Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

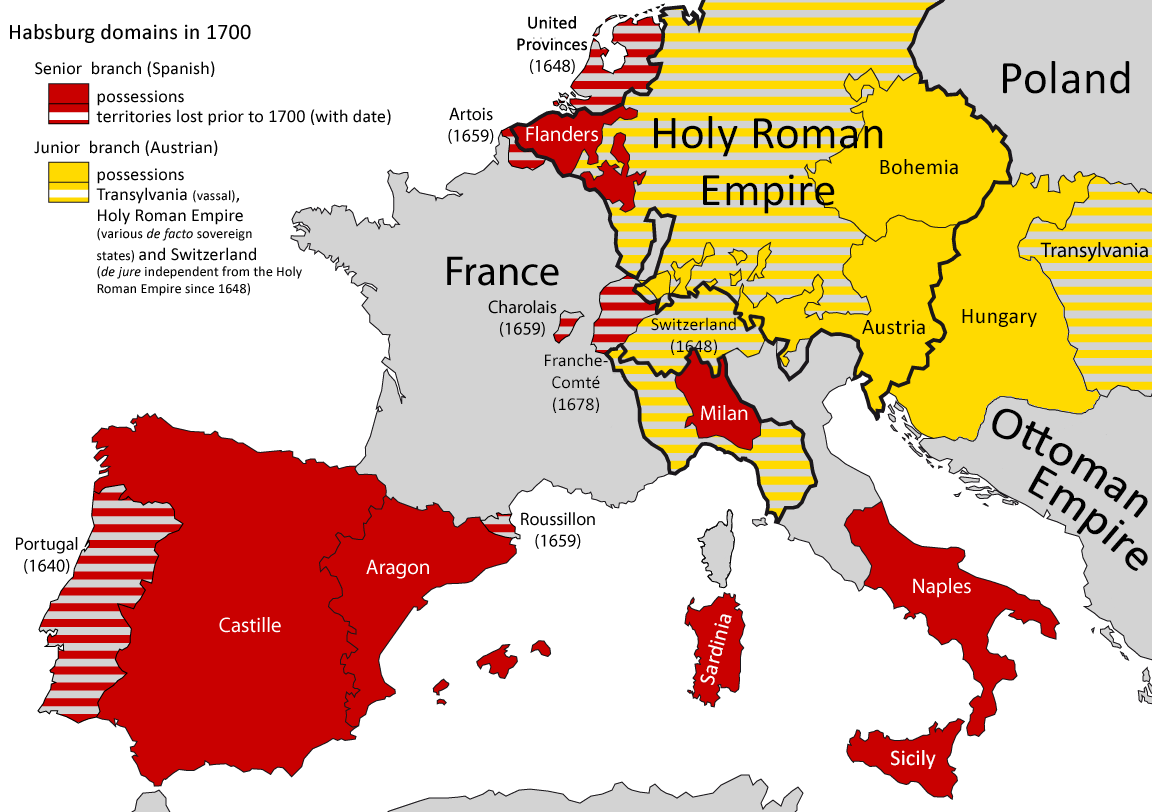

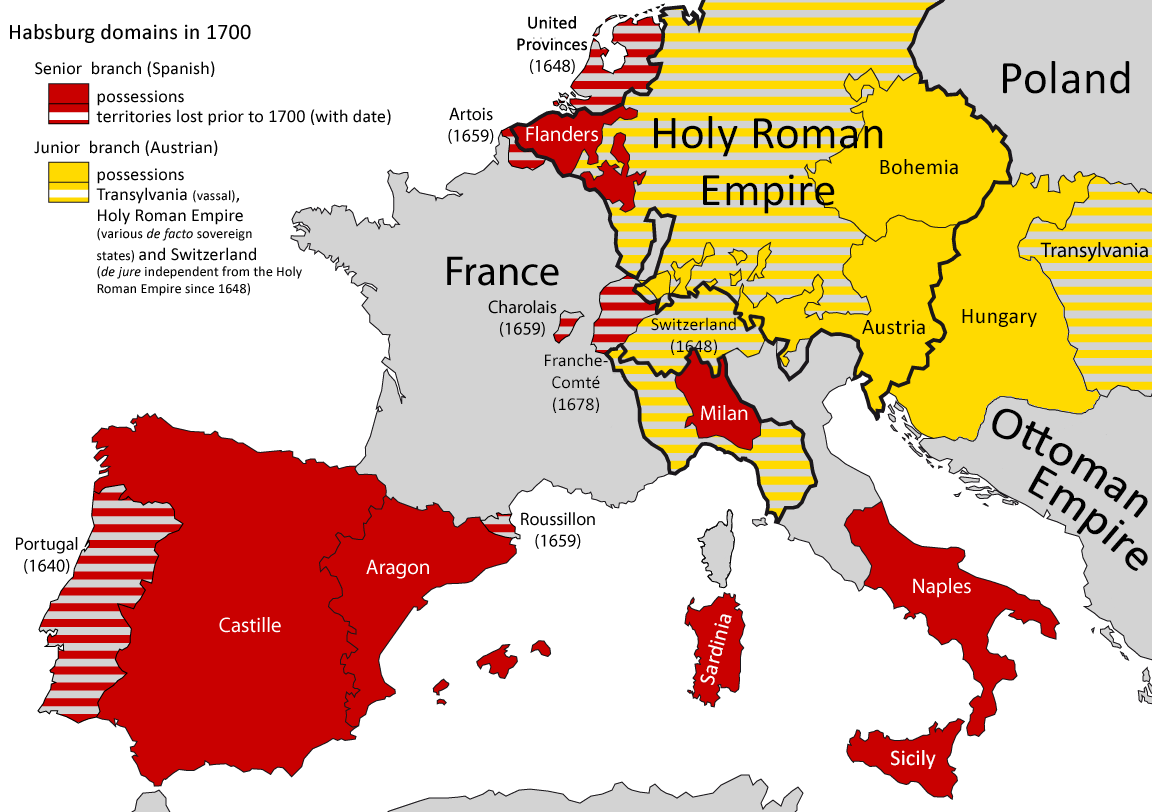

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was

Charles of

Charles of

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

and Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, thos ...

from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

( Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary, wife of Maximilian I of Austri ...

as titular Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy (french: duc de Bourgogne) was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by France in 1477, and later by Holy Roman Emperors and Kings of Spain from the House of Habsburg ...

from 1506 to 1555. He was heir to and then head of the rising House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

during the first half of the 16th century, his dominions in Europe included the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, extending from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

to northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

with direct rule over the Austrian hereditary lands and the Burgundian Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and in parts of France and Germany. The Duke of Burgundy was originally a member of the Hous ...

, and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

with its southern Italian possessions of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

. He oversaw both the continuation of the long-lasting Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spain began colonizing the Americas under the Crown of Castile and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire, with the exception of Brazil, British America, and some small regions ...

and the short-lived German colonization of the Americas

German attempts at the colonization of the Americas consisted of German Venezuela (german: Klein-Venedig, also german: Welser-Kolonie), St. Thomas and Crab Island in the 16th and 17th centuries.

History

Klein-Venedig

''Klein-Venedig'' ( ...

. The personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

of the European and American territories of Charles V was the first collection of realms labelled "the empire on which the sun never sets

The phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" ( es, el imperio donde nunca se pone el sol) was used to describe certain global empires that were so extensive that it seemed as though it was always daytime in at least one part of its territ ...

".

Charles was born in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

to Habsburg prince Philip the Handsome

Philip the Handsome, es, Felipe, french: Philippe, nl, Filips (22 July 1478 – 25 September 1506), also called the Fair, was ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands and titular Duke of Burgundy from 1482 to 1506, as well as the first Habsburg Ki ...

(son of Maximilian I of Habsburg

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed himself Ele ...

and Mary of Burgundy

Mary (french: Marie; nl, Maria; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), nicknamed the Rich, was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy who ruled a collection of states that included the duchies of Limburg, Brabant, Luxembourg, the counties of ...

) and Joanna of Trastámara, younger child of Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain), and not expected to inherit the Iberian crowns. The ultimate heir of his four grandparents, Charles inherited all of his family dominions at a young age. After the death of his father Philip in 1506, he inherited the Burgundian states originally held by his paternal grandmother Mary. In 1516, inheriting the dynastic union formed by his maternal grandparents Isabella I and Ferdinand II, he became king of Spain as co-monarch of the Spanish kingdoms with his mother, who was deemed incapable of ruling due to mental illness. Spain's possessions at his accession also included the Castilian colonies of the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

as well as the Aragonese kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia. At the death of his paternal grandfather Maximilian in 1519, he inherited Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and was elected to succeed him as Holy Roman Emperor. He adopted the Imperial name of ''Charles V'' as his main title, and styled himself as a new Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

.

Charles V revitalized the medieval concept of universal monarchy

A universal monarchy is a concept and political situation where one monarchy is deemed to have either sole rule over everywhere (or at least the predominant part of a geopolitical area or areas) or to have a special supremacy over all other st ...

. Although his empire came to him peacefully as inheritances from strategic marriages, he spent most of his life waging war, exhausting his own royal revenues and leaving debts to his successors in his attempt to defend the integrity of the Holy Roman Empire from the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the expansion of the Muslim realms of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and in a series of wars with France. With no fixed capital city, he made 40 journeys, travelling in different entities he ruled; he spent a quarter of his reign travelling within his realms. The imperial wars were fought by German ''Landsknechte

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front line ...

'', Spanish tercios

A ''tercio'' (; Spanish for " third") was a military unit of the Spanish Army during the reign of the Spanish Habsburgs in the early modern period. The tercios were renowned for the effectiveness of their battlefield formations, forming the el ...

, Burgundian knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

, and Italian ''condottieri

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Europ ...

''. Charles V borrowed money from German and Italian bankers and, in order to repay such loans, he relied on the proto-capitalist economy of the Low Countries and on the flow of precious metal, especially silver, from Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and Peru to Spain, which caused widespread inflation. During his reign his realms expanded by the Spanish conquest of the Aztec and Inca

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

empires by the Spanish conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

es Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

and Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

, as well as the establishment of Klein-Venedig

(Little Venice) or Welserland (pronunciation �vɛl.zɐ.lant was the most significant territory of the German colonization of the Americas, from 1528 to 1546, in which the Welser banking and patrician family of the Free Imperial Cities of Augs ...

by the German Welser

Welser was a German banking and merchant family, originally a patrician family based in Augsburg and Nuremberg, that rose to great prominence in international high finance in the 16th century as bankers to the Habsburgs and financiers of C ...

family in search of the legendary El Dorado. In order to consolidate power early in his reign, Charles overcame two insurrections in Iberia (the Comuneros' Revolt and Brotherhoods' Revolt) and two German rebellions (the Knights' Revolt

The Knights' Revolt (27 August 15226 May 1523) was a short-lived revolt by several German Protestant, imperial knights, led by Franz von Sickingen, against Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. It has been called the Poor Barons' Rebellion as it inspi ...

and Great Peasants' Revolt). He suppressed a major rebellion of Spanish colonists in Peru in the 1540s.

Crowned King in Germany

This is a list of monarchs who ruled over East Francia, and the Kingdom of Germany (''Regnum Teutonicum''), from the division of the Frankish Empire in 843 and the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 until the collapse of the German Emp ...

, Charles sided with Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

and declared Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

an outlaw at the Diet of Worms (1521). The same year, Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

, surrounded by the Habsburg possessions, started a conflict in Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

that lasted until the Battle of Pavia

The Battle of Pavia, fought on the morning of 24 February 1525, was the decisive engagement of the Italian War of 1521–1526 between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg empire of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor as well as ruler of Spain, ...

(1525), which led to the French king's temporary imprisonment. The Protestant affair re-emerged in 1527 as Rome was sacked by an army of Charles's mutinous soldiers, largely of Lutheran faith. In the following years, Charles V defended Vienna from the Turks and obtained a coronation as King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader, ...

and Holy Roman Emperor from Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

. In 1535, he annexed the vacant Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan ( it, Ducato di Milano; lmo, Ducaa de Milan) was a state in northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti family, which had been ruling the city sin ...

and captured Tunis. Nevertheless, the loss of Buda during the struggle for Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and the Algiers expedition in the early 1540s frustrated his anti-Ottoman policies. Charles V had come to an agreement with Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

for the organization of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

(1545). The refusal of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

to recognize the council's validity led to a war

''A War'' () is a 2015 Danish war drama film written and directed by Tobias Lindholm, and starring Pilou Asbæk and Søren Malling. It tells the story of a Danish military company in Afghanistan that is fighting the Taliban while trying to pro ...

, won by Charles V with the imprisonment of the Protestant princes. However, Henry II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder bro ...

offered new support to the Lutheran cause and strengthened a close alliance with the Muslim sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

, the ruler of the Ottoman Empire since 1520.

Ultimately, Charles V conceded the Peace of Augsburg and abandoned his multi-national project with a series of abdications in 1556 that divided his hereditary and imperial domains between the Spanish Habsburgs, headed by his son Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, and the Austrian Habsburgs, headed by his brother Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

. Ferdinand had been archduke of Austria in Charles's name since 1521 and the designated successor as emperor since 1531. The Duchy of Milan and the Habsburg Netherlands were also left in personal union to the king of Spain, although initially also belonging to the Holy Roman Empire. The two Habsburg dynasties remained allied until the extinction of the Spanish line in 1700. In 1557, Charles retired to the Monastery of Yuste

The Monastery of Yuste is a monastery in the small village now called Cuacos de Yuste (in older works ''San Yuste'' or ''San Just'') in the province of Cáceres in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. The monastery was founded by t ...

in Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, it ...

and died there a year later.

Ancestry

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

was born on 24 February 1500 in the Prinsenhof

The Prinsenhof ("The Court of the Prince") in the city of Delft in the Netherlands is an urban palace built in the Middle Ages as a monastery. Later it served as a residence for William the Silent. William was assassinated in the Prinsenhof by ...

of Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

, a Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

city of the Burgundian Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and in parts of France and Germany. The Duke of Burgundy was originally a member of the Hous ...

, to Philip of Habsburg and Joanna of Trastámara. His father Philip, nicknamed ''Philip the Handsome'', was the firstborn son of Maximilian I of Habsburg

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed himself Ele ...

, Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, thos ...

as well as Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, and Mary the Rich, Burgundian duchess of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. Charles's mother Joanna was a younger daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

and Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain from the House of Trastámara

The House of Trastámara (Spanish, Aragonese and Catalan: Casa de Trastámara) was a royal dynasty which first ruled in the Crown of Castile and then expanded to the Crown of Aragon in the late middle ages to the early modern period.

They were a ...

. The political marriage of Philip and Joanna was first conceived in a letter sent by Maximilian to Ferdinand in order to seal an Austro-Spanish alliance, established as part of the ''League of Venice

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

Sports

* Sports league

* Rugby league, full contact footba ...

'' directed against the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

during the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

.''Emperor, a new life of Charles V'', Geoffrey Parker

From the moment he became King of the Romans (''de facto'' Crown Prince of the Holy Roman Empire) in 1486, Charles's paternal grandfather Maximilian had carried a very financially risky policy of maximum expansionism, relying mostly on the resources of the Austrian hereditary lands. Even though it is often implied (among others, by Erasmus of Rotterdam

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

) that Charles V and the Habsburgs gained their vast empire through peaceful policies (exemplified by the saying ''Bella gerant aliī, tū fēlix Austria nūbe/ Nam quae Mars aliīs, dat tibi regna Venus'' or "Let others wage war, but thou, O happy Austria, marry; for those kingdoms which Mars gives to others, Venus gives to thee.", reportedly spoken by Mathias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

), Maximilian and his descendants fought wars aplenty (Maximilian alone fought 27 wars during his four decades of ruling). His general strategy was to combine his intricate systems of alliance, wars, military threats and offers of marriage to realize his expansionist ambitions. Ultimately he succeeded in coercing Bohemia, Hungary and Poland into acquiescence in the Habsburgs' expansionist plan.

The fact that the marriages between the Habsburgs and the Trastámaras, originally conceived as a marital alliance against France, would bring the crowns of Castille and Aragon to Maximilian's male line, however, was unexpected.

The marriage contract

''Marriage Contract'' () is a 2016 South Korean television series starring Lee Seo-jin and Uee. It aired on MBC from March 5 to April 24, 2016 on Saturdays and Sundays at 22:00 for 16 episodes.

Plot

Kang Hye-soo (Uee) is a single mother who ...

between Philip and Joanna was signed in 1495, and celebrations were held in 1496. Philip was already Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy (french: duc de Bourgogne) was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by France in 1477, and later by Holy Roman Emperors and Kings of Spain from the House of Habsburg ...

, given Mary's death in 1482, and also heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

of Austria as honorific Archduke. Joanna, in contrast, was only third in the Spanish line of succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.John of Castile and older sister Isabella of Aragon. Both heirs to the crowns of Castile and Aragon John and Isabella died in 1498, and the Catholic Monarchs desired to keep the Spanish kingdoms in Iberian hands, so they designated their Portuguese grandson

In 1501, his parents Philip and Joanna left Charles in care of Philip's step-grandmother

In 1501, his parents Philip and Joanna left Charles in care of Philip's step-grandmother

The Burgundian inheritance included the

The Burgundian inheritance included the  The Spanish inheritance, resulting from a

The Spanish inheritance, resulting from a

Given the vast dominions of the House of Habsburg, Charles was often on the road and needed

Given the vast dominions of the House of Habsburg, Charles was often on the road and needed

In the Castilian ''Cortes'' of Valladolid in 1506 and of Madrid in 1510, Charles was sworn as the

In the Castilian ''Cortes'' of Valladolid in 1506 and of Madrid in 1510, Charles was sworn as the

From his maternal grandmother,

From his maternal grandmother,

After the death of his paternal grandfather,

After the death of his paternal grandfather,

Much of Charles's reign was taken up by conflicts with France, which found itself encircled by Charles's empire while it still maintained ambitions in Italy. In 1520, Charles visited

Much of Charles's reign was taken up by conflicts with France, which found itself encircled by Charles's empire while it still maintained ambitions in Italy. In 1520, Charles visited  When he was released, however, Francis had the Parliament of Paris denounce the treaty because it had been signed under duress. France then joined the

When he was released, however, Francis had the Parliament of Paris denounce the treaty because it had been signed under duress. France then joined the

p. 192

/ref>Froude (1891)

p. 35, pp. 90–91, pp. 96–97

Note: the link goes to page 480, then click the View All option In other respects, the war was inconclusive. In the

The issue of the

The issue of the  Nonetheless, Charles V kept his word and left Martin Luther free to leave the city. Frederick the Wise,

Nonetheless, Charles V kept his word and left Martin Luther free to leave the city. Frederick the Wise,

Charles's main sources of revenue were from Castile, Naples and the Low Countries, which yielded in total an annual amount of around 2.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1520s and about 4.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1540s. Ferdinand I's annual revenue totalled between 1.7 million and 1.9 million Venetian ducats (2.15–2.5 million florin or Rhine gulden). Their chief enemy, the Ottomans, had a more streamlined and profitable system, yielding in total 10 million gold ducats in 1527–1528 and also did not suffer from deficit.

He often had to depend on loans from bankers. He borrowed 28 million ducats in total during his reign, of which 5.5 million ducats came from the Fugger family, Fuggers and 4.2 million from the Welser family, Welsers of Augsburg. Other creditors were from Genoa, Antwerp and Spain.

Charles's main sources of revenue were from Castile, Naples and the Low Countries, which yielded in total an annual amount of around 2.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1520s and about 4.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1540s. Ferdinand I's annual revenue totalled between 1.7 million and 1.9 million Venetian ducats (2.15–2.5 million florin or Rhine gulden). Their chief enemy, the Ottomans, had a more streamlined and profitable system, yielding in total 10 million gold ducats in 1527–1528 and also did not suffer from deficit.

He often had to depend on loans from bankers. He borrowed 28 million ducats in total during his reign, of which 5.5 million ducats came from the Fugger family, Fuggers and 4.2 million from the Welser family, Welsers of Augsburg. Other creditors were from Genoa, Antwerp and Spain.

After his father death, Charles, as Duke of Burgundy, continued to develop the system. Behringer notes that, "Whereas the status of private mail remains unclear in the treaty of 1506, it is obvious from the contract of 1516 that the Taxis company had the right to carry mail and keep the profit as long as it guaranteed the delivery of court mail at clearly defined speeds, regulated by time sheets to be filled in by the post riders on the way to their destination. In return, imperial privileges guaranteed exemption from local taxes, local jurisdiction, and military service. 21 The terminology of the early modern communications system and the legal status of its participants were invented at these negotiations." He confirmed Jannetto's son Giovanni Battista de Tassis, Giovanni Battista as Postmaster General (''chief et maistre general de noz postes par tous noz royaumes, pays, et seigneuries'') in 1520. By Charles V's time, "the Holy Roman Empire had become the centre of the European communication(s) universe."

Charles V also inherited efficient multinational diplomatic networks from both the Trastamara and Habsburg-Burgundian dynasties. Following the example of the papal curia, in the late fifteenth century, both dynasties also began to employ permanent envoys (earlier than other secular powers). The Habsburg network developed in parallel to their postal system. Charles V combined the Spanish and the Imperial systems into one. His opponents, chiefly France, found a counterweight though, by the alliance with the Ottoman Empire, which Francis I admitted to be the only force that could prevent the Habsburgs from transforming European states into a Europe-wide empire. Moreover, Charles V's military might frightened other European rulers, thus while he was able to make the pope a reluctant agent like his grandfather Ferdinand had done, no lasting alliance could be achieved. After the Battle of Pavia, the European rulers united to prevent harsh terms from being placed upon France.

In the 1530s, in the context of the conflict between the Habsburg empire and their greatest opponent, the Ottomans, an espionage network was built by Charles and Don Alfonso Granai Castriota, the marquis of Atripalda, who conducted its operations. Naples became the main rearguard of the system. Gennaro Varriale writes that, "on the eve of the Tunis campaign, Emperor Charles V possessed a network of spies based in the

After his father death, Charles, as Duke of Burgundy, continued to develop the system. Behringer notes that, "Whereas the status of private mail remains unclear in the treaty of 1506, it is obvious from the contract of 1516 that the Taxis company had the right to carry mail and keep the profit as long as it guaranteed the delivery of court mail at clearly defined speeds, regulated by time sheets to be filled in by the post riders on the way to their destination. In return, imperial privileges guaranteed exemption from local taxes, local jurisdiction, and military service. 21 The terminology of the early modern communications system and the legal status of its participants were invented at these negotiations." He confirmed Jannetto's son Giovanni Battista de Tassis, Giovanni Battista as Postmaster General (''chief et maistre general de noz postes par tous noz royaumes, pays, et seigneuries'') in 1520. By Charles V's time, "the Holy Roman Empire had become the centre of the European communication(s) universe."

Charles V also inherited efficient multinational diplomatic networks from both the Trastamara and Habsburg-Burgundian dynasties. Following the example of the papal curia, in the late fifteenth century, both dynasties also began to employ permanent envoys (earlier than other secular powers). The Habsburg network developed in parallel to their postal system. Charles V combined the Spanish and the Imperial systems into one. His opponents, chiefly France, found a counterweight though, by the alliance with the Ottoman Empire, which Francis I admitted to be the only force that could prevent the Habsburgs from transforming European states into a Europe-wide empire. Moreover, Charles V's military might frightened other European rulers, thus while he was able to make the pope a reluctant agent like his grandfather Ferdinand had done, no lasting alliance could be achieved. After the Battle of Pavia, the European rulers united to prevent harsh terms from being placed upon France.

In the 1530s, in the context of the conflict between the Habsburg empire and their greatest opponent, the Ottomans, an espionage network was built by Charles and Don Alfonso Granai Castriota, the marquis of Atripalda, who conducted its operations. Naples became the main rearguard of the system. Gennaro Varriale writes that, "on the eve of the Tunis campaign, Emperor Charles V possessed a network of spies based in the

On 21 December 1507, Charles was betrothed to 11-year-old Mary Tudor, Queen of France, Mary, the daughter of King Henry VII of England and younger sister to the future King

On 21 December 1507, Charles was betrothed to 11-year-old Mary Tudor, Queen of France, Mary, the daughter of King Henry VII of England and younger sister to the future King  The marriage lasted for thirteen years, until Isabella's death in 1539. The Empress contracted a fever during the third month of her seventh pregnancy, which resulted in antenatal complications that caused her to miscarry a stillborn son. Her health further deteriorated due to an infection, and she died two weeks later on 1 May 1539, aged 35. Charles was left so grief-stricken by his wife's death that for two months he shut himself up in a monastery, where he prayed and mourned for her in solitude. Charles never recovered from Isabella's death, dressing in black for the rest of his life to show his eternal mourning, and, unlike most kings of the time, he never remarried. In memory of his wife, the Emperor commissioned the painter Titian to paint several posthumous portraits of Isabella; the finished portraits included Titian's ''Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, Portrait of Empress Isabel of Portugal'' and ''La Gloria (Titian), La Gloria''. Charles kept these paintings with him whenever he travelled, and they were among those that he brought with him after his retirement to the Monastery of Yuste in 1557. In 1540, Charles paid tribute to Isabella's memory when he commissioned the Flemish composer Thomas Crecquillon to compose new music as a memorial to her. Crecquillon composed his ''Missa 'Mort m'a privé'' in memory of the Empress. It expresses the Emperor's grief and great wish for a heavenly reunion with his beloved wife.

During his lifetime, Charles V had several nonmarital liaisons, including some that produced children. One relationship was with his step-grandmother,

The marriage lasted for thirteen years, until Isabella's death in 1539. The Empress contracted a fever during the third month of her seventh pregnancy, which resulted in antenatal complications that caused her to miscarry a stillborn son. Her health further deteriorated due to an infection, and she died two weeks later on 1 May 1539, aged 35. Charles was left so grief-stricken by his wife's death that for two months he shut himself up in a monastery, where he prayed and mourned for her in solitude. Charles never recovered from Isabella's death, dressing in black for the rest of his life to show his eternal mourning, and, unlike most kings of the time, he never remarried. In memory of his wife, the Emperor commissioned the painter Titian to paint several posthumous portraits of Isabella; the finished portraits included Titian's ''Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, Portrait of Empress Isabel of Portugal'' and ''La Gloria (Titian), La Gloria''. Charles kept these paintings with him whenever he travelled, and they were among those that he brought with him after his retirement to the Monastery of Yuste in 1557. In 1540, Charles paid tribute to Isabella's memory when he commissioned the Flemish composer Thomas Crecquillon to compose new music as a memorial to her. Crecquillon composed his ''Missa 'Mort m'a privé'' in memory of the Empress. It expresses the Emperor's grief and great wish for a heavenly reunion with his beloved wife.

During his lifetime, Charles V had several nonmarital liaisons, including some that produced children. One relationship was with his step-grandmother,

File:Anthonis Mor - Margaret, Duchess of Parma - WGA16182.jpg,

File:John of Austria portrait.jpg,

The most famous—and only public—abdication took place a year later, on 25 October 1555, when Charles announced to the States General of the Netherlands (reunited in the great hall where he was emancipated exactly forty years before by Emperor Maximilian) his abdication in favour of his son of those territories as well as his intention to step down from all of his positions and retire to a monastery. During the ceremony, the gout-afflicted Emperor Charles V leaned on the shoulder of his advisor William the Silent and, crying, pronounced his resignation speech:

The most famous—and only public—abdication took place a year later, on 25 October 1555, when Charles announced to the States General of the Netherlands (reunited in the great hall where he was emancipated exactly forty years before by Emperor Maximilian) his abdication in favour of his son of those territories as well as his intention to step down from all of his positions and retire to a monastery. During the ceremony, the gout-afflicted Emperor Charles V leaned on the shoulder of his advisor William the Silent and, crying, pronounced his resignation speech:

He concluded the speech by mentioning his voyages: ten to the Low Countries, nine to Germany, seven to Spain, seven to Italy, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa. His last public words were, "My life has been one long journey."

With no fanfare, in 1556 he finalised his abdications. On 16 January 1556, he gave Spain and the Spanish Empire in the Americas to Philip. On 27 August 1556, he abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor in favour of his brother Ferdinand, elected King of the Romans in 1531. The succession was recognized by the prince-electors assembled at Frankfurt only in 1558, and by the Pope only in 1559. The Imperial abdication also marked the beginning of Ferdinand's legal and suo jure rule in the Austrian possessions, that he governed in Charles's name since 1521–1522 and were attached to Hungary and Bohemia since 1526.

According to scholars, Charles decided to abdicate for a variety of reasons: the religious division of Germany sanctioned in 1555; the state of Spanish finances, bankrupted with inflation by the time his reign ended; the revival of Italian Wars with attacks from Henri II of France; the never-ending advance of the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and central Europe; and his declining health, in particular attacks of gout such as the one that forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz where he was later defeated.

He concluded the speech by mentioning his voyages: ten to the Low Countries, nine to Germany, seven to Spain, seven to Italy, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa. His last public words were, "My life has been one long journey."

With no fanfare, in 1556 he finalised his abdications. On 16 January 1556, he gave Spain and the Spanish Empire in the Americas to Philip. On 27 August 1556, he abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor in favour of his brother Ferdinand, elected King of the Romans in 1531. The succession was recognized by the prince-electors assembled at Frankfurt only in 1558, and by the Pope only in 1559. The Imperial abdication also marked the beginning of Ferdinand's legal and suo jure rule in the Austrian possessions, that he governed in Charles's name since 1521–1522 and were attached to Hungary and Bohemia since 1526.

According to scholars, Charles decided to abdicate for a variety of reasons: the religious division of Germany sanctioned in 1555; the state of Spanish finances, bankrupted with inflation by the time his reign ended; the revival of Italian Wars with attacks from Henri II of France; the never-ending advance of the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and central Europe; and his declining health, in particular attacks of gout such as the one that forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz where he was later defeated.

File:CoA Carlos I de España.svg, Coat of arms of King Charles I of Spain before becoming emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

File:Greater Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor (1530-1556).svg, Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor.

File:Coat of arms of Charles, Infant of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy.png, Arms of Charles, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, KG at the time of his installation as a knight of the Order of the Garter, Most Noble Order of the Garter.

File:Royal Bend of Charles V.svg, Variant of the Royal Bend of Castile used by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Charles V has traditionally attracted considerable scholarly attention. There are differences among historians regarding his character, his rule and achievements (or failures) in the countries in his personal empire as well as various social movements and wider problems associated with his reign. Historically seen as a great ruler by some or a tragic failure of a politician by others, he is generally seen by modern historians as an overall capable politician, a brave and effective military leader, although his political vision and financial management tend to be questioned. References to Charles in popular culture include a large number of legends and folk tales; literary renderings of historical events connected to his life and romantic adventures, his relationship to Flanders, and his abdication; and products marketed in his name.

Charles V as a ruler has been commemorated over time in many parts of Europe. An imperial resolution of Franz Joseph I of Austria, dated 28 February 1863, included Charles V in the list of the "''most famous Austrian rulers and generals worthy of everlasting emulation''", and honored him with a life-size statue, made by the Bohemian sculptor Emanuel Max Ritter von Wachstein, located at the Museum of Military History, Vienna. The 400th anniversary of his death, celebrated in 1958 in Francoist Spain, brought together the local National Catholicism, national catholic intelligentsia and a number of European (Catholic) conservative figures, underpinning an imperial nostalgia for Charles V's Europe and the ''Universitas Christiana'', also propelling a peculiar brand of europeanism. In 2000, celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Charles's birth took place in Belgium.

Charles V has traditionally attracted considerable scholarly attention. There are differences among historians regarding his character, his rule and achievements (or failures) in the countries in his personal empire as well as various social movements and wider problems associated with his reign. Historically seen as a great ruler by some or a tragic failure of a politician by others, he is generally seen by modern historians as an overall capable politician, a brave and effective military leader, although his political vision and financial management tend to be questioned. References to Charles in popular culture include a large number of legends and folk tales; literary renderings of historical events connected to his life and romantic adventures, his relationship to Flanders, and his abdication; and products marketed in his name.

Charles V as a ruler has been commemorated over time in many parts of Europe. An imperial resolution of Franz Joseph I of Austria, dated 28 February 1863, included Charles V in the list of the "''most famous Austrian rulers and generals worthy of everlasting emulation''", and honored him with a life-size statue, made by the Bohemian sculptor Emanuel Max Ritter von Wachstein, located at the Museum of Military History, Vienna. The 400th anniversary of his death, celebrated in 1958 in Francoist Spain, brought together the local National Catholicism, national catholic intelligentsia and a number of European (Catholic) conservative figures, underpinning an imperial nostalgia for Charles V's Europe and the ''Universitas Christiana'', also propelling a peculiar brand of europeanism. In 2000, celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Charles's birth took place in Belgium.

Unusually among major European monarchs, Charles V discouraged monumental depictions of himself during his lifetime.

* The Charles V Monument (Palermo), Charles V Monument in Palermo was erected in 1631 and depicts him triumphant following the Conquest of Tunis (1535), Conquest of Tunis.

* Among other posthumous depictions, there are statues of Charles on the facade of the Ghent City Hall, City Hall in

Unusually among major European monarchs, Charles V discouraged monumental depictions of himself during his lifetime.

* The Charles V Monument (Palermo), Charles V Monument in Palermo was erected in 1631 and depicts him triumphant following the Conquest of Tunis (1535), Conquest of Tunis.

* Among other posthumous depictions, there are statues of Charles on the facade of the Ghent City Hall, City Hall in

online

* * Karl Brandi, Brandi, Karl. '' The Emperor Charles V: The growth and destiny of a man and of a world-empire'' (1939

online

* Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Grand Strategy of Charles V (1500–1558): Castile, War, and Dynastic Priority in the Mediterranean", ''Journal of Early Modern History'' (2005) 9#3 pp. 239–283

online

* Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Spanish Reformation: Institutional Reform, Taxation, and the Secularization of Ecclesiastical Properties under Charles V", ''Sixteenth Century Journal'' (2006) 37#1 pp 3–24. . * Espinosa, Aurelio. ''The Empire of the Cities: Emperor Charles V, the Comunero Revolt, and the Transformation of the Spanish System'' (2008) * * Ferer, Mary Tiffany. ''Music and Ceremony at the Court of Charles V: The Capilla Flamenca and the Art of Political Promotion'' (Boydell & Brewer, 2012). * * * Headley, John M. ''The Emperor and His Chancellor: A Study of the Imperial Chancellery under Gattinara'' (1983) covers 1518 to 1530. * Heath, Richard. ''Charles V: Duty and Dynasty: The Emperor and his Changing World 1500–1558.'' (2018) * * Kleinschmidt, Harald. ''Charles V: The World Emperor'' * Merriman, Roger Bigelow. ''The Rise of the Spanish Empire in the Old World and the New: Volume 3 The Emperor'' (1925

online

* John Julius Norwich, Norwich, John Julius. ''Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe'' (2017), popular history

excerpt

* Geoffrey Parker (historian), Parker, Geoffrey. ''Emperor: A New Life of Charles V''. New Haven: Yale University Press (2019)

excerpt

* James Reston Jr., Reston Jr., James. ''Defenders of the Faith: Charles V, Suleyman the Magnificent, and the Battle for Europe, 1520–1536'' (2009), popular history. * Richardson, Glenn. ''Renaissance Monarchy: The Reigns of Henry VIII, Francis I and Charles V'' (2002) 246 pp., covers 1497 to 1558. * Rodriguez-Salgado, Mia. ''Changing Face of Empire: Charles V, Philip II and Habsburg Authority, 1551–1559'' (1988), 375 pp. * Rosenthal, Earl E. ''Palace of Charles V in Granada'' (1986) 383 pp. * Saint-Saëns, Alain, ed. ''Young Charles V''. (New Orleans: University Press of the South, 2000). * Hugh Thomas, Baron Thomas of Swynnerton, Thomas, Hugh. ''The Golden Empire: Spain, Charles V, and the Creation of America''. New York: Random House 2010. *

text

) * Stephan Diller, Joachim Andraschke, Martin Brecht: ''Kaiser Karl V. und seine Zeit''. Ausstellungskatalog. Universitäts-Verlag, Bamberg 2000, * Alfred Kohler: ''Karl V. 1500–1558. Eine Biographie''. C. H. Beck, München 2001, * Alfred Kohler: ''Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V.'' Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, * Alfred Kohler, Barbara Haider. Christine Ortner (Hrsg): ''Karl V. 1500–1558. Neue Perspektiven seiner Herrschaft in Europa und Übersee''. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 2002, * Ernst Schulin: ''Kaiser Karl V. Geschichte eines übergroßen Wirkungsbereichs''. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, * Ferdinant Seibt: ''Karl V.'' Goldmann, München 1999, * Manuel Fernández Álvarez: ''Imperator mundi: Karl V. – Kaiser des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deutscher Nation.''. Stuttgart 1977,

Genealogy history of Charles V and his ancestors

The Life and Times of Emperor Charles V 1500–1558

The Library of Charles V preserved in the National Library of France

* [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03625a.htm ''New Advent'' biography of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor] *

Charles V and the Tiburtine Sibyl

Charles V the Habsburg emperor, video

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Charles 05, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, 1500 births 1558 deaths 16th-century Holy Roman Emperors 16th-century Aragonese monarchs 16th-century Castilian monarchs 16th-century Kings of Sicily 16th-century Roman Catholics 16th-century archdukes of Austria 16th-century Spanish monarchs 16th-century monarchs of Naples 16th-century Navarrese monarchs Aragonese infantes Burials in the Pantheon of Kings at El Escorial Castilian infantes Counts of Barcelona Counts of Burgundy Counts of Charolais Deaths from malaria Dukes of Burgundy Dukes of Milan Dukes of Montblanc Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece Infectious disease deaths in Spain Knights of Santiago Knights of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece Margraves of Namur, Charles 05 Modern child rulers Monarchs who abdicated Nobility from Ghent Princes of Asturias Rulers of the Habsburg Netherlands Spanish exploration in the Age of Discovery Spanish infantes Counts of Malta Dukes of Carniola Royal reburials

Miguel da Paz

Miguel da Paz, Hereditary Prince of Portugal and Prince of Asturias ( pt, Miguel da Paz de Trastâmara e Avis, ; es, Miguel de la Paz de Avís y Trastámara, "Michael of Peace") (23 August 1498 – 19 July 1500) was a Portuguese royal princ ...

as heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question.

...

of Spain by naming him Prince of the Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the throne of Spain. According to the Spanish Constitution ...

.

Birth and childhood

Charles's his mother went into labor at a ball in February 1500. At that point the newborn's royal prospects were relatively modest as heir to the Burgundian Habsburg realms in the Low Countries. He was named in honor of Charles "the Bold" of Burgundy, who had tried to turn the Burgundian state into a continuous territory. When Charles was born, a poet at the court reported that the people of Ghent "shouted Austria and Burgundy throughout the whole city for three hours" to celebrate his birth. Given the dynastic situation, the newborn was originallyheir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

only of the Burgundian Low Countries as the honorific Duke of Luxembourg

The territory of Luxembourg has been ruled successively by counts, dukes and grand dukes. It was part of the medieval Kingdom of Germany, and later the Holy Roman Empire until it became a sovereign state in 1815.

Counts of Luxembourg

House of A ...

and became known in his early years simply as "Charles of Ghent". He was baptized at the Church of Saint John by the Bishop of Tournai

The Diocese of Tournai is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Belgium. The diocese was formed in 1146, upon the dissolution of the Diocese of Noyon & Tournai, which had existed since the 7th Century. It is ...

: Charles I de Croÿ

Charles I de Croÿ (1455–1527), Count and later 1st Prince of Chimay, was a nobleman and politician from the Low Countries in the service of the House of Habsburg.

Career

Charles was born in the House of Croÿ as eldest son of Philip I of Croÿ ...

and John III of Glymes

John III, Lord of Bergen op Zoom or John III of Glymes (1452 – 1532, in Brussels) was a noble from the Low Countries.

He was the son of John II of Glymes and Margaret of Rouveroy and succeeded his father as Lord of Bergen op Zoom. In 1494 he ...

were his godfathers; Margaret of York

Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503)—also by marriage known as Margaret of Burgundy—was Duchess of Burgundy as the third wife of Charles the Bold and acted as a protector of the Burgundian State after his death. She was a daugh ...

and Margaret of Austria his godmothers. Charles's baptism gifts were a sword and a helmet, objects of Burgundian chivalric tradition representing, respectively, the instrument of war and the symbol of peace. The death in July 1500 of young heir presumptive Miguel de Paz to Iberian realms of his maternal grandparents meant baby Charles's future inheritance potentially expanded to include Castile, Aragon, and the overseas possessions in the Americas.

In 1501, his parents Philip and Joanna left Charles in care of Philip's step-grandmother

In 1501, his parents Philip and Joanna left Charles in care of Philip's step-grandmother Margaret of York

Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503)—also by marriage known as Margaret of Burgundy—was Duchess of Burgundy as the third wife of Charles the Bold and acted as a protector of the Burgundian State after his death. She was a daugh ...

and went to Spain. The main goal of their Spanish mission was the recognition of Joanna as Princess of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the throne of Spain. According to the Spanish Constitution ...

, given prince Miguel's death a year earlier. They succeeded despite facing some opposition from the Spanish ''Cortes'', which was reluctant to create the premises for Habsburg succession. In 1504, when her mother Isabella died, Joanna became Queen of Castile

This is a list of kings and queens of the Kingdom and Crown of Castile. For their predecessors, see List of Castilian counts.

Kings and Queens of Castile

Jiménez dynasty

House of Ivrea

The following dynasts are descendants, in the ...

. Charles only met his father again in 1503 while his mother returned in 1504 (after giving birth to Ferdinand in Spain). The Spanish Ambassador Fuensalida reported that Philip often visited and they had lots of fun. The couple's unhappy marriage and Joanna's unstable mental state however created many difficulties, making it unsafe for the children to stay with the parents. Philip was recognized king of Castile in 1506. He died shortly after, an event that was said to drive the mentally unstable Joanna into complete insanity. She was retired in isolation into a tower of Tordesillas

Tordesillas () is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain. It is located southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of . The population was c. 9,000 .

The town is located ...

. Charles's grandfather Ferdinand took control of all the Spanish kingdoms, under the pretext of protecting Charles's rights, which in reality he wanted to elude. Ferdinand's new marriage with Germaine de Foix

Ursula Germaine of Foix (french: Ursule-Germaine de Foix; ca, Úrsula Germana de Foix; ; c. 1488 – 15 October 1536) was an early modern French noblewoman from the House of Foix. By marriage to King Ferdinand II of Aragon, she was Queen of A ...

failed to produce a surviving Trastámara heir to the throne, so Charles remained the heir presumptive to the Iberian realms. With his father dead and his mother confined, Charles became Duke of Burgundy and was recognized as prince of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the monarchy of Spain, throne of Spain. According to the Sp ...

(heir presumptive of Spain) and honorific archduke (heir apparent of Austria).

His father's sister Margaret was the mother figure in his life. She was a huge influence on Charles. A canny, learned, and artistic woman, with a court that included artists Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley (between 1487 and 1491 – 6 January 1541), also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a versatile Flemish artist and representative of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, who w ...

and Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer (; ; hu, Ajtósi Adalbert; 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528),Müller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Dürers'', Walter de Gruyter. . sometimes spelled in English as Durer (without an umlaut) or Due ...

and master tapestry-maker Pieter van Aelst, she taught her nephew "above all that a court could be a salon." She saw to his education, securing as tutor Adrian of Utrecht

Pope Adrian VI ( la, Hadrianus VI; it, Adriano VI; nl, Adrianus/Adriaan VI), born Adriaan Florensz Boeyens (2 March 1459 – 14 September 1523), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 January 1522 until his d ...

, a member of the Brethren of the Common Life

The Brethren of the Common Life (Latin: Fratres Vitae Communis, FVC) was a Roman Catholic pietist religious community founded in the Netherlands in the 14th century by Gerard Groote, formerly a successful and worldly educator who had had a religio ...

, which advocated simplicity and promoted a cult of indigence and deprivation. The Brethren had many important members, including Thomas à Kempis

Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380 – 25 July 1471; german: Thomas von Kempen; nl, Thomas van Kempen) was a German-Dutch canon regular of the late medieval period and the author of ''The Imitation of Christ'', published anonymously in Latin in the N ...

. Adrian later became Pope Adrian VI. A third major influence in Charles's early life was Guillaume de Croÿ, Sieur de Chièves, who became his "governor and grand chamberlain", giving Charles a chivalrous education. He was tough taskmaster, and when questioned about it he said "Cousin, I am the defender and guardian of his youth. I do not want him to be incapable because he has not understood affairs nor been trained to work."

Inheritances

The Burgundian inheritance included the

The Burgundian inheritance included the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last House of Valois-Burgundy, Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary of Burgu ...

, which consisted of a large number of the lordships that formed the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

and covered modern-day Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

. It excluded Burgundy proper, annexed by France in 1477, with the exception of Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

. At the death of Philip in 1506, Charles was recognized Lord of the Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary, wife of Maximilian I of Austri ...

with the title of ''Charles II of Burgundy''. During his childhood and teen years, Charles lived in Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

together with his sisters Mary, Eleanor, and Isabeau at the court of his aunt Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy

Archduchess Margaret of Austria (german: Margarete; french: Marguerite; nl, Margaretha; es, Margarita; 10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530) was Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515 and again from 1519 to 1530. She was the firs ...

. William de Croÿ

William II de Croÿ, Lord of Chièvres (1458 – 28 May 1521) (also known as: Guillaume II de Croÿ, sieur de Chièvres in French; Guillermo II de Croÿ, señor de Chièvres, Xevres or Xebres in Spanish; Willem II van Croÿ, heer van Chi� ...

(later prime minister) and Adrian of Utrecht (later Pope Adrian VI

Pope Adrian VI ( la, Hadrianus VI; it, Adriano VI; nl, Adrianus/Adriaan VI), born Adriaan Florensz Boeyens (2 March 1459 – 14 September 1523), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 January 1522 until his d ...

) served as his tutors. The culture and courtly life of the Low Countries played an important part in the development of Charles's beliefs. As a member of the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriage ...

in his infancy, and later its grandmaster, Charles was educated to the ideals of the medieval knights and the desire for Christian unity to fight the infidel. The Low Countries were very rich during his reign, both economically and culturally

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human Society, societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, and habits of the ...

. Charles was very attached to his homeland and spent much of his life in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

and various Flemish cities.

The Spanish inheritance, resulting from a

The Spanish inheritance, resulting from a dynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union with only two different states that are governed under the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

Historical examples

Union of Kingdom of Arag ...

of the crowns of Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, included Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

as well as the Castilian possessions in the Americas (the Spanish West Indies

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The Indies was the d ...

and the Province of Tierra Firme

During Spain's New World Empire, its mainland coastal possessions surrounding the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico were referred to collectively as the Spanish Main. The southern portion of these coastal possessions were known as the Provi ...

) and the Aragonese kingdoms of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

. Joanna inherited these territories in 1516 while confined, allegedly because she was mentally ill. Charles, therefore, claimed the crowns for himself ''jure matris

''Jure matris'' (''iure matris'') is a Latin phrase meaning "by right of his mother" or "in right of his mother".

It is commonly encountered in the law of inheritance when a noble title or other right passes from mother to son. It is also used in ...

'', thus becoming co-monarch with Joanna with the title of ''Charles I of Castile and Aragon'' or ''Charles I of Spain''. Castile and Aragon together formed the largest of Charles's personal possessions, and they also provided a great number of generals and ''tercios

A ''tercio'' (; Spanish for " third") was a military unit of the Spanish Army during the reign of the Spanish Habsburgs in the early modern period. The tercios were renowned for the effectiveness of their battlefield formations, forming the el ...

'' (the formidable Spanish infantry of the time), while Joanna remained confined in Tordesillas

Tordesillas () is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain. It is located southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of . The population was c. 9,000 .

The town is located ...

until her death. However, at his accession to the Iberian throne, Charles was viewed as a foreign prince.History of Spain, Joseph Perez

Two rebellions, the revolt of the Germanies and the revolt of the comuneros

The Revolt of the Comuneros ( es, Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla, "War of the Communities of Castile") was an uprising by citizens of Castile against the rule of Charles I and his administration between 1520 and 1521. At its height, th ...

, contested Charles's rule in the 1520s. Following these revolts, Charles placed Spanish counselors in a position of power and spent a considerable part of his life in Castile, including his final years in a monastery. Indeed, Charles's motto "Plus Oultre" (''Further Beyond''), rendered as ''Plus Ultra

''Plus ultra'' (, , en, "Further beyond") is a Latin phrase and the national motto of Spain. A reversal of the original phrase ''non plus ultra'' ("Nothing further beyond"), said to have been inscribed as a warning on the Pillars of Herc ...

'' from the original French, became the national motto of Spain and his heir, later Philip II, was born and raised in Castile. Nonetheless, many Spaniards believed that their resources (largely consisting of flows of silver from the Americas) were being used to sustain Imperial-Habsburg policies that were not in the country's interest.

Charles inherited the Austrian hereditary lands in 1519, as ''Charles I of Austria'', and obtained the election as Holy Roman Emperor against the candidacy of the French King. Since the Imperial election, he was known as ''Emperor Charles V'' even outside of Germany and the Habsburg motto ''A.E.I.O.U.

"A.E.I.O.U." (sometimes A.E.I.O.V.) was a symbolic device coined by Emperor Frederick III (1415–1493) and historically used as a motto by the Habsburgs. One note in his notebook (discovered in 1666), though not in the same hand, explains it in ...

'' ("Austria Est Imperare Orbi Universo"; "it is Austria's destiny to rule the world") acquired political significance. Charles staunchly defended Catholicism as Lutheranism spread. Various German princes broke with him on religious grounds, fighting against him. Charles's presence in Germany was often marked by the organization of imperial diets to maintain religious and political unity.''Charles V'', Pierre Chaunu''Germany in the Holy Roman Empire'', Whaley

He was frequently in Northern Italy, often taking part in complicated negotiations with the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

s to address the rise of Protestantism. It is important to note, though, that the German Catholics supported the Emperor. Charles had a close relationship with important German families, like the House of Nassau

The House of Nassau is a diversified aristocratic dynasty in Europe. It is named after the lordship associated with Nassau Castle, located in present-day Nassau, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The lords of Nassau were originally titled "Count ...

, many of which were represented at his Imperial court. Several German princes or noblemen accompanied him in his military campaigns against France or the Ottomans, and the bulk of his army was generally composed of German troops, especially the Imperial Landsknechte

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front line ...

.

Charles never traveled to his overseas possessions in the Americas, since such a transatlantic crossing to a place not central to his political interests at the time was unthinkable. He did, however, establish strong administrative structures to rule them, including the European-based Council of the Indies

The Council of the Indies ( es, Consejo de las Indias), officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, link=no, ), was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Amer ...

in 1524 and the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

and the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

when the Aztec and Inca civilizations were conquered in his name.

Charles spoke several languages. He was fluent in French and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, his native languages. He later added an acceptable Castilian Spanish