Charles Dawson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Dawson (11 July 1864 – 10 August 1916) was a British amateur

He analyzed ancient quarries, re-examined the Bayeux Tapestry, and produced the first conclusive study of Hastings Castle. He later found fake evidence for the final phases of Roman occupation in Britain at

He analyzed ancient quarries, re-examined the Bayeux Tapestry, and produced the first conclusive study of Hastings Castle. He later found fake evidence for the final phases of Roman occupation in Britain at

Dawson claimed to have discovered a collection of fossils that have been dug up in Piltdown, Sussex, including an ape-like jawbone and a human-like skull. However, after his death, it was proven that the remains were evidently forged. For years, the creator of these remains was unknown, though it was then determined, through a meticulous inspection of his finds and collections, that Charles Dawson was most likely responsible for this forgery.

Dawson claimed to have discovered a collection of fossils that have been dug up in Piltdown, Sussex, including an ape-like jawbone and a human-like skull. However, after his death, it was proven that the remains were evidently forged. For years, the creator of these remains was unknown, though it was then determined, through a meticulous inspection of his finds and collections, that Charles Dawson was most likely responsible for this forgery.

Project Piltdown

at

Archive of Piltdown-related papers

at Clark University

Annotated bibliography of Piltdown Man materials

by T. H. Turrittin – See especially section 15 related to Charles Dawson

Reevaluation of a supposedly Roman iron figure

found by Charles Dawson, but later determined not to be Roman *

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-37021144 "Piltdown review points decisive finger at forger Dawson" BBC News {{DEFAULTSORT:Dawson, Charles 1864 births 1916 deaths Amateur archaeologists Deaths from sepsis Pseudoarchaeologists Archaeological forgery Forgers Hoaxers Writers from Preston, Lancashire

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

who claimed to have made a number of archaeological and palaeontological discoveries that were later exposed as fraud

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compen ...

s. These forgeries included the Piltdown Man

The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from the beginning, the remains ...

(''Eoanthropus dawsoni''), a unique set of bones that he found in 1912 in Sussex. Many technological methods such as fluorine testing indicate that this discovery was a hoax and Dawson, the only one with the skill and knowledge to generate this forgery, was a major suspect.

The eldest of three sons, Dawson moved with his family from Preston, Lancashire

Preston () is a city on the north bank of the River Ribble in Lancashire, England. The city is the administrative centre of the county of Lancashire and the wider City of Preston local government district. Preston and its surrounding distr ...

, to Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

, when he was still very young. Charles initially studied as a lawyer following his father and then pursued a hobby of collecting and studying fossils.

He made a number of seemingly important fossil finds. Amongst these were teeth from a previously unknown species of mammal, later named ''Plagiaulax

''Plagiaulax'' is a genus of mammal from the Lower Cretaceous of Europe. It was a member of the also extinct order Multituberculata, and shared the world with dinosaurs. It is of the suborder "Plagiaulacida" and family Plagiaulacidae. The genus ...

dawsoni'' in his honour; three new species of dinosaur, one later named '' Iguanodon dawsoni''; and a new form of fossil plant, '' Salaginella dawsoni''. The British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

awarded him the title of 'Honorary Collector.' He was then elected fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

for his discoveries and a few years later, he joined the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

. Dawson died prematurely from pernicious anaemia

Pernicious anemia is a type of vitamin B12 deficiency anemia, a disease in which not enough red blood cells are produced due to the malabsorption of vitamin B12. Malabsorption in pernicious anemia results from the lack or loss of intrinsic ...

in 1916 at Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. It is the police and judicial centre for all of Sussex and is home to Sussex Police, East Sussex Fire & Rescue Service, Lewes Crown Court and HMP Lewes. The civil parish is the centre of t ...

, Sussex.

Alleged discoveries

In 1889, Dawson was a co-founder of theHastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

and St Leonards Museum Association, one of the first voluntary museum friends' groups organized in Britain. Dawson worked on a voluntary basis as a member of the Museum Committee, in charge of the acquisition of artifacts and historical documents. His interest in archaeology developed and he had an uncanny knack for making spectacular discoveries, leading ''The Sussex Daily News'' to name him the "Wizard of Sussex".Walsh (1996)

In 1893, Dawson investigated a curious flint mine full of prehistoric, Roman and medieval artifacts in the Lavant Caves, near Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ...

, and probed two tunnels beneath Hastings Castle

Hastings Castle is a keep and bailey castle ruin situated in the town of Hastings, East Sussex. It overlooks the English Channel, into which large parts of the castle have fallen over the years.

History

Immediately after landing in Englan ...

. In the same year, he presented the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

with a Roman statuette from Beauport Park

Beauport Park is a house near Hastings, East Sussex, England. It is located at the western end of the ridge of hills sheltering Hastings from the north and east.

Roman occupation

In 1862, the Rector of Hollington Church found a huge slag hea ...

that was made, uniquely for the period, of cast iron. Other discoveries followed, including a strange form of hafted Neolithic stone axe and a well-preserved ancient timber boat.

He analyzed ancient quarries, re-examined the Bayeux Tapestry, and produced the first conclusive study of Hastings Castle. He later found fake evidence for the final phases of Roman occupation in Britain at

He analyzed ancient quarries, re-examined the Bayeux Tapestry, and produced the first conclusive study of Hastings Castle. He later found fake evidence for the final phases of Roman occupation in Britain at Pevensey Castle

Pevensey Castle is a medieval castle and former Roman Saxon Shore fort at Pevensey in the English county of East Sussex. The site is a scheduled monument in the care of English Heritage and is open to visitors. Built around 290 AD and known to ...

in Sussex. Investigating unusual elements of the natural world, Dawson presented a petrified toad inside a flint nodule, discovered a large supply of natural gas at Heathfield in East Sussex, reported on a sea-serpent in the English Channel, observed a new species of human, and found a strange goldfish/carp hybrid. It was even reported that he was experimenting with phosphorescent bullets as a hindrance to Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

attacks on London during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

In appreciation for the donation of fossils Dawson provided to the British Museum, he was given the title of 'Honorary Collector' and in 1885, he was elected a fellow of the Geological Society as a result of his numerous discoveries. He was then elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

in 1895. He was now Charles Dawson F.G.S., F.S.A at the age of 31, without a university degree to his name. Dawson died without receiving a knighthood.

His most famous 'find' was the 1912 discovery of the Piltdown Man

The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from the beginning, the remains ...

which was billed as the " missing link" between humans and other great apes

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

. Following his death in 1916, no further 'discoveries' were made at Piltdown. Questions about the Piltdown find were raised from the beginning, first by Arthur Keith

Sir Arthur Keith FRS FRAI (5 February 1866 – 7 January 1955) was a British anatomist and anthropologist, and a proponent of scientific racism. He was a fellow and later the Hunterian Professor and conservator of the Hunterian Museum of the R ...

, but also by palaeontologists and anatomists from the United States and Europe. Defence of the fossils was led by Arthur Smith Woodward

Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, FRS (23 May 1864 – 2 September 1944) was an English palaeontologist, known as a world expert in fossil fish. He also described the Piltdown Man fossils, which were later determined to be fraudulent. He is not relate ...

at the Natural History Museum in London. The debate was rancorous at times and the response to those disputing the finds often became personally abusive. Challenges to Piltdown Man arose again in the 1920s, but were again dismissed.

Posthumous analysis

In 1949, further questions were raised about thePiltdown Man

The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from the beginning, the remains ...

and its authenticity, which led to the conclusive demonstration that Piltdown was a hoax in 1953. Since then, a number of Dawson's other finds have also been shown to be forged or planted.

In 2003, Miles Russell of Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University is a public university in Bournemouth, England, with its main campus situated in neighbouring Poole. The university was founded in 1992; however, the origins of its predecessor date back to the early 1900s.

The univer ...

published the results of his investigation into Dawson's antiquarian collection and concluded that at least 38 specimens were clear fakes. Russell has noted that Dawson's whole academic career appears to have been "one built upon deceit, sleight of hand, fraud and deception, the ultimate gain being international recognition." Among these were the teeth of a reptile/mammal hybrid, ''Plagiaulax dawsoni'', "found" in 1891 (and whose teeth had been filed down in the same way that the teeth of Piltdown Man were to be some 20 years later); the so-called "shadow figures" on the walls of Hastings Castle

Hastings Castle is a keep and bailey castle ruin situated in the town of Hastings, East Sussex. It overlooks the English Channel, into which large parts of the castle have fallen over the years.

History

Immediately after landing in Englan ...

; a unique hafted stone axe; the Bexhill boat (a hybrid seafaring vessel); the Pevensey

Pevensey ( ) is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The main village is located north-east of Eastbourne, one mile (1.6 km) inland from Pevensey Bay. The settlement of Pevensey Bay forms part ...

bricks (allegedly the latest datable "finds" from Roman Britain); the contents of the Lavant Caves (a fraudulent "flint mine"); the Beauport Park

Beauport Park is a house near Hastings, East Sussex, England. It is located at the western end of the ridge of hills sheltering Hastings from the north and east.

Roman occupation

In 1862, the Rector of Hollington Church found a huge slag hea ...

"Roman" statuette (a hybrid iron object); the Bulverhythe

Bulverhythe, also known as West St Leonards and Bo Peep, is a suburb of Hastings, East Sussex, England with its Esplanade and 15 ft thick sea wall. Bulverhythe is translated as "Burghers' landing place". It used to be under a small headland ...

Hammer (shaped with an iron knife in the same way as the Piltdown elephant bone implement would later be); a fraudulent "Chinese" bronze vase; the Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

"Toad in the Hole" (a toad entombed within a flint nodule); the English Channel sea serpent; the Uckfield

Uckfield () is a town in the Wealden District of East Sussex in South East England. The town is on the River Uck, one of the tributaries of the River Ouse, on the southern edge of the Weald.

Etymology

'Uckfield', first recorded in writing as ...

Horseshoe (another hybrid iron object) and the Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. It is the police and judicial centre for all of Sussex and is home to Sussex Police, East Sussex Fire & Rescue Service, Lewes Crown Court and HMP Lewes. The civil parish is the centre of t ...

Prick Spur. Of his antiquarian publications, most demonstrate evidence of plagiarism or at least naive referencing as Russell wrote: "Piltdown was not a 'one-off' hoax, more the culmination of a life's work."

Piltdown Man

Dawson claimed to have discovered a collection of fossils that have been dug up in Piltdown, Sussex, including an ape-like jawbone and a human-like skull. However, after his death, it was proven that the remains were evidently forged. For years, the creator of these remains was unknown, though it was then determined, through a meticulous inspection of his finds and collections, that Charles Dawson was most likely responsible for this forgery.

Dawson claimed to have discovered a collection of fossils that have been dug up in Piltdown, Sussex, including an ape-like jawbone and a human-like skull. However, after his death, it was proven that the remains were evidently forged. For years, the creator of these remains was unknown, though it was then determined, through a meticulous inspection of his finds and collections, that Charles Dawson was most likely responsible for this forgery.

Unmasking the hoax

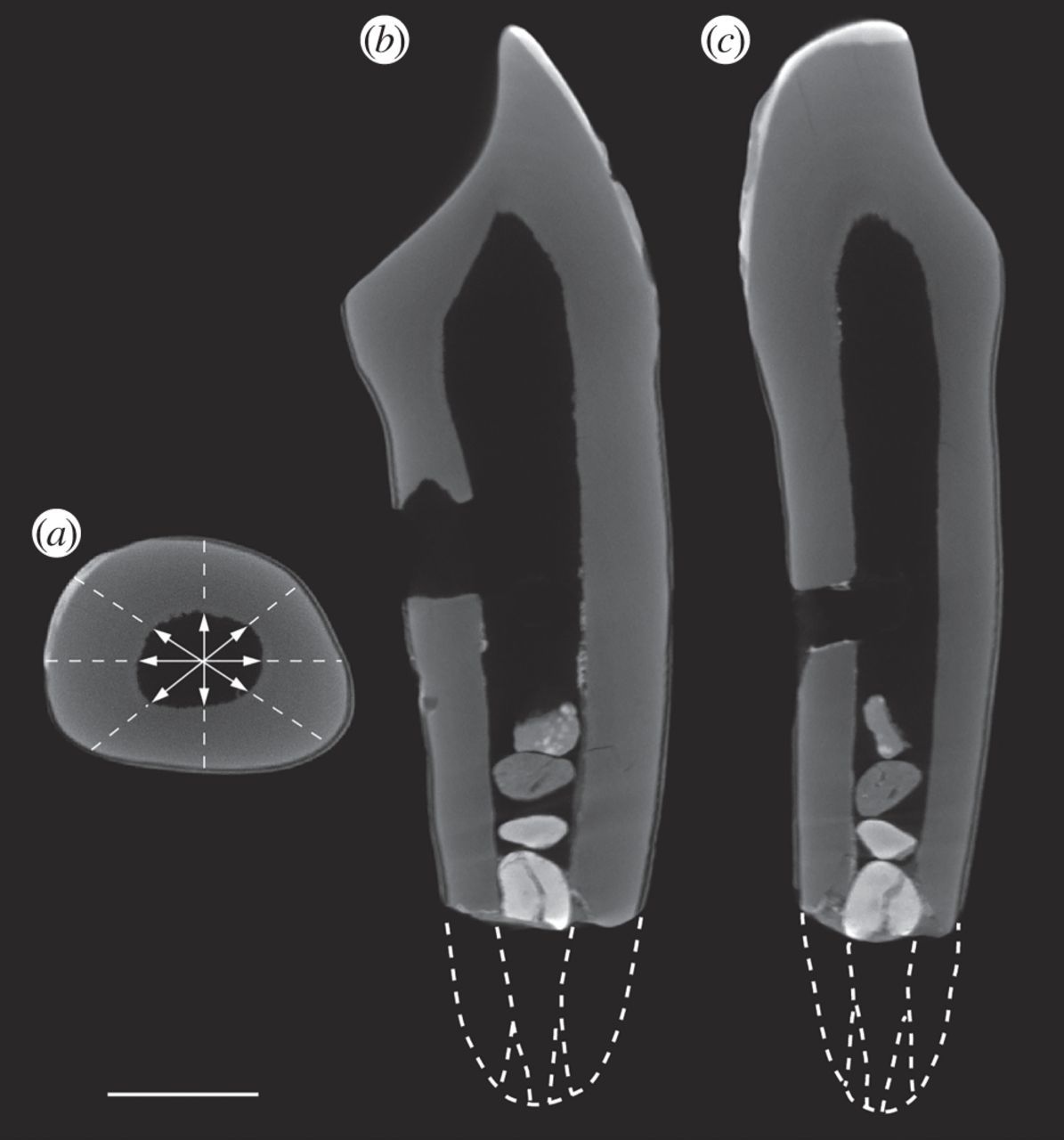

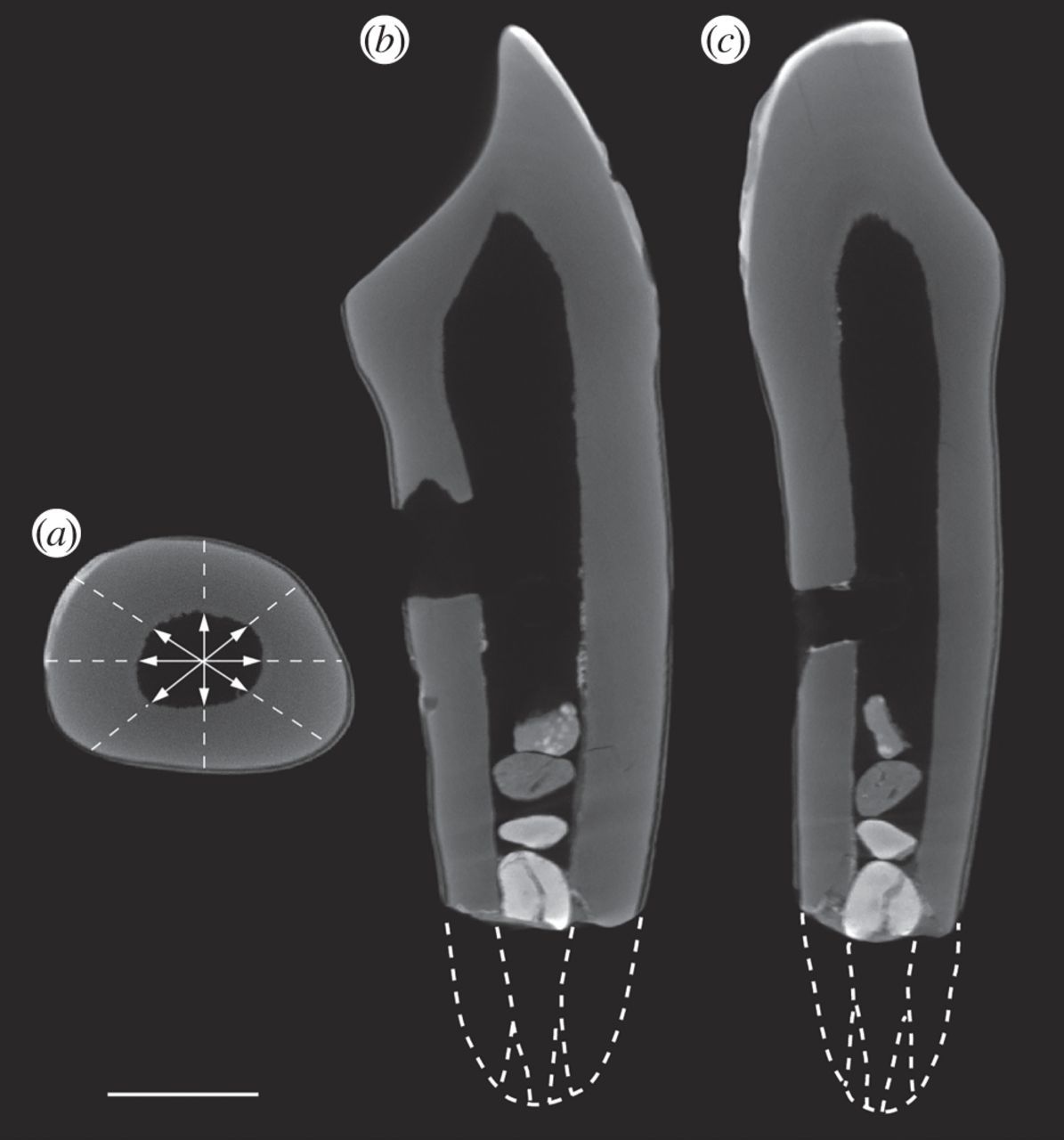

As more human fossils were discovered, it appeared that they had little similarities with the Piltdown Man. The Piltdown Man was then re-examined through new, rigorous technological methods which ultimately uncovered the hoax. Fluoride-based tests, chemical tests that date fossils by the amount of fluorine buried bones absorb from the soil, were used to date the Piltdown remains. This test, validated by a nitrogen-based test, dated the skull to not more than 50,000 years old, far more recent than Dawson proposed, and dated the jawbone to decades old. This meant that the Piltdown Man could not have been an ancestor of modern humans. Furthermore, chemical tests displayed that the fossils had been artificially stained by iron and chromium to appear medieval. Also, CT scans used to analyzed the inside of the bones indicated that many bones were loaded with gravel and were then sealed with putty. Even more so, X-rays indicate that the teeth have been flattened by filing or grinding to appear like human teeth. Lastly, in 2016, a team of British researchers used DNA studies to provide added evidence for the provenance of Piltdown Man. It was determined that the Piltdown I jawbone and the Piltdown II molar tooth came from a single orangutan and the cranial bones came from primitive humans. Despite the consistency of the findings, analyses of the material exhibit the forger was not trained professionally as the materials had fractured bones, putty that set too fast, and cracked teeth.

Revealing the forger

Most agree that the Piltdown Man was forged by a single individual, and that this was most probably Charles Dawson. Dawson was the suspected perpetrator in this hoax for many reasons. First, Dawson had previous history of deception: he was responsible for about 38 forgeries, plagiarized a historical account ofHastings Castle

Hastings Castle is a keep and bailey castle ruin situated in the town of Hastings, East Sussex. It overlooks the English Channel, into which large parts of the castle have fallen over the years.

History

Immediately after landing in Englan ...

, and had pretended to act on behalf of the Sussex Archeological Society. However, most people were unaware of this. Second, he was majorly involved in the Piltdown findings. He initiated the story of the Piltdown finds and was the one who contacted Woodward about them. He was the sole person to have seen the Piltdown II site and never disclosed the facts about this site; the fact that the techniques used to create both Piltdown I and Piltdown II were so similar suggests a single forger. Also, he was the only person present at every discovery; nothing was ever discovered at the site when he was not physically present and no other fossils were found after he died. Third, not only did he have access to the museum and antiquarian shops that carried these objects, he was also a popular collector, an amazing networker, and knew what the British scientific community expected in a missing link between apes and humans.

It has been suggested that Dawson's motive for this forgery had been his strong desire for scientific recognition and to join the archeological Royal Society. Between 1883 and 1909, Dawson wrote 50 publications though none were important enough to elevate his career. In 1909, he wrote a letter to Smith Woodward, with an unhappy heart, saying that he wanted to uncover a significant discovery though he never seems to come across one. Just six weeks later, Dawson's wife wrote a letter to the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

, pleading on behalf of Dawson's expertise. Sorrowful that he never unearthed a major discovery, he created the Piltdown Man which resulted in his election to the Royal Society.

Although there is not a substantial amount of evidence, many believe that he received aid from other experts such as Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

, who worked with Dawson on early excavations, and Sir Arthur Smith Woodward who is Keeper of the Department at the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

, friend of Dawson, and co-author of the announcement of Piltdown II.

References

Sources

* De Groote, Isabelle, et al (2016). "New genetic and morphological evidence suggests a single hoaxer created 'Piltdown man'." Royal Society. * Donovan, Stephen K (2016). "The triumph of the Dawsonian method." Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. * Langdon, J.H. (2016). "Case Study 4. Self-Correcting Science: The Piltdown Forgery." In: The Science of Human Evolution. Springer, Cham. * Oakley, Kenneth P., and J. S. Weiner (1995). “Piltdown Man.” Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society. * Ormrod, Tess (2012). "New fossils from a classic area: the Builth Inlier." Hastings & District Geological Society Journal. * Russell, Miles (2003). "Charles Dawson: 'The Piltdown faker'." ''BBC News.'' * Russell, Miles (2003). ''Piltdown Man: The Secret Life of Charles Dawson.'' Stroud: Tempus * * * * Thomson, Keith Stewart (1991). “Marginalia: Piltdown Man: The Great English Mystery Story.” Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society. *Further reading

* *External links

Project Piltdown

at

Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University is a public university in Bournemouth, England, with its main campus situated in neighbouring Poole. The university was founded in 1992; however, the origins of its predecessor date back to the early 1900s.

The univer ...

Archive of Piltdown-related papers

at Clark University

Annotated bibliography of Piltdown Man materials

by T. H. Turrittin – See especially section 15 related to Charles Dawson

Reevaluation of a supposedly Roman iron figure

found by Charles Dawson, but later determined not to be Roman *

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-37021144 "Piltdown review points decisive finger at forger Dawson" BBC News {{DEFAULTSORT:Dawson, Charles 1864 births 1916 deaths Amateur archaeologists Deaths from sepsis Pseudoarchaeologists Archaeological forgery Forgers Hoaxers Writers from Preston, Lancashire