among their enemies. Social divisions appeared both between southern and northern Finland and within rural Finland. The economy and society of the north had modernised more slowly than that of the south. There was a more pronounced conflict between

While the conflict has been called by some, "The War of Amateurs", the White Army had two major advantages over the Red Guards: the professional military leadership of Gustaf Mannerheim and his staff, which included 84 Swedish volunteer officers and former Finnish officers of the tsar's army; and 1,450 soldiers of the 1,900-strong, Jäger battalion. The majority of the unit arrived in Vaasa on 25 February 1918., , , On the battlefield, the Jägers, battle-hardened on the Eastern Front, provided strong leadership that made disciplined combat of the common White troopers possible. The soldiers were similar to those of the Reds, having brief and inadequate training. At the beginning of the war, the White Guards' top leadership had little authority over volunteer White units, which obeyed only their local leaders. At the end of February, the Jägers started a rapid training of six conscript regiments.

The Jäger battalion was politically divided, too. Four-hundred-and-fifty –mostly socialist– Jägers remained stationed in Germany, as it was feared they were likely to side with the Reds. White Guard leaders faced a similar problem when drafting young men to the army in February 1918: 30,000 obvious supporters of the Finnish labour movement never showed up. It was also uncertain whether common troops drafted from the small-sized and poor farms of central and northern Finland had strong enough motivation to fight the Finnish Reds. The Whites' propaganda promoted the idea that they were fighting a defensive war against Bolshevist Russians, and belittled the role of the Red Finns among their enemies. Social divisions appeared both between southern and northern Finland and within rural Finland. The economy and society of the north had modernised more slowly than that of the south. There was a more pronounced conflict between

In March 1918, the German Empire intervened in the Finnish Civil War on the side of the White Army. Finnish activists leaning on Germanism had been seeking German aid in freeing Finland from Soviet hegemony since late 1917, but because of the pressure they were facing at the

In March 1918, the German Empire intervened in the Finnish Civil War on the side of the White Army. Finnish activists leaning on Germanism had been seeking German aid in freeing Finland from Soviet hegemony since late 1917, but because of the pressure they were facing at the

The Battle for Tampere was fought between 16,000 White and 14,000 Red soldiers. It was Finland's first large-scale urban battle and one of the four most decisive military engagements of the war. The fight for the area of Tampere began on 28 March, on the eve of Easter 1918, later called "Bloody

The Battle for Tampere was fought between 16,000 White and 14,000 Red soldiers. It was Finland's first large-scale urban battle and one of the four most decisive military engagements of the war. The fight for the area of Tampere began on 28 March, on the eve of Easter 1918, later called "Bloody

Aamulehti

( Finnish for "morning newspaper") is a Finnish-language daily newspaper published in Tampere, Finland.

History and profile

''Aamulehti'' was founded in 1881 to "improve the position of the Finnish people and the Finnish language" during R ...

'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil War 29%, Citizen War 25%, Class War 13%, Freedom War 11%, Red Rebellion 5%, Revolution 1%, other name 2% and no answer 14%, was a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of the country between White Finland

The Whites ( fi, Valkoiset, ; sv, De vita; rus, links=1, Белофи́нны, Belofínny, bʲɪɫɐˈfʲinɨ), or White Finland, was the name used to refer to the refugee government and forces under Pehr Evind Svinhufvud's first senate who op ...

and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic

The Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (FSWR), more commonly referred to as Red Finland, was a self-proclaimed Finland, Finnish socialist state that ruled parts of the country during the Finnish Civil War of 1918. It was outlined on 29 January 1 ...

(Red Finland) during the country's transition from a grand duchy

A grand duchy is a country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was often used in th ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

to an independent state. The clashes took place in the context of the national, political, and social turmoil caused by World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

( Eastern Front) in Europe. The war was fought between the "Reds", led by a section of the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

, and the "Whites", conducted by the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

-based senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and the German Imperial Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

. The paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

Red Guards, which were composed of industrial and agrarian workers, controlled the cities and industrial centers of southern Finland. The paramilitary White Guards, which consisted of land owners and those in the middle- and upper-classes, controlled rural central and northern Finland, and were led by General C. G. E. Mannerheim.

In the years before the conflict, Finland had experienced rapid population growth, industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, pre-urbanisation and the rise of a comprehensive labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

. The country's political and governmental systems were in an unstable phase of democratisation

Democratization, or democratisation, is the transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction. It may be a hybrid regime in transition from an authoritarian regime to a full ...

and modernisation. The socio-economic condition and education of the population had gradually improved, and national thinking and cultural life had increased. World War I led to the collapse of the Russian Empire, causing a power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has r ...

in Finland, and the subsequent struggle for dominance led to militarisation and an escalating crisis between the left-leaning labour movement and the conservatives. The Reds carried out an unsuccessful general offensive in February 1918, supplied with weapons by Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. A counteroffensive by the Whites began in March, reinforced by the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

's military detachments in April. The decisive engagements were the Battles of Tampere and Vyborg

Vyborg (; rus, Вы́борг, links=1, r=Výborg, p=ˈvɨbərk; fi, Viipuri ; sv, Viborg ; german: Wiborg ) is a town in, and the administrative center of, Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus ...

, won by the Whites, and the Battles of Helsinki and Lahti

Lahti (; sv, Lahtis) is a city and municipality in Finland. It is the capital of the region of Päijänne Tavastia (Päijät-Häme) and its growing region is one of the main economic hubs of Finland. Lahti is situated on a bay at the southern e ...

, won by German troops, leading to overall victory for the Whites and the German forces. Political violence

Political violence is violence which is perpetrated in order to achieve political goals. It can include violence which is used by a state against other states ( war), violence which is used by a state against civilians and non-state actors (for ...

became a part of this warfare. Around 12,500 Red prisoners died of malnutrition and disease in camps Camps may refer to:

People

*Ramón Camps (1927–1994), Argentine general

*Gabriel Camps (1927–2002), French historian

*Luís Espinal Camps (1932–1980), Spanish missionary to Bolivia

* Victoria Camps (b. 1941), Spanish philosopher and professo ...

. About 39,000 people, of whom 36,000 were Finns, died in the conflict.

In the immediate aftermath, the Finns passed from Russian governance to the German sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

with a plan to establish a German-led Finnish monarchy

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

The culture of Finland combines indigenous heritage, as represented for example by the country's national languages Finnish (a Uralic language) an ...

. The scheme ended with Germany's defeat in World War I, and Finland instead emerged as an independent, democratic republic. The civil war divided the nation for decades. Finnish society was reunited through social compromises based on a long-term culture of moderate politics and religion and the post-war economic recovery.

The Finnish Civil War of 1918 was the second civil conflict within Finland's borders, as the Cudgel War

The Cudgel War (also Club War, fi, Nuijasota, links=no, sv, Klubbekriget, links=no) was a 1596–1597 peasant uprising in Finland, which was then part of the Kingdom of Sweden. The name of the uprising derives from the fact that the peasants ...

of 1596–1597 (where poor peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s rose up against the troops, nobles and cavalry who taxed them) had similar features.

Background

International politics

The main factor behind the Finnish Civil War was a political crisis arising out of World War I. Under the pressures of the Great War, the Russian Empire collapsed, leading to theFebruary

February is the second month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The month has 28 days in common years or 29 in leap years, with the 29th day being called the ''leap day''. It is the first of five months not to have 31 days (th ...

and October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

s in 1917. This breakdown caused a power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has r ...

and a subsequent struggle for power in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

. Grand Duchy of Finland (1809–1917), became embroiled in the turmoil. Geopolitically

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

less important than the continental Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

–Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

gateway, Finland, isolated by the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, was relatively peaceful until early 1918. The war between the German Empire and Russia had only indirect effects on the Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

. Since the end of the 19th century, the Grand Duchy had become a vital source of raw materials

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feeds ...

, industrial products, food and labour for the growing Imperial Russian capital Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(modern Saint Petersburg), and World War I emphasised that role. Strategically, the Finnish territory was the less important northern section of the Estonian–Finnish gateway and a buffer zone to and from Petrograd through the Narva

Narva, russian: Нарва is a municipality and city in Estonia. It is located in Ida-Viru county, at the eastern extreme point of Estonia, on the west bank of the Narva river which forms the Estonia–Russia international border. With 5 ...

area, the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and ...

and the Karelian Isthmus

The Karelian Isthmus (russian: Карельский перешеек, Karelsky peresheyek; fi, Karjalankannas; sv, Karelska näset) is the approximately stretch of land, situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga in northwestern ...

.

The German Empire saw Eastern Europe—primarily Russia—as a major source of vital products and raw materials, both during World War I and for the future. Her resources overstretched by the two-front war, Germany attempted to divide Russia by providing financial support to revolutionary groups, such as the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and the Socialist Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

, and to radical, separatist factions, such as the Finnish national activist movement leaning toward Germanism. Between 30 and 40 million marks were spent on this endeavour. Controlling the Finnish area would allow the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

to penetrate Petrograd and the Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula (russian: Кольский полуостров, Kolsky poluostrov; sjd, Куэлнэгк нёа̄ррк) is a peninsula in the extreme northwest of Russia, and one of the largest peninsulas of Europe. Constituting the bulk ...

, an area rich in raw materials for the mining industry. Finland possessed large ore reserves and a well-developed forest industry.

From 1809 to 1898, a period called ''Pax Russica'', the peripheral authority of the Finns gradually increased, and Russo-Finnish relations were exceptionally peaceful in comparison with other parts of the Russian Empire. Russia's defeat in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

in the 1850s led to attempts to speed up the modernisation of the country. This caused more than 50 years of economic, industrial, cultural and educational progress in the Grand Duchy of Finland, including an improvement in the status of the Finnish language. All this encouraged Finnish nationalism and cultural unity through the birth of the Fennoman movement, which bound the Finns to the domestic administration and led to the idea that the Grand Duchy was an increasingly autonomous state of the Russian Empire.

In 1899, the Russian Empire initiated a policy of integration through the Russification of Finland

The policy of Russification of Finland ( fi, sortokaudet / sortovuodet, lit=times/years of oppression; russian: Русификация Финляндии, translit=Rusyfikatsiya Finlyandii) was a governmental policy of the Russian Empire aimed at ...

. The strengthened, pan-slavist

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rul ...

central power tried to unite the "Russian Multinational Dynastic Union" as the military and strategic situation of Russia became more perilous due to the rise of Germany and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. Finns called the increased military and administrative control, "the First Period of Oppression", and for the first time Finnish politicians drew up plans for disengagement from Russia or sovereignty for Finland. In the struggle against integration, activists drawn from sections of the working class and the Swedish-speaking intelligentsia carried out terrorist acts. During World War I and the rise of Germanism, the pro-Swedish Svecomans began their covert collaboration with Imperial Germany and, from 1915 to 1917, a Jäger (; ) battalion consisting of 1,900 Finnish volunteers was trained in Germany.

Domestic politics

The major reasons for rising political tensions among Finns were the autocratic rule of the Russiantsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

and the undemocratic class system of the estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed a ...

. The latter system originated in the regime of the Swedish Empire

The Swedish Empire was a European great power that exercised territorial control over much of the Baltic region during the 17th and early 18th centuries ( sv, Stormaktstiden, "the Era of Great Power"). The beginning of the empire is usually ta ...

that preceded Russian governance and divided the Finnish people economically, socially and politically. Finland's population grew rapidly in the nineteenth century (from 860,000 in 1810 to 3,130,000 in 1917), and a class of agrarian and industrial workers, as well as crofters

A croft is a fenced or enclosed area of land, usually small and arable, and usually, but not always, with a crofter's dwelling thereon. A crofter is one who has tenure and use of the land, typically as a tenant farmer, especially in rural a ...

, emerged over the period. The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

was rapid in Finland, though it started later than in the rest of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Industrialisation was financed by the state and some of the social problems associated with the industrial process were diminished by the administration's actions. Among urban workers, socio-economic problems steepened during periods of industrial depression. The position of rural workers worsened after the end of the nineteenth century, as farming became more efficient and market-oriented, and the development of industry was insufficiently vigorous to fully utilise the rapid population growth of the countryside.

The difference between Scandinavian-Finnish and Russian- Slavic culture affected the nature of Finnish national integration. The upper social strata took the lead and gained domestic authority from the Russian tsar in 1809. The estates planned to build an increasingly autonomous Finnish state, led by the elite and the intelligentsia. The Fennoman movement aimed to include the common people in a non-political role; the labour movement, youth associations and the temperance movement were initially led "from above".

Between 1870 and 1916 industrialisation gradually improved social conditions and the self-confidence of workers, but while the standard of living of the common people rose in absolute terms, the rift between rich and poor deepened markedly. The commoners' rising awareness of socio-economic and political questions interacted with the ideas of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

, social liberalism

Social liberalism (german: Sozialliberalismus, es, socioliberalismo, nl, Sociaalliberalisme), also known as new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism, or simply liberalism in the contemporary United States, left-liberalism ...

and nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

. The workers' initiatives and the corresponding responses of the dominant authorities intensified social conflict in Finland. The Finnish labour movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from

The Finnish labour movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

, religious movements

Various sociological classifications of religious movements have been proposed by scholars. In the sociology of religion, the most widely used classification is the church-sect typology. The typology is differently construed by different sociolog ...

and Fennomania, had a Finnish nationalist, working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

character. From 1899 to 1906, the movement became conclusively independent, shedding the paternalistic thinking of the Fennoman estates, and it was represented by the Finnish Social Democratic Party, established in 1899. Workers' activism was directed both toward opposing Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cult ...

and in developing a domestic policy that tackled social problems and responded to the demand for democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

. This was a reaction to the domestic dispute, ongoing since the 1880s, between the Finnish nobility-bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

and the labour movement concerning voting rights for the common people. Despite their obligations as obedient, peaceful and non-political inhabitants of the Grand Duchy (who had, only a few decades earlier itation needed accepted the class system as the natural order of their life), the commoners began to demand their civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

and citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

in Finnish society. itation neededThe power struggle between the Finnish estates and the Russian administration gave a concrete role model and free space for the labour movement. On the other side, due to an at-least century-long tradition and experience of administrative authority, the Finnish elite saw itself as the inherent natural leader of the nation. The political struggle for democracy was solved outside Finland, in international politics: the Russian Empire's failed 1904–1905 war against Japan led to the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

in Russia and to a general strike in Finland. In an attempt to quell the general unrest, the system of estates was abolished in the Parliamentary Reform of 1906. The general strike increased support for the social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

substantially. The party encompassed a higher proportion of the population than any other socialist movement in the world.

The Reform of 1906 was a giant leap towards the political and social liberalisation of the common Finnish people because the Russian House of Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastacia of Russia, Anastasi ...

had been the most autocratic and conservative ruler in Europe. The Finns adopted a unicameral parliamentary system, the Parliament of Finland

The Parliament of Finland ( ; ) is the unicameral and supreme legislature of Finland, founded on 9 May 1906. In accordance with the Constitution of Finland, sovereignty belongs to the people, and that power is vested in the Parliament. The ...

(; ) with universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

. The number of voters increased from 126,000 to 1,273,000, including female citizens. The reform led to the social democrats obtaining about fifty percent of the popular vote, but the Tsar regained his authority after the crisis of 1905. Subsequently, during the more severe programme of Russification, called "the Second Period of Oppression" by the Finns, the Tsar neutralised the power of the Finnish Parliament between 1908 and 1917. He dissolved the assembly, ordered parliamentary elections almost annually, and determined the composition of the Finnish Senate, which did not correlate with the Parliament.

The capacity of the Finnish Parliament to solve socio-economic problems was stymied by confrontations between the largely uneducated commoners and the former estates. Another conflict festered as employers denied collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The ...

and the right of the labour unions to represent workers. The parliamentary process disappointed the labour movement, but as dominance in the Parliament and legislation was the workers' most likely way to obtain a more balanced society, they identified themselves with the state. Overall domestic politics led to a contest for leadership of the Finnish state during the ten years before the collapse of the Russian Empire.

February Revolution

Build-up

The Second Period of Russification was halted on 15 March 1917 by the February Revolution, which removed the tsar,

The Second Period of Russification was halted on 15 March 1917 by the February Revolution, which removed the tsar, Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

. The collapse of Russia was caused by military defeats, war-weariness against the duration and hardships of the Great War, and the collision between the most conservative regime in Europe and a Russian people desiring modernisation. The Tsar's power was transferred to the State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper hous ...

(Russian Parliament) and the right-wing Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

, but this new authority was challenged by the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

(city council), leading to dual power in the country.

The autonomous status of 1809–1899 was returned to the Finns by the March 1917 manifesto of the Russian Provisional Government. For the first time in history, ''de facto'' political power existed in the Parliament of Finland. The political left, consisting mainly of social democrats, covered a wide spectrum from moderate to revolutionary socialists. The political right was even more diverse, ranging from social liberals and moderate conservatives to rightist conservative elements. The four main parties were:

* The conservative Finnish Party;

* the Young Finnish Party

The Young Finnish Party or Constitutional-Fennoman Party ( fi, Nuorsuomalainen Puolue or ) was a liberal and nationalist political party in the Grand Duchy of Finland. It began as an upper-class reformist movement during the 1870s and formed as a ...

, which included both liberals and conservatives, with the liberals divided between social liberals and economic liberals

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism, ...

;

* the social reformist, centrist Agrarian League, which drew its support mainly from peasants with small or mid-sized farms; and

* the conservative Swedish People's Party

The Swedish People's Party of Finland ( sv, Svenska folkpartiet i Finland (SFP); fi, Suomen ruotsalainen kansanpuolue (RKP)) is a political party in Finland aiming to represent the interests of the minority Swedish-speaking population of Finlan ...

, which sought to retain the rights of the former nobility and the Swedish-speaking minority of Finland.

During 1917, a power struggle and social disintegration interacted. The collapse of Russia induced a chain reaction of disintegration, starting from the government, military and economy, and spreading to all fields of society, such as local administration, workplaces and to individual citizens. The social democrats wanted to retain the civil rights already achieved and to increase the socialists' power over society. The conservatives feared the loss of their long-held socio-economic dominance. Both factions collaborated with their equivalents in Russia, deepening the split in the nation.

The Social Democratic Party gained an absolute majority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority r ...

in the parliamentary elections of 1916. A new Senate was formed in March 1917 by Oskari Tokoi, but it did not reflect the socialists' large parliamentary majority: it comprised six social democrats and six non-socialists. In theory, the Senate consisted of a broad national coalition, but in practice (with the main political groups unwilling to compromise

To compromise is to make a deal between different parties where each party gives up part of their demand. In arguments, compromise is a concept of finding agreement through communication, through a mutual acceptance of terms—often involving va ...

and top politicians remaining outside of it), it proved unable to solve any major Finnish problem. After the February Revolution, political authority descended to the street level: mass meetings, strike organisations and worker-soldier councils on the left and to active organisations of employers on the right, all serving to undermine the authority of the state.

The February Revolution halted the Finnish economic boom caused by the Russian war-economy. The collapse in business led to unemployment and high inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

, but the employed workers gained an opportunity to resolve workplace problems. The commoners' call for the eight-hour working day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

, better working conditions and higher wages led to demonstrations and large-scale strikes in industry and agriculture.

While the Finns had specialised in milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digest solid food. Immune factors and immune-modulat ...

and butter

Butter is a dairy product made from the fat and protein components of churned cream. It is a semi-solid emulsion at room temperature, consisting of approximately 80% butterfat. It is used at room temperature as a spread, melted as a condim ...

production, the bulk of the food supply for the country depended on cereals produced in southern Russia. The cessation of cereal imports from disintegrating Russia led to food shortages in Finland. The Senate responded by introducing rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

and price controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of good ...

. The farmers resisted the state control and thus a black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the ...

, accompanied by sharply rising food prices, formed. As a consequence, export to the free market of the Petrograd area increased. Food supply, prices and, in the end, the fear of starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

became emotional political issues between farmers and urban workers, especially those who were unemployed. Common people, their fears exploited by politicians and an incendiary, polarised political media, took to the streets. Despite the food shortages, no actual large-scale starvation hit southern Finland before the civil war and the food market remained a secondary stimulator in the power struggle of the Finnish state.

Contest for leadership

The passing of the Tokoi Senate bill called the "Law of Supreme Power" (, more commonly known as ''valtalaki''; ) in July 1917, triggered one of the key crises in the power struggle between the social democrats and the conservatives. The fall of the Russian Empire opened the question of who would hold sovereign political authority in the former Grand Duchy. After decades of political disappointment, the February Revolution offered the Finnish social democrats an opportunity to govern; they held the absolute majority in Parliament. The conservatives were alarmed by the continuous increase of the socialists' influence since 1899, which reached a climax in 1917.

The "Law of Supreme Power" incorporated a plan by the socialists to substantially increase the authority of Parliament, as a reaction to the non-parliamentary and conservative leadership of the Finnish Senate between 1906 and 1916. The bill furthered Finnish autonomy in domestic affairs: the Russian Provisional Government was only allowed the right to control Finnish foreign and military policies. The Act was adopted with the support of the Social Democratic Party, the Agrarian League, part of the Young Finnish Party and some activists eager for Finnish sovereignty. The conservatives opposed the bill and some of the most right-wing representatives resigned from Parliament.

In Petrograd, the social democrats' plan had the backing of the Bolsheviks. They had been plotting a revolt against the Provisional Government since April 1917, and pro-Soviet demonstrations during the

The passing of the Tokoi Senate bill called the "Law of Supreme Power" (, more commonly known as ''valtalaki''; ) in July 1917, triggered one of the key crises in the power struggle between the social democrats and the conservatives. The fall of the Russian Empire opened the question of who would hold sovereign political authority in the former Grand Duchy. After decades of political disappointment, the February Revolution offered the Finnish social democrats an opportunity to govern; they held the absolute majority in Parliament. The conservatives were alarmed by the continuous increase of the socialists' influence since 1899, which reached a climax in 1917.

The "Law of Supreme Power" incorporated a plan by the socialists to substantially increase the authority of Parliament, as a reaction to the non-parliamentary and conservative leadership of the Finnish Senate between 1906 and 1916. The bill furthered Finnish autonomy in domestic affairs: the Russian Provisional Government was only allowed the right to control Finnish foreign and military policies. The Act was adopted with the support of the Social Democratic Party, the Agrarian League, part of the Young Finnish Party and some activists eager for Finnish sovereignty. The conservatives opposed the bill and some of the most right-wing representatives resigned from Parliament.

In Petrograd, the social democrats' plan had the backing of the Bolsheviks. They had been plotting a revolt against the Provisional Government since April 1917, and pro-Soviet demonstrations during the July Days

The July Days (russian: Июльские дни) were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between . It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisi ...

brought matters to a head. The Helsinki Soviet and the Regional Committee of the Finnish Soviets, led by the Bolshevik Ivar Smilga, both pledged to defend the Finnish Parliament, were it threatened with attack. However, the Provisional Government still had sufficient support in the Russian army to survive and as the street movement waned, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

fled to Karelia. In the aftermath of these events, the "Law of Supreme Power" was overruled and the social democrats eventually backed down; more Russian troops were sent to Finland and, with the co-operation and insistence of the Finnish conservatives, Parliament was dissolved and new elections announced.

In the October 1917 elections, the social democrats lost their absolute majority, which radicalised the labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

and decreased support for moderate politics. The crisis of July 1917 did not bring about the Red Revolution of January 1918 on its own, but together with political developments based on the commoners' interpretation of the ideas of Fennomania and socialism, the events favoured a Finnish revolution. In order to win power, the socialists had to overcome Parliament.

The February Revolution resulted in a loss of institutional authority in Finland and the dissolution of the police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

force, creating fear and uncertainty. In response, both the right and left assembled their own security groups, which were initially local and largely unarmed. By late 1917, following the dissolution of Parliament, in the absence of a strong government and national armed forces, the security groups began assuming a broader and more paramilitary character. The Civil Guards (; ; ) and the later White Guards (; ) were organised by local men of influence: conservative academics, industrialists, major landowners, and activists. The Workers' Order Guards (; ) and the Red Guards (; ) were recruited through the local social democratic party sections and from the labour unions.

October Revolution

The Bolsheviks' and Vladimir Lenin's October Revolution of 7 November 1917 transferred political power in Petrograd to the radical, left-wing socialists. The German government's decision to arrange safe-conduct for Lenin and his comrades from exile in Switzerland to Petrograd in April 1917, was a success. An armistice between Germany and the Bolshevik regime came into force on 6 December and peace negotiations began on 22 December 1917 atBrest-Litovsk

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

.

November 1917 became another watershed in the 1917–1918 rivalry for the leadership of Finland. After the dissolution of the Finnish Parliament, polarisation between the social democrats and the conservatives increased markedly and the period witnessed the appearance of political violence. An agricultural worker was shot during a local strike on 9 August 1917 at Ypäjä

Ypäjä is a municipality located in the countryside of South-Western Finland. It belongs to the province of Southern Finland and the region of Tavastia Proper. The municipality has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. T ...

and a Civil Guard member was killed in a local political crisis at Malmi on 24 September. The October Revolution disrupted the informal truce between the Finnish non-socialists and the Russian Provisional Government. After political wrangling over how to react to the revolt, the majority of the politicians accepted a compromise proposal by Santeri Alkio, the leader of the Agrarian League. Parliament seized the sovereign power in Finland on 15 November 1917 based on the socialists' "Law of Supreme Power" and ratified their proposals of an eight-hour working day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

and universal suffrage in local election

In many parts of the world, local elections take place to select office-holders in local government, such as mayors and councillors. Elections to positions within a city or town are often known as "municipal elections". Their form and conduct vary ...

s, from July 1917.

The purely non-socialist, conservative-led government of Pehr Evind Svinhufvud

Pehr Evind Svinhufvud af Qvalstad (; 15 December 1861 – 29 February 1944) was the third president of Finland from 1931 to 1937. Serving as a lawyer, judge, and politician in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland, he played a major role in the ...

was appointed on 27 November. This nomination was both a long-term aim of the conservatives and a response to the challenges of the labour movement during November 1917. Svinhufvud's main aspirations were to separate Finland from Russia, to strengthen the Civil Guards, and to return a part of Parliament's new authority to the Senate. There were 149 Civil Guards on 31 August 1917 in Finland, counting local units and subsidiary White Guards in towns and rural communes; 251 on 30 September; 315 on 31 October; 380 on 30 November and 408 on 26 January 1918. The first attempt at serious military training among the Guards was the establishment of a 200-strong cavalry school at the Saksanniemi estate in the vicinity of the town of Porvoo

Porvoo (; sv, Borgå ; la, Borgoa) is a city and a municipality in the Uusimaa region of Finland, situated on the southern coast about east of the city border of Helsinki and about from the city centre. Porvoo was one of the six medieva ...

, in September 1917. The vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives f ...

of the Finnish Jägers and German weaponry arrived in Finland during October–November 1917 on the ' freighter and the German U-boat '; around 50 Jägers had returned by the end of 1917.

After political defeats in July and October 1917, the social democrats put forward an uncompromising program called "We Demand" (; ) on 1 November, in order to push for political concessions. They insisted upon a return to the political status before the dissolution of Parliament in July 1917, disbandment of the Civil Guards and elections to establish a Finnish Constituent Assembly. The program failed and the socialists initiated a general strike during 14–19 November to increase political pressure on the conservatives, who had opposed the "Law of Supreme Power" and the parliamentary proclamation of sovereign power on 15 November.

Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

became the goal of the radicalised socialists after the loss of political control, and events in November 1917 offered momentum for a socialist uprising. In this phase, Lenin and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, under threat in Petrograd, urged the social democrats to take power in Finland. The majority of Finnish socialists were moderate and preferred parliamentary methods, prompting the Bolsheviks to label them "reluctant revolutionaries". The reluctance diminished as the general strike appeared to offer a major channel of influence for the workers in southern Finland. The strike leadership voted by a narrow majority to start a revolution on 16 November, but the uprising had to be called off the same day due to the lack of active revolutionaries to execute it.

At the end of November 1917, the moderate socialists among the social democrats won a second vote over the radicals in a debate over revolutionary versus parliamentary means, but when they tried to pass a resolution to completely abandon the idea of a socialist revolution, the party representatives and several influential leaders voted it down. The Finnish labour movement wanted to sustain a military force of its own and to keep the revolutionary road open, too. The wavering Finnish socialists disappointed V. I. Lenin and in turn, he began to encourage the Finnish Bolsheviks in Petrograd.

Among the labour movement, a more marked consequence of the events of 1917 was the rise of the Workers' Order Guards. There were 20–60 separate guards between 31 August and 30 September 1917, but on 20 October, after defeat in parliamentary elections, the Finnish labour movement proclaimed the need to establish more worker units. The announcement led to a rush of recruits: on 31 October the number of guards was 100–150; 342 on 30 November 1917 and 375 on 26 January 1918. Since May 1917, the paramilitary organisations of the left had grown in two phases, the majority of them as Workers' Order Guards. The minority were Red Guards, these were partly underground groups formed in industrialised towns and industrial centres, such as

At the end of November 1917, the moderate socialists among the social democrats won a second vote over the radicals in a debate over revolutionary versus parliamentary means, but when they tried to pass a resolution to completely abandon the idea of a socialist revolution, the party representatives and several influential leaders voted it down. The Finnish labour movement wanted to sustain a military force of its own and to keep the revolutionary road open, too. The wavering Finnish socialists disappointed V. I. Lenin and in turn, he began to encourage the Finnish Bolsheviks in Petrograd.

Among the labour movement, a more marked consequence of the events of 1917 was the rise of the Workers' Order Guards. There were 20–60 separate guards between 31 August and 30 September 1917, but on 20 October, after defeat in parliamentary elections, the Finnish labour movement proclaimed the need to establish more worker units. The announcement led to a rush of recruits: on 31 October the number of guards was 100–150; 342 on 30 November 1917 and 375 on 26 January 1918. Since May 1917, the paramilitary organisations of the left had grown in two phases, the majority of them as Workers' Order Guards. The minority were Red Guards, these were partly underground groups formed in industrialised towns and industrial centres, such as Helsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the Capital city, capital, primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Finland, most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of U ...

, Kotka

Kotka (; ; la, Aquilopolis) is a city in the southern part of the Kymenlaakso province on the Gulf of Finland. Kotka is a major port and industrial city and also a diverse school and cultural city, which was formerly part of the old Kymi parish ...

and Tampere, based on the original Red Guards that had been formed during 1905–1906 in Finland.

The presence of the two opposing armed forces created a state of dual power and divided sovereignty on Finnish society. The decisive rift between the guards broke out during the general strike: the Reds executed several political opponents in southern Finland and the first armed clashes between the Whites and Reds took place. In total, 34 casualties were reported. Eventually, the political rivalries of 1917 led to an arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

and an escalation towards civil war.

Independence of Finland

The disintegration of Russia offered Finns a historic opportunity to gain national independence. After the October Revolution, the conservatives were eager for secession from Russia in order to control the left and minimise the influence of the Bolsheviks. The socialists were skeptical about sovereignty under conservative rule, but they feared a loss of support among nationalistic workers, particularly after having promised increased national liberty through the "Law of Supreme Power". Eventually, both political factions supported an independent Finland, despite strong disagreement over the composition of the nation's leadership.

Nationalism had become a "civic religion" in Finland by the end of nineteenth century, but the goal during the general strike of 1905 was a return to the autonomy of 1809–1898, not full independence. In comparison to the unitary Swedish regime, the domestic power of Finns had increased under the less uniform Russian rule. Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the

The disintegration of Russia offered Finns a historic opportunity to gain national independence. After the October Revolution, the conservatives were eager for secession from Russia in order to control the left and minimise the influence of the Bolsheviks. The socialists were skeptical about sovereignty under conservative rule, but they feared a loss of support among nationalistic workers, particularly after having promised increased national liberty through the "Law of Supreme Power". Eventually, both political factions supported an independent Finland, despite strong disagreement over the composition of the nation's leadership.

Nationalism had become a "civic religion" in Finland by the end of nineteenth century, but the goal during the general strike of 1905 was a return to the autonomy of 1809–1898, not full independence. In comparison to the unitary Swedish regime, the domestic power of Finns had increased under the less uniform Russian rule. Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the markka

The markka ( fi, markka; sv, mark; sign: Mk; ISO code: FIM, typically known outside Finland as the Finnish mark) was the currency of Finland from 1860 until 28 February 2002, when it ceased to be legal tender. The mark was divided into 100 p ...

(deployed 1860), and customs organisation and the industrial progress of 1860–1916. The economy was dependent on the huge Russian market and separation would disrupt the profitable Finnish financial zone. The economic collapse of Russia and the power struggle of the Finnish state in 1917 were among the key factors that brought sovereignty to the fore in Finland.

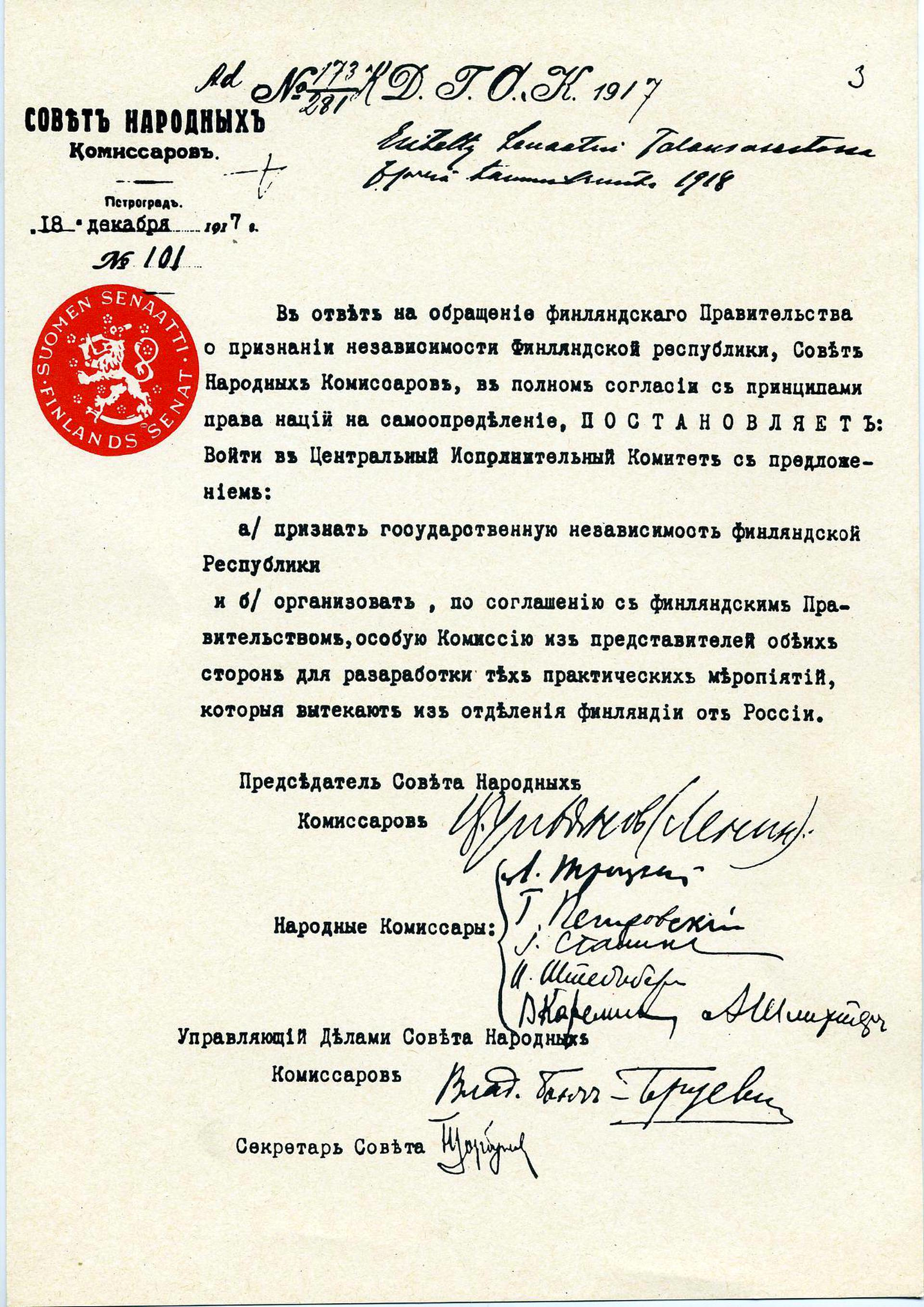

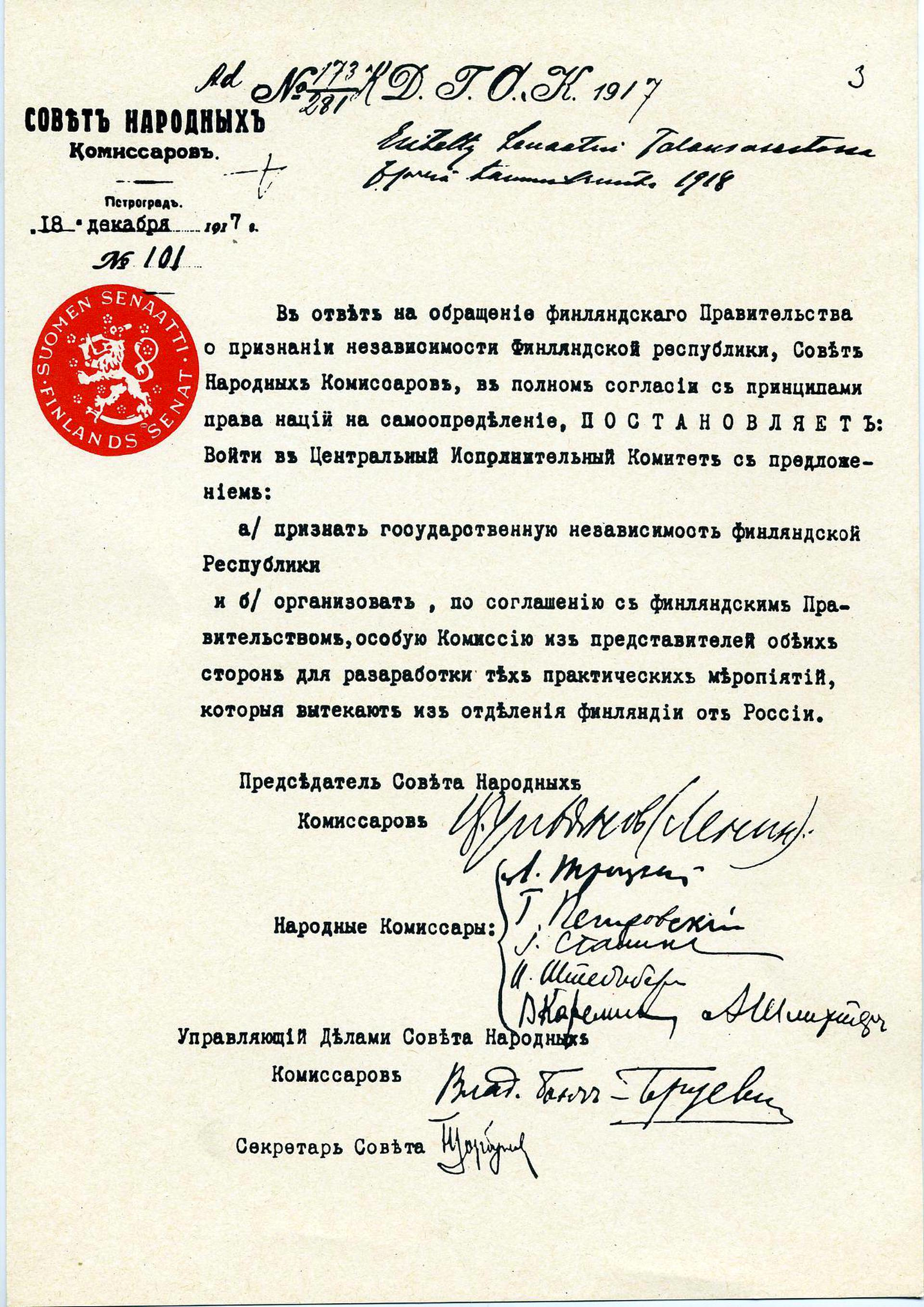

Svinhufvud's Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917 and Parliament adopted it on 6 December. The social democrats voted against the Senate's proposal, while presenting an alternative declaration of sovereignty. The establishment of an independent state was not a guaranteed conclusion for the small Finnish nation. Recognition by Russia and other

Svinhufvud's Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917 and Parliament adopted it on 6 December. The social democrats voted against the Senate's proposal, while presenting an alternative declaration of sovereignty. The establishment of an independent state was not a guaranteed conclusion for the small Finnish nation. Recognition by Russia and other great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

s was essential; Svinhufvud accepted that he had to negotiate with Lenin for the acknowledgement. The socialists, having been reluctant to enter talks with the Russian leadership in July 1917, sent two delegations to Petrograd to request that Lenin approve Finnish sovereignty.

In December 1917, Lenin was under intense pressure from the Germans to conclude peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, and the Bolsheviks' rule was in crisis, with an inexperienced administration and the demoralised army facing powerful political and military opponents. Lenin calculated that the Bolsheviks could fight for central parts of Russia but had to give up some peripheral territories, including Finland in the geopolitically less important north-western corner. As a result, Svinhufvud's delegation won Lenin's concession of sovereignty on 31 December 1917.

By the beginning of the Civil War, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland had recognised Finnish independence. The United Kingdom and United States did not approve it; they waited and monitored the relations between Finland and Germany (the main enemy of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

), hoping to override Lenin's regime and to get Russia back into the war against the German Empire. In turn, the Germans hastened Finland's separation from Russia so as to move the country to within their sphere of influence.

Warfare

Escalation

The final escalation towards war began in early January 1918, as each military or political action of the Reds or the Whites resulted in a corresponding counteraction by the other. Both sides justified their activities as defensive measures, particularly to their own supporters. On the left, the vanguard of the movement was the urban Red Guards fromHelsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the Capital city, capital, primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Finland, most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of U ...

, Kotka

Kotka (; ; la, Aquilopolis) is a city in the southern part of the Kymenlaakso province on the Gulf of Finland. Kotka is a major port and industrial city and also a diverse school and cultural city, which was formerly part of the old Kymi parish ...

and Turku

Turku ( ; ; sv, Åbo, ) is a city and former capital on the southwest coast of Finland at the mouth of the Aura River, in the region of Finland Proper (''Varsinais-Suomi'') and the former Turku and Pori Province (''Turun ja Porin lääni''; ...

; they led the rural Reds and convinced the socialist leaders who wavered between peace and war to support the revolution. On the right, the vanguard was the Jägers, who had transferred to Finland, and the volunteer Civil Guards of southwestern Finland, southern Ostrobothnia and Vyborg province in the southeastern corner of Finland. The first local battles were fought during 9–21 January 1918 in southern and southeastern Finland, mainly to win the arms race and to control Vyborg

Vyborg (; rus, Вы́борг, links=1, r=Výborg, p=ˈvɨbərk; fi, Viipuri ; sv, Viborg ; german: Wiborg ) is a town in, and the administrative center of, Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus ...

(; ).

On 12 January 1918, Parliament authorised the Svinhufvud Senate to establish internal order and discipline on behalf of the state. On 15 January,

On 12 January 1918, Parliament authorised the Svinhufvud Senate to establish internal order and discipline on behalf of the state. On 15 January, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as c ...

, a former Finnish general of the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

, was appointed the commander-in-chief of the Civil Guards. The Senate appointed the Guards, henceforth called the White Guards, as the White Army of Finland. Mannerheim placed his Headquarters of the White Army in the Vaasa