Helensburgh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Helensburgh (; gd, Baile Eilidh) is an affluent coastal town on the north side of the

Helensburgh is northwest of

Helensburgh is northwest of

Although it has long been known that there are some prehistoric remains in the Helensburgh area, recent fieldwork by the North Clyde Archaeological Society has uncovered more. However the oldest building in the town itself is Ardencaple Castle which was the ancestral home of Clan MacAulay, and the history of which may date back to the twelfth century. Today only one tower of this building remains, the rest having been demolished in 1957–59.

Although it has long been known that there are some prehistoric remains in the Helensburgh area, recent fieldwork by the North Clyde Archaeological Society has uncovered more. However the oldest building in the town itself is Ardencaple Castle which was the ancestral home of Clan MacAulay, and the history of which may date back to the twelfth century. Today only one tower of this building remains, the rest having been demolished in 1957–59.

In 1752 Sir James Colquhoun (died 1786), chief of the

In 1752 Sir James Colquhoun (died 1786), chief of the

Henry Bell (1767–1830) had arrived in Helensburgh by 1806. By training he was a millwright, but he had also worked for a period in a shipyard at

Henry Bell (1767–1830) had arrived in Helensburgh by 1806. By training he was a millwright, but he had also worked for a period in a shipyard at  When Henry Bell came to Helensburgh, roads to

When Henry Bell came to Helensburgh, roads to

Following the arrival of the

Following the arrival of the

Due to its setting Helensburgh has long been considered to have some of Scotland's highest house prices. In a 2006 survey, Helensburgh was shown to be the second most expensive town in which to buy property in Scotland. The older parts of the town are laid out in the gridiron pattern, Helensburgh being an early example of a planned town in Scotland.

The character of the town is further enhanced by its many tree-lined streets, and the cherry blossom in the Spring is a particular feature; a consequence is that the town has been referred to as "the Garden City of the Clyde". In 2016 the Helensburgh Tree Conservation Trust was invited to become a member of The National Tree Collections of Scotland because the range and quality of its street trees; at the time no other Scottish town had received this accolade.

Due to its setting Helensburgh has long been considered to have some of Scotland's highest house prices. In a 2006 survey, Helensburgh was shown to be the second most expensive town in which to buy property in Scotland. The older parts of the town are laid out in the gridiron pattern, Helensburgh being an early example of a planned town in Scotland.

The character of the town is further enhanced by its many tree-lined streets, and the cherry blossom in the Spring is a particular feature; a consequence is that the town has been referred to as "the Garden City of the Clyde". In 2016 the Helensburgh Tree Conservation Trust was invited to become a member of The National Tree Collections of Scotland because the range and quality of its street trees; at the time no other Scottish town had received this accolade.

After the arrival of the railway many attractive villas were built in Helensburgh as the homes of wealthy business people from

After the arrival of the railway many attractive villas were built in Helensburgh as the homes of wealthy business people from

A large proportion of the upper part of the town away from the town centre has been designated as the Upper Helensburgh Conservation Area. Other well-known architects whose work features here are

A large proportion of the upper part of the town away from the town centre has been designated as the Upper Helensburgh Conservation Area. Other well-known architects whose work features here are

Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders Pe ...

, it became part of Argyll and Bute

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020) ...

following local government reorganisation in 1996.

Geography and geology

Helensburgh is northwest of

Helensburgh is northwest of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. The town faces south towards Greenock across the Firth of Clyde, which is approximately wide at this point. Ocean-going ships can call at Greenock, but the shore at Helensburgh is very shallow, although to the west of the town the Gareloch is deep.

Helensburgh lies at the western mainland end of the Highland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a major fault zone that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east. It separates two different geological terranes which give rise to two distinct physiographic terr ...

. This means that the hills to the north of Helensburgh lie in the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

, whereas the land to the south of Helensburgh is in the Lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

or Central Belt

The Central Belt of Scotland is the Demography of Scotland, area of highest population density within Scotland. Depending on the definition used, it has a population of between 2.4 and 4.2 million (the country's total was around 5.4 million in ...

of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. Consequently, there is a wide variety of landscape in the surrounding area – for example, Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; gd, Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'Richens, R. J. (1984) ''Elm'', Cambridge University Press.) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of C ...

(part of Scotland's first National Park) is only over the hill to the north-east of Helensburgh. Although the Highland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a major fault zone that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east. It separates two different geological terranes which give rise to two distinct physiographic terr ...

is not geologically active, very minor earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s do occur occasionally in the area.

During the last ice age, the weight of the ice pushed the land downwards. Consequently, when the ice melted, sea levels were higher than they are now. Evidence of this can clearly be seen in Helensburgh where the first two blocks of streets nearer the sea are built on a raised beach

A raised beach, coastal terrace,Pinter, N (2010): 'Coastal Terraces, Sealevel, and Active Tectonics' (educational exercise), from 2/04/2011/ref> or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin,P ...

. Behind them the land rises up quite steeply for one block and then rises more gently – and this is a former sea cliff which has been eroded. The land, now free of the weight of the ice, is slowly rising up, and the minor local earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s reflect this.

Further evidence of the last ice age can also be seen at low tide, where the beach is dotted with large boulders known as glacial erratic

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundre ...

s – these were carried from a distance inside the glaciers and dropped into their current locations when the glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s melted.

Climate

Helensburgh has an oceanic climate (Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (born 1951), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author and ...

: ''Cfb'').

History

Although it has long been known that there are some prehistoric remains in the Helensburgh area, recent fieldwork by the North Clyde Archaeological Society has uncovered more. However the oldest building in the town itself is Ardencaple Castle which was the ancestral home of Clan MacAulay, and the history of which may date back to the twelfth century. Today only one tower of this building remains, the rest having been demolished in 1957–59.

Although it has long been known that there are some prehistoric remains in the Helensburgh area, recent fieldwork by the North Clyde Archaeological Society has uncovered more. However the oldest building in the town itself is Ardencaple Castle which was the ancestral home of Clan MacAulay, and the history of which may date back to the twelfth century. Today only one tower of this building remains, the rest having been demolished in 1957–59.

Sir James Colquhoun buys the area

In 1752 Sir James Colquhoun (died 1786), chief of the

In 1752 Sir James Colquhoun (died 1786), chief of the Clan Colquhoun

Clan Colquhoun ( gd, Clann a' Chombaich ) is a Scottish clan.

History

Origins of the clan

The lands of the clan Colquhoun are on the shores of Loch Lomond. During the reign of Alexander II, Umphredus de Kilpatrick received from Malduin ...

of Luss

Luss (''Lus'', 'herb' in Gaelic) is a village in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, on the west bank of Loch Lomond. The village is within the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park.

History

Historically in the County of Dunbarton, its origina ...

, bought the land which was to become Helensburgh; at that time it was known by such names as Malig, Millig or Milligs.

In 1776 he placed an advertisement in a Glasgow newspaper seeking to feu the land, and in particular he stated that "bonnet makers, stocking, linen and woolen weavers will meet with encouragement". However his efforts were unsuccessful, partly because roads were rudimentary and also because the shore at Helensburgh made it unattractive to shipping – it was shallow, dotted with large rocks and subject to a prevailing onshore wind.

No precise date is known for the change of name to Helensburgh. However it was probably around 1785 when Sir James decided to name the town after his wife, Lady Helen Sutherland (1717–1791); she was the granddaughter of the 16th Earl of Sutherland

Earl of Sutherland is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created circa 1230 for William de Moravia and is the premier earldom in the Peerage of Scotland. The earl or countess of Sutherland is also the chief of Clan Sutherland.

The origin ...

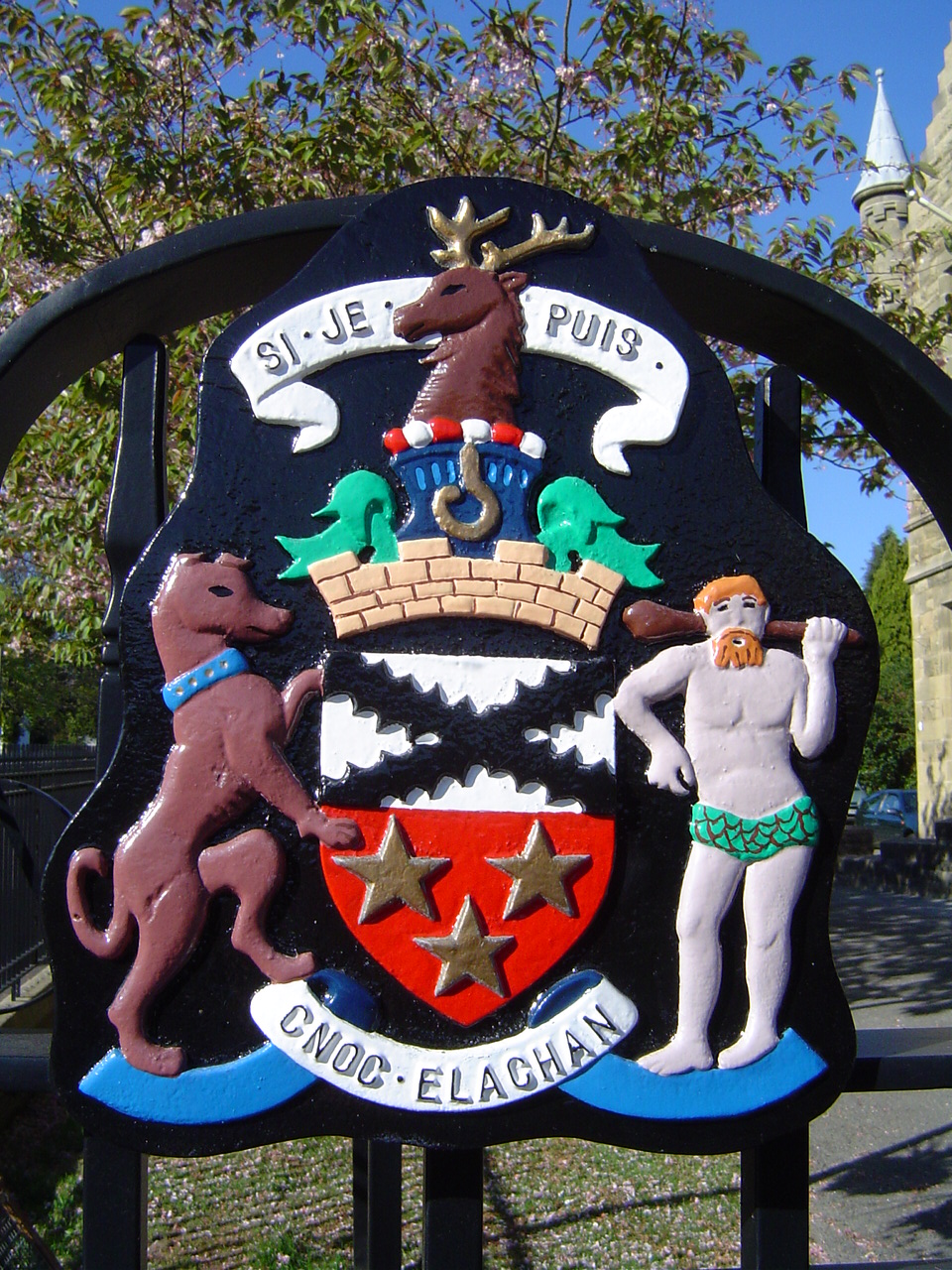

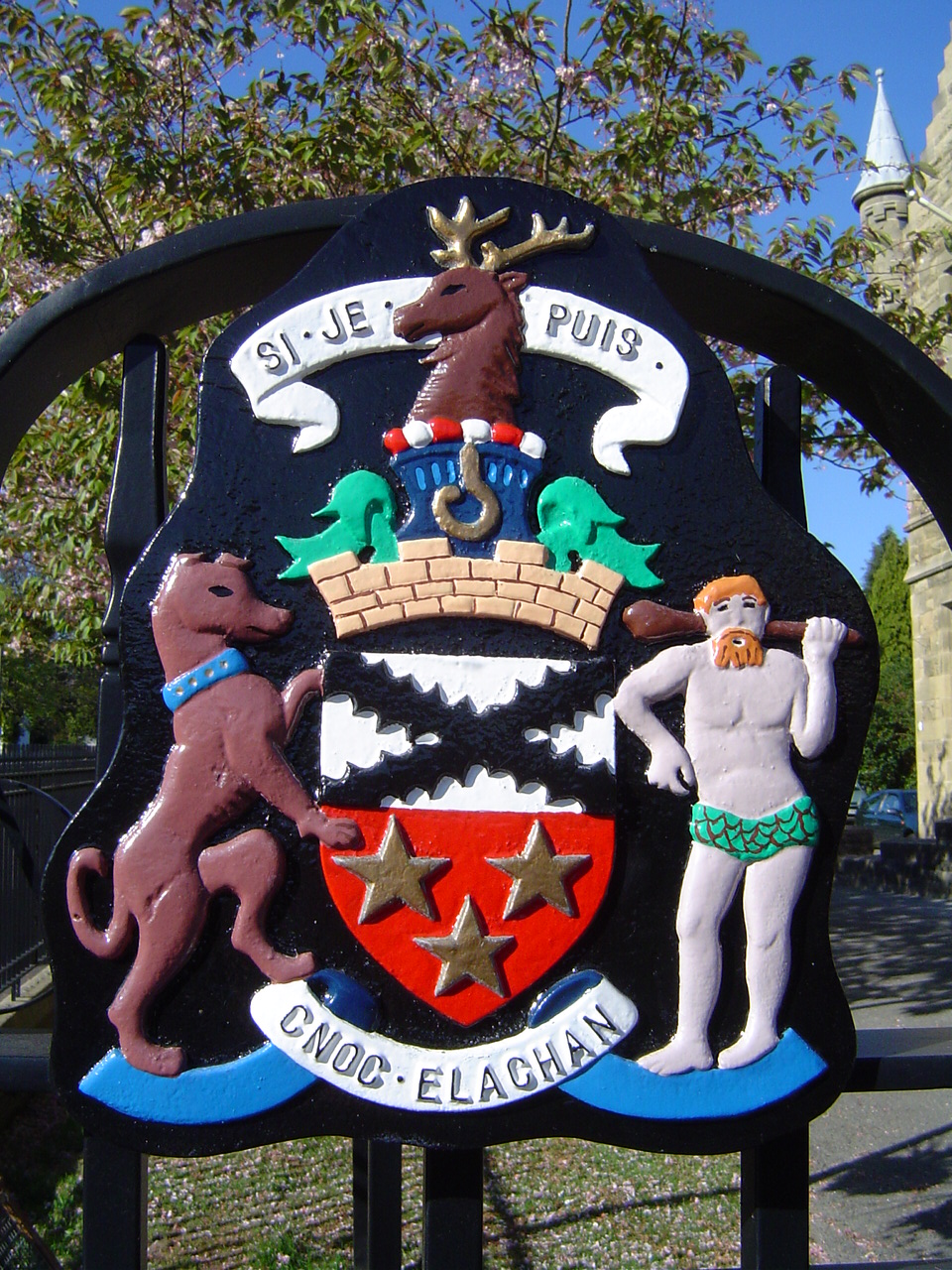

. However, for a few years both the old and new names for the town were in use and it was also known for a time simply as the New Town. The town's coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

is based on those of the Colquhouns and the Sutherlands.

Helensburgh received its burgh charter from King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

in 1802. This was somewhat surprising, as the 1799 Statistical Account of Scotland indicates that Helensburgh only had a population of about 100 at that time. To commemorate the bicentenary of the burgh charter in 2002 many members of Helensburgh Heritage Trust combined to produce a special history book of the town.

Henry Bell and the "Comet"

Henry Bell (1767–1830) had arrived in Helensburgh by 1806. By training he was a millwright, but he had also worked for a period in a shipyard at

Henry Bell (1767–1830) had arrived in Helensburgh by 1806. By training he was a millwright, but he had also worked for a period in a shipyard at Bo'ness

Borrowstounness (commonly known as Bo'ness ( )) is a town and former burgh and seaport on the south bank of the Firth of Forth in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. Historically part of the county of West Lothian, it is a place within the Fal ...

. He probably designed and built the Baths Inn which he and his wife then ran as a hotel; he designed and built other buildings, such as Dalmonach Works at Bonhill

Bonhill ( sco, B'nill; gd, Both an Uillt) is a town in the Vale of Leven area of West Dunbartonshire, Scotland. It is sited on the Eastern bank of the River Leven, on the opposite bank from the larger town of Alexandria.

History

The area is ...

in West Dunbartonshire

West Dunbartonshire ( sco, Wast Dunbairtonshire; gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann an Iar, ) is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. The area lies to the west of the City of Glasgow and contains many of Glasgow's commuter to ...

(now demolished) and St Andrew's Parish Church in Carluke in South Lanarkshire. The Baths Inn later became the Queen's Hotel, and it is now private accommodation as part of Queen's Court at 114 East Clyde Street.

At that time the taking of baths (hot and cold, fresh water and salt water) was considered to be advantageous to the health. As a result of his initiative Helensburgh began to develop as a holiday resort, and Bell also served as the town's first recorded Provost from 1807–09.

When Henry Bell came to Helensburgh, roads to

When Henry Bell came to Helensburgh, roads to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

were in poor condition and the journey by boat could take several days, depending on the strength and direction of the wind and on tidal conditions. Consequently, in 1812 Henry Bell introduced the paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses we ...

''Comet'' to bring guests from Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

in comfort and more speedily to his hotel. The ''Comet'' was the first commercial steamship in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

.

That this vessel and subsequent steamships could travel straight into the wind meant that Helensburgh's shallow shore line was a much smaller problem for sailors. As a result, the town began to grow from a population of about 500 in 1810 to 2,229 by the 1841 Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

. It is difficult to overstate the importance of Bell in Scottish and British economic history; not only was he a pioneer of tourism, but it can also be argued that the later pre-eminence of the River Clyde in shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befo ...

was in no small measure due to him.

The railway arrives

Following the arrival of the

Following the arrival of the Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway

The Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway was independently sponsored to build along the north of the River Clyde. It opened in 1858, joining with an earlier local line serving Balloch. Both were taken over by the powerful North British ...

in 1858 the population of Helensburgh grew even more rapidly, reaching 5,964 in the 1871 Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

. The Municipal Buildings, designed by John Honeyman, were completed in 1879.

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

at this time was developing very rapidly as an industrial city, but this rapid growth caused it to become dirty, smoky and unpleasant. The railway meant that the wealthier business people of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

could now set up home in the fresh air of Helensburgh and commute daily between the two places. This led to the expansion of the town northwards up the hill and the building of many substantial Victorian villas. The best known of these is The Hill House which was designed in 1902–03 by Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. His artistic approach had much in common with European Symbolism. His work, alongside that of his wife Margaret Macdo ...

and which now belongs to the National Trust for Scotland

The National Trust for Scotland for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, commonly known as the National Trust for Scotland ( gd, Urras Nàiseanta na h-Alba), is a Scottish conservation organisation. It is the largest membership organi ...

, see " #Conservation Areas" below for fuller details.

In 1960 the line from Helensburgh Central to Glasgow Queen Street

, symbol_location = gb

, symbol = rail

, image = Queen Street railway station (geograph 6687389).jpg

, caption = Main entrance in 2020

, borough = Glasgow

, country = Scotland

, coordinates =

, grid_name = Grid reference

, grid_positi ...

Low Level and on to Airdrie was electrified with the then revolutionary new Blue Trains providing faster, regular interval services. Unfortunately, equipment problems led to the temporary withdrawal of the Blue Trains which did not return to traffic until late 1961. Since then traffic on this route has risen steadily, helped from October 2010 when two trains each hour commenced running right through to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

via the newly re-opened (and electrified) Airdrie-Bathgate

Bathgate ( sco, Bathket or , gd, Both Chèit) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland, west of Livingston, Scotland, Livingston and adjacent to the M8 motorway (Scotland), M8 motorway. Nearby towns are Armadale, West Lothian, Armadale, Blackburn, ...

line.

By the late 1870s the North British Railway Company (which had become owner of the Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway

The Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway was independently sponsored to build along the north of the River Clyde. It opened in 1858, joining with an earlier local line serving Balloch. Both were taken over by the powerful North British ...

) felt that its steamer services were at a competitive disadvantage, because passengers had to walk from Helensburgh Station, through the town centre and down the pier, thus causing longer journey times. By contrast their competitors on the other side of the Clyde Clyde may refer to:

People

* Clyde (given name)

* Clyde (surname)

Places

For townships see also Clyde Township

Australia

* Clyde, New South Wales

* Clyde, Victoria

* Clyde River, New South Wales

Canada

* Clyde, Alberta

* Clyde, Ontario, a tow ...

, the Caledonian Railway

The Caledonian Railway (CR) was a major Scottish railway company. It was formed in the early 19th century with the objective of forming a link between English railways and Glasgow. It progressively extended its network and reached Edinburgh an ...

and the Glasgow & South Western Railway

The Glasgow and South Western Railway (G&SWR) was a railway company in Scotland. It served a triangular area of south-west Scotland between Glasgow, Stranraer and Carlisle. It was formed on 28 October 1850 by the merger of two earlier railway ...

had stations right beside their piers. The North British therefore proposed to extend the railway line through the town centre from the station on to the pier.

This proposal split opinion in the town down the middle, with Parliament ultimately deciding against it. Consequently, the North British Railway Company decided to build its "station in the sea" at Craigendoran

Craigendoran (Gaelic: ) is a suburb at the eastern end of Helensburgh in Scotland, on the northern shore of the Firth of Clyde. The name is from the Gaelic for "the rock of the otter".

It is served by Craigendoran railway station. Craigendoran pi ...

just outside the eastern boundary of the town, and this opened in 1882. Shipping services stopped in 1972 but Craigendoran railway station remains in use.

In 1894 the West Highland Railway (a subsidiary of the North British Railway by then) was opened from Craigendoran

Craigendoran (Gaelic: ) is a suburb at the eastern end of Helensburgh in Scotland, on the northern shore of the Firth of Clyde. The name is from the Gaelic for "the rock of the otter".

It is served by Craigendoran railway station. Craigendoran pi ...

junction to Fort William, with a new station at Helensburgh Upper. This new railway had no significant effect on the population of the town, but it did alter its appearance, with the construction of a substantial embankment up the hill from Craigendoran and of a deep cutting on the approaches to Helensburgh Upper.

The

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

There are 205 men and 1 woman named on Helensburgh's war memorial in Hermitage Park. In 2020 the Helensburgh War Memorial Project published its researches and added a further 59 "missing names" to the list; all were men. It also gave a variety of explanations as to why these names were not on the war memorial. Helensburgh was a much smaller town at that time: its total population in the 1911 Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

was 8529. If we assume that half of this population were male and if we assume that men between the ages of 18 and 35 made up about a quarter of the male population, then there were 1,066 males of that age in Helensburgh, of whom 264 died; almost a quarter of that age group. A similar proportion were quite possibly seriously injured, both physically and mentally.

There are also war memorials nearby in Rhu, Shandon and Cardross

Cardross (Scottish Gaelic: ''Càrdainn Ros'') is a large village with a population of 2,194 (2011) in Scotland, on the north side of the Firth of Clyde, situated halfway between Dumbarton and Helensburgh. Cardross is in the historic geographical ...

.

Faslane

When theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

broke out in 1939 the British Government was concerned that London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and other ports in the south of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

would become the targets for German bombing. Consequently, they decided to build two military ports in Scotland which would be more difficult for German bombers to reach.

In 1941 Military Port Number 1 opened at Faslane on the Gareloch, 5 miles (8 km) from Helensburgh. A railway was built linking Faslane to the West Highland Line

The West Highland Line ( gd, Rathad Iarainn nan Eilean - "Iron Road to the Isles") is a railway line linking the ports of Mallaig and Oban in the Scottish Highlands to Glasgow in Central Scotland. The line was voted the top rail journey in the ...

. A vast tonnage of wartime supplies was moved through Faslane, and it was also used as a port for troop movements. Much of the area around Helensburgh was taken over by both British and American Armed Forces for a variety of wartime activities.

After the end of the War, Faslane was split in two. The southern half was used by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and the northern half for shipbreaking until 1980. In 1957 the Royal Navy closed its submarine base in Rothesay

Rothesay ( ; gd, Baile Bhòid ) is the principal town on the Isle of Bute, in the council area of Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It lies along the coast of the Firth of Clyde. It can be reached by ferry from Wemyss Bay, which offers an onward rail ...

Bay and transferred it to Faslane. Six years later the British Government decided to buy seaborne nuclear weapons from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and to base them in submarines at Faslane which became known as the Clyde Submarine Base. This decision had a substantial impact on Helensburgh and the surrounding area particularly with the provision of housing for naval personnel. A further increase in the town's population resulted, it rising to 15,852 in the 1991 Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

. From 1996 surface vessels have also been based there, and this caused a change of the official name to Her Majesty's Naval Base Clyde.

The town today

Due to its setting Helensburgh has long been considered to have some of Scotland's highest house prices. In a 2006 survey, Helensburgh was shown to be the second most expensive town in which to buy property in Scotland. The older parts of the town are laid out in the gridiron pattern, Helensburgh being an early example of a planned town in Scotland.

The character of the town is further enhanced by its many tree-lined streets, and the cherry blossom in the Spring is a particular feature; a consequence is that the town has been referred to as "the Garden City of the Clyde". In 2016 the Helensburgh Tree Conservation Trust was invited to become a member of The National Tree Collections of Scotland because the range and quality of its street trees; at the time no other Scottish town had received this accolade.

Due to its setting Helensburgh has long been considered to have some of Scotland's highest house prices. In a 2006 survey, Helensburgh was shown to be the second most expensive town in which to buy property in Scotland. The older parts of the town are laid out in the gridiron pattern, Helensburgh being an early example of a planned town in Scotland.

The character of the town is further enhanced by its many tree-lined streets, and the cherry blossom in the Spring is a particular feature; a consequence is that the town has been referred to as "the Garden City of the Clyde". In 2016 the Helensburgh Tree Conservation Trust was invited to become a member of The National Tree Collections of Scotland because the range and quality of its street trees; at the time no other Scottish town had received this accolade.

Conservation areas

After the arrival of the railway many attractive villas were built in Helensburgh as the homes of wealthy business people from

After the arrival of the railway many attractive villas were built in Helensburgh as the homes of wealthy business people from Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. As a result of this Helensburgh has three Conservation Areas.

The smallest of these is The Hill House Conservation Area, based on the masterpiece of architecture by Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. His artistic approach had much in common with European Symbolism. His work, alongside that of his wife Margaret Macdo ...

, and built for the publisher Walter Blackie. The house, at the top of Upper Colquhoun Street on the north edge of town, is one of the best examples of his style, with startlingly modern interiors incorporating furniture which he also designed.

Unfortunately for almost all its entire life the Hill House has had problems with damp penetration. These were so severe that in 2019 the whole building was enclosed within "The Box"; this is a remarkable structure with a solid roof and chainmail walls. Its purpose is to let the building dry out. Although The Box has planning permission for 5 years, it is not known how long it will take for the building to dry out or what form any subsequent restoration will take.

In 2016 proof was found that another building in the town, long suspected of having been designed by Mackintosh, was actually his work. It was built as the Helensburgh & Gareloch Conservative Club, and the top floor only of this large building is now known as the Mackintosh Club. It is located in the town centre at 40 Sinclair Street above the M & Co shop.

A large proportion of the upper part of the town away from the town centre has been designated as the Upper Helensburgh Conservation Area. Other well-known architects whose work features here are

A large proportion of the upper part of the town away from the town centre has been designated as the Upper Helensburgh Conservation Area. Other well-known architects whose work features here are William Leiper

William Leiper FRIBA RSA (1839–1916) was a Scottish architect known particularly for his domestic architecture in and around the town of Helensburgh.Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott.

In 2019 a third conservation area was set up, this time for the Town Centre. It covers much of the commercial heart of the town, but excludes the pier.

A special local form of transport is the

A special local form of transport is the

It could be argued that the finest church in the town architecturally is St Michael and All Angels at the corner of William Street and West Princes Street. This building for the congregation of the

It could be argued that the finest church in the town architecturally is St Michael and All Angels at the corner of William Street and West Princes Street. This building for the congregation of the

Built as the Victoria Infirmary, the Victoria Integrated Care Centre no longer cares for in-patients and the original building is now little used. However a variety of clinics do take place in buildings in the grounds.

The nearest functioning hospital is the Vale of Leven Hospital in

Built as the Victoria Infirmary, the Victoria Integrated Care Centre no longer cares for in-patients and the original building is now little used. However a variety of clinics do take place in buildings in the grounds.

The nearest functioning hospital is the Vale of Leven Hospital in

Sports are well represented with various football, rugby, cricket, athletics, netball, hockey,

Sports are well represented with various football, rugby, cricket, athletics, netball, hockey,

There are a number of footpaths in and around Helensburgh, and it is also the starting point for some long distance walking and kayaking.

In the town itself there are footpaths inside the Duchess Woods, Argyll & Bute's only local nature reserve. Just outside the town there is an attractive footpath of 2 miles length (3 km) around Ardmore Point.

A longer footpath is the Three Lochs Way which connects

There are a number of footpaths in and around Helensburgh, and it is also the starting point for some long distance walking and kayaking.

In the town itself there are footpaths inside the Duchess Woods, Argyll & Bute's only local nature reserve. Just outside the town there is an attractive footpath of 2 miles length (3 km) around Ardmore Point.

A longer footpath is the Three Lochs Way which connects

A major upgrade to the streets in the town centre has taken place. Pavements have been widened and attractive new surfaces of

A major upgrade to the streets in the town centre has taken place. Pavements have been widened and attractive new surfaces of

Of the three most famous residents of Helensburgh, the only one to have been born in the town was

Of the three most famous residents of Helensburgh, the only one to have been born in the town was

Future British

Future British

Population and employment

In 2008 theGeneral Register Office for Scotland

The General Register Office for Scotland (GROS) ( gd, Oifis Choitcheann a' Chlàraidh na h-Alba) was a non-ministerial directorate of the Scottish Government that administered the registration of births, deaths, marriages, divorces and adopti ...

gave the population of Helensburgh as 13,660. However this is set to grow by 2020, as plans are being developed for around 650 new homes. Helensburgh today acts as a commuter town for nearby Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and also serves as a main shopping centre for the area and for tourists and day trippers attracted to the town's seaside location. Helensburgh is also influenced by the presence of the Clyde Naval Base at Faslane on the Gareloch, which is home to the United Kingdom's submarine fleet with their nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s, as well as a major local employer. A substantial expansion is due to take place there by 2020–21, and this will increase the importance of Faslane to the town even more.

Transport

The town is served by three railway stations. The principal one is Helensburgh Central, the terminus of theNorth Clyde Line

The North Clyde Line (defined by Network Rail as the ''Glasgow North Electric Suburban'' line) is a suburban railway in West Central Scotland. The route is operated by ScotRail Trains. As a result of the incorporation of the Airdrie–Bathga ...

and Craigendoran

Craigendoran (Gaelic: ) is a suburb at the eastern end of Helensburgh in Scotland, on the northern shore of the Firth of Clyde. The name is from the Gaelic for "the rock of the otter".

It is served by Craigendoran railway station. Craigendoran pi ...

at the east end of the town is on the same line. Helensburgh Upper is on the West Highland Line

The West Highland Line ( gd, Rathad Iarainn nan Eilean - "Iron Road to the Isles") is a railway line linking the ports of Mallaig and Oban in the Scottish Highlands to Glasgow in Central Scotland. The line was voted the top rail journey in the ...

; trains from here go to Fort William, Mallaig

Mallaig (; gd, Malaig derived from Old Norse , meaning sand dune bay) is a port in Lochaber, on the west coast of the Highlands of Scotland. The local railway station, Mallaig, is the terminus of the West Highland railway line (Fort Willi ...

and Oban while, in the opposite direction, the Caledonian Sleeper

''Caledonian Sleeper'' is the collective name for overnight sleeper train services between London and Scotland, in the United Kingdom. It is one of only two currently operating sleeper services on the railway in the United Kingdom, the other b ...

provides a direct train service to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. There is also a bus service to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, as well as local bus services within the town and to the Vale of Leven and to Carrick Castle.

A special local form of transport is the

A special local form of transport is the paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses we ...

''Waverley'' which used to call in to Helensburgh pier during summer sailings. It advertises itself as the last sea-going paddle steamer in the world and was launched in 1946 for service from Craigendoran

Craigendoran (Gaelic: ) is a suburb at the eastern end of Helensburgh in Scotland, on the northern shore of the Firth of Clyde. The name is from the Gaelic for "the rock of the otter".

It is served by Craigendoran railway station. Craigendoran pi ...

pier; however Craigendoran pier is now derelict, services having been withdrawn in 1972. Towards the end of 2018 Helensburgh pier was closed to all maritime craft because of its poor condition, and so there is no certainty as to when calls by the "Waverley" will resume.

Religion

Most of the major Scottish Christian denominations have churches in Helensburgh. The biggest of these was theChurch of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

which by 1880 had 5 congregations in the town, each with its own building. However, with falling church attendances, and a vision to rationalise resources to better enable mission, these had all merged by 2015, so that the only Church of Scotland congregation is Helensburgh Parish Church in Colquhoun Square. Helensburgh is the largest Church of Scotland Parish in Scotland.

Since December 2015 the Minister at Helensburgh Parish Church is the Reverend David T. Young.

The Scottish Catholic Church has a significant influence within the town, with a parish church named St Joseph's on Lomond Street. St Joseph's church hall was originally the parish church in Helensburgh.

It could be argued that the finest church in the town architecturally is St Michael and All Angels at the corner of William Street and West Princes Street. This building for the congregation of the

It could be argued that the finest church in the town architecturally is St Michael and All Angels at the corner of William Street and West Princes Street. This building for the congregation of the Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

was designed in 1868 by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson

Sir Robert Rowand Anderson, (5 April 1834 – 1 June 1921) was a Scottish Victorian architect. Anderson trained in the office of George Gilbert Scott in London before setting up his own practice in Edinburgh in 1860. During the 1860s his ...

and today it is the town's only category A listed church.

Education

There are a number of schools in the town, only one of which is private, namely Lomond School. The rest arestate schools

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools (Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary schools that educate all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in pa ...

provided by Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

.

For most children in the town their education takes place within a number of primary schools

A primary school (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and South Africa), junior school (in Australia), elementary school or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary ed ...

provided by Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

, and these in turn feed into the Hermitage Academy, which is the only secondary school in the town provided by Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

.

The primary schools in question are Colgrain, John Logie Baird, and Hermitage Primary. In addition primary schools in the surrounding less-populated area also send their children on to Hermitage Academy; these include such places as Cardross

Cardross (Scottish Gaelic: ''Càrdainn Ros'') is a large village with a population of 2,194 (2011) in Scotland, on the north side of the Firth of Clyde, situated halfway between Dumbarton and Helensburgh. Cardross is in the historic geographical ...

, Rhu, Garelochhead

Garelochhead ( sco, Garelochheid,

gd, Ceann a' Gheàr ...

, Rosneath, gd, Ceann a' Gheàr ...

Kilcreggan

Kilcreggan (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cille Chreagain'') is a village on the Rosneath peninsula in Argyll and Bute, West of Scotland.

It developed on the north shore of the Firth of Clyde at a time when Clyde steamers brought it within easy reach ...

, Arrochar and Luss

Luss (''Lus'', 'herb' in Gaelic) is a village in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, on the west bank of Loch Lomond. The village is within the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park.

History

Historically in the County of Dunbarton, its origina ...

.

Parklands School is also provided by Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

and is a purpose-built school for pupils with Complex Special Educational Needs. The school meets the needs of pupils from pre-5 to 19 years with moderate, severe and profound learning difficulties, autistic spectrum disorders, complex and multiple disabilities and associated emotional and behavioural difficulties. Standing in the School grounds is Ardlui House which provides residential short breaks for up to 2 weeks for the same types of children and young people.

For those parents who wish their children to have a Roman Catholic education provided by Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

, St Joseph's Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

has a partner primary school

A primary school (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and South Africa), junior school (in Australia), elementary school or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary e ...

of the same name based in the Kirkmichael area of the town, with the partner secondary school being the high-achieving Our Lady and St Patrick's High School

Our Lady & St Patrick's High School is a six-year co-educational comprehensive Roman Catholic school, situated in the Bellsmyre area of Dumbarton, Scotland. It is the only denominational secondary school for Dumbarton, the nearby Vale of Leven Co ...

in Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; also sco, Dumbairton; ) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. In 2006, it had an estimated population of 19,990.

Dumbarton was the ca ...

.

Lomond School

Lomond School is an independent, co-educational, day and boarding school in Helensburgh, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Lomond School is, currently, the only day and boarding school on the west coast of Scotland. It was formed from a merger in 1977 b ...

is the only private school in Helensburgh, and hence the only one for which fees have to be paid. The school was founded in 1977 as a result of a merger between St Bride's School (which was for girls) and Larchfield School (which was primary only and for boys).

Both primary and secondary education are provided at Lomond School and the school caters for both day pupils and boarders, with quite a number of the latter coming from abroad.

Medical Services

The town has two medical practices, both located within the same Medical Centre in East King Street. There are also a number of dentists and opticians in the town. Built as the Victoria Infirmary, the Victoria Integrated Care Centre no longer cares for in-patients and the original building is now little used. However a variety of clinics do take place in buildings in the grounds.

The nearest functioning hospital is the Vale of Leven Hospital in

Built as the Victoria Infirmary, the Victoria Integrated Care Centre no longer cares for in-patients and the original building is now little used. However a variety of clinics do take place in buildings in the grounds.

The nearest functioning hospital is the Vale of Leven Hospital in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. However the range of services available there has been reduced, and so local people needing hospital care now often have to travel further afield, and in particular to the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Paisley.

In 2006 the Helensburgh district opted to come within the NHS Highland area, which is based in Inverness. However, because of the great distance between the Helensburgh area and Inverness, NHS Highland has an arrangement with NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde is an NHS board in West Central Scotland, created from the amalgamation of NHS Greater Glasgow and part of NHS Argyll and Clyde on 1 April 2006.

It is the largest health board in both Scotland, and the UK, which c ...

which ensures that the latter provides the services needed locally.

Sport and leisure

Sports are well represented with various football, rugby, cricket, athletics, netball, hockey,

Sports are well represented with various football, rugby, cricket, athletics, netball, hockey, curling

Curling is a sport in which players slide stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area which is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take turns slidi ...

, bowling

Bowling is a target sport and recreational activity in which a player rolls a ball toward pins (in pin bowling) or another target (in target bowling). The term ''bowling'' usually refers to pin bowling (most commonly ten-pin bowling), thou ...

, golf, sailing and fishing clubs amongst others active in the town. The seafront has an indoor swimming pool, an esplanade walk, a range of shops, cafes and pubs, and sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, windsurfer, or kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (land yacht) over a chosen cou ...

facilities including Helensburgh Sailing Club.

Helensburgh is home to a number of annual events, with the local branch of the Round Table running an annual fireworks display

Fireworks are a class of Explosive, low explosive Pyrotechnics, pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a l ...

on Guy Fawkes Night and hosting a Real Ale Festival. Helensburgh & Lomond Highland Games take place annually around the start of June.

In 2015 the former St Columba Church at the corner of Sinclair Street and West King Street became The Tower. This is a digital arts centre which has 2 cinema screens and which also stages a range of live performances. Furthermore, training in various aspects of digital arts is also undertaken.

Walking, cycling and kayaking routes

There are a number of footpaths in and around Helensburgh, and it is also the starting point for some long distance walking and kayaking.

In the town itself there are footpaths inside the Duchess Woods, Argyll & Bute's only local nature reserve. Just outside the town there is an attractive footpath of 2 miles length (3 km) around Ardmore Point.

A longer footpath is the Three Lochs Way which connects

There are a number of footpaths in and around Helensburgh, and it is also the starting point for some long distance walking and kayaking.

In the town itself there are footpaths inside the Duchess Woods, Argyll & Bute's only local nature reserve. Just outside the town there is an attractive footpath of 2 miles length (3 km) around Ardmore Point.

A longer footpath is the Three Lochs Way which connects Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; gd, Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'Richens, R. J. (1984) ''Elm'', Cambridge University Press.) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of C ...

with Helensburgh, the Gareloch and Loch Long, and which runs for 34 miles (55 km).

The longest by far of all the walks with a local start is the John Muir Way

The John Muir Way is a continuous long-distance route in southern Scotland, running from Helensburgh, Argyll and Bute in the west to Dunbar, East Lothian in the east. It is named in honour of the Scottish conservationist John Muir, who was ...

. This commemorates John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist ...

who is celebrated worldwide as the "Father of National Parks" and runs from Helensburgh for 134 miles (215 km) to his birthplace at Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and gave its name to an ecc ...

in East Lothian.

The Clyde Sea Lochs Trail is a road route from Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; also sco, Dumbairton; ) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. In 2006, it had an estimated population of 19,990.

Dumbarton was the ca ...

, through Helensburgh, round the Rosneath Peninsula, and ending at Arrochar, with information panels along the way. The quieter parts of the route will be of interest to cyclists, while geocaching can also be carried out.

The Argyll Sea Kayak Trail also starts at Helensburgh pier and passes through some of Scotland's finest coastal scenery for around 95 miles (150 km), finishing at Oban.

Recent developments

Major changes have taken place within the town centre in the years leading up to 2016, and others are due to take place within the next 5 years, see " #Future Developments" below for fuller details. A major upgrade to the streets in the town centre has taken place. Pavements have been widened and attractive new surfaces of

A major upgrade to the streets in the town centre has taken place. Pavements have been widened and attractive new surfaces of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

have replaced tarmac and concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

. This has occurred most notably in Colquhoun Square where parts of Colquhoun Street have been blocked off, thus creating an area of open space which is available for events including festivals and farmers markets. In particular the award-winning Outdoor Museum has been established in the Square, see " #Miscellany" below for fuller details. Likewise improvements have been made to some of the other streets within the town centre and to the portion of the West Esplanade which lies within the town centre.

Clyde Street School at 38 East Clyde Street was opened in 1904 to the design of local architect A N Paterson. In 1967 it ceased to function as a school, becoming instead a Community Education Centre. This was closed in 2004 and for a long while as the building lay derelict. However, in 2015 it reopened as the Helensburgh and Lomond Civic Centre of Argyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

; not only was the old school given a most attractive renovation, but a substantial modern wing was added to it. There is a public cafe in the old school section, and displays from the collections of Helensburgh Heritage Trust can also be seen there.

The Tower Digital Arts Centre, housed in the former St Columba Church on Sinclair Street, was converted into a first release double screen cinema and arts centre for the town.

The West King Street Hall next door was converted and took on a new role in 2018 as the Scottish Submarine Centre. The Centre now houses the last (1955) Stickleback-class submarine built for the Royal Navy.

Future developments

The swimming pool on Helensburgh pierhead stands on an area of land which has been reclaimed from the sea, but unfortunately it can be under water in gales. In 2020 work started on a new swimming pool; it is due to be finished in 2022 after whichArgyll and Bute Council

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020). ...

will demolish the old swimming pool. The area of reclaimed land has been raised, and there may also be some minor commercial development there.

Work started in February 2017 on a major renovation of Hermitage Park which will cost over £3 million and which will be complete by the end of 2020. The Park Pavilion is a Passivhaus design, believed to be the first non-domestic Passivhaus building in Scotland.

Miscellany

Twin town

Helensburgh's only twin town isThouars

Thouars () is a commune in the Deux-Sèvres department in western France. On 1 January 2019, the former communes Mauzé-Thouarsais, Missé and Sainte-Radegonde were merged into Thouars.

It is on the River Thouet. Its inhabitants are known ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. A twinning agreement was signed in 1983.

Helensburgh, Australia

Helensburgh

Helensburgh (; gd, Baile Eilidh) is an affluent coastal town on the north side of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire, it became part of Argyll and Bute following local gove ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia was originally known as Camp Creek. When the Illawarra railway line

The South Coast Railway (also known as the Illawarra Railway) is a commuter and goods railway line from Sydney to Wollongong and Bomaderry in New South Wales, Australia. Beginning at the Illawarra Junction, the line services the Illawarra a ...

was being built in the area, coal was discovered, and so the township originally developed for coal mining.

The name of the place was changed to Helensburgh in 1888 by Charles Harper who had become the first manager of the coalmine in 1886. It is believed in Australia that he was born in Helensburgh, Scotland in 1835. He also called his daughter Helen, and so it is possible that the town in Australia is actually named after her. In the same year as Helensburgh in Australia acquired its new name, Charles Harper was killed in a mining accident whilst supervising the haulage of a new steam boiler, a wire rope broke and he was killed in the recoil.

Helensburgh, New Zealand

Helensburgh, New Zealand is a suburb ofDunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

. How it acquired its name is something of a mystery. According to one of a series of articles in the ''Evening Star'' newspaper in 1959 about the origins of Dunedin street names, the area once belonged to Miss Helen Hood. The locality was originally called Helensburn, but unofficial local opinion is that it turned into Helensburgh because at least some of the local population who were from Scotland thought that that was what the name should be.

The Baronetcy of Helensburgh

The Raeburn Baronetcy of Helensburgh in the County of Dunbarton, is a title in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 25 July 1923 byKing George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

for William Raeburn. He was head of the firm of Raeburn & Verel Ltd, a shipping company whose ships constituted the Monarch Steamship Company. His obituary in the ''Helensburgh & Gareloch Times'' describes how he was involved in various aspects of the shipping industry and how "in 1916 he was appointed President of the Chamber of Shipping by the shipowners of the United Kingdom".

On his retirement from that post he was awarded with a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

. He also represented Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders Pe ...

in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

as a Unionist from 1918 until the General Election in December 1923 and so it was towards the end of his political career that the Baronetcy of Helensburgh was created for him. He died on 12 February 1934 at the age of 83, having come to live in the town towards the end of the 19th century. During his life he had been a Justice of the Peace and had also been involved with many local organisations.

The Outdoor Museum

When Colquhoun Square was redesigned in 2015 an integral part of its new look was the Outdoor Museum. Around 120 plinths have been erected in the Square, largely as a means of directing the little traffic which is allowed there. The long-term aim is that these plinths will gradually be filled over the years with items or replicas of items connected with Helensburgh's history and character. So far around 15 plinths now have an assortment of artefacts or artworks on them. The plinths themselves have been engraved with both a description of the items and QR codes which can be scanned for more information. Those on display to date are a very diverse collection and include a puppet's head used byJohn Logie Baird

John Logie Baird FRSE (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first live working television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the first publicly dem ...

in his first television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

experiments, the ship's bell from Henry Bell's paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses we ...

''Comet'', miniature shoes and butter pats (for shaping butter). In addition a number of brass plaques have been set into the pavements and these give a description of the condition of the streets of the town in 1845.

WAVEparticle was the designer of the Outdoor Museum, and the concept has been given a number of awards.

Notable people

Henry Bell

Henry Bell (1767–1830) was born inTorphichen

Torphichen ( ) is a historic small village located north of Bathgate in West Lothian, Scotland. The village is approximately 18 miles (20 km) west of Edinburgh, 7 miles (11 km) south-east of Falkirk and 4 miles (6 km) south-west of Linlithgow. ...

in West Lothian and only came to Helensburgh when he was around 30 years old. However he remained in the town for the rest of his life and he was the first recorded Provost of Helensburgh. He is famous for introducing the paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses we ...

''Comet'', see " #Henry Bell and the ''Comet''" above for fuller details. He is buried in Rhu churchyard.

John Logie Baird

Of the three most famous residents of Helensburgh, the only one to have been born in the town was

Of the three most famous residents of Helensburgh, the only one to have been born in the town was John Logie Baird

John Logie Baird FRSE (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first live working television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the first publicly dem ...

(1888–1946). He was the first man in the world ever to transmit proper television pictures and in his day he was recognised as the inventor of television. His success was acknowledged in ''The Radio News'' of America in September 1926: "Mr Baird has definitely and indisputably given a demonstration of real television. It is the first time in history that this has been done in any part of the world."

This was seven months before AT&T

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile te ...

made their first transmission within the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

which was erroneously claimed in one American headline as "Television at Last". Because Baird used an electro-mechanical system there are still those who merely describe him as a television pioneer rather than the inventor of television.

He also made the world's first video recordings (on 78 rpm gramophone records

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English), or simply a record, is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts near ...

) and produced an infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from around ...

night sight which incorporated a major development in the field of fibreoptics.

Over 24 years he was granted 177 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

s.

At the age of two he had suffered a major illness which left his health seriously impaired; every winter he would have a severe cold or chest infection, with the result that, when he volunteered for the Armed Forces during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he was deemed to be unfit for any form of military service. Baird left Helensburgh about the time when he became a student, and he subsequently spent most of his life in the south of England, where he died. However he is buried in Helensburgh Cemetery.

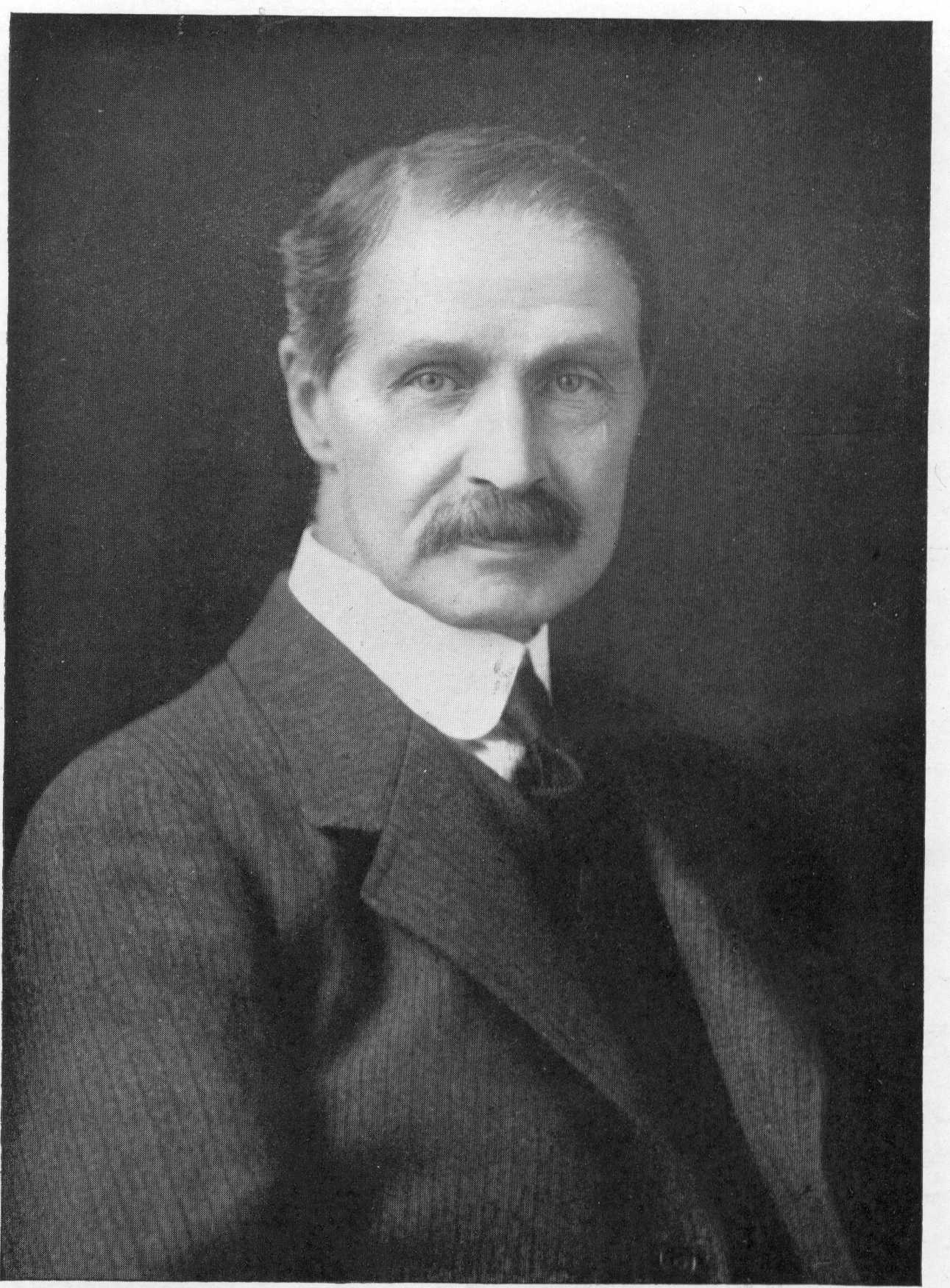

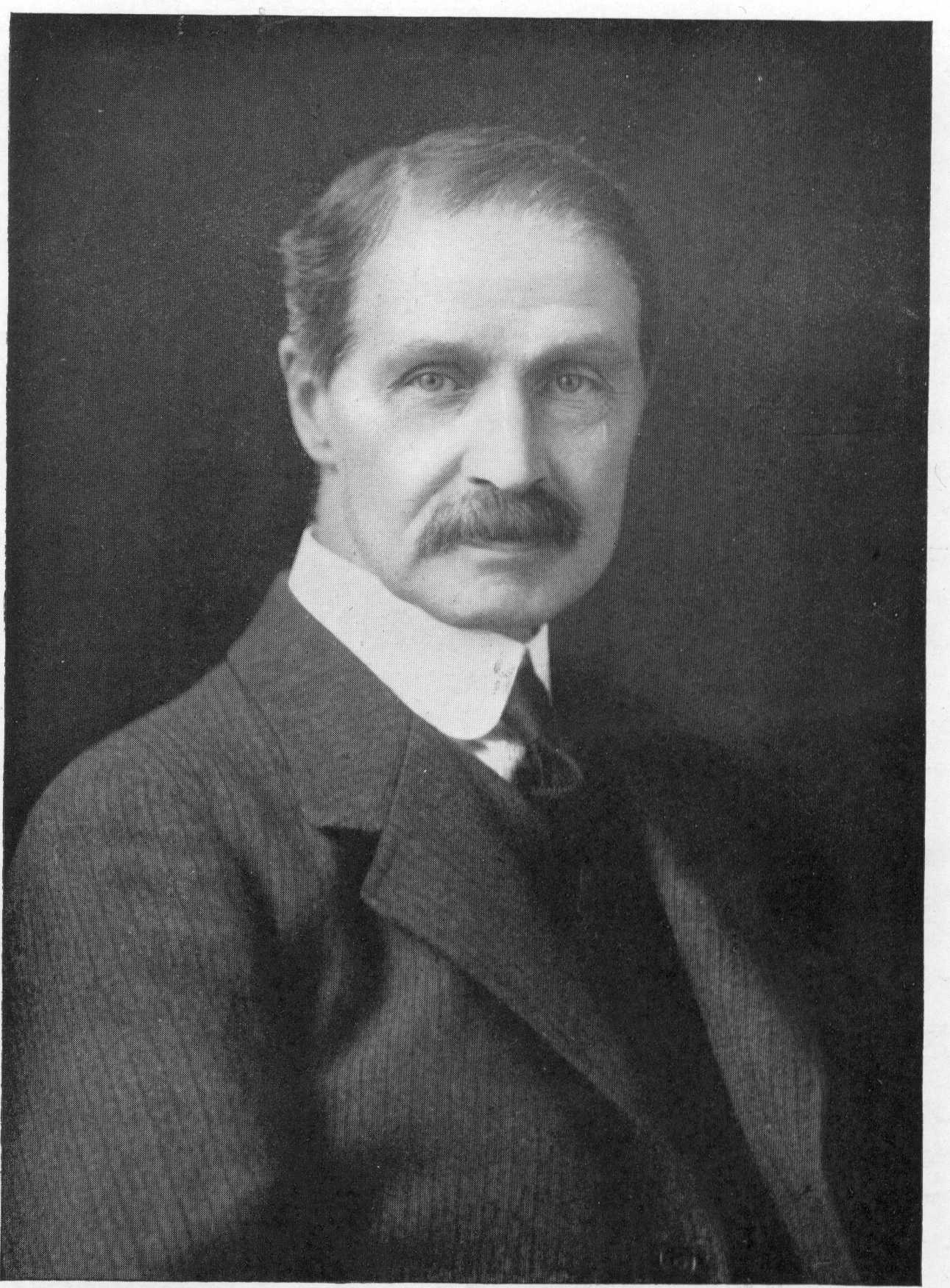

Bonar Law

Future British

Future British Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Bonar Law resided in Helensburgh from the age of 12, following the death of his mother and his father remarrying in his native Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. He lived with relatives, the Kidstons, in the town and later entered the iron trade in Glasgow.

He was elected as a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) in Glasgow and served as Chancellor of the Exchequer during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was invited to become Prime Minister by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, deferring in favour of David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

and serving in his coalition government. In 1922, he became Prime Minister, serving for six months before resigning following a diagnosis of throat cancer

Head and neck cancer develops from tissues in the lip and oral cavity (mouth), larynx (throat), salivary glands, nose, sinuses or the skin of the face. The most common types of head and neck cancers occur in the lip, mouth, and larynx. Symptoms ...

and dying in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

six months later. Law was later described by H. H. Asquith, another former Prime Minister, as "the unknown Prime Minister".

His wife had predeceased him in 1909 and is buried in Helensburgh Cemetery. Despite his wishes to be buried alongside her, his family were persuaded to have his ashes buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

. He and his wife are commemorated in a window in Helensburgh Parish Church, as are also two of their sons who died in the First World War.

Although he became known as "the unknown Prime Minister", he reached an office which less than a hundred people every century manage to reach, and so he richly deserves to be known as one of Helensburgh's most famous residents.

Other notable residents

* Martin Alabaster,Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

officer

*Gavin Arneil

Gavin Cranston Arneil (7 March 1923 – 21 January 2018) was a Scottish paediatric nephrologist. At the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Glasgow, he established the first specialised unit in Britain for children with kidney disease.

Biograph ...

, doctor, paediatric nephrologist

* Phil Ashby, Royal Marines Commando

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

officer

*W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, poet

*William Auld

William Auld (6 November 1924 – 11 September 2006) was a British poet, author, translator and magazine editor who wrote chiefly in Esperanto.

Life

Auld was born at Erith in Kent, and then moved to Glasgow with his parents, attending Alla ...

, poet and author

*Marco Biagi Marco Biagi can refer to:

* Marco Biagi (jurist) (1950–2002), Italian jurist

* Marco Biagi (politician)

Marco Biagi (born 31 July 1982) is a Scottish National Party (SNP) politician. He served as the Minister for Local Government and Commun ...

, politician

* John Black, football player

* Bobby Blair, football player

* James Bridie, playwright and screenwriter

*Bobby Brown

Robert Barisford Brown (born February 5, 1969) is an American singer, songwriter and dancer. Brown, alongside frequent collaborator Teddy Riley, is noted as one of the pioneers of new jack swing: a fusion of hip hop and R&B. Brown started h ...

, football player and manager

*Jack Buchanan

Walter John Buchanan (2 April 1891 – 20 October 1957) was a Scottish theatre and film actor, singer, dancer, producer and director. He was known for three decades as the embodiment of the debonair man-about-town in the tradition of George G ...

, actor, singer, producer and director

* John Buchanan, Olympic Gold medal-winning sailor