Christianity in the 19th century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Characteristic of Christianity in the 19th century were

Historian

Historian

excerpt

/ref> Significant names include

After 1870 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck would not tolerate any base of power outside Germany—in Rome—having a say in German affairs. He launched a Kulturkampf ("culture war") against the power of the pope and the Catholic Church in 1873, but only in Prussia. This gained strong support from German liberals, who saw the Catholic Church as the bastion of reaction and their greatest enemy. The Catholic element, in turn, saw in the National-Liberals as its worst enemy and formed the Center Party.

Catholics, although nearly a third of the national population, were seldom allowed to hold major positions in the Imperial government, or the Prussian government. Most of the Kulturkampf was fought out in Prussia, but Imperial Germany passed the

After 1870 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck would not tolerate any base of power outside Germany—in Rome—having a say in German affairs. He launched a Kulturkampf ("culture war") against the power of the pope and the Catholic Church in 1873, but only in Prussia. This gained strong support from German liberals, who saw the Catholic Church as the bastion of reaction and their greatest enemy. The Catholic element, in turn, saw in the National-Liberals as its worst enemy and formed the Center Party.

Catholics, although nearly a third of the national population, were seldom allowed to hold major positions in the Imperial government, or the Prussian government. Most of the Kulturkampf was fought out in Prussia, but Imperial Germany passed the

The

The

Popes have always highlighted the inner link between the

Popes have always highlighted the inner link between the

Only in the 19th century, after the breakdown of most Spanish and Portuguese colonies, was the Vatican able to take charge of Catholic missionary activities through its

Only in the 19th century, after the breakdown of most Spanish and Portuguese colonies, was the Vatican able to take charge of Catholic missionary activities through its

The

The

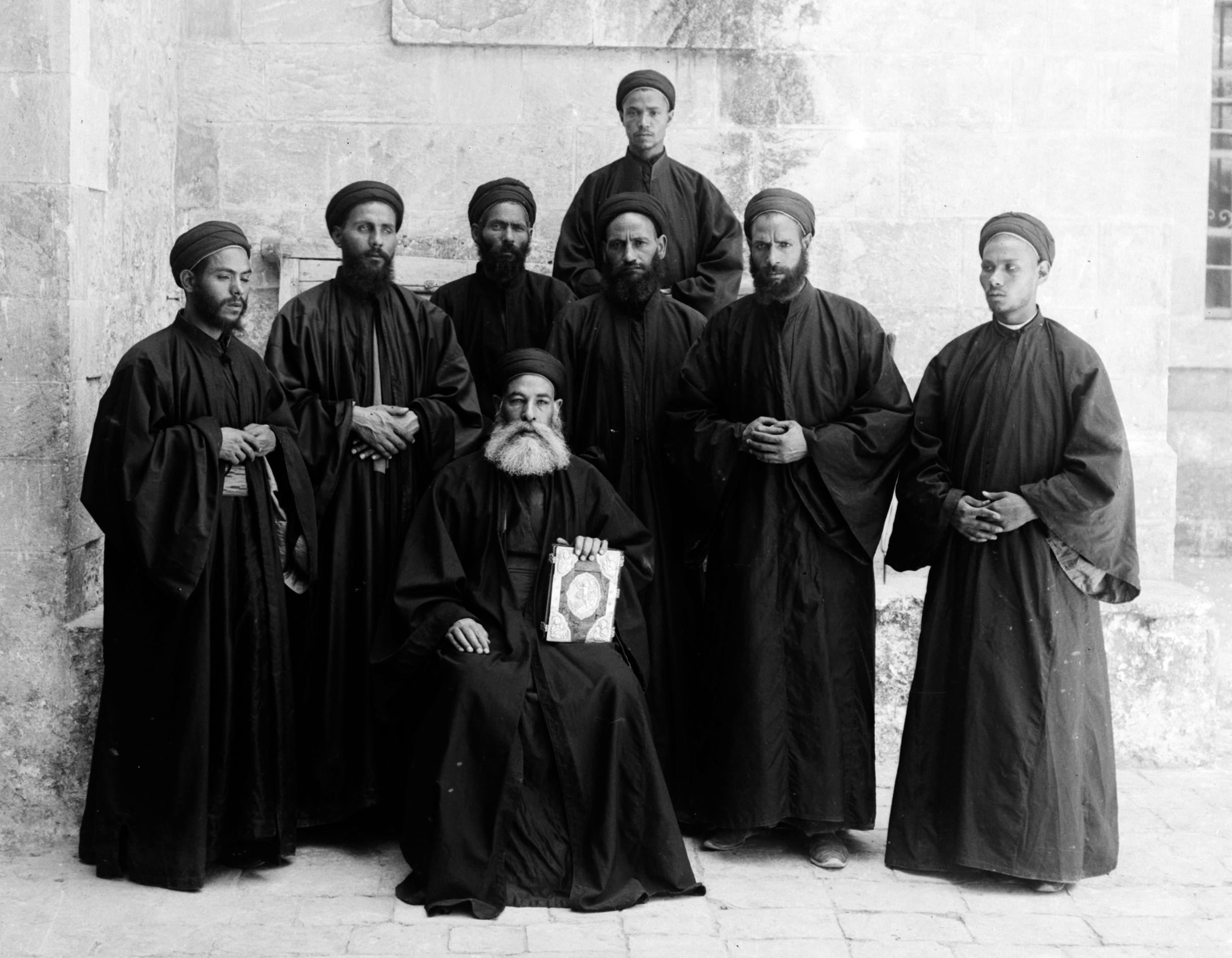

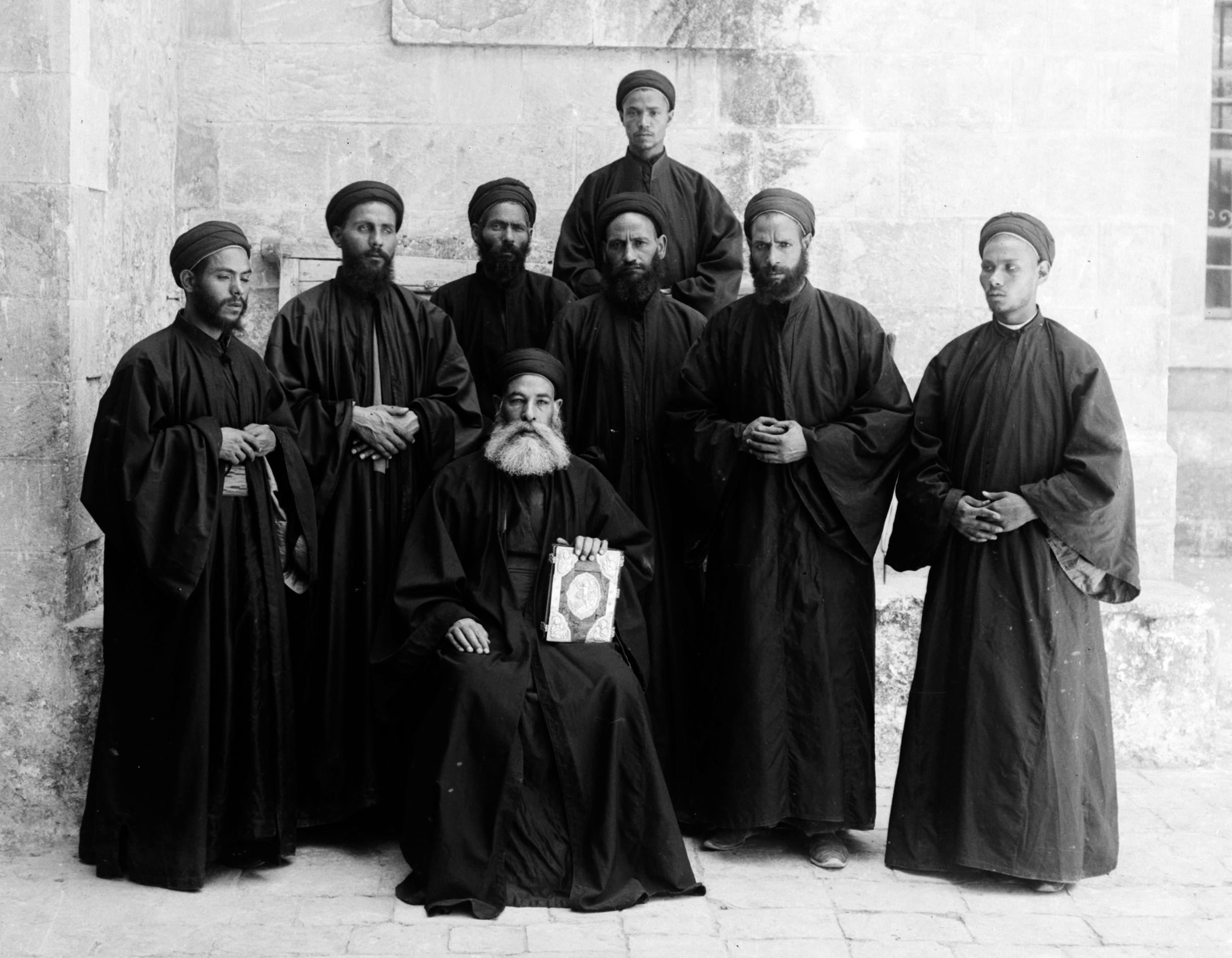

The position of Copts began to improve early in the 19th century under the stability and tolerance of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty. The Coptic community ceased to be regarded by the state as an administrative unit. In 1855 the jizya tax was abolished by Sa'id Pasha. Shortly thereafter, the Copts started to serve in the Egyptian army.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Coptic Church underwent phases of new development. In 1853, Coptic Pope Cyril IV established the first modern Coptic schools, including the first Egyptian school for girls. He also founded a printing press, which was only the second national press in the country. Coptic Pope established very friendly relations with other denominations, to the extent that when the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria had to absent himself from the country for a long period of time, he left his Church under the guidance of the Coptic Patriarch.

The Theological College of the School of Alexandria was reestablished in 1893. It began its new history with five students, one of whom was later to become its dean.

The position of Copts began to improve early in the 19th century under the stability and tolerance of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty. The Coptic community ceased to be regarded by the state as an administrative unit. In 1855 the jizya tax was abolished by Sa'id Pasha. Shortly thereafter, the Copts started to serve in the Egyptian army.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Coptic Church underwent phases of new development. In 1853, Coptic Pope Cyril IV established the first modern Coptic schools, including the first Egyptian school for girls. He also founded a printing press, which was only the second national press in the country. Coptic Pope established very friendly relations with other denominations, to the extent that when the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria had to absent himself from the country for a long period of time, he left his Church under the guidance of the Coptic Patriarch.

The Theological College of the School of Alexandria was reestablished in 1893. It began its new history with five students, one of whom was later to become its dean.

online

* Gilley, Sheridan, and Brian Stanley, eds. ''The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8, World Christianities c.1815-c.1914'' (2006

excerpt

* * Hastings, Adrian, ed. ''A World History of Christianity'' (1999) 608pp * Latourette, Kenneth Scott. ''Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, I: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: Background and the Roman Catholic Phase''; ''Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, II: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: The Protestant and Eastern Churches''; ''Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, III: The Nineteenth Century Outside Europe: The Americas, the Pacific, Asia and Africa'' (1959–69), detailed survey by leading scholar * MacCulloch, Diarmaid. ''Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years'' (2011) * McLeod, Hugh. ''Religion and the People of Western Europe 1789–1989'' (Oxford UP, 1997) * McLeod, Hugh. ''Piety and Poverty: Working Class Religion in Berlin, London and New York'' (1996) * McLeod, Hugh and Werner Ustorf, eds. ''The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe, 1750–2000'' (Cambridge UP, 2004

online

*

excerpt and text search

* Angold, Michael, ed. ''The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity'' (2006) * Callahan, William J. ''The Catholic Church in Spain, 1875–1998'' (2000). * Gibson, Ralph. ''A Social History of French Catholicism 1789–1914'' (London, 1989) * González Justo L. and Ondina E. González, ''Christianity in Latin America: A History'' (2008) * Hastings, Adrian. ''A History of English Christianity 1920–2000'' (2001) * Hope, Nicholas. ''German and Scandinavian Protestantism 1700–1918'' (1999) * Lannon, Frances. ''Privilege, Persecution and Prophecy: The Catholic Church in Spain 1875–1975'' (1987) * Lippy, Charles H., ed. ''Encyclopedia of the American Religious Experience'' (3 vol. 1988) * Lynch, John. ''New Worlds: A Religious History of Latin America'' (2012) * McLeod, Hugh, ed. ''European Religion in the Age of Great Cities 1830–1930'' (1995) * Noll, Mark A. ''A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada'' (1992) * Rosman, Doreen. ''The Evolution of the English Churches, 1500–2000'' (2003) 400pp

''Dictionary of the History of Ideas'': Christianity in History

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 19th Century 19 Christianity in the late modern period

evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

revivals in some largely Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

countries and later the effects of modern biblical scholarship on the churches. Liberal or modernist theology was one consequence of this. In Europe, the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

strongly opposed liberalism and culture wars

A culture war is a cultural conflict between social groups and the struggle for dominance of their values, beliefs, and practices. It commonly refers to topics on which there is general societal disagreement and polarization in societal value ...

launched in Germany, Italy, Belgium and France. It strongly emphasized personal piety. In Europe there was a general move away from religious observance and belief in Christian teachings and a move towards secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a sim ...

. In Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, pietistic revivals were common.

Modernism in Christian theology

As the more radical implications of the scientific and cultural influences of the Enlightenment began to be felt in the Protestant churches, especially in the 19th century, Liberal Christianity, exemplified especially by numerous theologians in Germany in the 19th century, sought to bring the churches alongside of the broad revolution thatmodernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

represented. In doing so, new critical approaches to the Bible were developed, new attitudes became evident about the role of religion in society, and a new openness to questioning the nearly universally accepted definitions of Christian orthodoxy began to become obvious.

In reaction to these developments, Christian fundamentalism was a movement to reject the radical influences of philosophical humanism, as this was affecting the Christian religion. Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by atheistic

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists began to appear in various denominations as numerous independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity. Over time, the Fundamentalist Evangelical movement has divided into two main wings, with the label ''Fundamentalist'' following one branch, while ''Evangelical'' has become the preferred banner of the more moderate movement. Although both movements primarily originated in the English speaking world, the majority of Evangelicals now live elsewhere in the world.

After the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, Protestant groups continued to splinter, leading to a range of new theologies. The Enthusiasts

In modern usage, enthusiasm refers to intense enjoyment, interest, or approval expressed by a person. The term is related to playfulness, inventiveness, optimism and high energy. The word was originally used to refer to a person possessed by G ...

were so named because of their emotional zeal. These included the Methodists, the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, and the Baptists. Another group sought to reconcile Christian faith with modernist ideas, sometimes causing them to reject beliefs they considered to be illogical, including the Nicene creed and Chalcedonian Creed

The Chalcedonian Definition (also called the Chalcedonian Creed or the Definition of Chalcedon) is a declaration of Christ's nature (that it is dyophysite), adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. Chalcedon was an early centre of Christ ...

. These included Unitarians and Universalists

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is seen as more far-reaching th ...

. A major issue for Protestants became the degree to which people contribute to their salvation. The debate is often viewed as synergism versus monergism

Monergism is the view within Christian theology which holds that God works through the Holy Spirit to bring about the salvation of an individual through spiritual regeneration, regardless of the individual's cooperation. It is most often asso ...

, though the labels Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and Arminian are more frequently used, referring to the conclusion of the Synod of Dort.

The 19th century saw the rise of Biblical criticism, new knowledge of religious diversity in other continents, and above all the growth of science. This led many Christians to emphasize the brotherhood, to seeing miracles as myths, and to emphasize a moral approach with religion as lifestyle rather than revealed truth.

Liberal Christianity

Liberal Christianity—sometimes called liberal theology—reshaped Protestantism. Liberal Christianity is an umbrella term covering diverse, philosophically informed movements and moods within 19th and 20th century Christianity. Despite its name, liberal Christianity has always been thoroughlyprotean

In Greek mythology, Proteus (; Ancient Greek: Πρωτεύς, ''Prōteus'') is an early prophetic sea-god or god of rivers and oceanic bodies of water, one of several deities whom Homer calls the " Old Man of the Sea" ''(hálios gérôn) ...

. The word ''liberal'' in liberal Christianity does not refer to a leftist political agenda but rather to insights developed during the Age of Enlightenment. Generally speaking, Enlightenment-era liberalism held that people are political creatures and that liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

of thought and expression should be their highest value. The development of liberal Christianity owes a lot to the works of theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher. As a whole, liberal Christianity is a product of a continuing philosophical dialogue.

Protestant Europe

Historian

Historian Kenneth Scott Latourette

Kenneth Scott Latourette (August 6, 1884 – December 26, 1968) was an American historian of China, Japan, and world Christianity.

argues that the outlook for Protestantism at the start of the 19th century was discouraging. It was a regional religion based in northwestern Europe, with an outpost in the sparsely settled United States. It was closely allied with government, as in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Prussia, and especially Great Britain. The alliance came at the expense of independence, as the government made the basic policy decisions, down to such details as the salaries of ministers and location of new churches. The dominant intellectual currents of the Enlightenment promoted rationalism, and most Protestant leaders preached a sort of deism. Intellectually, the new methods of historical and anthropological study undermine automatic acceptance of biblical stories, as did the sciences of geology and biology. Industrialization was a strongly negative factor, as workers who moved to the city seldom joined churches. The gap between the church and the unchurched grew rapidly, and secular forces, based both in socialism and liberalism undermine the prestige of religion. Despite the negative forces, Protestantism demonstrated a striking vitality by 1900. Shrugging off Enlightenment rationalism, Protestants embraced romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, with the stress on the personal and the invisible. Entirely fresh ideas as expressed by Friedrich Schleiermacher, Soren Kierkegaard Soren may refer to:

*Søren, a given name of Scandinavian origin, also spelled ''Sören''

*Suren (disambiguation), a Persian name also rendered as Soren

*3864 Søren, main belt asteroid

*Sōren, also known as ''Chongryon'' and ''Zai-Nihon Chōsenji ...

, Albrecht Ritschl

Albrecht Ritschl (25 March 182220 March 1889) was a German Protestant theologian.

Starting in 1852, Ritschl lectured on systematic theology. According to this system, faith was understood to be irreducible to other experiences, beyond the scop ...

and Adolf von Harnack restored the intellectual power of theology. There was more attention to historic creeds such as the Augsburg, the Heidelberg, and the Westminster confessions. The stirrings of pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

on the Continent, and evangelicalism in Britain expanded enormously, leading the devout away from an emphasis on formality and ritual and toward an inner sensibility toward personal relationship to Christ. Social activities, in education and in opposition to social vices such as slavery, alcoholism and poverty provided new opportunities for social service. Above all, worldwide missionary activity became a highly prized goal, proving quite successful in close cooperation with the imperialism of the British, German, and Dutch empires.

Britain

In England, Anglicans emphasized the historically Catholic components of their heritage, as the High Church element reintroduced vestments and incense into their rituals, against the opposition of Low Church evangelicals. As the Oxford Movement began to advocate restoring traditional Catholic faith and practice to theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

(see Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

), there was felt to be a need for a restoration of the monastic life

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural ex ...

. Anglican priest John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

established a community of men at Littlemore

Littlemore is a district and civil parish in Oxford, England. The civil parish includes part of Rose Hill. It is about southeast of the city centre of Oxford, between Rose Hill, Blackbird Leys, Cowley, and Sandford-on-Thames. The 2011 Censu ...

near Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in the 1840s. From then forward, there have been many communities of monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s, friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

s, sisters, and nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s established within the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

. In 1848, Mother Priscilla Lydia Sellon founded the Anglican Sisters of Charity and became the first woman to take religious vows within the Anglican Communion since the English Reformation. In October 1850, the first building specifically built for the purpose of housing an Anglican Sisterhood was consecrated at Abbeymere in Plymouth. It housed several schools for the destitute, a laundry, printing press, and a soup kitchen. From the 1840s and throughout the following hundred years, religious orders for both men and women proliferated in Britain, America and elsewhere.

Germany

Two main developments reshaped religion in Germany. Across the land, there was a movement to unite the largerLutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

and the smaller Reformed Protestant churches. The churches themselves brought this about in Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

, Nassau, and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. However, in Prussia, King Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

was determined to handle unification entirely on his own terms, without consultation. His goal was to unify the Protestant churches, and to impose a single standardized liturgy, organization, and even architecture. The long-term goal was to have fully centralized royal control of all the Protestant churches. In a series of proclamations over several decades the ''Church of the Prussian Union'' was formed, bringing together the more numerous Lutherans, and the less numerous Reformed Protestants. The government of Prussia now had full control over church affairs, with the king himself recognized as the leading bishop. Opposition to unification came from the "Old Lutherans

Old Lutherans were originally German Lutherans in the Kingdom of Prussia, notably in the Province of Silesia, who refused to join the Prussian Union of churches in the 1830s and 1840s. Prussia's king Frederick William III was determined to uni ...

" in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

who clung tightly to the theological and liturgical forms they had followed since the days of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

. The government attempted to crack down on them, so they went underground. Tens of thousands migrated, to South Australia, and especially to the United States, where they formed what is now the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, which remains a conservative denomination. Finally, in 1845, the new king, Frederick William IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

, offered a general amnesty and allowed the Old Lutherans to form a separate church association with only nominal government control.

From the religious point of view of the typical Catholic or Protestant, major changes were underway in terms of a much more personalized religiosity that focused on the individual more than the church or the ceremony. The rationalism of the late 19th century faded away, and there was a new emphasis on the psychology and feeling of the individual, especially in terms of contemplating sinfulness, redemption, and the mysteries and the revelations of Christianity. Pietistic revivals were common among Protestants.

American trends

The main trends in Protestantism included the rapid growth of Methodist and Baptists denominations, and the steady growth among Presbyterians, Congregationalists and Anglicans. After 1830 German Lutherans arrived in large numbers; after 1860 Scandinavian Lutherans arrived. The Pennsylvania Dutch Protestant sects (and Lutherans) grew through high birth rates.Second Great Awakening

TheSecond Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

(1790-1840s) was the second great religious revival in America. Unlike the First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

of the 18th century, it focused on the unchurched and sought to instill in them a deep sense of personal salvation as experienced in revival meeting

A revival meeting is a series of Christian religious services held to inspire active members of a church body to gain new converts and to call sinners to repent. Nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon said, "Many blessings may come t ...

s. It also sparked the beginnings of groups such as the Mormons and the Holiness movement. Leaders included Asahel Nettleton, Edward Payson

Edward Payson (July 25, 1783October 22, 1827) was an American Congregational preacher. He was born at Rindge, New Hampshire, where his father, Rev. Seth Payson (1758–1820), was pastor of the Congregational Church. His uncle, Phillips Payson (1 ...

, James Brainerd Taylor, Charles Grandison Finney

Charles Grandison Finney (August 29, 1792 – August 16, 1875) was an American Presbyterian minister and leader in the Second Great Awakening in the United States. He has been called the "Father of Old Revivalism." Finney rejected much of trad ...

, Lyman Beecher

Lyman Beecher (October 12, 1775 – January 10, 1863) was a Presbyterian minister, and the father of 13 children, many of whom became noted figures, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Edward Beecher, Isabella B ...

, Barton W. Stone, Peter Cartwright, and James Finley.

In New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, the renewed interest in religion inspired a wave of social activism. In western New York, the spirit of revival encouraged the emergence of the Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the United States frontier during the Second Great Awakening (17 ...

, the Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by J ...

, Adventism

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher W ...

, and the Holiness movement. Especially in the west—at Cane Ridge, Kentucky

Cane Ridge was the site, in 1801, of a huge camp meeting that drew thousands of people and had a lasting influence as one of the landmark events of the Second Great Awakening, which took place largely in frontier areas of the United States. T ...

and in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

—the revival strengthened the Methodists and the Baptists and introduced into America a new form of religious expression—the Scottish camp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier ...

.

The Second Great Awakening made its way across the frontier territories, fed by intense longing for a prominent place for God in the life of the new nation, a new liberal attitude toward fresh interpretations of the Bible, and a contagious experience of zeal for authentic spirituality. As these revivals spread, they gathered converts to Protestant sects of the time. The revivals eventually moved freely across denominational lines with practically identical results and went farther than ever toward breaking down the allegiances which kept adherents to these denominations loyal to their own. Consequently, the revivals were accompanied by a growing dissatisfaction with Evangelical churches and especially with the doctrine of Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, which was nominally accepted or at least tolerated in most Evangelical churches at the time. Various unaffiliated movements arose that were often restorationist in outlook, considering contemporary Christianity of the time to be a deviation from the true, original Christianity. These groups attempted to transcend Protestant denominationalism and orthodox Christian creeds to restore Christianity to its original form.

Barton W. Stone, founded a movement at Cane Ridge

Cane Ridge was the site, in 1801, of a huge camp meeting that drew thousands of people and had a lasting influence as one of the landmark events of the Second Great Awakening, which took place largely in frontier areas of the United States. Th ...

, Kentucky; they called themselves simply Christians. The second began in western Pennsylvania and was led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell; they used the name Disciples of Christ. Both groups sought to restore the whole Christian church on the pattern set forth in the New Testament, and both believed that creeds kept Christianity divided. In 1832 they merged.McAlister, Lester G. and Tucker, William E. (1975), ''Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)'', St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press,

Mormonism

The Mormon faith emerged from the Latter Day Saint movement in upstate New York in the 1830s. After several schisms and multiple relocations to escape intense hostility, the largest group,The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

(LDS Church), migrated to Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

. They established a theocracy under Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as ch ...

, and came into conflict with the United States government. It tried to suppress the church because of its polygamy and theocracy. Compromises were finally reached in the 1890s, allowing the church to abandon polygamy and flourish.

Adventism

Adventism

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher W ...

is a Christian eschatological belief that looks for the imminent Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messian ...

of Jesus to inaugurate the Kingdom of God. This view involves the belief that Jesus will return to receive those who have died in Christ and those who are awaiting his return, and that they must be ready when he returns. The Millerites

The Millerites were the followers of the teachings of William Miller, who in 1831 first shared publicly his belief that the Second Advent of Jesus Christ would occur in roughly the year 1843–1844. Coming during the Second Great Awakening, his ...

, the most well-known family of the Adventist movements, were the followers of the teachings of William Miller, who, in 1833, first shared publicly his belief in the coming Second Advent of Jesus Christ in c.1843. They emphasized apocalyptic teachings anticipating the end of the world and did not look for the unity of Christendom but busied themselves in preparation for Christ's return. From the Millerites descended the Seventh-day Adventists and the Advent Christian Church. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is the largest of several Adventist groups which arose from the Millerite movement of the 1840s. Miller predicted on the basis of and the day-year principle

The year principle, year principle or year-for-a-day principle is a method of interpretation of Bible prophecy in which the word ''day'' in prophecy is considered to be symbolic of a ''year'' of actual time. It was the method used by most of the ...

that Jesus Christ would return to Earth on 22 October 1844. When this did not happen, most of his followers disbanded and returned to their original churches.

Holiness movement

The Methodists of the 19th century continued the interest in Christian holiness that had been started by their founder, John Wesley. In 1836 two Methodist women, Sarah Worrall Lankford andPhoebe Palmer

Phoebe Palmer (December 18, 1807 – November 2, 1874) was a Methodist evangelist and writer who promoted the doctrine of Christian perfection. She is considered one of the founders of the Holiness movement within Methodist Christianity.

Ea ...

, started the Tuesday Meeting for the Promotion of Holiness in New York City. A year later, Methodist minister Timothy Merritt founded a journal called the ''Guide to Christian Perfection'' to promote the Wesleyan

Wesleyan theology, otherwise known as Wesleyan– Arminian theology, or Methodist theology, is a theological tradition in Protestant Christianity based upon the ministry of the 18th-century evangelical reformer brothers John Wesley and Charle ...

message of Christian holiness.

In 1837, Palmer experienced what she called entire sanctification. She began leading the Tuesday Meeting for the Promotion of Holiness. At first only women attended these meetings, but eventually Methodist bishops and other clergy members began to attend them also. In 1859, she published ''The Promise of the Father'', in which she argued in favor of women in ministry, later to influence Catherine Booth

Catherine Booth (''née'' Mumford, 17 January 1829 – 4 October 1890) was co-founder of The Salvation Army, along with her husband William Booth. Because of her influence in the formation of The Salvation Army she was known as the 'Mothe ...

, co-founder of the Salvation Army. The practice of ministry by women became common but not universal within the branches of the holiness movement.

The first distinct "holiness" camp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier ...

convened in Vineland, New Jersey in 1867 and attracted as many as 10,000 people. Ministers formed the National Camp Meeting Association for the Promotion of Holiness and agreed to conduct a similar gathering the next year. Later, this association became the Christian Holiness Partnership

The Christian Holiness Partnership is an international organization of individuals, organizational and denominational affiliates within the holiness movement. It was founded under the leadership of Rev. John Swanel Inskip in 1867 as the National ...

. The third National Camp Meeting met at Round Lake, New York

Round Lake is a village in Saratoga County, New York, United States. The population was 1,245 at the 2020 census. The name is derived from a circular lake adjacent to the village. In 1975, the Round Lake Historic District, which encompasses the v ...

. This time the national press attended, and write-ups appeared in numerous papers. Robert and Hannah Smith were among those who took the holiness message to England, and their ministries helped lay the foundation for the Keswick Convention

The Keswick Convention is an annual gathering of conservative evangelical Christians in Keswick, in the English county of Cumbria.

The Christian theological tradition of Keswickianism, also known as the Higher Life movement, became popularised ...

.

In the 1870s, the holiness movement spread to Great Britain, where it was sometimes called the Higher Life movement

The Higher Life movement, also known as the Keswick movement or Keswickianism, is a Protestant theological tradition within evangelical Christianity that espouses a distinct teaching on the doctrine of entire sanctification.

Its name comes ...

after the title of William Boardman's book, ''The Higher Life''. Higher Life conferences were held at Broadlands

Broadlands is an English country house, located in the civil parish of Romsey Extra, near the town of Romsey in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England. The formal gardens and historic landscape of Broadlands are Grade II* listed on th ...

and Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1874 and in Brighton and Keswick in 1875. The Keswick Convention soon became the British headquarters for the movement. The Faith Mission Faith mission is a term used most frequently among evangelical Christians to refer to a missionary organization with an approach to evangelism that encourages its missionaries to "trust in God to provide the necessary resources". These missionaries ...

in Scotland was one consequence of the British holiness movement. Another was a flow of influence from Britain back to the United States. In 1874, Albert Benjamin Simpson

Albert Benjamin Simpson (December 15, 1843 – October 29, 1919), also known as A. B. Simpson, was a Canadian preacher, theologian, author, and founder of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (C&MA), an evangelical denomination with an emphasis ...

read Boardman's ''Higher Christian Life'' and felt the need for such a life himself. He went on to found the Christian and Missionary Alliance

The Alliance World Fellowship is the international governing body of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (The Alliance, also C&MA and CMA). The Alliance is an evangelical Protestant denomination within the Higher Life movement of Christianity ...

.

Third Great Awakening

TheThird Great Awakening

The Third Great Awakening refers to a historical period proposed by William G. McLoughlin that was marked by religious activism in American history and spans the late 1850s to the early 20th century. It influenced pietistic Protestant denominat ...

was a period of religious activism in American history from the late 1850s to the 20th century. It affected pietistic Protestant denominations and had a strong sense of social activism. It gathered strength from the postmillennial theology that the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messian ...

of Christ would come after humankind had reformed the entire earth. The Social Gospel Movement gained its force from the awakening, as did the worldwide missionary movement. New groupings emerged, such as the Holiness

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

and Nazarene movements, and Christian Science.Robert William Fogel, ''The Fourth Great Awakening & the Future of Egalitarianism'' University of Chicago Press, 20000 excerpt

/ref> Significant names include

Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 26, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Massa ...

, Ira D. Sankey, William Booth

William Booth (10 April 182920 August 1912) was an English Methodist preacher who, along with his wife, Catherine, founded the Salvation Army and became its first " General" (1878–1912). His 1890 book In Darkest England and The Way Out o ...

and Catherine Booth (founders of the Salvation Army), Charles Spurgeon

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (19 June 1834 – 31 January 1892) was an English Particular Baptist preacher.

Spurgeon remains highly influential among Christians of various denominations, among whom he is known as the "Prince of Preachers". He wa ...

, and James Caughey. Hudson Taylor

James Hudson Taylor (; 21 May 1832 – 3 June 1905) was a British Baptist Christian missionary to China and founder of the China Inland Mission (CIM, now OMF International). Taylor spent 51 years in China. The society that he began was respons ...

began the China Inland Mission

OMF International (formerly Overseas Missionary Fellowship and before 1964 the China Inland Mission) is an international and interdenominational Evangelical Christianity, Christian missionary society with an international centre in Singapore. It ...

and Thomas John Barnardo

Thomas John Barnardo (4 July 184519 September 1905) was an Irish-born philanthropist and founder and director of homes for poor and deprived children. From the foundation of the first Barnardo's home in 1867 to the date of Barnardo's death, ne ...

founded his famous orphanages.

Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879. She also founded ''The Christian Science Monitor'', a Pulitzer Prize-winning se ...

introduced Christian Science, which gained a national following. In 1880, the Salvation Army denomination arrived in America. Although its theology was based on ideals expressed during the Second Great Awakening, its focus on poverty was of the Third. The Society for Ethical Culture, established in New York in 1876 by Felix Adler, attracted a Reform Jewish clientele. Charles Taze Russell

Charles Taze Russell (February 16, 1852 – October 31, 1916), or Pastor Russell, was an American Christian restorationist minister from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and founder of what is now known as the Bible Student movement. He was an ...

founded a Bible Student movement

The Bible Student movement is a Millennialist Restorationist Christian movement. It emerged from the teachings and ministry of Charles Taze Russell (1852–1916), also known as Pastor Russell, and his founding of the Zion's Watch Tower Tract ...

now known as the Jehovah's Witnesses.

Roman Catholicism

France

The Catholic Church lost all its lands and buildings during theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, and these were sold off or came under the control of local governments. The more radical elements of the Revolution tried to suppress the church, but Napoleon came to a compromise with the pope in the Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace-Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation ...

that restored much of its status. The bishop still ruled his diocese (which was aligned with the new department boundaries), but could only communicate with the pope through the government in Paris. Bishops, priests, nuns and other religious people were paid salaries by the state. All the old religious rites and ceremonies were retained, and the government maintained the religious buildings. The Church was allowed to operate its own seminaries and to some extent local schools as well, although this became a central political issue into the 20th century. Bishops were much less powerful than before, and had no political voice. However, the Catholic Church reinvented itself and put a new emphasis on personal religiosity that gave it a hold on the psychology of the faithful.

France remained basically Catholic. The 1872 census counted 36 million people, of whom 35.4 million were listed as Catholics, 600,000 as Protestants, 50,000 as Jews and 80,000 as freethinkers. The Revolution failed to destroy the Catholic Church, and Napoleon's concordat of 1801 restored its status. The return of the Bourbons in 1814 brought back many rich nobles and landowners who supported the Church, seeing it as a bastion of conservatism and monarchism. However the monasteries with their vast land holdings and political power were gone; much of the land had been sold to urban entrepreneurs who lacked historic connections to the land and the peasants.Robert Gildea, ''Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799–1914''(2008) p 120

Few new priests were trained in the 1790–1814 period, and many left the church. The result was that the number of parish clergy plunged from 60,000 in 1790 to 25,000 in 1815, many of them elderly. Entire regions, especially around Paris, were left with few priests. On the other hand, some traditional regions held fast to the faith, led by local nobles and historic families.

The comeback was very slow in the larger cities and industrial areas. With systematic missionary work and a new emphasis on liturgy and devotions to the Virgin Mary, plus support from Napoleon III, there was a comeback. In 1870 there were 56,500 priests, representing a much younger and more dynamic force in the villages and towns, with a thick network of schools, charities and lay organizations. Conservative Catholics held control of the national government, 1820–1830, but most often played secondary political roles or had to fight the assault from republicans, liberals, socialists and seculars.

Throughout the lifetime of the Third Republic (1870–1940) there were battles over the status of the Catholic Church. The French clergy and bishops were closely associated with the Monarchists and many of its hierarchy were from noble families. Republicans were based in the anticlerical middle class who saw the Church's alliance with the monarchists as a political threat to republicanism, and a threat to the modern spirit of progress. The Republicans detested the church for its political and class affiliations; for them, the church represented outmoded traditions, superstition and monarchism.Philippe Rigoulot, "Protestants and the French nation under the Third Republic: Between recognition and assimilation," ''National Identities,'' March 2009, Vol. 11 Issue 1, pp 45–57

The Republicans were strengthened by Protestant and Jewish support. Numerous laws were passed to weaken the Catholic Church. In 1879, priests were excluded from the administrative committees of hospitals and of boards of charity. In 1880, new measures were directed against the religious congregations. From 1880 to 1890 came the substitution of lay women for nuns in many hospitals. Napoleon's 1801 Concordat continued in operation but in 1881, the government cut off salaries to priests it disliked.

The 1882 school laws of Republican Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

set up a national system of public schools that taught strict puritanical morality but no religion. For a while privately funded Catholic schools were tolerated. Civil marriage became compulsory, divorce was introduced and chaplains were removed from the army.

When Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-ol ...

became pope in 1878 he tried to calm Church-State relations. In 1884 he told French bishops not to act in a hostile manner to the State. In 1892 he issued an encyclical advising French Catholics to rally to the Republic and defend the Church by participating in Republican politics. This attempt at improving the relationship failed.Frank Tallett and Nicholas Atkin, ''Religion, society, and politics in France since 1789'' (1991) p. 152

Deep-rooted suspicions remained on both sides and were inflamed by the Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

. Catholics were for the most part anti-dreyfusard. The Assumptionists published anti-Semitic and anti-republican articles in their journal ''La Croix''. This infuriated Republican politicians, who were eager to take revenge. Often they worked in alliance with Masonic lodges. The Waldeck-Rousseau Ministry (1899–1902) and the Combes Ministry (1902–05) fought with the Vatican over the appointment of bishops.

Chaplains were removed from naval and military hospitals (1903–04), and soldiers were ordered not to frequent Catholic clubs (1904). Combes as Prime Minister in 1902, was determined to thoroughly defeat Catholicism. He closed down all parochial schools in France. Then he had parliament reject authorisation of all religious orders. This meant that all fifty four orders were dissolved and about 20,000 members immediately left France, many for Spain.

In 1905 the 1801 Concordat was abrogated; Church and State were separated. All Church property was confiscated. Public worship was given over to associations of Catholic laymen who controlled access to churches. In practise, Masses and rituals continued. The Church was badly hurt and lost half its priests. In the long run, however, it gained autonomy—for the State no longer had a voice in choosing bishops and Gallicanism was dead.

Germany

Among Catholics there was a sharp increase in popular pilgrimages. In 1844 alone, half a million pilgrims made a pilgrimage to the city of Trier in the Rhineland to view theSeamless robe of Jesus

The Seamless Robe of Jesus (also known as the Holy Robe, Holy Tunic, Holy Coat, Honorable Robe, and Chiton of the Lord) is the robe said to have been worn by Jesus during or shortly before his crucifixion. Competing traditions claim that the ro ...

, said to be the robe that Jesus wore on the way to his crucifixion. Catholic bishops in Germany had historically been largely independent Of Rome, but now the Vatican exerted increasing control, a new "ultramontanism

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by th ...

" of Catholics highly loyal to Rome. A sharp controversy broke out in 1837–38 in the largely Catholic Rhineland over the religious education of children of mixed marriages, where the mother was Catholic and the father Protestant. The government passed laws to require that these children always be raised as Protestants, contrary to Napoleonic law that had previously prevailed and allowed the parents to make the decision. It put the Catholic Archbishop under house arrest. In 1840, the new King Frederick William IV sought reconciliation and ended the controversy by agreeing to most of the Catholic demands. However Catholic memories remained deep and led to a sense that Catholics always needed to stick together in the face of an untrustworthy government.

Kulturkampf

After 1870 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck would not tolerate any base of power outside Germany—in Rome—having a say in German affairs. He launched a Kulturkampf ("culture war") against the power of the pope and the Catholic Church in 1873, but only in Prussia. This gained strong support from German liberals, who saw the Catholic Church as the bastion of reaction and their greatest enemy. The Catholic element, in turn, saw in the National-Liberals as its worst enemy and formed the Center Party.

Catholics, although nearly a third of the national population, were seldom allowed to hold major positions in the Imperial government, or the Prussian government. Most of the Kulturkampf was fought out in Prussia, but Imperial Germany passed the

After 1870 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck would not tolerate any base of power outside Germany—in Rome—having a say in German affairs. He launched a Kulturkampf ("culture war") against the power of the pope and the Catholic Church in 1873, but only in Prussia. This gained strong support from German liberals, who saw the Catholic Church as the bastion of reaction and their greatest enemy. The Catholic element, in turn, saw in the National-Liberals as its worst enemy and formed the Center Party.

Catholics, although nearly a third of the national population, were seldom allowed to hold major positions in the Imperial government, or the Prussian government. Most of the Kulturkampf was fought out in Prussia, but Imperial Germany passed the Pulpit Law The Pulpit Law (German ''Kanzelparagraph'') was a section (§ 130a) to the ''Strafgesetzbuch'' (the German Criminal Code) passed by the Reichstag in 1871 during the German Kulturkampf or fight against the Catholic Church. It made it a crime for any ...

which made it a crime for any cleric to discuss public issues in a way that displeased the government. Nearly all Catholic bishops, clergy, and laymen rejected the legality of the new laws, and were defiant facing the increasingly heavy penalties and imprisonments imposed by Bismarck's government. Historian Anthony Steinhoff reports the casualty totals:

:As of 1878, only three of eight Prussian dioceses still had bishops, some 1,125 of 4,600 parishes were vacant, and nearly 1,800 priests ended up in jail or in exile....Finally, between 1872 and 1878, numerous Catholic newspapers were confiscated, Catholic associations and assemblies were dissolved, and Catholic civil servants were dismissed merely on the pretence of having Ultramontane sympathies.

Bismarck underestimated the resolve of the Catholic Church and did not foresee the extremes that this struggle would entail. The Catholic Church denounced the harsh new laws as anti-catholic and mustered the support of its rank and file voters across Germany. In the following elections, the Center Party won a quarter of the seats in the Imperial Diet. The conflict ended after 1879 because Pius IX died in 1878 and Bismarck broke with the Liberals to put his main emphasis on tariffs, foreign policy, and attacking socialists. Bismarck negotiated with the conciliatory new pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-ol ...

. Peace was restored, the bishops returned and the jailed clerics were released. Laws were toned down or taken back (Mitigation Laws 1880–1883 and Peace Laws 1886–87), but the main regulations such as the Pulpit Law The Pulpit Law (German ''Kanzelparagraph'') was a section (§ 130a) to the ''Strafgesetzbuch'' (the German Criminal Code) passed by the Reichstag in 1871 during the German Kulturkampf or fight against the Catholic Church. It made it a crime for any ...

and the laws concerning education, civil registry (incl. marriage) or religious disaffiliation remained in place. The Center Party gained strength and became an ally of Bismarck, especially when he attacked socialism.

First Vatican Council

On 7 February 1862, Pope Pius IX issued the papal constitution '' Ad Universalis Ecclesiae'', dealing with the conditions for admission toCatholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life

Consecrated life (also known as religious life) is a state of life in the Catholic Church lived by those faithful who are called to follow Jesus Christ in a more ex ...

s of men in which solemn vows

A solemn vow is a certain vow ("a deliberate and free promise made to God about a possible and better good") taken by an individual during or after novitiate in a Catholic religious institute. It is solemn insofar as the Church recognizes it a ...

were prescribed.

The doctrine of papal primacy was further developed in 1870 at the First Vatican Council, which declared that "in the disposition of God the Roman church holds the preeminence of ordinary power over all the other churches". This council also affirmed the dogma of papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks '' ex cathedra'' is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apos ...

, (declaring that the infallibility of the Christian community extends to the pope himself, when he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church), and of papal supremacy (supreme, full, immediate, and universal ordinary jurisdiction of the pope).

The most substantial body of defined doctrine on the subject is found in ''Pastor aeternus

''Pastor aeternus'' ("First Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ"), was issued by the First Vatican Council, July 18, 1870. The document defines four doctrines of the Catholic faith: the apostolic primacy conferred on Peter, the perpe ...

'', the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ of Vatican Council I. This document declares that "in the disposition of God the Roman church holds the preeminence of ordinary power over all the other churches." This council also affirmed the dogma of papal infallibility.

The council defined a twofold primacy of Peter, one in papal teaching on faith and morals (the charism of infallibility), and the other a primacy of jurisdiction involving government and discipline of the Church, submission to both being necessary to Catholic faith and salvation.

It rejected the ideas that papal decrees have "no force or value unless confirmed by an order of the secular power" and that the pope's decisions can be appealed to an ecumenical council "as to an authority higher than the Roman Pontiff."

Paul Collins argues that "(the doctrine of papal primacy as formulated by the First Vatican Council) has led to the exercise of untrammelled papal power and has become a major stumbling block in ecumenical relationships with the Orthodox (who consider the definition to be heresy) and Protestants."

Before the council in 1854, Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of bishops, proclaimed the dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Isla ...

of the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth w ...

.

Social teachings

The

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

brought many concerns about the deteriorating working and living conditions of urban workers. Influenced by the German Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel Freiherr von Ketteler

Baron Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler (25 December 181113 July 1877) was a German theologian and politician who served as Bishop of Mainz. His social teachings became influential during the papacy of Leo XIII and his encyclical '' Rerum novarum'' ...

, in 1891, Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

published the encyclical '' Rerum novarum'', which set in context Catholic social teaching in terms that rejected socialism but advocated the regulation of working conditions. ''Rerum novarum'' argued for the establishment of a living wage and the right of workers to form trade unions.Duffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), p. 240

Veneration of Mary

Popes have always highlighted the inner link between the

Popes have always highlighted the inner link between the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

as Mother of God

''Theotokos'' (Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are ''Dei Genitrix'' or ''Deipara'' (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations ar ...

and the full acceptance of Jesus Christ as Son of God.

Since the 19th century, they were highly important for the development of mariology

Mariology is the theological study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Mariology seeks to relate doctrine or dogma about Mary to other doctrines of the faith, such as those concerning Jesus and notions about redemption, intercession and grace. Chri ...

to explain the veneration of Mary

Marian devotions are external pious practices directed to the person of Mary, mother of God, by members of certain Christian traditions. They are performed in Catholicism, High Church Lutheranism, Anglo-Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy and Orie ...

through their decisions not only in the area of Marian beliefs (Mariology) but also Marian practices and devotions. Before the 19th century, popes promulgated Marian veneration by authorizing new Marian feast days

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context does ...

, prayers, initiatives, and the acceptance and support of Marian congregations. Since the 19th century, popes began to use encyclicals more frequently. Thus Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-ol ...

, the Rosary Pope

The Mariology of the popes is the theology, theological study of the influence that the popes have had on the development, formulation and transformation of the Roman Catholic Church's doctrines and devotions relating to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

...

, issued eleven Marian encyclicals. Recent popes promulgated the veneration of the Blessed Virgin with two dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Isla ...

s: Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

with the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth w ...

in 1854, and the Assumption of Mary

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution '' Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by ...

in 1950 by Pope Pius XII. Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

, Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

, and Pius XII

Pius ( , ) Latin for "pious", is a masculine given name. Its feminine form is Pia.

It may refer to:

People Popes

* Pope Pius (disambiguation)

* Antipope Pius XIII (1918-2009), who led the breakaway True Catholic Church sect

Given name

* Pius ...

facilitated the veneration of Marian apparition

A Marian apparition is a reported supernatural appearance by Mary, the mother of Jesus, or a series of related such appearances during a period of time.

In the Catholic Church, in order for a reported appearance to be classified as a Marian a ...

s such as in Lourdes

Lourdes (, also , ; oc, Lorda ) is a market town situated in the Pyrenees. It is part of the Hautes-Pyrénées department in the Occitanie region in southwestern France. Prior to the mid-19th century, the town was best known for the Châ ...

and Fátima.

Anti-clericalism, secularism and socialism

In many revolutionary movements the church was denounced for its links with the established regimes. Liberals in particular targeted the Catholic Church as the great enemy. Thus, for example, after theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

and the Mexican Revolution there was a distinct anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

tone in those countries that exists to this day. Socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

in particular was in many cases openly hostile to religion; Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

condemned all religion as the "opium of the people

The opium of the people (or opium of the masses) (german: Opium des Volkes) is a dictum used in reference to religion, derived from a frequently paraphrased statement of German sociologist and economic theorist Karl Marx: "Religion is the opium ...

," as he considered it a false sense of hope in an afterlife withholding the people from facing their worldly situation.

In the History of Latin America

The term ''Latin America'' primarily refers to the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries in the New World.

Before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the region was home to many indigenous peoples, a number of ...

, a succession of anti-clerical liberal regimes came to power beginning in the 1830s. The confiscation of Church properties and restrictions on priests and bishops generally accompanied secularist, reforms.

Jesuits

Only in the 19th century, after the breakdown of most Spanish and Portuguese colonies, was the Vatican able to take charge of Catholic missionary activities through its

Only in the 19th century, after the breakdown of most Spanish and Portuguese colonies, was the Vatican able to take charge of Catholic missionary activities through its Propaganda Fide

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

organization.

During this period, the Church faced colonial abuses from the Portuguese and Spanish governments. In South America, the Jesuits protected native peoples from enslavement by establishing semi-independent settlements called reductions. Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He ...

, challenging Spanish and Portuguese sovereignty, appointed his own candidates as bishops in the colonies, condemned slavery and the slave trade in 1839 (papal bull ''In supremo apostolatus

''In supremo apostolatus'' is a papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XVI regarding the institution of slavery. Issued on December 3, 1839, as a result of a broad consultation among the College of Cardinals, the bull resoundingly denounces both the s ...

''), and approved the ordination of native clergy in spite of government racism.Duffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), p. 221

Africa

By the close of the 19th century, new technologies and superior weaponry had allowed European powers to gain control of most of the African interior. The new rulers introduced a cash economy which required African people to become literate and so created a great demand for schools. At the time, the only possibility open to Africans for a western education was through Christian missionaries. Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa and built schools, monasteries, and churches.Hastings, ''The Church in Africa'' (2004), pp. 397–410Eastern Orthodox Church

Greece

Even several decades before the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, most ofGreece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

had come under Ottoman rule. During this time, there were several revolt attempts by Greeks to gain independence from Ottoman control. In 1821, The Greek revolution was officially declared and by the end of the month, the Peloponnese was in open revolt against the Turks. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople had issued statements condemning and even anathematizing the revolutionaries so as to protect the Greeks of Constantinople from reprisals by the Ottoman Turks.

These statements, however, failed to convince anyone, least of all the Turkish government, which on Easter Day in 1821 had the Patriarch Gregory V

Gregory may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gregory (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Gregory (surname), a surname

Places Australia

* Gregory, Queensland, a town in the Shire o ...

hanged from the main gate of the patriarchal residence as a public example by order of the Sultan; this was followed by a massacre of the Greek population of Constantinople. The brutal execution of Gregory V, especially on the day of Easter Sunday, shocked and infuriated the Greeks. It also caused protests in the rest of Europe and reinforced the movement of Philhellenism. There are references that during the Greek War of Independence, many revolutionaries engraved on their swords the name of Gregory, seeking revenge.

With the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label= Greek, Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, wh ...

, the government decided to take control of the church, breaking away from the patriarch in Constantinople. The government declared the church to be autocephalous

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern O ...

in 1833 in a political decision of the Bavarian Regents acting for King Otto, who was a minor. The decision roiled Greek politics for decades as royal authorities took increasing control. The new status was finally recognized as such by the Patriarchate in 1850, under compromise conditions with the issue of a special "Tomos" decree which brought it back to a normal status.

By the 1880s the "Anaplasis" ("Regeneration") Movement led to renewed spiritual energy and enlightenment. It fought against the rationalistic and materialistic ideas that had seeped in from secular Western Europe. It promoted catechism schools and Bible study circles.

Serbia

The Serbian Orthodox Church in thePrincipality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia ( sr-Cyrl, Књажество Србија, Knjažestvo Srbija) was an autonomous state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation wa ...

gained its autonomy in 1831, and was organized as the Metropolitanate of Belgrade

The Metropolitanate of Belgrade ( sr, Београдска митрополија, Beogradska mitropolija) was an Eastern Orthodox ecclesiastical province (metropolitanate) which existed between 1831 and 1920, with jurisdiction over the territo ...