Chemical Warfare Service on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chemical Corps is the branch of the

JSTOR

, ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 31, No. 2. (Apr.–Jun., 1970), pp. 297–304. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

JSTOR

, ''Military Affairs'', Vol. 20, No. 4. (Winter, 1956), pp. 217–226. Retrieved 14 October 2007. By 1917, the use of chemical weapons by both the Allied and

JSTOR

, ''The Journal of Military History'', Vol. 60, No. 3. (Jul., 1996), pp. 495–511. Retrieved 14 October 2007. In 1917, Secretary of the Interior A center for chemical weapons research was established at American University in

A center for chemical weapons research was established at American University in

Google Books

, PageFree Publishing, Inc., 2004, p. 246, (). A 17 October 1917 memorandum from the

Google Books

, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1921, p. 399. Additional War Department orders established a Chemical Service Section that included 47 commissioned officers and 95 enlisted personnel. Before deploying to France in 1917 many of the soldiers in the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame) spent their time stateside in training that did not emphasize any chemical warfare skills; instead the training focused on drill, marching, guard duty, and inspections.Addison, James Thayer. ''The Story of the First Gas Regiment'',

Internet Archive

, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919, pp. 1–11. Despite the conventional training, the public perceived the 30th as dealing mainly with "poisonous gas and hell fire". By the time those in the 30th Engineers arrived in France most of them knew nothing of chemical warfare and had no specialized equipment. Lengel, Edward G. ''To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918''

Google Books

, Macmillan, 2008, p. 77–78, (). In 1918, the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame) was redesignated the First Gas Regiment and deployed to assist and support Army gas operations, both offensive and defensive.

Google Books

, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 93, (). By 1 November 1918 the CWS included 1,654 commissioned officers and 18,027 enlisted personnel.

Google Books

,

Appendix B: Principal Officials of the War Department and Department of the Army 1900–1963

, ''From Root to McNamara Army Organization and Administration'',

, ''

The Chemical Warfare Service deployed and prepared gas weapons for use throughout the world during

The Chemical Warfare Service deployed and prepared gas weapons for use throughout the world during

Why We Didn't Use Poison Gas in World War II

", '' American Heritage'', August/September 1985, Vol. 36, Issue 5, accessed 16 October 2008. The CWS completed a variety of non-chemical warfare related tasks and missions during the war including producing

Chemical Corps

, ''Globalsecurity.org'', accessed 16 October 2008. During all parts of the war, use of chemical and biological weapons were extremely limited by both sides. Italy used mustard gas and phosgene during the short Second Italo-Abyssinian War, Germany employed chemical agents such as

Torald Sollmann’s Studies of Mustard Gas

,

PDF

, ''Molecular Interventions'', American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Vol. 7, Issue 3 pp.124–28, June 2007, accessed 16 October 2008. In 1943 a U.S. ship carrying a secret Chemical Warfare Service cargo of mustard gas as a precautionary retaliatory measure was sunk in an air raid in Italy, causing 83 deaths and about 600 hospitalized military victims plus a larger number of civilian casualties. In the event, neither chemical nor biological weapons were used on the battlefield by any combatant during World War II. Though the political leadership of the United States remained decidedly against the use of chemical weapons, there were those within the military command structure who advocated the use of such weapons. Following the Battle of Tarawa, during which the U.S. forces suffered more than 3,400 casualties in three days, CWS chief

United States Chemical Policy: Response Considerations

, (

/ref> The Marines felt they were the best weapon they had in the taking of Iwo Jima.

In 1946, the Chemical Warfare Service was re-designated as the "U.S. Army Chemical Corps", a name the branch still uses. With the change came the added mission of defending against

In 1946, the Chemical Warfare Service was re-designated as the "U.S. Army Chemical Corps", a name the branch still uses. With the change came the added mission of defending against

Google Books

, Springer, 2002, pp. 30–31, (), accessed 24 October 2008. During the Korean War (1950–53) chemical soldiers had to again man the 4.2 inch chemical mortar for smoke and high explosive munitions delivery. During the war, the Pine Bluff Arsenal was opened and used for BW production, and research facilities were expanded at Fort Detrick. North Korea, the Soviet Union and China leveled accusations at the United States claiming the U.S. used biological agents during the Korean War; an assertion the U.S. government has denied. From 1952 until 1999 the Chemical Corps School was located at Fort McClellan. After the end of the Korean War, the Army decided to strip the Chemical Corps of the 4.2 inch mortar system and made that an infantry weapon, given its utility against Chinese mortars.

Beginning in 1962 during the Vietnam War, the Chemical Corps operated a program that would become known as Operation Ranch Hand. Ranch Hand was a herbicidal warfare program which used herbicides and defoliants such as Agent Orange.Neilands, J. B. "Vietnam: Progress of the Chemical War,"

Beginning in 1962 during the Vietnam War, the Chemical Corps operated a program that would become known as Operation Ranch Hand. Ranch Hand was a herbicidal warfare program which used herbicides and defoliants such as Agent Orange.Neilands, J. B. "Vietnam: Progress of the Chemical War,"

JSTOR

, ''Asian Survey'', Vol. 10, No. 3. (Mar., 1970), pp. 209–229. Retrieved 14 October 2007. The chemicals were color-coded based on what compound they contained. The U.S. and its allies officially argued that herbicides and defoliants fall outside the definition of "chemical weapons", since these substances were not designed to asphyxiate or poison humans, but to destroy plants which provided cover or concealment to the enemy. The Chemical Corps continued to support the force through the use of incendiary weapons, such as

Chief of Chemical

,

PDF

) ''Army Chemical Review'', July–December 2005, accessed 16 October 2008. In March 1968, the Dugway sheep incident was one of several key events which increased the growing public furor against the corps. An open air spraying of VX (nerve agent), VX was blamed for killing over 4,000 sheep near the US Dugway Proving Ground. The Army eventually settled the case and paid the ranchers. Meanwhile, another incident involving Operation CHASE (Cut Holes and Sink 'Em) was exposed, which sought to dump chemical weapons off of the Florida coast, spurring concerns over the damage to the ocean environment and risk of chemical munitions washing up on shore. The criticism of the Army culminated with the near-disbanding of the Chemical Corps in the aftermath of the War.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the chemical warfare capabilities of the United States began to decline due to, in part, a decline in public opinion concerning the corps. The corps continued to be plagued with bad press and mishaps. A Operation Red Hat, 1969 incident, in which 23 soldiers and one Japanese civilian were exposed to sarin on the island of Okinawa while cleaning sarin-filled bombs, created international concern while revealing the presence of chemical munitions in Southeast Asia.Tom Bowman (journalist), Bowman, Tom.

In March 1968, the Dugway sheep incident was one of several key events which increased the growing public furor against the corps. An open air spraying of VX (nerve agent), VX was blamed for killing over 4,000 sheep near the US Dugway Proving Ground. The Army eventually settled the case and paid the ranchers. Meanwhile, another incident involving Operation CHASE (Cut Holes and Sink 'Em) was exposed, which sought to dump chemical weapons off of the Florida coast, spurring concerns over the damage to the ocean environment and risk of chemical munitions washing up on shore. The criticism of the Army culminated with the near-disbanding of the Chemical Corps in the aftermath of the War.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the chemical warfare capabilities of the United States began to decline due to, in part, a decline in public opinion concerning the corps. The corps continued to be plagued with bad press and mishaps. A Operation Red Hat, 1969 incident, in which 23 soldiers and one Japanese civilian were exposed to sarin on the island of Okinawa while cleaning sarin-filled bombs, created international concern while revealing the presence of chemical munitions in Southeast Asia.Tom Bowman (journalist), Bowman, Tom.

Fort Detrick: From Biowarfare To Biodefense

, NPR, 1 August 2008, accessed 10 October 2008. The same year as this sarin mishap, President Richard Nixon reaffirmed a no first-use policy on chemical weapons as well as renouncing the use of biological agents. When the U.S. BW program ended in 1969, it had developed seven standardized biological weapons in the form of agents that cause anthrax, tularemia, brucellosis, Q-fever, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, VEE, and botulism. In addition, Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B was produced as an incapacitating agent. During summer 1972, Nixon nominated General Creighton Abrams for the post of Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Army Chief of Staff and upon assuming the post the general and others began to address the reformation of the Army in the wake of Vietnam. As soon as Abrams was sworn in he began to investigate the possibility of merging Chemical Corps into other Army branches. An ad hoc committee, designed to study possibilities, recommended that the Chemical Corps' smoke and flame mission be integrated into the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Corps and the chemical operations be integrated into the United States Army Ordnance Corps, Ordnance Corps. The groups recommendations were accepted in December 1972 and the United States Army Chemical Corps was officially disbanded, but not formally disestablished, by the Army on 11 January 1973.Mauroni, Al.

The US Army Chemical Corps: Past, Present, and Future

", ''Army Historical Foundation''. Retrieved 26 November 2007. To formally disestablish the corps, the U.S. Congress had to approve the move, because it had officially established the Chemical Corps in 1946. Congress chose to table action on the fate of the Chemical Corps, leaving it in limbo for several years. Recruitment and career advancement was halted and the Chemical School at Fort McClellan was shut down and moved to Aberdeen Proving Grounds.*Mauroni, Albert J. ''Chemical-Biological Defense: U.S. Military Policies and Decisions in the Gulf War'',

Google Books

, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut: 1998, pages 2–3, (). In 1974 Abrams died in office after the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and a coalition of Arab states. The results of the war demonstrated the desire of the Soviet Union to continue its pursuit of offensive chemical and biological capabilities.

JSTOR

, ''International Security'', Volume 3, Number 1. (Summer, 1978), pages 55–82. Retrieved 14 October 2007. Secretary of the Army Martin R. Hoffmann rescinded the 1972 recommendations, and in 1976 Army Chief of Staff General Bernard W. Rogers ordered the resumption of Chemical Corps officer commissioning. However, the U.S. Army Chemical School at Fort McClellan, Anniston, Alabama did not reopen until 1980.

Are Our Troops Ready for Biological and Chemical Attacks?

, ''Policy Analysis'', CATO Institute, 5 February 2003, accessed 12 October 2008. The possibility of CB attack forced the army to respond with NBC defense crash courses in theater. Troops deployed to the Gulf with protective masks at the ready, protective clothing was made available to those troops whose vicinity to the enemy or mission required it. Large scale drills were conducted in the desert to better acclimatize troops to wearing the bulky protective clothing (called MOPP (protective gear), MOPP gear) in hot weather conditions.Hammond, James W. ''Poison Gas: The Myth Versus Reality'',

Google Books

, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, (), page 91. Though Saddam Hussein had renounced the use of chemical weapons in 1989, many did not believe he would really honor that during a conflict with the United States and the broader coalition forces. As American troops headed to the desert, analysts speculated about their vulnerability to CB attack. Although the location of Hussein's chemical munitions was unknown, their existence was never doubted. Gulf War I was fought without the Iraqi Army unleashing chemical or biological munitions; Eric R. Taylor, of the CATO Institute, maintained that the effective, U.S. threat of nuclear retaliation halted Hussein from employing his chemical weapons. The locations of many of Iraq's chemical stockpiles were never uncovered and there is widespread speculation that U.S. troops were exposed to chemical munitions while destroying weapons caches, particularly near the Khamisiyah storage site.Director of Central Intelligence, DCI Persian Gulf War Illnesses Task Force.

Khamisiyah: A Historical Perspective on Related Intelligence

, 9 April 1997, accessed 12 October 2008. After the war, analysis suggested the chemical defense capabilities of U.S. forces were woefully inadequate during and after the conflict. In addition, some experts, such as Jonathan B. Tucker, suggest that the Iraqis did indeed employ chemical weapons during the war.Jonathan B. Tucker, Tucker, Jonathan B.

Evidence Iraq Used Chemical Weapons During the 1991 Persian Gulf War

, ''The Nonproliferation Review'', Spring/Summer 1997, accessed 12 October 2008.

, United States General Accounting Office, via Federation of American Scientists, 12 March 1996, accessed 12 October 2008.

The Chemical Corps, like all branches of the U.S. Army, uses specific insignia to indicate a soldier's affiliation with the corps. The Chemical Corps branch insignia consists of a cobalt blue, Vitreous enamel, enamel benzene ring superimposed over two crossed gold retorts. The branch insignia, which was adopted in 1918 by the fledgling Chemical Service, measures .5 inches in height by 1.81 inches in width. Crossed shells with a dragon head was also commonly used in France for the Chemical service. The Chemical Warfare Service approved the insignia in 1921 and in 1924 the ring adopted the cobalt blue enamel. When the Chemical Warfare Service changed designations to the Chemical Corps in 1946 the symbol was retained.Chemical Corps

The Chemical Corps, like all branches of the U.S. Army, uses specific insignia to indicate a soldier's affiliation with the corps. The Chemical Corps branch insignia consists of a cobalt blue, Vitreous enamel, enamel benzene ring superimposed over two crossed gold retorts. The branch insignia, which was adopted in 1918 by the fledgling Chemical Service, measures .5 inches in height by 1.81 inches in width. Crossed shells with a dragon head was also commonly used in France for the Chemical service. The Chemical Warfare Service approved the insignia in 1921 and in 1924 the ring adopted the cobalt blue enamel. When the Chemical Warfare Service changed designations to the Chemical Corps in 1946 the symbol was retained.Chemical Corps

," ''Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army'', The Institute of Heraldry. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

The regimental motto, ''Elementis Regamus Proelium'' translates to: "We rule the battle by means of the elements." The Chemical Corps regimental insignia was approved on 2 May 1986. The insignia consists of a 1.2 inch shield of gold and blue emblazoned with a dragon and a tree. The shield is enclosed on three sides by a blue ribbon with ''Elementis regamus proelium'' written around it in gold lettering. The phrase translates to: "We rule the battle through the elements.". The regimental insignia incorporates specific symbolism in its design. The colors, gold and blue, are the colors of the Chemical Corps, while the tree's trunk is battle scarred, a reference to the historical beginnings of U.S. chemical warfare, battered tree trunks were often the only reference points that chemical mortar teams had across no man's land during World War I.Regimental Crest

The regimental motto, ''Elementis Regamus Proelium'' translates to: "We rule the battle by means of the elements." The Chemical Corps regimental insignia was approved on 2 May 1986. The insignia consists of a 1.2 inch shield of gold and blue emblazoned with a dragon and a tree. The shield is enclosed on three sides by a blue ribbon with ''Elementis regamus proelium'' written around it in gold lettering. The phrase translates to: "We rule the battle through the elements.". The regimental insignia incorporates specific symbolism in its design. The colors, gold and blue, are the colors of the Chemical Corps, while the tree's trunk is battle scarred, a reference to the historical beginnings of U.S. chemical warfare, battered tree trunks were often the only reference points that chemical mortar teams had across no man's land during World War I.Regimental Crest

," ''U.S. Army Chemical School'', United States Army — Fort Leonard Wood. Retrieved 14 October 2007. The tree design was taken from the coat of arms of the First Gas Regiment. The mythical chlorine breathing green dragon symbolizes the first use of chemical weapons in warfare (chlorine). Individual Chemical Corps soldiers are often referred to as "Dragon Soldiers."Mauroni, Albert J. ''Where are the WMDs?''

Google Books

, Naval Institute Press, 2006, (), p. 4.

," ''Chemical Corps Regimental Association'', official site. Retrieved 27 November 2007. The organization conducts annual inductions, and the honor is considered the highest offered by the corps.Whitacre, Kimberly S. and Jones, Ricardo.

2006 U.S. Army Chemical Corps Hall of Fame Inductees

", ''Army Chemical Review'', July—December 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

online

, about the Chemical Corps Museum at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri *Mims, Samuel E. "Survey: Perceptions About the Army Chemical Corps"

AbstractPDF

, April 1992, ''United States Army War College, Army War College'': Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, accessed 12 October 2008.

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

tasked with defending against chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., w ...

, biological, radiological

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visib ...

, and nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

(CBRN

Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence (CBRN defence) are protective measures taken in situations in which chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear warfare (including terrorism) hazards may be present. CBRN defence consi ...

) weapons

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

. The Chemical Warfare Service was established on 28 June 1918, combining activities that until then had been dispersed among five separate agencies of the United States federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fe ...

. It was made a permanent branch of the Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

by the National Defense Act of 1920

The National Defense Act of 1920 (or Kahn Act) was sponsored by United States Representative Julius Kahn, Republican of California. This legislation updated the National Defense Act of 1916 to reorganize the United States Army and decentralize ...

. In 1945, it was redesignated the Chemical Corps.

History

Origins

Discussion of the topic dates back to theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. A letter to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

dated 5 April 1862 from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

resident John Doughty proposed the use of chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

shells to drive the Confederate Army from its positions. Doughty included a detailed drawing of the shell with his letter. It is unknown how the military reacted to Doughty's proposal but the letter was unnoticed in a pile of old official documents until modern times. Another American, Forrest Shepherd, also proposed a chemical weapon attack against the Confederates. Shepherd's proposal involved hydrogen chloride

The compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colourless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hydrogen chloride ga ...

, an attack that would have likely been non-lethal

Non-lethal weapons, also called nonlethal weapons, less-lethal weapons, less-than-lethal weapons, non-deadly weapons, compliance weapons, or pain-inducing weapons are weapons intended to be less likely to kill a living target than conventional ...

but may have succeeded in driving enemy soldiers from their positions. Shepherd was a well-known geologist at the time and his proposal was in the form of a letter directly to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

.Miles, Wyndham. "The Idea of Chemical Warfare in Modern Times,"JSTOR

, ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 31, No. 2. (Apr.–Jun., 1970), pp. 297–304. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

World War I

The earliest predecessors to the United States Army Chemical Corps owe their existence to changes of military technology early in World War I. By 1915, the combatants were using poison gases and chemical irritants on the battlefield. In that year, the United States War Department first became interested in providing individual soldiers with personal protection against chemical warfare and they tasked the Medical Department with developing the technology. Nevertheless, troops were neither supplied withmasks

A mask is an object normally worn on the face, typically for protection, disguise, performance, or entertainment and often they have been employed for rituals and rights. Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practi ...

nor trained for offensive gas warfare until the U.S. became involved in World War I in 1917.Brophy, Leo P. "Origins of the Chemical Corp,"JSTOR

, ''Military Affairs'', Vol. 20, No. 4. (Winter, 1956), pp. 217–226. Retrieved 14 October 2007. By 1917, the use of chemical weapons by both the Allied and

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

had become commonplace along the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

, Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Italian Fronts, occurring daily in some regions.van Courtland Moon, John Ellis. "United States Chemical Warfare Policy in World War II: A Captive of Coalition Policy?"JSTOR

, ''The Journal of Military History'', Vol. 60, No. 3. (Jul., 1996), pp. 495–511. Retrieved 14 October 2007. In 1917, Secretary of the Interior

Franklin K. Lane

Franklin Knight Lane (July 15, 1864 – May 18, 1921) was an American progressive politician from California. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as United States Secretary of the Interior from 1913 ...

, directed the Bureau of Mines to assist the Army and Navy in creating a gas war program. Researchers at the Bureau of Mines had experience in developing gas masks for miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face; cutting, blasting, ...

, drawing poisonous air through an activated carbon filter. After the Director of the Bureau of Mines, Van H. Manning, formally offered the bureau's service to the Military Committee of the National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

, the council appointed a Subcommittee on Noxious Gases. Manning recruited chemists from industry, universities, and government to help study mustard-gas poisoning, investigate and mass-produce new toxic chemicals, and develop gas-masks and other treatments.

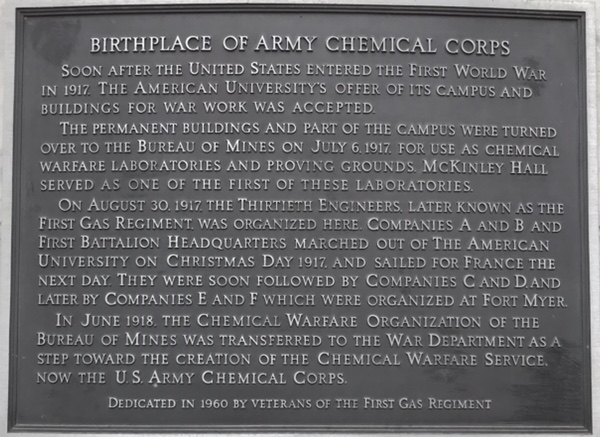

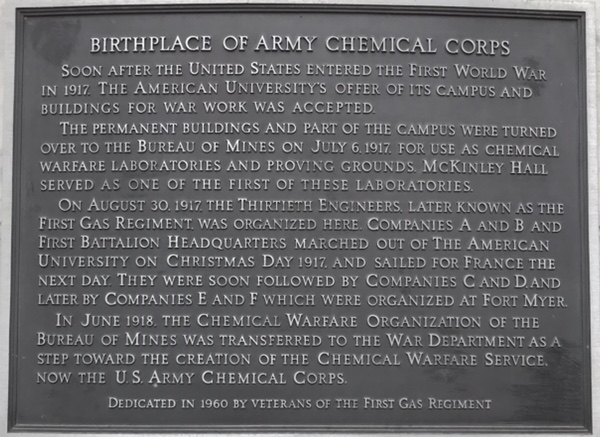

A center for chemical weapons research was established at American University in

A center for chemical weapons research was established at American University in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

to house researchers. The U.S. military paid to convert classrooms into laboratories. Within a year of setting up the center, the number of scientists and technicians employed there would increase from 272 to over 1,000. Industrial plants were established in nearby cities to synthesize toxic chemicals for use in research and armaments. Shells were filled with toxic gas in Edgewood, Maryland

Edgewood is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Harford County, Maryland, United States. The population was 25,562 at the 2010 census, up from 23,378 in 2000.

Geography

Edgewood is located in southwestern Harford Coun ...

. Women were employed to produce gas masks in Long Island City.

On 5 July 1917 General John J. Pershing oversaw the creation of a new military unit dealing with gas, the Gas Service Section. The government recruited soldiers for it to be based at Camp American University, Washington, D.C. The predecessor to the 1st Gas Regiment

The 2nd Chemical Battalion is a United States Army chemical unit stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, United States, and is part of the 48th Chemical Brigade. The battalion can trace its lineage from the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame) and has s ...

was the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame). The 30th was activated on 15 August 1917 at Camp American UniversityEldredge, Walter J. ''Finding My Father's War: A Baby Boomer and the 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion in World War II'',Google Books

, PageFree Publishing, Inc., 2004, p. 246, (). A 17 October 1917 memorandum from the

Adjutant General

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

to the Chief of Engineers

The Chief of Engineers is a principal United States Army staff officer at The Pentagon. The Chief advises the Army on engineering matters, and serves as the Army's topographer and proponent for real estate and other related engineering programs. ...

directed that the Gas Service Section consist of four majors, six captains, 10 first lieutenants and 15 second lieutenants.United States Army: Office of the Judge Advocate General. ''Military Laws of the United States (Army)'',Google Books

, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1921, p. 399. Additional War Department orders established a Chemical Service Section that included 47 commissioned officers and 95 enlisted personnel. Before deploying to France in 1917 many of the soldiers in the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame) spent their time stateside in training that did not emphasize any chemical warfare skills; instead the training focused on drill, marching, guard duty, and inspections.Addison, James Thayer. ''The Story of the First Gas Regiment'',

Internet Archive

, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919, pp. 1–11. Despite the conventional training, the public perceived the 30th as dealing mainly with "poisonous gas and hell fire". By the time those in the 30th Engineers arrived in France most of them knew nothing of chemical warfare and had no specialized equipment. Lengel, Edward G. ''To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918''

Google Books

, Macmillan, 2008, p. 77–78, (). In 1918, the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame) was redesignated the First Gas Regiment and deployed to assist and support Army gas operations, both offensive and defensive.

Formation

On 28 June 1918, the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) was officially formed and encompassed the "Gas Service" and "Chemical Service" Sections.Brown, Jerold E. ''Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army'',Google Books

, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 93, (). By 1 November 1918 the CWS included 1,654 commissioned officers and 18,027 enlisted personnel.

United States War Department

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, a ...

. ''Annual Report of the Secretary of War'',Google Books

,

U.S. Government Printing Office

The United States Government Publishing Office (USGPO or GPO; formerly the United States Government Printing Office) is an agency of the legislative branch of the United States Federal government. The office produces and distributes information ...

, 1918, p. 60. Major General William L. Sibert served as the first director of the CWS on the day it was created,Hewes, James E., Jr.Appendix B: Principal Officials of the War Department and Department of the Army 1900–1963

, ''From Root to McNamara Army Organization and Administration'',

Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

, United States Army, Washington D.C.: 1975. and he resigned in April 1920.General Sibert Resigns: Head of Army's Chemical Warfare Service Resented Transfer, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', 7 April 1920, accessed 16 October 2008.

In the interwar period, the Chemical Warfare Service maintained its arsenal despite public pressure and presidential wishes in favor of disarmament. Major General Amos Fries

Amos Alfred Fries (1873–1963) was a general in the United States Army and 1898 graduate of the United States Military Academy. Fries was the second chief of the army's Chemical Warfare Service, established during World War I. Fries served ...

, the CWS chief from 1920–29, viewed chemical disarmament as a Communist plot. Through his instigation and lobbying, the CWS and its various Congressional, chemist, and chemical company allies were able to halt the U.S. Senate's ratification of the 1925 Geneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

which forbade "first use" of chemical weapons. Even countries who had signed the Geneva Protocol still produced and stockpiled chemical weapons, since the Protocol did not prohibit retaliation in kind.

Roosevelt on renaming Service to Corps, 1937

In 1937, PresidentRoosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

opposed changing the name of the Service to Corps, stating:

It is my thought that the major functions of the Chemical Warfare Service are those of a "Service" rather than a "Corps." It is desirable to designate as a Corps only those supply branches of the Army which are included in the line of the Army. To have changed the name to the "Chemical Service" would have been more in keeping with its functions than to designate it as the "Chemical Corps."

I have a far more important objection to this change of name. It has been and is the policy of this Government to do everything in its power to outlaw the use of chemicals in warfare. Such use is inhuman and contrary to what modern civilization should stand for.

I am doing everything in my power to discourage the use of gases and other chemicals in any war between nations. While, unfortunately, the defensive necessities of the United States call for study of the use of chemicals in warfare, I do not want the Government of the United States to do anything to aggrandize or make permanent any special bureau of the Army or the Navy engaged in these studies. I hope the time will come when the Chemical Warfare Service can be entirely abolished.

To dignify this Service by calling it the "Chemical Corps" is, in my judgment, contrary to a sound public policy.

World War II

The Chemical Warfare Service deployed and prepared gas weapons for use throughout the world during

The Chemical Warfare Service deployed and prepared gas weapons for use throughout the world during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. However, these weapons were never used in combat. Despite the lack of chemical warfare during the conflict, the CWS saw its funding and personnel increase substantially due to concerns that the Germans and Japanese had a formidable chemical weapons capability. By 1942 the CWS employed 60,000 soldiers and civilians and was appropriated $1 billion.Bernstein, Barton J.Why We Didn't Use Poison Gas in World War II

", '' American Heritage'', August/September 1985, Vol. 36, Issue 5, accessed 16 October 2008. The CWS completed a variety of non-chemical warfare related tasks and missions during the war including producing

incendiaries

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, th ...

for flame throwers, flame tank

A flame tank is a type of tank equipped with a flamethrower, most commonly used to supplement combined arms attacks against fortifications, confined spaces, or other obstacles. The type only reached significant use in the Second World War, dur ...

s and other weapons. Chemical soldiers were also involved in smoke generation missions. Chemical mortar battalion The United States chemical mortar battalions were army units attached to U.S. infantry divisions during World War II. They were armed with 4.2-inch (107 mm) chemical mortars. For this reason they were also called the "Four-deucers".

Chemical morta ...

s used the 4.2-inch chemical mortar to support armor and infantry units.Pike, John.Chemical Corps

, ''Globalsecurity.org'', accessed 16 October 2008. During all parts of the war, use of chemical and biological weapons were extremely limited by both sides. Italy used mustard gas and phosgene during the short Second Italo-Abyssinian War, Germany employed chemical agents such as

Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

against Jews, political prisoners and other victims in extermination camps during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, and Japan employed chemical and biological weapons in China.Cox, Brian M.Torald Sollmann’s Studies of Mustard Gas

,

, ''Molecular Interventions'', American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Vol. 7, Issue 3 pp.124–28, June 2007, accessed 16 October 2008. In 1943 a U.S. ship carrying a secret Chemical Warfare Service cargo of mustard gas as a precautionary retaliatory measure was sunk in an air raid in Italy, causing 83 deaths and about 600 hospitalized military victims plus a larger number of civilian casualties. In the event, neither chemical nor biological weapons were used on the battlefield by any combatant during World War II. Though the political leadership of the United States remained decidedly against the use of chemical weapons, there were those within the military command structure who advocated the use of such weapons. Following the Battle of Tarawa, during which the U.S. forces suffered more than 3,400 casualties in three days, CWS chief

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

William N. Porter pushed superiors to approve the use of poison gas against Japan. "We have an overwhelming advantage in the use of gas. Properly used gas could shorten the war in the Pacific and prevent loss of many American lives," Porter said.

Popular support was not completely lacking. Some newspaper editorials supported the use of chemical weapons in the Pacific theater. The '' New York Daily News'' proclaimed in 1943, "We Should Gas Japan", and the ''Washington Times Herald

The ''Washington Times-Herald'' (1939–1954) was an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It was created by Eleanor "Cissy" Patterson of the Medill–McCormick–Patterson family (long-time owners of the ''Chicago Tribune'' ...

'' wrote in 1944, "We Should Have Used Gas at Tarawa because "You Can Cook 'Em Better with Gas". Despite rising between 1944 and 1945, popular public opinion never rose above 40 percent in favor of the use of gas weapons.Vandyke, Lewis L.United States Chemical Policy: Response Considerations

, (

Master's thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

), 7 June 1991, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

, Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Kansas, accessed 16 October 2008.

Where there was support for Chemical Warfare was in V Amphibious Corps

The V Amphibious Corps (VAC) was a formation of the United States Marine Corps which was composed of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Marine Divisions in World War II. The three divisions were the amphibious landing force for the United States Fifth Fleet ...

and X U.S. Army. Colonel George F. Unmacht (US Army) became commander of the Army's Chemical Warfare Service, Pacific Ocean Area in 1943. Along with that he was the Hawaii Territorial Coordinator for Civilian Gas Defense and Joint service Pacific theater chief chemical warfare officer under Adm. Nimitz. Under his leadership the research, development, and production of flamethrowing tanks and napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated alu ...

took place at Schofield Barracks

Schofield Barracks is a United States Army installation and census-designated place (CDP) located in the City and County of Honolulu and in the Wahiawa District of the Hawaiian island of Oahu, Hawaii. Schofield Barracks lies adjacent to the t ...

. His crews of Seabee

, colors =

, mascot = Bumblebee

, battles = Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Cape Gloucester, Los Negros, Guam, Peleliu, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, Tinian, Iwo Jima, Philippin ...

s produced more flamethrowing tanks than commercial production in the States. The Army and Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

felt the tanks saved many American troops on Iwo Jima and Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

.CHAPTER XV, The Flame Thrower in the Pacific: Marianas to Okinawa, WWII Chemical in Combat, Dec 2001, p. 55/ref> The Marines felt they were the best weapon they had in the taking of Iwo Jima.

Post World War II and Korean War, 1945–53

In 1946, the Chemical Warfare Service was re-designated as the "U.S. Army Chemical Corps", a name the branch still uses. With the change came the added mission of defending against

In 1946, the Chemical Warfare Service was re-designated as the "U.S. Army Chemical Corps", a name the branch still uses. With the change came the added mission of defending against nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear ...

, in addition, the corps continued to refine its offensive and defensive chemical capabilities. Immediately following World War II, production of U.S. biological warfare (BW) agents went from "factory-level to laboratory-level". Meanwhile, work on BW delivery systems increased. Live testing in Panama was carried out during the San Jose Project.

From the end of World War II through the Korean War, the U.S. Army, the Chemical Corps and the U.S. Air Force made great strides in their biological warfare programs, especially concerning delivery systems.Croddy, Eric C. and Hart, C. Perez-Armendariz J., ''Chemical and Biological Warfare'',Google Books

, Springer, 2002, pp. 30–31, (), accessed 24 October 2008. During the Korean War (1950–53) chemical soldiers had to again man the 4.2 inch chemical mortar for smoke and high explosive munitions delivery. During the war, the Pine Bluff Arsenal was opened and used for BW production, and research facilities were expanded at Fort Detrick. North Korea, the Soviet Union and China leveled accusations at the United States claiming the U.S. used biological agents during the Korean War; an assertion the U.S. government has denied. From 1952 until 1999 the Chemical Corps School was located at Fort McClellan. After the end of the Korean War, the Army decided to strip the Chemical Corps of the 4.2 inch mortar system and made that an infantry weapon, given its utility against Chinese mortars.

Chemical Corps Intelligence Agency

The Chemical Corps Intelligence Agency (CCIA) was founded in 1955 within a facility at Arlington Hall Station, Virginia. which also housed the United States Army Security Agency, Army Security Agency, the National Security Agency (NSA) and the Defense Intelligence Agency's National Intelligence University. The CCIA accomplished the intelligence function of the U.S. Army Chemical Corps. Its mission was to support the national intelligence effort with particular emphasis on the military aspects of Chemical, Biological and Radiological (CBR) intelligence information. U.S. Army Chemical Corps Information and Liaison Office, Europe (CCILO–E) was established and located in Frankfurt, Germany. During November and December 1961 two CCIA officers visited the Far East on an intelligence collection trip. This visit led to a recommendation by CCIA to establish an information and liaison office in Tokyo patterned on the Frankfurt agency. The Chief Chemical Officer and Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence (ACS/I) approved the recommendation and foresaw an activation date in financial year 1964. Two CCIA staff members again toured selected U.S. intelligence agencies in Japan, Republic of Korea, Korea, Okinawa, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Hong Kong in the third quarter of financial year 1962. The purposes were to establish liaison with the Chemical Corps personnel, to reemphasize the importance of CBR intelligence, and to provide on the spot guidance and discuss the establishment of a U.S. Army Chemical Corps Information and Liaison Office in Tokyo.Vietnam

Beginning in 1962 during the Vietnam War, the Chemical Corps operated a program that would become known as Operation Ranch Hand. Ranch Hand was a herbicidal warfare program which used herbicides and defoliants such as Agent Orange.Neilands, J. B. "Vietnam: Progress of the Chemical War,"

Beginning in 1962 during the Vietnam War, the Chemical Corps operated a program that would become known as Operation Ranch Hand. Ranch Hand was a herbicidal warfare program which used herbicides and defoliants such as Agent Orange.Neilands, J. B. "Vietnam: Progress of the Chemical War,"JSTOR

, ''Asian Survey'', Vol. 10, No. 3. (Mar., 1970), pp. 209–229. Retrieved 14 October 2007. The chemicals were color-coded based on what compound they contained. The U.S. and its allies officially argued that herbicides and defoliants fall outside the definition of "chemical weapons", since these substances were not designed to asphyxiate or poison humans, but to destroy plants which provided cover or concealment to the enemy. The Chemical Corps continued to support the force through the use of incendiary weapons, such as

napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated alu ...

, and riot control measures, among other missions. As the war progressed into the late 1960s, public sentiment against the Chemical Corps increased because of the Army's continued use of herbicides, criticized in the press as being against the Geneva Protocol, napalm, and riot control agents.

Besides supplying flame weapons, and preparing for any eventuality of weapons of mass destruction, the Vietnam era Chemical Corps also developed "people sniffers", a type of personnel detector. Major Herb Thornton led chemical soldiers, who became known as Tunnel rat (military), tunnel rats and developed techniques for clearing Củ Chi tunnels, enemy tunnels in Vietnam.Lillie, Stanley H.Chief of Chemical

,

) ''Army Chemical Review'', July–December 2005, accessed 16 October 2008.

In March 1968, the Dugway sheep incident was one of several key events which increased the growing public furor against the corps. An open air spraying of VX (nerve agent), VX was blamed for killing over 4,000 sheep near the US Dugway Proving Ground. The Army eventually settled the case and paid the ranchers. Meanwhile, another incident involving Operation CHASE (Cut Holes and Sink 'Em) was exposed, which sought to dump chemical weapons off of the Florida coast, spurring concerns over the damage to the ocean environment and risk of chemical munitions washing up on shore. The criticism of the Army culminated with the near-disbanding of the Chemical Corps in the aftermath of the War.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the chemical warfare capabilities of the United States began to decline due to, in part, a decline in public opinion concerning the corps. The corps continued to be plagued with bad press and mishaps. A Operation Red Hat, 1969 incident, in which 23 soldiers and one Japanese civilian were exposed to sarin on the island of Okinawa while cleaning sarin-filled bombs, created international concern while revealing the presence of chemical munitions in Southeast Asia.Tom Bowman (journalist), Bowman, Tom.

In March 1968, the Dugway sheep incident was one of several key events which increased the growing public furor against the corps. An open air spraying of VX (nerve agent), VX was blamed for killing over 4,000 sheep near the US Dugway Proving Ground. The Army eventually settled the case and paid the ranchers. Meanwhile, another incident involving Operation CHASE (Cut Holes and Sink 'Em) was exposed, which sought to dump chemical weapons off of the Florida coast, spurring concerns over the damage to the ocean environment and risk of chemical munitions washing up on shore. The criticism of the Army culminated with the near-disbanding of the Chemical Corps in the aftermath of the War.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the chemical warfare capabilities of the United States began to decline due to, in part, a decline in public opinion concerning the corps. The corps continued to be plagued with bad press and mishaps. A Operation Red Hat, 1969 incident, in which 23 soldiers and one Japanese civilian were exposed to sarin on the island of Okinawa while cleaning sarin-filled bombs, created international concern while revealing the presence of chemical munitions in Southeast Asia.Tom Bowman (journalist), Bowman, Tom.Fort Detrick: From Biowarfare To Biodefense

, NPR, 1 August 2008, accessed 10 October 2008. The same year as this sarin mishap, President Richard Nixon reaffirmed a no first-use policy on chemical weapons as well as renouncing the use of biological agents. When the U.S. BW program ended in 1969, it had developed seven standardized biological weapons in the form of agents that cause anthrax, tularemia, brucellosis, Q-fever, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, VEE, and botulism. In addition, Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B was produced as an incapacitating agent. During summer 1972, Nixon nominated General Creighton Abrams for the post of Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Army Chief of Staff and upon assuming the post the general and others began to address the reformation of the Army in the wake of Vietnam. As soon as Abrams was sworn in he began to investigate the possibility of merging Chemical Corps into other Army branches. An ad hoc committee, designed to study possibilities, recommended that the Chemical Corps' smoke and flame mission be integrated into the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Corps and the chemical operations be integrated into the United States Army Ordnance Corps, Ordnance Corps. The groups recommendations were accepted in December 1972 and the United States Army Chemical Corps was officially disbanded, but not formally disestablished, by the Army on 11 January 1973.Mauroni, Al.

The US Army Chemical Corps: Past, Present, and Future

", ''Army Historical Foundation''. Retrieved 26 November 2007. To formally disestablish the corps, the U.S. Congress had to approve the move, because it had officially established the Chemical Corps in 1946. Congress chose to table action on the fate of the Chemical Corps, leaving it in limbo for several years. Recruitment and career advancement was halted and the Chemical School at Fort McClellan was shut down and moved to Aberdeen Proving Grounds.*Mauroni, Albert J. ''Chemical-Biological Defense: U.S. Military Policies and Decisions in the Gulf War'',

Google Books

, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut: 1998, pages 2–3, (). In 1974 Abrams died in office after the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and a coalition of Arab states. The results of the war demonstrated the desire of the Soviet Union to continue its pursuit of offensive chemical and biological capabilities.

Post Vietnam, 1975–80

By the mid–1970s the chemical warfare and defense capability of the United States had degraded and by 1978 the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff characterized U.S. ability to conduct operations in a chemical environment as "not prepared."Hoeber, Amoretta M. and Douglass, Jr. Joseph D. "The Neglected Threat of Chemical Warfare",JSTOR

, ''International Security'', Volume 3, Number 1. (Summer, 1978), pages 55–82. Retrieved 14 October 2007. Secretary of the Army Martin R. Hoffmann rescinded the 1972 recommendations, and in 1976 Army Chief of Staff General Bernard W. Rogers ordered the resumption of Chemical Corps officer commissioning. However, the U.S. Army Chemical School at Fort McClellan, Anniston, Alabama did not reopen until 1980.

Restructuring, 1980–1989

By 1982 the Chemical Corps was running smoothly once again. In an effort to hasten chemical defense capabilities the corps restructured its doctrine, modernized its equipment, and altered its force structure. This shift led to every unit in the army having chemical specialists in-house by the mid-1980s. Between 1979 and 1989 the Army established 28 active duty chemical defense companies.Southwest Asia

After Invasion of Kuwait, Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990 and much of the world responded by amassing military assets in the region, the United States Army faced the possibility of experiencing chemical or biological (CB) attack.Taylor, Eric R.Are Our Troops Ready for Biological and Chemical Attacks?

, ''Policy Analysis'', CATO Institute, 5 February 2003, accessed 12 October 2008. The possibility of CB attack forced the army to respond with NBC defense crash courses in theater. Troops deployed to the Gulf with protective masks at the ready, protective clothing was made available to those troops whose vicinity to the enemy or mission required it. Large scale drills were conducted in the desert to better acclimatize troops to wearing the bulky protective clothing (called MOPP (protective gear), MOPP gear) in hot weather conditions.Hammond, James W. ''Poison Gas: The Myth Versus Reality'',

Google Books

, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, (), page 91. Though Saddam Hussein had renounced the use of chemical weapons in 1989, many did not believe he would really honor that during a conflict with the United States and the broader coalition forces. As American troops headed to the desert, analysts speculated about their vulnerability to CB attack. Although the location of Hussein's chemical munitions was unknown, their existence was never doubted. Gulf War I was fought without the Iraqi Army unleashing chemical or biological munitions; Eric R. Taylor, of the CATO Institute, maintained that the effective, U.S. threat of nuclear retaliation halted Hussein from employing his chemical weapons. The locations of many of Iraq's chemical stockpiles were never uncovered and there is widespread speculation that U.S. troops were exposed to chemical munitions while destroying weapons caches, particularly near the Khamisiyah storage site.Director of Central Intelligence, DCI Persian Gulf War Illnesses Task Force.

Khamisiyah: A Historical Perspective on Related Intelligence

, 9 April 1997, accessed 12 October 2008. After the war, analysis suggested the chemical defense capabilities of U.S. forces were woefully inadequate during and after the conflict. In addition, some experts, such as Jonathan B. Tucker, suggest that the Iraqis did indeed employ chemical weapons during the war.Jonathan B. Tucker, Tucker, Jonathan B.

Evidence Iraq Used Chemical Weapons During the 1991 Persian Gulf War

, ''The Nonproliferation Review'', Spring/Summer 1997, accessed 12 October 2008.

1990–present

As a result of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack, sarin gas attack on a Tokyo subway and the growing concern about a terrorist chemical attack, the U.S. Congress passed laws to implement a program to train civilian, law enforcement, and fire agencies on responding to incidents involving chemical agents. Further, United States Army Reserve chemical units began fielding equipment and training Soldiers to perform mass casualty decontamination operations. A 1996 Government Accountability Office, United States Government Accountability Office report concluded that U.S. troops remained highly vulnerable to attack from both chemical and biological agents. The report blamed the U.S. Department of Defense for failure to address shortcoming identified five years earlier during combat in the Persian Gulf War. These shortcomings included inadequate training, a lack of decontamination kits and other equipment, and vaccine shortages.Chemical and Biological Defense: Emphasis Remains Insufficient to Resolve Continuing Problems, United States General Accounting Office, via Federation of American Scientists, 12 March 1996, accessed 12 October 2008.

Organization and mission

From 1952 until 1999 the Chemical Corps School was located at Fort McClellan. Since its closure due to Base Realignment and Closure in 1999, the Army's Chemical Corps and the United States Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) School are located at Fort Leonard Wood (military base), Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. There are approximately 22,000 members of the Chemical Corps in the U.S. Army, spread among the Active, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard. The school trains officers and enlisted personnel in CBRN warfare and defense with a mission is "To protect the force and allow the Army to fight and win against a CBRN (weapon), CBRN threat. Develop doctrine, equipment and training for CBRN defense which serve as a deterrent to any adversary possessing weapons of mass destruction. Provide the Army with the combat multipliers of smoke, obscurant, and flame capabilities."Traditions

Branch insignia

," ''Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army'', The Institute of Heraldry. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

Regimental insignia

The regimental motto, ''Elementis Regamus Proelium'' translates to: "We rule the battle by means of the elements." The Chemical Corps regimental insignia was approved on 2 May 1986. The insignia consists of a 1.2 inch shield of gold and blue emblazoned with a dragon and a tree. The shield is enclosed on three sides by a blue ribbon with ''Elementis regamus proelium'' written around it in gold lettering. The phrase translates to: "We rule the battle through the elements.". The regimental insignia incorporates specific symbolism in its design. The colors, gold and blue, are the colors of the Chemical Corps, while the tree's trunk is battle scarred, a reference to the historical beginnings of U.S. chemical warfare, battered tree trunks were often the only reference points that chemical mortar teams had across no man's land during World War I.Regimental Crest

The regimental motto, ''Elementis Regamus Proelium'' translates to: "We rule the battle by means of the elements." The Chemical Corps regimental insignia was approved on 2 May 1986. The insignia consists of a 1.2 inch shield of gold and blue emblazoned with a dragon and a tree. The shield is enclosed on three sides by a blue ribbon with ''Elementis regamus proelium'' written around it in gold lettering. The phrase translates to: "We rule the battle through the elements.". The regimental insignia incorporates specific symbolism in its design. The colors, gold and blue, are the colors of the Chemical Corps, while the tree's trunk is battle scarred, a reference to the historical beginnings of U.S. chemical warfare, battered tree trunks were often the only reference points that chemical mortar teams had across no man's land during World War I.Regimental Crest," ''U.S. Army Chemical School'', United States Army — Fort Leonard Wood. Retrieved 14 October 2007. The tree design was taken from the coat of arms of the First Gas Regiment. The mythical chlorine breathing green dragon symbolizes the first use of chemical weapons in warfare (chlorine). Individual Chemical Corps soldiers are often referred to as "Dragon Soldiers."Mauroni, Albert J. ''Where are the WMDs?''

Google Books

, Naval Institute Press, 2006, (), p. 4.

Regimental association

The Chemical Corps Regimental Association operates the "Chemical Corps Hall of Fame". The list includes soldiers from many different eras of the Chemical Corps history, including Amos Fries, Earl J. Atkisson, and William L. Sibert.," ''Chemical Corps Regimental Association'', official site. Retrieved 27 November 2007. The organization conducts annual inductions, and the honor is considered the highest offered by the corps.Whitacre, Kimberly S. and Jones, Ricardo.

2006 U.S. Army Chemical Corps Hall of Fame Inductees

", ''Army Chemical Review'', July—December 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

Notable members

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Baseball Hall of Fame baseball player, manager, and executive Branch Rickey served in the 1st Gas Regiment during World War I. Rickey spent over four months as a member of the CWS. Other Hall of Famers also served in the CWS during World War I, among them Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson; Mathewson suffered lung damage after inhaling gas in a training accident, which contributed to his later death from tuberculosis. Robert S. Mulliken served in the CWS making poison gas during World War I, and he later earned the Nobel Prize in 1966 for his work on the electronic structure of molecules.Notes

Further reading

*Faith, Thomas I. ''Behind the Gas Mask: The U.S. Chemical Warfare Service in War and Peace.'' Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2014. *Marsh, Hannah. "Memory in World War I American museum exhibits" (Master of Arts thesis, Kansas State University, 2015online

, about the Chemical Corps Museum at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri *Mims, Samuel E. "Survey: Perceptions About the Army Chemical Corps"

Abstract

, April 1992, ''United States Army War College, Army War College'': Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, accessed 12 October 2008.

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Chemical Corps, United States Army 1918 establishments in the United States Army units and formations of the United States in World War I Branches of the United States Army Chemical warfare Military units and formations established in 1918 Military units and formations of the United States Army in the Vietnam War Military units and formations of the United States Army in World War II Organizations based in Missouri United States Army units and formations in the Korean War