Caproni Ca.60 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

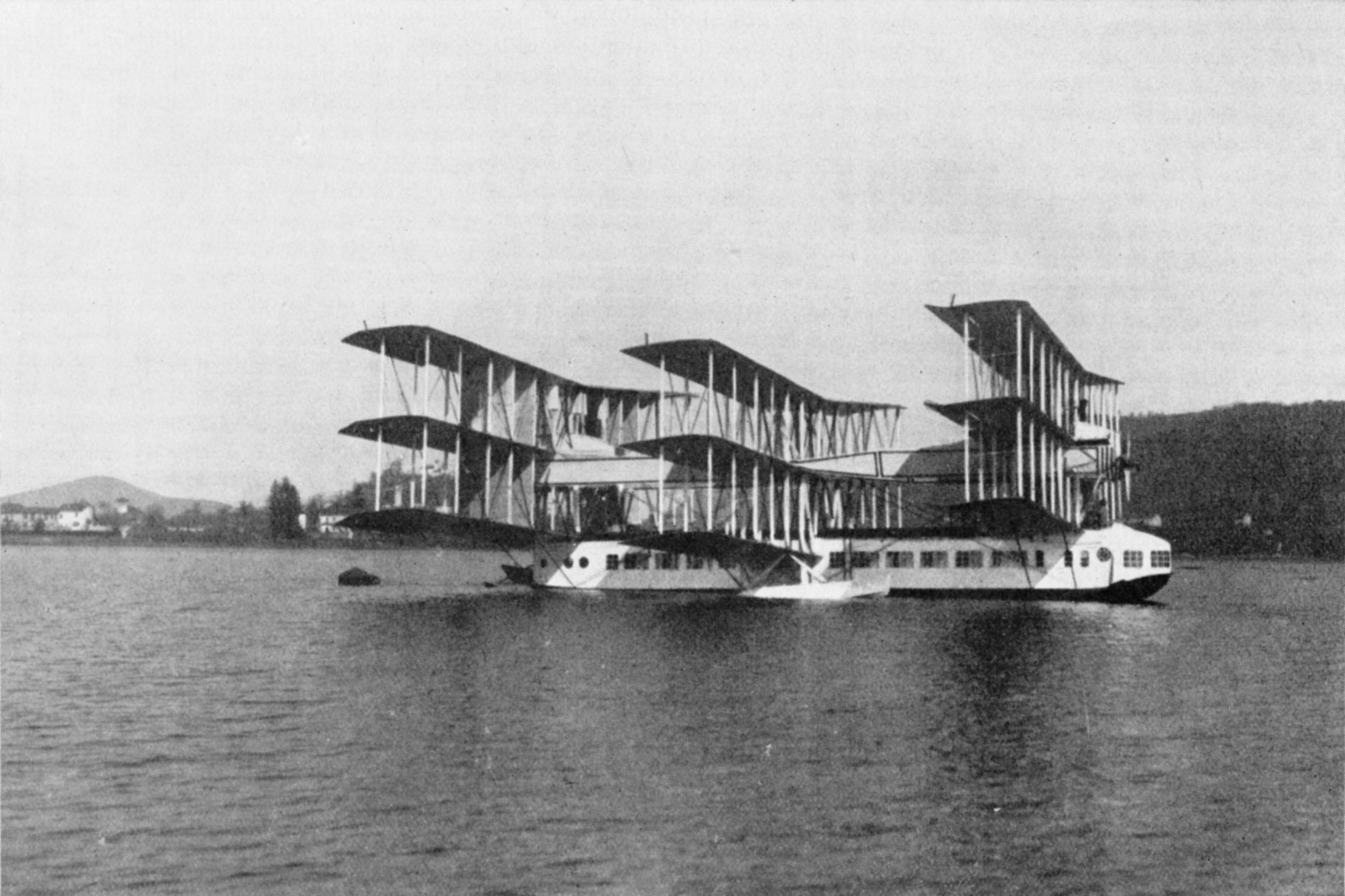

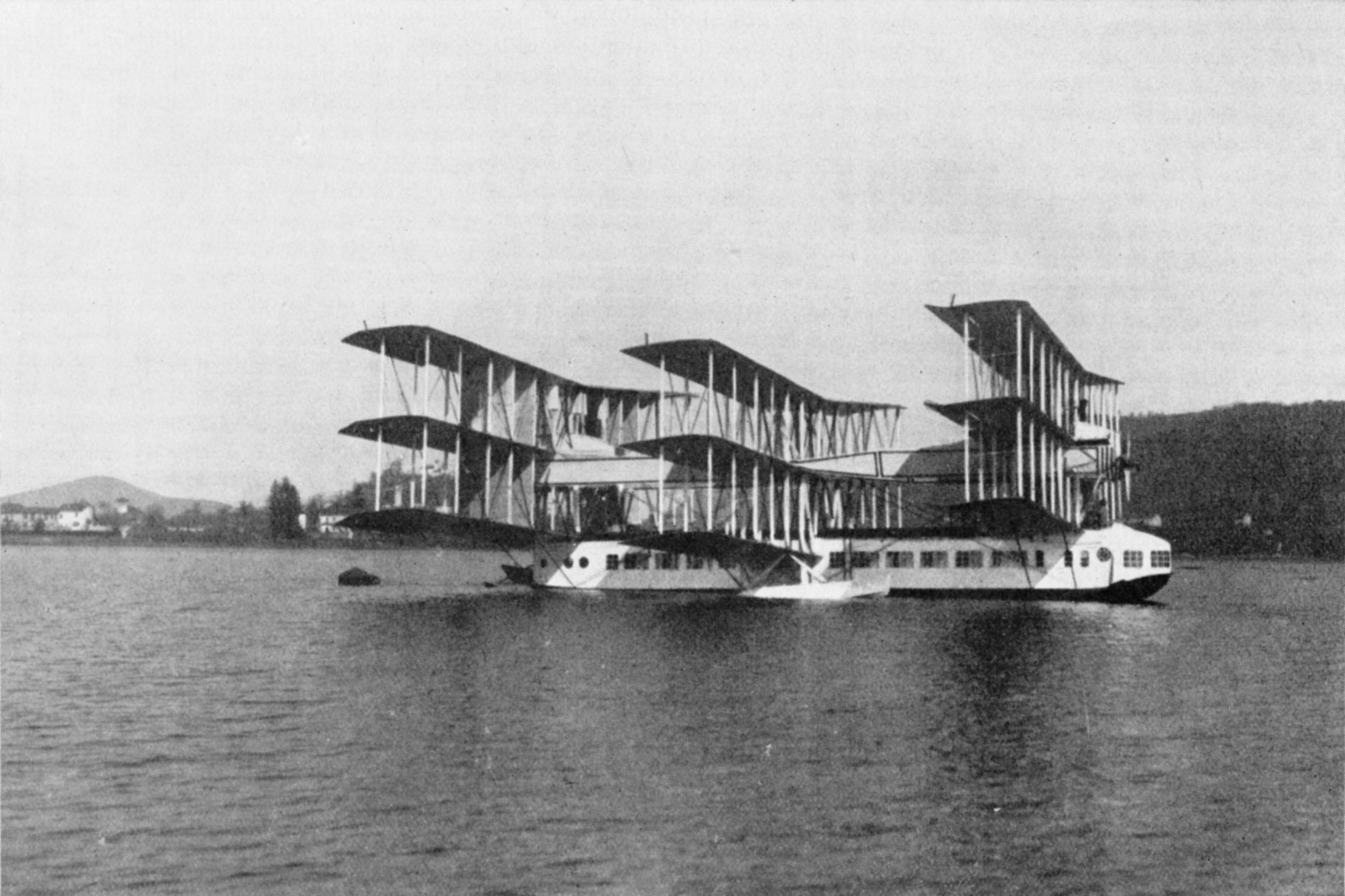

The Caproni Ca.60 Transaereo, often referred to as the Noviplano (nine-wing) or Capronissimo, was the prototype of a large nine-wing flying boat intended to become a 100-passenger transatlantic airliner. It featured eight engines and three sets of triple wings.

Only one example of this aircraft, designed by

The construction of the model 3000, or Transaereo, began in the second half of 1919. The earliest reference to this event is found in a French daily newspaper of August 10, 1919, and perhaps the first parts were built in the Caproni factory of

The construction of the model 3000, or Transaereo, began in the second half of 1919. The earliest reference to this event is found in a French daily newspaper of August 10, 1919, and perhaps the first parts were built in the Caproni factory of

The aircraft was powered by eight Liberty L-12

The aircraft was powered by eight Liberty L-12  The

The

Always keeping on the water surface, the aircraft made some turns, then accelerated simulating a takeoff run, then made other maneuvers in front of Gianni Caproni and other important representatives of the Italian aviation in the 1920s:

Always keeping on the water surface, the aircraft made some turns, then accelerated simulating a takeoff run, then made other maneuvers in front of Gianni Caproni and other important representatives of the Italian aviation in the 1920s:  On the next day, after reconsidering some of his calculations, Caproni decided to load the bow of the Transaereo with

On the next day, after reconsidering some of his calculations, Caproni decided to load the bow of the Transaereo with  Caproni, coming from Vizzola Ticino by automobile, was delayed, and only arrived on the shore of Lake Maggiore after the Transaereo had crashed. He later commented, "So the fruit of years of work, an aircraft that was to form the basis of future aviation, all is lost in a moment. But one must not be shocked if one wants to progress. The path of progress is strewn with suffering."

At the time, the accident was blamed on two concurrent causes. First, the wake of a steamboat that was navigating on the lake close to the area where the Transaereo was accelerating was thought to have interfered with the takeoff. Second, test pilot Semprini was blamed for having kept pulling the yoke trying to gain altitude while he should have performed corrective maneuvers, for example lowering the nose to let the huge aircraft gain speed. Another theory suggests the aforementioned boat was a ferry loaded with passengers and Semprini (who was only performing some taxiing trials, for he did not mean to take off before Caproni's arrival on the spot) was suddenly compelled to take off, in spite of the insufficient speed, to avoid a collision. According to more recent theories, the cause of the accident was probably the sandbags that had been placed in the aircraft to simulate the weight of passengers: not having been fastened to the seats, they may have slid to the back of the fuselage when, upon takeoff, the Transaereo suddenly pitched up. With the tail burdened by this additional load and a shift in the

Caproni, coming from Vizzola Ticino by automobile, was delayed, and only arrived on the shore of Lake Maggiore after the Transaereo had crashed. He later commented, "So the fruit of years of work, an aircraft that was to form the basis of future aviation, all is lost in a moment. But one must not be shocked if one wants to progress. The path of progress is strewn with suffering."

At the time, the accident was blamed on two concurrent causes. First, the wake of a steamboat that was navigating on the lake close to the area where the Transaereo was accelerating was thought to have interfered with the takeoff. Second, test pilot Semprini was blamed for having kept pulling the yoke trying to gain altitude while he should have performed corrective maneuvers, for example lowering the nose to let the huge aircraft gain speed. Another theory suggests the aforementioned boat was a ferry loaded with passengers and Semprini (who was only performing some taxiing trials, for he did not mean to take off before Caproni's arrival on the spot) was suddenly compelled to take off, in spite of the insufficient speed, to avoid a collision. According to more recent theories, the cause of the accident was probably the sandbags that had been placed in the aircraft to simulate the weight of passengers: not having been fastened to the seats, they may have slid to the back of the fuselage when, upon takeoff, the Transaereo suddenly pitched up. With the tail burdened by this additional load and a shift in the

Because the photographer was on board the same car as Caproni, no photos exist of the takeoff, flight or crash, but many were shot of the wreck.

The flying boat had sustained heavy damage in the crash, but the rear two-thirds of the fuselage and the central and aft wing sets were almost intact. However, the Transaereo had to be towed to shore. The crossing of the lake, performed thanks to a boat that may have been the same that had interfered with the takeoff, further damaged the aircraft: a considerable quantity of water leaked in the hull and the fuselage was partly submerged, while the central and aft wing sets got damaged and partly collapsed in the water.

The possibility of repairing the Transaereo was remote. After the accident, only the metallic parts and the engines were still usable. Almost all wooden parts would have to be rebuilt. The cost of the repairs, according to Caproni's own estimate, would be one-third of the total cost of building the prototype, but he doubted the company's resources would be sufficient to sustain such a financial effort. After initial discouragement, however, on March 6 Caproni was already considering design modifications to carry on the project of a 100-passenger transatlantic flying boat. He was sure that the Transaereo was a promising machine, and decided to build a 1/4 scale model to keep on testing the concept.

After discussing with De Siebert and

Because the photographer was on board the same car as Caproni, no photos exist of the takeoff, flight or crash, but many were shot of the wreck.

The flying boat had sustained heavy damage in the crash, but the rear two-thirds of the fuselage and the central and aft wing sets were almost intact. However, the Transaereo had to be towed to shore. The crossing of the lake, performed thanks to a boat that may have been the same that had interfered with the takeoff, further damaged the aircraft: a considerable quantity of water leaked in the hull and the fuselage was partly submerged, while the central and aft wing sets got damaged and partly collapsed in the water.

The possibility of repairing the Transaereo was remote. After the accident, only the metallic parts and the engines were still usable. Almost all wooden parts would have to be rebuilt. The cost of the repairs, according to Caproni's own estimate, would be one-third of the total cost of building the prototype, but he doubted the company's resources would be sufficient to sustain such a financial effort. After initial discouragement, however, on March 6 Caproni was already considering design modifications to carry on the project of a 100-passenger transatlantic flying boat. He was sure that the Transaereo was a promising machine, and decided to build a 1/4 scale model to keep on testing the concept.

After discussing with De Siebert and

Period documentary about the Transaereo

(static display) {{Caproni aircraft 1920s Italian airliners Flying boats Ca.060 Triplanes Tandem-wing aircraft Multiplane aircraft Eight-engined push-pull aircraft Aircraft first flown in 1921

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

aviation pioneer

Aviation pioneers are people directly and indirectly responsible for the advancement of flight, including people who worked to achieve manned flight before the invention of aircraft, as well as others who achieved significant "firsts" in aviation a ...

Gianni Caproni

Giovanni Battista Caproni, 1st Count of Taliedo (July 3, 1886 – October 27, 1957), known as "Gianni" Caproni, was an Italian aeronautical engineer, civil engineer, electrical engineer, and aircraft designer who founded the Caproni aircraft-m ...

, was built by the Caproni

Caproni, also known as ''Società de Agostini e Caproni'' and ''Società Caproni e Comitti'', was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Its main base of operations was at Taliedo, near Linate Airport, on the outskirts of Milan.

Founded by Giovan ...

company. It was tested on Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore (, ; it, Lago Maggiore ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh Maggior; pms, Lagh Magior; literally 'Greater Lake') or Verbano (; la, Lacus Verbanus) is a large lake located on the south side of the Alps. It is the second largest l ...

in 1921: its brief maiden flight took place on February 12 or March 2. Its second flight was March 4; shortly after takeoff, the aircraft crashed on the water surface and broke up upon impact. The Ca.60 was further damaged when the wreck was towed to shore and, in spite of Caproni's intention to rebuild the aircraft, the project was soon abandoned because of its excessive cost. The few surviving parts are on display at the Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics

The Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics (Italian: ''Museo dell'Aeronautica Gianni Caproni'') is Italy's oldest aviation museum, as well as the country's oldest corporate museum. It was established in 1927 as the Caproni Museum (''Museo Caproni'') ...

and at the Volandia

Volandia Park and Flight Museum is the largest Italian aeronautical museum, as well as one of the largest in Europe. Volandia displays over 100 aircraft. The museum covers an area of ca. 60,000 m2 (645,000 sq ft) of which 20,000 m2 (215,000 sq f ...

aviation museum in Italy.

Development

Gianni Caproni

Giovanni Battista Caproni, 1st Count of Taliedo (July 3, 1886 – October 27, 1957), known as "Gianni" Caproni, was an Italian aeronautical engineer, civil engineer, electrical engineer, and aircraft designer who founded the Caproni aircraft-m ...

became a famous aircraft designer and manufacturer during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; his Caproni

Caproni, also known as ''Società de Agostini e Caproni'' and ''Società Caproni e Comitti'', was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Its main base of operations was at Taliedo, near Linate Airport, on the outskirts of Milan.

Founded by Giovan ...

aviation company had major success, especially in the field of heavy multi-engine bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

s, building aircraft such as the Caproni Ca.32, Ca.33, Ca.36 and Ca.40. The end of the conflict, however, caused a dramatic decrease in the demand for bombers in the Italian military. As a result, Caproni, like many other entrepreneurs of the time, directed his attention to the civil aviation market.

As early as 1913 Caproni, then aged 27, had said during an interview for the Italian sports newspaper '' La Gazzetta dello Sport'' that "aircraft with a capacity of one hundred and more passengers" would soon become a reality. It was after the war, however, that (besides converting some of his large wartime bombers into airliners) Caproni began designing a huge and ambitious passenger flying boat; he first took out a patent on a design of this kind on February 6, 1919.

The idea of a large multi-engined flying boat designed for carrying passengers on long-range flights was considered, at the time, rather eccentric. Caproni thought, however, that such an aircraft could allow the travel to remote areas more quickly than ground or water transport, and that investing in innovative aerial means would be a less expensive strategy than improving traditional thoroughfares. He affirmed that his large flying boat could be used on any route, within a nation or internationally, and he considered operating it in countries with large territories and poor transport infrastructures, such as China.

Caproni believed that, to attain these objectives, rearranging wartime aircraft would not be sufficient. On the contrary, he thought that a new generation of airliners (featuring extended range and increased payload capacity, the latter in turn allowing a reduction in cost per passenger) had to supersede the converted leftovers from the war.

In spite of criticism from some important figures in Italian aviation, especially aerial warfare theorist Giulio Douhet

General Giulio Douhet (30 May 1869 – 15 February 1930) was an Italian general and air power theorist. He was a key proponent of strategic bombing in aerial warfare. He was a contemporary of the 1920s air warfare advocates Walther Wever, Billy ...

, Caproni started designing a very innovative aircraft and soon, in 1919, he took out a patent on it.

Caproni was aware of the safety

Safety is the state of being "safe", the condition of being protected from harm or other danger. Safety can also refer to the control of recognized hazards in order to achieve an acceptable level of risk.

Meanings

There are two slightly dif ...

problems connected to passenger flights, such concerns being the root of Douhet's criticism. So, he concentrated on both improving the aircraft's reliability and minimizing the damage that could be caused by possible accidents. First of all, he conceived his large seaplane as a multi-engine aircraft featuring enough motors to allow it to keep flying even in case of the failure of one or more of them. He also considered (but then discarded) the opportunity of providing the aircraft with "backup engines" that could be shut off once the cruise altitude had been reached and only restarted in case of emergency. The seaplane configuration assured the capability of performing relatively safe and easy emergency

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worsening ...

water landing

In aviation, a water landing is, in the broadest sense, an aircraft landing on a body of water. Seaplanes, such as floatplanes and flying boats, land on water as a normal operation. Ditching is a controlled emergency landing on the water s ...

s on virtually any water surface calm and large enough. Moreover, Caproni intended to improve the comfort of the passengers by increasing the cruise altitude, which he meant to achieve with turbocharger

In an internal combustion engine, a turbocharger (often called a turbo) is a forced induction device that is powered by the flow of exhaust gases. It uses this energy to compress the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to pro ...

s and variable-pitch propellers (such devices could compensate for the loss of power output of the engines at high altitude).

The construction of the model 3000, or Transaereo, began in the second half of 1919. The earliest reference to this event is found in a French daily newspaper of August 10, 1919, and perhaps the first parts were built in the Caproni factory of

The construction of the model 3000, or Transaereo, began in the second half of 1919. The earliest reference to this event is found in a French daily newspaper of August 10, 1919, and perhaps the first parts were built in the Caproni factory of Vizzola Ticino

Vizzola Ticino is a village and ''comune'' of the province of Varese in Lombardy, Italy. It is on the banks of the Ticino River, immediately to the west of Strada Provinciale 52 on the western perimeter of Malpensa Airport.

In the late 19th ce ...

. In September an air fair took place at the Caproni factory in Taliedo

Taliedo is a peripheral district ("quartiere") of the city Milan, Italy, part of the Zone 4 administrative division, located south-east of the city centre. The informal boundaries of the district are three main city streets, respectively Via Mecen ...

, not far from Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, during which the new, ambitious project was heavily publicized. Later in September, Caproni experimented with a Caproni Ca.4 seaplane to improve his calculations for the Transaereo. In 1920, the huge hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

where most of the construction of the Transaereo was to take place was built in Sesto Calende

Sesto Calende is a town and ''comune'' located in the province of Varese, in the Lombardy region of northern Italy.

It is at the southern tip of Lake Maggiore, where the Ticino River starts to flow towards the Po River. The main historical sight ...

, on the shore of Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore (, ; it, Lago Maggiore ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh Maggior; pms, Lagh Magior; literally 'Greater Lake') or Verbano (; la, Lacus Verbanus) is a large lake located on the south side of the Alps. It is the second largest l ...

. The several parts built by Caproni's subcontractors, many of whom had already collaborated with the company during the Great War, were assembled here.

At the end of the year, the construction yard was visited by United States Ambassador to Italy

Since 1840, the United States has had diplomatic representation in the Italian Republic and its predecessor nation, the Kingdom of Italy, with a break in relations from 1941 to 1944 while Italy and the U.S. were at war during World War II. The U. ...

Robert Underwood Johnson

Robert Underwood Johnson (January 12, 1853 – October 14, 1937) was an American writer, poet, and diplomat.

Biography

Robert Underwood Johnson was born in Centerville, Indiana, on January 12, 1853. His brother Henry Underwood Johnson b ...

, who admired Caproni's exceptional aircraft. The press affirmed that the aircraft would be able to begin test flights in January 1921, and added that, were the tests successful, Italy would swiftly gain international supremacy in the field of civil aerial transport.

On January 10, 1921 the forward engines and nacelles were tested, and no dangerous vibrations were recorded. On January 12 two of the aft engines were also successfully tested. On the fifteenth, Caproni forwarded his request for permission to undertake test flights to the Inspector General of Aeronautics, General Omodeo De Siebert.

Design

The Transaereo was a large flying boat, whose main hull, which contained the cabin, hung below three sets ofwing

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is e ...

s in tandem

Tandem, or in tandem, is an arrangement in which a team of machines, animals or people are lined up one behind another, all facing in the same direction.

The original use of the term in English was in ''tandem harness'', which is used for two ...

, each composed of three superimposed aerodynamic surfaces: one set was located fore of the hull, one aft and one in the center (a little lower than the other two). The wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan o ...

of each of the nine wings was 30 m (98 ft 5 in), and the total wing area was 750.00 m² (8073 ft²); the fuselage was 23.45 m (77 ft) long and the whole structure, from the bottom of the hull to the top of the wings, was 9.15 m (30 ft) high. The empty weight The empty weight of a vehicle is based on its weight without any payload (cargo, passengers, usable fuel, etc.).

Aviation

Many different empty weight definitions exist. Here are some of the more common ones used.

GAMA standardization

In 1975 ...

was 14,000 kg (30,865 lb) and the maximum takeoff weight

The maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) or maximum gross takeoff weight (MGTOW) or maximum takeoff mass (MTOM) of an aircraft is the maximum weight at which the pilot is allowed to attempt to take off, due to structural or other limits. The analogous ...

was 26,000 kg (57,320 lb).

Lifting and control surfaces

Each set of three wings was obtained by the direct reuse of the lifting surfaces of the triplane bomber Caproni Ca.4; after the end of the war several aircraft of this type were cannibalized in order to build the Transaereo. Theflight control system

A conventional fixed-wing aircraft flight control system consists of flight control surfaces, the respective cockpit controls, connecting linkages, and the necessary operating mechanisms to control an aircraft's direction in flight. Aircraft ...

was composed of ailerons (fitted on each single wing) and rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

s, even if the aircraft didn't have a tail assembly in the traditional sense and, in particular, didn't have a horizontal stabilizer. Roll

Roll or Rolls may refer to:

Movement about the longitudinal axis

* Roll angle (or roll rotation), one of the 3 angular degrees of freedom of any stiff body (for example a vehicle), describing motion about the longitudinal axis

** Roll (aviation) ...

(the aircraft's rotation about the longitudinal axis) was controlled in a completely conventional way by the differential action of port and starboard ailerons; pitch (the aircraft's rotation about the transverse axis) was controlled by the differential action of fore and aft ailerons, since the aircraft didn't have elevators

An elevator or lift is a cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or decks of a building, vessel, or other structure. They are ...

; four articulated vertical surfaces located between the wings of the aftmost wing set acted as vertical stabilizer

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, s ...

s and rudders controlling the yaw (the aircraft's rotation about the vertical axis). Wings had a positive dihedral angle

A dihedral angle is the angle between two intersecting planes or half-planes. In chemistry, it is the clockwise angle between half-planes through two sets of three atoms, having two atoms in common. In solid geometry, it is defined as the un ...

, which contributed to stabilizing the aircraft on the roll axis; Caproni also expected the Transaereo to be very stable on the pitch axis because of the tandem-triplane configuration, for the aft wing set was supposed to act as a very big and efficient stabilizer; he said that the huge aircraft could "be flown with just one hand on the controls." Caproni had patented this particular control system on September 25, 1918.

Propulsion

V12 engine

A V12 engine is a twelve-cylinder piston engine where two banks of six cylinders are arranged in a V configuration around a common crankshaft. V12 engines are more common than V10 engines. However, they are less common than V8 engines.

The f ...

s built in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. Capable of producing 400 hp (294 kW) each, they were the most powerful engines produced during the First World War.

They were arranged in two groups of four engines each: One group at the foremost wing set, and one at the aftmost wing set. Each group featured a central nacelle, containing two engines in a push-pull configuration

An aircraft constructed with a push-pull configuration has a combination of forward-mounted tractor (pull) propellers, and backward-mounted ( pusher) propellers.

Historical

The earliest known examples of "push-pull" engined-layout aircraft incl ...

, all with four-blade propellers

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

. To either side were single-engine nacelles, with two-blade propellers. In the forward engine group, these were pulling, while in the aft engine group, they were pushing.

All nacelles had radiators for the cooling liquid

A coolant is a substance, typically liquid, that is used to reduce or regulate the temperature of a system. An ideal coolant has high thermal capacity, low viscosity, is low-cost, non-toxic, chemically inert and neither causes nor promotes corrosi ...

. Each of the two fore side engines was connected to the central wing set and to the corresponding aft engine thanks to a truss boom with a triangular section.

The two central nacelles also housed an open-air cockpit, for one flight engineer each, who controlled the power output of the engines in response to the orders given by the pilots via means of a complex system of lights and indicators located on electrical panels.

fuel tank

A fuel tank (also called a petrol tank or gas tank) is a safe container for flammable fluids. Though any storage tank for fuel may be so called, the term is typically applied to part of an engine system in which the fuel is stored and propelle ...

s were located in the cabin roof, close to the central wing set. Fuel reached the engines thanks to wind-driven fuel pump

A fuel pump is a component in motor vehicles that transfers liquid from the fuel tank to the carburetor or fuel injector of the internal combustion engine.

Carbureted engines often use low pressure mechanical pumps that are mounted outside the f ...

s.

Hulls

The main fuselage ran the entire length of the plane, below most of the wing structure. The passenger cabin was enclosed, and featured wide panoramic windows. Travelers were meant tosit

Sit commonly refers to sitting.

Sit, SIT or Sitting may also refer to:

Places

* Sit (island), Croatia

* Sit, Bashagard, a village in Hormozgan Province, Iran

* Sit, Gafr and Parmon, a village in Hormozgan Province, Iran

* Sit, Minab, a villa ...

in pairs on wooden benches that faced each other—two facing forward and two backwards. It featured a lavatory

Lavatory, Lav, or Lavvy may refer to:

*Toilet, the plumbing fixture

*Toilet (room), containing a toilet

*Public toilet

*Aircraft lavatory, the public toilet on an aircraft

*Latrine, a rudimentary toilet

*A lavatorium, the washing facility in a mon ...

at the rear end of the fuselage.

An open-air cockpit was positioned above and slightly behind the forward windows. It accommodated a pilot in command

The pilot in command (PIC) of an aircraft is the person aboard the aircraft who is ultimately responsible for its operation and safety during flight. This would be the captain in a typical two- or three- pilot aircrew, or "pilot" if there is on ...

and a co-pilot

In aviation, the first officer (FO), also called co-pilot, is the pilot who is second-in-command of the aircraft to the captain, who is the legal commander. In the event of incapacitation of the captain, the first officer will assume command o ...

side-by-side. Its floor was raised above the passenger cabin floor, so that the shoulders and heads of the pilots protruded through the roof. The flight deck could be reached from inside the fuselage by a ladder.

Besides the main hull, the aircraft was fitted with two side floats located under the central wing set, acting as outriggers

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts ...

which stabilized the aircraft during static floating, takeoff

Takeoff is the phase of flight in which an aerospace vehicle leaves the ground and becomes airborne. For aircraft traveling vertically, this is known as liftoff.

For aircraft that take off horizontally, this usually involves starting with a ...

and landing

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or ...

. Caproni had Alessandro Guidoni, one of the most important seaplane designers of the time, create the hull and floats, the hydrodynamic surfaces that connected them and the two small hydrofoils located close to the nose of the aircraft: Guidoni designed new and innovative floats for the Transaereo to reduce dimensions and weight.

Test flights

The Transaereo was taken out of its hangar for the first time on January 20, 1921, and on that day it was extensively photographed. On January 21, the aircraft was scheduled to be put in the water for the first time, and a cameraman had been hired to shoot some sequences of the aircraft floating on the lake. Because of the low level of the lake and of some difficulties related to the slipway that connected the hangar with the surface of the lake, the flying boat could not reach the water. After receiving De Siebert's authorization, the slipway was lengthened on January 24, and then again on 28. Operations were carried on among problems and obstacles until February 6, when Caproni was informed that 30wing ribs

In an aircraft, ribs are forming elements of the structure of a wing, especially in traditional construction.

By analogy with the anatomical definition of "rib", the ribs attach to the main spar, and by being repeated at frequent intervals, form ...

had broken and needed to be repaired before the beginning of test flights. He was infuriated, and kept his employees awake through the night to allow the tests to begin on February 7. The ribs were fixed, but then a starter was found broken, causing Caproni's frustration, so that the tests had to be postponed again.

On February 9, finally, the Transaereo was put in the water its engines running smoothly and it started taxiing

Taxiing (rarely spelled taxying) is the movement of an aircraft on the ground, under its own power, in contrast to towing or pushback where the aircraft is moved by a tug. The aircraft usually moves on wheels, but the term also includes aircr ...

on the surface of the lake. The pilot was Federico Semprini, a former military flight instructor who was known for having once looped a Caproni Ca.3 heavy bomber. He would be the test pilot in all the subsequent trials of the Transaereo; no tests were going to be performed with more than one pilot on board.

Always keeping on the water surface, the aircraft made some turns, then accelerated simulating a takeoff run, then made other maneuvers in front of Gianni Caproni and other important representatives of the Italian aviation in the 1920s:

Always keeping on the water surface, the aircraft made some turns, then accelerated simulating a takeoff run, then made other maneuvers in front of Gianni Caproni and other important representatives of the Italian aviation in the 1920s: Giulio Macchi

Giulio Macchi (; 1866–1935) was an Italian aeronautical engineer, the founder of ''Società Anonima Nieuport-Macchi'' (now Alenia Aermacchi).

Macchi ran a small coachbuilder's works, ''Carrozzeria Fratelli Macchi'' (Macchi Brothers Coachworks) ...

and Alessandro Tonini of Nieuport-Macchi, Raffaele Conflenti

Raffaele Conflenti (4 December 1889 – 16 July 1946) was an Italian aeronautical engineer and aircraft designer. During his career, he worked for some of the most important seaplane manufacturers in Italy and designed a large number of aircraft in ...

of SIAI. The tests were soon interrupted by the worsening of the weather conditions, but their outcome was positive. The aircraft had proved responsive to the controls, maneuverable and stable; it seemed to be too light towards the bow and at the end of the day some water was found to have leaked inside the fuselage, but Caproni was satisfied.

ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship ...

before carrying out further tests, in order to keep the aircraft from pitching up excessively.

More taxiing tests were successfully carried out on February 11. On February 12 or March 2, 1921, the bow of the aircraft loaded with of ballast, the Transaereo reached the speed of and took off for the first time. During the brief flight it proved stable and maneuverable, in spite of a persisting tendency to climb.

The second flight took place on March 4. Semprini (according to what he later recalled) accelerated the aircraft to 100 or 110 km/h (54–59 kn, 62–68 mph), pulling the yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, u ...

toward himself; suddenly the Transaereo took off and started climbing in a sharp nose-up attitude; the pilot reduced the throttle

A throttle is the mechanism by which fluid flow is managed by constriction or obstruction.

An engine's power can be increased or decreased by the restriction of inlet gases (by the use of a throttle), but usually decreased. The term ''throttle'' ...

, but then the aircraft's tail started falling and the aircraft lost altitude, out of control. The tail soon hit the water and was rapidly followed by the nose of the aircraft, which slammed into the surface, breaking the fore part of the hull. The fore wing set collapsed in the water together with the nose of the aircraft, while the central and the aft wing sets, together with the tail of the aircraft, kept floating. The pilot and the flight engineers escaped the wreck unscathed.

Caproni, coming from Vizzola Ticino by automobile, was delayed, and only arrived on the shore of Lake Maggiore after the Transaereo had crashed. He later commented, "So the fruit of years of work, an aircraft that was to form the basis of future aviation, all is lost in a moment. But one must not be shocked if one wants to progress. The path of progress is strewn with suffering."

At the time, the accident was blamed on two concurrent causes. First, the wake of a steamboat that was navigating on the lake close to the area where the Transaereo was accelerating was thought to have interfered with the takeoff. Second, test pilot Semprini was blamed for having kept pulling the yoke trying to gain altitude while he should have performed corrective maneuvers, for example lowering the nose to let the huge aircraft gain speed. Another theory suggests the aforementioned boat was a ferry loaded with passengers and Semprini (who was only performing some taxiing trials, for he did not mean to take off before Caproni's arrival on the spot) was suddenly compelled to take off, in spite of the insufficient speed, to avoid a collision. According to more recent theories, the cause of the accident was probably the sandbags that had been placed in the aircraft to simulate the weight of passengers: not having been fastened to the seats, they may have slid to the back of the fuselage when, upon takeoff, the Transaereo suddenly pitched up. With the tail burdened by this additional load and a shift in the

Caproni, coming from Vizzola Ticino by automobile, was delayed, and only arrived on the shore of Lake Maggiore after the Transaereo had crashed. He later commented, "So the fruit of years of work, an aircraft that was to form the basis of future aviation, all is lost in a moment. But one must not be shocked if one wants to progress. The path of progress is strewn with suffering."

At the time, the accident was blamed on two concurrent causes. First, the wake of a steamboat that was navigating on the lake close to the area where the Transaereo was accelerating was thought to have interfered with the takeoff. Second, test pilot Semprini was blamed for having kept pulling the yoke trying to gain altitude while he should have performed corrective maneuvers, for example lowering the nose to let the huge aircraft gain speed. Another theory suggests the aforementioned boat was a ferry loaded with passengers and Semprini (who was only performing some taxiing trials, for he did not mean to take off before Caproni's arrival on the spot) was suddenly compelled to take off, in spite of the insufficient speed, to avoid a collision. According to more recent theories, the cause of the accident was probably the sandbags that had been placed in the aircraft to simulate the weight of passengers: not having been fastened to the seats, they may have slid to the back of the fuselage when, upon takeoff, the Transaereo suddenly pitched up. With the tail burdened by this additional load and a shift in the center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

, the aircraft became uncontrollable and the nose lifted more and more, until the Transaereo stalled and violently hit the water tail first.

Ivanoe Bonomi

Ivanoe Bonomi (18 October 1873 – 20 April 1951) was an Italian politician and journalist who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1921 to 1922 and again from 1944 to 1945.

Background and earlier career

Ivanoe Bonomi was born in Mantua, I ...

(who had been the Ministry of War Ministry of War may refer to:

* Ministry of War (imperial China) (c.600–1912)

* Chinese Republic Ministry of War (1912–1946)

* Ministry of War (Kingdom of Bavaria) (1808–1919)

* Ministry of War (Brazil) (1815–1999)

* Ministry of War (Estoni ...

until shortly before), Caproni was convinced he could build a 1/3 scale model and Bonomi promised that, had he won the elections, his cabinet would grant him all the financial support he needed. However, even though Bonomi actually became Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

in July, more urgent political priorities ultimately caused the project of the Transaereo to be abandoned.

Even if, overall, it was not successful, the Caproni Ca.60 keeps being considered "one of the most extraordinary aircraft ever built."

Aircraft on display

Most of the damaged structure of the wreck was lost after the Transaereo project was eventually abandoned. Caproni, however, was convinced of the importance of preserving and honoring the historical heritage related to the birth and early development of Italian aviation in general, and to the Caproni firm in particular; his historical sensibility meant that several parts of the Transaereo, retrospectively known as the Caproni Ca.60, survived: the two outriggers, the lower front section of the main hull, a control and communication panel and one of the Liberty engines were spared and, after following the Caproni Museum in all its whereabouts between its foundation in 1927 and its move to its current location inTrento

Trento ( or ; Ladin and lmo, Trent; german: Trient ; cim, Tria; , ), also anglicized as Trent, is a city on the Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ce ...

in 1992, they were displayed together with the rest of the permanent collection in the main exhibition hall of the museum in 2010.

A section of one of the two triangular truss-booms also survived, as well as one of the hydrofoils that connected the main hull and the outriggers. These fragments are on display at the Volandia

Volandia Park and Flight Museum is the largest Italian aeronautical museum, as well as one of the largest in Europe. Volandia displays over 100 aircraft. The museum covers an area of ca. 60,000 m2 (645,000 sq ft) of which 20,000 m2 (215,000 sq f ...

aviation museum, in the Province of Varese, hosted in the former industrial premises of the Caproni company at Vizzola Ticino

Vizzola Ticino is a village and ''comune'' of the province of Varese in Lombardy, Italy. It is on the banks of the Ticino River, immediately to the west of Strada Provinciale 52 on the western perimeter of Malpensa Airport.

In the late 19th ce ...

.

Specifications (Ca.60)

In popular culture

The Caproni Ca.60 was featured in the 2013 semi-fictional movie ''The Wind Rises

is a 2013 Japanese animated historical drama film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, animated by Studio Ghibli for the Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Hakuhodo DY Media Partners, Walt Disney Japan, Mitsubishi, Toho and KDDI. It was rele ...

'' by Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki

is a Japanese animator, director, producer, screenwriter, author, and manga artist. A co-founder of Studio Ghibli, he has attained international acclaim as a masterful storyteller and creator of Japanese animated feature films, and is widel ...

, as was Caproni himself.

See also

*Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics

The Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics (Italian: ''Museo dell'Aeronautica Gianni Caproni'') is Italy's oldest aviation museum, as well as the country's oldest corporate museum. It was established in 1927 as the Caproni Museum (''Museo Caproni'') ...

* List of experimental aircraft

As used here, an experimental or research and development aircraft, sometimes also called an X-plane, is one which is designed or substantially adapted to investigate novel flight technologies.

Argentina

* FMA I.Ae. 37 glider – testbed for p ...

* List of flying boats and floatplanes

The following is a list of seaplanes, which includes floatplanes and flying boats. A seaplane is any airplane that has the capability of landing and taking off from water, while an amphibian is a seaplane which can also operate from land. (They d ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

* * *Period documentary about the Transaereo

(static display) {{Caproni aircraft 1920s Italian airliners Flying boats Ca.060 Triplanes Tandem-wing aircraft Multiplane aircraft Eight-engined push-pull aircraft Aircraft first flown in 1921