Christian theology is the

theology of

Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the

Old Testament and of the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

, as well as on

Christian tradition. Christian

theologians use biblical

exegesis,

rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an abi ...

analysis and argument. Theologians may undertake the study of Christian theology for a variety of reasons, such as in order to:

* help them better understand Christian tenets

* make

comparisons

Comparison or comparing is the act of evaluating two or more things by determining the relevant, comparable characteristics of each thing, and then determining which characteristics of each are similar to the other, which are different, and t ...

between Christianity and other traditions

*

defend Christianity against objections and criticism

* facilitate reforms in the Christian church

* assist in the

propagation of Christianity

* draw on the resources of the Christian tradition to address some present situation or perceived need

* education in

Christian philosophy, especially in

Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

philosophy

[Louth, Andrew. The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition: From Plato to Denys. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.]

Christian theology has permeated much of non-ecclesiastical

Western culture, especially in

pre-modern Europe, although

Christianity is a worldwide religion.

Theological spectrum

*

Conservative Christianity

*

Liberal Christianity

**

Progressive Christianity

*

Moderate Christianity

*

Christian nationalism

Christian traditions

Christian theology varies significantly across the main branches of Christian tradition:

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

,

Orthodox and

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. Each of those traditions has its own unique approaches to

seminaries

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

and ministerial formation.

Systematic theology

Systematic theology

Systematic theology, or systematics, is a discipline of Christian theology that formulates an orderly, rational, and coherent account of the doctrines of the Christian faith. It addresses issues such as what the Bible teaches about certain topic ...

as a discipline of Christian theology formulates an orderly, rational and coherent account of

Christian faith and beliefs. Systematic theology draws on the foundational

sacred texts of Christianity, while simultaneously investigating the development of Christian doctrine over the course of history, particularly through

philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

evolution. Inherent to a

system of theological thought is the development of a method, one which can apply both broadly and particularly. Christian systematic theology will typically explore:

*

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

(

theology proper)

* The

attributes of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

* The

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

as espoused by trinitarian Christians

*

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

*

Biblical hermeneutics

Biblical hermeneutics is the study of the principles of interpretation concerning the books of the Bible. It is part of the broader field of hermeneutics, which involves the study of principles of interpretation, both theory and methodology, for ...

– the interpretation of Biblical texts

* The

creation

*

Divine providence

*

Theodicy – accounting for a benign God's tolerance of evil

*

Philosophy

*

Hamartiology

In Christianity, sin is an immoral act considered to be a transgression of divine law. The doctrine of sin is central to the Christian faith, since its basic message is about redemption in Christ.

Hamartiology, a branch of Christian theolog ...

– the study of

sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

*

Christology – the study of the nature and person of Christ

*

Pneumatology – the study of the

Holy Spirit

*

Soteriology

Soteriology (; el, σωτηρία ' "salvation" from σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many religion ...

– the study of

salvation

*

Ecclesiology

In Christian theology, ecclesiology is the study of the Church (congregation), Church, the origins of Christianity, its relationship to Jesus, its role in salvation, its ecclesiastical polity, polity, its Church discipline, discipline, its escha ...

– the study of the Christian church

*

Missiology

Missiology is the academic study of the Christian mission history and methodology, which began to be developed as an academic discipline in the 19th century.

History

Missiology as an academic discipline appeared only in the 19th century. It was ...

– the study of the Christian message and of missions

*

Spirituality and

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ...

*

Sacramental theology

*

Eschatology – the ultimate destiny of humankind

*

Moral theology

Ethics involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior.''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''"Ethics"/ref> A central aspect of ethics is "the good life", the life worth living or life that is simply sati ...

*

Christian anthropology

* The

afterlife

Prolegomena: Scripture as a primary basis of Christian theology

Biblical revelation

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

is the revealing or disclosing, or making something obvious through active or passive communication with God, and can originate directly from

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

or through an agent, such as an

angel. A person recognised as having experienced such contact is often called a

prophet. Christianity generally considers the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

as divinely or

supernaturally revealed or inspired. Such revelation does not always require the presence of God or an angel. For instance, in the concept which

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

s call

interior locution

An interior locution is a mystical concept used by various religions. An interior locution is a form of private revelation, but is distinct from an apparition, or religious vision. An interior locution may be defined as "A supernatural communicat ...

, supernatural revelation can include just an

inner voice heard by the recipient.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) first described two types of revelation in Christianity:

general revelation and

special revelation.

* General revelation occurs through observation of the

created order. Such observations can logically lead to important conclusions, such as the existence of God and some of God's attributes. General revelation is also an element of

Christian apologetics

Christian apologetics ( grc, ἀπολογία, "verbal defense, speech in defense") is a branch of Christian theology that defends Christianity.

Christian apologetics has taken many forms over the centuries, starting with Paul the Apostle in ...

.

* Certain specifics, such as the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

and the

Incarnation, as revealed in the teachings of the Scriptures, can not otherwise be deduced except by special revelation.

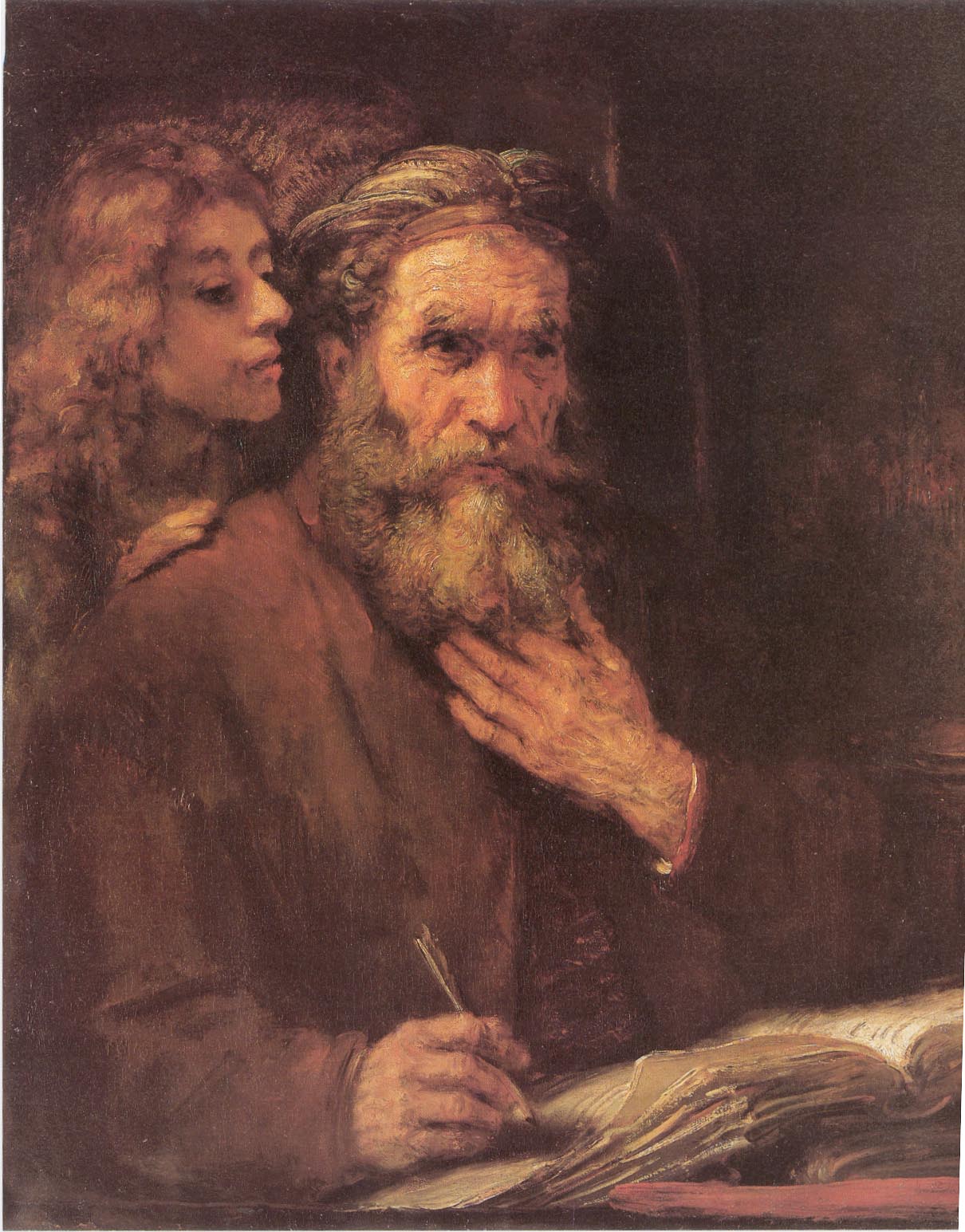

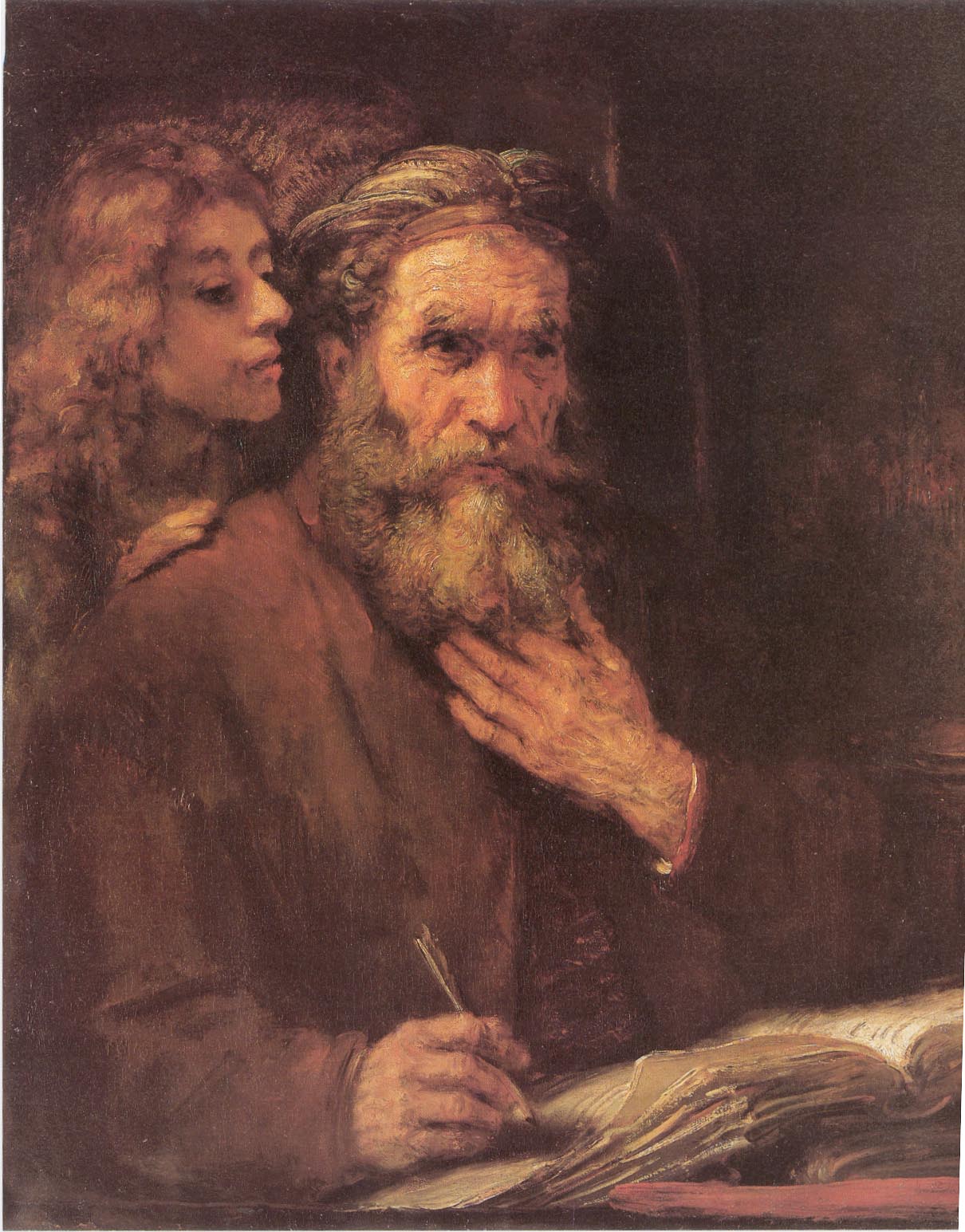

Biblical inspiration

The

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

contains many passages in which the authors claim divine inspiration for their message or report the effects of such inspiration on others. Besides the direct accounts of written

revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

(such as

Moses receiving the

Ten Commandments inscribed on tablets of stone), the

Prophets of the

Old Testament frequently claimed that their message was of divine origin by prefacing the revelation using the following phrase: "Thus says the LORD" (for example

1 Kgs 12:22–24;1 Chr 17:3–4; Jer 35:13; Ezek 2:4; Zech 7:9 etc.). The

Second Epistle of Peter claims that "no prophecy of Scripture ... was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit" The Second Epistle of Peter also implies that Paul's writings are inspired

2 Pet 3:16.

Many Christians cite a verse in Paul's letter to Timothy, 2 Timothy 3:16–17, as evidence that "all scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable ..." Here St. Paul is referring to the Old Testament, since the scriptures have been known by Timothy from "infancy" (verse 15). Others offer an alternative reading for the passage; for example, theologian

C. H. Dodd suggests that it "is probably to be rendered" as: "Every inspired scripture is also useful..."

A similar translation appears in the

New English Bible

The New English Bible (NEB) is an English translation of the Bible. The New Testament was published in 1961 and the Old Testament (with the Apocrypha) was published on 16 March 1970. In 1989, it was significantly revised and republished as the R ...

, in the

Revised English Bible

The Revised English Bible (REB) is a 1989 English-language translation of the Bible that updates the New English Bible (NEB) of 1970. As with its predecessor, it is published by the publishing houses of both the universities of Oxford and Cambri ...

, and (as a footnoted alternative) in the

New Revised Standard Version. The Latin

Vulgate can be so read. Yet others defend the "traditional" interpretation;

Daniel B. Wallace

Daniel Baird Wallace (born June 5, 1952) is an American professor of New Testament Studies at Dallas Theological Seminary. He is also the founder and executive director of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, the purpose of whi ...

calls the alternative "probably not the best translation."

Some modern English versions of the Bible renders ''theopneustos'' with "God-breathed" (

NIV) or "breathed out by God" (

ESV), avoiding the word ''inspiration'', which has the Latin root ''inspīrāre'' - "to blow or breathe into".

Biblical authority

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

generally regards the

agreed collections of books known as the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

as authoritative and as written by human authors under the inspiration of the

Holy Spirit. Some Christians believe that the Bible is

inerrant (totally without error and free from contradiction, including the historical and scientific parts)

or

infallible (inerrant on issues of faith and practice but not necessarily on matters of history or science).

[

]

Some Christians infer that the Bible cannot both refer to itself as being divinely inspired and also be errant or fallible. For if the Bible were divinely inspired, then the source of inspiration being divine, would not be subject to fallibility or error in that which is produced. For them, the doctrines of the divine inspiration, infallibility, and inerrancy, are inseparably tied together. The idea of biblical

integrity

Integrity is the practice of being honest and showing a consistent and uncompromising adherence to strong moral and ethical principles and values.

In ethics, integrity is regarded as the honesty and truthfulness or accuracy of one's actions. In ...

is a further concept of infallibility, by suggesting that current biblical text is complete and without error, and that the integrity of biblical text has never been corrupted or degraded.

Historians note, or claim, that the doctrine of the Bible's infallibility was adopted hundreds of years after the books of the Bible were written.

Biblical canon

The content of the

Protestant Old Testament is the same as the

Hebrew Bible canon, with changes in the division and order of books, but the

Catholic Old Testament contains additional texts, known as the

deuterocanonical books

The deuterocanonical books (from the Greek meaning "belonging to the second canon") are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Assyrian Church of the East to be ...

. Protestants recognize 39 books in their Old Testament canon, while Roman Catholic and

Eastern Christians recognize 46 books as canonical. Both Catholics and Protestants use the same 27-book New Testament canon.

Early Christians used the

Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond ...

, a

Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures. Christianity subsequently endorsed various additional writings that would become the New Testament. In the 4th century a series of

synods, most notably the

Synod of Hippo in AD 393, produced a list of texts equal to the 46-book canon of the Old Testament that Catholics use today (and the 27-book canon of the New Testament that all use). A definitive list did not come from any

early ecumenical council. Around 400,

Jerome produced the

Vulgate, a definitive Latin edition of the Bible, the contents of which, at the insistence of the

Bishop of Rome, accorded with the decisions of the earlier synods. This process effectively set the New Testament canon, although examples exist of other canonical lists in use after this time.

During the 16th-century

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

certain reformers proposed different canonical lists of the Old Testament. The texts which appear in the Septuagint but not in the Jewish canon fell out of favor, and eventually disappeared from Protestant canons. Catholic Bibles classify these texts as deuterocanonical books, whereas Protestant contexts label them as the

Apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

.

Theology proper: God

In

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, God is the

creator and preserver of the universe. God is the

sole ultimate power in the universe but is distinct from it. The

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

never speaks of God as impersonal. Instead, it refers to him in

personal terms– who speaks, sees, hears, acts, and loves. God is understood to have a

will and personality and is an

all powerful,

divine and

benevolent being. He is represented in

Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

as being primarily concerned with people and their salvation.

Attributes of God

Classification

Many

Reformed theologians distinguish between the ''communicable'' attributes (those that human beings can also have) and the ''incommunicable'' attributes (those which belong to God alone).

Enumeration

Some attributes ascribed to God in Christian theology are:

*

Aseity

Aseity (from Latin ''ā'' "from" and ''sē'' "self", plus '' -ity'') is the property by which a being exists of and from itself. It refers to the Christian belief that God does not depend on any cause other than himself for his existence, realiza ...

—That "God is so independent that he does not need us." It is based on

Acts

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

17:25, where it says that God "is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything" (

NIV). This is often related to God's ''self-existence'' and his ''self-sufficiency''.

*

Eternity

Eternity, in common parlance, means infinite time that never ends or the quality, condition, or fact of being everlasting or eternal. Classical philosophy, however, defines eternity as what is timeless or exists outside time, whereas sempit ...

—That God exists beyond the

temporal realm.

*

Graciousness—That God extends His favor and gifts to human beings unconditionally as well as conditionally.

*

Holiness

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

—That God is separate from sin and incorruptible. Noting the refrain of "

Holy, holy, holy" in

Isaiah 6:3 and

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

4:8,

*

Immanence—That although God is

transcendent and holy, He is also accessible and can be dynamically experienced.

*

Immutability

In object-oriented and functional programming, an immutable object (unchangeable object) is an object whose state cannot be modified after it is created.Goetz et al. ''Java Concurrency in Practice''. Addison Wesley Professional, 2006, Section 3.4 ...

—That God's essential nature is unchangeable.

*

Impassibility—That God does not experience emotion or suffering (a more controversial doctrine, disputed especially by

open theism).

*

Impeccability

Impeccability is the absence of sin. Christianity teaches this to be an attribute of God (logically God cannot sin: it would mean that he would act against his own will and nature) and therefore it is also attributed to Christ.

Roman Catholic ...

—That God is incapable of error (

sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

).

*

Incorporeality

Incorporeality is "the state or quality of being incorporeal or bodiless; immateriality; incorporealism." Incorporeal (Greek: ἀσώματος) means "Not composed of matter; having no material existence."

Incorporeality is a quality of souls, ...

—That God is without physical composition. A related concept is the ''

spirituality'' of God, which is derived from

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

' statement in

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

4:24, "God is spirit."

*

Love—That God is care and compassion.

1 John 4:16 says "God is love."

*

Mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

—That God is the supreme liberator. While the

Mission of God is not traditionally included in this list,

David Bosch

David Jacobus Bosch (13 December 1929 – 15 April 1992) was an influential missiologist and theologian best known for his book ''Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission'' (1991) — a major work on post-colonial C ...

has argued that "

mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

is not primarily an activity of the church, but an attribute of God."

*

Omnibenevolence

Omnibenevolence (from Latin ''omni-'' meaning "all", ''bene-'' meaning "good" and ''volens'' meaning "willing") is defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' as "unlimited or infinite benevolence". Some philosophers have argued that it is impos ...

—That God is omnibenevolent.

Omnibenevolence

Omnibenevolence (from Latin ''omni-'' meaning "all", ''bene-'' meaning "good" and ''volens'' meaning "willing") is defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' as "unlimited or infinite benevolence". Some philosophers have argued that it is impos ...

of God refers to him being "all good".

*

Omnipotence

Omnipotence is the quality of having unlimited power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as one ...

—That God is supremely or all-powerful.

*

Omnipresence—That God is the supreme being, existing everywhere and at all times; the all-perceiving or all-conceiving foundation of reality.

*

Omniscience—That God is supremely or all-knowing.

*Oneness—That God is without peer, also that every divine attribute is instantiated in its entirety (the qualitative

infinity of God). See also

Monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfo ...

and

Divine simplicity.

*

Providence—That God watches over His creation with interest and dedication. While the

Providence of God usually refers to his activity in the world, it also implies his care for the universe, and is thus an attribute. A distinction is usually made between "general providence" which refers to God's continuous upholding the existence and natural order of the universe, and "special providence" which refers to God's extraordinary intervention in the life of people. See also

Sovereignty.

*

Righteousness

Righteousness is the quality or state of being morally correct and justifiable. It can be considered synonymous with "rightness" or being "upright". It can be found in Indian religions and Abrahamic traditions, among other religions, as a theologi ...

—That God is the greatest or only measure of human conduct. The righteousness of God may refer to his holiness, to his

justice, or to his saving activity through Christ.

*

Transcendence—That God exists beyond the natural realm of physical laws and thus is not bound by them; He is also wholly

Other

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

and

incomprehensible apart from

general or

special self-revelation.

*

Triune—The Christian God is understood (by trinitarian Christians) to be a "threeness" of

Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

,

Son, and

Holy Spirit that is fully consistent with His "oneness"; a single infinite being who is both within and beyond nature. Because the persons of the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

represent a personal relation even on the level of God to Himself, He is personal both in His relation toward us and in His relation toward Himself.

*

Veracity—That God is the Truth all human beings strive for; He is also impeccably honest.

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

1:2 refers to "God, who does not lie."

*

Wisdom

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowle ...

—That God fully comprehends

human nature and the world, and will see His will accomplished in heaven and on earth.

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

16:27 speaks about the "only wise God".

Monotheism

Some Christians believe that the God worshiped by the Hebrew people of the pre-Christian era had always revealed himself as he did through

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

; but that this was never obvious until Jesus was born (see

John 1

John 1 is the first chapter in the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Holy Bible. The author of the book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that John composed this gospel.Holman Illust ...

). Also, though the

Angel of the Lord

The (or an) angel of the ( he, מַלְאַךְ יְהוָה '' mal’āḵ YHWH'' "messenger of Yahweh") is an entity appearing repeatedly in the Tanakh (Old Testament) on behalf of the God of Israel.

The guessed term ''YHWH'', which occurs ...

spoke to the Patriarchs, revealing God to them, some believe it has always been only through the

Spirit of God granting them understanding, that men have been able to perceive later that God himself had visited them.

This belief gradually developed into the modern formulation of the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, which is the doctrine that God is a single entity (

Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he poss ...

), but that there is a trinity in God's single being, the meaning of which has always been debated. This mysterious "Trinity" has been described as

hypostases in the

Greek language

Greek ( el, label= Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy ( Calabria and Salento), southe ...

(

subsistences in

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

), and "persons" in English. Nonetheless, Christians stress that they only believe in one God.

Most Christian churches teach the Trinity, as opposed to Unitarian monotheistic beliefs. Historically, most Christian churches have taught that the nature of God is a

mystery

Mystery, The Mystery, Mysteries or The Mysteries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional characters

*Mystery, a cat character in ''Emily the Strange''

Films

* ''Mystery'' (2012 film), a 2012 Chinese drama film

* ''Mystery'' ( ...

, something that must be revealed by

special revelation rather than deduced through

general revelation.

Christian orthodox traditions (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant) follow this idea, which was codified in 381 and reached its full development through the work of the

Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocian Fathers, also traditionally known as the Three Cappadocians, are Basil the Great (330–379), who was bishop of Caesarea; Basil's younger brother Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 395), who was bishop of Nyssa; and a close friend ...

. They consider God to be a

triune entity, called the Trinity, comprising the three "Persons";

God the Father,

God the Son, and

God the Holy Spirit, described as being "of the same substance" (). The true nature of an infinite God, however, is commonly described as beyond definition, and the word 'person' is an imperfect expression of the idea.

Some critics contend that because of the adoption of a tripartite conception of deity, Christianity is a form of

tritheism or

polytheism. This concept dates from

Arian teachings which claimed that Jesus, having appeared later in the Bible than his Father, had to be a secondary, lesser, and therefore distinct god. For

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, the idea of God as a trinity is

heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

– it is considered akin to

polytheism. Christians overwhelmingly assert that monotheism is central to the Christian faith, as the very

Nicene Creed (among others) which gives the orthodox Christian definition of the Trinity does begin with: "I believe in one God".

In the 3rd century,

Tertullian claimed that God exists as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit—the three personae of one and the same substance.

[''Critical Terms for Religious Studies.'' Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998. ''Credo Reference''. 27 July 2009] To trinitarian Christians God the Father is not at all a separate god from God the Son (of whom

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

is the incarnation) and the Holy Spirit, the other ''

hypostases'' (Persons) of the

Christian Godhead.

[ According to the Nicene Creed, the Son (Jesus Christ) is "eternally begotten of the Father", indicating that their divine Father-Son relationship is not tied to an event within time or human history.

In ]Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, the doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

of the Trinity states that God is one being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a mutual indwelling of three Persons: the Father, the Son (incarnate as Jesus), and the Holy Spirit (or Holy Ghost). Since earliest Christianity, one's salvation has been very closely related to the concept of a triune God, although the Trinitarian doctrine was not formalized until the 4th century. At that time, the Emperor Constantine

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterrane ...

convoked the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

, to which all bishops of the empire were invited to attend. Pope Sylvester I did not attend but sent his legate. The council, among other things, decreed the original Nicene Creed.

Trinity

For most Christians, beliefs about God are enshrined in the doctrine of

For most Christians, beliefs about God are enshrined in the doctrine of Trinitarianism

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, which holds that the three persons of God together form a single God. The Trinitarian view emphasizes that God has a will and that God the Son has two wills, divine and human, though these are never in conflict (see Hypostatic union). However, this point is disputed by Oriental Orthodox Christians, who hold that ''God the Son'' has only one will of unified divinity and humanity (see Miaphysitism).

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity teaches the unity of Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

, Son, and Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead.[Encyclopædia Britannica: Purgatory in world religions:](_blank)

"The idea of purification or temporary punishment after death has ancient roots and is well-attested in early Christian literature. The conception of purgatory as a geographically situated place is largely the achievement of medieval Christian piety and imagination." The doctrine states that God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

is the Triune God, existing as three ''persons'', or in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

'' hypostases'', but one being. Personhood in the Trinity does not match the common Western understanding of "person" as used in the English language—it does not imply an "individual, self-actualized center of free will and conscious activity."[ Each ''person'' is understood as having the one identical essence or nature, not merely similar natures. Since the beginning of the ]3rd century

The 3rd century was the period from 201 ( CCI) to 300 ( CCC) Anno Domini (AD) or Common Era (CE) in the Julian calendar..

In this century, the Roman Empire saw a crisis, starting with the assassination of the Roman Emperor Severus Alexande ...

the doctrine of the Trinity has been stated as "the one God exists in three Persons and one substance, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit."Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Oriental Orthodoxy as well as other prominent Christian sects arising from the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, such as Anglicanism, Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's br ...

, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

, Baptist, and Presbyterianism. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' describes the Trinity as "the central dogma of Christian theology".Nontrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essenc ...

positions which include Unitarianism, Oneness

Oneness may refer to:

Economy

* Law of one price (LoP), an economic concept which posits that "a good must sell for the same price in all locations".

Religious philosophy

* Oneness Pentecostalism, a movement of nontrinitarian denominations

* Nond ...

and Modalism

Modalistic Monarchianism, also known as Modalism or Oneness Christology, is a Christian theology upholding the oneness of God as well as the divinity of Jesus; as a form of Monarchianism, it stands in contrast with Trinitarianism. Modalistic Monar ...

. A small minority of Christians hold non-trinitarian views, largely coming under the heading of Unitarianism.

Most, if not all, Christians believe that God is spirit, an uncreated, omnipotent, and eternal being, the creator and sustainer of all things, who works the redemption of the world through his Son, Jesus Christ. With this background, belief in the divinity of Christ

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

and the Holy Spirit is expressed as the doctrine of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, which describes the single divine '' ousia'' (substance) existing as three distinct and inseparable ''hypostases'' (persons): the Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

, the Son (Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

the Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

), and the Holy Spirit.

The Trinitarian doctrine is considered by most Christians to be a core tenet of their faith. Nontrinitarians

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

typically hold that God, the Father, is supreme; that Jesus, although still divine Lord and Savior, is the Son of God; and that the Holy Spirit is a phenomenon akin to God's will on Earth. The holy three are separate, yet the Son and the Holy Spirit are still seen as originating from God the Father.

The New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

does not have the term "Trinity" and nowhere discusses the Trinity as such. Some emphasize, however, that the New Testament does repeatedly speak of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit to "compel a trinitarian understanding of God."

God the Father

In many monotheist

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

religions, God is addressed as the father, in part because of his active interest in human affairs, in the way that a father would take an interest in his children who are dependent on him and as a father, he will respond to humanity, his children, acting in their best interests. In Christianity, God is called "Father" in a more literal sense, besides being the creator and nurturer of creation, and the provider for his children. The Father is said to be in unique relationship with his only begotten (''monogenes'') son, Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, which implies an exclusive and intimate familiarity: "No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and any one to whom the Son chooses to reveal him."

In Christianity, God the Father's relationship with humanity is as a father to children—in a previously unheard-of sense—and not just as the creator and nurturer of creation, and the provider for his children, his people. Thus, humans, in general, are sometimes called ''children of God''. To Christians, God the Father's relationship with humanity is that of Creator and created beings, and in that respect he is the father of all. The New Testament says, in this sense, that the very idea of family, wherever it appears, derives its name from God the Father, and thus God himself is the model of the family.

However, there is a deeper "legal" sense in which Christians believe that they are made participants in the special relationship of Father and Son, through Jesus Christ as his spiritual bride

A bride is a woman who is about to be married or who is newlywed.

When marrying, the bride's future spouse, (if male) is usually referred to as the '' bridegroom'' or just ''groom''. In Western culture, a bride may be attended by a maid, bri ...

. Christians call themselves ''adopted'' children of God.

In the New Testament, God the Father has a special role in his relationship with the person of the Son, where Jesus is believed to be his Son and his heir.. According to the Nicene Creed, the Son (Jesus Christ) is "eternally begotten of the Father", indicating that their divine Father-Son relationship is not tied to an event within time or human history. ''See'' Christology. The Bible refers to Christ, called " The Word" as present at the beginning of God's creation., not a creation himself, but equal in the personhood of the Trinity.

In Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

theology, God the Father is the "principium" (''beginning''), the "source" or "origin" of both the Son and the Holy Spirit, which gives intuitive emphasis to the threeness of persons; by comparison, Western theology explains the "origin" of all three ''hypostases'' or persons as being in the divine nature, which gives intuitive emphasis to the oneness

Oneness may refer to:

Economy

* Law of one price (LoP), an economic concept which posits that "a good must sell for the same price in all locations".

Religious philosophy

* Oneness Pentecostalism, a movement of nontrinitarian denominations

* Nond ...

of God's being.

Christology and Christ

Christology is the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the nature, person, and works of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, held by Christians to be the Son of God. Christology is concerned with the meeting of the human ( Son of Man) and divine ( God the Son or Word of God) in the person of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

.

Primary considerations include the Incarnation, the relationship of Jesus' nature and person with the nature and person of God, and the salvific work of Jesus. As such, Christology is generally less concerned with the details of Jesus' life (what he did) or teaching than with who or what he is. There have been and are various perspectives by those who claim to be his followers since the church began after his ascension. The controversies ultimately focused on whether and how a human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

nature and a divine nature can co-exist in one person. The study of the inter-relationship of these two natures is one of the preoccupations of the majority tradition.

Teachings about Jesus and testimonies about what he accomplished during his three-year public ministry are found throughout the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

. Core biblical teachings about the person of Jesus Christ may be summarized that Jesus Christ was and forever is fully God (divine) and fully human in one sinless person at the same time,resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lo ...

, sinful

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life via his New Covenant

The New Covenant (Hebrew '; Greek ''diatheke kaine'') is a biblical interpretation which was originally derived from a phrase which is contained in the Book of Jeremiah ( Jeremiah 31:31-34), in the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament of the ...

. While there have been theological disputes over the nature of Jesus, Christians believe that Jesus is God incarnate and " true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human in all respects, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, yet he did not sin. As fully God, he defeated death and rose to life again. Scripture asserts that Jesus was conceived, by the Holy Spirit, and born of his virgin mother Mary without a human father. The biblical accounts of Jesus' ministry include miracles

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divin ...

, preaching, teaching, healing, Death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

, and resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, whic ...

. The apostle Peter, in what has become a famous proclamation of faith among Christians since the 1st century, said, "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God." Most Christians now wait for the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messian ...

of Christ when they believe he will fulfill the remaining Messianic prophecies

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' i ...

.

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(''Khristós'') meaning " the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

(''Māšîaḥ''), usually transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus ''trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → , Cyrillic → , Greek → the digraph , Armenian → or L ...

into English as '' Messiah''. The word is often misunderstood to be the surname of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

due to the numerous mentions of ''Jesus Christ'' in the Christian Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

. The word is in fact used as a title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

, hence its common reciprocal use ''Christ Jesus'', meaning Jesus the Anointed One or Jesus the Messiah. Followers of Jesus became known as Christians because they believed that Jesus was the Christ, or Messiah, prophesied about in the Old Testament, or Tanakh.

Trinitarian ecumenical councils

The Christological controversies came to a head over the persons of the Godhead and their relationship with one another.

Christology was a fundamental concern from the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

(325) until the Third Council of Constantinople (680). In this time period, the Christological views of various groups within the broader Christian community led to accusations of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, and, infrequently, subsequent religious persecution. In some cases, a sect's unique Christology is its chief distinctive feature, in these cases it is common for the sect to be known by the name given to its Christology.

The decisions made at First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

and re-ratified at the First Council of Constantinople

The First Council of Constantinople ( la, Concilium Constantinopolitanum; grc-gre, Σύνοδος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 b ...

, after several decades of ongoing controversy during which the work of Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocian Fathers, also traditionally known as the Three Cappadocians, are Basil the Great (330–379), who was bishop of Caesarea; Basil's younger brother Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 395), who was bishop of Nyssa; and a close friend ...

were influential. The language used was that the one God exists in three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit); in particular it was affirmed that the Son was '' homoousios'' (of one substance) with the Father. The Creed of the Nicene Council made statements about the full divinity and full humanity of Jesus, thus preparing the way for discussion about how exactly the divine and human come together in the person of Christ (Christology).

Nicaea insisted that Jesus was fully divine and also human. What it did not do was make clear how one person could be both divine and human, and how the divine and human were related within that one person. This led to the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries of the Christian era.

The Chalcedonian Creed

The Chalcedonian Definition (also called the Chalcedonian Creed or the Definition of Chalcedon) is a declaration of Christ's nature (that it is dyophysite), adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. Chalcedon was an early centre of Christ ...

did not put an end to all Christological debate, but it did clarify the terms used and became a point of reference for all other Christologies. Most of the major branches of Christianity—Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Eastern Orthodoxy, Anglicanism, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

, and Reformed—subscribe to the Chalcedonian Christological formulation, while many branches of Eastern Christianity— Syrian Orthodoxy, Assyrian Church Assyrian Church may refer to:

* Chaldean Catholic Church, an Eastern Christian church founded by and composed of ethnic Assyrians entered into communion with Rome.

* Assyrian Church of the East, an Eastern Christian church.

* Ancient Church of the ...

, Coptic Orthodoxy

The Coptic Orthodox Church ( cop, Ϯⲉⲕ̀ⲕⲗⲏⲥⲓⲁ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲣⲑⲟⲇⲟⲝⲟⲥ, translit=Ti.eklyseya en.remenkimi en.orthodoxos, lit=the Egyptian Orthodox Church; ar, الكنيسة القبطي� ...

, Ethiopian Orthodox

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

y, and Armenian Apostolicism—reject it.

Attributes of Christ

=God as Son

=

According to the Bible, the second Person of the Trinity, because of his eternal relation to the first Person (God as Father), is the Son of God. He is considered (by Trinitarians) to be coequal with the Father and Holy Spirit. He is all God and all human: the Son of God as to his divine nature, while as to his human nature he is from the lineage of David. The core of Jesus' self-interpretation was his "filial consciousness", his relationship to God as child to parent in some unique sense[Stagg, Frank. ''New Testament Theology'', Nashville: Broadman, 1962.] (see Filioque controversy). His mission on earth proved to be that of enabling people to know God as their Father, which Christians believe is the essence of eternal life.

God the Son is the second person of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

in Christian theology. The doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

of the Trinity identifies Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

of Nazareth as God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

the Son, ''united in essence but distinct in person'' with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit (the first and third persons of the Trinity). God the Son is co-eternal with God the Father (and the Holy Spirit), both before Creation and after the End (see Eschatology). So Jesus was always "God the Son", though not revealed as such until he also became ''the'' "Son of God" through incarnation. "Son of God" draws attention to his humanity, whereas "God the Son" refers more generally to his divinity, including his pre-incarnate existence. So, in Christian theology, Jesus was always God the Son, though not revealed as such until he also became the Son of God through incarnation.

The exact phrase "God the Son" is not in the New Testament. Later theological use of this expression reflects what came to be standard interpretation of New Testament references, understood to imply Jesus' divinity, but the distinction of his person from that of the one God he called his Father. As such, the title is associated more with the development of the doctrine of the Trinity than with the Christological

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Di ...

debates. There are over 40 places in the New Testament where Jesus is given the title "the Son of God", but scholars don't consider this to be an equivalent expression. "God the Son" is rejected by anti-trinitarians, who view this reversal of the most common term for Christ as a doctrinal perversion and as tending towards tritheism.

Matthew cites Jesus as saying, "Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called sons of God (5:9)." The gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

s go on to document a great deal of controversy over Jesus being ''the'' Son of God, in a unique way. The book of the Acts of the Apostles and the letters of the New Testament, however, record the early teaching of the first Christians– those who believed Jesus to be ''both'' the Son of God, the Messiah, a man appointed by God, as well as God himself. This is evident in many places, however, the early part of the book of Hebrews addresses the issue in a deliberate, sustained argument, citing the scriptures of the Hebrew Bible as authorities. For example, the author quotes Psalm 45:6 as addressed by the God of Israel to Jesus.

* Hebrews 1:8. About the Son he says, "Your throne, O God, will last for ever and ever."

The author of Hebrews' description of Jesus as the exact representation of the divine Father has parallels in a passage in Colossians

The Epistle to the Colossians is the twelfth book of the New Testament. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately f ...

.

*Colossians 2:9–10. "in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form"

John's gospel quotes Jesus at length regarding his relationship with his heavenly Father. It also contains two famous attributions of divinity to Jesus.

*John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

1:1. "the Word was God" n_context,_the_''Word''_is_Jesus,_see_ n_context,_the_''Word''_is_Jesus,_see_Christ_the_Logos">Christ_the_Logos.html"_;"title="n_context,_the_''Word''_is_Jesus,_see_Christ_the_Logos">n_context,_the_''Word''_is_Jesus,_see_Christ_the_Logos*John_

John_is_a_common_English_name_and_surname:

*_John_(given_name)

*__John_(surname)

John_may_also_refer_to:

__New_Testament_

__Works_

*_Gospel_of_John,_a_title_often_shortened_to_John

*__First_Epistle_of_John,_often_shortened_to_1_John

*__Secon_...

_20:28._"Thomas_said_to_him,_'My_Lord_and_my_God!'"

The_most_direct_references_to_Jesus_as_God_are_found_in_various_letters.

*

The

The  Some Christians believe that the God worshiped by the Hebrew people of the pre-Christian era had always revealed himself as he did through

Some Christians believe that the God worshiped by the Hebrew people of the pre-Christian era had always revealed himself as he did through  For most Christians, beliefs about God are enshrined in the doctrine of

For most Christians, beliefs about God are enshrined in the doctrine of  In the Incarnation, as traditionally defined, the divine nature of the Son was joined but not mixed with human nature in one divine Person,

In the Incarnation, as traditionally defined, the divine nature of the Son was joined but not mixed with human nature in one divine Person,  In short, this doctrine states that two natures, one human and one divine, are united in the one person of Christ. The Council further taught that each of these natures, the human and the divine, was distinct and complete. This view is sometimes called Dyophysite (meaning two natures) by those who rejected it.

Hypostatic union (from the Greek for substance) is a technical term in Christian theology employed in mainstream Christology to describe the union of two natures, humanity and divinity, in Jesus Christ. A brief definition of the doctrine of two natures can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is identical with the Son, is one person and one hypostasis in two natures: a human and a divine."

The

In short, this doctrine states that two natures, one human and one divine, are united in the one person of Christ. The Council further taught that each of these natures, the human and the divine, was distinct and complete. This view is sometimes called Dyophysite (meaning two natures) by those who rejected it.

Hypostatic union (from the Greek for substance) is a technical term in Christian theology employed in mainstream Christology to describe the union of two natures, humanity and divinity, in Jesus Christ. A brief definition of the doctrine of two natures can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is identical with the Son, is one person and one hypostasis in two natures: a human and a divine."

The  The Gospel according to Matthew and Gospel according to Luke suggest a virgin birth of Jesus Christ. Some now disregard or even argue against this "doctrine" to which most denominations of Christianity ascribe. This section looks at the Christological issues surrounding belief or disbelief in the virgin birth.

A non-virgin birth would seem to require some form of adoptionism. This is because a human conception and birth would seem to yield a fully human Jesus, with some other mechanism required to make Jesus divine as well.

A non-virgin birth would seem to support the full humanity of Jesus. William Barclay: states, "The supreme problem of the virgin birth is that it does quite undeniably differentiate Jesus from all men; it does leave us with an incomplete incarnation."

Barth speaks of the virgin birth as the divine sign "which accompanies and indicates the mystery of the incarnation of the Son."

Donald MacLeod gives several Christological implications of a virgin birth:

* Highlights salvation as a supernatural act of God rather than an act of human initiative.

* Avoids adoptionism (which is virtually required if a normal birth).

* Reinforces the sinlessness of Christ, especially as it relates to Christ being outside the sin of Adam ( original sin).

;Relationship of Persons

The discussion of whether the three distinct persons in the Godhead of the Trinity were of greater, equal, or lesser by comparison was also, like many other areas of early Christology, a subject of debate. In

The Gospel according to Matthew and Gospel according to Luke suggest a virgin birth of Jesus Christ. Some now disregard or even argue against this "doctrine" to which most denominations of Christianity ascribe. This section looks at the Christological issues surrounding belief or disbelief in the virgin birth.

A non-virgin birth would seem to require some form of adoptionism. This is because a human conception and birth would seem to yield a fully human Jesus, with some other mechanism required to make Jesus divine as well.

A non-virgin birth would seem to support the full humanity of Jesus. William Barclay: states, "The supreme problem of the virgin birth is that it does quite undeniably differentiate Jesus from all men; it does leave us with an incomplete incarnation."

Barth speaks of the virgin birth as the divine sign "which accompanies and indicates the mystery of the incarnation of the Son."

Donald MacLeod gives several Christological implications of a virgin birth:

* Highlights salvation as a supernatural act of God rather than an act of human initiative.

* Avoids adoptionism (which is virtually required if a normal birth).

* Reinforces the sinlessness of Christ, especially as it relates to Christ being outside the sin of Adam ( original sin).

;Relationship of Persons

The discussion of whether the three distinct persons in the Godhead of the Trinity were of greater, equal, or lesser by comparison was also, like many other areas of early Christology, a subject of debate. In  The resurrection is perhaps the most controversial aspect of the life of Jesus Christ. Christianity hinges on this point of Christology, both as a response to a particular history and as a confessional response. Some Christians claim that because he was resurrected, the future of the world was forever altered. Most Christians believe that Jesus' resurrection brings reconciliation with God (II Corinthians 5:18), the destruction of death (I Corinthians 15:26), and forgiveness of sins for followers of Jesus Christ.

After Jesus had died, and was buried, the

The resurrection is perhaps the most controversial aspect of the life of Jesus Christ. Christianity hinges on this point of Christology, both as a response to a particular history and as a confessional response. Some Christians claim that because he was resurrected, the future of the world was forever altered. Most Christians believe that Jesus' resurrection brings reconciliation with God (II Corinthians 5:18), the destruction of death (I Corinthians 15:26), and forgiveness of sins for followers of Jesus Christ.

After Jesus had died, and was buried, the  In most of

In most of

Hell in Christian beliefs, is a place or a state in which the

Hell in Christian beliefs, is a place or a state in which the  In

In  The Apostolic Fathers and the Apologists mostly dealt with topics other than original sin. The doctrine of original sin was first developed in 2nd-century Bishop of Lyon Irenaeus's struggle against

The Apostolic Fathers and the Apologists mostly dealt with topics other than original sin. The doctrine of original sin was first developed in 2nd-century Bishop of Lyon Irenaeus's struggle against  The Last Supper appears in all three Synoptic Gospels: Gospel according to Matthew, Matthew, Gospel according to Mark, Mark, and Gospel according to Luke, Luke; and in the First Epistle to the Corinthians, while the last-named of these also indicates something of how early Christians celebrated what Paul the Apostle called the Lord's Supper. As well as the Eucharistic dialogue in Gospel according to John, John chapter 6.

In his First Epistle to the Corinthians (–55), Paul the Apostle gives the earliest recorded description of Jesus' Last Supper: "The Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, 'This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.' In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, 'This cup is the New Covenant, new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me'."