Christianity in the 14th century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 14th century saw major developments in Christianity, including the Western Schism, the decline of the

The 14th century saw major developments in Christianity, including the Western Schism, the decline of the

King Philip IV of France created an inquisition for his suppression of the Knights Templar during the 14th century.Norman, ''The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History'' (2007), p. 93 King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed another in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), pp. 48-49 Over a 350-year period, this

King Philip IV of France created an inquisition for his suppression of the Knights Templar during the 14th century.Norman, ''The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History'' (2007), p. 93 King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed another in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), pp. 48-49 Over a 350-year period, this

In 1378 the conclave elected an Italian from Naples,

In 1378 the conclave elected an Italian from Naples,

*

*

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the bible, Matthew 6:6 and the

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the bible, Matthew 6:6 and the

Ecumenical Councils Eight and Nine

The island of Ruad, three kilometers from the Syrian shore, was occupied by the Knights Templar but was ultimately lost to the Mamluks in the Fall of Ruad on September 26, 1302. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which was not a crusader state and was not Latin Christian but was closely associated with the crusader states and was ruled by the Latin Christian Lusignan dynasty for its last 34 years, survived until 1375. Other echoes of the crusader states survived for longer, but well away from the Holy Land.

The island of Ruad, three kilometers from the Syrian shore, was occupied by the Knights Templar but was ultimately lost to the Mamluks in the Fall of Ruad on September 26, 1302. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which was not a crusader state and was not Latin Christian but was closely associated with the crusader states and was ruled by the Latin Christian Lusignan dynasty for its last 34 years, survived until 1375. Other echoes of the crusader states survived for longer, but well away from the Holy Land.

Tomas Baranauskas. ''Prūsų sukilimas—prarasta galimybė sukurti kitokią Lietuvą'' (Prussian rebellion—the lost chance of creating different Lithuania). 20 September, 2006

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. On April 16, 1346 (

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. On April 16, 1346 (

Schaff's ''The Seven Ecumenical Councils

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 14th Century Christianity by century, 14 Christianity in the Middle Ages, 14 14th-century Christianity,

The 14th century saw major developments in Christianity, including the Western Schism, the decline of the

The 14th century saw major developments in Christianity, including the Western Schism, the decline of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, and the appearance of precursors to Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

.

Inquisition

King Philip IV of France created an inquisition for his suppression of the Knights Templar during the 14th century.Norman, ''The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History'' (2007), p. 93 King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed another in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), pp. 48-49 Over a 350-year period, this

King Philip IV of France created an inquisition for his suppression of the Knights Templar during the 14th century.Norman, ''The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History'' (2007), p. 93 King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed another in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), pp. 48-49 Over a 350-year period, this Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people,Vidmar, ''The Catholic Church Through the Ages'' (2005), pp.150-152 representing around two percent of those accused.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), pp. 59, 203 The inquisition played a major role in the final expulsion of Islam from the kingdoms of Sicily and Spain.McManners, ''Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity'' (1990), p.187 In 1482, Pope Sixtus IV condemned its excesses but Ferdinand ignored his protests.Kamen, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (1997), p.49 Historians note that for centuries Protestant propaganda and popular literature exaggerated the horrors of these inquisitions.Armstrong, ''The European Reformation'' (2002), p. 103McManners, ''Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity'' (1990), p. 215Vidmar, ''The Catholic Church Through the Ages'' (2005), p. 146 According to Edward Norman, this view "identified the entire Catholic Church ... with heoccasional excesses" wrought by secular rulers.

Western Schism

TheWestern Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon b ...

, or Papal Schism, was a prolonged period of crisis in Latin Christendom from 1378 to 1416, when there were two or more claimants to the See of Rome and there was conflict concerning the rightful holder of the papacy. The conflict was political, rather than doctrinal, in nature.

To escape instability in Rome, Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon in southern FranceDuffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), p. 122 during a period known as the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon – at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire; now part of France – rather than in Rome. The situation a ...

. For 69 years popes resided in Avignon rather than Rome. This was not only an obvious source of not only confusion but of political animosity as the prestige and influence of the city of Rome waned without a resident pontiff. The papacy returned to Rome in 1378 at the urging of Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

and others who felt the See of Peter

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rom ...

should be in the Roman church.McManners, ''Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity'' (1990), p. 232, Chapter 6 Christian Civilization by Colin Morris (University of Southampton)Vidmar, ''The Catholic Church Through the Ages'' (2005), p. 155 Though Pope Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI ( la, Gregorius, born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pop ...

, a Frenchman, returned to Rome in 1378, the strife between Italian and French factions intensified, especially following his subsequent death.

In 1378 the conclave elected an Italian from Naples,

In 1378 the conclave elected an Italian from Naples, Pope Urban VI

Pope Urban VI ( la, Urbanus VI; it, Urbano VI; c. 1318 – 15 October 1389), born Bartolomeo Prignano (), was head of the Catholic Church from 8 April 1378 to his death in October 1389. He was the most recent pope to be elected from outside the ...

; his intransigence in office soon alienated the French cardinals, who withdrew to a conclave of their own, asserting the previous election was invalid since its decision had been made under the duress of a riotous mob. They elected one of their own, Robert of Geneva, who took the name Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

. By 1379, he was back in the palace of popes in Avignon, while Urban VI remained in Rome.

For nearly forty years, there were two papal curias and two sets of cardinals, each electing a new pope for Rome or Avignon when death created a vacancy. Efforts at resolution further complicated the issue when a third compromise pope was elected in 1409.McManners, ''Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity'' (1990), p. 240, Chapter 7 The Late Medieval Church and its Reformation by Patrick Collinson

Patrick "Pat" Collinson, (10 August 1929 – 28 September 2011) was an English historian, known as a writer on the Elizabethan era, particularly Elizabethan Puritanism. He was emeritus Regius Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge ...

(University of Cambridge) The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the cardinals called upon all three claimants to the papal throne to resign and held a new election naming Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

pope.

Western theology

Scholastic theology

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

continued to develop as the 13th century gave way to the fourteenth, becoming ever more complex and subtle in its distinctions and arguments. There was a rise to dominance of the nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings th ...

or voluntarist theologies of men like William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

. The 14th century was also a time in which movements of widely varying character worked for the reform of the institutional church, such as conciliarism

Conciliarism was a reform movement in the 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Catholic Church which held that supreme authority in the Church resided with an ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope.

The movement emerged in response to ...

, Lollardy

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholi ...

and the Hussite

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

s. Spiritual movements such as the Devotio Moderna

Devotio Moderna (Latin; lit., Modern Devotion) was a movement for religious reform, calling for apostolic renewal through the rediscovery of genuine pious practices such as humility, obedience, and simplicity of life. It began in the late 14th-cen ...

also flourished.

Notable authors include:

*

* Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

(1266-1308)

* Ramon Lull

Ramon Llull (; c. 1232 – c. 1315/16) was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'', conceived as a type of universal logic to pro ...

(1232-1315)

* Giles of Rome

Giles of Rome O.S.A. (Latin: ''Aegidius Romanus''; Italian: ''Egidio Colonna''; c. 1243 – 22 December 1316), was a Medieval philosopher and Scholastic theologian and a friar of the Order of St Augustine, who was also appointed to the ...

(1243-1316)

* Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

(1265-1321)

* Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim ( – ), commonly known as Meister Eckhart, Master Eckhart

(1275-1342)

* Nicholas of Lyra

Nicolas de Lyra

__notoc__

1479

Nicholas of Lyra (french: Nicolas de Lyre; – October 1349), or Nicolaus Lyranus, a Franciscan teacher, was among the most influential practitioners of biblical exegesis in the Middle Ages. Little is know ...

(1270-1349)

* Thomas Bradwardine (1290-1349)

* William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

(1287-1347)

* Richard Rolle (1290-1349)

* Gregory of Rimini

Gregory of Rimini (c. 1300 – November 1358), also called Gregorius de Arimino or Ariminensis, was one of the great scholastic philosophers and theologians of the Middle Ages. He was the first scholastic writer to unite the Oxonian and Parisia ...

(1300-1358)

* Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the wor ...

(1300-1358)

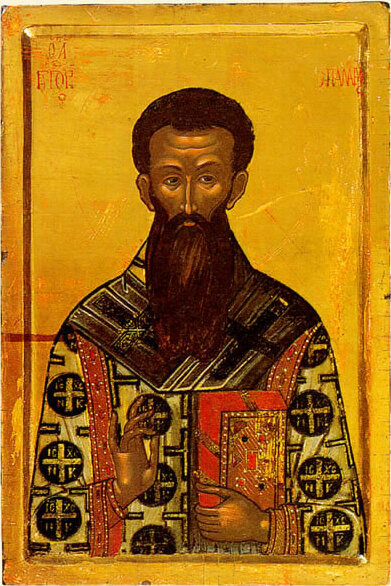

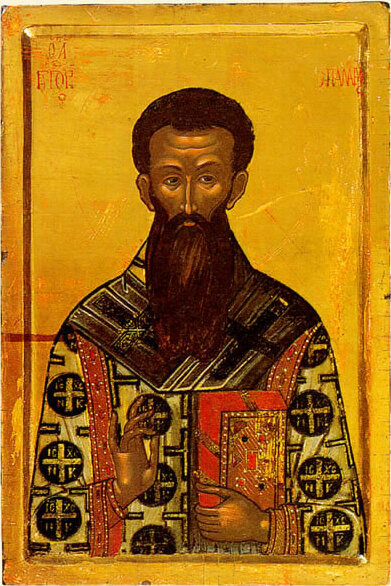

* Gregory Palamas

Gregory Palamas ( el, Γρηγόριος Παλαμᾶς; c. 1296 – 1359) was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos (modern Greece) and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, he ...

(1296-1359)

* Johannes Tauler

Johannes Tauler OP ( – 16 June 1361) was a German mystic, a Roman Catholic priest and a theologian. A disciple of Meister Eckhart, he belonged to the Dominican order. Tauler was known as one of the most important Rhineland mystics. He pro ...

(1300-1361)

* ''Theologia Germanica

''Theologia Germanica'', also known as ''Theologia Deutsch'' or ''Teutsch'', or as ''Der Franckforter'', is a mystical treatise believed to have been written in the later 14th century by an anonymous author. According to the introduction of the ...

'' (anonymous- but often attributed to Tauler)

* Henry Suso

Henry Suso, OP (also called Amandus, a name adopted in his writings, and Heinrich Seuse or Heinrich von Berg in German; 21 March 1295 – 25 January 1366) was a German Dominican friar and the most popular vernacular writer of the fourteenth cen ...

(1295-1366)

* John of Ruysbroeck

John van Ruysbroeck, original Flemish name Jan van Ruusbroec () (1293 or 1294 – 2 December 1381) was an Augustinian canon and one of the most important of the Flemish mystics. Some of his main literary works include ''The Kingdom of the Di ...

(1293-1381)

* Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; c. 1320–1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology an ...

(1320-1382)

* John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

(1320-1384)

* Geert Groote

Gerard Groote (October 1340 – 20 August 1384), otherwise ''Gerrit'' or ''Gerhard Groet'', in Latin ''Gerardus Magnus'', was a Dutch Catholic deacon, who was a popular preacher and the founder of the Brethren of the Common Life. He was a key fi ...

(1340-1384)

* Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (Italian: ''Caterina da Siena''; 25 March 1347 – 29 April 1380), a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, was a mystic, activist, and author who had a great influence on Italian literature and on the Catholic Church ...

(1347-1380)

* Walter Hilton

Walter Hilton Can.Reg. (c. 1340/1345 – 24 March 1396) was an English Augustinian mystic, whose works gained influence in 15th-century England and Wales. He has been canonized by the Church of England and by the Episcopal Church in the Unite ...

(1340-1396)

* ''The Cloud of Unknowing

''The Cloud of Unknowing'' (Middle English: ''The Cloude of Unknowyng'') is an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century. The text is a spiritual guide on contemplative prayer in the ...

'' (anonymous - but often attributed to Hilton)

* '' The Book of Privy Counseling'' (anonymous - but often attributed to Hilton)

* Julian of Norwich (1342-1416)

* John Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspi ...

(1369-1415)

Hesychast Controversy

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the bible, Matthew 6:6 and the

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the bible, Matthew 6:6 and the Philokalia

The ''Philokalia'' ( grc, φιλοκαλία, lit=love of the beautiful, from ''philia'' "love" and ''kallos'' "beauty") is "a collection of texts written between the 4th and 15th centuries by spiritual masters" of the mystical hesychast tr ...

. The tradition of contemplation with inner silence or tranquility is shared by all Eastern ascetics having its roots in the Egyptian traditions of monasticism exemplified by such Orthodox monastics as St Anthony of Egypt.

About the year 1337 Hesychasm attracted the attention of a learned member of the Orthodox Church, Barlaam, a Calabrian monk who at that time held the office of abbot in the Monastery of St Saviour's in Constantinople and who visited Mount Athos. Mount Athos was at the height of its fame and influence under the reign of Andronicus III Palaeologus

, image = Andronikos_III_Palaiologos.jpg

, caption = 14th-century miniature.Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek.

, succession = Byzantine emperor

, reign = 24 May 1328 – 15 June 1341

, coronation = ...

and under the 'first-ship' of the Protos Symeon. On Mount Athos, Barlaam encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices, also reading the writings of the teacher in Hesychasm of St Gregory Palamas

Gregory Palamas ( el, Γρηγόριος Παλαμᾶς; c. 1296 – 1359) was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos (modern Greece) and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, he ...

, an Athonite monk.

Trained in Western scholastic theology, Barlaam was scandalised by Hesychasm and began to combat it both orally and in his writings. As a private teacher of theology in the Western Scholastic mode, Barlaam propounded a more intellectual and propositional approach to the knowledge of God than the Hesychasts taught. Barlaam took exception to, as heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and blasphemous

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religio ...

, the doctrine entertained by the Hesychasts as to the nature of the uncreated light, the experience of which was said to be the goal of Hesychast practice. It was maintained by the Hesychasts to be of divine origin and to be identical to that light which had been manifested to Jesus' disciples on Mount Tabor

Mount Tabor ( he, הר תבור) (Har Tavor) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, west of the Sea of Galilee.

In the Hebrew Bible (Joshua, Judges), Mount Tabor is the site of the Battle of Mount Tabo ...

at the Transfiguration. This Barlaam held to be polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

, inasmuch as it postulated two eternal substances, a visible ( immanent) and an invisible God ( transcendent).

On the Hesychast side, the controversy was taken up by St Gregory Palamas

Gregory Palamas ( el, Γρηγόριος Παλαμᾶς; c. 1296 – 1359) was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos (modern Greece) and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, he ...

, afterwards Archbishop of Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, who was asked by his fellow monks on Mt Athos to defend Hesychasm from the Barlaam's attacks. St Gregory was well-educated in Greek philosophy ( dialectical method) and thus able to defend Hesychasm using Western precepts. In the 1340s, he defended Hesychasm at three different synods in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

and also wrote a number of works in its defense.

In 1341 the dispute came before a synod held at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

and was presided over by the Emperor Andronicus. The synod, taking into account the regard in which the writings of the pseudo-Dionysius

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite) was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the ''Corpus Areopagiticum' ...

were held, condemned Barlaam, who recanted and returned to Calabria, afterwards becoming a bishop in the Roman Catholic Church. One of Barlaam's friends, Gregory Akindynos

Gregory Akindynos ( Latinized as Gregorius Acindynus) ( el, ) (ca. 1300 – 1348) was a Byzantine theologian of Bulgarian origin.Ihor Ševčenko, Society and Intellectual Life in Late Byzantium, Vol. 137 of Collected Studies, Variorum Reprint, ...

, who originally was also a friend of St Gregory Palamas, took up the controversy, and three other synods on the subject were held, at the second of which the followers of Barlaam gained a brief victory. But in 1351 at a synod under the presidency of the Emperor John VI Cantacuzenus

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under And ...

, Hesychast doctrine and Palamas' Essence-Energies distinction was established as the doctrine of the Orthodox Church.

Following the decision of 1351, there was strong repression against anti-Palamist thinkers. Kalekas reports on this repression as late as 1397, and for theologians in disagreement with Palamas, there was ultimately no choice but to emigrate and convert to Catholicism, a path taken by Kalekas as well as Demetrios Kydones

Demetrios Kydones, Latinized as Demetrius Cydones or Demetrius Cydonius ( el, Δημήτριος Κυδώνης; 1324, Thessalonica – 1398, Crete), was a Byzantine Greek theologian, translator, author and influential statesman, who served an ...

and Ioannes Kypariossiotes. This exodus of highly educated Greek scholars, later reinforced by refugees following the Fall of Constantinople of 1453, had a significant influence on the first generation (that of Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

and Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was some ...

) of the incipient Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

.

The Roman Catholic Church has never fully accepted Hesychasm, especially the distinction between the energies or operations of God and the essence of God, and the notion that those energies or operations of God are uncreated. In Roman Catholic theology as it has developed since the scholastic period, the essence of God can be known but only in the next life; the grace of God is always created; and the essence of God is pure act, so that there can be no distinction between the energies or operations and the essence of God (see, e.g., the '' Summa Theologiae'' of St Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

). Some of these positions depend on Aristotelian metaphysics.

Contemporary historians Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under ...

and Nicephorus Gregoras

Nicephorus Gregoras (; Greek: , ''Nikephoros Gregoras''; c. 1295 – 1360) was a Greek astronomer, historian, and theologian.

Life

Gregoras was born at Heraclea Pontica, where he was raised and educated by his uncle, John, who was the Bisho ...

deal very copiously with this subject, taking the Hesychast and Barlaamite sides respectively. The Orthodox perspective is one that states that there is scientific knowledge based on demonstration and spiritual knowledge based on demonstration. That the two understandings must remain separate in order to have a proper understanding of both in order to reject dualism. The Eastern approach to understanding God and spiritual matters as one that should not be approached with a Scholastic and or dialectical method ( philosophy). Respected fathers of the church have held that these councils that agree that experiential prayer is Orthodox, refer to these as councils aEcumenical Councils Eight and Nine

Monasticism

Roman Catholic orders

Many distinct monastic orders developed within Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism. *Bridgettines

The Bridgettines, or Birgittines, formally known as the Order of the Most Holy Savior (; abbreviated OSsS), is a monastic religious order of the Catholic Church founded by Saint Birgitta or Bridget of Sweden in 1344, and approved by Pope Urba ...

, founded c.1350

* Hieronymites

The Hieronymites, also formally known as the Order of Saint Jerome ( la, Ordo Sancti Hieronymi; abbreviated OSH), is a Catholic cloistered religious order and a common name for several congregations of hermit monks living according to the Rule o ...

, founded in Spain in 1364, an eremitic

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Ch ...

community formally known as the "Order of Saint Jerome"

Protestant monasticism

Monasticism in theProtestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

tradition proceeds from John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

who organized the Lollard

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catho ...

Preacher Order (the "Poor Priests") to promote his reformation views.

Protestant Reformation precursors

Unrest because of the Western Schism excited wars between princes, uprisings among the peasants, and widespread concern over corruption in the Church. A newnationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

also challenged the relatively internationalist medieval world. The first of a series of disruptive and new perspectives came from John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, then from Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

at the University of Prague. The Catholic Church officially concluded this debate at the Council of Constance (1414–1417). The conclave condemned Jan Hus, who was executed by burning in spite of a promise of safe-conduct. At the command of Pope Martin V, Wycliffe was posthumously exhumed and burned as a heretic twelve years after his burial.

Crusade aftermath

The island of Ruad, three kilometers from the Syrian shore, was occupied by the Knights Templar but was ultimately lost to the Mamluks in the Fall of Ruad on September 26, 1302. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which was not a crusader state and was not Latin Christian but was closely associated with the crusader states and was ruled by the Latin Christian Lusignan dynasty for its last 34 years, survived until 1375. Other echoes of the crusader states survived for longer, but well away from the Holy Land.

The island of Ruad, three kilometers from the Syrian shore, was occupied by the Knights Templar but was ultimately lost to the Mamluks in the Fall of Ruad on September 26, 1302. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which was not a crusader state and was not Latin Christian but was closely associated with the crusader states and was ruled by the Latin Christian Lusignan dynasty for its last 34 years, survived until 1375. Other echoes of the crusader states survived for longer, but well away from the Holy Land.

Crusade against the Tatars

In the 14th century, KhanTokhtamysh

Tokhtamysh ( kz, Тоқтамыс, tt-Cyrl, Тухтамыш, translit=Tuqtamış, fa, توقتمش),The spelling of Tokhtamysh varies, but the most common spelling is Tokhtamysh. Tokhtamısh, Toqtamysh, ''Toqtamış'', ''Toqtamıs'', ''Toktamy ...

combined the Blue and White Hordes forming the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragme ...

. It seemed that the power of the Golden Horde had begun to rise, but in 1389, Tokhtamysh made the disastrous decision of waging war on his former master Tamerlane

Timur ; chg, ''Aqsaq Temür'', 'Timur the Lame') or as ''Sahib-i-Qiran'' ( 'Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction'), his epithet. ( chg, ''Temür'', 'Iron'; 9 April 133617–19 February 1405), later Timūr Gurkānī ( chg, ''Temür Kür ...

. Tamerlane's hordes rampaged through southern Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, crippling the Golden Horde's economy and practically wiping out its defenses in those lands.

After losing the war, Tokhtamysh was dethroned by the party of Khan Temur Kutlugh and Emir Edigu, supported by Tamerlane. When Tokhtamysh asked Vytautas the Great

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, Вітаўт, ''Vitaŭt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

for assistance in retaking the Horde, the latter readily gathered a huge army which included Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Russians, Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

s, Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

ns, Poles, Romanians and Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

.

In 1398, the huge army moved from Moldavia and conquered the southern steppe all the way to the Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

and northern Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. Inspired by their great successes, Vytautas declared a Crusade against the Tatars with Pope Boniface IX

Pope Boniface IX ( la, Bonifatius IX; it, Bonifacio IX; c. 1350 – 1 October 1404, born Pietro Tomacelli) was head of the Catholic Church from 2 November 1389 to his death in October 1404. He was the second Roman pope of the Western Schism.Rich ...

backing him. Thus, in 1399, the army of Vytautas once again moved on the Horde. His army met the Horde's at the Vorskla River

The Vorskla (; ) is a river that runs from Belgorod Oblast in Russia southwards into northeastern Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, w ...

, slightly inside Lithuanian territory.

Although the Lithuanian army was well equipped with cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

, it could not resist a rear attack from Edigu's reserve units. Vytautas hardly escaped alive. Many princes of his kin—possibly as many as 20—were killed, and the victorious Tatars besieged Kiev. Meanwhile, Temur Kutlugh died from the wounds received in the battle, and Tokhtamysh was killed by one of his own men.

Alexandrian Crusade

TheAlexandrian Crusade

The brief Alexandrian Crusade, also called the sack of Alexandria, occurred in October 1365 and was led by Peter I of Cyprus against Alexandria in Egypt. Although often referred to as and counted among the Crusades, it was relatively devoid of r ...

of October 1365 was a minor seaborne crusade against Muslim Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

led by Peter I of Cyprus

Peter I (9 October 1328 – 17 January 1369) was King of Cyprus and titular King of Jerusalem from his father's abdication on 24 November 1358 until his death in 1369. He was invested as titular Count of Tripoli in 1346. As King of Cyprus ...

. His motivation was at least as commercial as religious.

Politics and culture

The Crusades had an enormous influence on the EuropeanMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. At times, much of the continent was united under a powerful Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, but by the 14th century, the development of centralized bureaucracies (the foundation of the modern nation-state) was well on its way in France, England, Spain, Burgundy, and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, and partly because of the dominance of the church at the beginning of the crusading era.

The military experiences of the crusades also had their effects in Europe; for example, European castles became massive stone structures as they were in the east, rather than smaller wooden buildings as they had typically been in the past.

In addition, the Crusades are seen as having opened up European culture to the world, especially Asia:

Along with trade, new scientific discoveries and inventions made their way east or west. Persian advances (including the development of algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

, optics, and refinement of engineering) made their way west and sped the course of advancement in European universities that led to the Renaissance in later centuries

The invasions of German crusaders prevented formation of the large Lithuanian state incorporating all Baltic nations and tribes. Lithuania was destined to become a small country and forced to expand to the East looking for resources to combat the crusaders.Trade

The need to raise, transport and supply large armies led to a flourishing of trade throughout Europe. Roads largely unused since the days ofRome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

had significant increases in traffic as local merchants began to expand their horizons. This was not only because the Crusades prepared Europe for travel, but also because many wanted to travel after being reacquainted with the products of the Middle East. This also aided in the beginning of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

in Italy, as various Italian city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

from the very beginning had important and profitable trading colonies in the crusader states, both in the Holy Land and later in captured Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

territory.

Increased trade brought many things to Europeans that were once unknown or extremely rare and costly. These goods included a variety of spices, ivory, jade, diamonds, improved glass-manufacturing techniques, early forms of gunpowder, oranges, apples, and other Asian crops, and many other products.

Serbian Church

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. On April 16, 1346 (

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. On April 16, 1346 (Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

), King Stefan Dušan

Stefan Uroš IV Dušan ( sr-Cyrl, Стефан Урош IV Душан, ), known as Dušan the Mighty ( sr, / ; circa 1308 – 20 December 1355), was the King of Serbia from 8 September 1331 and Tsar (or Emperor) and autocrat of the Serbs, Gre ...

of Serbia convoked a grand assembly at Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and List of cities in North Macedonia by population, largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Sk ...

, attended by the Serbian Archbishop Joanikije II Joanikije ( sr-cyr, Јоаникије) is the Serbian variant of Greek name '' Ioannikios''. It may refer to:

*Joanikije I, Serbian Archbishop (1272–76)

* Joanikije II, Serbian Archbishop (1338–46) and first Serbian Patriarch (1346–54)

* Joa ...

, Archbishop Nicholas I of Ohrid

Nicholas I of Ohrid (Greek: Νικόλαος Α΄ Οχρίδας; Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serbian: Никола I Охридски) was Eastern Orthodox Archbishop of Ohrid, from c. 1340 to c. 1350.

In 1334, the Archbishopric of Ohrid came ...

, Patriarch Simeon of Bulgaria and various religious leaders of Mount Athos. The assembly and clergy agreed on, and then ceremonially performed the raising of the autocephalous Serbian Archbishopric to the status of Patriarchate. The Archbishop was from now on titled ''Serbian Patriarch''. The new Patriarch Joanikije II now solemnly crowned Stefan Dušan as "Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

and autocrat of Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

" (see Emperor of Serbs). The new Serbian Patriarchate took over supreme ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Mount Athos and many Greek eparchies in Aegean Macedonia

Aegean Macedonia ( mk, Егејска Македонија, translit=Egejska Makedonija'';'' bg, Егейска Македония, translit=Egeyska Makedonia) is a term describing the modern Greek region of Macedonia in Northern Greece. It is ...

that were until then under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The same process continued after the Serbian conquests of Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, Aetolia

Aetolia ( el, Αἰτωλία, Aἰtōlía) is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern regional unit of Aetolia-Acarnania.

Geography

The Achelous River separates Aetolia ...

and Acarnania in 1347 and 1348. In the same time, the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Ohrid Archbishopric remained autocephalous, recognizing the honorary primacy of the new Serbian Patriarchate.

Since proclamation of the Patriarchate was performed without consent of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, various canonical and political questions were raised. Supported by the Byzantine government, Ecumenical Patriarch Callistus I of Constantinople issued an act of condemnation and excommunication of Tsar Stefan Dušan and Serbian Patriarch Joanikije in 1350. That act created a rift between the Byzantine and Serbian churches, but not on dogmatic grounds, since the dispute was limited to the questions of ecclesiastical order and jurisdiction. Serbian Patriarch Joanikije died in 1354, and his successor Patriarch Sava IV (1354-1375) faced new challenges in 1371, when Turks defeated the Serbian army in the Battle of Marica and started their expansion into Serbian lands. Since they were facing the common enemy, the Serbian and Byzantine governments and church leaders reached an agreement in 1375. The act of excommunication was revoked and the Serbian Church was recognized as a Patriarchate, under the condition of returning all eparchies in contested southern regions to the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

After the new and decisive defeat by the Turks in the famous Battle of Kosovo in 1389, Serbia became a tributary state to the Ottoman Empire, and the Serbian Patriarchate was also affected by general social decline, since Ottoman Turks continued their expansion and raids into Serbian lands, devastating many monasteries and churches. The city of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and List of cities in North Macedonia by population, largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Sk ...

was taken by Turks in 1392, and all other southern regions were taken in 1395. That led to the gradual retreat of the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate in the south and expansion of the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid.

Spread of Christianity

Lithuania

Lithuania and Samogitia were ultimately Christianized from 1386 until 1417 by the initiative of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Jogaila and his cousin Vytautas.Timeline

See also

*History of Christianity *History of the Roman Catholic Church *History of the Eastern Orthodox Church *History of Christian theology#Late Scholasticism and its contemporaries *History of Oriental Orthodoxy *Christianization *Timeline of Christianity#Middle Ages *Timeline of Christian missions#Middle Ages *Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#800–1453 *Chronological list of saints and blesseds in the 14th centuryReferences

Works cited

* * * *Further reading

* Esler, Philip F. ''The Early Christian World''. Routledge (2004). . * Fletcher, Richard, ''The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD.'' London 1997. * Freedman, David Noel (Ed). ''Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible''. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (2000). . * Padberg, Lutz v., (1998): ''Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter'', Stuttgart, Reclam (German) * Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. ''The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600)''. University of Chicago Press (1975). .External links

Schaff's ''The Seven Ecumenical Councils

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 14th Century Christianity by century, 14 Christianity in the Middle Ages, 14 14th-century Christianity,