Charles Chiniquy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

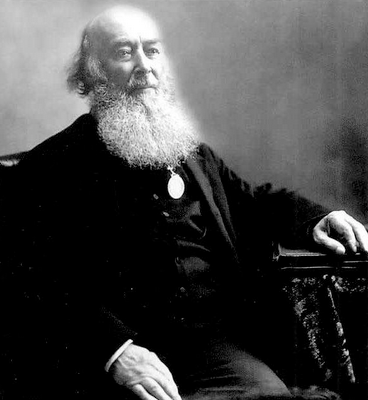

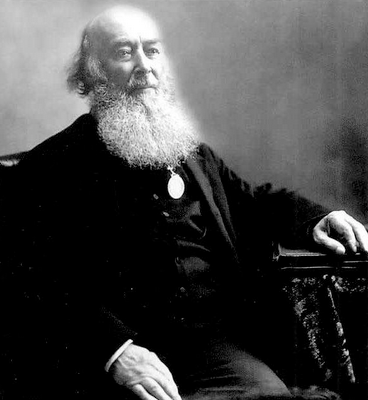

Charles Paschal Telesphore Chiniquy (30 July 1809 – 16 January 1899) was a Canadian socio-

Charles Paschal Telesphore Chiniquy (30 July 1809 – 16 January 1899) was a Canadian socio-

Chiniquy's personal archive

Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Chiniquy, Charles 1809 births 1899 deaths 19th-century Canadian non-fiction writers 19th-century Presbyterian ministers 19th-century Canadian Roman Catholic priests Abraham Lincoln American Calvinist and Reformed ministers American evangelicals American people of French-Canadian descent American Presbyterian ministers American temperance activists Anti-Catholic activists Anti-Catholicism in the United States Canadian Calvinist and Reformed ministers Canadian conspiracy theorists Canadian evangelicals Canadian Presbyterian ministers Canadian temperance activists Christian conspiracy theorists Christian temperance movement Critics of the Catholic Church Converts to Calvinism from Roman Catholicism Converts to evangelical Christianity from Roman Catholicism French Calvinist and Reformed ministers French evangelicals French Quebecers Laicized Roman Catholic priests People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Bas-Saint-Laurent Pre-Confederation Canadian emigrants to the United States Pre-Confederation Quebec people Pseudohistorians

Charles Paschal Telesphore Chiniquy (30 July 1809 – 16 January 1899) was a Canadian socio-

Charles Paschal Telesphore Chiniquy (30 July 1809 – 16 January 1899) was a Canadian socio-political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

activist and former Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

who left the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and converted to Protestant Christianity

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to ...

, becoming a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

minister. He rode the lecture circuit in the United States denouncing the Roman Catholic Church. His themes were that Roman Catholicism was Pagan, that Roman Catholics worshipped the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, and that its theology was anti-Christian.

Chiniquy founded the St. Anne Colony, a village

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred ...

located in Kankakee County

Kankakee County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 113,449. Its county seat is Kankakee. Kankakee County comprises the Kankakee, IL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

St ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

in 1851. ''Fifty Years in the Church of Rome'', an extensive autobiographical account of his life and thoughts as a priest in the Roman Catholic Church, was written by Chiniquy and published in 1886. He warned of plots by the Vatican to take control of the United States by importing Roman Catholic immigrants from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and suggested that the Vatican was behind the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.

Biography

Chiniquy was born in 1809 to a French-Canadian family in the village of Kamouraska,Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

. He lost his father at an early age and was adopted by his uncle. As a young man, Chiniquy studied to become a Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

at the Petit Seminaire ( Little Seminary) in Nicolet, Quebec. He was ordained in 1833; after his ordination, he served his church in Quebec. During the 1840s, he led a campaign throughout Quebec against the consumption of alcohol and drunkenness

Alcohol intoxication, also known as alcohol poisoning, commonly described as drunkenness or inebriation, is the negative behavior and physical effects caused by a recent consumption of alcohol. In addition to the toxicity of ethanol, the main ...

.

Later he immigrated to Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

in the United States. In 1855, Chiniquy was sued by a prominent Catholic layman named Peter Spink in Kankakee, Illinois. After the fall court term, Spink applied for a change of venue to the court in Urbana, Illinois

Urbana ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Champaign County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2020 census, Urbana had a population of 38,336. As of the 2010 United States Census, Urbana is the 38th-most populous municipality in Illinois. It ...

. Chiniquy hired the then-lawyer Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, the future 16th President of the United States, to defend him. The spring court action in Urbana was the highest profile libel suit in Lincoln's career. The case was ended in the fall court session by agreement.

Chiniquy clashed with the Bishop of Chicago, Anthony O'Regan, over the bishop's treatment of Roman Catholics in the city, particularly French Canadians. He declared that O'Regan was secretly backing Spink's suit against him. Chiniquy said that in 1856, O'Regan had threatened him with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

if he did not go to a new location where the bishop wanted to assign him. Several months later, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' published a pastoral letter from O'Regan in which he stated that he had suspended Chiniquy. Since Chiniquy had continued his normal duties as a priest, the bishop excommunicated him by his letter; he vigorously disputed that he had been excommunicated, saying publicly that the bishop was mistaken. Chiniquy left the Roman Catholic Church in 1858, and subsequently converted to Protestant Christianity

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to ...

, becoming a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

minister in 1860.

He asserted that Roman Catholicism was Pagan, that Roman Catholics worshipped the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, and that its theology was anti-Christian. He warned of plots by the Vatican to take control of the United States by importing Roman Catholic immigrants from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. This was at a time of high immigration rates from those countries, in response to social and political upheaval (the Great Famine in Ireland and revolutions in Germany and France). Chiniquy claimed that he was falsely accused by his superiors (and that Abraham Lincoln had come to his rescue), that the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

was a plot against the United States of America by the Vatican, and that the Vatican was behind the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

cause, and the assassination of U.S. President Lincoln, and that Lincoln's assassins were faithful Roman Catholics ultimately serving Pope Pius IX.

After leaving the Roman Catholic Church, Chiniquy dedicated his life to preach and evangelize among his fellow French Canadians, as well as other people in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, in order to convert them from Roman Catholicism to Protestant Christianity

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to ...

. He wrote a number of books and tracts expressing his criticism and views on the alleged errors in the faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. His two most influential literary works are the autobiography ''Fifty Years in The Church of Rome'' and the polemical treatise ''The Priest, The Woman, and The Confessional''. These books raised concerns in the United States about the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. According to one Canadian biographer, Chiniquy is Canada's best-selling author of all time. He joined the Orange Order and said of it: "I always found them staunch and true. I consider it a great honour to be an Orangeman. Every time I go on my knees I pray that God may bless them and make them as numerous and bright as the stars of the heaven above." He died in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-pe ...

, Canada on January 16, 1899.

To this day, some of Chiniquy's works are still promoted among Protestant Christians and ''Sola scriptura

, meaning by scripture alone, is a Christian theological doctrine held by most Protestant Christian denominations, in particular the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, that posits the Bible as the sole infallible source of aut ...

'' believers. One of his most well-known modern day followers was the American Fundamentalist cartoonist and comic book writer Jack Chick

Jack Thomas Chick (April 13, 1924 – October 23, 2016) was an American cartoonist and publisher, best known for his fundamentalist Christian "Chick tracts". He expressed his perspective on a variety of issues through sequential-art morali ...

, notable for being the creator of the "Chick tracts

Chick tracts are short evangelicalism, evangelical gospel tract (literature), tracts, originally created by American publisher and religious cartoonist Jack Chick in the 1960s. His company Chick Publications has continued to print these tracts, ...

"; he also published a comic-form adaptation of Chiniquy's autobiography ''Fifty Years in The Church of Rome'', titled "The Big Betrayal". Chick strongly relied on Chiniquy's claims and books for writing his own anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

tracts.

St. Anne Colony

Chiniquy, then a Roman Catholic priest, left Canada in the wake of a series of scandals. He was offered a fresh start byJames Oliver Van de Velde

James Oliver Van de Velde (April 3, 1795 – November 13, 1855) was a U.S. Catholic bishop born in Belgium. He served as the second Roman Catholic Bishop of Chicago between 1849 and 1853. He traveled to Rome in 1852 and petitioned the Pope for a ...

, Bishop of Chicago, after Ignace Bourget

Ignace Bourget (October 30, 1799 – June 8, 1885) was a Canadian Roman Catholic priest who held the title of Bishop of Montreal from 1840 to 1876. Born in Lévis, Quebec, in 1799, Bourget entered the clergy at an early age, undertook several cou ...

, Bishop of Montreal, asked him to leave in 1851. Chiniquy founded and settled in St. Anne Colony, a village

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred ...

located in Kankakee County

Kankakee County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 113,449. Its county seat is Kankakee. Kankakee County comprises the Kankakee, IL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

St ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

in 1851. Chiniquy was suspended on 19 August 1856, for public insubordination by Bishop Anthony O'Regan, Van de Velde's successor in Chicago. Because he continued to celebrate Mass and administer the other sacraments, he was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

on 3 September 1856. About two years later, on 3 August 1858, O'Regan's successor, Bishop James Duggan

James Duggan (May 22, 1825 – March 27, 1899) was an Irish-American prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as the fourth bishop of the Diocese of Chicago from 1859 to 1869, officially resigning in 1880.

Biography

Early years

James D ...

, formally and publicly reconfirmed Chiniquy's excommunication in St. Anne.

Chiniquy had definitively left the Roman Catholic Church in 1858, and subsequently converted to Protestant Christianity

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to ...

in 1860. Along with many followers, he joined the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America

The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) was the first national Presbyterian denomination in the United States, existing from 1789 to 1958. In that year, the PCUSA merged with the United Presbyterian Church of North Americ ...

(PCUSA). He was admitted as a Presbyterian minister

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance ("ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session or ...

on 1 February 1860. Within two years, Chiniquy, in trouble with the Presbytery of Chicago over his administration of charity funds and a college, according to Elizabeth Ann Kerr McDougall in the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'', sought a new connection in order to avoid an expensive presbytery trial. The college is identified in the ''Seventh Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Illinois'' as Saviour's College, founded in 1860; it is listed neither in ''Universities and Colleges'' nor ''Academies and Seminaries of various grades and courses,'' but in the ''Theological Seminaries and Church Schools'' class of institutions. The report states it "is designed to supply the educational wants of the colony brought by Father Chiniquy from Canada to this State, and to prepare men who will be fitted to preach the gospel in the regions whence he came." The report also quotes a description of the school, attributed to correspondence from a Montreal newspaper, unnamed in the report, that people, also unnamed in the report, "examined the day school

A day school — as opposed to a boarding school — is an educational institution where children and adolescents are given instructions during the day, after which the students return to their homes. A day school has full-day programs when compa ...

or college, as the people there delight to call it" and wrote that it had five classes, ranging from students learning the alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syllab ...

to students learning the "intricacies of French and English grammar

English grammar is the set of structural rules of the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses, Sentence (linguistics), sentences, and whole texts.

This article describes a generalized, present-day Standard English ...

, composition

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

*Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include v ...

, and the other studies of the school, besides the elements of Algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

."

Alexander F. Kemp was chairman of the Synod of the Canada Presbyterian Church committee that examined Chiniquy's application for admission as a minister. According to Kemp, Chiniquy was involved in both presbytery and civil court proceedings connected with the administration of charitable funds and with what Kemp described as an educational institute. The Presbytery of Chicago charged him with un-ministerial and un-Christian conduct; Chiniquy was expected to answer these charges before the presbytery. At that stage of the proceedings, he and his congregation resolved to separate from the Presbytery of Chicago and the Old School (PCUSA), and to request recognition from the Canada Presbyterian Church. Reprinted from the ''Canada Observer.'' The Presbytery of Chicago charged Chiniquy with misrepresenting that a real college was in operation in St. Anne. After conducting an inquiry, Kemp suggested that Chiniquy and his congregation be admitted into the Canada Presbyterian Church.

In St. Anne, a religious society was incorporated in the state that was named the "Christian Catholic Church at St. Anne". It was classified as a Protestant religious association. Two years later, when it joined the PCUSA in 1860, it took the name of "First Presbyterian Church of St. Anne".

See also

Archives

There is a Charles Chiniquyfonds

In archival science, a fonds is a group of documents that share the same origin and that have occurred naturally as an outgrowth of the daily workings of an agency, individual, or organization. An example of a fonds could be the writings of a poe ...

at Library and Archives Canada. The archival reference number is R7160.

References

Bibliography

* * Caroline B. Brettell, ''Following Father Chiniquy: Immigration, Religious Schism, and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century Illinois'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 2015). * Richard Lougheed, ''The Controversial Conversion of Charles Chiniquy'', Toronto, Clements Academic, 2009. * Richard Lougheed, ''Charles Chiniquy : l'homme de controverse'', Toronto, Clements Academic, 2015. * Serup Paul, ''Who Killed Abraham Lincoln?'', Prince George, Salmova Press, 2010. * Marcel Trudel, ''Chiniquy'', Trois-Rivieres, Editions du Bien Public, 1955.External links

Chiniquy's personal archive

Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Chiniquy, Charles 1809 births 1899 deaths 19th-century Canadian non-fiction writers 19th-century Presbyterian ministers 19th-century Canadian Roman Catholic priests Abraham Lincoln American Calvinist and Reformed ministers American evangelicals American people of French-Canadian descent American Presbyterian ministers American temperance activists Anti-Catholic activists Anti-Catholicism in the United States Canadian Calvinist and Reformed ministers Canadian conspiracy theorists Canadian evangelicals Canadian Presbyterian ministers Canadian temperance activists Christian conspiracy theorists Christian temperance movement Critics of the Catholic Church Converts to Calvinism from Roman Catholicism Converts to evangelical Christianity from Roman Catholicism French Calvinist and Reformed ministers French evangelicals French Quebecers Laicized Roman Catholic priests People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Bas-Saint-Laurent Pre-Confederation Canadian emigrants to the United States Pre-Confederation Quebec people Pseudohistorians