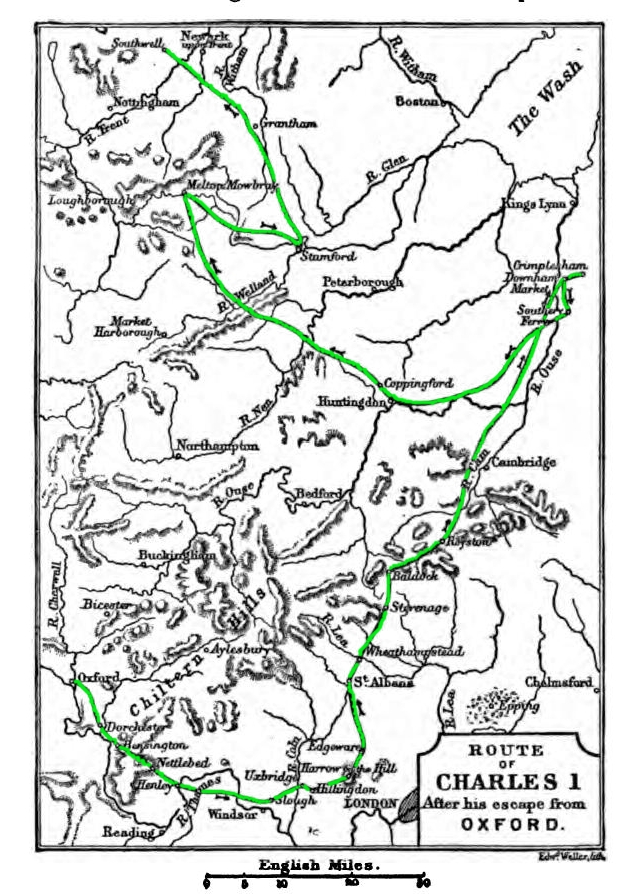

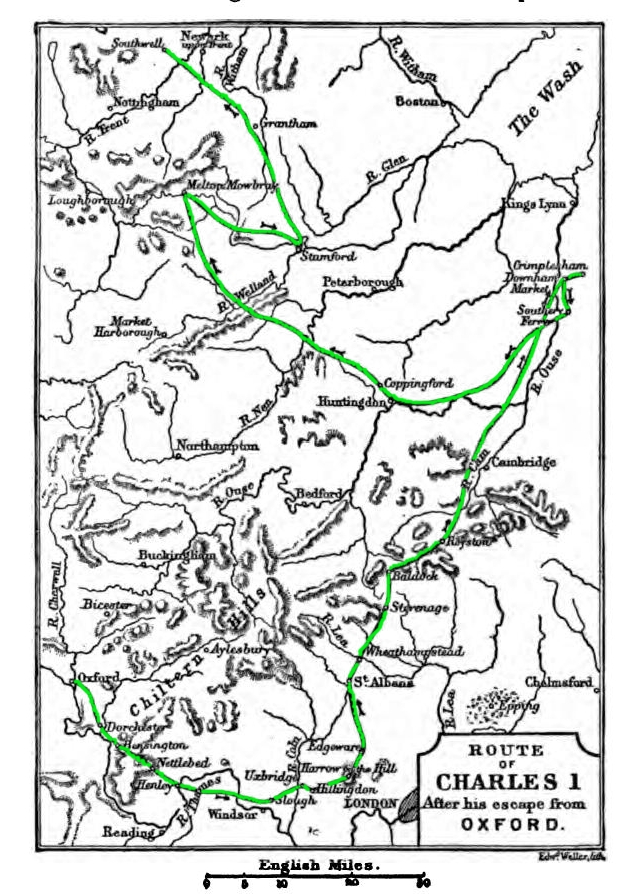

Charles I's journey from Oxford to the Scottish army camp near Newark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At Kelham House, Charles was closely watched by a guard dignified by the name of "a guard of honour" while communications were passing with Parliament and negotiations were proceeding between the English and Scottish Commissioners, who met for the purpose in the fields between Kelham and Farndon, an area called Faringdon. Montreuil, Ashburnham, and Hudson were still there, and from Ashburnham's narrative, it seems that Charles felt it wise to try the effect of a little negotiation on his own account. Ashburnham says "the King, recognising his difficulty, turned his thoughts another way, and resolved to come to the English if terms could be arranged".

Ashburnham took steps to effect this, nominating as negotiators Lord Belasyse, governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont (MP), and requested that they communicate with him, but Lord Belasyse told him, when they conversed together after the surrender of Newark, that Pierrepont "would by no means admit any discourse with me in the condition I then stood, the action of waiting on the King to the Scots army rendering me more obnoxious to the Parliament than any man living, and so those thoughts of his Majesty going to the English vanished".

If Ashburnham had succeeded in his negotiations at Kelham, the whole course of events would have been changed. As it was, the Scots held their prize securely. In the records of the House of Lords, there is a document signed by eight noblemen who had heard of the jealous way in which the King was watched, protesting against "strict guard being kept by the Scots army about the house where the King then was", and none being suffered to have access to his person without their permission.

At Kelham House, Charles was closely watched by a guard dignified by the name of "a guard of honour" while communications were passing with Parliament and negotiations were proceeding between the English and Scottish Commissioners, who met for the purpose in the fields between Kelham and Farndon, an area called Faringdon. Montreuil, Ashburnham, and Hudson were still there, and from Ashburnham's narrative, it seems that Charles felt it wise to try the effect of a little negotiation on his own account. Ashburnham says "the King, recognising his difficulty, turned his thoughts another way, and resolved to come to the English if terms could be arranged".

Ashburnham took steps to effect this, nominating as negotiators Lord Belasyse, governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont (MP), and requested that they communicate with him, but Lord Belasyse told him, when they conversed together after the surrender of Newark, that Pierrepont "would by no means admit any discourse with me in the condition I then stood, the action of waiting on the King to the Scots army rendering me more obnoxious to the Parliament than any man living, and so those thoughts of his Majesty going to the English vanished".

If Ashburnham had succeeded in his negotiations at Kelham, the whole course of events would have been changed. As it was, the Scots held their prize securely. In the records of the House of Lords, there is a document signed by eight noblemen who had heard of the jealous way in which the King was watched, protesting against "strict guard being kept by the Scots army about the house where the King then was", and none being suffered to have access to his person without their permission.

Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of Scotland, but after ...

left Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

on 27 April 1646 and travelled by a circuitous route through enemy-held territory to arrive at the Scottish army camp located close to Southwell near Newark-on-Trent

Newark-on-Trent or Newark () is a market town and civil parish in the Newark and Sherwood district in Nottinghamshire, England. It is on the River Trent, and was historically a major inland port. The A1 road bypasses the town on the line ...

on 5 May 1646. He undertook this journey because military Royalism

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of govern ...

was all but defeated. It was only a matter of days before Oxford (the Royalist First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Angl ...

capital) would be fully invested

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

and would fall to the English Parliamentarian New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

commanded by Lord General Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

(see Third Siege of Oxford). Once fully invested it was unlikely that Charles would be able to leave Oxford without being captured by soldiers of the New Model Army. Charles had been in contact with the various parties that were fielding armies against him seeking a political compromise. In late April he thought that the Scottish Presbyterian party were offering him the most acceptable terms, but to gain their protection and finalise an agreement Charles had to travel to the nearest Scottish army, and that was the one besieging the Royalist held city of Newark. Once he had arrived at his destination he was put under close guard in Kelham House.

Prelude

Towards the end of theFirst English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Angl ...

, Charles I had continued to contact the parties that were opposed to him, hoping to split them apart and gain politically what he was losing militarily.

When it looked likely that the Royalists (Cavalier

The term Cavalier () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of King Charles I and his son Charles II of England during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration (1642 – ). ...

s) would lose the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, the Scots, who were then allied with the English Parliamentarians (Roundhead

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

s), looked to Cardinal Mazarin

Cardinal Jules Mazarin (, also , , ; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino () or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis X ...

, by then the chief minister of France, for help in securing Charles I's position as king, but on terms acceptable to the Scots. In response, Mazarin appointed Jean de Montreuil (or Montereul) as French resident in Scotland. He was to act as a go-between and in doing so he was able to inform Cardinal Mazarin of the political machinations of the various parties in the civil war.

Montereul arrived in London in August 1645. Once there he opened a dialogue with English Presbyterians such as the Earl of Holland

Earl of Holland was a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1624 for Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington. He was the younger son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick, and had already been created Baron Kensington in 1623, also in the ...

who were sympathetic to the Scots who too were Presbyterians and formally allied with the Roundheads through the Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

, but which was disliked by non-Presbyterian Roundheads such as Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

and other religious Independents. There were Scottish commissioners in London who were looking after Scottish interests in the alliance and during talks with them and English Presbyterians, the idea arose that if Charles I were to place himself under the protection of the Scottish army, then the Presbyterian party could advance their interests.

Montreuil strived to extract from the Scottish Commissioners

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissioner has evolved to in ...

to the Committee of Both Kingdoms

The Committee of Both Kingdoms, (known as the Derby House Committee from late 1647), was a committee set up during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by the Parliamentarian faction in association with representatives from the Scottish Covenanters, aft ...

(the body set up to oversee the Solemn League and Covenant)—most of whom were usually located in London—the most moderate terms upon which they would receive Charles: accept three proposition touching on the Church, the militia and Ireland, and sign the Covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

. If Charles accepted those terms, they would intercede with English Parliament and banish only five or six prominent Royalists. Montreuil told Sir Robert Moray

Sir Robert Moray (alternative spellings: Murrey, Murray) FRS (1608 or 1609 – 4 July 1673) was a Scottish soldier, statesman, diplomat, judge, spy, and natural philosopher. He was well known to Charles I and Charles II, and to the French ...

—who was delegated to act for the Earl of Loudoun

Earl of Loudoun (pronounced "loud-on" ), named after Loudoun in Ayrshire, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1633 for John Campbell, 2nd Lord Campbell of Loudoun, along with the subsidiary title Lord Tarrinzean and Mauchlin ...

( High Chancellor of Scotland) in his absence from London and continued to be his delegate upon his return—that Charles would not accept those terms; he obtain a modified Scottish offer on 16 March from Sir Robert Moray, in which the Scots would instead be satisfied with a promise from Charles to accept the church settlement which had already been made by the English and Scottish parliaments, and that Charles was to express his general agreement of the Covenant in letters to the two parliaments in which he accepted the church settlement.

However, the late Victorian historian S. R. Gardiner

Samuel Rawson Gardiner (4 March 1829 – 24 February 1902) was an English historian, who specialized in 17th-century English history as a prominent foundational historian of the Puritan revolution and the English Civil War.

Life

The son of ...

suggests that Montreuil did not have a full understanding of Charles' mind. He would promise anything, providing the wording could be so construed by Charles that he could disregard it in the future, and consequently Charles would at this juncture never agree to wording that was an unambiguous legal contract.

On 17 March, Montreuil set out for Oxford, the King's headquarters. Along with the offer, he carried intelligence that the English Presbyterians would field an army of 25,000 men to support the Scots if the Independents in the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

tried to oppose the reconciliation.

Gardiner wrote:

Since he had received Montreuil's communication, the Scots had been out of favour with him, and on 23 March, upon the arrival of the bad news of the defeat of the last Royalist field army at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold, he despatched a request to the English Parliament for permission to return to Westminster, on the understanding that an act of oblivion was to be passed and all sequestrations to be reversed. Even had this offer been straightforward, it implied that the central achievement of his opponents in the winning the war should be set aside, and that Charles should be allowed to step back on the throne, free to refuse to assent to any legislation which displeased him. This proposition was rejected by the English Parliament and the Scots. All Charles had achieved by this proposal was to reconcile the factions opposed to him, so thwarting his tactics of division.

On 27 March, Montreuil, in the king's name, pressured the Scots for a reply. They informed Montreuil that they would not accept Charles' terms, but—without putting anything in writing—if he were to hand himself over to the Scottish army, they would protect his honour and conscience.

On 1 April, Montreuil wrote to Charles, and engagements were exchanged between them. The French Agent promised

Charles for his part promised to take no companions with him except his two nephews and John Ashburnham.

On 3 April, Montreuil left London for Southwell (a village near the camp of the Scottish army which, along with a contingent of the New Model Army, was besieging Newark-on-Trent), arriving at the King's Arms Inn (now the Saracen's Head). Montreuil was delegated by Charles to arrange terms. Montreuil took up lodgings in the large apartment (divided into a dining-room and bedroom) of the inn to the left of the gateway, while the Scots, possibly on the instigation of Edward Cludd, a leading Parliamentarian, made the palace their headquarters. The hostelry is an ancient one, being mentioned in deeds as far back as 1396. The French Agent is described by Clarendon as a young gentleman of parts very equal to the trust reposed in him, and not inclined to be made use of in ordinary dissimulation and cozenage. On visiting the Commissioners, he found them apparently pleased that the King desired to come to them, and accordingly drew up a document, of which he said they approved, assuring the King of full protection and assistance. Arrangements were to be made for the Scottish horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

to receive Charles at Harborough, but not feeling sure of the compact being kept, Charles asked Dr. Michael Hudson (a chaplain and during the war a military scout) to go in his stead.

Hudson went to Harborough, and finding no troops there, proceeded to Southwell, where Montreuil told him that the Scots were fearful of creating jealousy with Parliament. In no hopeful mood, and with no tidings except that Scots had promised to send a party of horse to Burton-on-Trent

Burton upon Trent, also known as Burton-on-Trent or simply Burton, is a market town in the borough of East Staffordshire in the county of Staffordshire, England, close to the border with Derbyshire. In 2011, it had a population of 72,299. Th ...

, Hudson returned to Oxford, where further letters from Montreuil were anxiously awaited. In one of these, dated Southwell, 10 April, these words occur:

Charles, however, felt he had no alternative. Ashburnham, who was in constant attendance upon him, said in a letter that the king felt he could not refrain from trying to reach the Scots, "first on account of his low condition in point of force, and the strong necessity he is brought into, not being able to supply his table. Secondly, because of the little hope he had of succour, and the certainty of being blocked up". Charles explained the motives by which he was animated in a letter to the Marquis of Ormond, in which he stated that having sent many gracious messages to Parliament without effect, and having received very good security that he and his friends would be safe with the Scots, who would assist with their forces in procuring peace, he had resolved to put himself to the hazard of passing into the Scots army now before Newark. This letter is dated Oxford, 13 April 1646; on 25 April, a letter was received from Montreuil, stating that the disposition of the Scotch commanders was now all that could be desired. The King left secretly on 26 April, accompanied only by John Ashburnham and Michael Hudson, the latter being familiar with the country and able to conduct the little party by the safest route.

Journey

At midnight on 27 April, Charles came with theDuke of Richmond

Duke of Richmond is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created four times in British history. It has been held by members of the royal Tudor and Stuart families.

The current dukedom of Richmond was created in 1675 for Charles ...

to Ashburnham's apartment. Scissors were used to cut the King's tresses and lovelock, and the peak of his beard was clipped off, so that he no longer looked like the man familiar to any who have seen his portraits by Anthony van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (, many variant spellings; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Brabantian Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh ...

.

Hudson had persuaded the King that it was not possible to travel directly from Oxford to the Scottish camp outside Newark-on-Trent

Newark-on-Trent or Newark () is a market town and civil parish in the Newark and Sherwood district in Nottinghamshire, England. It is on the River Trent, and was historically a major inland port. The A1 road bypasses the town on the line ...

, and that it would be better to go by a circuitous route, first towards London, then north-east, before turning north-west towards Newark. As a cover for part of the journey, Hudson had an old pass for a captain who was ostensibly to go to London to discuss his composition

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

*Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include v ...

with Parliament. Dressed in a scarlet cloak, Hudson represented the military bearer.;

At 2:00 am, Hudson went to the governor of Oxford, Sir Thomas Glemham

Sir Thomas Glemham (c. 1594 – 1649) was an English soldier, landowner and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1621 and 1625. He was a commander in the Royalist army during the English Civil War.

Early life and career

Glemham was ...

, who brought the keys to the gates. The clock struck three as they crossed the Magdalen Bridge

Magdalen Bridge spans the divided stream of the River Cherwell just to the east of the City of Oxford, England, and next to Magdalen College, whence it gets its name and pronunciation. It connects the High Street to the west with The Plain, n ...

. As they approached the start of the London-road, the Governor took his leave with a "Farewell, Harry"—for to that name Charles was now to answer. He was riding disguised as Ashburnham's servant, wearing a montero cap and carrying a cloak bag.

Charles was still hoping to hear from parties in London who would be willing to treat with him, but nothing was heard from that direction. Arriving at Hillingdon

Hillingdon is an area of Uxbridge within the London Borough of Hillingdon, centred 14.2 miles (22.8 km) west of Charing Cross. It was an ancient parish in Middlesex that included the market town of Uxbridge. During the 1920s the civ ...

, at that time a village near Uxbridge

Uxbridge () is a suburban town in west London and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Situated west-northwest of Charing Cross, it is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the London Plan. Uxb ...

and now in Greater London, the party dallied at the inn for several hours, debating on their future course. Three options were considered. The first was to continue to London, which was ruled out because there had been no word from there. The second option was to head north to the Scots, and a third option was to head for a port and seek a ship for the continent. They chose to head towards Kings Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is located north of London, north-east of Peterborough, nor ...

in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, which if it proved difficult to reach, or if no ships were available, left the Scottish option still open.

They proceeded on their way amidst risks and dangers. They passed through fourteen garrisons of the enemy, and in trying to avoid detection, the party had many narrow escapes.

On 30 April, Charles and Ashburnham decided to halt at Downham Market

Downham Market, sometimes simply referred to as Downham, is a market town and civil parish in Norfolk, England. It lies on the edge of the Fens, on the River Great Ouse, approximately 11 miles south of King's Lynn, 39 miles west of Norwich and 30 ...

, in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, while Hudson went on to Southwell to finalise the arrangements. In his statement to Parliament, Hudson said: "The business was concluded, and I returned with the consent of the Scotch Commissioners to the King, whom I found at the sign of the White Swan at Downham. I related all to his Majesty, and he resolved the next morning to go to them". Hudson later related the contents (when examined by the English Parliament) of the paper he carried (written by Montreuil, in French, because the Scots would not write down their terms):

Gardiner makes several points about this Scottish offer. The first is that the Scots were keen to gain physical possession of Charles, so their wording was on the edge of what they were willing to agree to. However, it is unlikely that the Scots realised just how strongly Charles disliked Presbyterianism (because of his belief that from "no bishops" it was but a small step to "no king"), and that although on 23 March he had promised that would agree to a Presbyterian church, he could always fall back on "contrary to his conscience" when later pressed on this issue. The second point was that not having put their terms in writing, the phrase in the fourth term "upon sending a message", if indeed that is what Montreuil's French original contained, is open to misinterpretation, as the King could send any message, no matter how indirect (Gardiner gives an example of "It had been raining in Oxford") and then demand Scottish armed support. It is more likely that the Scots meant "the message" containing the terms they had previously discussed with the King about Presbyterian becoming the official church in both kingdoms.

Before setting out again, as the King's disguise was by then known, it was thought necessary he should change it. So Charles changed into a clergyman's attire, and being called "Doctor", was to pass for Hudson's tutor.

The small party arrived at Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

on the evening of 3 May and stayed with Alderman Richard Wolph. Charles and his two companions left there between 10:00 pm and midnight on 4 May. Travelling all night, they went towards Allington and crossed the Trent at Gotham. quotes Dr Stukelet's account.

Early on 5 May 1646, Charles reached the King's Arms Inn in Southwell, where Montreuil was still residing. Charles stayed there during the morning, leaving after lunch. His arrival caused a stir, and among those who visited him was the Earl of Lothian. Lothian expressed surprise at "conditions" that Charles thought he had obtained before his arrival and denied them, adding that they could not be responsible for what their Commissioners in London might have agreed to. Lothian presented a series of demands to Charles: the surrender of Newark, that he sign the Covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

and order the establishment of Presbyterianism in England and Ireland, and to direct the commander of the Royalist Scottish field army, James Graham, Marquess of Montrose

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman, poet and soldier, lord lieutenant and later viceroy and captain general of Scotland. Montrose initially joined the Covenanters in the Wars of the Three K ...

, to lay down his arms. Charles refused all three requests and replied "He that made you an earl, made James Graham a marquess".;

Among others who arrived at the inn were two of the Scottish Commissioners, who stayed and dined with the King. After lunch, the King went via Upton across Kelham bridge to the headquarters of General David Leslie.

General David Leslie was in command of the Scottish army besieging Newark because Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland bec ...

, had left for Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

. When Charles presented himself before General Leslie (his headquarters were located in a large fortified camp which had been given the name Edinburgh), the Scottish general professed the greatest astonishment, because as Disraeli explained:

Whether this was or was not true, the Scots persisted in affirming that the arrival of Charles at their headquarters was wholly unexpected. The first letter on the subject was to the English Commissioners at Newark, in which they said they felt it their duty to acquaint them that the King had come into their army that morning, which they said "has overtaken us unexpectedly, filled us with amazement, and made us like men that dream". Their next letter on the subject was to the Committee of Both Kingdoms in London, and in it they affirmed that

W. D. Hamilton was of the opinion that the King's reply at Southwell to Lord Lothian settled the matter of his status: "He was no longer regarded as the guest of M. Montreuil, but as their prisoner"; and when the interview with David Leslie came to an end, the King was escorted to Kelham House, where he was to reside while staying with the Scottish army at Newark.

Immediate aftermath

At Kelham House, Charles was closely watched by a guard dignified by the name of "a guard of honour" while communications were passing with Parliament and negotiations were proceeding between the English and Scottish Commissioners, who met for the purpose in the fields between Kelham and Farndon, an area called Faringdon. Montreuil, Ashburnham, and Hudson were still there, and from Ashburnham's narrative, it seems that Charles felt it wise to try the effect of a little negotiation on his own account. Ashburnham says "the King, recognising his difficulty, turned his thoughts another way, and resolved to come to the English if terms could be arranged".

Ashburnham took steps to effect this, nominating as negotiators Lord Belasyse, governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont (MP), and requested that they communicate with him, but Lord Belasyse told him, when they conversed together after the surrender of Newark, that Pierrepont "would by no means admit any discourse with me in the condition I then stood, the action of waiting on the King to the Scots army rendering me more obnoxious to the Parliament than any man living, and so those thoughts of his Majesty going to the English vanished".

If Ashburnham had succeeded in his negotiations at Kelham, the whole course of events would have been changed. As it was, the Scots held their prize securely. In the records of the House of Lords, there is a document signed by eight noblemen who had heard of the jealous way in which the King was watched, protesting against "strict guard being kept by the Scots army about the house where the King then was", and none being suffered to have access to his person without their permission.

At Kelham House, Charles was closely watched by a guard dignified by the name of "a guard of honour" while communications were passing with Parliament and negotiations were proceeding between the English and Scottish Commissioners, who met for the purpose in the fields between Kelham and Farndon, an area called Faringdon. Montreuil, Ashburnham, and Hudson were still there, and from Ashburnham's narrative, it seems that Charles felt it wise to try the effect of a little negotiation on his own account. Ashburnham says "the King, recognising his difficulty, turned his thoughts another way, and resolved to come to the English if terms could be arranged".

Ashburnham took steps to effect this, nominating as negotiators Lord Belasyse, governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont (MP), and requested that they communicate with him, but Lord Belasyse told him, when they conversed together after the surrender of Newark, that Pierrepont "would by no means admit any discourse with me in the condition I then stood, the action of waiting on the King to the Scots army rendering me more obnoxious to the Parliament than any man living, and so those thoughts of his Majesty going to the English vanished".

If Ashburnham had succeeded in his negotiations at Kelham, the whole course of events would have been changed. As it was, the Scots held their prize securely. In the records of the House of Lords, there is a document signed by eight noblemen who had heard of the jealous way in which the King was watched, protesting against "strict guard being kept by the Scots army about the house where the King then was", and none being suffered to have access to his person without their permission.

See also

* Escape of Charles II (3 September – 16 October 1651) after the Royalist defeat at theBattle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell d ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * Attribution: *Further reading

* * *{{cite ODNB, mode=cs2, ref=none , last=Cranfield , first=Nicholas W. S. , year=2004 , title=Hudson, Michael (1605–1648) , id=14037 First English Civil War Charles I of England