Charlemagne Péralte on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charlemagne Masséna Péralte (1886 – 1 November 1919) was a Haitian

Charlemagne Masséna Péralte (1886 – 1 November 1919) was a Haitian

After two years of guerrilla warfare, leading Péralte to declare a

After two years of guerrilla warfare, leading Péralte to declare a

Charlemagne Masséna Péralte (1886 – 1 November 1919) was a Haitian

Charlemagne Masséna Péralte (1886 – 1 November 1919) was a Haitian nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

leader who opposed the United States occupation of Haiti

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 U.S. Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, to take control of ...

in 1915. Leading guerrilla fighters called the Cacos, he posed such a challenge to the US forces in Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

that the occupying forces had to upgrade their presence in the country; he was eventually killed by American troops. Péralte remains a highly praised hero in Haiti.

Early life

Péralte was born October 10th 1885 (or 1886) in the city of Hinche. His father was General Remi Massena Peralte.Guerrilla resistance

An officer by career, Charlemagne Péralte was the military chief of the city ofLéogâne

Léogâne ( ht, Leyogàn) is one of the coastal communes in Haiti. It is located in the eponymous Léogâne Arrondissement, which is part of the Ouest Department. The port town is located about west of the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. L ...

when the US Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through comb ...

invaded Haiti in July 1915.

Refusing to surrender to foreign troops without fighting, Péralte resigned from his position and returned to his native town of Hinche to take care of his family's land. In 1917, he was arrested for a botched raid on the Hinche gendarmerie payroll, and was sentenced to five years of forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. Escaping his captivity, Charlemagne Péralte gathered a group of nationalist rebels and started guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

against the US troops.

The troops led by Péralte were called "Cacos", a name that harked back to rural troops that historically took part in the political turmoil of late 19th century Haiti. The guerrilla warriors of the Cacos were such strong adversaries that the United States upgraded the US Marine contingent in Haiti and even employed airplanes for counter-guerrilla warfare. His forces attacked Port-au-Prince in 1919, but were driven off.

Death and aftermath

After two years of guerrilla warfare, leading Péralte to declare a

After two years of guerrilla warfare, leading Péralte to declare a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

in the north of Haiti, Charlemagne Péralte was betrayed by one of his officers, Jean-Baptiste Conzé, who led disguised US Marines Sergeant Herman H. Hanneken

Herman Henry Hanneken (June 23, 1893 – August 23, 1986) was a United States Marine Corps officer and a recipient of the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor.

Beginning his career as an enlisted man, Hanneken served in the Bana ...

(later meritoriously promoted to Second Lieutenant for his exploits) and Corporal William Button into the rebels camp, near Grande-Rivière-du-Nord

Grande-Rivière-du-Nord ( ht, Grann Rivyè dinò) is a commune in the Grande-Rivière-du-Nord Arrondissement, in the Nord Department of Haiti. Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 Sept ...

.Musicant, I, The Banana Wars, 1990, New York: MacMillan Publishing Co.,

Péralte was shot in the heart at close range. Hanneken and his men then fled with Peralte's body strapped onto a mule.

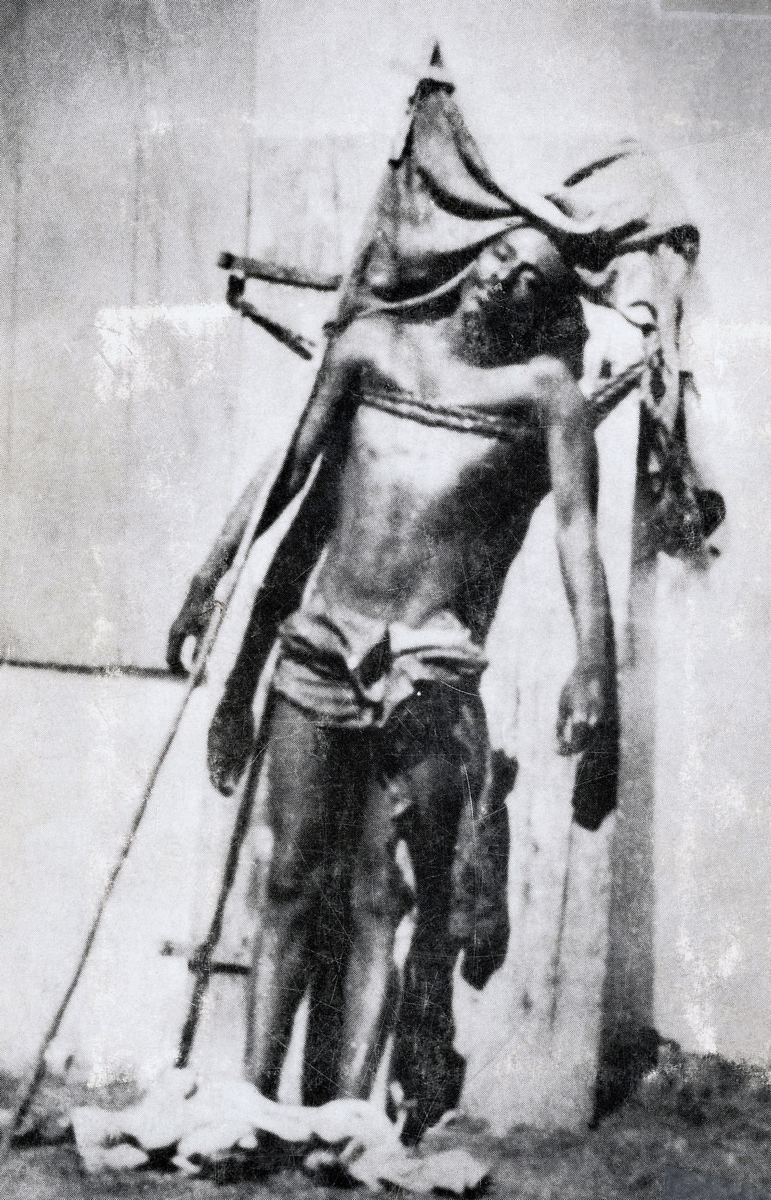

In order to discourage rebel support from the Haitian population, the US troops took a picture of Charlemagne Péralte's body tied to a door, and distributed it in the country. However, it had the opposite effect, with the image's resemblance to a crucifixion making it an icon of the resistance and establishing Péralte as a martyr.

Charlemagne Péralte's remains were unearthed after the end of the US occupation in 1935. A national funeral, attended by the then-President of Haiti

The president of Haiti ( ht, Prezidan peyi Ayiti, french: Président d'Haïti), officially called the president of the Republic of Haiti (french: link=no, Président de la République d'Haïti, ht, link=no, Prezidan Repiblik Ayiti), is the head ...

, Sténio Vincent

Sténio Joseph Vincent (February 22, 1874 – September 3, 1959) was President of Haiti from November 18, 1930 to May 15, 1941.

Biography

Sténio Vincent was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. His parents were Benjamin Vincent and Iramène Brea, wh ...

, was held in Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ht, Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as or , is a commune of about 190,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previousl ...

, where his grave can still be seen today.

A portrait of Charlemagne Péralte can now be seen on the Haitian coins issued by the government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide

Jean-Bertrand Aristide (born 15 July 1953) is a Haitian former Salesian priest and politician who became Haiti's first democratically elected president. A proponent of liberation theology, Aristide was appointed to a parish in Port-au-Prince ...

after his 1994 return under the protection of US troops.

Consequently, for their daring exploit, Corporal Button (1895–1921) and Sergeant Hanneken (1893–1986) were both awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

for killing the "supreme bandit

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, and murder, either as an ...

of Haiti". Hanneken later served in World War II, notably at Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

and ended his career as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

. In his later days, he constantly declined to comment on his exploits in Haiti, notably to Haitian journalists asking for interviews on the 100th anniversary of Péralte's birth, in 1986.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Peralte, Charlemagne 1880s births 1919 deaths Haitian nationalists Haitian rebels Haitian people of Mulatto descent People from Hinche Deaths by firearm in Haiti Guerrillas killed in action Haitian independence activists People of the Banana Wars