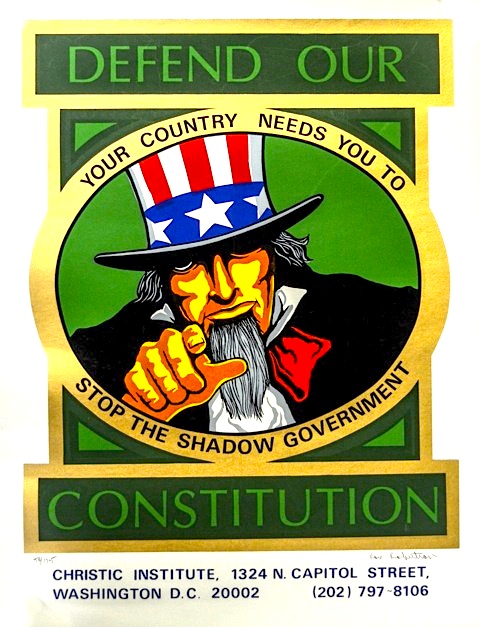

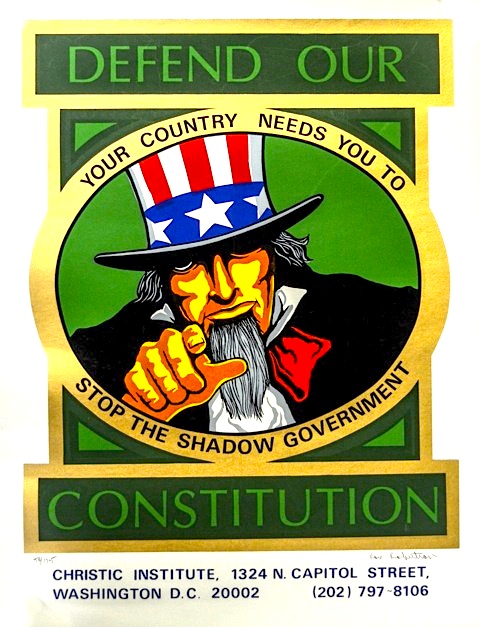

Christic Institute on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Christic Institute was a public interest

Public Eye website

/ref> The Christic Institute was succeeded by the

Official website"The Law and the Prophet"

FBI file on the Christic Institute

{{Authority control Iran–Contra affair Law firms based in Washington, D.C. Law firms established in 1980

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

firm founded in 1980 by Daniel Sheehan, his wife Sara Nelson, and their partner, William J. Davis, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

priest, after the successful conclusion of their work on the ''Silkwood'' case. Based on the ecumenical teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

, and on the lessons they learned from their experience in the Silkwood fight, the Christic Institute combined investigation, litigation, education and organizing into a unique model for social reform in the United States. In 1992 the firm lost its non-profit status after having a federal case dismissed by the court in 1988 and being penalized for filing a "frivolous lawsuit". The IRS said that the Christic Institute had acted for political reasons. The case was related to journalists injured in relation to the Iran–Contra Affair

The Iran–Contra affair ( fa, ماجرای ایران-کنترا, es, Caso Irán–Contra), often referred to as the Iran–Contra scandal, the McFarlane affair (in Iran), or simply Iran–Contra, was a political scandal in the United States ...

. The group was succeeded by a new firm, the Romero Institute

The Romero Institute is a nonprofit law and public policy center in Santa Cruz, California. The institute has two main projects: the Lakota People's Law Project based in part in the Dakotas, and Greenpower, based in California.

History Beginning ...

.

Christic notably represented victims of the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island; they prosecuted KKK

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cath ...

and American Nazi Party

The American Nazi Party (ANP) is an American far-right and neo-Nazi political party founded by George Lincoln Rockwell and headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. The organization was originally named the World Union of Free Enterprise Nation ...

members for killing Communist Workers Party demonstrators in the 1979 Greensboro Massacre

The Greensboro massacre was a deadly confrontation which occurred on November 3, 1979, in Greensboro, North Carolina, US, when members of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party (ANP) shot and killed five participants in a "Death to the Kla ...

, as well as police and federal agents who they said had known about potential violence and had not adequately protected the victims; and they defended Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

workers providing sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees (American Sanctuary Movement). Its headquarters were in Washington, D.C., with offices in several other major United States cities. The Institute received funding from a nationwide network of grassroots donors, as well as organizations like the New World Foundation The New World Foundation is a liberal foundation, based in New York. It supports organizations that work on behalf of civil rights and that seek to encourage participation of citizens in American democracy. It was founded in 1954 by Anita McCormic ...

.

Writing for the ''Columbia Journalism Review'', Chip Berlet

John Foster "Chip" Berlet (; born November 22, 1949) is an American investigative journalist, research analyst, photojournalist, scholar, and activist specializing in the study of extreme right-wing movements in the United States. He also stu ...

described the Christic Institute as "something of a rarity among advocacy groups: starting out on the left of the political spectrum, over the years it was drawn into the conspiracy theories woven by the radical right."

Three Mile Island, Greensboro Massacre, American Sanctuary Movement

In 1979, Daniel Sheehan, Sara Nelson and many of the allies and architects of the Silkwood case gathered in Washington, D.C. to found The Christic Institute. Over the next 12 years, as General Counsel for the Institute, Sheehan helped prosecute some of the most celebrated public interest cases of the time. Christic represented victims of the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island. They conducted a civil suit, seeking damages fromKKK

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cath ...

and American Nazi Party

The American Nazi Party (ANP) is an American far-right and neo-Nazi political party founded by George Lincoln Rockwell and headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. The organization was originally named the World Union of Free Enterprise Nation ...

(ANP) members for the murder of five civil rights demonstrators in the Greensboro Massacre

The Greensboro massacre was a deadly confrontation which occurred on November 3, 1979, in Greensboro, North Carolina, US, when members of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party (ANP) shot and killed five participants in a "Death to the Kla ...

. In addition, they charged the city, certain police and four Federal agents with having known of the potential for violence and failing to protect the protesters. The jury awarded damages to the plaintiffs against the city, the police department, and the KKK and ANP.

The Institute defended Catholic workers providing sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees in the American Sanctuary Movement.

The graphic novel

A graphic novel is a long-form, fictional work of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comic scholars and industry ...

''Brought to Light

''Brought to Light: Thirty Years of Drug Smuggling, Arms Deals, and Covert Action'' is an anthology of two political graphic novels, published originally by Eclipse Comics in 1988.

The two stories are ''Shadowplay: The Secret Team'' by Alan Moor ...

,'' by writers Alan Moore

Alan Moore (born 18 November 1953) is an English author known primarily for his work in comic books including '' Watchmen'', ''V for Vendetta'', '' The Ballad of Halo Jones'', ''Swamp Thing'', ''Batman:'' ''The Killing Joke'', and '' From He ...

and Joyce Brabner, used material from lawsuits filed by the Christic Institute.

''Avirgan v. Hull''

In 1986, the Christic Institute filed a $24 million civil suit on behalf of journalistsTony Avirgan and Martha Honey

Tony Avirgan and Martha Honey are a married couple and former journalistic duo who reported on the 1979 Uganda–Tanzania War and Central America in the 1980s. They were unsuccessful plaintiffs in '' Avirgan v. Hull'' (1986), a civil suit alleging ...

stating that various individuals were part of a conspiracy responsible for the La Penca bombing The La Penca bombing was a bomb attack carried out in May 30, 1984 at the remote outpost of La Penca, on the Nicaraguan side of the border with Costa Rica, along the San Juan River. It occurred during a press conference convened and conducted by ...

that injured Avirgan. The suit charged the defendants of illegally participating in assassinations, as well as arms and drug trafficking. Among the 30 defendants named were Iran–Contra figures John K. Singlaub

Major General John Kirk Singlaub (July 10, 1921 – January 29, 2022) was a major general in the United States Army, founding member of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and a highly decorated officer in the former Office of Strategic Servi ...

, Richard V. Secord

Major General Richard Vernon Secord, Retired (born July 6, 1932), is a United States Air Force officer with a notable career in covert operations. Early in his military service, he was a member of the first U.S. aviation detachment sent to the ...

, Albert Hakim Albert A. Hakim (July 16, 1936 - April 25, 2003) was an Iranian-American businessman and a figure in the Iran-Contra affair.

Born into a Jewish Iranian family, Hakim attended California Polytechnic Institute for three years, beginning in 1955. Ba ...

, and Robert W. Owen; Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

officials Thomas Clines

Thomas Gregory Clines (August 18, 1928 – July 30, 2013) was a Central Intelligence Agency covert operations officer who was a prominent figure in the Iran-Contra Affair.

Background

Clines served in the 1950–1953 Korean War, and was awarded th ...

and Theodore Shackley

Theodore George "Ted" Shackley, Jr. (July 16, 1927 – December 9, 2002) was an American CIA officer involved in many important and controversial CIA operations during the 1960s and 1970s. He is one of the most decorated CIA officers. Due to his ...

; Contra leader Adolfo Calero

Adolfo Calero Portocarrero (December 22, 1931 – June 2, 2012) was a Nicaraguan businessman and the leader of the Nicaraguan Democratic Force, the largest rebel group of the Contras, opposing the Sandinista government.

Calero was responsi ...

; Medellin cartel leaders Pablo Escobar Gaviria

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (; ; 1 December 19492 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist who was the founder and sole leader of the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed "the king of cocaine", Escobar is the wealthiest criminal in ...

and Jorge Ochoa Vasquez

Jorge Luis Ochoa Vásquez (born 30 September 1950) is a Colombian former drug trafficker who was one of the founding members of the notorious Medellín Cartel in the late 1970s. The cartel's key members were Pablo Escobar, Carlos Lehder, José ...

; Costa Rican rancher John Hull; and former mercenary Sam N. Hall.

On June 23, 1988, United States federal judge

In the United States, federal judges are judges who serve on courts established under Article Three of the U.S. Constitution. They include the chief justice and the associate justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, the circuit judges of the U.S ...

James Lawrence King

James Lawrence King (born December 20, 1927) is a Senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, and one of the longest serving federal judges in the United States.

Education and care ...

of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida

The United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida (in case citations, S.D. Fla. or S.D. Fl.) is the federal United States district court with territorial jurisdiction over the southern part of the state of Florida..

Appeals ...

dismissed the case stating: "The plaintiffs have made no showing of existence of genuine issues of material fact with respect to either the bombing at La Penca, the threats made to their news sources or threats made to themselves." According to ''The New York Times'', the case was dismissed by King at least in part due to "the fact that the vast majority of the 79 witnesses Mr. Sheehan cites as authorities were either dead, unwilling to testify, fountains of contradictory information or at best one person removed from the facts they were describing." On February 3, 1989, King ordered the Christic Institute to pay $955,000 in attorney's fees

Attorney's fee is a chiefly United States term for compensation for legal services performed by an attorney ( lawyer or law firm) for a client, in or out of court. It may be an hourly, flat-rate or contingent fee. Recent studies suggest that whe ...

and $79,500 in court costs

Court costs (also called law costs in English procedure) are the costs of handling a case, which, depending on legal rules, may or may not include the costs of the various parties in a lawsuit in addition to the costs of the court itself. In the ...

. The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit (in case citations, 11th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the following U.S. district courts:

* Middle District of Alabama

* Northern District of Alabama

* ...

affirmed the ruling, and the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

let the judgment stand by refusing to hear an additional appeal. The fine was levied in accordance with “Rule 11” of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which says that lawyers can be penalized for frivolous lawsuits.

On November 16 and 17, 1990, Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen (born September 23, 1949) is an American singer and songwriter. He has released 21 studio albums, most of which feature his backing band, the E Street Band. Originally from the Jersey Shore, he is an originato ...

, Bonnie Raitt

Bonnie Lynn Raitt (; born November 8, 1949) is an American blues singer and guitarist. In 1971, Raitt released her self-titled debut album. Following this, she released a series of critically acclaimed roots-influenced albums that incorporated ...

, and Jackson Browne

Clyde Jackson Browne (born October 9, 1948) is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and political activist who has sold over 18 million albums in the United States.

Emerging as a precocious teenage songwriter in mid-1960s Los Angeles, he h ...

performed a benefit concert for the Christic Institute at the Shrine Auditorium

The Shrine Auditorium is a landmark large-event venue in Los Angeles, California. It is also the headquarters of the Al Malaikah Temple, a division of the Shriners. It was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (No. 139) in 1975, and ...

while the case was on appeal before the Eleventh Circuit.

In the wake of the dismissal, Christic attorneys and Honey and Avirgan traded accusations over who was to blame for the failure of the case. Avirgan complained that Sheehan had handled matters poorly by chasing unsubstantiated "wild allegations" and conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

, rather than paying attention to core factual issues./ref> The Christic Institute was succeeded by the

Romero Institute

The Romero Institute is a nonprofit law and public policy center in Santa Cruz, California. The institute has two main projects: the Lakota People's Law Project based in part in the Dakotas, and Greenpower, based in California.

History Beginning ...

.

Publications

*Brought To Light

''Brought to Light: Thirty Years of Drug Smuggling, Arms Deals, and Covert Action'' is an anthology of two political graphic novels, published originally by Eclipse Comics in 1988.

The two stories are ''Shadowplay: The Secret Team'' by Alan Moor ...

: Flashpoint - The La Penca Bombing. Introduction by Jonathan V. Marshall.

Notes

External links

Official website

James Traub

James Traub (born 1954) is an American journalist. He is a contributing writer for ''The New York Times Magazine'', where he has worked since 1998. From 1994 to 1997, he was a staff writer for ''The New Yorker''. He has also written for ''The New Y ...

, '' Mother Jones'', February–March 1988. (Archived at Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

.)FBI file on the Christic Institute

{{Authority control Iran–Contra affair Law firms based in Washington, D.C. Law firms established in 1980