History of the Caribbean on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The following year, the first Spanish settlements were established in the Caribbean. Although the Spanish conquests of the

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The following year, the first Spanish settlements were established in the Caribbean. Although the Spanish conquests of the

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the  Between 800 and 200 BCE a new migratory group expanded through the Caribbean island: the Saladoid. This group is named after the Saladero site in

Between 800 and 200 BCE a new migratory group expanded through the Caribbean island: the Saladoid. This group is named after the Saladero site in

Soon after the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the

Soon after the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the

During the first voyage of the explorer Christopher Columbus contact was made with the Lucayans in the

During the first voyage of the explorer Christopher Columbus contact was made with the Lucayans in the

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

French corsair attacks began in the early 1520s, as soon as France declared war on Spain in 1521. At the time, prodigious treasures from Mexico began to cross the Atlantic en route to Spain. French monarch

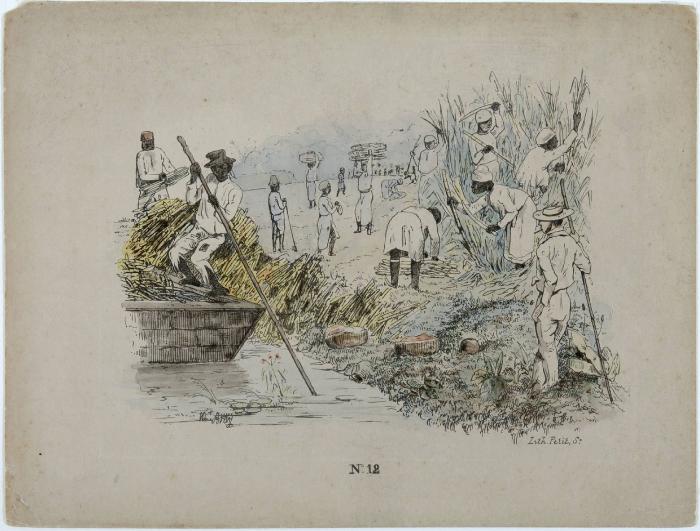

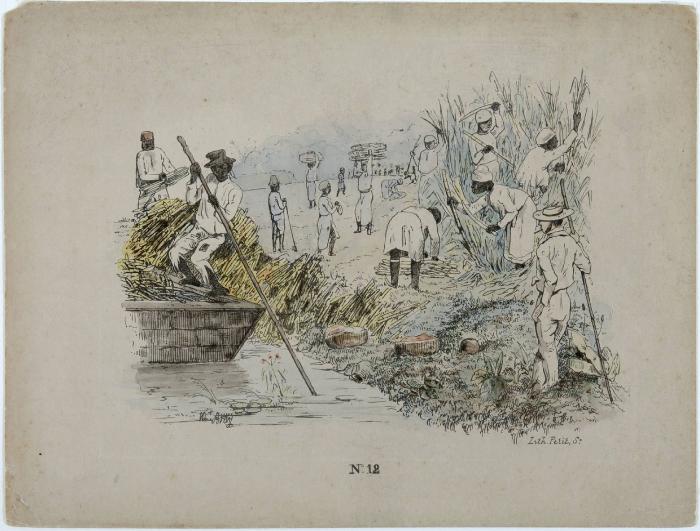

The development of agriculture in the Caribbean required a large workforce of manual labourers, which the Europeans found by taking advantage of the slave trade in Africa. The

The development of agriculture in the Caribbean required a large workforce of manual labourers, which the Europeans found by taking advantage of the slave trade in Africa. The

The New World plantations were established in order to fulfill the growing needs of the Old World. The sugar plantations were built with the intention of exporting the sugar back to Britain which is why the British did not need to stimulate local demand for the sugar with wages. A system of slavery was adapted since it allowed the coloniser to have an abundant work force with little worry about declining demands for sugar. In the 19th century wages were finally introduced with the abolition of slavery. The new system in place however was similar to the previous as it was based on white capital and coloured labour. Large numbers of unskilled workers were hired to perform repeated tasks, which made if very difficult for these workers to ever leave and pursue any non farming employment. Unlike other countries, where there was an urban option for finding work, the Caribbean countries had money invested in agriculture and lacked any core industrial base. The cities that did exist offered limited opportunities to citizens and almost none for the unskilled masses who had worked in agriculture their entire lives. The products produced brought in no profits for the countries since they were sold to the colonial occupant buyer who controlled the price the products were sold at. This resulted in extremely low wages with no potential for growth since the occupant nations had no intention of selling the products at a higher price to themselves.

The result of this economic exploitation was a plantation dependence which saw the Caribbean nations possessing a large quantity of unskilled workers capable of performing agricultural tasks and not much else. After many years of colonial rule the nations also saw no profits brought into their country since the sugar production was controlled by the colonial rulers. This left the Caribbean nations with little capital to invest towards enhancing any future industries unlike European nations which were developing rapidly and separating themselves technologically and economically from most impoverished nations of the world.

The New World plantations were established in order to fulfill the growing needs of the Old World. The sugar plantations were built with the intention of exporting the sugar back to Britain which is why the British did not need to stimulate local demand for the sugar with wages. A system of slavery was adapted since it allowed the coloniser to have an abundant work force with little worry about declining demands for sugar. In the 19th century wages were finally introduced with the abolition of slavery. The new system in place however was similar to the previous as it was based on white capital and coloured labour. Large numbers of unskilled workers were hired to perform repeated tasks, which made if very difficult for these workers to ever leave and pursue any non farming employment. Unlike other countries, where there was an urban option for finding work, the Caribbean countries had money invested in agriculture and lacked any core industrial base. The cities that did exist offered limited opportunities to citizens and almost none for the unskilled masses who had worked in agriculture their entire lives. The products produced brought in no profits for the countries since they were sold to the colonial occupant buyer who controlled the price the products were sold at. This resulted in extremely low wages with no potential for growth since the occupant nations had no intention of selling the products at a higher price to themselves.

The result of this economic exploitation was a plantation dependence which saw the Caribbean nations possessing a large quantity of unskilled workers capable of performing agricultural tasks and not much else. After many years of colonial rule the nations also saw no profits brought into their country since the sugar production was controlled by the colonial rulers. This left the Caribbean nations with little capital to invest towards enhancing any future industries unlike European nations which were developing rapidly and separating themselves technologically and economically from most impoverished nations of the world.

The Caribbean region was war-torn throughout much of colonial history, but the wars were often based in Europe, with only minor battles fought in the Caribbean. Some wars, however, were borne of political turmoil in the Caribbean itself.

*

The Caribbean region was war-torn throughout much of colonial history, but the wars were often based in Europe, with only minor battles fought in the Caribbean. Some wars, however, were borne of political turmoil in the Caribbean itself.

*

The plantation system and the slave trade that enabled its growth led to regular slave resistance in many Caribbean islands throughout the colonial era. Resistance was made by escaping from the plantations altogether, and seeking refuge in the areas free of European settlement. Communities of escaped slaves, who were known as Maroon (people), Maroons, banded together in heavily forested and mountainous areas of the

The plantation system and the slave trade that enabled its growth led to regular slave resistance in many Caribbean islands throughout the colonial era. Resistance was made by escaping from the plantations altogether, and seeking refuge in the areas free of European settlement. Communities of escaped slaves, who were known as Maroon (people), Maroons, banded together in heavily forested and mountainous areas of the

As of the early 21st century, not all Caribbean islands have become independent. Several islands continue to have government ties with European countries, or with the United States.

French overseas departments and territories include several Caribbean islands.

As of the early 21st century, not all Caribbean islands have become independent. Several islands continue to have government ties with European countries, or with the United States.

French overseas departments and territories include several Caribbean islands.

President James Monroe's State of the Union address in 1823 included a significant change to United States foreign policy which later became known as the Monroe Doctrine. In a key addition to this policy called the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States reserved the right to intervene in any nation of the Western Hemisphere it determined to be engaged in "chronic wrongdoing". This new expansionism coupled with the loss of relative power by the colonial nations enabled the United States to become a major influence in the region. In the early part of the twentieth century this influence was extended by participation in

President James Monroe's State of the Union address in 1823 included a significant change to United States foreign policy which later became known as the Monroe Doctrine. In a key addition to this policy called the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States reserved the right to intervene in any nation of the Western Hemisphere it determined to be engaged in "chronic wrongdoing". This new expansionism coupled with the loss of relative power by the colonial nations enabled the United States to become a major influence in the region. In the early part of the twentieth century this influence was extended by participation in

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Caribbean islands enjoyed greater political stability. Large-scale violence was no longer a threat after the end of slavery in the islands. The British-controlled islands in particular benefited from investments in the infrastructure of colonies. By the beginning of World War I, all British-controlled islands had their own police force, fire department, doctors and at least one hospital. Sewage systems and public water supplies were built, and death rates in the islands dropped sharply. Literacy also increased significantly during this period, as schools were set up for students descended from African slaves. Public libraries were established in large towns and capital cities.

These improvements in the quality of life for the inhabitants also made the islands a much more attractive destination for visitors. Tourists began to visit the Caribbean in larger numbers by the beginning of the 20th century, although there was a tourist presence in the region as early as the 1880s. The U.S.-owned

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Caribbean islands enjoyed greater political stability. Large-scale violence was no longer a threat after the end of slavery in the islands. The British-controlled islands in particular benefited from investments in the infrastructure of colonies. By the beginning of World War I, all British-controlled islands had their own police force, fire department, doctors and at least one hospital. Sewage systems and public water supplies were built, and death rates in the islands dropped sharply. Literacy also increased significantly during this period, as schools were set up for students descended from African slaves. Public libraries were established in large towns and capital cities.

These improvements in the quality of life for the inhabitants also made the islands a much more attractive destination for visitors. Tourists began to visit the Caribbean in larger numbers by the beginning of the 20th century, although there was a tourist presence in the region as early as the 1880s. The U.S.-owned

correspondent banking

arrangements by extra-regional banks.

Ports both large and small were built throughout the Caribbean during the colonial era. The export of sugar on a large scale made the Caribbean one of the world's shipping cornerstones, as it remains today. Many key shipping routes still pass through the region.

The development of large-scale shipping to compete with other ports in Central and South America ran into several obstacles during the 20th century.

Ports both large and small were built throughout the Caribbean during the colonial era. The export of sugar on a large scale made the Caribbean one of the world's shipping cornerstones, as it remains today. Many key shipping routes still pass through the region.

The development of large-scale shipping to compete with other ports in Central and South America ran into several obstacles during the 20th century.

online

* Bousquet, Ben and Colin Douglas. ''West Indian Women at War: British Racism in World War II'' (1991

online

* Bush, Barbara. ''Slave Women in Caribbean Society: 1650–1838'' (1990) * Cromwell, Jesse. "More than Slaves and Sugar: Recent Historiography of the Trans-imperial Caribbean and Its Sinew Populations." ''History Compass'' (2014) 12#10 pp 770–783. * * de Kadt, Emanuel (editor), 1972. ''Patterns of foreign influence in the Caribbean'', London, New York, published for the Royal Institute of International Affairs by Oxford University Press. * * Dooley Jr, Edwin L. "Wartime San Juan, Puerto Rico: The Forgotten American Home Front, 1941-1945." ''Journal of Military History'' 63.4 (1999): 921. * Dunn, Richard. ''Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624–1713'' 1972. * Eccles, Karen E. and Debbie McCollin, eds. ''World War II and the Caribbean'' (2017

excerpt

historiography covered in the introduction. * Emmer, Pieter C., ed. ''General History of the Caribbean''. London: UNESCO Publishing 1999. * Floyd, Troy S. ''The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492-1526''. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1973. * Healy, David. ''Drive to hegemony: the United States in the Caribbean, 1898-1917'' (1988). * Higman, Barry W. ''A Concise History of the Caribbean.'' (2011) * Hoffman, Paul E. ''The Spanish Crown and the Defense of the Caribbean, 1535-1585: Precedent, Patrimonialism, and Royal Parsimony''. Baton Rouge: LSU Press 1980. * Jackson, Ashley. ''The British Empire and the Second World War'' (Continuum, 2006). pp 77–95 on Caribbean colonies * Keegan, William F. ''Taíno Myth and Practice: the Arrival of the Stranger King''. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 2007. * Klein, Herbert S. and Ben Vinson, ''African slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean'' Oxford University Press, 2007 * Klooster, Wim, 1998. ''Illicit riches. Dutch trade in the Caribbean, 1648-1795'', KITLV. * Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. ''A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny''. Addison-Wesley Publishing. * Martin, Tony, ''Caribbean History: From Pre-colonial Origins to the Present'' (2011) * * Moya Pons, F. ''History of the Caribbean: Plantations, Trade, and War in the Atlantic World'' (2007) * Palmié, Stephan and Francisco Scarano, eds. ''The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples'' (U of Chicago Press, 2011) 660 pp * Ratekin, Mervyn. "The Early Sugar Industry in Española," ''Hispanic American Historical Review'' 34:2(1954):1-19. * Rogozinski, Jan. ''A Brief History of the Caribbean'' (2000). * Sauer, Carl O. ''The Early Spanish Main''. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1969. * Sheridan, Richard. ''Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775'' (1974) * Stinchcombe, Arthur. ''Sugar Island Slavery in the Age of Enlightenment: The Political Economy of the Caribbean World'' (1995) * Tibesar, Antonine S. "The Franciscan Province of the Holy Cross of Española," ''The Americas'' 13:4(1957):377-389. * Wilson, Samuel M. ''The Indigenous People of the Caribbean''. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1997.

"The History of the Caribby-Islands"

from 1666

Caribbean settlement in Britain

{{Caribbean topics *Caribbean

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The following year, the first Spanish settlements were established in the Caribbean. Although the Spanish conquests of the

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The following year, the first Spanish settlements were established in the Caribbean. Although the Spanish conquests of the Aztec empire

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance ( nci, Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: , , and . These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexi ...

and the Inca empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

in the early sixteenth century made Mexico and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

more desirable places for Spanish exploration and settlement, the Caribbean remained strategically important.

From the 1620s and 1630s onwards, non-Hispanic privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s, traders, and settlers established permanent colonies and trading posts on the Caribbean islands neglected by Spain. Such colonies spread throughout the Caribbean, from the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

in the North West to Tobago

Tobago () is an island and ward within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trinidad and about off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. It also lies to the southeast of Grenada. The offic ...

in the South East. Furthermore, during this period, French and English buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 until about 168 ...

s settled on the island of Tortuga, the northern and western coasts of Hispaniola ( Haiti and Dominican Republic), and later in Jamaica.

After the Spanish American war in 1898, the islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico were no longer part of the Spanish Empire in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

. In the 20th century the Caribbean was again important during World War II, in the decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence ...

wave after the war, and in the tension between Communist Cuba and the United States. Genocide, slavery, immigration, and rivalry between world powers have given Caribbean history an impact disproportionate to its size.

Before European contact

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

the northern part of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

was occupied by groups of small-game hunters, fishers and foragers. These groups occasionally resided in semi-permanent camp sites, while mostly being mobile in order to make use of a wide range of plant and animal resources in a variety of habitats.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

was the first Caribbean island to have been settled as early as 9000/8000 BCE. However, the first settlers most likely arrived in Trinidad when it was still attached to South America by land bridges. It was not until about 7000/6000 BCE, during the early Holocene that Trinidad became an island due to a significant jump in sea level by about 60 m. Climate change may have been a cause for this sea level rise. Hence Trinidad was the only Caribbean Island that could have been colonised by indigenous people from the South American mainland by not traversing hundreds or thousands kilometres of open sea. The earliest major habitation sites discovered in Trinidad are the shell midden deposits of Banwari Trace

Banwari Trace, an Archaic (pre-ceramic) site in southwestern Trinidad, is the oldest archaeological site in the Caribbean. The site has revealed two separate periods of occupation; one between 7200 and 6100 BP (Strata I and II) and the other be ...

and St. John, which have been dated between 6000 and 5100 BCE. Both shell midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and eco ...

s represent extended deposits of discarded shells that originally yielded a food source and stone and bone tools. They are considered to belong to the Ortoiroid

The Ortoiroid people were the second wave of human settlers of the Caribbean who began their migration into the Antilles around 2000 BCE. They were preceded by the Casimiroid peoples (~4190-2165 BCE). They are believed to have originated in the Or ...

archaeological tradition, named after the similar but much more recent Ortoire site in Mayaro, Trinidad.

Classifying Caribbean prehistory into different "ages" has proven a difficult and controversial task. In the 1970s archaeologist Irving Rouse

Benjamin Irving Rouse (August 29, 1913 – February 24, 2006) was an American archaeologist on the faculty of Yale University best known for his work in the Greater and Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean, especially in Haiti. He also conducted field ...

defined three "ages" to classify Caribbean prehistory: the Lithic, Archaic and Ceramic Age, based on archaeological evidence. Current literature on Caribbean prehistory still uses the three aforementioned terms, however, there is much dispute regarding their usefulness and definition. In general, the Lithic Age is considered the first era of human development in the Americas and the period where stone chipping is first practised. The ensuing Archaic age is often defined by specialised subsistence adaptions, combining hunting, fishing, collecting and the managing of wild food plants. Ceramic Age communities manufactured ceramic and made use of small-scale agriculture.

With the exception of Trinidad the first Caribbean islands were settled between 3500 and 3000 BCE, during the Archaic Age. Archaeological sites of this period have been located in Barbados, Cuba, Curaçao and St. Martin, followed closely by Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. This settlement phase is often attributed to the Ortoiroid culture.

Between 800 and 200 BCE a new migratory group expanded through the Caribbean island: the Saladoid. This group is named after the Saladero site in

Between 800 and 200 BCE a new migratory group expanded through the Caribbean island: the Saladoid. This group is named after the Saladero site in Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, where their distinctive pottery (typically distinguished by white-on-red painted designs) was first identified. The introduction of pottery and plant domestication to the Caribbean is often attributed to Saladoid groups and represents the beginning of the Ceramic Age. However, recent studies have revealed that crops and pottery were already present in some Archaic Caribbean populations before the arrival of the Saladoid. Although a large amount of Caribbean Islands were settled during the Archaic and Ceramic Age, some islands were presumably visited much later. For example, Jamaica has no known settlements until around 600 AD while the Cayman Islands show no settlement evidence before European arrival.

Following the colonisation of Trinidad it was originally proposed that Saladoid groups island-hopped their way to Puerto Rico. However, current research tends to move away from this stepping-stone model in favour of the southward route hypothesis. The southward route hypothesis proposes that the northern Antilles were settled directly from South America followed by progressively southward movements into the Lesser Antilles. This hypothesis has been supported by both radiocarbon

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and c ...

dates and seafaring simulations. One initial impetus of movement from the mainland to the northern Antilles may have been the search for high quality materials such as flint. Flinty Bay on Antigua, is one of the best known sources of high quality flint in the Lesser Antilles. The presence of flint from Antigua on many other Caribbean Islands highlights the importance of this material during the Pre-Columbian period.

The period from 650 to 800 AD saw major cultural, socio-political and ritual reformulations, which took place both on the mainland and in many Caribbean islands. The Saladoid interaction sphere disintegrated rapidly. Furthermore, this period is characterised with a change in climate. Centuries of abundant rainfall were replaced by prolonged droughts and increased hurricane frequency. In general the Caribbean population increased and communities changed from residence in a single village to the creation of settlement cluster. Additionally the amount of agriculture on the Caribbean islands increased. Lithic analysis have also show the development of tighter networks between islands during the post-Saladoid period.

The period after 800 AD can be seen as a period of transition in which status differentiation and hierarchically ranked society evolved, which can be identified by a shift from achieved to ascribed leadership. After about 1200 AD this process was interrupted by the absorption of many Caribbean Islands into the socio-political structure of the Greater Antillean society. This process disrupted more-or-less independent lines of development of local communities and marked the beginnings of sociopolitical changes on a much larger scale.

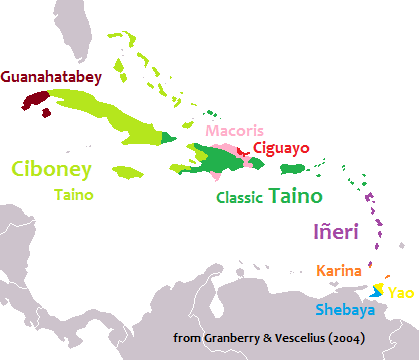

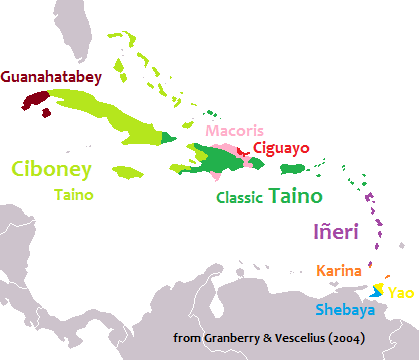

At the time of the European arrival, three major Amerindian indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

lived on the islands: the Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

(sometimes also referred to as Arawak) in the Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, a ...

, the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

and the Leeward Islands; the Kalinago

The Kalinago, also known as the Island Caribs or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated langua ...

and Galibi in the Windward Islands

french: Îles du Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Windward Islands. Clockwise: Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea No ...

; and the Ciboney in western Cuba. The Taínos are subdivided into Classic Taínos, who occupied Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, Western Taínos, who occupied Cuba, Jamaica, and the Bahamian archipelago, and the Eastern Taínos, who occupied the Leeward Islands. Trinidad was inhabited by both Carib speaking and Arawak-speaking groups.

DNA studies changed some of the traditional beliefs about pre-Columbian indigenous history. In 2003 Juan Martinez Cruzado, a geneticist from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez

The University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus (UPRM) or Recinto Universitario de Mayagüez (RUM) in Spanish (also referred to as Colegio and CAAM in allusion to its former name), is a public land-grant university in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. UPRM ...

designed an island-wide DNA survey of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

's people. According to conventional historical belief, Puerto Ricans have mainly Spanish ethnic origins, with some African ancestry, and distant and less significant indigenous ancestry. Cruzado's research revealed that 61% of all Puerto Ricans have Amerindian mitochondrial DNA, 27% have African and 12% Caucasian. According to National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widel ...

, "Among the surprising findings is that most of the Caribbean’s original inhabitants may have been wiped out by South American newcomers a thousand years before the Spanish invasion that began in 1492. Moreover, indigenous populations of islands like Puerto Rico and Hispaniola were likely far smaller at the time of the Spanish arrival than previously thought."

Early colonial history

Soon after the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the

Soon after the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

, both Portuguese and Spanish ships began claiming territories in Central and South America. These colonies brought in gold, and other European powers, most specifically England, the Netherlands, and France, hoped to establish profitable colonies of their own. Imperial rivalries made the Caribbean a contested area during European wars for centuries. In the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

in the early nineteenth century, most of Spanish America broke away from the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, but Cuba and Puerto Rico remained under the Spanish crown until the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

of 1898.

Spanish invasion and subjugation

During the first voyage of the explorer Christopher Columbus contact was made with the Lucayans in the

During the first voyage of the explorer Christopher Columbus contact was made with the Lucayans in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

and the Taíno in Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, and a few of the native people were taken back to Spain. Significant amounts of gold were found in their personal ornaments and other objects such as masks and belts enticing the Spanish search for wealth. To supplement the Amerindian labour, the Spanish imported African slaves. Although Spain claimed the entire Caribbean, they settled only the larger islands of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

(1493), Puerto Rico (1508), Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

(1509), Cuba (1511), and Trinidad (1530) and the small 'pearl islands' of Cubagua and Margarita

A margarita is a cocktail consisting of Tequila, triple sec, and lime juice often served with salt on the rim of the glass. The drink is served shaken with ice (on the rocks), blended with ice (frozen margarita), or without ice (straight u ...

off the Venezuelan coast because of their valuable pearl beds, which were worked extensively between 1508 and 1530.

Other European powers

The other European powers established a presence in the Caribbean after theSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

declined, partly due to the reduced native population of the area from European diseases. The Dutch, the French, and the British followed one another to the region and established a long-term presence. They brought with them millions of slaves kidnapped from Africa to support the tropical plantation system that spread through the Caribbean islands.

* Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 ...

was an English privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

who attacked many Spanish settlements. His most celebrated Caribbean exploit was the capture of the Spanish Silver Train at Nombre de Dios in March, 1573.

* British colonisation of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

began in 1612. British West Indian colonisation began with Saint Kitts in 1623 and Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estima ...

in 1627. The former was used as a base for British colonisation of neighbouring Nevis (1628), Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

(1632), Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with roughly of coastline. It is n ...

(1632), Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The terr ...

(1650) and Tortola (1672).

* French colonisation too began on St. Kitts, the British and the French splitting the island amongst themselves in 1625. It was used as a base to colonise the much larger Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands— Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and ...

(1635) and Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

(1635), St. Martin (1648), St Barts (1648), and St Croix

Saint Croix; nl, Sint-Kruis; french: link=no, Sainte-Croix; Danish and no, Sankt Croix, Taino: ''Ay Ay'' ( ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincorp ...

(1650), but was lost completely to Britain in 1713. From Martinique the French colonised St. Lucia (1643), Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pet ...

(1649), Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographical ...

(1715), and St. Vincent

Saint Vincent may refer to:

People Saints

* Vincent of Saragossa (died 304), a.k.a. Vincent the Deacon, deacon and martyr

* Saint Vincenca, 3rd century Roman martyress, whose relics are in Blato, Croatia

* Vincent, Orontius, and Victor (died 305) ...

(1719).

* The English admiral William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

seized Jamaica in 1655 and it remained under British rule for over 300 years.

* Piracy in the Caribbean

]The era of piracy in the Caribbean began in the 1500s and phased out in the 1830s after the navies of the nations of Western Europe and North America with colonies in the Caribbean began combating pirates. The period during which pirates were ...

was widespread during the early colonial era, especially between 1640 and 1680. The term "buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 until about 168 ...

" is often used to describe a pirate operating in this region.

* In 1625 French buccaneers established a settlement on Tortuga (Haiti), Tortuga, just to the north of Hispaniola, that the Spanish were never able to permanently destroy despite several attempts. The settlement on Tortuga was officially established in 1659 under the commission of King Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

. In 1670 Cap François (later Cap Français, now Cap-Haïtien) was established on the mainland of Hispaniola. Under the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain officially ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France.

* The Dutch took over Saba, Saint Martin, Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius (, ), also known locally as Statia (), is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially "public body") of the Netherlands.

The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, sout ...

, Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coa ...

, Bonaire

Bonaire (; , ; pap, Boneiru, , almost pronounced ) is a Dutch island in the Leeward Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. Its capital is the port of Kralendijk, on the west ( leeward) coast of the island. Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao form the ABC ...

, Aruba

Aruba ( , , ), officially the Country of Aruba ( nl, Land Aruba; pap, Pais Aruba) is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands physically located in the mid-south of the Caribbean Sea, about north of the Venezuela peninsula of P ...

, Tobago, St. Croix, Tortola, Anegada, Virgin Gorda, Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The terr ...

and a short time Puerto Rico, together called the Dutch West Indies, in the 17th century.

* Denmark-Norway first ruled part, then all of the present U.S. Virgin Islands since 1672, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

sold sovereignty over the Danish West Indies in 1917 to the United States, which they are still a part of.

Huguenot corsairs

During the first three-quarters of the sixteenth century, matters of balance of power and dynastic succession weighed heavily on the course of European diplomacy and war. Europe's largest and most powerful kingdoms, France and Spain, were the continent's staunchest rivals. Tensions increased after 1516, when the kingdoms of Castile, León, andAragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

were formally unified under Charles I of Spain, who three years later expanded his domains after his election as Holy Roman Emperor and began to surround France. In 1521, France went to war with the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Spanish troops routed French armies in France, the Italian Peninsula, and elsewhere, forcing the French Crown to surrender in 1526 and again in 1529. The Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

, as the French-Spanish wars came to be known, reignited in 1536 and again in 1542. Intermittent warring between the Valois monarchy and the Habsburg Empire continued until 1559. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

French corsair attacks began in the early 1520s, as soon as France declared war on Spain in 1521. At the time, prodigious treasures from Mexico began to cross the Atlantic en route to Spain. French monarch

Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

challenged Spain's exclusivist claims to the New World and its wealth, demanding to see "the clause in Adam’s will which excluded me from my share when the world was being divided." Giovanni da Verrazzano (aka Jean Florin) led the first recorded French corsair attack against Spanish vessels carrying treasures from the New World. In 1523, off the Cape of St. Vincent, Portugal, his vessels captured two Spanish ships laden with a fabulous treasure consisting of 70,000 ducats worth of gold, large quantities of silver and pearls, and 25,000 pounds of sugar, a much-treasured commodity at the time.

The first recorded incursion in the Caribbean happened in 1528, when a lone French corsair vessel appeared off the coast of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

and its crew sacked the village of San Germán on the western coast of Puerto Rico. In the mid-1530s, corsairs, some Catholic but most of them Protestant (Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

), began routinely attacking Spanish vessels and raiding Caribbean ports and coastal towns; the most coveted were Santo Domingo, Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

, and San Germán. Corsair port raids in Cuba and elsewhere in the region usually followed the rescate (ransom) model, whereby the aggressors seized villages and cities, kidnapped local residents, and demanded payment for their release. If there were no hostages, corsairs demanded ransoms in exchange for sparing towns from destruction. Whether ransoms were paid or not, corsairs looted, committed unspeakable violence against their victims, desecrated churches and holy images, and left smoldering reminders of their incursions.

In 1536, France and Spain went to war again and French corsairs launched a series of attacks on Spanish Caribbean settlements and ships. The next year, a corsair vessel appeared in Havana and demanded a 700-ducat rescate. Spanish men-of-war arrived soon and scared off the intruding vessel, which returned soon thereafter to demand yet another rescate. Santiago was also victim of an attack that year, and both cities endured raids yet again in 1538. The waters off Cuba's northwest became particularly attractive to pirates as commercial vessels returning to Spain had to squeeze through the 90-mile-long strait between Key West and Havana. In 1537–1538, corsairs captured and sacked nine Spanish vessels. While France and Spain were at peace until 1542, beyond-the-line corsair activity continued. When war erupted again, it echoed once more in the Caribbean. A particularly vicious French corsair attack took place in Havana in 1543. It left a gory toll of 200 killed Spanish settlers. In all, between 1535 and 1563, French corsairs carried out around sixty attacks against Spanish settlements and captured over seventeen Spanish vessels in the region (1536–1547).

European wars of religion

While the French and Spanish fought one another in Europe and the Caribbean,England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

sided with Spain, largely because of dynastic alliances. Spain's relations with England soured upon the crowning of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

in 1558. She openly supported the Dutch insurrection and aided Huguenot forces in France. After decades of increasing tensions and confrontations in the northern Atlantic and the Caribbean, Anglo-Spanish hostilities broke out in 1585, when the English Crown dispatched over 7,000 troops to the Netherlands and Queen Elizabeth liberally granted licenses for privateers to carry out piracy against Spain's Caribbean possessions and vessels. Tensions further intensified in 1587, when Elizabeth I ordered the execution of Catholic Mary Queen of Scots after twenty years of captivity and gave the order for a preemptive attack against the Spanish Armada stationed in Cadiz. In retaliation, Spain organised the famous naval attack that ended tragically for Spain with the destruction of the "invincible" Armada in 1588. Spain rebuilt its naval forces, largely with galleons built in Havana, and continued to fight England until Elizabeth's death in 1603. Spain, however, had received a near-fatal blow that ended its standing as Europe's most powerful nation and virtually undisputed master of the Indies.

Following the Franco-Spanish peace treaty of 1559, crown-sanctioned French corsair activities subsided, but piratical Huguenot incursions persisted and in at least one instance led to the formation of a temporary Huguenot settlement in the Isle of Pines, off Cuba. English piracy increased during the reign of Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1625–1649) and became more aggressive as Anglo-Spanish relations tensed up further during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

. Although Spain and the Netherlands had been at war since the 1560s, the Dutch were latecomers, appearing in the region only after the mid-1590s, when the Dutch Republic was no longer on the defensive in its long conflict against Spain. Dutch privateering became more widespread and violent beginning in the 1620s.

English incursions in the Spanish-claimed Caribbean boomed during Queen Elizabeth's rule. These actions originally took the guise of well-organised, large-scale smuggling expeditions headed by piratical smugglers the likes of John Hawkins

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, John Oxenham

John Oxenham ( "John Oxnam", died ) was the first non-Spanish European explorer to cross the Isthmus of Panama in 1575, climbing the coastal cordillera to get to the Pacific Ocean, then referred to by the Spanish as the ''Mar del Sur'' ('Southern ...

, and Francis Drake; their primary objectives were smuggling African slaves into Spain's Caribbean possessions in exchange for tropical products. The first instances of English mercantile piracy took place in 1562–63, when Hawkins’ men raided a Portuguese vessel off the coast of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, captured the 300 slaves on board, and smuggled them into Santo Domingo in exchange for sugar, hides, and precious woods. Hawkins and his contemporaries mastered the devilish art of maximising the number of slaves that could fit into a ship. He and other slave traders methodically packed slaves by having them lay on their sides, spooned against one another. Such was the case of the slave-trading vessel bearing the sub-lime name Jesus of Lübeck, into whose pestilent bowels, in partnership with Elizabeth I, Hawkins jammed 400 African slaves. In 1567 and 1568, Hawkins commanded two piratical smuggling expeditions, the last of which ended disastrously; he lost almost all of his ships and three-fourths of his men were killed by Spanish soldiers at San Juan de Ulúa

San Juan de Ulúa, also known as Castle of San Juan de Ulúa, is a large complex of fortresses, prisons and one former palace on an island of the same name in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the seaport of Veracruz, Mexico. Juan de Grijalva ...

, off the coast of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, the point of departure of the fleet of New Spain. Hawkins and Drake barely escaped but Oxenham was captured, convicted of heresy by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

and burned alive.

Many of the battles of the Anglo-Spanish war were fought in the Caribbean, not by regular English troops but rather by privateers whom Queen Elizabeth had licensed to carry out attacks on Spanish vessels and ports. These were former pirates who now held a more venerable status as privateers. During those years, over seventy-five documented English privateering expeditions targeted Spanish possessions and vessels. Drake terrorised Spanish vessels and ports. Early in 1586, his forces seized Santo Domingo, retaining control over it for around a month. Before departing they plundered and destroyed the city, taking a huge bounty. Drake's men destroyed church images and ornaments and even erected a defensive palisade with wooden images of saints in the hope that the Spanish soldiers’ Catholic fervor would keep them from firing saints as human shields of sorts.

Enslavement

The development of agriculture in the Caribbean required a large workforce of manual labourers, which the Europeans found by taking advantage of the slave trade in Africa. The

The development of agriculture in the Caribbean required a large workforce of manual labourers, which the Europeans found by taking advantage of the slave trade in Africa. The Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

brought African slaves to British, Dutch, French, Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas, including the Caribbean. Slaves were brought to the Caribbean from the early 16th century until the end of the 19th century. The majority of slaves were brought to the Caribbean colonies between 1701 and 1810. Also in 1816 there was a slave revolution in the colony of Barbados.

The following table lists the number of slaves brought into some of the Caribbean colonies:

Abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

in the Americas and in Europe became vocal opponents of the slave trade throughout the 19th century. The importation of slaves to the colonies was often outlawed years before the end of the institution of slavery itself. It was well into the 19th century before many slaves in the Caribbean were legally free. The trade in slaves was abolished in the British Empire through the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. Men, women and children who were already enslaved in the British Empire remained slaves, however, until Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. When the Slavery Abolition Act came into force in 1834, roughly 700,000 slaves in the British West Indies immediately became free; other enslaved workers were freed several years later after a period of forced apprenticeship. Slavery was abolished in the Dutch Empire in 1814. Spain abolished slavery in its empire in 1811, with the exceptions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Santo Domingo; Spain ended the slave trade to these colonies in 1817, after being paid £400,000 by Britain. Slavery itself was not abolished in Cuba until 1886. France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848.

Marriage, separation, and sale together

"The official plantocratic view of slave marriage sought to deny the slaves any loving bonds or long-standing relationships, thus conveniently rationalising the indiscriminate separation of close kin through sales." "From the earliest days of slavery, indiscriminate sales and separation severely disrupted the domestic life of individual slaves."Bush (1990), ''Slave Women in Caribbean Society'', p. 108. Slaves could be sold so that spouses could be sold separately. "Slave couples were sometimes separated by sale .... They lived as single slaves or as part of maternal or extended families but considered themselves 'married. Sale ofestates

Estate or The Estate may refer to:

Law

* Estate (law), a term in common law for a person's property, entitlements and obligations

* Estates of the realm, a broad social category in the histories of certain countries.

** The Estates, representati ...

with "stock" to pay debts, more common in the late period of slavery, was criticised as separating slave spouses. William Beckford argued for "families to be sold together or kept as near as possible in the same neighbourhood" and "laws were passed in the late period of slavery to prevent the breakup of slave families by sale, ... utthese laws were frequently ignored". "Slaves frequently reacted strongly to enforced severance of their emotional bonds", feeling "sorrow and despair", sometimes, according to Thomas Cooper in 1820, resulting in death from distress.Bush (1990), ''Slave Women in Caribbean Society'', p. 109. John Stewart argued against separation as leading slave buyers to regret it because of utter or period to their lives. Separated slaves often used free time to travel long distances to reunite for a night and sometimes runaway slaves were married couples. However, "sale of slaves and the resulting breakup of families decreased as slave plantations lost prosperity."

Colonial laws

European plantations required laws to regulate the plantation system and the many slaves imported to work on the plantations. This legal control was the most oppressive for slaves inhabiting colonies where they outnumbered their European masters and where rebellion was persistent such asJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

. During the early colonial period, rebellious slaves were harshly punished, with sentences including death by torture; less serious crimes such as assault, theft, or persistent escape attempts were commonly punished with mutilations, such as the cutting off of a hand or a foot.

Under British rule, slaves could only be freed with the consent of their master, and therefore freedom for slaves was rare. British colonies were able to establish laws through their own legislatures, and the assent of the local island governor and the Crown. British law considered slaves to be property, and thus did not recognise marriage for slaves, family rights, education for slaves, or the right to religious practices such as holidays. British law denied all rights to freed slaves, with the exception of the right to a jury trial. Otherwise, freed slaves had no right to own property, vote or hold office, or even enter some trades.

The French Empire regulated slaves under the ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

'' (Black Code) which was in force throughout the empire, but which was based upon French practices in the Caribbean colonies. French law recognized slave marriages, but only with the consent of the master. French law, like Spanish law, gave legal recognition to marriages between European men and black or Creole women. French and Spanish laws were also significantly more lenient than British law in recognising manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

, or the ability of a slave to purchase their freedom and become a "freeman". Under French law, free slaves gained full rights to citizenship. The French also extended limited legal rights to slaves, for example the right to own property, and the right to enter contracts.

Impact of colonialism on the Caribbean

Economic exploitation

The exploitation of theCaribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

landscape dates back to the Spanish conquistadors starting in the 1490s, who forced indigenous peoples held by Spanish settlers in encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

to mine for gold. The more significant development came when Christopher Columbus wrote back to Spain that the islands were made for sugar development.Cross, Malcolm (1979), ''Urbanization and Urban Growth in the Caribbean'', New York: Cambridge University Press. The history of Caribbean agricultural dependency is closely linked with European colonialism which altered the financial potential of the region by introducing a plantation system. Much like the Spanish exploited indigenous labour to mine gold, the 17th century brought a new series of oppressors in the form of the Dutch, the English, and the French. By the middle of the 18th century sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

was Britain's largest import which made the Caribbean that much more important as a colony.

Sugar was a luxury in Europe prior to the 18th century. It became widely popular in the 18th century, then graduated to becoming a necessity in the 19th century. This evolution of taste and demand for sugar as an essential food ingredient unleashed major economic and social changes. Caribbean islands with plentiful sunshine, abundant rainfalls and no extended frosts were well suited for sugarcane agriculture and sugar factories.

Following the emancipation of slaves in 1833 in the United Kingdom, many liberated Africans left their former masters. This created an economic chaos for British owners of Caribbean sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

plantations. The hard work in hot, humid farms required a regular, docile and low-waged labour force. The British looked for cheap labour. This they found initially in China and then mostly in India. The British crafted a new legal system of forced labour, which in many ways resembled enslavement. Instead of calling them slaves, they were called indentured labour. Indians and southeast Asians began to replace Africans previously brought as slaves, under this indentured labour scheme to serve on sugarcane plantations across the British empire. The first ships carrying indentured labourers for sugarcane plantations left India in 1836. Over the next 70 years, numerous more ships brought indentured labourers to the Caribbean, as cheap and docile labour for harsh inhumane work. The slave labour and indentured labour - both in millions of people - were brought into Caribbean, as in other European colonies throughout the world.

The New World plantations were established in order to fulfill the growing needs of the Old World. The sugar plantations were built with the intention of exporting the sugar back to Britain which is why the British did not need to stimulate local demand for the sugar with wages. A system of slavery was adapted since it allowed the coloniser to have an abundant work force with little worry about declining demands for sugar. In the 19th century wages were finally introduced with the abolition of slavery. The new system in place however was similar to the previous as it was based on white capital and coloured labour. Large numbers of unskilled workers were hired to perform repeated tasks, which made if very difficult for these workers to ever leave and pursue any non farming employment. Unlike other countries, where there was an urban option for finding work, the Caribbean countries had money invested in agriculture and lacked any core industrial base. The cities that did exist offered limited opportunities to citizens and almost none for the unskilled masses who had worked in agriculture their entire lives. The products produced brought in no profits for the countries since they were sold to the colonial occupant buyer who controlled the price the products were sold at. This resulted in extremely low wages with no potential for growth since the occupant nations had no intention of selling the products at a higher price to themselves.

The result of this economic exploitation was a plantation dependence which saw the Caribbean nations possessing a large quantity of unskilled workers capable of performing agricultural tasks and not much else. After many years of colonial rule the nations also saw no profits brought into their country since the sugar production was controlled by the colonial rulers. This left the Caribbean nations with little capital to invest towards enhancing any future industries unlike European nations which were developing rapidly and separating themselves technologically and economically from most impoverished nations of the world.

The New World plantations were established in order to fulfill the growing needs of the Old World. The sugar plantations were built with the intention of exporting the sugar back to Britain which is why the British did not need to stimulate local demand for the sugar with wages. A system of slavery was adapted since it allowed the coloniser to have an abundant work force with little worry about declining demands for sugar. In the 19th century wages were finally introduced with the abolition of slavery. The new system in place however was similar to the previous as it was based on white capital and coloured labour. Large numbers of unskilled workers were hired to perform repeated tasks, which made if very difficult for these workers to ever leave and pursue any non farming employment. Unlike other countries, where there was an urban option for finding work, the Caribbean countries had money invested in agriculture and lacked any core industrial base. The cities that did exist offered limited opportunities to citizens and almost none for the unskilled masses who had worked in agriculture their entire lives. The products produced brought in no profits for the countries since they were sold to the colonial occupant buyer who controlled the price the products were sold at. This resulted in extremely low wages with no potential for growth since the occupant nations had no intention of selling the products at a higher price to themselves.

The result of this economic exploitation was a plantation dependence which saw the Caribbean nations possessing a large quantity of unskilled workers capable of performing agricultural tasks and not much else. After many years of colonial rule the nations also saw no profits brought into their country since the sugar production was controlled by the colonial rulers. This left the Caribbean nations with little capital to invest towards enhancing any future industries unlike European nations which were developing rapidly and separating themselves technologically and economically from most impoverished nations of the world.

Wars

The Caribbean region was war-torn throughout much of colonial history, but the wars were often based in Europe, with only minor battles fought in the Caribbean. Some wars, however, were borne of political turmoil in the Caribbean itself.

*

The Caribbean region was war-torn throughout much of colonial history, but the wars were often based in Europe, with only minor battles fought in the Caribbean. Some wars, however, were borne of political turmoil in the Caribbean itself.

* Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

between the Netherlands and Spain.

* The First, Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ea ...

, and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars were battles for supremacy.

* Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between Kingdom of France, France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by t ...

between the European powers.

* The War of Spanish Succession (European name) or Queen Anne's War (American name) spawned a generation of some of the most infamous pirates.

* The War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

(American name) or The War of Austrian Succession (European name) Spain and Britain fought over trade rights; Britain invaded Spanish Florida and attacked the citadel of Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

in present-day Colombia.

* The Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

(European name) or the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

(American name) was the first "world war" between France, her ally Spain, and Britain; France was defeated and was willing to give up all of Canada to keep a few highly profitable sugar-growing islands in the Caribbean. Britain seized Havana toward the end, and traded that single city for all of Florida at the Treaty of Paris in 1763. In addition France ceded Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pet ...

, Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographical ...

, and Saint Vincent (island)

Saint Vincent is a volcanic island in the Caribbean. It is the largest island of the country Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and is located in the Caribbean Sea, between Saint Lucia and Grenada. It is composed of partially submerged volcani ...

to Britain.

* The American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

saw large British and French fleets battling in the Caribbean again. American independence was assured by French naval victories in the Caribbean, but all the British islands that were captured by the French were returned to Britain at the end of the war.

* The French Revolutionary War

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

enabled the creation of the newly independent Republic of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

. In addition, in the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

in 1802, Spain ceded Trinidad to Britain.

* Following the end of the Napoleonic War in 1814 France ceded Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Ameri ...

to Britain.

* The Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

ended Spanish control of Cuba (which soon became independent) and Puerto Rico (which became a US colony), and heralded the period of American dominance of the islands.

Piracy in the Caribbean

]The era of piracy in the Caribbean began in the 1500s and phased out in the 1830s after the navies of the nations of Western Europe and North America with colonies in the Caribbean began combating pirates. The period during which pirates were ...