Burke and Hare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in

Knox was an anatomist who had qualified as a doctor in 1814. After contracting

Knox was an anatomist who had qualified as a doctor in 1814. After contracting

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney,

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney,  William Hare was probably born in

William Hare was probably born in

Burke met two women in early April: Mary Paterson (also known as Mary Mitchell) and Janet Brown, in the Canongate area of Edinburgh. He bought the two women alcohol before inviting them back to his lodging for breakfast. The three left the tavern with two bottles of whisky and went instead to his brother Constantine's house. After his brother left for work, Burke and the women finished the whisky and Paterson fell asleep at the table; Burke and Brown continued talking but were interrupted by McDougal, who accused them of having an affair. A row broke out between Burke and McDougal—during which he threw a glass at her, cutting her over the eye—Brown stated that she did not know Burke was married and left; McDougal also left, and went to fetch Hare and his wife. They arrived shortly afterwards and the two men locked their wives out of the room, then murdered Paterson in her sleep. That afternoon the pair took the body to Knox in a tea-chest, while McDougal kept Paterson's skirt and petticoats; they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it. Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate". Knox was delighted with the corpse, and stored it in whisky for three months before dissecting it. When Brown later searched for her friend, she was told that she had left for

Burke met two women in early April: Mary Paterson (also known as Mary Mitchell) and Janet Brown, in the Canongate area of Edinburgh. He bought the two women alcohol before inviting them back to his lodging for breakfast. The three left the tavern with two bottles of whisky and went instead to his brother Constantine's house. After his brother left for work, Burke and the women finished the whisky and Paterson fell asleep at the table; Burke and Brown continued talking but were interrupted by McDougal, who accused them of having an affair. A row broke out between Burke and McDougal—during which he threw a glass at her, cutting her over the eye—Brown stated that she did not know Burke was married and left; McDougal also left, and went to fetch Hare and his wife. They arrived shortly afterwards and the two men locked their wives out of the room, then murdered Paterson in her sleep. That afternoon the pair took the body to Knox in a tea-chest, while McDougal kept Paterson's skirt and petticoats; they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it. Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate". Knox was delighted with the corpse, and stored it in whisky for three months before dissecting it. When Brown later searched for her friend, she was told that she had left for  The final victim, killed on 31 October 1828, was Margaret Docherty, a middle-aged Irish woman. Burke lured her into the Broggan lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of McDougal while he went out, ostensibly to buy more whisky, but actually to get Hare. Two other lodgers—Ann and James Gray—were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare's lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret had joined in. At around 9:00 pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Although Burke and Hare came to blows at some point in the evening, they subsequently murdered Docherty, and put her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty's body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into McDougal who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week; they refused. While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox's surgery. The police search located Docherty's bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed. When questioned, Burke and his wife claimed that Docherty had left the house, but gave different times for her departure. This raised enough suspicion for the police to take them in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox's dissecting-rooms where they found Docherty's body; James identified her as the woman he had seen with Burke and Hare. Hare and his wife were arrested that day, as was Broggan; all denied any knowledge of the events.

In total sixteen people were murdered by Burke and Hare. Burke stated later that he and Hare were "generally in a state of intoxication" when the murders were carried out, and that he "could not sleep at night without a bottle of whisky by his bedside, and a twopenny candle to burn all night beside him; when he awoke he would take a drink from the bottle—sometimes half a bottle at a draught—and that would make him sleep." He also took

The final victim, killed on 31 October 1828, was Margaret Docherty, a middle-aged Irish woman. Burke lured her into the Broggan lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of McDougal while he went out, ostensibly to buy more whisky, but actually to get Hare. Two other lodgers—Ann and James Gray—were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare's lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret had joined in. At around 9:00 pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Although Burke and Hare came to blows at some point in the evening, they subsequently murdered Docherty, and put her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty's body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into McDougal who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week; they refused. While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox's surgery. The police search located Docherty's bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed. When questioned, Burke and his wife claimed that Docherty had left the house, but gave different times for her departure. This raised enough suspicion for the police to take them in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox's dissecting-rooms where they found Docherty's body; James identified her as the woman he had seen with Burke and Hare. Hare and his wife were arrested that day, as was Broggan; all denied any knowledge of the events.

In total sixteen people were murdered by Burke and Hare. Burke stated later that he and Hare were "generally in a state of intoxication" when the murders were carried out, and that he "could not sleep at night without a bottle of whisky by his bedside, and a twopenny candle to burn all night beside him; when he awoke he would take a drink from the bottle—sometimes half a bottle at a draught—and that would make him sleep." He also took

On 3 November 1828 a warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives; Broggan was released without further action. The four suspects were kept apart and statements taken; these conflicted with the initial answers given on the day of their arrests. After Alexander Black, a police surgeon, examined Docherty's body, two forensic specialists were appointed, Robert Christison and William Newbigging; they reported that it was probable the victim had been murdered by suffocation, but this could not be medically proven. On the basis of the report from the two doctors, the Burkes and Hares were charged with murder. As part of his investigation Christison interviewed Knox, who asserted that Burke and Hare had watched poor lodging houses in Edinburgh and purchased bodies before anyone claimed them for burial. Christison thought Knox was "deficient in principle and heart", but did not think he had broken the law.

Although the police were sure murder had taken place, and that at least one of the four was guilty, they were uncertain whether they could secure a conviction. Police also suspected there had been other murders committed, but the lack of bodies hampered this line of enquiry. As news of the possibility of other murders came to the public's attention, newspapers began to publish lurid and inaccurate stories of the crimes; speculative reports led members of the public to assume that all missing people had been victims. Janet Brown went to the police and identified her friend Mary Paterson's clothing, while a local baker informed them that Jamie Wilson's trousers were being worn by Burke's nephew. On 19 November a warrant for the murder of Jamie Wilson was made against the four suspects.

Sir William Rae, the

On 3 November 1828 a warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives; Broggan was released without further action. The four suspects were kept apart and statements taken; these conflicted with the initial answers given on the day of their arrests. After Alexander Black, a police surgeon, examined Docherty's body, two forensic specialists were appointed, Robert Christison and William Newbigging; they reported that it was probable the victim had been murdered by suffocation, but this could not be medically proven. On the basis of the report from the two doctors, the Burkes and Hares were charged with murder. As part of his investigation Christison interviewed Knox, who asserted that Burke and Hare had watched poor lodging houses in Edinburgh and purchased bodies before anyone claimed them for burial. Christison thought Knox was "deficient in principle and heart", but did not think he had broken the law.

Although the police were sure murder had taken place, and that at least one of the four was guilty, they were uncertain whether they could secure a conviction. Police also suspected there had been other murders committed, but the lack of bodies hampered this line of enquiry. As news of the possibility of other murders came to the public's attention, newspapers began to publish lurid and inaccurate stories of the crimes; speculative reports led members of the public to assume that all missing people had been victims. Janet Brown went to the police and identified her friend Mary Paterson's clothing, while a local baker informed them that Jamie Wilson's trousers were being worn by Burke's nephew. On 19 November a warrant for the murder of Jamie Wilson was made against the four suspects.

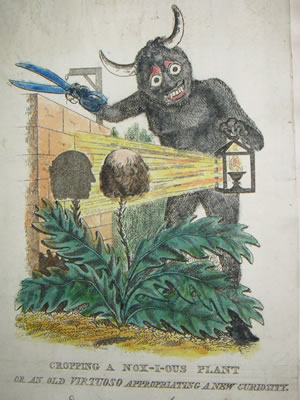

Sir William Rae, the  Knox faced no charges for the murders because Burke's statement to the police exonerated the surgeon. Public awareness of the news grew as newspapers and broadsides began releasing further details. Opinion was against Knox and, according to Bailey, many in Edinburgh thought he was "a sinister ringmaster who got Burke and Hare dancing to his tune". Several broadsides were published with editorials stating that he should have been in the dock alongside the murderers, which influenced public opinion. A new word was coined from the murders: '' burking'', to smother a victim or to commit an

Knox faced no charges for the murders because Burke's statement to the police exonerated the surgeon. Public awareness of the news grew as newspapers and broadsides began releasing further details. Opinion was against Knox and, according to Bailey, many in Edinburgh thought he was "a sinister ringmaster who got Burke and Hare dancing to his tune". Several broadsides were published with editorials stating that he should have been in the dock alongside the murderers, which influenced public opinion. A new word was coined from the murders: '' burking'', to smother a victim or to commit an

McDougal was released at the end of the trial and returned home. The following day she went to buy whisky and was confronted by a mob who were angry at the not proven verdict. She was taken to a police building in nearby Fountainbridge for her own protection, but after the mob laid siege to it she escaped through a back window to the main police station off Edinburgh's High Street. She tried to see Burke, but permission was refused; she left Edinburgh the next day, and there are no clear accounts of her later life. On 3 January 1829, on the advice of both Catholic priests and Presbyterian clergy, Burke made another confession. This was more detailed than the official one provided prior to his trial; he placed much of the blame for the murders on Hare.

On 16 January 1829 a

McDougal was released at the end of the trial and returned home. The following day she went to buy whisky and was confronted by a mob who were angry at the not proven verdict. She was taken to a police building in nearby Fountainbridge for her own protection, but after the mob laid siege to it she escaped through a back window to the main police station off Edinburgh's High Street. She tried to see Burke, but permission was refused; she left Edinburgh the next day, and there are no clear accounts of her later life. On 3 January 1829, on the advice of both Catholic priests and Presbyterian clergy, Burke made another confession. This was more detailed than the official one provided prior to his trial; he placed much of the blame for the murders on Hare.

On 16 January 1829 a  Burke was

Burke was  Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare. The common thought in Edinburgh was that he was culpable in the events; he was lampooned in caricature and, in February 1829, a crowd gathered outside his house and burned an effigy of him. A committee of inquiry cleared him of complicity and reported that they had "seen no evidence that Dr Knox or his assistants knew that murder was committed in procuring any of the subjects brought to his rooms". He resigned from his position as curator of the College of Surgeons' museum, and was gradually excluded from university life by his peers. He left Edinburgh in 1842 and lectured in Britain and mainland Europe. While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the

Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare. The common thought in Edinburgh was that he was culpable in the events; he was lampooned in caricature and, in February 1829, a crowd gathered outside his house and burned an effigy of him. A committee of inquiry cleared him of complicity and reported that they had "seen no evidence that Dr Knox or his assistants knew that murder was committed in procuring any of the subjects brought to his rooms". He resigned from his position as curator of the College of Surgeons' museum, and was gradually excluded from university life by his peers. He left Edinburgh in 1842 and lectured in Britain and mainland Europe. While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the

The question of the supply of cadavers for scientific research had been promoted by the English

The question of the supply of cadavers for scientific research had been promoted by the English

Historical case notes review at the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh

Street literature related to Burke and Hare

at the

Echoes of the Scottish Resurrection Men

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burke And Hare Murders 19th-century executions by Scotland 19th century in Edinburgh 1792 births 1827 murders in the United Kingdom 1828 murders in the United Kingdom 1827 in Scotland 1828 in Scotland 1829 deaths 1859 deaths Criminal duos Executed British serial killers History of anatomy History of Edinburgh Male serial killers Medical serial killers Murder in Edinburgh Murder in Scotland Old Town, Edinburgh People from County Tyrone Scottish serial killers Serial murders in the United Kingdom

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teach ...

for dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

at his anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

lectures.

Edinburgh was a leading European centre of anatomical study in the early 19th century, in a time when the demand for cadaver

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

s led to a shortfall in legal supply. Scottish law required that corpses used for medical research should only come from those who had died in prison, suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

victims, or from foundlings and orphans. The shortage of corpses led to an increase in body snatching

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from ...

by what were known as "resurrection men". Measures to ensure graves were left undisturbed—such as the use of mortsafes—exacerbated the shortage. When a lodger in Hare's house died, he turned to his friend Burke for advice and they decided to sell the body to Knox. They received what was, for them, the generous sum of £7 10s. A little over two months later, when Hare was concerned that a lodger with a fever would deter others from staying in the house, he and Burke murdered her and sold the body to Knox. The men continued their murder spree, probably with the knowledge of their wives. Burke and Hare's actions were uncovered after other lodgers discovered their last victim, Margaret Docherty, and contacted the police.

A forensic examination of Docherty's body indicated she had probably been suffocated, but this could not be proven. Although the police suspected Burke and Hare of other murders, there was no evidence on which they could take action. An offer was put to Hare granting immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity de ...

from prosecution if he turned king's evidence. He provided the details of Docherty's murder and confessed to all sixteen deaths; formal charges were made against Burke and his wife for three murders. At the subsequent trial Burke was found guilty of one murder and sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. The case against his wife was found not proven—a Scottish legal verdict

In law, a verdict is the formal finding of fact made by a jury on matters or questions submitted to the jury by a judge. In a bench trial, the judge's decision near the end of the trial is simply referred to as a finding. In England and Wales ...

to acquit an individual but not declare them innocent. Burke was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The '' Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

shortly afterwards; his corpse was dissected and his skeleton displayed at the Anatomical Museum of Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine. It was es ...

where, , it remains.

The murders raised public awareness of the need for bodies for medical research and contributed to the passing of the Anatomy Act 1832. The events have made appearances in literature, and been portrayed on screen, either in heavily fictionalised accounts or as the inspiration for fictional works.

Background

Anatomy in 19th-century Edinburgh

In the early 19th centuryEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

had several pioneering anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

teachers, including Alexander Monro, his son who was also called Alexander, John Bell, John Goodsir and Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teach ...

, all of whom developed the subject into a modern science. Because of their efforts, Edinburgh became one of the leading European centres of anatomical study, alongside Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration w ...

in the Netherlands and the Italian city of Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

. The teaching of anatomy—crucial in the study of surgery—required a sufficient supply of cadaver

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

s, the demand for which increased as the science developed. Scottish law determined that suitable corpses on which to undertake the dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

s were those who died in prison, suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

victims, and the bodies of foundlings and orphans. With the rise in prestige and popularity of medical training in Edinburgh, the legal supply of corpses failed to keep pace with the demand; students, lecturers and grave robbers—also known as resurrection men

''Resurrection Men'' is a 2002 novel by Ian Rankin. It is the thirteenth of the Inspector Rebus novels. It won the Edgar Award for Best Novel in 2004.

Plot summary

Detective Inspector John Rebus has been sent to Tulliallan, the Scottish Pol ...

—began an illicit trade in exhumed cadavers.

The situation was confused by the legal position. Disturbing a grave was a criminal offence, as was the taking of property from the deceased. Stealing the body itself was not an offence, as it did not legally belong to anyone. The price per corpse changed depending on the season. It was £8 during the summer, when the warmer temperatures brought on quicker decomposition

Decomposition or rot is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and ...

, and £10 in the winter months, when the demand by anatomists was greater, because the lower temperatures meant they could store corpses longer so they undertook more dissections.

By the 1820s the residents of Edinburgh had taken to the streets to protest at the increase in grave robbing. To avoid corpses being disinterred, bereaved families used several techniques in order to deter the thieves: guards were hired to watch the graves, and watchtowers were built in several cemeteries; some families hired a large stone slab that could be placed over a grave for a short period—until the body had begun to decay past the point of being useful for an anatomist. Other families used a mortsafe, an iron cage that surrounded the coffin. The high levels of vigilance from the public, and the techniques used to deter the grave robbers, led to what the historian Ruth Richardson describes as "a growing atmosphere of crisis" among anatomists because of the shortage of corpses. The historian Tim Marshall considers the situation meant "Burke and Hare took graverobbing to its logical conclusion: instead of digging up the dead, they accepted lucrative incentives to destroy the living".

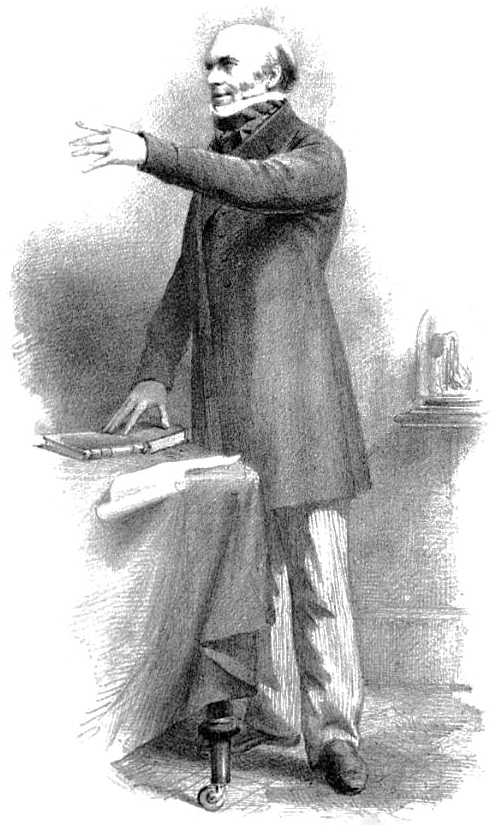

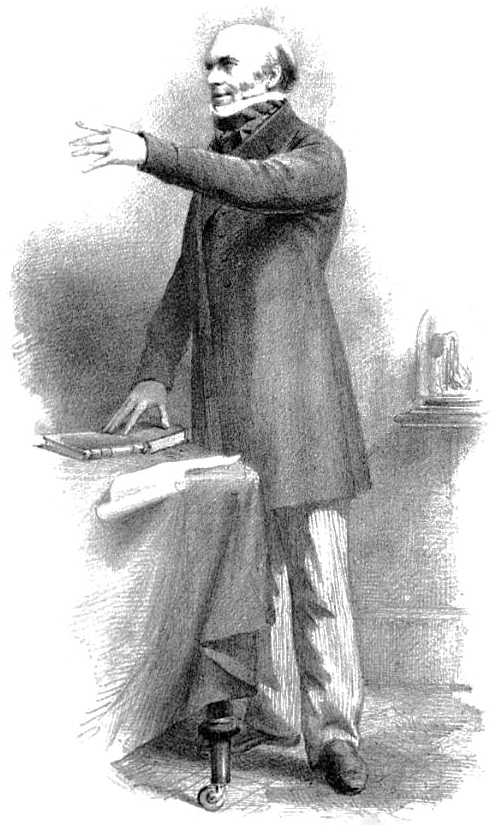

Robert Knox

Knox was an anatomist who had qualified as a doctor in 1814. After contracting

Knox was an anatomist who had qualified as a doctor in 1814. After contracting smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

as a child, he was blind in one eye and badly disfigured. He undertook service as an army physician at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

in 1815, followed by a posting in England and then, during the Cape Frontier War (1819), in southern Africa. He eventually settled in his home town of Edinburgh in 1820. In 1825 he became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

, where he lectured on anatomy. He undertook dissections twice a day, and his advertising promised "a full demonstration on fresh anatomical subjects" as part of every course of lectures he delivered; he stated that his lessons drew over 400 pupils. Clare Taylor, his biographer in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', observes that he "built up a formidable reputation as a teacher and lecturer and almost single-handedly raised the profile of the study of anatomy in Britain". Another biographer, Isobel Rae, considers that without Knox, the study of anatomy in Britain "might not have progressed as it did".

William Burke and William Hare

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney,

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney, County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an administrative division for local government but retai ...

, Ireland, one of two sons to middle-class parents. Burke, along with his brother, Constantine, had a comfortable upbringing, and both joined the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

as teenagers. Burke served in the Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

militia until he met and married a woman from County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

, where they later settled. The marriage was short-lived; in 1818, after an argument with his father-in-law over land ownership, Burke deserted his wife and family. He moved to Scotland and became a labourer, working on the Union Canal

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** '' ...

. He settled in the small village of Maddiston

Maddiston is a village in the Falkirk council area of Scotland. It lies west-southwest of Linlithgow, south of Polmont and south-east of Rumford at the south-east edge of the Falkirk urban area.

Population

Based on the United Kingdom 2001 ce ...

near Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had ...

, and set up home with Helen McDougal, whom he affectionately nicknamed Nelly; she became his second wife. After a few years, and when the works on the canal were finished, the couple moved to Tanners Close, Edinburgh, in November 1827. They became hawkers, selling second-hand clothes to impoverished locals. Burke then became a cobbler, a trade in which he experienced some success, earning upwards of £1 a week. He became known locally as an industrious and good-humoured man who often entertained his clients by singing and dancing for them on their doorsteps while plying his trade. Although raised as a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, Burke became a regular worshipper at Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

religious meetings held in the Grassmarket

The Grassmarket is a historic market place, street and event space in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In relation to the rest of the city it lies in a hollow, well below surrounding ground levels.

Location

The Grassmarket is located direct ...

; he was seldom seen without a bible.

William Hare was probably born in

William Hare was probably born in County Armagh

County Armagh (, named after its county town, Armagh) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the southern shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of an ...

, County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. ...

or in Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Armagh, Armagh and County Down, Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry ...

. His age and year of birth are unknown; when arrested in 1828 he gave his age as 21, but one source states that he was born between 1792 and 1804. Information on his earlier life is scant, although it is possible that he worked in Ireland as an agricultural labourer before travelling to Britain. He worked on the Union Canal for seven years before moving to Edinburgh in the mid-1820s, where he worked as a coal man's assistant. He lodged at Tanner's Close, in the house of a man named Logue and his wife, Margaret Laird, in the nearby West Port area of the town. When Logue died in 1826, Hare may have married Margaret. Based on contemporary accounts, Brian Bailey in his history of the murders describes Hare as "illiterate and uncouth—a lean, quarrelsome, violent and amoral character with the scars from old wounds about his head and brow". Bailey describes Margaret, who was also an Irish immigrant, as a "hard-featured and debauched virago

A virago is a woman who demonstrates abundant masculine virtues. The word comes from the Latin word ''virāgō'' ( genitive virāginis) meaning vigorous' from ''vir'' meaning "man" or "man-like" (cf. virile and virtue) to which the suffix ''-ā ...

".

In 1827 Burke and McDougal went to Penicuik in Midlothian

Midlothian (; gd, Meadhan Lodainn) is a historic county, registration county, lieutenancy area and one of 32 council areas of Scotland used for local government. Midlothian lies in the east- central Lowlands, bordering the City of Edinbu ...

to work on the harvest, where they met Hare. The men became friends; when Burke and McDougal returned to Edinburgh, they moved into Hare's Tanner's Close lodging house, where the two couples soon acquired a reputation for hard drinking and boisterous behaviour.

Events of November 1827 to November 1828

On 29 November 1827 Donald, a lodger in Hare's house, died ofdropsy

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

shortly before receiving a quarterly army pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

while owing £4 of back rent. After Hare bemoaned his financial loss to Burke, the pair decided to sell Donald's body to one of the local anatomists. A carpenter provided a coffin for a burial which was to be paid for by the local parish. After he left, the pair opened the coffin, removed the body—which they hid under the bed—filled the coffin with bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, e ...

from a local tanners and resealed it. After dark, on the day the coffin was removed for burial, they took the corpse to Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

, where they looked for a purchaser. According to Burke's later testimony, they asked for directions to Professor Monro, but a student sent them to Knox's premises in Surgeon's Square. Although the men dealt with juniors when discussing the possibility of selling the body, it was Knox who arrived to fix the price at £7 10 s. Hare received £4 5s while Burke took the balance of £3 5s; Hare's larger share was to cover his loss from Donald's unpaid rent. According to Burke's official confession, as he and Hare left the university, one of Knox's assistants told them that the anatomists "would be glad to see them again when they had another to dispose of".

There is no agreement as to the order in which the murders took place. Burke made two confessions but gave different sequences for the murders in each statement. The first was an official one, given on 3 January 1829 to the sheriff-substitute

In the Courts of Scotland, a sheriff-substitute was the historical name for the judges who sit in the local sheriff courts under the direction of the sheriffs principal; from 1971 the sheriffs substitute were renamed simply as sheriff. When rese ...

, the procurator fiscal and the assistant sheriff-clerk. The second was in the form of an interview with the '' Edinburgh Courant'' that was published on 7 February 1829. These in turn differed from the order given in Hare's statement, although the pair were agreed on many of the points of the murders. Contemporary reports also differ from the confessions of the two men. More recent sources, including the accounts written by Brian Bailey, Lisa Rosner and Owen Dudley Edwards, either follow one of the historic versions or present their own order of events.

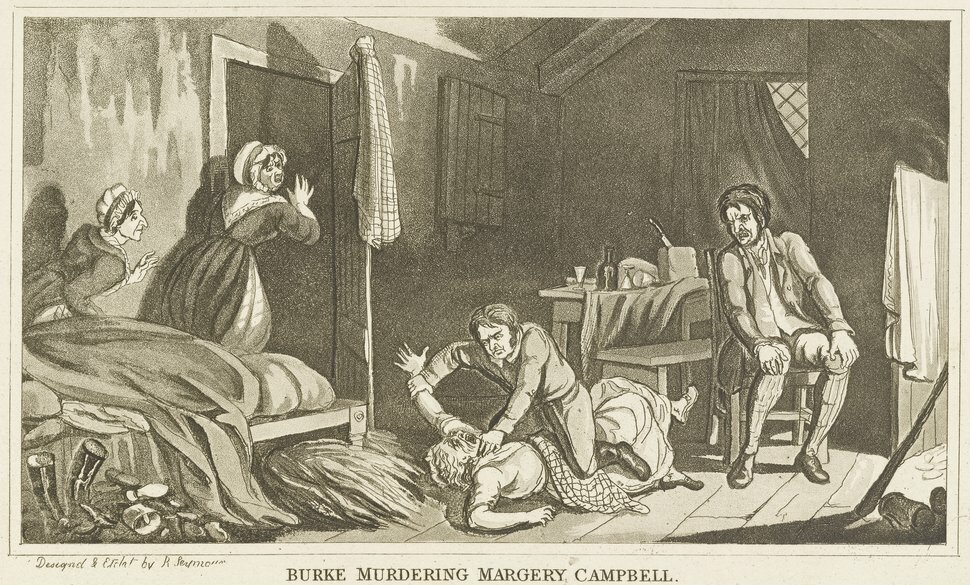

Most of the sources agree that the first murder in January or February 1828 was either that of a miller

A miller is a person who operates a mill, a machine to grind a grain (for example corn or wheat) to make flour. Milling is among the oldest of human occupations. "Miller", "Milne" and other variants are common surnames, as are their equivalent ...

named Joseph lodging in Hare's house, or a salt seller named Abigail Simpson. The historian Lisa Rosner considers Joseph the more likely; a pillow was used to smother the victim, while later ones were suffocated by a hand over the nose and mouth. The novelist Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

, who took a keen interest in the case, also thought the miller was the more likely first victim, and highlighted that "there was an additional motive to reconcile them to the deed", as Joseph had developed a fever and had become delirious. Hare and his wife were concerned that having a potentially infectious lodger would be bad for business. Hare again turned to Burke and, after providing their victim with whisky

Whisky or whiskey is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden ca ...

, Hare suffocated Joseph while Burke lay across the upper torso to restrict movement. They again took the corpse to Knox, who this time paid £10. Rosner considers the method of murder to be ingenious: Burke's weight on the victim stifled movement—and thus the ability to make noise—while it also prevented the chest from expanding should any air get past Hare's suffocating grip. In Rosner's opinion, the method would have been "practically undetectable until the era of modern forensics".

The order of the two victims next after Joseph is also unclear; Rosner puts the sequence as Abigail Simpson followed by an English male lodger from Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, while Bailey and Dudley Edwards each have the order as the English male lodger followed by Simpson. The unnamed Englishman was a travelling seller of matches and tinder who fell ill with jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme meta ...

at Hare's lodging house. As with Joseph, Hare was concerned with the effect this illness might have on his business, and he and Burke employed the same ''modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of o ...

'' they had with the miller: Hare suffocating their victim while Burke lay over the body to stop movement and noise. Simpson was a pensioner who lived in the nearby village of Gilmerton

Gilmerton ( gd, Baile GhilleMhoire, IPA: �paləˈʝiːʎəˈvɔɾʲə is a suburb of Edinburgh, about southeast of the city centre.

The toponym "Gilmerton" is derived from a combination of gd, Gille-Moire– a personal name and later surnam ...

and visited Edinburgh to supplement her pension by selling salt. On 12 February 1828—the only exact date Burke quoted in his confession—she was invited into the Hares' house and plied with enough alcohol to ensure she was too drunk to return home. After murdering her, Burke and Hare placed the body in a tea-chest and sold it to Knox. They received £10 for each body, and Burke's confession records of Simpson's body that "Dr Knox approved of its being so fresh ... but edid not ask any questions". In either February or March that year an old woman was invited into the house by Margaret Hare. She gave her enough whisky to fall asleep, and when Hare returned that afternoon, he covered the sleeping woman's mouth and nose with the bed tick (a stiff mattress cover) and left her. She was dead by nightfall and Burke joined his companion to transport the corpse to Knox, who paid another £10.

Burke met two women in early April: Mary Paterson (also known as Mary Mitchell) and Janet Brown, in the Canongate area of Edinburgh. He bought the two women alcohol before inviting them back to his lodging for breakfast. The three left the tavern with two bottles of whisky and went instead to his brother Constantine's house. After his brother left for work, Burke and the women finished the whisky and Paterson fell asleep at the table; Burke and Brown continued talking but were interrupted by McDougal, who accused them of having an affair. A row broke out between Burke and McDougal—during which he threw a glass at her, cutting her over the eye—Brown stated that she did not know Burke was married and left; McDougal also left, and went to fetch Hare and his wife. They arrived shortly afterwards and the two men locked their wives out of the room, then murdered Paterson in her sleep. That afternoon the pair took the body to Knox in a tea-chest, while McDougal kept Paterson's skirt and petticoats; they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it. Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate". Knox was delighted with the corpse, and stored it in whisky for three months before dissecting it. When Brown later searched for her friend, she was told that she had left for

Burke met two women in early April: Mary Paterson (also known as Mary Mitchell) and Janet Brown, in the Canongate area of Edinburgh. He bought the two women alcohol before inviting them back to his lodging for breakfast. The three left the tavern with two bottles of whisky and went instead to his brother Constantine's house. After his brother left for work, Burke and the women finished the whisky and Paterson fell asleep at the table; Burke and Brown continued talking but were interrupted by McDougal, who accused them of having an affair. A row broke out between Burke and McDougal—during which he threw a glass at her, cutting her over the eye—Brown stated that she did not know Burke was married and left; McDougal also left, and went to fetch Hare and his wife. They arrived shortly afterwards and the two men locked their wives out of the room, then murdered Paterson in her sleep. That afternoon the pair took the body to Knox in a tea-chest, while McDougal kept Paterson's skirt and petticoats; they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it. Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate". Knox was delighted with the corpse, and stored it in whisky for three months before dissecting it. When Brown later searched for her friend, she was told that she had left for Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

with a travelling salesman.

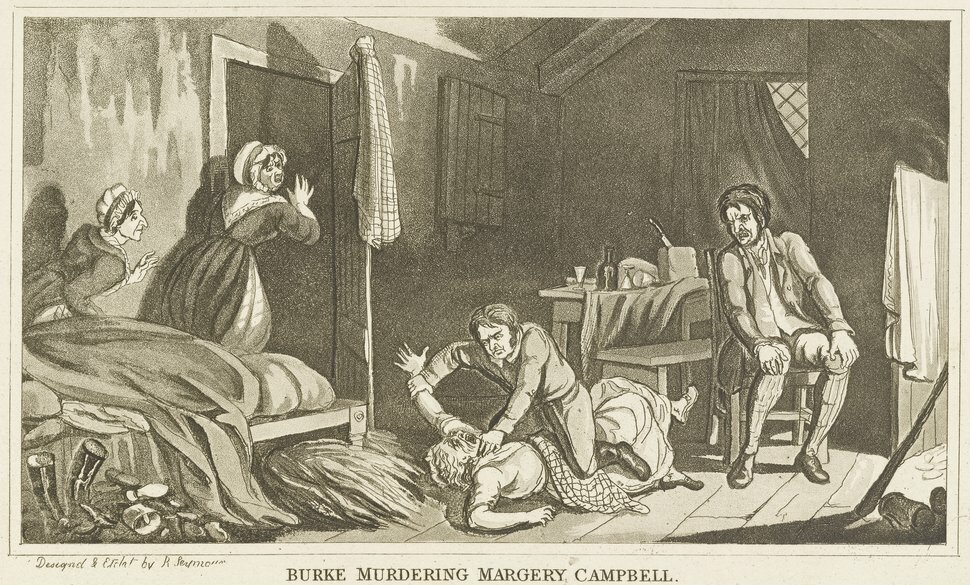

At some point in early-to-mid 1828 a Mrs Haldane, whom Burke described as "a stout old woman", lodged at Hare's premises. After she became drunk, she fell asleep in the stable; she was smothered and sold to Knox. Several months later Haldane's daughter (either called Margaret or Peggy) also lodged at Hare's house. She and Burke drank together heavily and he killed her, without Hare's assistance; her body was put into a tea-chest and taken to Knox where Burke was paid £8. The next murder occurred in May 1828, when an old woman joined the house as a lodger. One evening while she was intoxicated, Burke smothered her—Hare was not present in the house at the time; her body was sold to Knox for £10. Then came the murder of Effy (sometimes spelt Effie), a "cinder gatherer" who scavenged through bins and rubbish tips to sell her findings. Effy was known to Burke and had previously sold him scraps of leather for his cobbling business. Burke tempted her into the stable with whisky, and when she was drunk enough he and Hare killed her; Knox gave £10 for the body. Another victim was found by Burke too drunk to stand. She was being helped by a local constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

back to her lodgings when Burke offered to take her there himself; the policeman obliged, and Burke took her back to Hare's house where she was killed. Her corpse raised a further £10 from Knox.

Burke and Hare murdered two lodgers in June, "an old woman and a dumb boy, her grandson", as Burke later recalled in his confession. While the boy sat by the fire in the kitchen, his grandmother was murdered in the bedroom by the usual method. Burke and Hare then picked up the boy and carried him to the same room where he was also killed. Burke later said that this was the murder that disturbed him the most, as he was haunted by his recollection of the boy's expression. The tea-chest that was usually used by the duo to transport the bodies was found to be too small, so the bodies were forced into a herring barrel and taken to Surgeons' Square, where they fetched £8 each. According to Burke's confession, the barrel was loaded onto a cart which Hare's horse refused to pull further than the Grassmarket. Hare called a porter with a handcart to help him transport the container. Once back in Tanner's Close, Hare took his anger out on the horse by shooting it dead in the yard.

On 24 June Burke and McDougal departed for Falkirk to visit the latter's father. Burke knew that Hare was short of cash and had even pawned some of his clothes. When the couple returned, they found that Hare was wearing new clothes and had surplus money. After he was asked, Hare denied that he had sold another body. Burke checked with Knox, who confirmed Hare had sold a woman's body for £8. It led to an argument between the two men and they came to blows. Burke and his wife moved into the home of his cousin, John Broggan (or Brogan), two streets away from Tanner's Close.

The breach between the two men did not last long. In late September or early October Hare was visiting Burke when Mrs Ostler (also given as Hostler), a washerwoman, came to the property to do the laundry. The men got her drunk and killed her; the corpse was with Knox that afternoon, for which the men received £8. A week or two later one of McDougal's relatives, Ann Dougal (also given as McDougal) was visiting from Falkirk; after a few days the men killed her by their usual technique and received £10 for the body. Burke later claimed that about this time Hare's wife suggested killing Helen McDougal on the grounds that "they could not trust her, as she was a Scotch woman", but he refused.

Burke and Hare's next victim was a familiar figure in the streets of Edinburgh: James Wilson, an 18-year-old man with a limp caused by deformed feet. He was mentally disabled and, according to Alanna Knight in her history of the murders, was inoffensive; he was known locally as Daft Jamie. Wilson lived on the streets and supported himself by begging. In November Hare lured Wilson to his lodgings with the promise of whisky, and sent his wife to fetch Burke. The two murderers led Wilson into a bedroom, the door of which Margaret locked before pushing the key back under the door. As Wilson did not like excess whisky—he preferred snuff—he was not as drunk as most of the duo's victims; he was also strong and fought back against the two attackers, but was overpowered and killed in the normal way. His body was stripped and his few possessions stolen: Burke kept a snuff box and Hare a snuff spoon. When the body was examined the following day by Knox and his students, several of them recognised it to be Wilson, but Knox denied it could be anyone the students knew. When word started circulating that Wilson was missing, Knox dissected the body ahead of the others that were being held in storage; the head and feet were removed before the main dissection.

The final victim, killed on 31 October 1828, was Margaret Docherty, a middle-aged Irish woman. Burke lured her into the Broggan lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of McDougal while he went out, ostensibly to buy more whisky, but actually to get Hare. Two other lodgers—Ann and James Gray—were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare's lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret had joined in. At around 9:00 pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Although Burke and Hare came to blows at some point in the evening, they subsequently murdered Docherty, and put her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty's body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into McDougal who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week; they refused. While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox's surgery. The police search located Docherty's bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed. When questioned, Burke and his wife claimed that Docherty had left the house, but gave different times for her departure. This raised enough suspicion for the police to take them in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox's dissecting-rooms where they found Docherty's body; James identified her as the woman he had seen with Burke and Hare. Hare and his wife were arrested that day, as was Broggan; all denied any knowledge of the events.

In total sixteen people were murdered by Burke and Hare. Burke stated later that he and Hare were "generally in a state of intoxication" when the murders were carried out, and that he "could not sleep at night without a bottle of whisky by his bedside, and a twopenny candle to burn all night beside him; when he awoke he would take a drink from the bottle—sometimes half a bottle at a draught—and that would make him sleep." He also took

The final victim, killed on 31 October 1828, was Margaret Docherty, a middle-aged Irish woman. Burke lured her into the Broggan lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of McDougal while he went out, ostensibly to buy more whisky, but actually to get Hare. Two other lodgers—Ann and James Gray—were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare's lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret had joined in. At around 9:00 pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Although Burke and Hare came to blows at some point in the evening, they subsequently murdered Docherty, and put her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty's body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into McDougal who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week; they refused. While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox's surgery. The police search located Docherty's bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed. When questioned, Burke and his wife claimed that Docherty had left the house, but gave different times for her departure. This raised enough suspicion for the police to take them in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox's dissecting-rooms where they found Docherty's body; James identified her as the woman he had seen with Burke and Hare. Hare and his wife were arrested that day, as was Broggan; all denied any knowledge of the events.

In total sixteen people were murdered by Burke and Hare. Burke stated later that he and Hare were "generally in a state of intoxication" when the murders were carried out, and that he "could not sleep at night without a bottle of whisky by his bedside, and a twopenny candle to burn all night beside him; when he awoke he would take a drink from the bottle—sometimes half a bottle at a draught—and that would make him sleep." He also took opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

to ease his conscience.

Developments: investigation and the path to court

On 3 November 1828 a warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives; Broggan was released without further action. The four suspects were kept apart and statements taken; these conflicted with the initial answers given on the day of their arrests. After Alexander Black, a police surgeon, examined Docherty's body, two forensic specialists were appointed, Robert Christison and William Newbigging; they reported that it was probable the victim had been murdered by suffocation, but this could not be medically proven. On the basis of the report from the two doctors, the Burkes and Hares were charged with murder. As part of his investigation Christison interviewed Knox, who asserted that Burke and Hare had watched poor lodging houses in Edinburgh and purchased bodies before anyone claimed them for burial. Christison thought Knox was "deficient in principle and heart", but did not think he had broken the law.

Although the police were sure murder had taken place, and that at least one of the four was guilty, they were uncertain whether they could secure a conviction. Police also suspected there had been other murders committed, but the lack of bodies hampered this line of enquiry. As news of the possibility of other murders came to the public's attention, newspapers began to publish lurid and inaccurate stories of the crimes; speculative reports led members of the public to assume that all missing people had been victims. Janet Brown went to the police and identified her friend Mary Paterson's clothing, while a local baker informed them that Jamie Wilson's trousers were being worn by Burke's nephew. On 19 November a warrant for the murder of Jamie Wilson was made against the four suspects.

Sir William Rae, the

On 3 November 1828 a warrant was issued for the detention of Burke, Hare and their wives; Broggan was released without further action. The four suspects were kept apart and statements taken; these conflicted with the initial answers given on the day of their arrests. After Alexander Black, a police surgeon, examined Docherty's body, two forensic specialists were appointed, Robert Christison and William Newbigging; they reported that it was probable the victim had been murdered by suffocation, but this could not be medically proven. On the basis of the report from the two doctors, the Burkes and Hares were charged with murder. As part of his investigation Christison interviewed Knox, who asserted that Burke and Hare had watched poor lodging houses in Edinburgh and purchased bodies before anyone claimed them for burial. Christison thought Knox was "deficient in principle and heart", but did not think he had broken the law.

Although the police were sure murder had taken place, and that at least one of the four was guilty, they were uncertain whether they could secure a conviction. Police also suspected there had been other murders committed, but the lack of bodies hampered this line of enquiry. As news of the possibility of other murders came to the public's attention, newspapers began to publish lurid and inaccurate stories of the crimes; speculative reports led members of the public to assume that all missing people had been victims. Janet Brown went to the police and identified her friend Mary Paterson's clothing, while a local baker informed them that Jamie Wilson's trousers were being worn by Burke's nephew. On 19 November a warrant for the murder of Jamie Wilson was made against the four suspects.

Sir William Rae, the Lord Advocate

His Majesty's Advocate, known as the Lord Advocate ( gd, Morair Tagraidh, sco, Laird Advocat), is the chief legal officer of the Scottish Government and the Crown in Scotland for both civil and criminal matters that fall within the devolved p ...

, followed a regular technique: he focused on one individual to extract a confession on which the others could be convicted. Hare was chosen and, on 1 December, he was offered immunity from prosecution

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Su ...

if he turned king's evidence and provided the full details of the murder of Docherty and any other; because he could not be brought to testify against his wife, she was also exempt from prosecution. Hare made a full confession of all the deaths and Rae decided sufficient evidence existed to secure a prosecution. On 4 December formal charges were laid against Burke and McDougal for the murders of Mary Paterson, James Wilson and Mrs Docherty.

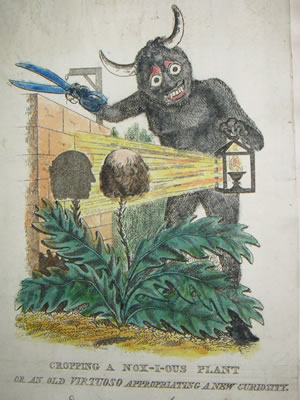

Knox faced no charges for the murders because Burke's statement to the police exonerated the surgeon. Public awareness of the news grew as newspapers and broadsides began releasing further details. Opinion was against Knox and, according to Bailey, many in Edinburgh thought he was "a sinister ringmaster who got Burke and Hare dancing to his tune". Several broadsides were published with editorials stating that he should have been in the dock alongside the murderers, which influenced public opinion. A new word was coined from the murders: '' burking'', to smother a victim or to commit an

Knox faced no charges for the murders because Burke's statement to the police exonerated the surgeon. Public awareness of the news grew as newspapers and broadsides began releasing further details. Opinion was against Knox and, according to Bailey, many in Edinburgh thought he was "a sinister ringmaster who got Burke and Hare dancing to his tune". Several broadsides were published with editorials stating that he should have been in the dock alongside the murderers, which influenced public opinion. A new word was coined from the murders: '' burking'', to smother a victim or to commit an anatomy murder

An anatomy murder (sometimes called burking in British English) is a murder committed in order to use all or part of the cadaver for medical research or teaching. It is not a medicine murder because the body parts are not believed to have any medi ...

, and a rhyme began circulating around the streets of Edinburgh:

Trial

The trial began at 10:00 am on Christmas Eve 1828 before theHigh Court of Justiciary

The High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The High Court is both a trial court and a court of appeal. As a trial court, the High Court sits on circuit at Parliament House or in the adjacent former Sheriff Cour ...

in Edinburgh's Parliament House. The case was heard by the Lord Justice-Clerk, David Boyle, supported by the Lords Meadowbank, Pitmilly and Mackenzie. The court was full shortly after the doors were opened at 9:00 am, and a large crowd gathered outside Parliament House; 300 constables were on duty to prevent disturbances, while infantry and cavalry were on standby as a further precaution.

The case ran through the day and night to the following morning; Rosner notes that even a formal postponement of the case for dinner could have raised questions about the validity of the trial. When the charges were read out, the two defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

counsels objected to Burke and McDougal being tried together. James Moncreiff, Burke's defence lawyer, protested that his client was charged "with three unconnected murders, committed each at a different time, and at a different place" in a trial with another defendant "who is not even alleged to have had any concern with two of the offences of which he is accused". Several hours were spent on legal arguments about the objection. The judge decided that to ensure a fair trial, the indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that ...

should be split into separate charges for the three murders. He gave Rae the choice as to which should be heard first; Rae opted for the murder of Docherty, given they had the corpse and the strongest evidence.

In the early afternoon Burke and McDougal pleaded not guilty to the murder of Docherty. The first witnesses were then called from a list of 55 that included Hare and Knox; not all the witnesses on the list were called and Knox, with three of his assistants, avoided being questioned in court. One of Knox's assistants, David Paterson—who had been the main person Burke and Hare had dealt with at Knox's surgery—was called and confirmed the pair had supplied the doctor with several corpses.

In the early evening Hare took the stand to give evidence. Under cross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

about the murder of Docherty, Hare claimed Burke had been the sole murderer and McDougal had twice been involved by bringing Docherty back to the house after she had run out; Hare stated that he had assisted Burke in the delivery of the body to Knox. Although he was asked about other murders, he was not obliged to answer the questions, as the charge related only to the death of Docherty. After Hare's questioning, his wife entered the witness box, carrying their baby daughter who had developed whooping cough

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or t ...

. Margaret used the child's coughing fits as a way to give herself thinking time for some of the questions, and told the court that she had a very poor memory and could not remember many of the events.

The final prosecution witnesses were the two doctors, Black and Christison; both said they suspected foul play, but that there was no forensic evidence to support the suggestion of murder. There were no witnesses called for the defence, although the pre-trial declarations by Burke and McDougal were read out in their place. The prosecution summed up their case, after which, at 3:00 am, Burke's defence lawyer began his final statement, which lasted for two hours; McDougal's defence lawyer began his address to the jury on his client's behalf at 5:00 am. Boyle then gave his summing up, directing the jury to accept the arguments of the prosecution. The jury retired to consider its verdict at 8:30 am on Christmas Day and returned fifty minutes later. It delivered a guilty verdict against Burke for the murder of Docherty; the same charge against McDougal they found not proven. As he passed the death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

against Burke, Boyle told him:

Aftermath, including execution and dissection

McDougal was released at the end of the trial and returned home. The following day she went to buy whisky and was confronted by a mob who were angry at the not proven verdict. She was taken to a police building in nearby Fountainbridge for her own protection, but after the mob laid siege to it she escaped through a back window to the main police station off Edinburgh's High Street. She tried to see Burke, but permission was refused; she left Edinburgh the next day, and there are no clear accounts of her later life. On 3 January 1829, on the advice of both Catholic priests and Presbyterian clergy, Burke made another confession. This was more detailed than the official one provided prior to his trial; he placed much of the blame for the murders on Hare.

On 16 January 1829 a

McDougal was released at the end of the trial and returned home. The following day she went to buy whisky and was confronted by a mob who were angry at the not proven verdict. She was taken to a police building in nearby Fountainbridge for her own protection, but after the mob laid siege to it she escaped through a back window to the main police station off Edinburgh's High Street. She tried to see Burke, but permission was refused; she left Edinburgh the next day, and there are no clear accounts of her later life. On 3 January 1829, on the advice of both Catholic priests and Presbyterian clergy, Burke made another confession. This was more detailed than the official one provided prior to his trial; he placed much of the blame for the murders on Hare.

On 16 January 1829 a petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to some offi ...

on behalf of James Wilson's mother and sister, protesting against Hare's immunity and intended release from prison, was given lengthy consideration by the High Court of Justiciary and rejected by a vote of 4 to 2. Margaret was released on 19 January and travelled to Glasgow to find a passage back to Ireland. While waiting for a ship she was recognised and attacked by a mob. She was given shelter in a police station before being given a police escort onto a Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

-bound vessel; no clear accounts exist of what became of her after she landed in Ireland.

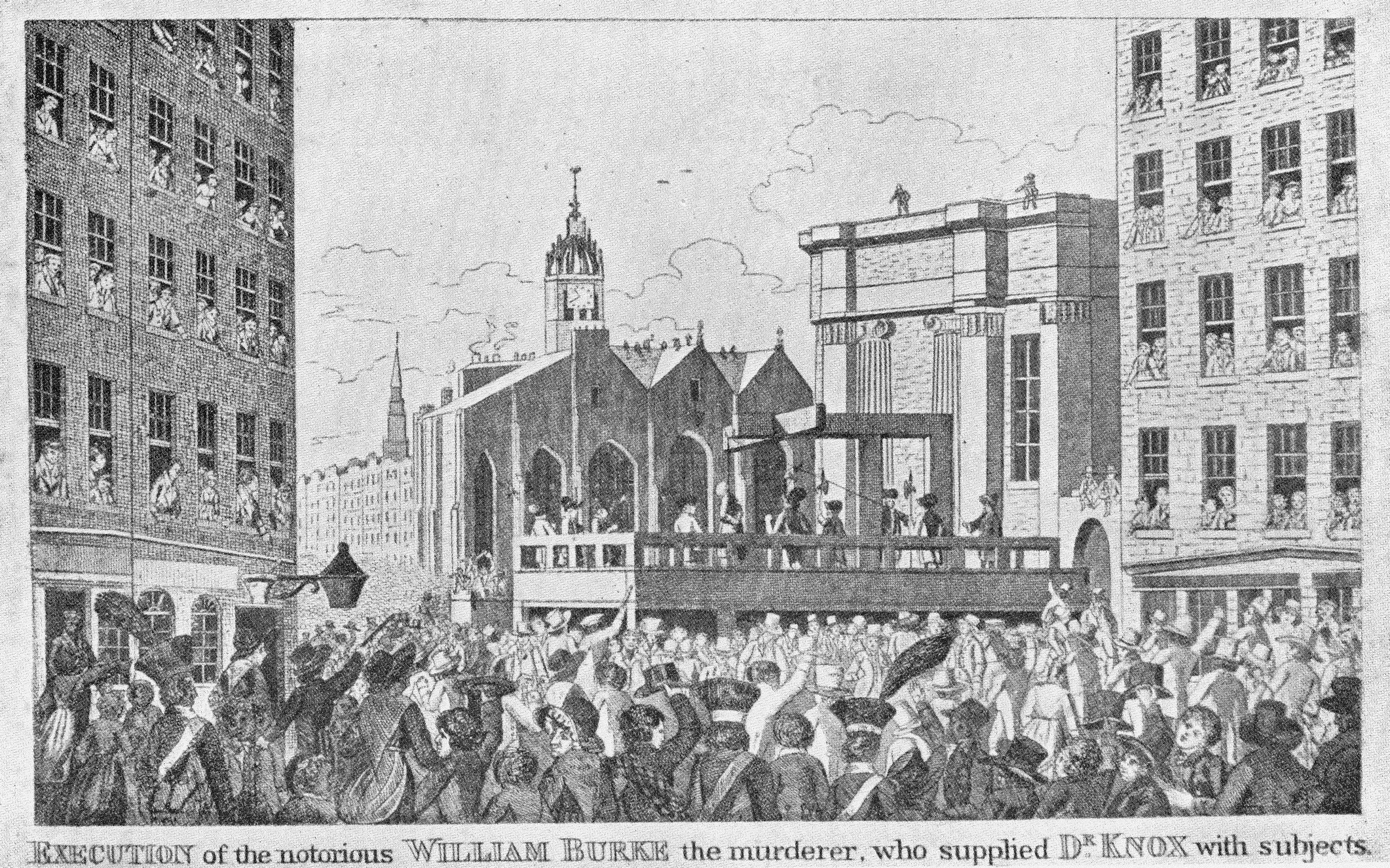

Burke was

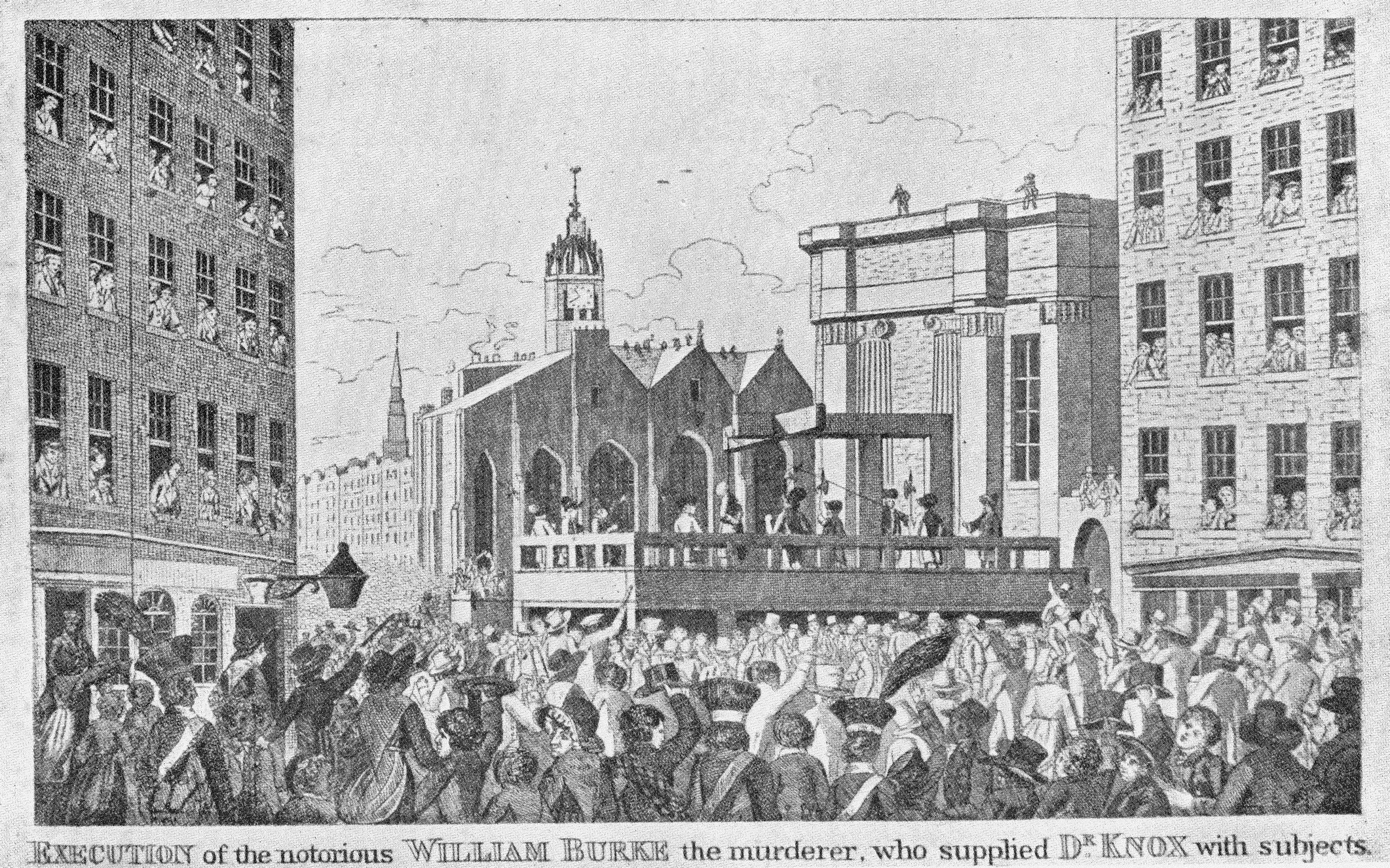

Burke was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The '' Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

on the morning of 28 January 1829 in front of a crowd possibly as large as 25,000; views from windows in the tenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, i ...

s overlooking the scaffold were hired at prices ranging from 5s to 20s. On 1 February Burke's corpse was publicly dissected by Professor Monro in the anatomy theatre of the university's Old College. Police had to be called when large numbers of students gathered demanding access to the lecture for which a limited number of tickets had been issued. A minor riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

ensued; calm was restored only after one of the university professors negotiated with the crowd that they would be allowed to pass through the theatre in batches of fifty, after the dissection. During the procedure, which lasted for two hours, Monro dipped his quill pen into Burke's blood and wrote, "This is written with the blood of Wm Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh. This blood was taken from his head".

Burke's skeleton was given to the Anatomical Museum of the Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine. It was es ...

where, , it remains. His death mask and a book said to be bound with his tanned skin can be seen at Surgeons' Hall Museum.

Hare was released on 5 February 1829—his extended stay in custody had been undertaken for his own protection—and was assisted in leaving Edinburgh in disguise by the mailcoach to Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from t ...

. At one of its stops he was recognised by a fellow passenger, Erskine Douglas Sandford

Erskine Douglas Sandford FRSE (31 July 1793–4 September 1861) was a 19th-century Scottish advocate and legal author.

Life

He was born at 22 South Frederick Street in Edinburgh's New Town, then a new house, on 31 July 1793 the son of Helen F ...

, a junior counsel who had represented Wilson's family; Sandford informed his fellow passengers of Hare's identity. On arrival in Dumfries the news of Hare's presence spread and a large crowd gathered at the hostelry where he was due to stay the night. Police arrived and arranged for a decoy coach to draw off the crowd while Hare escaped through a back window and into a carriage which took him to the town's prison for safekeeping. A crowd surrounded the building; stones were thrown at the door and windows and street lamps were smashed before 100 special constables arrived to restore order. In the small hours of the morning, escorted by a sheriff officer and militia guard, Hare was taken out of town, set down on the Annan Road and instructed to make his way to the English border. There were no subsequent reliable sightings of him and his eventual fate is unknown.

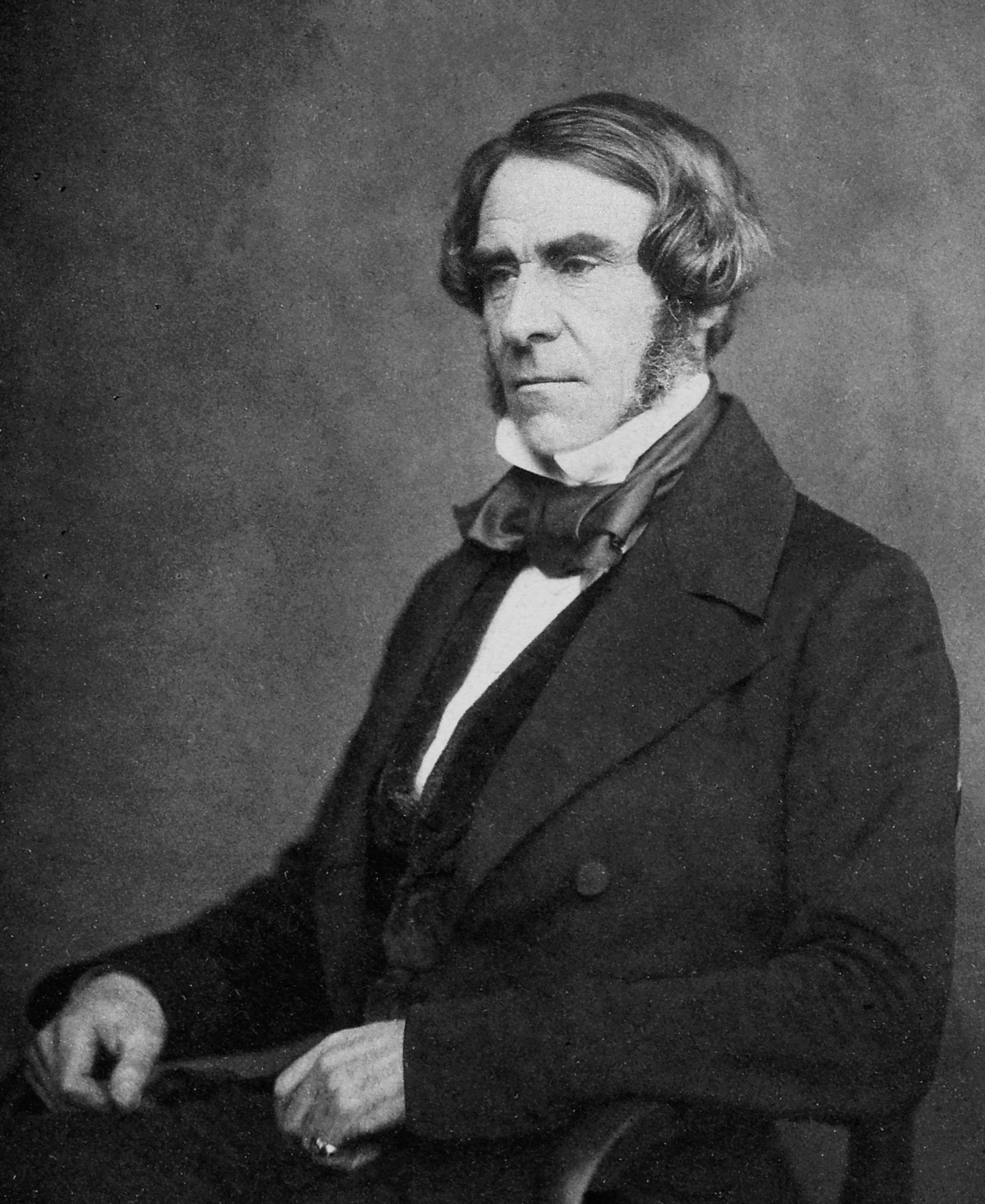

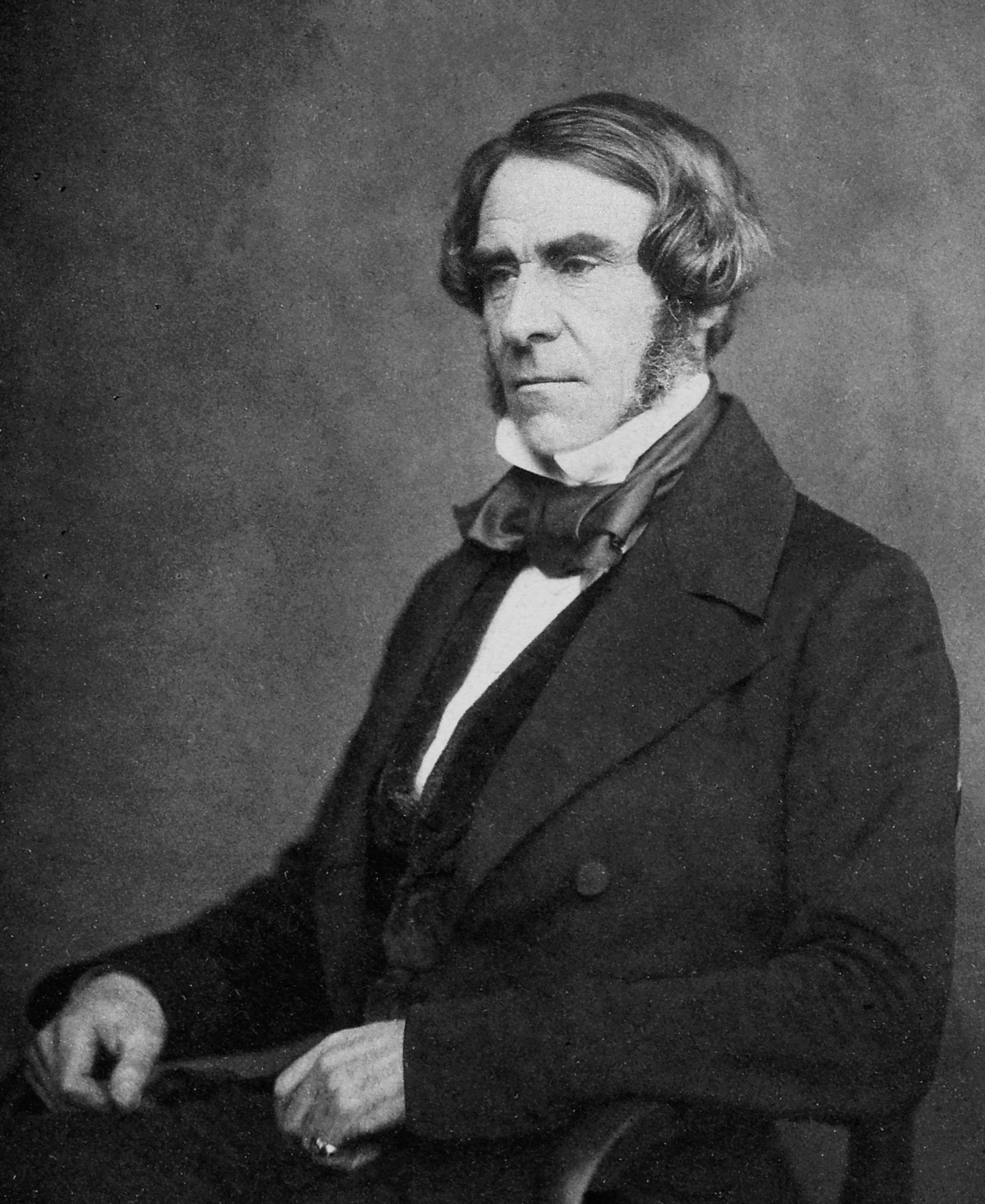

Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare. The common thought in Edinburgh was that he was culpable in the events; he was lampooned in caricature and, in February 1829, a crowd gathered outside his house and burned an effigy of him. A committee of inquiry cleared him of complicity and reported that they had "seen no evidence that Dr Knox or his assistants knew that murder was committed in procuring any of the subjects brought to his rooms". He resigned from his position as curator of the College of Surgeons' museum, and was gradually excluded from university life by his peers. He left Edinburgh in 1842 and lectured in Britain and mainland Europe. While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the

Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare. The common thought in Edinburgh was that he was culpable in the events; he was lampooned in caricature and, in February 1829, a crowd gathered outside his house and burned an effigy of him. A committee of inquiry cleared him of complicity and reported that they had "seen no evidence that Dr Knox or his assistants knew that murder was committed in procuring any of the subjects brought to his rooms". He resigned from his position as curator of the College of Surgeons' museum, and was gradually excluded from university life by his peers. He left Edinburgh in 1842 and lectured in Britain and mainland Europe. While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

and was debarred from lecturing; he was removed from the roll of fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1848. From 1856 he worked as a pathological anatomist at the Brompton Cancer Hospital and had a medical practice in Hackney until his death in 1862.

Legacy

Legislation

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 February 1747– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundam ...