Charles Francis Adams Sr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Francis Adams Sr. (August 18, 1807 – November 21, 1886) was an American historical editor, writer, politician, and diplomat. As

In 1840, Adams was elected to three one-year terms in the

In 1840, Adams was elected to three one-year terms in the

On September 3, 1829, he married Abigail Brown Brooks (1808–1889), whose father was shipping magnate Peter Chardon Brooks (1767–1849). She had two sisters, Charlotte, who was married to

On September 3, 1829, he married Abigail Brown Brooks (1808–1889), whose father was shipping magnate Peter Chardon Brooks (1767–1849). She had two sisters, Charlotte, who was married to

"Abigail Brooks Adams"

''womenhistoryblog.com'', August 18, 2015. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

''Diary of Charles Francis Adams''

(2 vols.). Harvard University Press, 1964. *

Appleton's Biography edited by Stanley L. Klos

* * * Charles Francis Adams, Sr

Civil War era diaries Digital Edition

Nagel, Paul. ''Descent from Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

''Texas and the Massachusetts Resolutions''

by Charles Francis Adams, published 1844, hosted by th

Portal to Texas History

Selected diplomatic Letters of the Lincoln administration

at Ford's Theatre site, including several to or from Adams

Mount Wollaston Cemetery Tour

(includes grave image) , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, Charles Francis Sr. 1807 births 1886 deaths People from Beacon Hill, Boston Politicians from Boston Lawyers from Boston Adams, Charles Francis I Thomas Johnson family American people of English descent Massachusetts Whigs Massachusetts Free Soilers Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts 1848 United States vice-presidential candidates 1872 United States vice-presidential candidates Massachusetts state senators Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Massachusetts lawyers Politicians from Quincy, Massachusetts Children of presidents of the United States 19th-century American diplomats Harvard College alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War

United States Minister to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarch ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Adams was crucial to Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

efforts to prevent British recognition of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

and maintain European neutrality to the utmost extent. Adams also featured in national and state politics before and after the Civil War.

Adams was the patriarch of one of the United States's most prominent political families: his father and grandfather were Presidents John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

, about whom he wrote a major biography. He had seven children, including John Quincy II, Charles Jr., Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

, and Brooks

Brooks may refer to:

Places

;Antarctica

*Cape Brooks

;Canada

*Brooks, Alberta

;United States

* Brooks, Alabama

* Brooks, Arkansas

*Brooks, California

*Brooks, Georgia

* Brooks, Iowa

* Brooks, Kentucky

* Brooks, Maine

* Brooks Township, Michigan ...

.

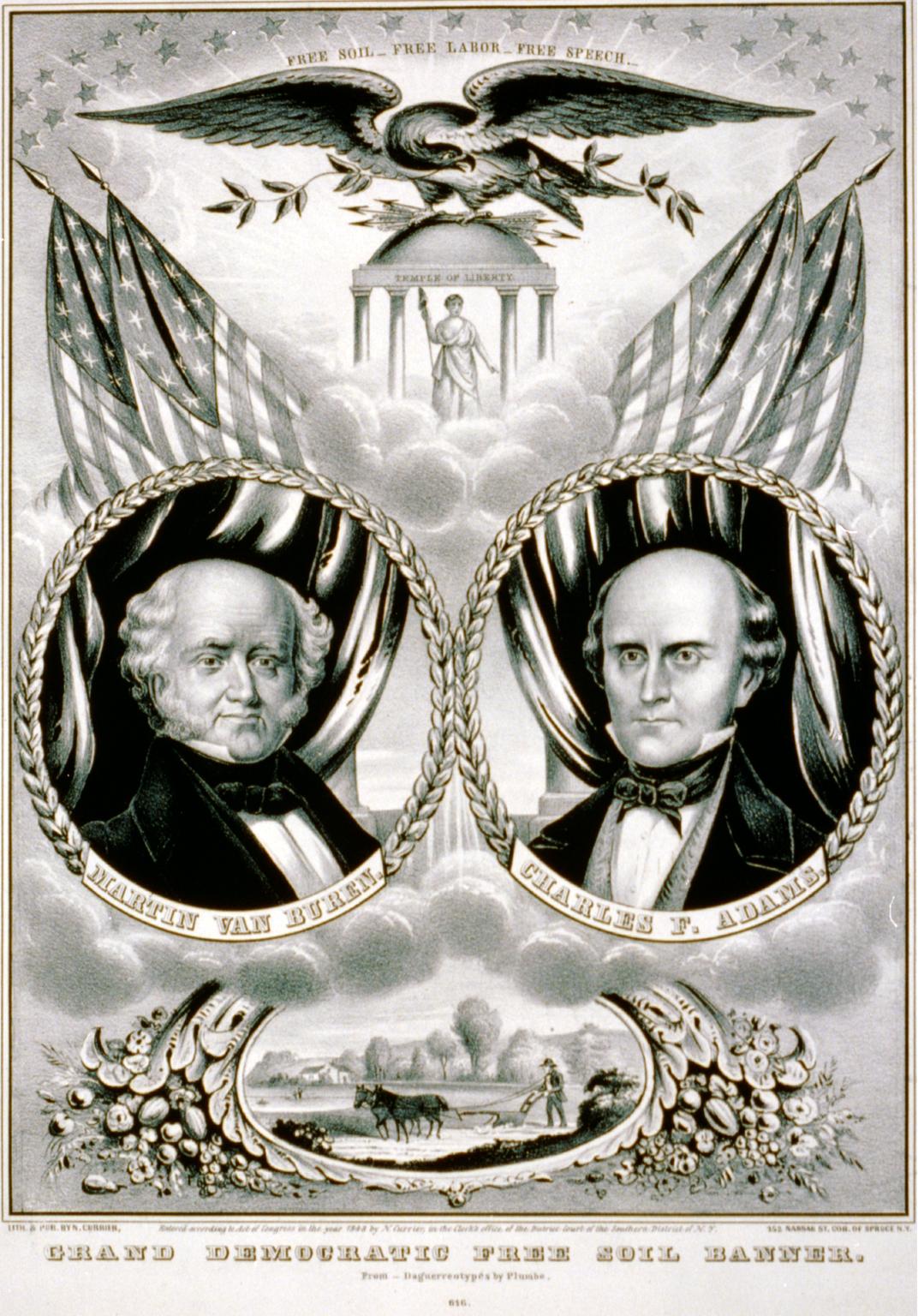

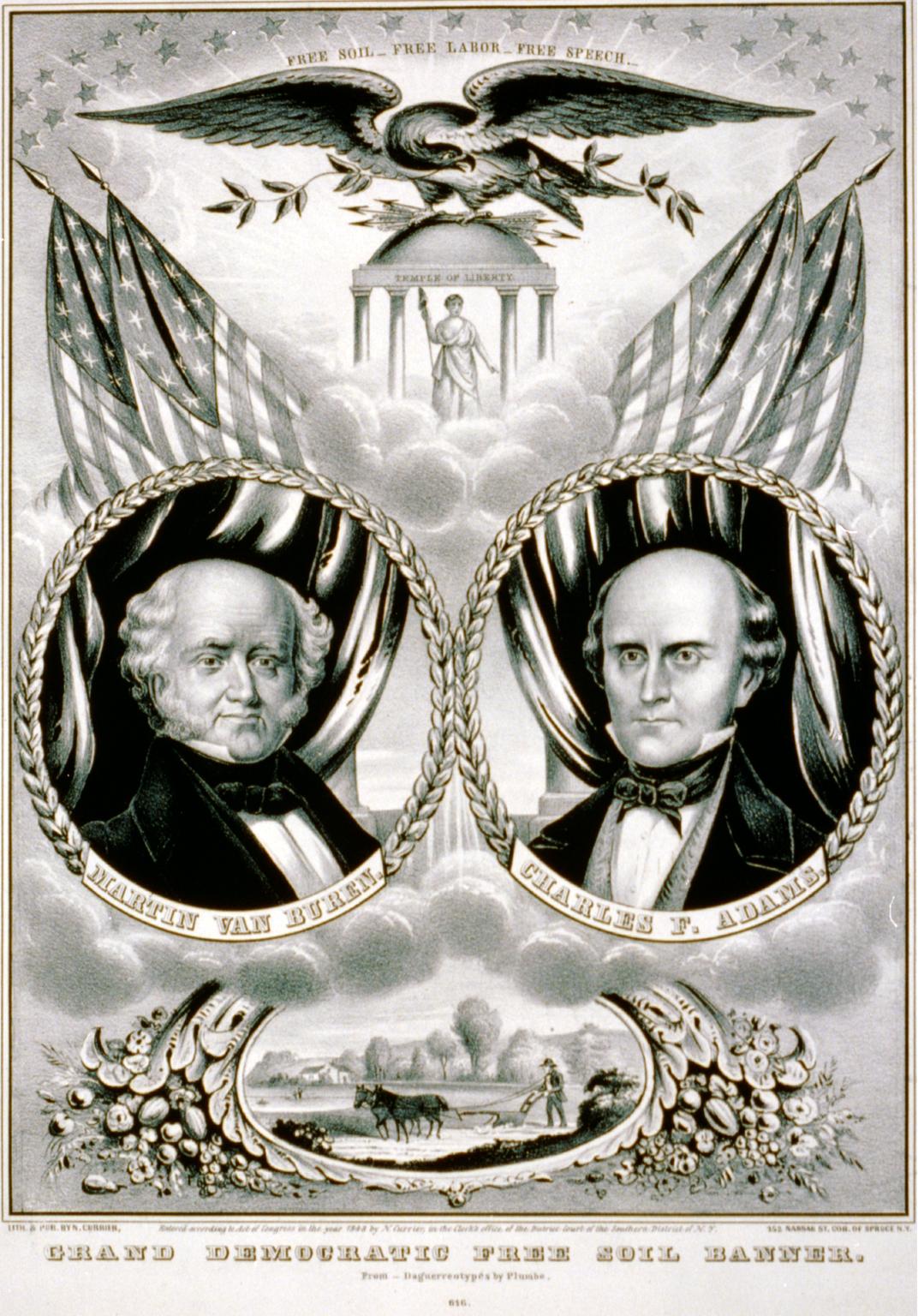

Adams served two terms in the Massachusetts State Senate

The Massachusetts Senate is the upper house of the Massachusetts General Court, the bicameral state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Senate comprises 40 elected members from 40 single-member senatorial districts in the st ...

before helping to found the abolitionist Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

in 1848; he was the party's vice-presidential candidate in the election of 1848 on a ticket with former president Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

in 1858 and re-elected in 1860.

During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Adams served as the United States Minister to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarch ...

under Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, where he played a key role in keeping the British government neutral and not diplomatically recognizing the Confederacy. After the War, he became alienated from the Republican Party and was successively a Liberal Republican, Anti-Mason, and Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

. In 1876, he was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the chief executive officer of the government of Massachusetts. The governor is the head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

Massachuset ...

.

Adams became an overseer of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

and built the Stone Library at Peacefield

Peacefield, also called Peace field or Old House, is a historic home formerly owned by the Adams family of Quincy, Massachusetts. It was the home of United States Founding Father and U.S. president John Adams and First Lady Abigail Adams, and o ...

, the Adams' family home which is now part of the Adams National Historical Park

Adams National Historical Park, formerly Adams National Historic Site, in Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolit ...

in Quincy, Massachusetts, to honor his father.

Early life

Adams was born inBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

on August 18, 1807, and he was one of three sons and a daughter born to John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

(1767–1848) and Louisa Catherine Johnson

Louisa Catherine Adams (Married and maiden names, ''née'' Johnson; February 12, 1775 – May 15, 1852) was the First Lady of the United States from 1825 to 1829 during the presidency of John Quincy Adams.

Early life

Adams was born on Februar ...

(1775–1852). His older brothers were George Washington Adams (1801–1829) and John Adams II

John Adams II (July 4, 1803 – October 23, 1834) was an American government functionary and businessman. The second son of President John Quincy Adams and Louisa Adams, he is usually called John Adams II to distinguish him from President John Ad ...

(1803–1834). His sister, Louisa, was born in 1811 but died in 1812 while the family was in Russia. He was named in part after Francis Dana

Francis Dana (June 13, 1743 – April 25, 1811) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, jurist, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1777–1778 and 1784. A signer of the Articles of Confederati ...

.

He attended Boston Latin School and Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, where he graduated in 1825. He then studied law with Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

, attained admission to the bar, and practiced in Boston. He wrote numerous reviews of works about American and British history for the ''North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived at ...

''.

During the presidency of John Quincy Adams (1825–1829), Charles and his brothers John and George were all rivals for the same woman, their cousin Mary Catherine Hellen, who lived with the Adams family after the death of her parents. In 1828, John married Mary in a White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

ceremony, and both Charles and George declined to attend.

Career

In 1840, Adams was elected to three one-year terms in the

In 1840, Adams was elected to three one-year terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

and he served in the Massachusetts Senate

The Massachusetts Senate is the upper house of the Massachusetts General Court, the bicameral state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Senate comprises 40 elected members from 40 single-member senatorial districts in the st ...

from 1843 to 1845. In 1846, he purchased and became editor of the ''Boston Whig'' newspaper. In 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

, he was the unsuccessful nominee of the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

for Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, running on a ticket with former president Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

as the presidential nominee.

From the 1840s, Adams became one of the finest historical editors of his era. He developed his expertise in part because of the example of his father, who in 1829 had turned from politics (after his defeated bid for a second presidential term in 1828) to history and biography. John Quincy Adams began a biography of his father, John Adams, but wrote only a few chapters before resuming his political career in 1830 with his election to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The younger Adams, fresh from his edition of the letters of his grandmother Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams ( ''née'' Smith; November 22, [ O.S. November 11] 1744 – October 28, 1818) was the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, as well as the mother of John Quincy Adams. She was a founder of the United States, an ...

, '' Letters of Mrs. Adams, the Wife of John Adams'' (1840), took up the project that his father had left uncompleted and between 1850 and 1856, turned out not just the two volumes of the biography but eight further volumes presenting editions of John Adams's ''Diary and Autobiography'', his major political writings, and a selection of letters and speeches. The edition, titled ''The Works of John Adams, Esq., Second President of the United States'', was the only edition of John Adams's writings until the family donated the cache of Adams papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1854 and authorized the creation of the Adams Papers project; the modern project had published accurate scholarly editions of John Adams's diary and autobiography, several volumes of Adams family correspondence, two volumes on the portraits of John and Abigail Adams and John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams, and the early years of the diary of Charles Francis Adams, who published a revised edition of the biography in 1871. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1857.

Congressman and diplomat

As aRepublican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, Adams was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

in 1858, where he chaired the Committee on Manufactures. He was re-elected in 1860, but resigned to become U.S. minister (ambassador) to the Court of St James's (Britain), a post previously held by his father and grandfather, from 1861 to 1868. Powerful Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

had wanted the position and so became alienated from Adams. Britain had already recognized Confederate belligerency, but Adams was instrumental in maintaining British neutrality and preventing British diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

Part of his duties included corresponding with British civilians, including Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

. Adams and his son, Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fr ...

, who served as his private secretary, also were kept busy monitoring Confederate diplomatic intrigues and the construction of rebel commerce raiders

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than eng ...

by British shipyards (like ''hull N°290'', launched as ''Enrica'' from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

but was soon transformed near the Azores Islands

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

into sloop-of-war CSS ''Alabama'').

His main success as a diplomat was in keeping Britain neutral. He helped resolve the Trent Affair

The ''Trent'' Affair was a diplomatic incident in 1861 during the American Civil War that threatened a war between the United States and Great Britain. The U.S. Navy captured two Confederate envoys from a British Royal Mail steamer; the Brit ...

in 1861, in which an American naval officer had violated British rights. With the Union blockade of Confederate ports growing increasingly successful, little cotton now reached Europe except through Union channels. A strong element in Britain, including Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone, wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy. Adams warned doing so would mean war with the United States, as well as the cutting off American food exports, which constituted about a fourth of the British food supply. The American Navy, increasingly strong, would try to sink British shipping.

The British government pulled back from talk of war when the Confederate invasion of the North was defeated at Antietam, and Lincoln announced that he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Adams and his staff collected details on the shipbuilding issue, showing how warships built for the Confederacy caused widespread damage to the American merchant marine. The evidence became the basis of the postwar Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the federal government of the United States, government of the United States from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon ...

. The claims went to arbitration, with Adams in charge of the American side. The British in 1872 agreed to pay $15 million in damages.

Meeting with Joseph Smith

In 1844, while traveling with his cousin Josiah Quincy, Charles Francis Adams metJoseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, ...

, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ and the Latter Day Saints, in Nauvoo, Illinois, and received a copy of the Book of Mormon which had previously belonged to Smith's first wife, Emma Smith

Emma Hale Smith Bidamon (July 10, 1804 – April 30, 1879) was an American homesteader, the official wife of Joseph Smith, and a prominent leader in the early days of the Latter Day Saint movement, both during Smith's lifetime and afterward as ...

. The book is now in the archive collections of Adams National Historical Park

Adams National Historical Park, formerly Adams National Historic Site, in Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolit ...

. At the visit, Smith showed Adams and Quincy four Egyptian mummies and ancient papyri. Adams was not impressed by Smith, and wrote in his diary entry that day, "Such a man is a study not for himself, but as serving to show what turns the human mind will sometimes take. And herafter if I should live, I may compare the results of this delusion with the condition in which I saw it and its mountebank apostle."

Later life

Back in Boston, Adams declined the presidency of Harvard University, but became one of its overseers in 1869. In 1870 he built the first presidential library in the United States to honor his father John Quincy Adams. The Stone Library includes over 14,000 books written in twelve languages. The library is atPeacefield

Peacefield, also called Peace field or Old House, is a historic home formerly owned by the Adams family of Quincy, Massachusetts. It was the home of United States Founding Father and U.S. president John Adams and First Lady Abigail Adams, and o ...

(also known as the "Old House") which is now part of Adams National Historical Park

Adams National Historical Park, formerly Adams National Historic Site, in Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolit ...

in Quincy, Massachusetts.

In 1876, Adams ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts.

During the 1876 electoral college controversy, Adams sided with Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Samuel J. Tilden over Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

for the White House.

Personal life

On September 3, 1829, he married Abigail Brown Brooks (1808–1889), whose father was shipping magnate Peter Chardon Brooks (1767–1849). She had two sisters, Charlotte, who was married to

On September 3, 1829, he married Abigail Brown Brooks (1808–1889), whose father was shipping magnate Peter Chardon Brooks (1767–1849). She had two sisters, Charlotte, who was married to Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

, a Massachusetts politician, and Ann, who was married to Nathaniel Frothingham, a Unitarian minister. Together, they were the parents of:

* Louisa Catherine Adams (1831–1870), who married Charles Kuhn

* John Quincy Adams II

John Quincy Adams II (September 22, 1833 – August 14, 1894) was an American politician who represented Quincy in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1866 to 1867, 1868 to 1869, 1871 to 1872, and from 1874 to 1875.

Adams served as ...

(1833–1894)

* Charles Francis Adams Jr.

Charles Francis Adams Jr. (May 27, 1835 – March 20, 1915) was an American author, historian, and railroad and park commissioner who served as the president of the Union Pacific Railroad from 1884 to 1890. He served as a colonel in the Union Arm ...

(1835–1915)

* Henry Brooks Adams (1838–1918)

* Arthur George Adams (1841–1846), who died young

* Mary Gardiner Adams (1845–1928), who married Dr. Henry Parker Quincy

* Peter Chardon Brooks Adams (1848–1927)

Adams died in Boston on November 21, 1886, and was interred in Mount Wollaston Cemetery

Mount Wollaston Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery at 20 Sea Street in the Merrymount neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts. It was founded in 1855 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

History

In 1854 when Hancock ...

, Quincy. He was the last surviving child of John Quincy Adams.

His wife Abigail's "health and spirits" worsened after her husband's death, and she died at Peacefield

Peacefield, also called Peace field or Old House, is a historic home formerly owned by the Adams family of Quincy, Massachusetts. It was the home of United States Founding Father and U.S. president John Adams and First Lady Abigail Adams, and o ...

on June 6, 1889.MacLean, Maggie"Abigail Brooks Adams"

''womenhistoryblog.com'', August 18, 2015. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

References

Notes Sources * Adams, Jr., Charles Francis, ''Charles Francis Adams'', Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900. * Butterfield, L. H. et al., eds., ''The Adams Papers'' (1961– ). Multivolume letterpress edition of all letters to and from major members of the Adams family, plus their diaries; still incomplete. * Donald, Aida Dipace and Donald, David Herbert, eds.''Diary of Charles Francis Adams''

(2 vols.). Harvard University Press, 1964. *

Duberman, Martin

Martin Bauml Duberman (born August 6, 1930) is an American historian, biographer, playwright, and gay rights activist. Duberman is Professor of History Emeritus at Herbert Lehman College in the Bronx, New York City.

Early life

Duberman was born ...

. ''Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1886''. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1961, reissued by Stanford University Press, 1968.

* Egerton, Douglas R. ''Heirs of an Honored Name: The Decline of the Adams Family and the Rise of Modern America''. Basic Books, 2019.

*

*

*

External links

*Appleton's Biography edited by Stanley L. Klos

* * * Charles Francis Adams, Sr

Civil War era diaries Digital Edition

Nagel, Paul. ''Descent from Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

''Texas and the Massachusetts Resolutions''

by Charles Francis Adams, published 1844, hosted by th

Portal to Texas History

Selected diplomatic Letters of the Lincoln administration

at Ford's Theatre site, including several to or from Adams

Mount Wollaston Cemetery Tour

(includes grave image) , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, Charles Francis Sr. 1807 births 1886 deaths People from Beacon Hill, Boston Politicians from Boston Lawyers from Boston Adams, Charles Francis I Thomas Johnson family American people of English descent Massachusetts Whigs Massachusetts Free Soilers Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts 1848 United States vice-presidential candidates 1872 United States vice-presidential candidates Massachusetts state senators Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Massachusetts lawyers Politicians from Quincy, Massachusetts Children of presidents of the United States 19th-century American diplomats Harvard College alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War