Charles Lutwidge Dodgson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his

In 1846 Dodgson entered

In 1846 Dodgson entered

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat

In 1856, Dean

In 1856, Dean

In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend

In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

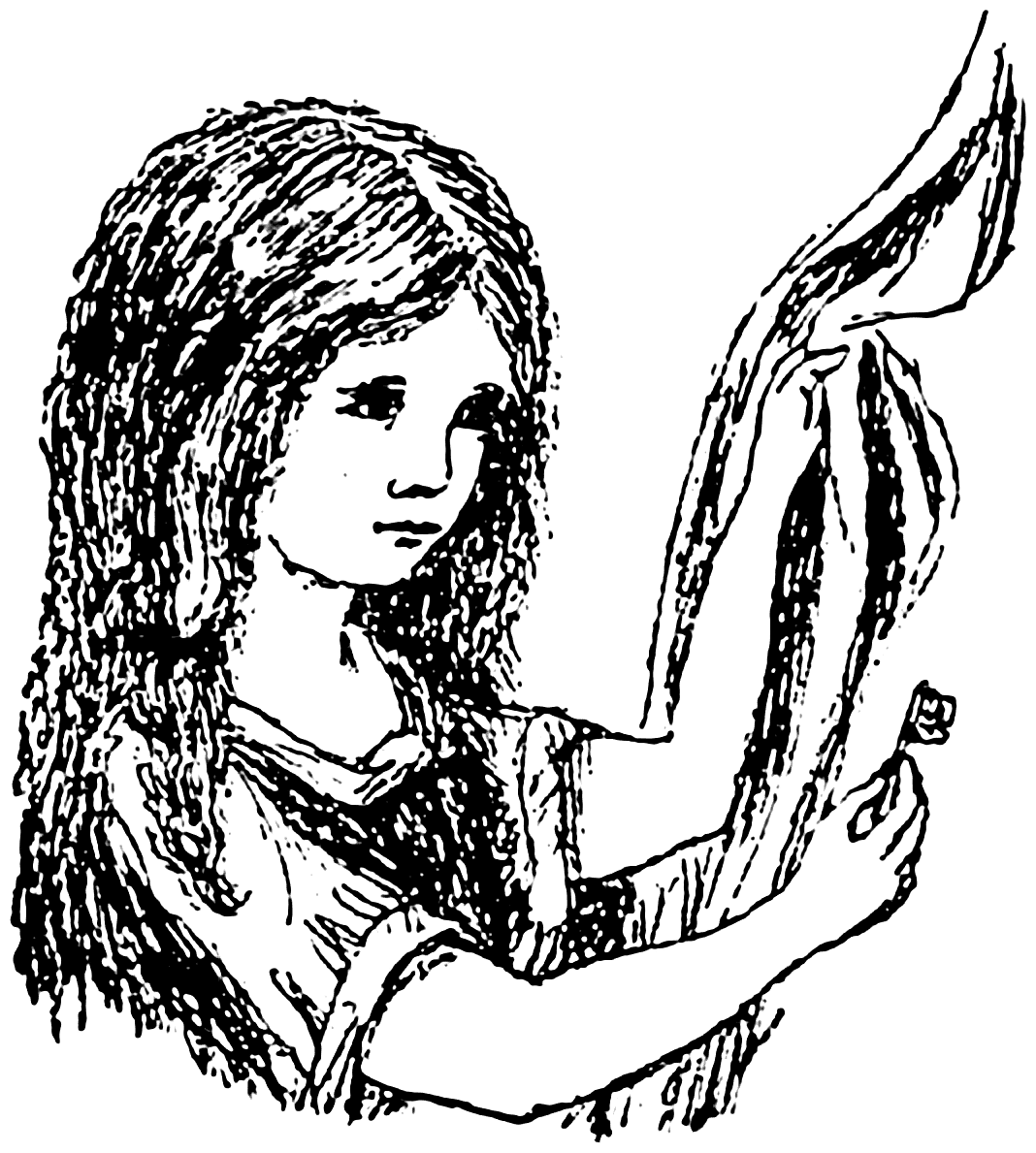

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creature ...

'' (1865) and its sequel ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

'' (1871). He was noted for his facility with word play

Word play or wordplay (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, pho ...

, logic, and fantasy. His poems '' Jabberwocky'' (1871) and ''The Hunting of the Snark

''The Hunting of the Snark'', subtitled ''An Agony in 8 Fits'', is a poem by the English writer Lewis Carroll. It is typically categorised as a nonsense poem. Written between 1874 and 1876, it borrows the setting, some creatures, and eight ...

'' (1876) are classified in the genre of literary nonsense

Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that balances elements that make sense with some that do not, with the effect of subverting language conventions or logical reasoning. Even though the most well-k ...

.

Carroll came from a family of high-church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originat ...

Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia ...

, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniq ...

, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

, the daughter of Christ Church's dean Henry Liddell

Henry George Liddell (; 6 February 1811– 18 January 1898) was dean (1855–1891) of Christ Church, Oxford, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University (1870–1874), headmaster (1846–1855) of Westminster School (where a house is now named afte ...

, is widely identified as the original inspiration for ''Alice in Wonderland'', though Carroll always denied this.

An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called "Doublets"), which he published in his weekly column for ''Vanity Fair Vanity Fair may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Literature

* Vanity Fair, a location in '' The Pilgrim's Progress'' (1678), by John Bunyan

* ''Vanity Fair'' (novel), 1848, by William Makepeace Thackeray

* ''Vanity Fair'' (magazines), the ...

'' magazine between 1879 and 1881. In 1982 a memorial stone to Carroll was unveiled at Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works.

Early life

Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English,conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, and high-church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originat ...

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

. Most of his male ancestors were army officers or Anglican clergymen. His great-grandfather, Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin

The Bishop of Elphin (; ) is an episcopal title which takes its name after the village of Elphin, County Roscommon, Ireland. In the Roman Catholic Church it remains a separate title, but in the Church of Ireland it has been united with other ...

in rural Ireland. His paternal grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies. The older of these sons, yet another Charles Dodgson, was Carroll's father. He went to Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

and then to Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniq ...

. He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead, he married his first cousin Frances Jane Lutwidge in 1830 and became a country parson. Cohen, pp. 30–35

Dodgson was born on 27 January 1832 at All Saints' Vicarage in Daresbury

Daresbury is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Halton and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. At the 2001 census it had a population of 216, increasing to 246 by the 2011 census.

History

The name means "Deor's fo ...

, Cheshire, the oldest boy and the third oldest of 11 children. When he was 11, his father was given the living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* H ...

of Croft-on-Tees

Croft-on-Tees is a village and civil parish in the Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire, England. It has also been known as Croft Spa, and from which the former Croft Spa railway station took its name. It lies north-north west of the co ...

, Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next 25 years. Charles' father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond

The Archdeacon of Richmond and Craven is an archdiaconal post in the Church of England. It was created in about 1088 within the See of York and was moved in 1541 to the See of Chester, in 1836 to the See of Ripon and after 2014 to the See of ...

and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was high-church, inclining toward Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

, an admirer of John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican priest and later as a Catholic priest and ...

and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instil such views in his children. However, Charles developed an ambivalent relationship with his father's values and with the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

as a whole.

During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven, he was reading books such as ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of t ...

''. He also spoke with a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings – that often inhibited his social life throughout his years. At the age of twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School

Richmond School & Sixth Form College, often referred to simply as Richmond School, is a Mixed-sex education, coeducational secondary school located in North Yorkshire, England. It was created by the merger of three schools, the oldest of which ...

) in Richmond, North Yorkshire

Richmond is a market town and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England, and the administrative centre of the district of Richmondshire. Historically in the North Riding of Yorkshire, it is from the county town of Northallerton and situated on ...

.

In 1846 Dodgson entered

In 1846 Dodgson entered Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. ...

, where he was evidently unhappy, as he wrote some years after leaving: "I cannot say ... that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again ... I can honestly say that if I could have been ... secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear." He did not claim he suffered from bullying, but cited little boys as the main targets of older bullies at Rugby. Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Dodgson's nephew, wrote that "even though it is hard for those who have only known him as the gentle and retiring don to believe it, it is nevertheless true that long after he left school, his name was remembered as that of a boy who knew well how to use his fists in defence of a righteous cause", which is the protection of the smaller boys.

Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby", observed mathematics master R. B. Mayor. Francis Walkingame's ''The Tutor's Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic'' – the mathematics textbook that the young Dodgson used – still survives and it contained an inscription in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, which translates to: "This book belongs to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: hands off!" Some pages also included annotations such as the one found on p. 129, where he wrote "Not a fair question in decimals" next to a question.

He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in May 1850 as a member of his father's old college, Christ Church. After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851.Clark

Clark is an English language surname, ultimately derived from the Latin language, Latin with historical links to England, Scotland, and Ireland ''clericus'' meaning "scribe", "secretary" or a scholar within a religious order, referring to someone ...

, pp. 64–65 He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" – perhaps meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

or a stroke – at the age of 47.

His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted, and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he obtained first-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in Mathematics Moderations

Honour Moderations (or ''Mods'') are a set of examinations at the University of Oxford at the end of the first part of some degree courses (e.g., Greats or '' Literae Humaniores'').

Honour Moderations candidates have a class awarded (hence the ' ...

and was soon afterwards nominated to a Studentship

A studentship is a type of academic scholarship.

United States

In the US a ''studentship'' is similar to a scholarship but involves summer work on a research project. The amount paid to the recipient is normally tax-free, but the recipient is ...

by his father's old friend Canon Edward Pusey. Collingwood, p. 52Clark

Clark is an English language surname, ultimately derived from the Latin language, Latin with historical links to England, Scotland, and Ireland ''clericus'' meaning "scribe", "secretary" or a scholar within a religious order, referring to someone ...

, p. 74 In 1854, he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, standing first on the list, and thus graduated as Bachelor of Arts. Collingwood, p. 57Wilson

Wilson may refer to:

People

*Wilson (name)

** List of people with given name Wilson

** List of people with surname Wilson

* Wilson (footballer, 1927–1998), Brazilian manager and defender

* Wilson (footballer, born 1984), full name Wilson R ...

, p. 51 He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship exam through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Cohen, p. 51Clark

Clark is an English language surname, ultimately derived from the Latin language, Latin with historical links to England, Scotland, and Ireland ''clericus'' meaning "scribe", "secretary" or a scholar within a religious order, referring to someone ...

, p. 79 Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, which he continued to hold for the next 26 years. Cohen, pp. 414–416 Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson remained at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death, including that of Sub-Librarian of the Christ Church library, where his office was close to the Deanery, where Alice Liddell lived.Leach

Leach may refer to:

* Leach (surname)

* Leach, Oklahoma, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach, Tennessee, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach Highway, Western Australia

* Leach orchid

* Leach phenotype, a mutatio ...

, Ch. 2.

Character and appearance

Health problems

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, although this might be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of 17, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or t ...

, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. In early childhood, he acquired a stammer, which he referred to as his "hesitation"; it remained throughout his life.

The stammer has always been a significant part of the image of Dodgson. While one apocryphal story says that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, there is no evidence to support this idea. Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer, while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest genetic relative was the also-extinct Rodrigues solitaire. ...

in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'', referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as a dodo, but whether or not this reference was to his stammer is simply speculation.

Dodgson's stammer did trouble him, but it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He could reportedly sing at a passable level and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was also adept at mimicry and storytelling, and reputedly quite good at charades

Charades (, ). is a parlor or party word guessing game. Originally, the game was a dramatic form of literary charades: a single person would act out each syllable of a word or phrase in order, followed by the whole phrase together, while the rest ...

.

Social connections

In the interim between his early published writings and the success of the ''Alice'' books, Dodgson began to move in thepre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jam ...

social circle. He first met John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

in 1857 and became friendly with him. Around 1863, he developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

and his family. He would often take pictures of the family in the garden of the Rossetti's house in Chelsea, London. He also knew William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism ...

, John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Baronet, ( , ; 8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) was an English painter and illustrator who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was a child prodigy who, aged eleven, became the youngest ...

, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He knew fairy-tale author George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian Congregational minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll ...

well – it was the enthusiastic reception of ''Alice'' by the young MacDonald children that persuaded him to submit the work for publication. Cohen, pp. 100–4

Politics, religion, and philosophy

In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative.Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writings of Lew ...

labels Dodgson as a Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

who was "awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors". William Tuckwell, in his ''Reminiscences of Oxford'' (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape". Dodgson was ordained a deacon in the Church of England on 22 December 1861. In ''The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll'', the editor states that "his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future." When a friend asked him about his religious views, Dodgson wrote in response that he was a member of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, but "doubt dif he was fully a 'High Churchman'". He added:

Dodgson also expressed interest in other fields. He was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a nonprofit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal. It describes itself as the "first society to co ...

, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called "thought reading". Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article " What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of ''Mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

''. The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn

Simon Blackburn (born 12 July 1944) is an English academic philosopher known for his work in metaethics, where he defends quasi-realism, and in the philosophy of language; more recently, he has gained a large general audience from his effort ...

titled "Practical Tortoise Raising".

Artistic activities

Literature

From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, contributing heavily to the family magazine ''Mischmasch

''Mischmasch'' was a periodical that Lewis Carroll wrote and illustrated for the amusement of his family from 1855 to 1862. It is notable for containing the earliest version of the poem " Jabberwocky", which Carroll would later expand and publis ...

'' and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications ''The Comic Times'' and ''The Train'', as well as smaller magazines such as the '' Whitby Gazette'' and the ''Oxford Critic''. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the ''Whitby Gazette'' or the ''Oxonian Advertiser''), but I do not despair of doing so someday," he wrote in July 1855. Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. The puppeteer uses movements of their hands, arms, or control devices such as rods or strings to move ...

plays for his siblings' entertainment, of which one has survived: ''La Guida di Bragia''.

In March 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in ''The Train'' under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll". This pseudonym was a play on his real name: ''Lewis'' was the anglicised form of ''Ludovicus'', which was the Latin for ''Lutwidge'', and ''Carroll'' an Irish surname similar to the Latin name ''Carolus'', from which comes the name ''Charles''. The transition went as follows:

"Charles Lutwidge" translated into Latin as "Carolus Ludovicus". This was then translated back into English as "Carroll Lewis" and then reversed to make "Lewis Carroll". This pseudonym was chosen by editor Edmund Yates

Edmund Hodgson Yates (3 July 183120 May 1894) was a British journalist, novelist and dramatist.

Early life

He was born in Edinburgh to the actor and theatre manager Frederick Henry Yates and was educated at Highgate School in London from 1840 to ...

from a list of four submitted by Dodgson, the others being Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U. C. Westhill, and Louis Carroll.

Alice books

In 1856, Dean

In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell

Henry George Liddell (; 6 February 1811– 18 January 1898) was dean (1855–1891) of Christ Church, Oxford, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University (1870–1874), headmaster (1846–1855) of Westminster School (where a house is now named afte ...

arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife Lorina and their children, particularly the three sisters Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. He was widely assumed for many years to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

; the acrostic

An acrostic is a poem or other word composition in which the ''first'' letter (or syllable, or word) of each new line (or paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text) spells out a word, message or the alphabet. The term comes from the F ...

poem at the end of ''Through the Looking-Glass'' spells out her name in full, and there are also many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child,Leach

Leach may refer to:

* Leach (surname)

* Leach, Oklahoma, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach, Tennessee, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach Highway, Western Australia

* Leach orchid

* Leach phenotype, a mutatio ...

, Ch. 5 "The Unreal Alice" and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of ''The Hunting of the Snark

''The Hunting of the Snark'', subtitled ''An Agony in 8 Fits'', is a poem by the English writer Lewis Carroll. It is typically categorised as a nonsense poem. Written between 1874 and 1876, it borrows the setting, some creatures, and eight ...

'', and it is not suggested that this means that any of the characters in the narrative are based on her.

Information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend to nearby Nuneham Courtenay

Nuneham Courtenay is a village and civil parish about southeast of Oxford. It occupies a pronounced section of the left bank of the River Thames.

Geography

The parish is bounded to the west by the River Thames and on other sides by field boun ...

or Godstow

Godstow is about northwest of the centre of Oxford. It lies on the banks of the River Thames between the villages of Wolvercote to the east and Wytham to the west. The ruins of Godstow Abbey, also known as Godstow Nunnery, are here. A bridge ...

.Leach

Leach may refer to:

* Leach (surname)

* Leach, Oklahoma, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach, Tennessee, an unincorporated community, United States

* Leach Highway, Western Australia

* Leach orchid

* Leach phenotype, a mutatio ...

, Ch. 4

It was on one such expedition on 4 July 1862 that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and greatest commercial success. He told the story to Alice Liddell and she begged him to write it down, and Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' in November 1864.

Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian Congregational minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll ...

read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles were rejected – ''Alice Among the Fairies'' and ''Alice's Golden Hour'' – the work was finally published as ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creature ...

'' in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. Annotated versions provide insights into many of the ideas and hidden meanings that are prevalent in these books. Critical literature has often proposed Freudian

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

interpretations of the book as "a descent into the dark world of the subconscious", as well as seeing it as a satire upon contemporary mathematical advances.

The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll" soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

herself enjoyed ''Alice in Wonderland'' so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled ''An Elementary Treatise on Determinants''. Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting "... It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred"; and it is unlikely for other reasons. As T. B. Strong comments in a '' Times'' article, "It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify heauthor of Alice with the author of his mathematical works". He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church.

Late in 1871, he published the sequel '' Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There''. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects changes in Dodgson's life. His father's death in 1868 plunged him into a depression that lasted some years.

The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876, Dodgson produced his next great work, ''The Hunting of the Snark

''The Hunting of the Snark'', subtitled ''An Agony in 8 Fits'', is a poem by the English writer Lewis Carroll. It is typically categorised as a nonsense poem. Written between 1874 and 1876, it borrows the setting, some creatures, and eight ...

'', a fantastical "nonsense" poem, with illustrations by Henry Holiday

Henry Holiday (17 June 183915 April 1927) was a British historical genre and landscape painter, stained-glass designer, illustrator, and sculptor. He is part of the Pre-Raphaelite school of art.

Life Early years and training

Holiday was born ...

, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of nine tradesmen and one beaver, who set off to find the snark. It received largely mixed reviews from Carroll's contemporary reviewers, but was enormously popular with the public, having been reprinted seventeen times between 1876 and 1908, and has seen various adaptations into musicals, opera, theatre, plays and music. Painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

reputedly became convinced that the poem was about him.

Sylvie and Bruno

In 1895, 30 years after the publication of his masterpieces, Carroll attempted a comeback, producing a two-volume tale of the fairy siblingsSylvie and Bruno

''Sylvie and Bruno'', first published in 1889, and its second volume ''Sylvie and Bruno Concluded'' published in 1893, form the last novel by Lewis Carroll published during his lifetime. Both volumes were illustrated by Harry Furniss.

The nov ...

. Carroll entwines two plots set in two alternative worlds, one set in rural England and the other in the fairytale kingdoms of Elfland, Outland, and others. The fairytale world satirizes English society, and more specifically the world of academia. ''Sylvie and Bruno'' came out in two volumes and is considered a lesser work, although it has remained in print for over a century.

Photography (1856–1880)

In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend

In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend Reginald Southey

Reginald Southey (15 September 1835 – 8 November 1899) was an English physician and inventor of ''Southey's cannula'' or ''tube'', a type of trocar used for draining oedema of the limbs.

A study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over half of his surviving work depicts young girls, though about 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing. Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, boys, and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, and trees. His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden because natural sunlight was required for good exposures.

He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as

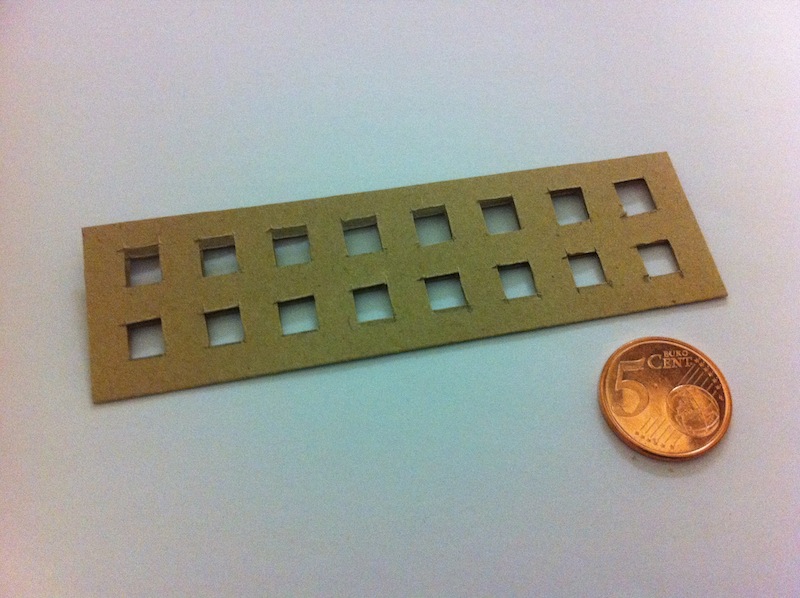

Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the

Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of

Dodgson died of

Dodgson died of

Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any

Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any

There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.

Copenhagen Street in

There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.

Copenhagen Street in

''Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection''

* ''Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing''

''Notes by an Oxford Chiel''

* ''The Principles of Parliamentary Representation'' (1884)

Dodgson, Charles L.: ''The Pamphlets of Lewis Carroll'' ** Vol. 1: ''The Oxford Pamphlets.'' 1993. ** Vol. 2: ''The Mathematical Pamphlets.'' 1994. ** Vol. 3: ''The Political Pamphlets.'' 2001. ** Vol. 4: ''The Logic Pamphlets.'' 2010 . * Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert (2016). ''The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland.'' Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674970762. * * Graham-Smith, Darien (2005). ''Contextualising Carroll'',

The Poems of Lewis Carroll

First Editions ; Physical collections

Guide to Harcourt Amory collection of Lewis Carroll

a

Houghton Library

Harvard University

Lewis Carroll

at the British Library

Lewis Carroll online exhibition

at the

Lewis Carroll Scrapbook Collection at the Library of Congress

* ; Biographical information and scholarship

Contrariwise: the Association for New Lewis Carroll Studies

— articles by leading members of the 'new scholarship'

Lewis Carroll: Logic

''

The Lewis Carroll Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carroll, Lewis 1832 births 1898 deaths British surrealist writers 19th-century English novelists 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English mathematicians 19th-century English photographers 19th-century English poets Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford 19th-century Anglican deacons Anti-vivisectionists British male poets Burials in Surrey Deaths from pneumonia in England English Anglicans English children's writers English fantasy writers English logicians English male novelists English male short story writers English novelists English philosophers English short story writers Fellows of Christ Church, Oxford Mathematics popularizers Mathematics writers People educated at Rugby School People from Cheshire People from Richmond, North Yorkshire People with speech impediment British portrait photographers Recreational mathematicians Victorian novelists Victorian poets Voting theorists Photographers from Oxfordshire Writers from Oxford Writers who illustrated their own writing 19th-century pseudonymous writers Dodgson family

John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Baronet, ( , ; 8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) was an English painter and illustrator who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was a child prodigy who, aged eleven, became the youngest ...

, Ellen Terry

Dame Alice Ellen Terry, (27 February 184721 July 1928), was a leading English actress of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born into a family of actors, Terry began performing as a child, acting in Shakespeare plays in London, and tour ...

, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, Lord Salisbury, and Alfred Tennyson.

By the time that Dodgson abruptly ceased photography (1880, after 24 years), he had established his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, created around 3,000 images, and was an amateur master of the medium, though fewer than 1,000 images have survived time and deliberate destruction. He stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was too time-consuming. He used the wet collodion process; commercial photographers who started using the dry-plate process in the 1870s took pictures more quickly. Popular taste changed with the advent of Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

, affecting the types of photographs that he produced.

Inventions

To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented "The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case" in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations up to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slipcase decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and theCheshire Cat

The Cheshire Cat ( or ) is a fictional cat popularised by Lewis Carroll in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and known for its distinctive mischievous grin. While now most often used in ''Alice''-related contexts, the association of a "C ...

on the back. It intended to organize stamps wherever one stored their writing implements; Carroll expressly notes in '' Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing'' it is not intended to be carried in a pocket or purse, as the most common individual stamps could easily be carried on their own. The pack included a copy of a pamphlet version of this lecture.

Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the

Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

writing system on a Palm

Palm most commonly refers to:

* Palm of the hand, the central region of the front of the hand

* Palm plants, of family Arecaceae

**List of Arecaceae genera

* Several other plants known as "palm"

Palm or Palms may also refer to:

Music

* Palm (ba ...

device.

He also devised a number of games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble

''Scrabble'' is a word game in which two to four players score points by placing tiles, each bearing a single letter, onto a game board divided into a 15×15 grid of squares. The tiles must form words that, in crossword fashion, read left t ...

. Devised some time in 1878, he invented the "doublet" (see word ladder), a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today, changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word. For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG. It first appeared in the 29 March 1879 issue of ''Vanity Fair Vanity Fair may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Literature

* Vanity Fair, a location in '' The Pilgrim's Progress'' (1678), by John Bunyan

* ''Vanity Fair'' (novel), 1848, by William Makepeace Thackeray

* ''Vanity Fair'' (magazines), the ...

'', with Carroll writing a weekly column for the magazine for two years; the final column dated 9 April 1881. The games and puzzles of Lewis Carroll were the subject of Martin Gardner's March 1960 Mathematical Games column in ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

''.

Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociman (a type of tricycle); fairer elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the Senior Common Room at Christ Church which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip to fasten envelopes or mount things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode ...

s for cryptography

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or '' -logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adv ...

.

He also proposed alternative systems of parliamentary representation. He proposed the so-called Dodgson's method, using the Condorcet method

A Condorcet method (; ) is an election method that elects the candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidates, that is, a candidate preferred by more voters than any others, whenever ...

. In 1884, he proposed a proportional representation system based on multi-member districts, each voter casting only a single vote, quotas as minimum requirements to take seats, and votes transferable by candidates through what is now called Liquid democracy.

Mathematical work

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, linear and matrix algebra

In abstract algebra, a matrix ring is a set of matrices with entries in a ring ''R'' that form a ring under matrix addition and matrix multiplication . The set of all matrices with entries in ''R'' is a matrix ring denoted M''n''(''R'')Lang, '' ...

, mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory. Research in mathematical logic commonly addresses the mathematical properties of forma ...

, and recreational mathematics

Recreational mathematics is mathematics carried out for recreation (entertainment) rather than as a strictly research and application-based professional activity or as a part of a student's formal education. Although it is not necessarily limited ...

, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker–Capelli theorem), probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method) and committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

s; some of this work was not published until well after his death. His occupation as Mathematical Lecturer at Christ Church gave him some financial security.

Mathematical logic

His work in the field of mathematical logic attracted renewed interest in the late 20th century. Martin Gardner's book on logic machines and diagrams and William Warren Bartley's posthumous publication of the second part of Dodgson's symbolic logic book have sparked a reevaluation of Dodgson's contributions to symbolic logic. It is recognized that in his ''Symbolic Logic Part II'', Dodgson introduced the Method of Trees, the earliest modern use of a truth tree.Algebra

Robbins' and Rumsey's investigation of Dodgson condensation, a method of evaluatingdeterminant

In mathematics, the determinant is a scalar value that is a function of the entries of a square matrix. It characterizes some properties of the matrix and the linear map represented by the matrix. In particular, the determinant is nonzero if a ...

s, led them to the alternating sign matrix

In mathematics, an alternating sign matrix is a square matrix of 0s, 1s, and −1s such that the sum of each row and column is 1 and the nonzero entries in each row and column alternate in sign. These matrices generalize permutation matrices and ...

conjecture, now a theorem.

Recreational mathematics

The discovery in the 1990s of additional ciphers that Dodgson had constructed, in addition to his "Memoria Technica", showed that he had employed sophisticated mathematical ideas in their creation.Correspondence

Dodgson wrote and received as many as 98,721 letters, according to a special letter register which he devised. He documented his advice about how to write more satisfying letters in a missive entitled " Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing".Later years

Dodgson's existence remained little changed over the last twenty years of his life, despite his growing wealth and fame. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881 and remained in residence there until his death. Public appearances included attending the West End musical ''Alice in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatur ...

'' (the first major live production of his ''Alice'' books) at the Prince of Wales Theatre on 30 December 1886. The two volumes of his last novel, ''Sylvie and Bruno

''Sylvie and Bruno'', first published in 1889, and its second volume ''Sylvie and Bruno Concluded'' published in 1893, form the last novel by Lewis Carroll published during his lifetime. Both volumes were illustrated by Harry Furniss.

The nov ...

'', were published in 1889 and 1893, but the intricacy of this work was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers; it achieved nothing like the success of the ''Alice'' books, with disappointing reviews and sales of only 13,000 copies.

The only known occasion on which he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastic, together with the Reverend Henry Liddon

Henry Parry Liddon (1829–1890), also known as H. P. Liddon, was an English theologian. From 1870 to 1882, he was Dean Ireland's Professor of the Exegesis of Holy Scripture at the University of Oxford.

Biography

The son of a naval capt ...

. He recounts the travel in his "Russian Journal", which was first commercially published in 1935. On his way to Russia and back, he also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, partitioned Poland, and France.

Death

Dodgson died of

Dodgson died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

following influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts", in Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

in the county of Surrey, just four days before the death of Henry Liddell. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. His funeral was held at the nearby St Mary's Church. His body was buried at the Mount Cemetery

Mount Cemetery, also known as Guildford Cemetery, is a cemetery in Guildford, Surrey, England. It is the location of Booker's Tower.

Guildford Cemetery is surrounded by low-density houses with gardens and a covered reservoir beyond the east c ...

in Guildford.

He is commemorated at All Saints' Church, Daresbury

All Saints' Church is in the village of Daresbury, Cheshire, England. It is known for its association with Lewis Carroll who is commemorated in its stained glass windows depicting characters from '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. It is rec ...

, in its stained glass windows depicting characters from ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''.

Controversies and mysteries

Sexuality

Some late twentieth-century biographers have suggested that Dodgson's interest in children had an erotic element, includingMorton N. Cohen

Morton Norton Cohen (27 February 192112 June 2017) was a Canadian-born American author and scholar who was a professor at City University of New York. He is best known for his studies of children's author Lewis Carroll including the 1995 biography ...

in his ''Lewis Carroll: A Biography'' (1995), Cohen, pp. 166–167, 254–255 Donald Thomas in his ''Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background'' (1995), and Michael Bakewell in his ''Lewis Carroll: A Biography'' (1996).

Cohen, in particular, speculates that Dodgson's "sexual energies sought unconventional outlets", and further writes:

Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any

Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any erotic

Eroticism () is a quality that causes sexual feelings, as well as a philosophical contemplation concerning the aesthetics of sexual desire, sensuality, and romantic love. That quality may be found in any form of artwork, including painting, scu ...

ism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229). He argues that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell and that this was the cause of the unexplained "break" with the family in June 1863, an event for which other explanations are offered. Biographers Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile (Green also edited Dodgson's diaries and papers), but they concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world. Catherine Robson refers to Carroll as "the Victorian era's most famous (or infamous) girl lover".

Several other writers and scholars have challenged the evidential basis for Cohen's and others' views about Dodgson's sexual interests. Hugues Lebailly

Hugues Lebailly is a French academic and Senior Lecturer in English Cultural Studies at the Sorbonne. He is known for his work on nineteenth-century English literature, particularly his studies of Lewis Carroll which, in combination with the work ...

has endeavoured to set Dodgson's child photography within the "Victorian Child Cult", which perceived child nudity as essentially an expression of innocence. Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers made them as a matter of course, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas card

A Christmas card is a greeting card sent as part of the traditional celebration of Christmas in order to convey between people a range of sentiments related to Christmastide and the holiday season. Christmas cards are usually exchanged during ...

s, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th- or 21st-century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time.

Karoline Leach

Karoline Leach (born 20 July 1967) is a British playwright and author, best known for her book '' In the Shadow of the Dreamchild'' (), which re-examines the life of Lewis Carroll (pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), the author of ''Alice's ...

's reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial sexuality. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea – fostered by Dodgson's various biographers – that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson "the Carroll Myth". She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several relationships with them that would have been considered scandalous by the social standards of his time. She also pointed to the fact that many of those whom he described as "child-friends" were girls in their late teens and even twenties. She argues that suggestions of paedophilia emerged only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach points to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed as the source of the dubious claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14.

In addition to the biographical works that have discussed Dodgson's sexuality, there are modern artistic interpretations of his life and work that do so as well – in particular, Dennis Potter

Dennis Christopher George Potter (17 May 1935 – 7 June 1994) was an English television dramatist, screenwriter and journalist. He is best known for his BBC television serials '' Pennies from Heaven'' (1978), ''The Singing Detective'' (198 ...

in his play ''Alice'' and his screenplay for the motion picture '' Dreamchild'', and Robert Wilson in his musical ''Alice''.

Ordination

Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

from a very early age and was expected to be ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

within four years of obtaining his master's degree, as a condition of his residency at Christ Church. He delayed the process for some time but was eventually ordained as a deacon on 22 December 1861. But when the time came a year later to be ordained as a priest, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and, initially, Dean Liddell told him that he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost certainly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted him to remain at the college in defiance of the rules. Dodgson never became a priest, unique amongst senior students of his time.

There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested that his stammer made him reluctant to take the step because he was afraid of having to preach. Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words. But Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest's orders, so it seems unlikely that his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice. Wilson also points out that the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public speakers of his day. Natural ...

, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson's great interests. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F. D. Maurice

John Frederick Denison Maurice (1805–1872), known as F. D. Maurice, was an English Anglican theologian, a prolific author, and one of the founders of Christian socialism. Since the Second World War, interest in Maurice has expanded."Frede ...

) and "alternative" religions (theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

). Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s) and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a "vile and worthless" sinner, unworthy of the priesthood and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have affected his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood.

Missing diaries

At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson's 13 diaries. The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume that the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven. Except for one page, material is missing from his diaries for the period between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old). During this period , Dodgson began experiencing great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems may have been autobiographical. Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell. However, there has never been any evidence to suggest that this was so, and a paper offers some evidence to the contrary which was discovered byKaroline Leach

Karoline Leach (born 20 July 1967) is a British playwright and author, best known for her book '' In the Shadow of the Dreamchild'' (), which re-examines the life of Lewis Carroll (pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), the author of ''Alice's ...

in the Dodgson family archive in 1996.

This paper is known as the "cut pages in diary" document, and was compiled by various members of Carroll's family after his death. Part of it may have been written at the time when the pages were destroyed, though this is unclear. The document offers a brief summary of two diary pages that are missing, including the one for 27 June 1863. The summary for this page states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson that there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family's governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, ...

, as well as about his relationship with "Ina", presumably Alice's older sister Lorina Liddell. The "break" with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip. An alternative interpretation has been made regarding Carroll's rumoured involvement with "Ina": Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell's mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is that the document seems to imply that Dodgson's break with the family was not connected with Alice at all; until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 will remain in doubt.

Migraine and epilepsy

In his diary for 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode ofmigraine

Migraine (, ) is a common neurological disorder characterized by recurrent headaches. Typically, the associated headache affects one side of the head, is pulsating in nature, may be moderate to severe in intensity, and could last from a few hou ...

with aura, describing very accurately the process of "moving fortifications" that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome.Wakeling, Edward (Ed.) "The Diaries of Lewis Carroll", Vol. 9, p. 52 Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine ''per se'', or if he may have previously had the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura called Alice in Wonderland syndrome has been named after Dodgson's little heroine because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. It is also known as micropsia

Micropsia is a condition affecting human visual perception in which objects are perceived to be smaller than they actually are. Micropsia can be caused by optical factors (such as wearing glasses), by distortion of images in the eye (such as optica ...

and macropsia

Macropsia is a neurological condition affecting human visual perception, in which objects within an affected section of the visual field appear larger than normal, causing the person to feel smaller than they actually are. Macropsia, along with its ...

, a brain condition affecting the way that objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an afflicted person may look at a larger object such as a basketball and perceive it as if it were the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson may have experienced this type of aura and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did.

Dodgson also had two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by a Dr. Morshead, Dr. Brooks, and Dr. Stedman, and they believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an "epileptiform" seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this that he had this condition for his entire life, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned. Some authors, Sadi Ranson in particular, have suggested that Carroll may have had temporal lobe epilepsy

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a chronic disorder of the nervous system which is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked focal seizures that originate in the temporal lobe of the brain and last about one or two minutes. TLE is the most common ...

in which consciousness is not always completely lost but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incident in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward". This attack was diagnosed as possibly "epileptiform" and Carroll himself later wrote of his "seizures" in the same diary.

Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson's symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf's 2010 ''The Mystery of Lewis Carroll'', is that Dodgson very likely had migraine and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information.

Legacy

There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.

Copenhagen Street in

There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.

Copenhagen Street in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

, north London is the location of the Lewis Carroll Children's Library.

In 1982, his great-nephew unveiled a memorial stone to him in Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

, Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. In January 1994, an asteroid, 6984 Lewiscarroll, was discovered and named after Carroll. The Lewis Carroll Centenary Wood near his birthplace in Daresbury opened in 2000.

Born in All Saints' Vicarage, Daresbury, Cheshire, in 1832, Lewis Carroll is commemorated at All Saints' Church, Daresbury

All Saints' Church is in the village of Daresbury, Cheshire, England. It is known for its association with Lewis Carroll who is commemorated in its stained glass windows depicting characters from '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. It is rec ...

in its stained glass windows depicting characters from ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. In March 2012, the Lewis Carroll Centre, attached to the church, was opened.

Works

Literary works

* ''La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre'' (around 1850) * "Miss Jones", comic song (1862) * ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creature ...

'' (1865)

* '' Phantasmagoria and Other Poems'' (1869)

* ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

, and What Alice Found There'' (includes " Jabberwocky" and " The Walrus and the Carpenter") (1871)

* ''The Hunting of the Snark

''The Hunting of the Snark'', subtitled ''An Agony in 8 Fits'', is a poem by the English writer Lewis Carroll. It is typically categorised as a nonsense poem. Written between 1874 and 1876, it borrows the setting, some creatures, and eight ...

'' (1876)

* '' Rhyme? And Reason?'' (1883) – shares some contents with the 1869 collection, including the long poem "Phantasmagoria"

* '' A Tangled Tale'' (1885)

* ''Sylvie and Bruno

''Sylvie and Bruno'', first published in 1889, and its second volume ''Sylvie and Bruno Concluded'' published in 1893, form the last novel by Lewis Carroll published during his lifetime. Both volumes were illustrated by Harry Furniss.

The nov ...

'' (1889)

* '' The Nursery "Alice"'' (1890)

* '' Sylvie and Bruno Concluded'' (1893)

* ''Pillow Problems'' (1893)

* '' What the Tortoise Said to Achilles'' (1895)

* ''Three Sunsets and Other Poems'' (1898)

* ''The Manlet'' (1903)''The Hunting of the Snark and Other Poems and Verses'', New York: Harper & Brothers, 1903

Mathematical works