CSS Albemarle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

CSS ''Albemarle'' was a steam-powered

Construction of the ironclad began in January 1863 and continued on during the next year. Word of the gunboat reached the Union naval officers stationed in the region, raising an alarm. They appealed to the

Construction of the ironclad began in January 1863 and continued on during the next year. Word of the gunboat reached the Union naval officers stationed in the region, raising an alarm. They appealed to the

However, two

However, two  On May 5 ''Albemarle'' and , a captured steamer, were escorting the troop-laden down the

On May 5 ''Albemarle'' and , a captured steamer, were escorting the troop-laden down the

''Albemarle'' successfully dominated the Roanoke and the approaches to Plymouth through the summer of 1864. By autumn the U. S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done: The U. S. Navy considered various ways to destroy ''Albemarle'', including two plans submitted by Lieutenant

''Albemarle'' successfully dominated the Roanoke and the approaches to Plymouth through the summer of 1864. By autumn the U. S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done: The U. S. Navy considered various ways to destroy ''Albemarle'', including two plans submitted by Lieutenant  As they approached the Confederate docks their luck turned, and they were spotted in the dark. They came under heavy rifle and pistol fire from both the shore and aboard ''Albemarle''. As they closed with the ironclad, they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating

As they approached the Confederate docks their luck turned, and they were spotted in the dark. They came under heavy rifle and pistol fire from both the shore and aboard ''Albemarle''. As they closed with the ironclad, they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating

After the fall of Plymouth, the U. S. Navy raised and temporarily hull-patched the Confederate ram. Near the end of the war, the Union gunboat towed ''Albemarle'' to the

After the fall of Plymouth, the U. S. Navy raised and temporarily hull-patched the Confederate ram. Near the end of the war, the Union gunboat towed ''Albemarle'' to the

A 3/8 scale replica of ''Albemarle'' has been at anchor near the Port O' Plymouth Museum in

A 3/8 scale replica of ''Albemarle'' has been at anchor near the Port O' Plymouth Museum in

American Civil War Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Albemarle Ironclad warships of the Confederate States Navy Ships built in North Carolina 1860s ships Shipwrecks of the American Civil War Shipwrecks in rivers Ships captured by the United States Navy from the Confederate States Navy Maritime incidents in October 1864 Raids of the American Civil War

casemate ironclad

The casemate ironclad was a type of iron or iron-armored gunboat briefly used in the American Civil War by both the Confederate States Navy and the Union Navy. Unlike a monitor-type ironclad which carried its armament encased in a separate a ...

ram

Ram, ram, or RAM may refer to:

Animals

* A male sheep

* Ram cichlid, a freshwater tropical fish

People

* Ram (given name)

* Ram (surname)

* Ram (director) (Ramsubramaniam), an Indian Tamil film director

* RAM (musician) (born 1974), Dutch

* ...

of the Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American ...

(and later the second ''Albemarle'' of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

), named for an estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

which was named for General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

, the first Duke of Albemarle

The Dukedom of Albemarle () has been created twice in the Peerage of England, each time ending in extinction. Additionally, the title was created a third time by James II in exile and a fourth time by his son the Old Pretender, in the Jacobite ...

and one of the original Carolina Lords Proprietor

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the European ...

.

Construction

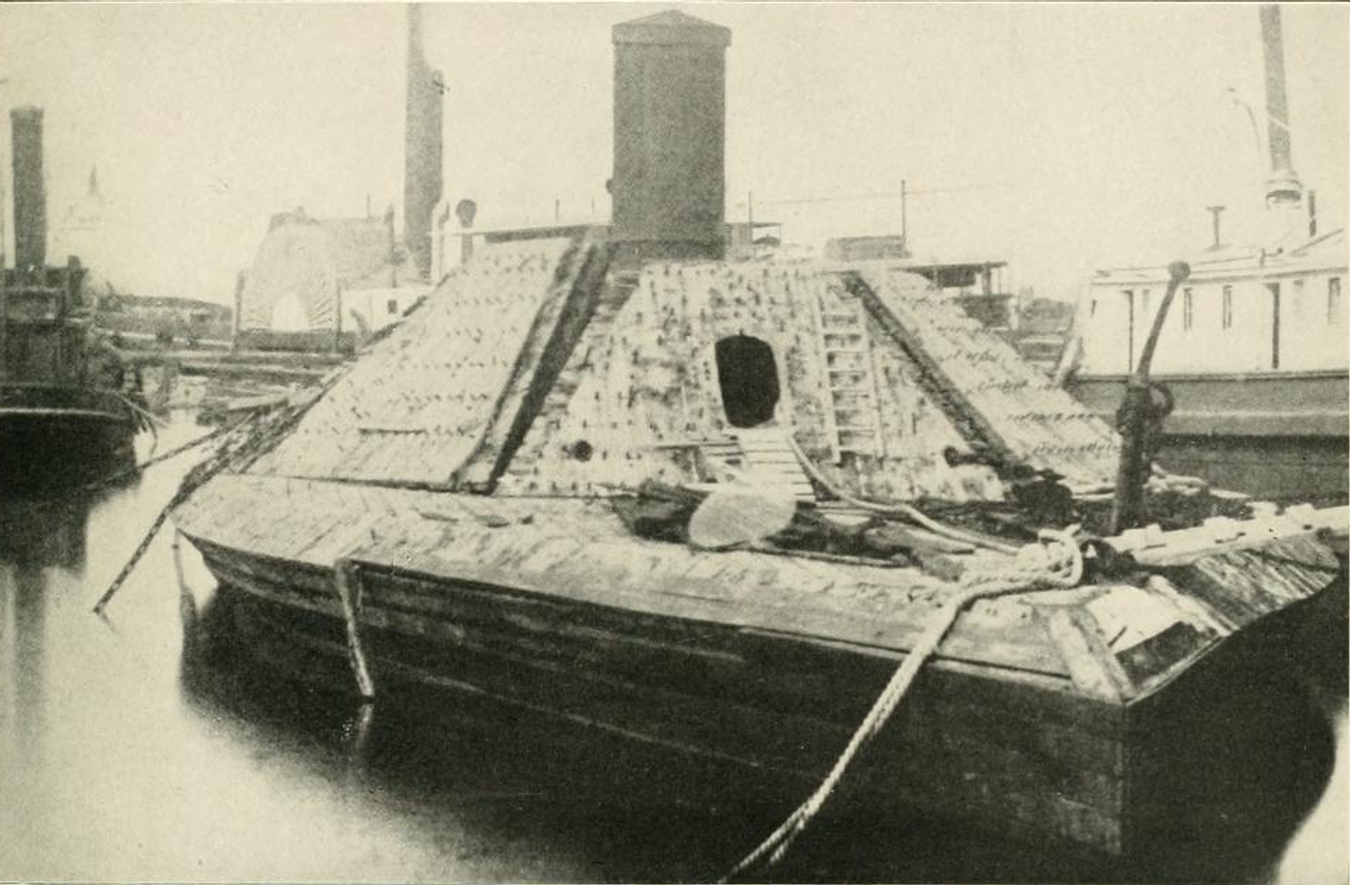

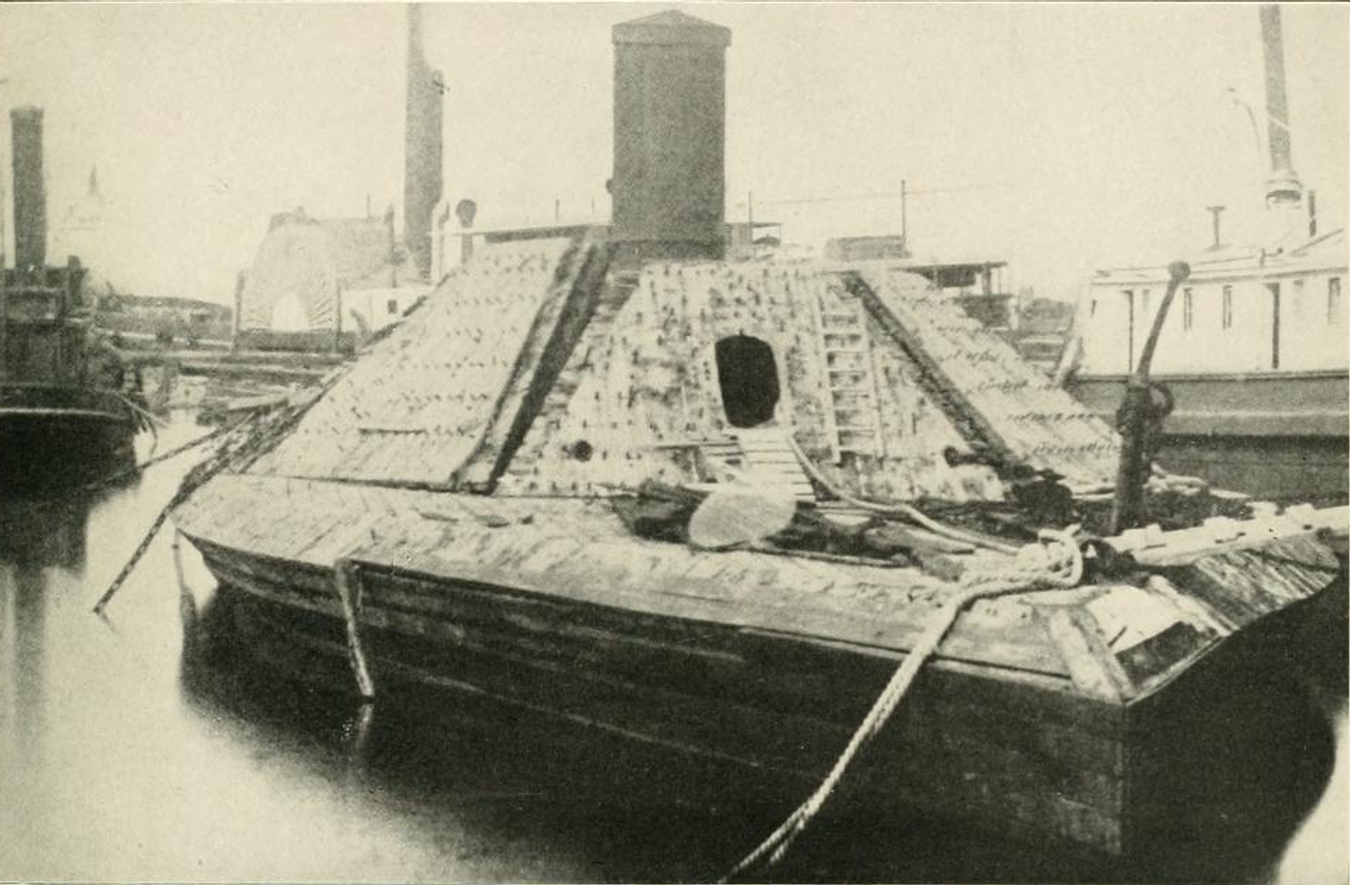

On 16 April 1862, the Confederate Navy Department, enthusiastic about the offensive potential of armored rams following the victory of their first ironclad ram (the rebuilt USS ''Merrimack'') over the wooden-hulledUnion

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

rs in Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, Virginia, signed a contract with nineteen-year-old detached Confederate Lieutenant Gilbert Elliott

Gilbert Elliott (December 10, 1843 – May 9, 1895) was builder of the ironclad ram CSS ''Albemarle''.

Family

Elliott's parents were Gilbert Elliott (May 20, 1813 – May 20, 1851) and Sarah Ann Grice (June 1, 1819 – April 22, 1891 ...

of Elizabeth City, North Carolina

Elizabeth City is a city in Pasquotank County, North Carolina, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 18,629. Elizabeth City is the county seat and largest city of Pasquotank County. It ...

; he was to oversee the construction of a smaller but still powerful gunboat to destroy the Union warships in the North Carolina sounds. These men-of-war had enabled Union troops to hold strategic positions that controlled eastern North Carolina.

Since the terms of the agreement gave Elliott freedom to select an appropriate place to build the ram, he established a primitive shipyard, with the assistance of plantation owner Peter Smith, in a cornfield up the Roanoke River

The Roanoke River ( ) runs long through southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the App ...

at a place called Edward's Ferry, near modern Scotland Neck, North Carolina

Scotland Neck is a town in Halifax County, North Carolina, United States. According to the 2010 census, the town population was 2,059. It is part of the Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The Hoffman-Bower ...

; Smith was appointed the superintendent of construction. There, the water was too shallow to permit the approach of Union gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s that otherwise would have destroyed the ironclad while still on its ways. Using detailed sketches provided by Elliott, the Confederate Navy's Chief Constructor John L. Porter

John Luke Porter (13 September 1813 – 4 December 1893) was a naval constructor for United States Navy and the Confederate States Navy.

Early life

Porter was born in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1813. His mother was Frances Pritchard, daughter of ...

finalized the gunboat's design, giving the ram an armored casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

with eight sloping, 30-degree angle sides. Within this thick-walled bunker were two Brooke pivot rifles, one forward, the other aft, each capable of firing from three different fixed positions. Both cannons were protected on all sides behind six exterior-mounted, heavy iron shutters. The ram was propelled by twin 3-bladed screw propellers powered by two steam engines, each of , and built by Elliott.

Construction of the ironclad began in January 1863 and continued on during the next year. Word of the gunboat reached the Union naval officers stationed in the region, raising an alarm. They appealed to the

Construction of the ironclad began in January 1863 and continued on during the next year. Word of the gunboat reached the Union naval officers stationed in the region, raising an alarm. They appealed to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

for an overland expedition to destroy the ship, to be christened ''Albemarle'' after the body of water into which the Roanoke emptied, but the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

never felt it could spare the troops needed to carry out such a mission; it was a decision that would prove to be very short-sighted.

Ordnance and projectiles

''Albemarle'' was equipped with two Brookerifled cannon

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications dur ...

(similar to a Parrott rifle

The Parrott rifle was a type of muzzle-loading rifled artillery weapon used extensively in the American Civil War.

Parrott rifle

The gun was invented by Captain Robert Parker Parrott, a West Point graduate. He was an American soldier and invent ...

); each double-banded cannon weighed more than with its pivot carriage and other attached hardware. Both cannons were positioned along the ironclad's center-line in the armored casemate, one forward, the other aft. The field of fire

The field of fire of a weapon (or group of weapons) is the area around it that can easily and effectively be reached by gunfire. The term 'field of fire' is mostly used in reference to machine guns. Their fields of fire incorporate the beaten zon ...

for both pivot rifles was 180-degrees, from port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

to starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

: each cannon could fire from one of three gun ports, allowing ''Albemarle'' to deliver a two cannon broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

. ''Albemarle''s projectiles

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

consisted of explosive shells, anti-personnel canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel artillery ammunition. Canister shot has been used since the advent of gunpowder-firing artillery in Western armies. However, canister shot saw particularly frequent use on land and at sea in the various ...

, grape shot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

, and blunt-nosed, solid wrought iron "bolts" for use against Union armored ships. These were an early attempt at armor-piercing shot; solid iron like a typical solid shot

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge, launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a lar ...

, but elongated rather than spherical, giving far more weight for an equal frontal area than a traditional round ball, and thus greater penetration. Such projectiles could not be effectively fired from a traditional smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars.

History

Early firearms had smoothly bored barrels that fired projectiles without signi ...

naval gun, as the lack of stability would cause the shot to tumble in flight.

Service on the Roanoke River

In April 1864 the newly commissioned Confederate States Steamer ''Albemarle'', under the command ofCaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

James W. Cooke

James Wallace Cooke (August 23, 1812 – June 21, 1869) was an American naval officer, serving in the United States Navy and during the American Civil War serving in the Confederate States Navy, Confederate Navy.

Pre-war life

James Wallace Cooke w ...

, got underway down-river toward Plymouth, North Carolina

Plymouth is the largest town in Washington County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 3,878 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County. Plymouth is located on the Roanoke River about seven miles (11 km) upr ...

; its mission was to clear the river of all Union vessels so that General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Robert F. Hoke

Robert Frederick Hoke (May 27, 1837 – July 3, 1912) was a Confederate major general during the American Civil War. He was present at one of the earliest battles, the Battle of Big Bethel, where he was commended for coolness and judgment. Wo ...

's troops could storm the forts located there. She anchored about three miles (5 km) above the town, and the pilot, John Lock, set off with two seamen in a small boat to take soundings. The river was high and they discovered ten feet of water over the obstructions that the Union forces had placed in the Thoroughfare Gap. Captain Cooke immediately ordered steam and, by keeping to the middle of the channel, they passed safely over the obstructions. The ironclad's armor protected them from the Union guns of the forts at Warren's Neck and Boyle's Mill.

However, two

However, two paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

s, and , lashed together with spars and chains, approached from up-river, attempting to pass on either side of ''Albemarle'' in order to trap her between them. Captain Cooke turned heavily to starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

, getting outboard of ''Southfield'', but running dangerously close to the southern shore. Turning back sharply into the river, he rammed the Union sidewheeler, driving her under; ''Albemarle''s ram became trapped in ''Southfield''s hull from the force of the blow, and her bow was pulled under as well. As ''Southfield'' sank, she rolled over before settling on the riverbed; this action released the death grip that held the new Confederate ram.

''Miami'' fired a shell into ''Albemarle'' at point-blank range while she was trapped by the wreck of ''Southfield'', but the shell rebounded off ''Albemarle''s sloping iron armor and exploded on ''Miami'', killing her commanding officer, Captain Charles W. Flusser. ''Miami''s crew attempted to board ''Albemarle'' to capture her but were soon driven back by heavy musket fire; ''Miami'' then steered clear of the ironclad and escaped into Albemarle Sound.

With the river now clear of Union ships, and with the assistance of ''Albemarle''s rifled cannon, General Hoke attacked and took Plymouth and the nearby forts.

On May 5 ''Albemarle'' and , a captured steamer, were escorting the troop-laden down the

On May 5 ''Albemarle'' and , a captured steamer, were escorting the troop-laden down the Roanoke River

The Roanoke River ( ) runs long through southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the App ...

; they encountered a flotilla of eight Union warships, including USS ''Miami'', , , and , in what would become known as the Battle of Albemarle Sound

The Battle of Albemarle Sound was an inconclusive naval battle fought in May 1864 along the coast of North Carolina during the American Civil War. Three Confederate warships, including an ironclad, engaged eight Union gunboats. The action end ...

. All four of the listed ships combined mounted more than sixty cannons. ''Albemarle'' opened fire first, wounding six men working one of ''Mattabesett''s two 100-pounder Parrott rifle

The Parrott rifle was a type of muzzle-loading rifled artillery weapon used extensively in the American Civil War.

Parrott rifle

The gun was invented by Captain Robert Parker Parrott, a West Point graduate. He was an American soldier and invent ...

s, and then attempted to ram her, but the sidewheeler

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

managed to round the ironclad's armored bow. She was closely followed by ''Sassacus'', which then fired a broadside of solid and 100-pound shot, all of which bounced off ''Albemarle''s casemate armor. However, ''Bombshell'', being a softer target, was hulled by each heavy shot from ''Sassucus''s broadside and was quickly captured by Union forces, following her surrender.

Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Francis Asbury Roe

Francis Asbury Roe (October 4, 1823 – December 28, 1901) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served during the American Civil War.

Biography

Born in Elmira, New York, Roe entered the United States Navy as a midshipman on October 1 ...

of ''Sassucus'', seeing ''Albemarle'' at a range of about , decided to ram. The Union ship struck the Confederate ironclad full and square, broadside-on, shattering the timbers of her own bow, twisting off her own bronze ram in the process, and jamming both ships together. With ''Sassucus''s hull almost touching the end of the ram's Brooke rifle, ''Albemarle''s gun crew quickly fired two point-blank rifled shells, one of them puncturing ''Sassucus''s boilers; though live steam was roaring through the ship, she was able to break away and drift out of range. ''Miami'' first tried to use her spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

and then to tangle the Confederate rams screw propellers and rudder with a seine net

Seine fishing (or seine-haul fishing; ) is a method of fishing that employs a surrounding net, called a seine, that hangs vertically in the water with its bottom edge held down by weights and its top edge buoyed by floats. Seine nets can be dep ...

, but neither ploy succeeded. More than 500 shells were fired at ''Albemarle'' during the battle; with visible battle damage to her smokestack

A chimney is an architectural ventilation structure made of masonry, clay or metal that isolates hot toxic exhaust gases or smoke produced by a boiler, stove, furnace, incinerator, or fireplace from human living areas. Chimneys are typic ...

and other areas on the ironclad, she steamed back up the Roanoke, soon mooring at Plymouth.

Sinking

''Albemarle'' successfully dominated the Roanoke and the approaches to Plymouth through the summer of 1864. By autumn the U. S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done: The U. S. Navy considered various ways to destroy ''Albemarle'', including two plans submitted by Lieutenant

''Albemarle'' successfully dominated the Roanoke and the approaches to Plymouth through the summer of 1864. By autumn the U. S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done: The U. S. Navy considered various ways to destroy ''Albemarle'', including two plans submitted by Lieutenant William B. Cushing

William Barker Cushing (4 November 184217 December 1874) was an officer in the United States Navy, best known for sinking the during a daring nighttime raid on 27 October 1864, for which he received the Thanks of Congress. Cushing was the youn ...

; they finally approved one of his plans, authorizing him to locate two small steam launches that might be fitted with spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

es. Cushing discovered two picket boats under construction in New York and acquired them for his mission ome accounts have them as 45 to 47 feet (14 m) On each he mounted a Dahlgren 12-pounder howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

and a spar projecting into the water from its bow. One of the boats was lost at sea during the voyage from New York to Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, but the other arrived safely with its crew of seven officers and men at the mouth of the Roanoke. There, the steam launch's spar was fitted with a lanyard-detonated torpedo.

On the night of October 27 and 28, 1864, Cushing and his team began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a schooner anchored to the wreck of ''Southfield''; both boats, under the cover of darkness, slipped past the schooner undetected. So Cushing decided to use all twenty-two of his men and the element of surprise to capture ''Albemarle''.

As they approached the Confederate docks their luck turned, and they were spotted in the dark. They came under heavy rifle and pistol fire from both the shore and aboard ''Albemarle''. As they closed with the ironclad, they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating

As they approached the Confederate docks their luck turned, and they were spotted in the dark. They came under heavy rifle and pistol fire from both the shore and aboard ''Albemarle''. As they closed with the ironclad, they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating log boom

A log boom (sometimes called a log fence or log bag) is a barrier placed in a river, designed to collect and or contain floating logs timbered from nearby forests. The term is also used as a place where logs were collected into booms, as at the ...

s. The logs, however, had been in the water for many months and were covered with heavy slime. The steam launch rode up and then over them without difficulty; with her spar fully against the ironclad's hull, Cushing stood up in the bow and pulled the lanyard, detonating the torpedo's explosive charge.

The explosion threw Cushing and his men overboard into the water; Cushing then stripped off most of his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid undercover until daylight, avoiding the hastily organized Confederate search parties. The next afternoon, he was finally able to steal a small skiff

A skiff is any of a variety of essentially unrelated styles of small boats. Traditionally, these are coastal craft or river craft used for leisure, as a utility craft, and for fishing, and have a one-person or small crew. Sailing skiffs have devel ...

and began slowly paddling, using his hands and arms as oars, down-river to rejoin Union forces at the river's mouth. Cushing's long journey was quite perilous and he was nearly captured and almost drowned before finally reaching safety, totally exhausted by his ordeal; he was hailed a national hero of the Union cause for his daring exploits. Of the other men in Cushing's launch, one man, Seaman Edward Houghton, also escaped, two others .M.M. John Woodman and 1/C fireman Samuel Higginswere drowned following the explosion, and the remaining eleven were captured.

Cushing's daring commando

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

raid blew a hole in ''Albemarle''s hull at the waterline "big enough to drive a wagon in." She sank immediately in the six feet of water below her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

, settling into the heavy river bottom mud, leaving the upper casemate mostly dry and the ship's large Stainless Banner ensign flying from the flagstaff at the rear of the casemate's upper deck. Confederate commander Alexander F. Warley, who had been appointed as her captain about a month earlier, later salvaged both of ''Albemarle''s rifled cannon and shells and used them to defend Plymouth against subsequent Union attack.

Lieutenant Cushing's successful effort to neutralize CSS ''Albemarle'' is honored by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

with a battle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

on the Civil War campaign streamer

Campaign streamers are decorations attached to military flags to recognize particular achievements or events of a military unit or service. Attached to the headpiece of the assigned flag, the streamer often is an inscribed ribbon with the n ...

.

Raising and later service

After the fall of Plymouth, the U. S. Navy raised and temporarily hull-patched the Confederate ram. Near the end of the war, the Union gunboat towed ''Albemarle'' to the

After the fall of Plymouth, the U. S. Navy raised and temporarily hull-patched the Confederate ram. Near the end of the war, the Union gunboat towed ''Albemarle'' to the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

, where she arrived on 27 April 1865. On 7 June orders were issued to repair her hull, and she entered dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

soon thereafter. The work was completed on 14 August 1865. Two weeks later, the ironclad was judged condemned by a Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

prize court

A prize court is a court (or even a single individual, such as an ambassador or consul) authorized to consider whether prizes have been lawfully captured, typically whether a ship has been lawfully captured or seized in time of war or under the te ...

.

She saw no active naval service after being placed in ordinary at Norfolk, where she remained until she was finally sold at public auction

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

on 15 October 1867 to J. N. Leonard and Company. She was probably scrapped

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

for salvage. One of her double-banded Brooke rifled cannon is on display at the Headquarters of the Commander U. S. Fleet Forces Command at the Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, naval base. Her smokestack is on display at the Museum of the Albemarle

The Museum of the Albemarle is located in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It serves as the northeastern regional branch of the North Carolina Museum of History. This area of North Carolina is sometimes considered the birthplace of English North ...

in Elizabeth City, North Carolina

Elizabeth City is a city in Pasquotank County, North Carolina, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 18,629. Elizabeth City is the county seat and largest city of Pasquotank County. It ...

. Her bell is on display at the Port o' Plymouth Museum in Plymouth, North Carolina.

Prize Court Adjudication

Replica

A 3/8 scale replica of ''Albemarle'' has been at anchor near the Port O' Plymouth Museum in

A 3/8 scale replica of ''Albemarle'' has been at anchor near the Port O' Plymouth Museum in Plymouth, North Carolina

Plymouth is the largest town in Washington County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 3,878 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County. Plymouth is located on the Roanoke River about seven miles (11 km) upr ...

since April 2002. The replica is self-powered and capable of sailing on the river. Each year, the replica takes to the water during Living History Weekend in the last weekend of April.

See also

* Ships captured in the American Civil War * Bibliography of American Civil War naval historyNotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

American Civil War Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Albemarle Ironclad warships of the Confederate States Navy Ships built in North Carolina 1860s ships Shipwrecks of the American Civil War Shipwrecks in rivers Ships captured by the United States Navy from the Confederate States Navy Maritime incidents in October 1864 Raids of the American Civil War