Christ of Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christ of Europe, a messianic

The Relationship of the Reformed Churches of Scotland, England, Western & Eastern Europe from the 1500s to the 1700s

Protestant Reformed Seminary Theological Journal; Volume 36, Number 2, April 2003 The doctrine, based in principles of brotherly esteem and regard for one another, was adopted in messianic terms by Polish Romantics, who referred to their

eSzkola.pl 2004–2009: "Widzenie księdza Piotra." Internet Archive.Sarah Sanderson King, Donald P. Cushman

''Political communication: engineering visions of order in the socialist world''

SUNY Press, 1992. . Page 179, of 212. The concept, which identified Poles collectively with the messianic suffering of the

The concept, which identified Poles collectively with the messianic suffering of the

The Polish self-image as a "Christ among nations" or the martyr of Europe can be traced back to its history of

The Polish self-image as a "Christ among nations" or the martyr of Europe can be traced back to its history of

Google Books

During the periods of foreign occupation, the

Time magazine, Monday, Jan. 04, 1982, p. 5 The invasion by After the failed uprising 10,000 Poles emigrated to France, including many elite. There they came to promote a view of Poland as a heroic victim of Russian tyranny. One of them,

After the failed uprising 10,000 Poles emigrated to France, including many elite. There they came to promote a view of Poland as a heroic victim of Russian tyranny. One of them,

Sabrina P. Ramet, Catholic Historical Review, July 2007. The Catholic Church, in addition to having provided the main support for the

Kumar Krishan, Journal of Political and Military Sociology, Summer 2007 Polish society is currently struggling with the question of how deeply the Catholic Church shall be allowed to remain attached to Polish national identity.

A LOOK AT NAZI ERA IS URGED IN POLAND

New York Times, STEPHEN ENGELBERG, November 7, 1990

The Shadows of Another Time

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christ Of Europe Cultural history of Poland

doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

based in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chris ...

, first became widespread among Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and other various Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an nations through the activities of the Reformed Churches

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

in the 16th to the 18th centuries.Chris ColebornThe Relationship of the Reformed Churches of Scotland, England, Western & Eastern Europe from the 1500s to the 1700s

Protestant Reformed Seminary Theological Journal; Volume 36, Number 2, April 2003 The doctrine, based in principles of brotherly esteem and regard for one another, was adopted in messianic terms by Polish Romantics, who referred to their

homeland

A homeland is a place where a cultural, national, or racial identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth. When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethn ...

as ''the Christ of Europe'' or as ''the Christ of Nations'' crucified in the course of the foreign partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

(1772–1795). Their own unsuccessful struggle for independence from outside powers served as an expression of faith in God's plans for Poland's ultimate ''Rising''. Mesjanizm, historiozofia i symbolika w "Dziadach" cz.IIIeSzkola.pl 2004–2009: "Widzenie księdza Piotra." Internet Archive.Sarah Sanderson King, Donald P. Cushman

''Political communication: engineering visions of order in the socialist world''

SUNY Press, 1992. . Page 179, of 212.

The concept, which identified Poles collectively with the messianic suffering of the

The concept, which identified Poles collectively with the messianic suffering of the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagi ...

, saw Poland as destined – just like Christ – to return to glory. The idea had roots going back to the days of the Ottoman expansion and the wars against the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

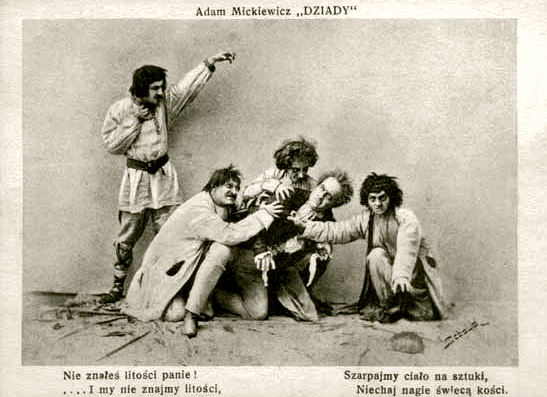

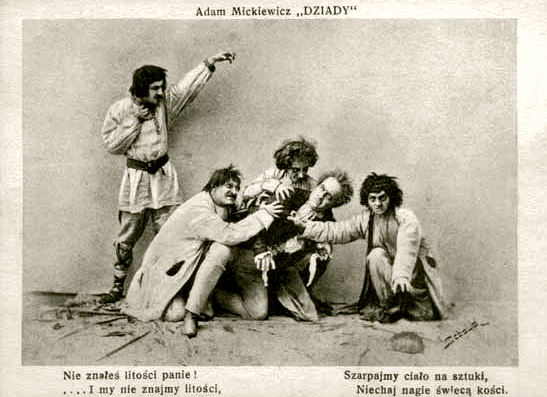

. It was reawakened and promoted during Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

's exile in Paris in the mid-19th century. Mickiewicz (1798-1855) evoked the doctrine of Poland as the "Christ of nations" in his poetic drama

Verse drama is any drama written significantly in verse (that is: with line endings) to be performed by an actor before an audience. Although verse drama does not need to be ''primarily'' in verse to be considered verse drama, significant portion ...

''Dziady

Dziady ( Belarusian: , Russian: , Ukrainian: , pl, Dziady; lit. "grandfathers, eldfathers", sometimes translated as Forefathers' Eve) is a term in Slavic folklore for the spirits of the ancestors and a collection of pre-Christian rites, ritual ...

'' (''Forefathers' Eve''), considered by George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. One of the most popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, bein ...

one of the great works of European Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, through a vision of priest called Piotr (Part III, published in 1832). ''Dziady'' was written in the aftermath of the 1830 uprising against the Russian rule – an event that greatly impacted the author.

Mickiewicz had helped found a student society (the Philomaths

The Philomaths, or Philomath Society ( pl, Filomaci or ''Towarzystwo Filomatów''; from the Greek φιλομαθεῖς "lovers of knowledge"), was a secret student organization that existed from 1817 to 1823 at the Imperial University of Vilni ...

) protesting the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 1 ...

, and was exiled (1824–1829) to central Russia as a result. In the poet's vision, the persecution and suffering of the Poles was to bring salvation to other persecuted nations, just as the death of Christ – crucified by his neighbors – brought redemption to mankind. Thus, the phrase "Poland, the Christ of Nations" ("''Polska Chrystusem narodów''") was born.

Several analysts see the concept as persisting into the modern era.

Historical development

The Polish self-image as a "Christ among nations" or the martyr of Europe can be traced back to its history of

The Polish self-image as a "Christ among nations" or the martyr of Europe can be traced back to its history of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

and suffering under invasions.Daniel Dayan, Elihu Katz, ''Media events: the live broadcasting of history'', (1994) p.163Google Books

During the periods of foreign occupation, the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

served as a bastion of Poland's national identity and language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, and the major promoter of Polish culture

The culture of Poland ( pl, Kultura Polski ) is the product of its geography and distinct historical evolution, which is closely connected to an intricate thousand-year history. Polish culture forms an important part of western civilization and ...

."He Dared to Hope."Time magazine, Monday, Jan. 04, 1982, p. 5 The invasion by

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

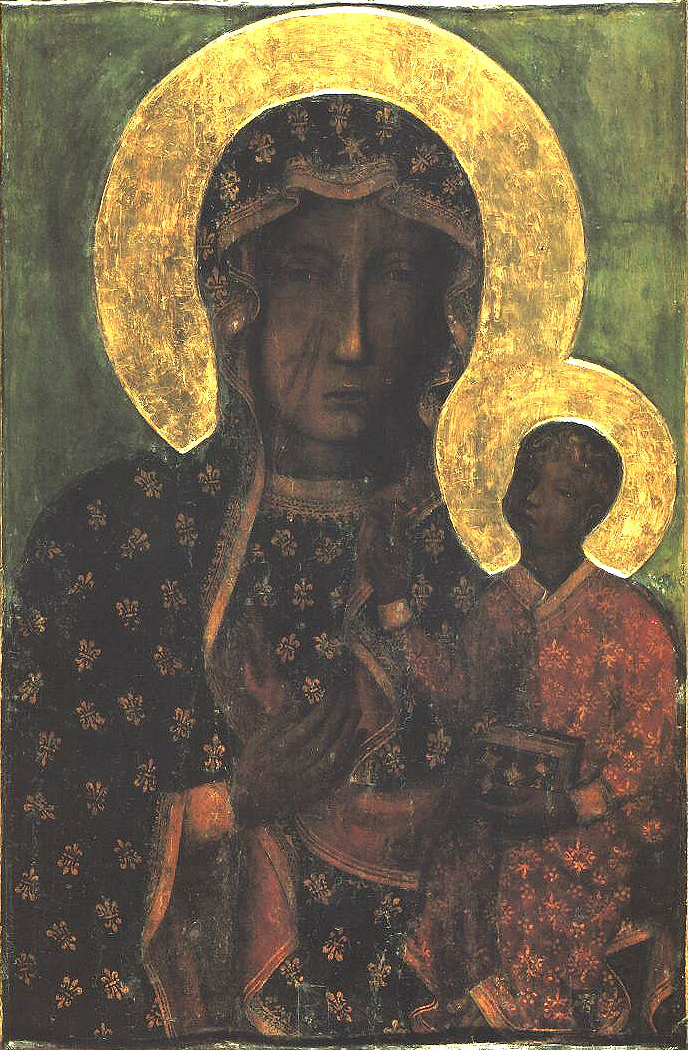

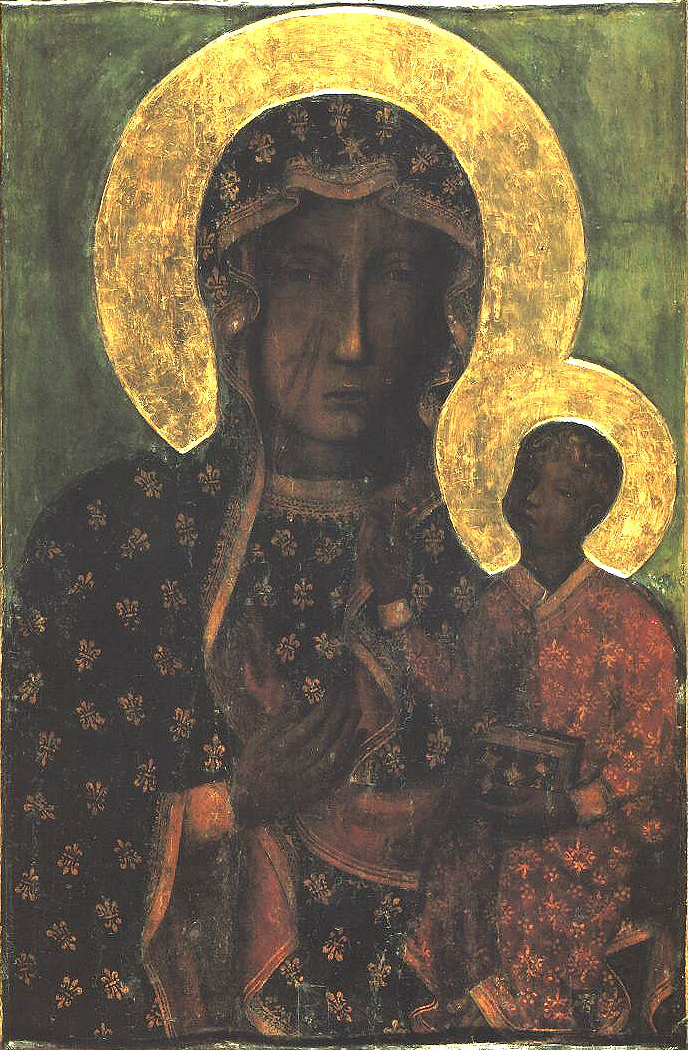

Sweden in 1656 known as the Deluge helped to strengthen the Polish national tie to Catholicism. The Swedes targeted the national identity and religion of the Poles by destroying its religious symbols. The monastery of Jasna Góra Jasna may refer to:

Places

* Jasna, a village in Poland

* Jasná, a village and ski resort in Slovakia

Other uses

* Jasna (given name), a Slavic female given name

* JASNA, the Jane Austen Society of North America

See also

* Yasna

Yasna (;

held out against the Swedes and took on the role of a national sanctuary. According to Anthony Smith, even today the Jasna Góra Madonna is part of a mass religious cult tied to nationalism.Anthony D. Smith "National Identity" (1993), p. 83.

Long before Poland was partitioned the privileged classes (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

) developed a vision of Roman Catholic Poland (Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

at the time) as a nation destined to wage war against Tartars

Tartary ( la, Tartaria, french: Tartarie, german: Tartarei, russian: Тартария, Tartariya) or Tatary (russian: Татария, Tatariya) was a blanket term used in Western European literature and cartography for a vast part of Asia bound ...

, Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

, Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, in the defense of Christian Western civilization ( Antemurale Christianitatis).Ilya Prizel "National identity and foreign

policy: nationalism and leadership in Poland" (1998) p. 41. The Messianic tradition was stoked by the Warsaw Franciscan Wojciech Dębołęcki who in 1633 made a prophecy of the defeat of the Turks and the world supremacy of the Slavs, themselves in turn led by Poland.Roman Jakobson "Selected writings. 6, Early Slavic paths and crossroads. Comparative Slavic Studies: p. 78.

A key element in the Polish view as the guardian of Christianity was the 1683 victory at Vienna against the Turks by John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobi ...

.

Beginning in 1772 Poland suffered a series of partitions by its neighbors Austria, Prussia and Russia, that threatened its national existence. The partitions came to be seen in Poland as a Polish sacrifice for the security of Western civilization.

The failure of the west to support Poland in its 1830 uprising led to the development of a view of Poland as betrayed, suffering, a "Christ of Nations" that was paying for the sins of Europe.

After the failed uprising 10,000 Poles emigrated to France, including many elite. There they came to promote a view of Poland as a heroic victim of Russian tyranny. One of them,

After the failed uprising 10,000 Poles emigrated to France, including many elite. There they came to promote a view of Poland as a heroic victim of Russian tyranny. One of them, Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

, the foremost 19th-century Polish romanticism poet, wrote the patriotic drama ''Dziady'' (directed against the Russians), where he depicts Poland as the Christ of Nations. He also wrote "Verily I say unto you, it is not for you to learn civilization from foreigners, but it is you who are to teach them civilization ... You are among the foreigners like the Apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

among the idolaters".

In "Books of the Polish nation and Polish pilgrimage" Mickiewicz detailed his vision of Poland as a Messias and a Christ of Nations, that would save mankind.Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki "A Concise History of Poland" p.163

::And Poland said, ‘Whosoever will come to me shall be free and equal for I am FREEDOM.’ But the Kings, when they heard it, were frightened in their hearts, and they crucified the Polish nation and laid it in its grave, crying out "We have slain and buried Freedom." But they cried out foolishly ...

::For the Polish Nation did not die. Its body lieth in the grave; but its spirit has descended into the abyss, that is, into the private lives of people who suffer slavery in their own country ... For on the Third Day, the Soul shall return to the Body; and the Nation shall arise and free all the peoples of Europe from Slavery.

The last western failure to adequately support Poland, in Poland labeled Western betrayal

Western betrayal is the view that the United Kingdom, France, and sometimes the United States failed to meet their legal, diplomatic, military, and moral obligations with respect to the Czechoslovak and Polish states during the prelude to and ...

, is perceived to have come in 1945, at the Yalta conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

where the future fate of Europe was being negotiated. The U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Soviet premier Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

that "Poland ... has been a source of trouble for over 500 years". The western powers did not attempt to grant Poland the "victor power" status that France was given, despite the Polish military contribution.Ilya Prizel "National identity and foreign policy: nationalism and leadership in Poland" (1998) p.74

During the communist period going to church was a sign of rebellion against the communist regime. During the time of communist martial law in 1981 it became popular to return to the messianic tradition by for example women wearing the Polish eagle on a black cross, jewelry popular after the failed uprising in 1863.

Partly due to communist influenced education (that used is as a symbol of martyrdom of anti-Nazi and anti-fascist resistance), during the Communist era Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

came to take on different meanings for Jews and Poles, with Poles seeing themselves as the "principal martyrs" of the camp.The Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist PolandSabrina P. Ramet, Catholic Historical Review, July 2007. The Catholic Church, in addition to having provided the main support for the

solidarity movement

Solidarity ( pl, „Solidarność”, ), full name Independent Self-Governing Trade Union "Solidarity" (, abbreviated ''NSZZ „Solidarność”'' ), is a Polish trade union founded in August 1980 at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. Subseq ...

that replaced the communists, also has deep roots of being wedded to the Polish national identity.Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist PolandKumar Krishan, Journal of Political and Military Sociology, Summer 2007 Polish society is currently struggling with the question of how deeply the Catholic Church shall be allowed to remain attached to Polish national identity.

Contemporary status and criticism

Several analysts see the concept as a persistent, unifying force in Poland. A poll taken at the turn of the 20th century indicated that 78% of Poles saw their country as the leading victim of injustice. Its modern applications see Poland as a nation that has "...given the world aPope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and rid the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

."

In 1990 Rev. Stanisław Musiał, deputy editor of a leading Catholic newspaper and with a close relationship to then Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

called for a Polish reappraisal of history that would take these critiques of nationalist ideology seriously. "We have a mythology of ourselves as martyr nation", he wrote. "We are always good. The others are bad. With this national image, it was absolutely impossible that Polish people could do bad things to others."New York Times, STEPHEN ENGELBERG, November 7, 1990

Historical proponents

* Wojciech Dębołęcki *Zygmunt Krasiński

Napoleon Stanisław Adam Feliks Zygmunt Krasiński (; 19 February 1812 – 23 February 1859) was a Polish people, Polish poet traditionally ranked after Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki as one of Poland's Three Bards – the Romantic poets ...

William Safran, ''The Secular and the Sacred'', p. 138.

* Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

* Andrzej Towiański

* Stanisław Wyspiański

Stanisław Mateusz Ignacy Wyspiański (; 15 January 1869 – 28 November 1907) was a Polish playwright, painter and poet, as well as interior and furniture designer. A patriotic writer, he created a series of symbolic, national dramas withi ...

called Poland "the Christ of nations" due to its endurance of suffering

Historical critics

*Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

Stanislaw Gomulka, Antony Polonsky, ''Polish Paradoxes'', (1991) p. 35.

See also

*List of Polish Martyrdom sites

Around six million Polish citizensProject in PosterumRetrieved 20 September 2013.Messianism

Messianism is the belief in the advent of a messiah who acts as the savior of a group of people. Messianism originated as a Zoroastrianism religious belief and followed to Abrahamic religions, but other religions have messianism-related concepts ...

* Messianism in Polish philosophy

Notes

References

External links

The Shadows of Another Time

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christ Of Europe Cultural history of Poland