History of Cleveland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The written history of Cleveland began with the city's founding by General Moses Cleaveland of the Connecticut Land Company on July 22, 1796. Its central location on the southern shore of

The written history of Cleveland began with the city's founding by General Moses Cleaveland of the Connecticut Land Company on July 22, 1796. Its central location on the southern shore of

At the end of the Last Glacial Period, which ended about 15,000 years ago at the southern edge of

At the end of the Last Glacial Period, which ended about 15,000 years ago at the southern edge of

As one of thirty-six founders of the Connecticut Land Company, General Moses Cleaveland was selected as one of its seven directors and was subsequently sent out as the company's agent to map and survey the company's holdings. On July 22, 1796, Cleaveland and his surveyors arrived at the mouth of the

As one of thirty-six founders of the Connecticut Land Company, General Moses Cleaveland was selected as one of its seven directors and was subsequently sent out as the company's agent to map and survey the company's holdings. On July 22, 1796, Cleaveland and his surveyors arrived at the mouth of the

Strongly influenced by its New England roots, Cleveland was home to a vocal group of

Strongly influenced by its New England roots, Cleveland was home to a vocal group of

The Civil War vaulted Cleveland into the first rank of American

The Civil War vaulted Cleveland into the first rank of American

On December 7, 1941,

On December 7, 1941,

Ralph S. Locher became Celebrezze's successor in 1962. Although Locher made some strides, such as expanding Hopkins Airport, his tenure was strained by new challenges facing the city. By the 1960s, Cleveland's economy began to slow down, and residents increasingly sought new housing in the suburbs, reflecting the national trends of

Ralph S. Locher became Celebrezze's successor in 1962. Although Locher made some strides, such as expanding Hopkins Airport, his tenure was strained by new challenges facing the city. By the 1960s, Cleveland's economy began to slow down, and residents increasingly sought new housing in the suburbs, reflecting the national trends of  In 1977, Perk lost the nonpartisan mayoral primary.

In 1977, Perk lost the nonpartisan mayoral primary.

By the beginning of the 1980s, several factors, including changes in international

By the beginning of the 1980s, several factors, including changes in international  In 2002, White was succeeded by

In 2002, White was succeeded by

online

* * Bender, Kim K. "Cleveland, a leader among cities: The municipal home rule movement of the Progressive Era, 1900-1915" (PhD dissertation, University of Oklahoma; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. 9623672). * Bionaz, Robert Emery. "Streetcar city: Popular politics and the shaping of urban progressivism in Cleveland, 1880–1910" (PhD dissertation, University of Iowa; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2002. 3050774). * Borchert, James, and Susan Borchert. "Downtown, Uptown, Out of Town: Diverging Patterns of Upper-Class Residential Landscapes in Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, 1885-1935." ''Social Science History'' 26#2 (2002): 311–346. * Briggs, Robert L. "The Progressive Era In Cleveland, Ohio: Tom L. Johnson's Administration, 1901-1909" (PhD dissertation, University of Chicago; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1962. T-09573). * * * * DeMatteo, Arthur Edward. "Urban reform, politics, and the working class: Detroit, Toledo, and Cleveland, 1890-1922" (PhD dissertation, University of Akron; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1999. 9940602). * * * Hoffman, Mark C. "City republic, civil religion, and the single tax: The progressive-era founding of public administration in Cleveland, 1901-1915" (PhD dissertation, Cleveland State University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1998. 9928627). * Hoffman, Naphtali. "The Process of Economic Development in Cleveland, 1825-1920" (PhD dissertation, Case Western Reserve University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1981. 8109590). * Hothem, Seth, et al. "From Flames to Fish: Resurrection of the Cuyahoga." ''Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation'' 2009.16 (2009): 1655–1672. * Jenkins, William D. "Before Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, and Urban Renewal, 1949-1958." ''Journal of Urban History'' 27.4 (2001): 471–496. * * * Keating, Dennis, Norman Krumholz, and Ann Marie Wieland. "Cleveland's Lakefront: Its Development and Planning." ''Journal of Planning History'' 4#2 (2005): 129–154. * Kukral, Michael A. "Czech Settlements in 19th Century Cleveland, Ohio." ''East European Quarterly'' 38.4 (2004): 473. * * Lamoreaux, Naomi R., Margaret Levenstein, and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. "Financing invention during the second industrial revolution: Cleveland, Ohio, 1870-1920." (No. w10923. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004)

online

* Lee, Darry Kyong Ho. "From a puritan city to a cosmopolitan city: Cleveland Protestants in the changing social order, 1898-1940" (PhD dissertation, Case Western Reserve University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1994. 9501996). * * * Moore, Leonard Nathaniel. "The limits of black power: Carl B. Stokes and Cleveland's African-American community, 1945-1971" (PhD dissertation, The Ohio State University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1998. 9834036). * * Phillips, Julieanne Appleson. " 'Unity in diversity'? The Federation of Women's Clubs and the middle class in Cleveland, Ohio, 1902-1962" (PhD dissertation, Case Western Reserve University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. 9720443). * Poluse, Martin Frank. "Archbishop Joseph Schrembs and the twentieth century Catholic Church in Cleveland, 1921-1945" (PhD dissertation, Kent State University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1991. 92146740. * Rainey, David M. "A Seemingly Insurmountable Problem: Carl Stokes and the Failure of Cleveland Now!" )PhD disssertation, U of Massachusetts Boston; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018. 13419673). * * Suman, Michael Wesley. "The radical urban politics of the Progressive Era: An analysis of the political transformation in Cleveland, Ohio, 1875-1909" (PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1992. 9301960). * Tuennerman-Kaplan, Laura. ''Helping others, helping ourselves: Power, giving, and community identity in Cleveland, Ohio, 1880-1930'' (Kent State University Press, 2001). * Van Tassel, David, and John Grabowski, eds. ''Cleveland: A Tradition of Reforms'' (1986) tten essays by experts * Veronesi, Gene P. ''Italian-Americans & Their Communities of Cleveland'' (1977

online

* * *

Cleveland Historical

at

Cleveland Memory Project

at Cleveland State University

Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery

at the

The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

at

Western Reserve Historical Society

{{Cleveland

The written history of Cleveland began with the city's founding by General Moses Cleaveland of the Connecticut Land Company on July 22, 1796. Its central location on the southern shore of

The written history of Cleveland began with the city's founding by General Moses Cleaveland of the Connecticut Land Company on July 22, 1796. Its central location on the southern shore of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

and the mouth of the Cuyahoga River

The Cuyahoga River ( , or ) is a river located in Northeast Ohio that bisects the City of Cleveland and feeds into Lake Erie.

As Cleveland emerged as a major manufacturing center, the river became heavily affected by industrial pollution, so m ...

allowed it to become a major center for Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

trade in northern Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

in the early 19th century. An important Northern city during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

grew into a major industrial metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural center for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big c ...

and a gateway for European and Middle Eastern

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europea ...

immigrants, as well as African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

migrants, seeking jobs and opportunity.

For most of the 20th century, Cleveland was one of America's largest cities, but after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, it suffered from post-war deindustrialization

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interp ...

and suburbanization

Suburbanization is a population shift from central urban areas into suburbs, resulting in the formation of (sub)urban sprawl. As a consequence of the movement of households and businesses out of the city centers, low-density, peripheral urba ...

. The city has pursued a gradual recovery since the 1980s, becoming a major national center for healthcare and the arts by the early 21st century.

Prehistory

At the end of the Last Glacial Period, which ended about 15,000 years ago at the southern edge of

At the end of the Last Glacial Period, which ended about 15,000 years ago at the southern edge of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

, there was a tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

landscape. It took about two and a half millennia to turn this wet and cold landscape drier and warmer, so that caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

, moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

, deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the re ...

, wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly un ...

, bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the No ...

s and cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large cat native to the Americas. Its range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere. ...

s were prevalent.

The oldest human, paleo-Indian traces reach back as far as 10500 BC. There was an early settlement in Medina County, dated between 9200 and 8850 BC. Some tools consisted of flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

from Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

.

Rising temperatures at about 7500 BC led to a stable phase between 7000 and 4500 BC which had similar characteristics to today's climate. Population grew, and these members of the so-called Early Archaic Culture lived in large families along the rivers and the shores of the lakes. During the warm seasons they met for hunting and gathering. The technology of tools improved but flint was still an important resource in that regard. Important archaeological sites are old Lake Abraham bog as well as sites on Big Creek, Cahoon, Mill and Tinker's Creek. There was a larger settlement where Hilliard Boulevard crosses the Rocky River Rocky River may refer to:

Localities

* Rocky River, Ohio, USA

* Rocky River, New South Wales near Uralla, Australia

Electorates

*Electoral district of Rocky River (South Australia)

Streams

In Australia:

* Rocky River (New South Wales)

* ...

.

Population density further increased during the Middle Archaic period (4500-2000 BC). Ground and polished stone tools and ornaments, and a variety of specialized chipped-stone notched points and knives, scrapers and drills were found on sites at Cuyahoga, Rocky River, Chippewa Creek, Tinker's, and Griswold Creek.

The Late Archaic period (2000 to 500 BC) coincided with a much warmer climate than today. For the first time evidence for regionally specific territories occurs, as well as limited gardening of squash, which later became very important. A long-distance trade of raw materials and finished artifacts with coastal areas, objects which were used in ceremonies and burials. The largest graveyard known is at the junction of the East and West branches of the Rocky River. Differences in status are revealed by the objects which accompanied the dead, like zoo- and anthropomorphic objects or atlatl

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or ''atlatl'' (pronounced or ; Nahuatl ''ahtlatl'' ) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store ene ...

s.

The following Early Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

(500 BC – AD 100) and Middle Woodland (AD 100 – 700) is a period of increased ceremonial exchange and sophisticated rituals. Crude but elaborately decorated pottery appears. Squash becomes more important, maize occurs for ritual procedures. The first Mounds were erected, buildings for which Ohio is world-famous. The mound at Eagle St. Cemetery belongs to the Adena culture

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 500 BCE to 100 CE, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing ...

. Further mounds were found in the east of Tinker's Creek. Horticulture becomes even more important, the same with maize. The huge mounds concentrate much more in southern Ohio

Appalachian Ohio is a bioregion and political unit in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Ohio, characterized by the western foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and the Appalachian Plateau. The Appalachian Regional Commission defines ...

, but they were also found in northern Summit County. Some Hopewellian projectile points, flint-blade knives, and ceramics were found in the area of Cleveland itself. One mound, south of Brecksville, contained a cache of trade goods within a 6-sided stone crypt. A smaller mound between Willowick and Eastlake contained several ceremonial spear points of chert from Illinois - altogether signs of a wide range of trade. At Cleveland's W. 54th St. Division waterworks there was probably a mound and a Hopewellian spear tip was found there.

After AD 400 maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

dominated. Mounds were built no more, but the number of different groups increased, with winter villages at the Cuyahoga, Rocky

''Rocky'' is a 1976 American sports drama film directed by John G. Avildsen and written by and starring Sylvester Stallone. It is the first installment in the ''Rocky'' franchise and stars Talia Shire, Burt Young, Carl Weathers, and Burges ...

and Lower Chagrin River

The Chagrin River is located in Northeast Ohio. The river has two branches, the Aurora Branch and East Branch. Of three hypotheses as to the origin of the name, the most probable is that it is a corruption of the name of a Frenchman, Sieur de Segu ...

s. Small, circular houses contained one or two fire hearths and storage pits. Tools and ornaments made of antler and bone were found. During the spring, people lived camps along the lakeshore ridges, along ponds and bogs, or headwaters of creeks, where they collected plants and fished.

Between AD 1000 and 1200 oval houses with single-post constructions dominated the summer villages, the emphasis on burial ceremony declined, but became more personal and consisted of ornaments, or personal tools.

From 1200 to 1600 Meso-American influence mediated by the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

could be traced, in Cleveland in new ceramic and house styles, new crops ( common beans), and the presence of materials traded from southern centers. This influence was even stronger within the Fr. Ancient group, probably ancestors of later Shawnees. At this time, there was an obvious difference in archaeological findings from the areas of Black River, Sandusky River

The Sandusky River ( wyn, saandusti; sjw, Potakihiipi ) is a tributary to Lake Erie in north-central Ohio in the United States. It is about longU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Ma ...

and Lake Erie Islands westwards on the one hand and Greater Cleveland

The Cleveland metropolitan area, or Greater Cleveland as it is more commonly known, is the metropolitan area surrounding the city of Cleveland in Northeast Ohio, United States. According to the 2020 United States Census results, the five-county ...

eastwards on the other.

Between 1300 and 1500 agriculture became predominant, especially beans

A bean is the seed of several plants in the family Fabaceae, which are used as vegetables for human or animal food. They can be cooked in many different ways, including boiling, frying, and baking, and are used in many traditional dishes thr ...

and new varieties of maize. Larger villages were inhabited in summer and fall. Small camps diminished and the villages became larger as well as the houses, which became rectangular. Some of the villages became real fortresses. During the later Whittlesey Tradition Whittlesey culture is an archaeological designation for a Native American people, who lived in northeastern Ohio during the Late Precontact and Early Contact period between A.D. 1000 to 1640. By 1500, they flourished as an agrarian society by 1500 ...

burial grounds were placed outside the villages, but still close to them. These villages were in use all year round.

The final Whittlesey Tradition, beginning at about 1500, shows long-houses, fortified villages, and sweat lodges can be traced. But the villages in and around Cleveland reported by Charles Whittlesey, are gone. It was likely a warlike time, as the villages were even more strongly fortified than before. Cases of traumatic injury, nutritional deficiency, and disease were also found. It is obvious that the population declined until about 1640. One reason is probably the little ice-age beginning at about 1500. The other reason is probably permanent warfare. It seems that the region of Cleveland was uninhabited between 1640 and 1740.

18th and 19th centuries

Survey and establishment, 1796–1820

Cuyahoga River

The Cuyahoga River ( , or ) is a river located in Northeast Ohio that bisects the City of Cleveland and feeds into Lake Erie.

As Cleveland emerged as a major manufacturing center, the river became heavily affected by industrial pollution, so m ...

. Cleaveland quickly saw the land, which had previously belonged to Native Americans, as an ideal location for the "capital city" of the Connecticut Western Reserve

The Connecticut Western Reserve was a portion of land claimed by the Colony of Connecticut and later by the state of Connecticut in what is now mostly the northeastern region of Ohio. The Reserve had been granted to the Colony under the terms o ...

. Cleaveland and his surveyors quickly began making plans for the new city. He paced out a nine-and-a-half-acre Public Square, similar to those in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. His surveyors decided upon the name, Cleaveland, after their leader. In October, Cleaveland returned to Connecticut where he pursued his ambition in political, military, and law affairs, never once returning to Ohio.

Schoolteachers Job Phelps Stiles (born c. 1769 in Granville, Massachusetts

Granville is a town in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,538 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The town is named for John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granv ...

) and his wife Talitha Cumi Elderkin (born 1779 in Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since t ...

) were two of only three original settlers who stayed there over the first winter of 1796–1797 when, attended by Seneca Native American women, Talitha Cumi gave birth to Charles Phelps Stiles, the first white child born in the Western Reserve

The Connecticut Western Reserve was a portion of land claimed by the Colony of Connecticut and later by the state of Connecticut in what is now mostly the northeastern region of Ohio. The Reserve had been granted to the Colony under the terms o ...

. They lived at first on Lot 53, the present corner of Superior Avenue

Superior Avenue is the main wide thoroughfare and part of U.S. Route 6 in Ohio in Downtown Cleveland, the largest and most populated city of Northeast Ohio. Superior runs through the central hub of Cleveland, Public Square. However, the only traff ...

and West 3rd Street adjacent to the future Terminal Tower

Terminal Tower is a 52-story, , landmark skyscraper located on Public Square in Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, United States. Built during the skyscraper boom of the 1920s and 1930s, it was the second-tallest building in the world when it was com ...

, but later moved southeast to higher ground in Newburgh, Ohio to escape malarial conditions in the lower Cuyahoga Valley. The first permanent European settler in Cleaveland was Lorenzo Carter

Major Lorenzo Carter was the first permanent settler in Cleveland, Ohio, United States.

Born in 1767, Carter spent his early years in Warren, Connecticut, where he visited the local library frequently and developed an appreciation of books. W ...

, who built a large log cabin on the banks of the Cuyahoga River.

Though not initially apparent — the settlement was adjacent to swampy lowlands and the harsh winters did not encourage settlement — Cleaveland's location ultimately proved providential. It was for that reason that Cleaveland was selected as the seat of Cuyahoga County

Cuyahoga County ( or ) is a large urban county located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Ohio. It is situated on the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S.-Canada maritime border. As of the 2020 census, its population was 1 ...

in 1809, despite protests from nearby rival Newburgh. Cleaveland's location also made it an important supply post for the U.S. during the Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes called the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, on Lake Erie off the shore of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of the Briti ...

in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

. Locals adopted Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

as a civic hero and erected a monument in his honor decades later. Largely through the efforts of the settlement's first lawyer Alfred Kelley

Alfred Kelley (November 7, 1789—December 2, 1859) was a banker, canal builder, lawyer, railroad executive, and state legislator in the state of Ohio in the United States. He is considered by historians to be one of the most prominent commerci ...

, the village of Cleaveland was incorporated on December 23, 1814. In the municipal first elections on June 5, 1815, Kelley was unanimously elected the first president of the village. He held that position for only a few months, resigning on March 19, 1816.

Village to city, 1820–1860

Cleveland began to grow rapidly after the completion of theOhio and Erie Canal

The Ohio and Erie Canal was a canal constructed during the 1820s and early 1830s in Ohio. It connected Akron with the Cuyahoga River near its outlet on Lake Erie in Cleveland, and a few years later, with the Ohio River near Portsmouth. It a ...

in 1832, turning the village into a key link between the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

and the Great Lakes, particularly once the city railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

links were added. The spelling of the city's name was changed in 1831 by ''The Cleveland Advertiser'', an early local newspaper. In order for the name to fit on the newspaper's masthead, the first "a" was dropped, reducing the city's name to ''Cleveland''. The new spelling stuck, and long outlasted the ''Advertiser'' itself.

In 1822, a young, charismatic New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

lawyer, John W. Willey

John Wheelock Willey (1797 – July 9, 1841) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as the first Mayor of Cleveland, Ohio from 1836 to 1837.

Born in New Hampshire, Willey was educated in Dartmouth, Massachusetts and stud ...

, arrived in Cleveland and quickly established himself in the growing village. He became a popular figure in local politics and wrote the Municipal Charter as well as several of the original laws and ordinances. Willey oversaw Cleveland's official incorporation as a city in 1836 and was elected the town's first official mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

for two terms. With James Clark and others, Willey bought a section of the Flats

Flat or flats may refer to:

Architecture

* Flat (housing), an apartment in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and other Commonwealth countries

Arts and entertainment

* Flat (music), a symbol () which denotes a lower pitch

* Flat (soldier), ...

with plans to develop it into Cleveland Centre, a mixed residential and commercial district. Willey then purchased a piece of land from the southeast section of Ohio City across from Columbus Street in Cleveland. Willey named the new territory Willeyville and subsequently built a bridge connecting the two parts, calling it Columbus Street Bridge. The bridge siphoned off commercial traffic to Cleveland before it could reach Ohio City's mercantile district.

These actions aggravated citizens of Ohio City, and brought to the surface a fierce rivalry between the small town and Cleveland. Ohio City citizens rallied for "Two Bridges or None!". In October 1836, they violently sought to stop the use of Cleveland's new bridge by bombing the western end of it. However, the explosion caused little damage. A group of 1,000 Ohio City volunteers began digging deep ditches at both ends of the bridge, making it impossible for horses and wagons to reach the structure. Some citizens were still unsatisfied with this and took to using guns, crowbars, axes, and other weapons to finish off the bridge. They were then met by Willey and a group of armed Cleveland militiamen. A battle ensued on the bridge, with two men seriously wounded before the county sheriff arrived to stop the conflict and make arrests. The confrontation could have escalated into all out war between Cleveland and Ohio City, but was avoided by a court injunction. The two cities eventually made amends, and Ohio City was annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

by Cleveland in 1854.

The Columbus bridge became an important asset for Cleveland, permitting produce to enter the city from the surrounding hinterlands and allowing it to build its mercantile base. This was greatly increased with the coming of the Ohio and Erie Canal which realized the city's potential as a major Great Lakes port. Later, the growing town flourished as a halfway point for iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the ...

coming from Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

across the Great Lakes and for coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

and other raw materials coming by rail from the south. It was in this period that Cleveland saw its first significant influx of immigrants, particularly from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

and the German states.

Civil War, 1861–1865

Strongly influenced by its New England roots, Cleveland was home to a vocal group of

Strongly influenced by its New England roots, Cleveland was home to a vocal group of abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

who viewed slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

as a moral evil. Code-named "Station Hope", the city was a major stop on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

for escaped African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

slaves en route to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. However, not all Clevelanders opposed slavery outright and views on the slaveholding South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

varied based on political affiliation. Nevertheless, as Bertram Wyatt-Brown noted, the city's "record of sympathy and help for the black man's plight in America matched, if not exceeded, that of any other metropolitan center in North America, with the exception, perhaps, of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

and Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

."

In the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

won 58% of the vote in 9 of Cleveland's 11 wards. In February 1861, the president-elect visited Cleveland on his way from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

to his inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugu ...

in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

and was greeted by a massive reception. However, as the war loomed closer, the partisan rhetoric of Cleveland newspapers became more and more heated. The pro- Republican ''Cleveland Herald and Gazette'' celebrated Lincoln's victory "as one of right over wrong, of Unionists over secession-minded southern Democrats," while another Republican paper, ''The Cleveland Leader

''The Cleveland Leader'' was a newspaper published in Cleveland from 1854 to 1917.

History

The ''Cleveland Leader'' was created in 1854 by Edwin Cowles, who merged a variety of abolitionist, pre-Republican Party titles under the ''Leader''. Fr ...

'' dismissed threats of Southern secession. By contrast, the pro- Democratic ''Plain Dealer

''The Plain Dealer'' is the major newspaper of Cleveland, Ohio, United States. In fall 2019, it ranked 23rd in U.S. newspaper circulation, a significant drop since March 2013, when its circulation ranked 17th daily and 15th on Sunday.

As of M ...

'' argued that Lincoln's election would mean the imminent secession of the South. When the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

finally erupted in April 1861, Cleveland Republicans and War Democrats decided to temporarily put aside their differences and unite as the Union party in support of the war effort against the Confederacy. However, this uneasy coalition in support of the Union did not go untested.

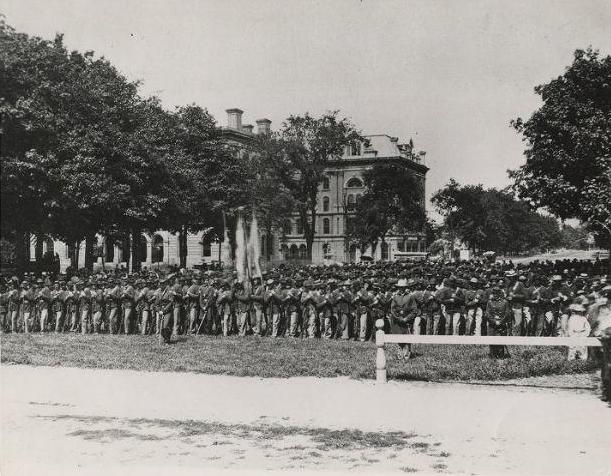

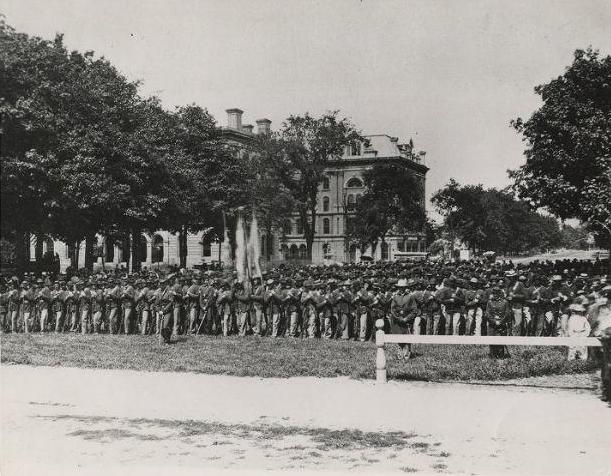

The Civil War years brought an economic boom to Cleveland. The city was making the transition from a small town into an industrial giant. Local industries manufactured railroad iron, gun carriages, gun carriage axles, and gun powder. In 1863, "22% of all ships built for use on the Great Lakes were built in Cleveland," a figure that jumped to 44% by 1865. By 1865, Cleveland's banks "held $2.25 million in capital and $3.7 million in deposits." When the war ended, the city welcomed home its returning troops by treating them to a meal and welcoming ceremony at Public Square. Decades later, in July 1894, those Clevelanders serving the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

would be honored with the opening of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. After Lincoln's assassination in 1865, his casket passed through Cleveland as thousands of onlookers observed the procession.

Industrial growth, 1865–1899

The Civil War vaulted Cleveland into the first rank of American

The Civil War vaulted Cleveland into the first rank of American manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer to ...

cities and fueled unprecedented growth. It became home to numerous major steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

production firms and, in 1883, Samuel Mather co-founded Pickands Mather and Company in the city, specializing in shipping and iron mining. Cleveland also became one of the five main oil refining

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liquefi ...

centers in the U.S. In 1870, Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

began as a partnership based in Cleveland, between John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Henry M. Flagler, and Samuel Andrews. Many mansions were built along the city's more prominent streets, such as the Southworth House along Prospect Avenue, and those on Millionaire's Row, on Euclid Avenue.

Along with the economic boom

An economic expansion is an increase in the level of economic activity, and of the goods and services available. It is a period of economic growth as measured by a rise in real GDP. The explanation of fluctuations in aggregate economic activi ...

, Cleveland's immigrant population continued to grow. By 1870, the city's population had shot up to 92,829, more than doubling its 1860 population of 43,417, with a foreign-born population of 42%. In addition to the Irish and the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, mass numbers of new immigrants, particularly from Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, came to the city, attracted by the prospect of jobs and the promise of a better future in America. By 1890, the year when the Cleveland Arcade was opened to the public, Cleveland had become the nation's 10th largest city, with a population of 261,353.

Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

urban growth fostered the need for efficient police and fire protection, decent housing, public education, sanitation and health services, transportation, and better roads and streets. Industrial growth was also accompanied by significant strikes and labor unrest, as workers demanded better working conditions. In 1881–86, 70-80% of strikes were successful in improving labor conditions in Cleveland. The Cleveland Streetcar Strike of 1899 was one of the more violent instances of labor unrest in the city during this period.

Politically, the Republicans became the dominant political party in postbellum Cleveland. The main architect of this development was industrialist Mark Hanna, who entered politics when he was elected to the Cleveland Board of Education

Cleveland Metropolitan School District, formerly the Cleveland Municipal School District, is a public school district in the U.S. state of Ohio that serves almost all of the city of Cleveland. The district covers 79 square miles. The Clevelan ...

around 1869 and became a political boss

In politics, a boss is a person who controls a faction or local branch of a political party. They do not necessarily hold public office themselves; most historical bosses did not, at least during the times of their greatest influence. Numerous of ...

. Hanna was eventually challenged by Republican Robert E. McKisson, who became mayor in 1895 and launched the construction of a new city water and sewer system. Vehemently anti-Hanna, McKisson created a powerful political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership co ...

to vie for control of the local Republican party. He padded the payroll with his political cronies, expanded the activities of government, and called for city ownership of all utilities. After serving two terms, he was soundly defeated by an alliance of Democrats and Hanna Republicans.

20th century

The Progressive Era, 1900–1919

Early in the 20th century, Cleveland was a city on the rise and was known as the "Sixth City" due to its position as the sixth largest U.S. city at the time. Its businesses included automotive companies such asPeerless

Peerless may refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Peerless Motor Company, an American automobile manufacturer.

* Peerless Brewing Company, in Birkenhead, UK

* Peerless Group, an insurance and financial services company in India

* Peerless Re ...

, People's, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Chandler, and Winton, maker of the first car driven across the U.S. Other manufacturers in Cleveland produced steam-powered cars, which included those by White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

and Gaeth

Gaeth was an American steam automobile manufactured in Cleveland, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 milli ...

, and electric car

An electric car, battery electric car, or all-electric car is an automobile that is propelled by one or more electric motors, using only energy stored in batteries. Compared to internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, electric cars are quiet ...

s produced by Baker

A baker is a tradesperson who baking, bakes and sometimes Sales, sells breads and other products made of flour by using an oven or other concentrated heat source. The place where a baker works is called a bakery.

History

Ancient history

Si ...

. The city's population also continued to grow. Alongside new immigrants, African American migrants from the rural South arrived in Cleveland (among other Northeastern and Midwestern cities) as part of the Great Migration for jobs, constitutional rights, and relief from racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

.

However, it was clear that the city's government needed major reform. After a succession of Hanna Republicans and McKisson's corrupt political machine, Cleveland voted for change, putting progressive Democrat Tom L. Johnson

Tom Loftin Johnson (July 18, 1854 – April 10, 1911) was an American industrialist, Georgist politician, and important figure of the Progressive Era and a pioneer in urban political and social reform. He was a U.S. Representative from 1891 to ...

into the mayor's office in 1901. Johnson led reforms for "home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wi ...

, three-cent fare, and just taxation". He initiated the Group Plan

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic iden ...

of 1903 as well as the Mall

Mall commonly refers to a:

* Shopping mall

* Strip mall

* Pedestrian street

* Esplanade

Mall or MALL may also refer to:

Places Shopping complexes

* The Mall (Sofia) (Tsarigradsko Mall), Sofia, Bulgaria

* The Mall, Patna, Patna, Bihar, India

...

, the earliest and most complete civic-center plan for a major city outside of Washington, D.C. Together with cabinet members Newton D. Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

and Harris R. Cooley, Johnson also worked to professionalize city hall.

Johnson's progressive associate Newton Baker was elected mayor in 1911. An advocate of municipal home rule, Baker helped write the Ohio constitutional amendment of 1912 granting municipalities the right of self-governance. He played a prominent role in Cleveland's first home rule charter, which passed in 1913. In 1913 he went to Washington as Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. He subsequently returned to practicing law in Cleveland and became the founder of the law firm

A law firm is a business entity formed by one or more lawyers to engage in the practice of law. The primary service rendered by a law firm is to advise clients (individuals or corporations) about their legal rights and responsibilities, and to ...

Baker, Hostetler & Sidlo (today BakerHostetler

BakerHostetler is an American law firm founded in 1916. One of the firm's founders, Newton D. Baker, was U.S. Secretary of War during World War I, and former Mayor of Cleveland, Ohio.

History

, the firm was ranked the 73rd-largest law firm in ...

).

The spirit of the Progressive era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

had a lasting impact on Cleveland. The era of the City Beautiful movement

The City Beautiful Movement was a reform philosophy of North American architecture and urban planning that flourished during the 1890s and 1900s with the intent of introducing beautification and monumental grandeur in cities. It was a part of the ...

in Cleveland architecture, the period saw wealthy patrons support the establishment of the city's major cultural institutions. The most prominent among them were the Cleveland Museum of Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, located in the Wade Park District, in the University Circle neighborhood on the city's east side. Internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian and Egyptian ...

(CMA), which opened in 1916, and the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Se ...

, established in 1918. From its formation, the CMA offered admission free to the public "for the benefit of all the people forever."

Baker was succeeded as mayor by Harry L. Davis. Davis established the Mayor's Advisory War Committee, formed in 1917 to assist with aiding the American effort in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. After the war ended in 1918, the nation became gripped by the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. The local branch of the Cleveland Socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

, led by Charles Ruthenberg, together with the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW), demanded better working conditions for the largely immigrant and migrant workers. Tensions eventually exploded in the violent Cleveland May Day Riots of 1919, in which socialist and IWW demonstrators clashed with anti-socialists. The home of Mayor Davis was also bombed by the Italian anarchist

Italian anarchism as a movement began primarily from the influence of Mikhail Bakunin, Giuseppe Fanelli, and Errico Malatesta. Rooted in collectivist anarchism, it expanded to include illegalist individualist anarchism, mutualism, anarcho-sy ...

followers of Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 1861–1931) was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e. the use of violence to eliminate those he viewed as tyrant ...

. In response, Davis campaigned for the expulsion of all "Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

" from America. Faced with the issue of the riots and his own ambitions to become governor of Ohio, Davis resigned in May 1920. He would later serve as a mayor again in 1933.

The Roaring Twenties, 1920–1929

TheRoaring Twenties

The Roaring Twenties, sometimes stylized as Roaring '20s, refers to the 1920s decade in music and fashion, as it happened in Western society and Western culture. It was a period of economic prosperity with a distinctive cultural edge in th ...

was a prosperous decade for Cleveland. By 1920, the year in which the Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central division. Since , they have ...

won their first World Series championship, Cleveland had grown into a densely-populated metropolis of 796,841 with a foreign-born population of 30%, making it the fifth largest city in the nation. Despite the national immigration restrictions of the 1920s, the city's population continued to grow. In 1923 the speed nut was invented by Cleveland industrialist and inventor Albert Tinnerman. In order to solve the problem of the porcelain on the family company's stoves cracking when panels were screwed tightly together, Albert invented the speed nut. This revolutionized assembly lines in the automobile and airline industries.

The decade also saw the establishment of Cleveland's Playhouse Square

Playhouse Square is a theater district in downtown Cleveland, Ohio, United States. It is the largest performing arts center in the US outside of New York City (only Lincoln Center is larger). Constructed in a span of 19 months in the early 1920s ...

and the rise of the risqué Short Vincent entertainment district. The Bal-Masque balls of the avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretica ...

Kokoon Arts Club

The Kokoon Arts Club, sometimes spelled Kokoon Arts Klub, was a Bohemian artists group founded in 1911 by Carl Moellman, William Sommer and Elmer Brubeck to promote Modernism in Cleveland, Ohio. Moellman had been a member of New York City's ...

scandalized the city. The northward migration of musicians from brought jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

to Cleveland; new jazz talent also rose from Cleveland Central High School

''For other schools, see Cleveland High School (disambiguation)''

Cleveland Central High School is a public high school in Cleveland, Mississippi. The sole high school of the Cleveland School District, it serves Cleveland, Boyle, Renova, and ...

. The era of the flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptab ...

marked the beginning of the golden age in Downtown Cleveland

Downtown Cleveland is the central business district of Cleveland, Ohio. The economic and symbolic center of the city and the Cleveland-Akron-Canton, OH Combined Statistical Area, it is Cleveland's oldest district, with its Public Square laid out ...

retail, centered on major department stores Higbee's

Higbee's was a department store founded in 1860 in Cleveland, Ohio. In 1987, Higbee's was sold to the joint partnership of Dillard's department stores and Youngstown-based developer, Edward J. DeBartolo. The stores continued to operate unde ...

, Bailey's, the May Company, Taylor's, Halle's

Halle Brothers Co., commonly referred to as Halle's, was a department store chain based in Cleveland, Ohio. During most of its 91-year history, Halle's focused on higher-end merchandise which it combined with personal service. The company was t ...

, and Sterling Lindner Davis, which collectively represented one of the largest and most fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fash ...

able shopping districts in the country, often compared to New York's Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping ...

. In 1929, the city hosted the first of many National Air Races

The National Air Races (also known as Pulitzer Trophy Races) are a series of pylon and cross-country races that have taken place in the United States since 1920. The science of aviation, and the speed and reliability of aircraft and engines grew ...

, and Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

flew to the city from Santa Monica, California

Santa Monica (; Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 U.S. Census population was 93,076. Santa Monica is a popular resort town, owing to ...

in the Women's Air Derby (nicknamed the "Powder Puff Derby" by Will Rogers

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahom ...

).

In politics, the city began a brief experiment with a council–manager government

The council–manager government is a form of local government used for municipalities, counties, or other equivalent regions. It is one of the two most common forms of local government in the United States along with the mayor–council gover ...

system in 1924. William R. Hopkins, who became the first city manager

A city manager is an official appointed as the administrative manager of a city, in a "Mayor–council government" council–manager form of city government. Local officials serving in this position are sometimes referred to as the chief exec ...

, oversaw the development of parks, the Cleveland Municipal Airport (later renamed Hopkins International Airport), and improved welfare services. In 1923, the building of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is the Cleveland-based headquarters of the U.S. Federal Reserve System's Fourth District. The district is composed of Ohio, western Pennsylvania, eastern Kentucky, and the northern panhandle of West Virginia ...

on East 6th Street and Superior Avenue was opened, and in 1925, the main building of the Cleveland Public Library

Cleveland Public Library, located in Cleveland, Ohio, operates the Main Library on Superior Avenue in downtown Cleveland, 27 branches throughout the city, a mobile library, a Public Administration Library in City Hall, and the Ohio Library for th ...

on Superior was opened under the supervision of head librarian Linda Eastman

Linda Anne Eastman (July 7, 1867 – April 5, 1963) was an American librarian. She was selected by the American Library Association (ALA) as one of the 100 most important librarians of the 20th century.

Eastman served as the head Librarian of ...

, the first woman ever to lead a major library system in the world. Both buildings were designed by the Cleveland architectural firm Walker and Weeks. In 1926, the Van Sweringen brothers, who had previously worked to improve Cleveland's trolley and rapid program, began construction of the Terminal Tower

Terminal Tower is a 52-story, , landmark skyscraper located on Public Square in Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, United States. Built during the skyscraper boom of the 1920s and 1930s, it was the second-tallest building in the world when it was com ...

skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Modern sources currently define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition. Skyscrapers are very tall high-ri ...

in 1926 and, by the time it was dedicated in 1930, Cleveland had a population of over 900,000. Until 1967, the tower was the tallest building in the world outside of New York.

Before Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

, Cleveland had been a major center of the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

, with the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

having been founded there. The Eighteenth Amendment prohibiting the sale and manufacturing of alcohol first took effect in Cleveland on May 27, 1919. However, it was not well-enforced in the city. Cleveland alcohol stocks declined when the Prohibition Bureau sent an administrator and federal agents as the amendment and the Volstead Act

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was an act of the 66th United States Congress, designed to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919), which established the prohibition of alcoholic d ...

became law in January 1920. With prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

, Cleveland, like other major American cities saw the rise of organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

. Little Italy

Little Italy is a general name for an ethnic enclave populated primarily by Italians or people of Italian ancestry, usually in an urban neighborhood. The concept of "Little Italy" holds many different aspects of the Italian culture. There are ...

's Mayfield Road Mob

The Cleveland crime family or Cleveland Mafia is the collective name given to a succession of Italian-American organized crime gangs based in Cleveland, Ohio, in the United States. A part of the Italian-American Mafia (or ''Cosa Nostra'') pheno ...

was notorious for smuggling bootleg alcohol out of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

to Cleveland. The mob's members included Joe Lonardo, Nathan Weisenburg, the seven Porello brothers (four of whom were killed), Moses Donley, Paul Hackett, and J.J. Schleimer. These names and Milano, Furgus, and O'Boyle held the same connotation as Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. Speakeasies

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States ...

began appearing all over the city. An anti-Prohibition group found 2,545 such locations throughout Cleveland.

The Great Depression, 1929–1939

On October 24, 1929, the stock market crashed, plunging the entire nation into theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. The crash hit Cleveland hard, with industrialist Cyrus Eaton

Cyrus Stephen Eaton Sr. (December 27, 1883 – May 9, 1979) was a Canadian-American investment banker, businessman and philanthropist, with a career that spanned seventy years.

For decades Eaton was one of the most powerful financiers in the ...

once stating that the city was "hurt more by the Depression than any other city in the United States." By 1933, approximately fifty percent of Cleveland's industrial workers were left unemployed by the Depression.

Anti-Prohibition sentiment continued to grow. Tired of gang wars

is a 1989 2D beat 'em up arcade game developed by Alpha Denshi and published by SNK.

Plot

The setting takes place in New York City, following martial artists Mike and Jackie, who heard an evil gang led by the antagonist, Jaguar, are terrorizin ...

in Cleveland and Chicago, Fred G. Clark founded an anti-gang, anti-Prohibition group known as the Crusaders. Cleveland became their national headquarters, and by 1932 the Crusaders claimed one million members. Formed in Chicago, the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform

Pauline Morton Sabin (April 23, 1887 – December 27, 1955) was an American prohibition repeal leader and Republican party official. Born in Chicago, she was a New Yorker who founded the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR). ...

was another group that rose to prominence during this period. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, Prohibition appeared to be near an end. Together, the Crusaders, the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment

The Association Against the Prohibition Amendment was established in 1918 and became a leading organization working for the repeal of prohibition in the United States. It was the first group created to fight Prohibition, also known as the 18th ...

, and the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform formed the Ohio Repeal Council, and Prohibition was finally repealed in Cleveland on December 23, 1933.

Politically, the city abolished the city manager system under Daniel E. Morgan and returned to the mayor–council (strong mayor) system. After a brief stint in office by Democratic Mayor Ray T. Miller

Raymond Thomas Miller, Sr. (January 10, 1893 – July 13, 1966), commonly known as Ray T. Miller, was an American politician who served as the 43rd mayor of Cleveland, and the chairman of the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party for over twenty ...

, who would later serve as the powerful chairman of the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party, Harry L. Davis, who had previously served as mayor, returned. However, Davis exhibited increasing incompetence in office and the city became a haven for criminal activity. The police department was corrupt, prostitution and illegal gambling were rampant, and organized crime was still abundant.Miller and Wheeler, p. 142.

In the next election, Harold H. Burton became the city's new mayor. Burton, a lawyer from New England and future Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

, sought to get Cleveland back on its feet. He accomplished this with the help of his newly appointed Safety Director, Eliot Ness

Eliot Ness (April 19, 1903 – May 16, 1957) was an American Prohibition agent known for his efforts to bring down Al Capone and enforce Prohibition in Chicago. He was the leader of a team of law enforcement agents, nicknamed The Untouchables. ...

, who previously served as Chief Investigator of the Prohibition Bureau for Chicago and Ohio, and played an important role in putting Al Capone behind bars. Ness made a name for himself in Cleveland by first and foremost cleaning up the city's police department. As the head of the city's Safety Directorate, Ness introduced a new police district system in Cleveland, fired corrupt and incompetent officers from the force, and replaced them with talented rookies and unrecognized veterans. During Ness's tenure as Safety Director, crime dropped significantly in the city. He also improved traffic safety and orchestrated raids on such notorious gambling spots as the Harvard Club.

A center of union activity, the city saw significant labor struggles in this period, including strikes by workers against Fisher Body

Fisher Body was an automobile coachbuilder founded by the Fisher brothers in 1908 in Detroit, Michigan. A division of General Motors for many years, in 1984 it was dissolved to form other General Motors divisions. Fisher & Company (originally All ...

in 1936 and against Republic Steel

Republic Steel is an American steel manufacturer that was once the country's third largest steel producer. It was founded as the Republic Iron and Steel Company in Youngstown, Ohio in 1899. After rising to prominence during the early 20th Centu ...

in 1937. The city was also aided by major federal works projects sponsored by President Roosevelt's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

. In commemoration of the centennial of Cleveland's incorporation as a city, the Great Lakes Exposition debuted in June 1936 at the city's North Coast Harbor, along the Lake Erie shore north of downtown. Conceived by Cleveland's business leaders as a way to revitalize the city during the Depression, it drew four million visitors in its first season, and seven million by the end of its second and final season in September 1937.

World War II and postwar, 1940–1962

On December 7, 1941,

On December 7, 1941, Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

attacked Pearl Harbor and declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

on the United States. One of the victims of the attack was a Cleveland native, Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd. The attack signaled America's entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. A major hub of the " Arsenal of Democracy", Cleveland under Democratic Mayor Frank Lausche

Frank John Lausche (; November 14, 1895 – April 21, 1990) was an American Democratic politician from Ohio. He served as the 47th mayor of Cleveland and the 55th and 57th governor of Ohio, and also served as a United States Senator from Ohio ...