Century 21 Exposition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Century 21 Exposition (also known as the Seattle World's Fair) was a

, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Nearly 10 million people attended the fair.Joel Connelly

Century 21 introduced Seattle to its future

, ''

, HSTAA 432: History of Washington State and the Pacific Northwest, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington. Accessed online October 18, 2007. as "an aerospace city", a major theme of the fair was to show that "the United States was not really 'behind' the Soviet Union in the realms of science and space". As a result, the themes of space, science, and the future completely trumped the earlier conception of a "Festival of the

A model for the future

, ''

, HSTAA 432: History of Washington State and the Pacific Northwest], Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington. Accessed online April 9, 2011.

Once the fair idea was conceived, several sites were considered. Among the sites considered within Seattle were

Once the fair idea was conceived, several sites were considered. Among the sites considered within Seattle were  The site finally selected for the Century 21 Exposition had originally been contemplated for a civic center. The idea of using it for the world's fair came later and brought in federal money for the United States Science Pavilion (now Pacific Science Center) and state money for the Washington State Coliseum (later Seattle Center Coliseum; renamed KeyArena in 1993 after the city sold naming rights to KeyCorp, the company doing business as KeyBank; renamed

The site finally selected for the Century 21 Exposition had originally been contemplated for a civic center. The idea of using it for the world's fair came later and brought in federal money for the United States Science Pavilion (now Pacific Science Center) and state money for the Washington State Coliseum (later Seattle Center Coliseum; renamed KeyArena in 1993 after the city sold naming rights to KeyCorp, the company doing business as KeyBank; renamed

"Century 21: Forward into the Past", "cybertour" of the exposition, HistoryLink.org. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Interview with Paul Thiry Conducted by Meredith Clausen at the Artist's home September 15 & 16, 1983

Smithsonian, Archives of American Art. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Some of the land had been donated to the city by James Osborne in 1881 and by David and Louisa Denny in 1889.Campus Walking Tour / Narrative for Seattle Center

, Seattle Center. Accessed online October 19, 2007. Two lots at Third Avenue N. and John Street were purchased from St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church, who had been planning to build a new church building there; the church used the proceeds to purchase land in the Montlake neighborhood. The Warren Avenue School, a public elementary school with several programs for physically handicapped students, was torn down, its programs dispersed, and provided most of the site of the Coliseum (now Climate Pledge Arena). Near the school, some of the city's oldest houses, apartments, and commercial buildings were torn down; they had been run down to the point of being known as the "Warren Avenue slum". The old Fire Station No. 4 was also sacrificed.Lentz and Sheridan, 2005, p. 23. As early as the 1909 Bogue plan, this part of Lower Queen Anne had been considered for a civic center. The Civic Auditorium (later the Opera House, now McCaw Hall), the ice arena (later Mercer Arena), and the Civic Field (rebuilt in 1946 as the High School Memorial Stadium), all built in 1927 had been placed there based on that plan, as was an armory (the Food Circus during the fair, later Center House). The fair planners also sought two other properties near the southwest corner of the grounds. They failed completely to make any inroads with the Seattle Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, who had recently built Sacred Heart Church there; they did a bit better with the

The fair planners also sought two other properties near the southwest corner of the grounds. They failed completely to make any inroads with the Seattle Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, who had recently built Sacred Heart Church there; they did a bit better with the

Yamasaki, Minoru (1912–1986), Seattle-born architect of New York's World Trade Center

, HistoryLink.org Essay 5352, March 3, 2003. Accessed online October 18, 2007.

The World of Science centered on the United States Science Exhibit. It also included a

The World of Science centered on the United States Science Exhibit. It also included a

During the festival, the building hosted several exhibits. Nearly half of its surface area was occupied by the state's own circular exhibit "Century 21—The Threshold and the Threat", also known as the "World of Tomorrow" exhibit, billed as a "21-minute tour of the future". The building also housed exhibits by France,

During the festival, the building hosted several exhibits. Nearly half of its surface area was occupied by the state's own circular exhibit "Century 21—The Threshold and the Threat", also known as the "World of Tomorrow" exhibit, billed as a "21-minute tour of the future". The building also housed exhibits by France,  The exhibit continued with a vision of future transportation (centered on a

The exhibit continued with a vision of future transportation (centered on a

Foreign exhibits included a science and technology exhibit by Great Britain, while Mexico and Peru focused on handicrafts, and Japan and India attempted to show both of these sides of their national cultures. The

Foreign exhibits included a science and technology exhibit by Great Britain, while Mexico and Peru focused on handicrafts, and Japan and India attempted to show both of these sides of their national cultures. The

The Fine Arts Pavilion (later the Exhibition Hall) brought together an art exhibition unprecedented for the

The Fine Arts Pavilion (later the Exhibition Hall) brought together an art exhibition unprecedented for the  A separate gallery presented Northwest Coast Indian art, and featured a series of large paintings by Bill Holm introducing Northwest Native motifs.

A separate gallery presented Northwest Coast Indian art, and featured a series of large paintings by Bill Holm introducing Northwest Native motifs.

Events and performances at the Playhouse included Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre; a chamber music performance by

Events and performances at the Playhouse included Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre; a chamber music performance by

;Gayway: The Gayway was a small amusement park; after the fair it became the Fun Forest. It included such rides as the Flight to Mars, a dark amusement ride themed around space pirates on Mars, decorated with

;Gayway: The Gayway was a small amusement park; after the fair it became the Fun Forest. It included such rides as the Flight to Mars, a dark amusement ride themed around space pirates on Mars, decorated with

Official website of the BIEA "cybertour" of the exposition

at HistoryLink.

Century 21 – The 1962 Seattle World's Fair

at HistoryLink

Century 21 Digital Collection from the Seattle Public Library

– over 1800 related photos, advertisements, reports, programs, postcards, brochures, and more. *"Seattle Center", p. 18–24 i

Survey Report: Comprehensive Inventory of City-Owned Historic Resources, Seattle, Washington

Department of Neighborhoods (Seattle) Historic Preservation, offers an extremely detailed account of the acquisition of land for the exposition and of past and present buildings on the grounds.

Seattle Photographs Collection, Century 21 Exposition

– University of Washington Digital Collection

Pamphlet and Textual Ephemera Collection, Century 21 Exposition documents

– University of Washington Digital Collection {{Coord, 47, 37, 17, N, 122, 21, 03, W, format=dms, display=title, type:landmark_region:US-WA Seattle Center History of the West Coast of the United States 1962 in Washington (state) 1960s in Seattle Articles containing video clips

world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

held April 21, 1962, to October 21, 1962, in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, United States.Guide to the Seattle Center Grounds Photograph Collection: April, 1963, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Nearly 10 million people attended the fair.Joel Connelly

Century 21 introduced Seattle to its future

, ''

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

The ''Seattle Post-Intelligencer'' (popularly known as the ''Seattle P-I'', the ''Post-Intelligencer'', or simply the ''P-I'') is an online newspaper and former print newspaper based in Seattle, Washington, United States.

The newspaper was fo ...

'', April 16, 2002. Accessed online October 18, 2007.

As planned, the exposition left behind a fairground and numerous public buildings and public works; some credit it with revitalizing Seattle's economic and cultural life (''see History of Seattle since 1940''). The fair saw the construction of the Space Needle

The Space Needle is an observation tower in Seattle, Washington, United States. Considered to be an icon of the city, it has been designated a Seattle landmark. Located in the Lower Queen Anne neighborhood, it was built in the Seattle Cente ...

and Alweg monorail, as well as several sports venues (Washington State Coliseum, now Climate Pledge Arena

Climate Pledge Arena is a multi-purpose indoor arena in Seattle, Washington, United States. It is located north of Downtown Seattle in the entertainment complex known as Seattle Center, the site of the 1962 World's Fair, for which it was ori ...

) and performing arts buildings (the Playhouse, now the Cornish Playhouse), most of which have since been replaced or heavily remodeled. Unlike some other world's fairs of its era, Century 21 made a profit.

The site, slightly expanded since the fair, is now called Seattle Center

Seattle Center is an arts, educational, tourism and entertainment center in Seattle, Washington, United States. Spanning an area of 74 acres (30 ha), it was originally built for the 1962 World's Fair. Its landmark feature is the tall Space Needle ...

; the United States Science Pavilion is now the Pacific Science Center

Pacific Science Center is an independent, non-profit science center in Seattle with a mission to ignite curiosity and fuel a passion for discovery, experimentation, and critical thinking. Pacific Science Center serves more than 1 million people e ...

. Another notable Seattle Center building, the Museum of Pop Culture

The Museum of Pop Culture or MoPOP is a nonprofit museum in Seattle, Washington, dedicated to contemporary popular culture. It was founded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2000 as the Experience Music Project. Since then MoPOP has organ ...

(earlier called EMP Museum), was built nearly 40 years later and designed to fit in with the fairground atmosphere.

Planning and funding

Seattle mayorAllan Pomeroy

Merritt "Allan" Pomeroy – (1907-July 7, 1966) was the forty-third mayor of Seattle, Washington serving from June 1, 1952 to June 4, 1956.

Early life

Pomeroy was born in Astoria, Oregon, and later moved with his parents to the state of Washingt ...

is credited with bringing the World's Fair to the city. He recruited community and business leaders, as well as running a petition campaign, in the early 1950s to convince the city council to approve an $8.5 million bond issue to build the opera house and sports center needed to attract the fair. Eventually the council approved a $7.5 million bond issue with the state of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

matching that amount.

Cold War and Space Race context

The fair was originally conceived at aWashington Athletic Club

The Washington Athletic Club, founded in 1930, is a private social and athletic club located in downtown Seattle. The 21-story WAC clubhouse opened in December 1930, and was designed in the Art Deco style by Seattle architect Sherwood D. Ford.

...

luncheon in 1955 to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1909 Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition

The Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition, acronym AYP or AYPE, was a world's fair held in Seattle in 1909 publicizing the development of the Pacific Northwest. It was originally planned for 1907 to mark the 10th anniversary of the Klondike Gold R ...

, but it soon became clear that that date was too ambitious. With the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

underway and Boeing

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and ...

having "put Seattle on the map"Lesson Twenty-five: The Impact of the Cold War on Washington: The 1962 Seattle World's Fair, HSTAA 432: History of Washington State and the Pacific Northwest, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington. Accessed online October 18, 2007. as "an aerospace city", a major theme of the fair was to show that "the United States was not really 'behind' the Soviet Union in the realms of science and space". As a result, the themes of space, science, and the future completely trumped the earlier conception of a "Festival of the

merican

''Merican'' is an EP by the American punk rock band the Descendents, released February 10, 2004. It was the band's first release for Fat Wreck Chords and served as a pre-release to their sixth studio album ''Cool to Be You'', released the follo ...

West".

In June 1960, the Bureau International des Expositions

The Bureau international des expositions (BIE; English: International Bureau of Expositions) is an intergovernmental organization created to supervise international exhibitions (also known as expos or world expos) falling under the jurisdiction ...

(BIE) certified Century 21 as a world's fair. Project manager Ewen Dingwall went to Moscow to request Soviet participation, but was turned down. Neither the People's Republic of China, Vietnam nor North Korea were invited.Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghyA model for the future

, ''

The Seattle Times

''The Seattle Times'' is a daily newspaper serving Seattle, Washington, United States. It was founded in 1891 and has been owned by the Blethen family since 1896. ''The Seattle Times'' has the largest circulation of any newspaper in Washington ...

'', September 22, 1996. Accessed online October 20, 2007.

As it happened, the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

had an additional effect on the fair. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

was supposed to attend the closing ceremony of the fair on October 21, 1962. He bowed out, pleading a "heavy cold"; it later became public that he was dealing with the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

.

The fair's vision of the future displayed a technologically based optimism that did not anticipate any dramatic social change, one rooted in the 1950s rather than in the cultural tides that would emerge in the 1960s. Affluence, automation, consumerism, and American power would grow; social equity would simply take care of itself on a rising tide of abundance; the human race would master nature through technology rather than view it in terms of ecology. In contrast, 12 years later—even in far more conservative Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the ...

—Expo '74

Expo '74, officially known as the International Exposition on the Environment, Spokane 1974, was a world's fair held May 4, 1974, to November 3, 1974 in Spokane, Washington in the northwest United States. It was the first environmentally themed ...

took environmentalism as its central theme. The theme of Spokane's Expo '74 was "Celebrating Tomorrow's Fresh New Environment.".Lesson Twenty-six: Spokane's Expo '74: A World's Fair for the Environment, HSTAA 432: History of Washington State and the Pacific Northwest], Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington. Accessed online April 9, 2011.

Buildings and grounds

Once the fair idea was conceived, several sites were considered. Among the sites considered within Seattle were

Once the fair idea was conceived, several sites were considered. Among the sites considered within Seattle were Duwamish Head

Duwamish Head is the northernmost point in West Seattle, Washington, jutting into Elliott Bay. The Duwamish called it "Low Point" or "Base of the Point" ( Lushootseed: sgWudaqs).

A large boulder covered with petroglyphs once lay on the beach. Th ...

in West Seattle

West Seattle is a conglomeration of neighborhoods in Seattle, Washington, United States. It comprises two of the thirteen districts, Delridge and Southwest, and encompasses all of Seattle west of the Duwamish River. It was incorporated as an i ...

; Fort Lawton

Fort Lawton was a United States Army post located in the Magnolia neighborhood of Seattle, Washington overlooking Puget Sound. In 1973 a large majority of the property, 534 acres of Fort Lawton, was given to the city of Seattle and dedicated as ...

(now Discovery Park) in the Magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendr ...

neighborhood; and First Hill—even closer to Downtown

''Downtown'' is a term primarily used in North America by English speakers to refer to a city's sometimes commercial, cultural and often the historical, political and geographic heart. It is often synonymous with its central business district ...

than the site finally selected, but far more densely developed. Two sites south of the city proper were considered— Midway, near Des Moines

Des Moines () is the capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is also the county seat of Polk County. A small part of the city extends into Warren County. It was incorporated on September 22, 1851, as Fort Des Moines ...

, and the Army Depot in Auburn—as was a site east of the city on the south shore of Lake Sammamish

Lake Sammamish is a freshwater lake east of Seattle in King County, Washington, United States. The lake is long and wide, with a maximum depth of and a surface area of . It lies east of Lake Washington and west of the Sammamish Plateau, ...

.

The site finally selected for the Century 21 Exposition had originally been contemplated for a civic center. The idea of using it for the world's fair came later and brought in federal money for the United States Science Pavilion (now Pacific Science Center) and state money for the Washington State Coliseum (later Seattle Center Coliseum; renamed KeyArena in 1993 after the city sold naming rights to KeyCorp, the company doing business as KeyBank; renamed

The site finally selected for the Century 21 Exposition had originally been contemplated for a civic center. The idea of using it for the world's fair came later and brought in federal money for the United States Science Pavilion (now Pacific Science Center) and state money for the Washington State Coliseum (later Seattle Center Coliseum; renamed KeyArena in 1993 after the city sold naming rights to KeyCorp, the company doing business as KeyBank; renamed Climate Pledge Arena

Climate Pledge Arena is a multi-purpose indoor arena in Seattle, Washington, United States. It is located north of Downtown Seattle in the entertainment complex known as Seattle Center, the site of the 1962 World's Fair, for which it was ori ...

in 2021 after naming rights were sold to Amazon.com, Inc).Point 22: World of Tomorrow"Century 21: Forward into the Past", "cybertour" of the exposition, HistoryLink.org. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Interview with Paul Thiry Conducted by Meredith Clausen at the Artist's home September 15 & 16, 1983

Smithsonian, Archives of American Art. Accessed online October 18, 2007. Some of the land had been donated to the city by James Osborne in 1881 and by David and Louisa Denny in 1889.Campus Walking Tour / Narrative for Seattle Center

, Seattle Center. Accessed online October 19, 2007. Two lots at Third Avenue N. and John Street were purchased from St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church, who had been planning to build a new church building there; the church used the proceeds to purchase land in the Montlake neighborhood. The Warren Avenue School, a public elementary school with several programs for physically handicapped students, was torn down, its programs dispersed, and provided most of the site of the Coliseum (now Climate Pledge Arena). Near the school, some of the city's oldest houses, apartments, and commercial buildings were torn down; they had been run down to the point of being known as the "Warren Avenue slum". The old Fire Station No. 4 was also sacrificed.Lentz and Sheridan, 2005, p. 23. As early as the 1909 Bogue plan, this part of Lower Queen Anne had been considered for a civic center. The Civic Auditorium (later the Opera House, now McCaw Hall), the ice arena (later Mercer Arena), and the Civic Field (rebuilt in 1946 as the High School Memorial Stadium), all built in 1927 had been placed there based on that plan, as was an armory (the Food Circus during the fair, later Center House).

The fair planners also sought two other properties near the southwest corner of the grounds. They failed completely to make any inroads with the Seattle Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, who had recently built Sacred Heart Church there; they did a bit better with the

The fair planners also sought two other properties near the southwest corner of the grounds. They failed completely to make any inroads with the Seattle Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, who had recently built Sacred Heart Church there; they did a bit better with the Freemasons

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

' Nile Temple, which they were able to use for the duration of the fair and which then returned to its previous use. It served as the site of the Century 21 Club. This membership organization, formed especially for the fair, charged $250 for membership and offered lounge, dining room, and other club facilities, as well as a gate pass for the duration of the fair. The city ended up leasing the property after the fair and in 1977 bought it from the Masons. The building was eventually incorporated into a theater complex including the Seattle Children's Theatre

The Seattle Children's Theatre (SCT) is a resident theatre for young audiences in Seattle, Washington, founded in 1975. Its main performances are at the Seattle Center in a 482-seat and a 275-seat theatre, from September through June. SCT also has ...

.

Paul Thiry was the fair's chief architect; he also designed the Coliseum building. Among the other architects of the fair, Seattle-born Minoru Yamasaki

was an American architect, best known for designing the original World Trade Center in New York City and several other large-scale projects. Yamasaki was one of the most prominent architects of the 20th century. He and fellow architect Edward ...

received one of his first major commissions to build the United States Science Pavilion. Yamasaki would later design New York's World Trade Center.Walt CrowleyYamasaki, Minoru (1912–1986), Seattle-born architect of New York's World Trade Center

, HistoryLink.org Essay 5352, March 3, 2003. Accessed online October 18, 2007.

Victor Steinbrueck

Victor Eugene Steinbrueck (December 15, 1911 - February 14, 1985) was an American architect, best known for his efforts to preserve Seattle's Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market. He authored several books and was also a University of Washingt ...

and John Graham, Jr. designed the Space Needle. Hideki Shimizu and Kazuyuki Matsushita designed the original International Fountain

The International Fountain, designed by Tokyo-based architects Kazuyuki Matsushita and Hideki Shimizu during 1961–1962 for the Century 21 Exposition (also known as the Seattle World's Fair), is a concrete fountain and sculpture installed in Sea ...

. Despite the plan to build a permanent civic center, more than half the structures built for the fair were torn down more or less immediately after it ended. One attempt to conserve installations from Century 21 was the creation of a replica "welcoming pole," a number of which originally stood tall over the southern entrance to the fair. This replica stood outside the Washington State Capital Museum until 1990, when it was taken down.

The grounds of the fair were divided into:

*World of Science

*World of Century 21 (also known as World of Tomorrow)

*World of Commerce and Industry

*World of Art

*World of Entertainment

*Show Street

*Gayway

*Boulevards of the World

*Exhibit Fair

*Food and Favors

*Food Circus

Source:

Besides the monorail

A monorail (from "mono", meaning "one", and " rail") is a railway in which the track consists of a single rail or a beam.

Colloquially, the term "monorail" is often used to describe any form of elevated rail or people mover. More accurat ...

, which survives , the fair also featured a Skyride that ran across the grounds from the Gayway to the International Mall. The bucket-like three-person cars were suspended from cables that rose as high as off the ground. The Skyride was moved to the Puyallup Fair

The Washington State Fair, formerly the Puyallup Fair, is the largest single attraction held annually in the U.S. state of Washington. It continually ranks in the top ten largest fairs in the United States and includes agricultural and pastor ...

grounds in 1980.

World of Science

The World of Science centered on the United States Science Exhibit. It also included a

The World of Science centered on the United States Science Exhibit. It also included a NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

Exhibit that included models and mockups of various satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioiso ...

s, as well as the Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

capsule that had carried Alan Shepard

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998) was an American astronaut, naval aviator, test pilot, and businessman. In 1961, he became the second person and the first American to travel into space and, in 1971, he beca ...

into space.''Official Guide Book'', pp. 8–24. These exhibits were the federal government's major contribution to the fair.

The United States Science Exhibit began with Charles Eames

Charles Ormond Eames Jr. (June 17, 1907 – August 21, 1978) was an American designer, architect and filmmaker. In professional partnership with his spouse Ray Kaiser Eames, he was responsible for groundbreaking contributions in the field of a ...

' 10-minute short film ''The House of Science'', followed by an exhibit on the development of science, ranging from mathematics and astronomy to atomic science and genetics. The Spacearium held up to 750 people at a time for a simulated voyage first through the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

and then through the Milky Way Galaxy

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye. ...

and beyond. Further exhibits presented the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

and the "horizons of science". This last looked at "Science and the individual", "Control of man's physical surroundings", "Science and the problem of world population

In demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded 8 billion in November 2022. It took over 200,000 years of human prehistory and history for th ...

", and "Man's concept of his place in an increasingly technological world".

World of Century 21

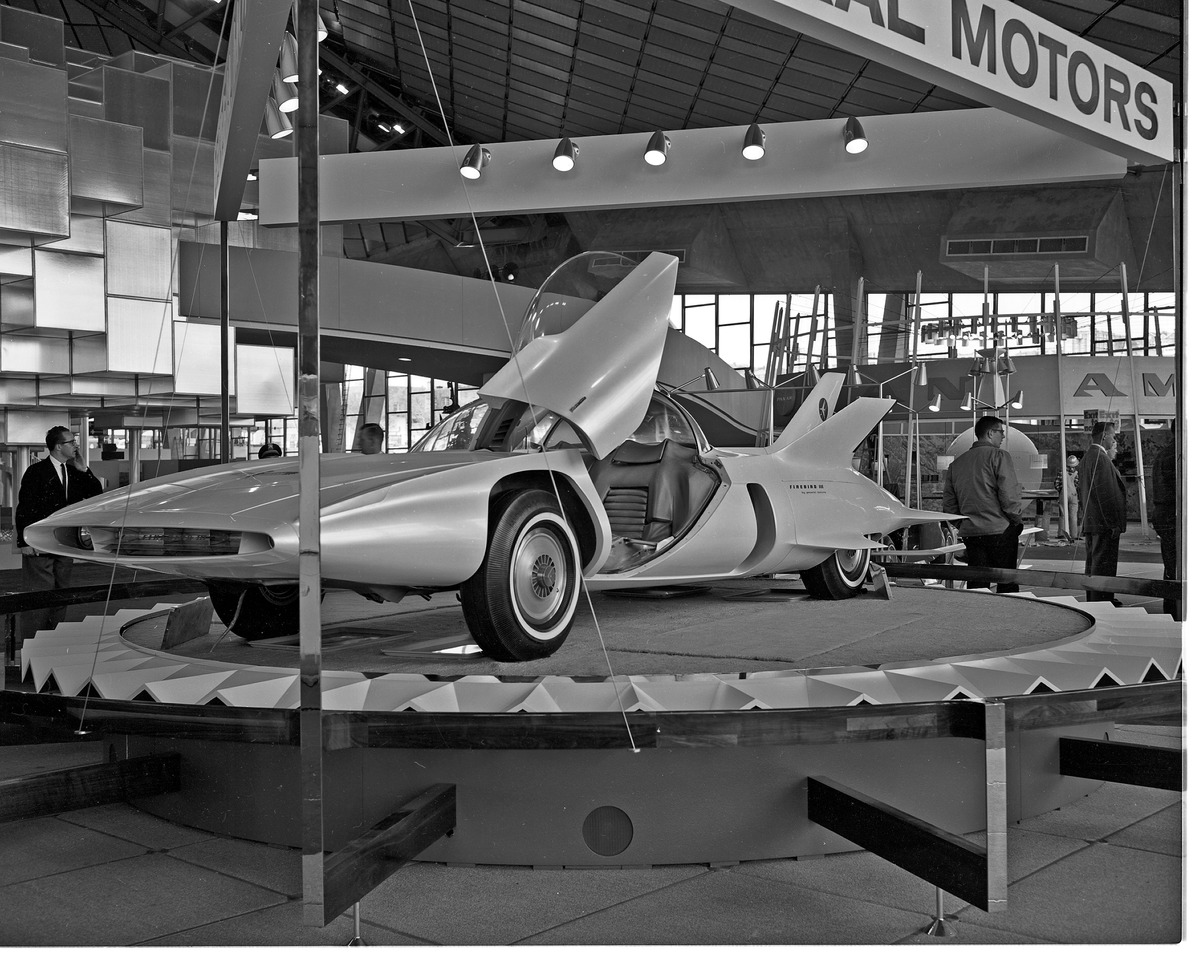

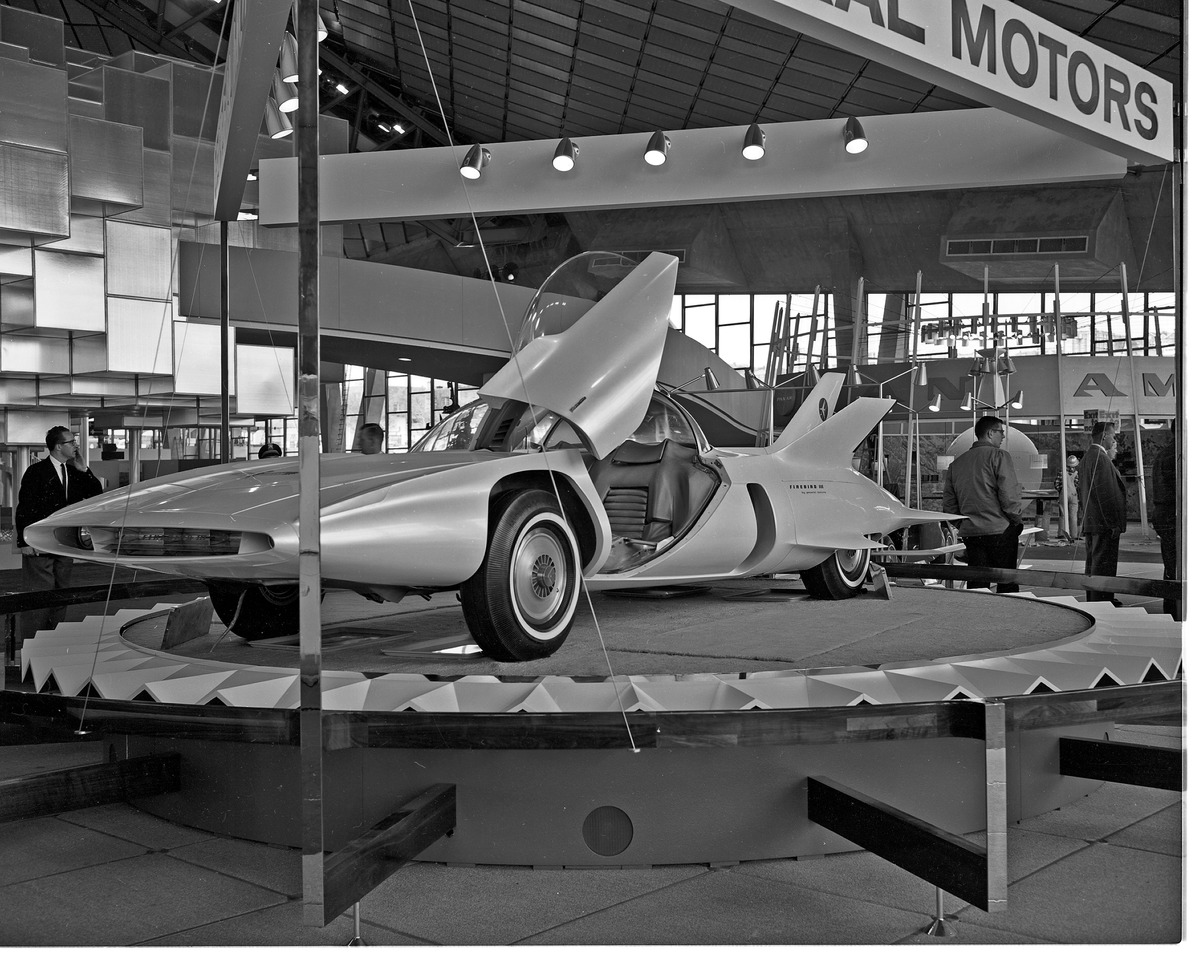

The Washington State Coliseum, financed by the state of Washington, was one of Thiry's own architectural contributions to the fairgrounds. His original conception had been staging the entire fair under a single giant air-conditioned tent-like structure, "a city of its own", but there were neither the budgets nor the tight agreements on concept to realize that vision. In the end, he got exactly enough of a budget to design and build a building suitable to hold a variety of exhibition spaces and equally suitable for later conversion to a sports arena and convention facility. During the festival, the building hosted several exhibits. Nearly half of its surface area was occupied by the state's own circular exhibit "Century 21—The Threshold and the Threat", also known as the "World of Tomorrow" exhibit, billed as a "21-minute tour of the future". The building also housed exhibits by France,

During the festival, the building hosted several exhibits. Nearly half of its surface area was occupied by the state's own circular exhibit "Century 21—The Threshold and the Threat", also known as the "World of Tomorrow" exhibit, billed as a "21-minute tour of the future". The building also housed exhibits by France, Pan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United State ...

(Pan Am), General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

(GM), the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world, with 49,727 members ...

(ALA), and RCA

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Comp ...

, as well as a Washington state tourist center.''Official Guide Book'', pp. 26–34.

In "The Threshold and the Threat", visitors rode a " Bubbleator" into the "world of tomorrow". Music "from another world" and a shifting pattern of lights accompanied them on a 40-second upward journey to a starry space bathed in golden light. Then they were faced briefly with an image of a desperate family in a fallout shelter

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designated to protect occupants from radioactive debris or fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the Cold War.

During ...

, which vanished and was replaced by a series of images reflecting the sweep of history, starting with the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

and ending with an image of Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; 1 June 1926 4 August 1962) was an American actress. Famous for playing comedic " blonde bombshell" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as wel ...

.

Next, visitors were beckoned into a cluster of cubes containing a model of a "city of the future" (which a few landmarks clearly indicated as Seattle) and its suburban and rural surroundings, seen first by day and later by night. The next cluster of cubes zoomed in on a vision of a high-tech, future home in a sylvan setting (and a commuter gyrocopter); a series of projections contrasted this "best of the future" to "the worst of the present" (over-uniform suburbs, a dreary urban housing project).

The exhibit continued with a vision of future transportation (centered on a

The exhibit continued with a vision of future transportation (centered on a monorail

A monorail (from "mono", meaning "one", and " rail") is a railway in which the track consists of a single rail or a beam.

Colloquially, the term "monorail" is often used to describe any form of elevated rail or people mover. More accurat ...

and high-speed "air cars" on an electrically controlled highway). There was also an " office of the future", a climate-controlled "farm factory", an automated offshore kelp

Kelps are large brown algae seaweeds that make up the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera. Despite its appearance, kelp is not a plant - it is a heterokont, a completely unrelated group of organisms.

Kelp grows in "underwa ...

and plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cruc ...

harvesting farm, a vision of the schools of the future with "electronic storehouses of knowledge", and a vision of the many recreations that technology would free humans to pursue.

Finally, the tour ended with a symbolic sculptural tree and the reappearance of the family in the fallout shelter and the sound of a ticking clock, a brief silence, an extract from President Kennedy's Inaugural Address, followed by a further "symphony of music and color".

Under the same roof, the ALA exhibited a "library of the future" (centered on a Univac

UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer) was a line of electronic digital stored-program computers starting with the products of the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation. Later the name was applied to a division of the Remington Rand company an ...

computer). GM exhibited its vision for highways and vehicles of the future (the latter including the Firebird III). Pan Am exhibited a giant globe that emphasized the notion that we had come to be able to think of distances between major world cities in hours and minutes rather than in terms of chancy voyages over great distances. RCA (which produced "The Threshold and the Threat") exhibited television, radio, and stereo technology, as well as its involvement in space. The French government had an exhibit with its own take on technological progress. Finally, a Washington state tourist center provided information for fair-goers wishing to tour the state.

World of Commerce and Industry

The World of Commerce and Industry was divided into domestic and foreign areas. The former was sited mainly south of American Way (the continuation of Thomas Street through the grounds), an area it shared with the World of Science. It included the Space Needle and what is now the Broad Street Green and Mural Amphitheater. The Hall of Industry and some smaller buildings were immediately north of American Way. The latter included 15 governmental exhibitors and surrounded the World of Tomorrow and extended to the north edge of the fair. Among the features of Domestic Commerce and Industry, the massive Interiors, Fashion, and Commerce Building spread for —nearly the entire Broad Street side of the grounds—with exhibits ranging from 32 separate furniture companies to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

''.''Official Guide Book'', pp. 45–68. ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Australia'', an Australian fashion magazine

** ''Vogue China'', ...

'' produced four fashion shows daily alongside a perfumed pool. The Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobi ...

, in its pavilion, presented a simulated space flight and its vision for the car of the future, the Ford Seattle-ite XXI The Ford Seattle-ite XXI was a 3/8 scale concept car designed by Alex Tremulis and displayed on 20 April 1962 on the Ford stand at the Seattle World's Fair.

Description

The car contained novel ideas that have since become reality: interchangeab ...

. The Electric Power Pavilion included a -high fountain made to look like a hydroelectric dam

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined a ...

, with the entrance to the pavilion through a tunnel in said "dam". The Forest Products Pavilion was surrounded by a grove of trees of various species, and included an all-wood theater and a Society of American Foresters

The Society of American Foresters (SAF) is a professional organization representing the forestry industry in the United States. Its mission statement declares that it seeks to "advance the science, education, and practice of forestry; to enhance t ...

exhibit. Standard Oil of California Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object t ...

celebrated, among other things, the fact that the world's first service station opened in Seattle in 1907. The fair's Bell Telephone (now AT&T Inc.) exhibit was featured in a short film called "Century 21 Calling...", which was later shown on ''Mystery Science Theater 3000

''Mystery Science Theater 3000'' (abbreviated as ''MST3K'') is an American science fiction comedy film review television series created by Joel Hodgson. The show premiered on WUCW, KTMA-TV (now WUCW) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on November 24, 1 ...

''. There were also several religious pavilions. Near the center of all this was Seattle artist Paul Horiuchi

Paul Horiuchi (April 12, 1906 – August 29, 1999) was an American painting, painter and collage, collagist. He was born in Oishi, Japan, and studied art from an early age. After immigrating to the United States in his early teens, he spent many ...

's massive mosaic mural, the region's largest work of art at the time, which now forms the backdrop of Seattle Center's Mural Amphitheater.

Foreign exhibits included a science and technology exhibit by Great Britain, while Mexico and Peru focused on handicrafts, and Japan and India attempted to show both of these sides of their national cultures. The

Foreign exhibits included a science and technology exhibit by Great Britain, while Mexico and Peru focused on handicrafts, and Japan and India attempted to show both of these sides of their national cultures. The Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

and South Korea pavilions showed their rapid industrialization to the world and the benefits of capitalism over communism during the time of cold war era. Other pavilions included one featuring Brazilian tea and coffee; a European Communities Pavilion from the then six countries of the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

; and a joint pavilion by those countries of Africa that had by then achieved independence. Sweden's exhibit included the story of the salvaging of a 17th-century man-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

from Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

harbor, and San Marino's exhibit featured its postage stamps and pottery. Near the center of this was the DuPen Fountain featuring three sculptures by Seattle artist Everett DuPen.''Official Guide Book'', pp. 70–84.

World of Art

The Fine Arts Pavilion (later the Exhibition Hall) brought together an art exhibition unprecedented for the

The Fine Arts Pavilion (later the Exhibition Hall) brought together an art exhibition unprecedented for the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S ...

. Among the 50 contemporary American painters whose works shown were Josef Albers

Josef Albers (; ; March 19, 1888March 25, 1976) was a German-born artist and educator. The first living artist to be given a solo show at MoMA and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, he taught at the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College ...

, Willem de Kooning

Willem de Kooning (; ; April 24, 1904 – March 19, 1997) was a Dutch-American abstract expressionist artist. He was born in Rotterdam and moved to the United States in 1926, becoming an American citizen in 1962. In 1943, he married painter El ...

, Helen Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler (December 12, 1928 – December 27, 2011) was an American abstract expressionist painter. She was a major contributor to the history of postwar American painting. Having exhibited her work for over six decades (early 1950s u ...

, Philip Guston

Philip Guston (born Phillip Goldstein, June 27, 1913 – June 7, 1980), was a Canadian American painter, printmaker, muralist and draftsman. Early in his five decade career, muralist David Siquieros described him as one of "the most promising ...

, Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns (born May 15, 1930) is an American painter, sculptor, and printmaker whose work is associated with abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, and pop art. He is well known for his depictions of the American flag and other US-related top ...

, Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell (February 12, 1925 – October 30, 1992) was an American artist who worked primarily in painting and printmaking, and also used pastel and made other works on paper. She was an active participant in the New York School of artis ...

, Robert Motherwell

Robert Motherwell (January 24, 1915 – July 16, 1991) was an American abstract expressionist painter, printmaker, and editor of ''The Dada Painters and Poets: an Anthology''. He was one of the youngest of the New York School, which also inc ...

, Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986) was an American modernist artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O'Keeffe has been called the "Mother of Ame ...

, Jackson Pollock

Paul Jackson Pollock (; January 28, 1912August 11, 1956) was an American painter and a major figure in the abstract expressionism, abstract expressionist movement. He was widely noticed for his "Drip painting, drip technique" of pouring or splas ...

, Robert Rauschenberg

Milton Ernest "Robert" Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the Pop art movement. Rauschenberg is well known for his Combines (1954–1964), a group of artwor ...

, Ad Reinhardt, Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn (September 12, 1898 – March 14, 1969) was an American artist. He is best known for his works of social realism, his left-wing political views, and his series of lectures published as ''The Shape of Content''.

Biography

Shahn was bor ...

, and Frank Stella

Frank Philip Stella (born May 12, 1936) is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker, noted for his work in the areas of minimalism and post-painterly abstraction. Stella lives and works in New York City.

Biography

Frank Stella was born in Ma ...

, as well as Northwest painters Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves

Morris Graves (August 28, 1910 – May 5, 2001) was an American painter. He was one of the earliest Modern artists from the Pacific Northwest to achieve national and international acclaim. His style, referred to by some reviewers as Mysticism, ...

, Paul Horiuchi, and Mark Tobey

Mark George Tobey (December 11, 1890 – April 24, 1976) was an American painter. His densely structured compositions, inspired by Asian calligraphy, resemble Abstract expressionism, although the motives for his compositions differ philosophi ...

. American sculptors included Leonard Baskin

Leonard Baskin (August 15, 1922 – June 3, 2000) was an American sculptor, draughtsman and graphic artist, as well as founder of the Gehenna Press (1942–2000). One of America's first fine arts presses, it went on to become "one of the most imp ...

, Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder (; July 22, 1898 – November 11, 1976) was an American sculptor known both for his innovative mobiles (kinetic sculptures powered by motors or air currents) that embrace chance in their aesthetic, his static "stabiles", and hi ...

, Joseph Cornell

Joseph Cornell (December 24, 1903 – December 29, 1972) was an American visual artist and film-maker, one of the pioneers and most celebrated exponents of assemblage. Influenced by the Surrealists, he was also an avant-garde experimental filmm ...

, Louise Nevelson

Louise Nevelson (September 23, 1899 – April 17, 1988) was an American sculptor known for her monumental, monochromatic, wooden wall pieces and outdoor sculptures.

Born in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Kyiv Oblast ...

, Isamu Noguchi

was an American artist and landscape architect whose artistic career spanned six decades, from the 1920s onward. Known for his sculpture and public artworks, Noguchi also designed stage sets for various Martha Graham productions, and severa ...

, and 19 others. The 50 international contemporary artists represented included the likes of painters Fritz Hundertwasser, Joan Miró

Joan Miró i Ferrà ( , , ; 20 April 1893 – 25 December 1983) was a Catalan painter, sculptor and ceramicist born in Barcelona. A museum dedicated to his work, the Fundació Joan Miró, was established in his native city of Barcelona ...

, Antoni Tàpies

Antoni Tàpies i Puig, 1st Marquess of Tápies (; 13 December 1923 – 6 February 2012) was a Catalan People, Catalan painter, sculptor and art theorist, who became one of the most famous European artists of his generation.

Life

The son of Jo ...

, and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, and sculptors Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi-abstract art, abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Mo ...

and Jean Arp

Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp (16 September 1886 – 7 June 1966), better known as Jean Arp in English, was a German-French sculptor, painter, and poet. He was known as a Dadaist and an abstract artist.

Early life

Arp was born in Straßburg (now Stras ...

. In addition, there were exhibitions of Mark Tobey's paintings and of Asian art, drawn from the collections of the Seattle Art Museum; and an additional exhibition of 72 "masterpieces" ranging from Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

, El Greco

Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos ( el, Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος ; 1 October 1541 7 April 1614), most widely known as El Greco ("The Greek"), was a Greek painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. "El ...

, Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio, known as simply Caravaggio (, , ; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the final four years of h ...

, Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally cons ...

, and Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat from the Duchy of Brabant in the Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque traditio ...

through Toulouse-Lautrec

Comte Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901) was a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman, caricaturist and illustrator whose immersion in the colourful and theatrical life of Paris in the l ...

, Monet, and Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for turni ...

to Klee

Paul Klee (; 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented wi ...

, Braque

Georges Braque ( , ; 13 May 1882 – 31 August 1963) was a major 20th-century French painter, collagist, draughtsman, printmaker and sculptor. His most notable contributions were in his alliance with Fauvism from 1905, and the role he playe ...

, and Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, with no shortage of other comparably famous artists represented.

A separate gallery presented Northwest Coast Indian art, and featured a series of large paintings by Bill Holm introducing Northwest Native motifs.

A separate gallery presented Northwest Coast Indian art, and featured a series of large paintings by Bill Holm introducing Northwest Native motifs.

World of Entertainment

A US$15 million performing-arts program at the fair ranged from aboxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

championship to an international twirling

Twirling is a form of object manipulation where an object is twirled by one or two hands, the fingers or by other parts of the body. Twirling practice manipulates the object in circular or near circular patterns. It can also be done indirectly by ...

competition but with no shortage of nationally and internationally famous performers, especially at the new Opera House and Playhouse. After the fair, the Playhouse became the Seattle Repertory Theatre; in the mid-1980s it became the Intiman Playhouse

Intiman Theatre Festival in Seattle, Washington, was founded in 1972 as a resident theatre by Margaret "Megs" Booker, who named it for August Strindberg's Stockholm theater.

. When the Intiman Theatre became financially unstable, Cornish College of the Arts

Cornish College of the Arts (CCA) is a private art college in Seattle, Washington. It was founded in 1914.

History

Cornish College of the Arts was founded in 1914 as the Cornish School of Music, by Nellie Cornish (1876–1956), a teacher of ...

took over the lease from the city of Seattle, and now operates it as the Cornish Playhouse at Seattle Center.

Opera House performances

Scheduled groups performing at the Opera House included: Source:Other performances

Events and performances at the Playhouse included Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre; a chamber music performance by

Events and performances at the Playhouse included Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre; a chamber music performance by Isaac Stern

Isaac Stern (July 21, 1920 – September 22, 2001) was an American violinist.

Born in Poland, Stern came to the US when he was 14 months old. Stern performed both nationally and internationally, notably touring the Soviet Union and China, and ...

, Milton Katims

Milton Katims (June 24, 1909February 27, 2006) was an American violist and conductor. He was music director of the Seattle Symphony for 22 years (1954–76). In that time he added more than 75 works, made recordings, premiered new pieces and le ...

, Leonard Rose, Eugene Istomin

Eugene George Istomin (November 26, 1925October 10, 2003) was an American pianist. He was a winner of the Leventritt Award and recorded extensively as a soloist and in a piano trio in which he collaborated with Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose.

Car ...

, the Claiborne Brothers gospel quartet, and the Juilliard String Quartet; two appearances by newsman Edward R. Murrow

Edward Roscoe Murrow (born Egbert Roscoe Murrow; April 25, 1908 – April 27, 1965) was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broadcasts from Europe f ...

; Bunraku

(also known as ) is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theatre, founded in Osaka in the beginning of the 17th century, which is still performed in the modern day. Three kinds of performers take part in a performance: the or (puppeteers ...

theater; Richard Dyer-Bennet

Richard Dyer-Bennet (6 October 1913 in Leicester, England – 14 December 1991 in Monterey, Massachusetts) was an English-born American folk singer (or his own preferred term, "minstrel"), recording artist, and voice teacher.

Biography

He was bo ...

; Hal Holbrook

Harold Rowe Holbrook Jr. (February 17, 1925 – January 23, 2021) was an American actor, television director, and screenwriter. He first received critical acclaim in 1954 for a one-man stage show that he developed called ''Mark Twain Tonight!'' ...

's solo show as Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

; the Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

and Benny Goodman

Benjamin David Goodman (May 30, 1909 – June 13, 1986) was an American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing".

From 1936 until the mid-1940s, Goodman led one of the most popular swing big bands in the United States. His conc ...

jazz orchestras; Lawrence Welk

Lawrence Welk (March 11, 1903 – May 17, 1992) was an American accordionist, bandleader, and television impresario, who hosted the '' The Lawrence Welk Show'' from 1951 to 1982. His style came to be known as "champagne music" to his radio, te ...

; Nat King Cole

Nathaniel Adams Coles (March 17, 1919 – February 15, 1965), known professionally as Nat King Cole, was an American singer, jazz pianist, and actor. Cole's music career began after he dropped out of school at the age of 15, and continued f ...

; and Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Jane Fitzgerald (April 25, 1917June 15, 1996) was an American jazz singer, sometimes referred to as the "First Lady of Song", "Queen of Jazz", and "Lady Ella". She was noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phrasing, timing, in ...

. Also during the fair, Memorial Stadium hosted the Ringling Brothers Circus

Ringling Bros. World's Greatest Shows is a circus founded in Baraboo, Wisconsin, United States in 1884 by five of the seven Ringling brothers: Albert, August, Otto, Alfred T., Charles, John, and Henry. The Ringling brothers were sons of a Ge ...

, Tommy Bartlett's Water Ski Sky and Stage Show, Roy Rogers

Roy Rogers (born Leonard Franklin Slye; November 5, 1911 – July 6, 1998) was an American singer, actor, and television host. Following early work under his given name, first as co-founder of the Sons of the Pioneers and then acting, the rebra ...

and Dale Evans

Dale Evans Rogers (born Frances Octavia Smith; October 31, 1912 – February 7, 2001) was an American actress, singer, and songwriter. She was the third wife of singing cowboy Roy Rogers.

Early life

Evans was born Frances Octavia Smith on ...

' Western Show, and an appearance by evangelist Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American evangelist and an ordained Southern Baptist minister who became well known internationally in the late 1940s. He was a prominent evangelical Christi ...

.

The fair and the city were the setting of the Elvis Presley

Elvis Aaron Presley (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977), or simply Elvis, was an American singer and actor. Dubbed the " King of Rock and Roll", he is regarded as one of the most significant cultural figures of the 20th century. His ener ...

movie ''It Happened at the World's Fair

''It Happened at the World's Fair'' is a 1963 American musical film starring Elvis Presley as a crop-dusting pilot. It was filmed in Seattle, Washington, site of the Century 21 Exposition. The governor of Washington at the time, Albert Rosellini, ...

'' (1963), with a young Kurt Russell

Kurt Vogel Russell (born March 17, 1951) is an American actor. He began acting on television at the age of 12 in the western series ''The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters'' (1963–1964). In the late 1960s, he signed a ten-year contract with The ...

making his first screen appearance. Location shooting began on September 4 and concluded nearly two weeks later. The film would be released the following spring, long after the fair had ended.

Show Street

At the northeast corner of the grounds (now theKCTS-TV

KCTS-TV (channel 9) is a PBS member television station in Seattle, Washington, United States, owned by Cascade Public Media. Its studios are located at the northeast corner of Seattle Center adjacent to the Space Needle, and its transmitter i ...

studios), Show Street was the "adult entertainment

The sex industry (also called the sex trade) consists of businesses that either directly or indirectly provide sex-related products and services or adult entertainment. The industry includes activities involving direct provision of sex-related ...

" portion of the fair. Attractions included Gracie Hansen's Paradise International (a Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

-style floor show (rivalled next door by LeRoy Prinz's "Backstage USA")), Sid and Marty Krofft

Sid Krofft (born July 30, 1929) and Marty Krofft (born April 9, 1937) are a Canadian sibling team of television creators and puppeteers. Through their production company, Sid & Marty Krofft Pictures, they have made numerous children's television a ...

's adults-only puppet show, '' Les Poupées de Paris'', and (briefly, until it was shut down) a show featuring naked "Girls of the Galaxy".''Official Guide Book'', pp. 110–114. Tamer entertainment came in forms such as the Paris Spectacular wax museum

A wax museum or waxworks usually consists of a collection of wax sculptures representing famous people from history and contemporary personalities exhibited in lifelike poses, wearing real clothes.

Some wax museums have a special section dubb ...

, an elaborate Japanese Village, and the Hawaiian Pavilion.

Other sections of the fair

;Gayway: The Gayway was a small amusement park; after the fair it became the Fun Forest. It included such rides as the Flight to Mars, a dark amusement ride themed around space pirates on Mars, decorated with

;Gayway: The Gayway was a small amusement park; after the fair it became the Fun Forest. It included such rides as the Flight to Mars, a dark amusement ride themed around space pirates on Mars, decorated with black light

A blacklight, also called a UV-A light, Wood's lamp, or ultraviolet light, is a lamp that emits long-wave (UV-A) ultraviolet light and very little visible light. One type of lamp has a violet filter material, either on the bulb or in a sepa ...

s and glow paint. In 2011, the Fun Forest was shut down and the Chihuly Garden and Glass

Chihuly Garden and Glass is an exhibit in the Seattle Center directly next to the Space Needle, showcasing the studio glass of Dale Chihuly. It opened in May 2012 at the former site of the defunct Fun Forest amusement park.

The project feature ...

opened in its place.

;Boulevards of the World: Boulevards of the World was "the shopping center of the fair". It also included the Plaza of the States and the original version of the International Fountain.

;Exhibit Fair: The Exhibit Fair provided another shopping district under the north stands of Memorial Stadium.

;Food and Favors: "Food and Favors", officially one of the "areas" of the fair, simply encompassed the various restaurants, food stands, etc., scattered throughout the grounds. These ranged from vending machines and food stands to the Eye of the Needle (atop the Space Needle) and the private Century 21 Club.

;Food Circus: The Food Circus was a food court

A food court (in Asia-Pacific also called food hall or hawker centre) is generally an indoor plaza or common area within a facility that is contiguous with the counters of multiple food vendors and provides a common area for self-serve dinner. ...

in the former armory, later named the Center House, and renamed the Armory in 2012 as a remodel of the building continues. Unlike the current arrangement with a stage and a large open space for dancing, events, and temporary booths, many food booths were in the middle of the room as well as at the edges. There were 52 concessionaires in all, nine of them with exhibits in addition to their food for sale. Beginning in 1963, the Food Circus also housed a variety of museums, including Jones' Fantastic Show Jones' Fantastic Museum was a family-oriented museum filled with a unique collection of weird and amazing inventions, strange sideshow attractions, old-time dime museum machines and antique exhibits, originally located in Snohomish County, and lat ...

, the Jules Charbneau World of Miniatures, and the Pullen Klondike Museum.

Promotional video

See also

*List of world expositions

The Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) sanctions world expositions. Some have been recognised retrospectively because they took place before the BIE came into existence.

The designation "World Exposition" refers to a class of the largest ...

*List of world's fairs

This is a list of international and colonial world's fairs, as well as a list of national exhibitions, a comprehensive chronological list of world's fairs (with notable permanent buildings built).

1790s

* 1791 – Prague, Bohemia, Habsburg ...

Notes

References

*''Official Guide Book: Seattle World's Fair 1962'', Acme Publications: Seattle (1962)External links

Official website of the BIE

at HistoryLink.

Century 21 – The 1962 Seattle World's Fair

at HistoryLink

Century 21 Digital Collection from the Seattle Public Library

– over 1800 related photos, advertisements, reports, programs, postcards, brochures, and more. *"Seattle Center", p. 18–24 i

Survey Report: Comprehensive Inventory of City-Owned Historic Resources, Seattle, Washington

Department of Neighborhoods (Seattle) Historic Preservation, offers an extremely detailed account of the acquisition of land for the exposition and of past and present buildings on the grounds.

Seattle Photographs Collection, Century 21 Exposition

– University of Washington Digital Collection

Pamphlet and Textual Ephemera Collection, Century 21 Exposition documents

– University of Washington Digital Collection {{Coord, 47, 37, 17, N, 122, 21, 03, W, format=dms, display=title, type:landmark_region:US-WA Seattle Center History of the West Coast of the United States 1962 in Washington (state) 1960s in Seattle Articles containing video clips