British space programme on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The British space programme is the British government's work to develop British

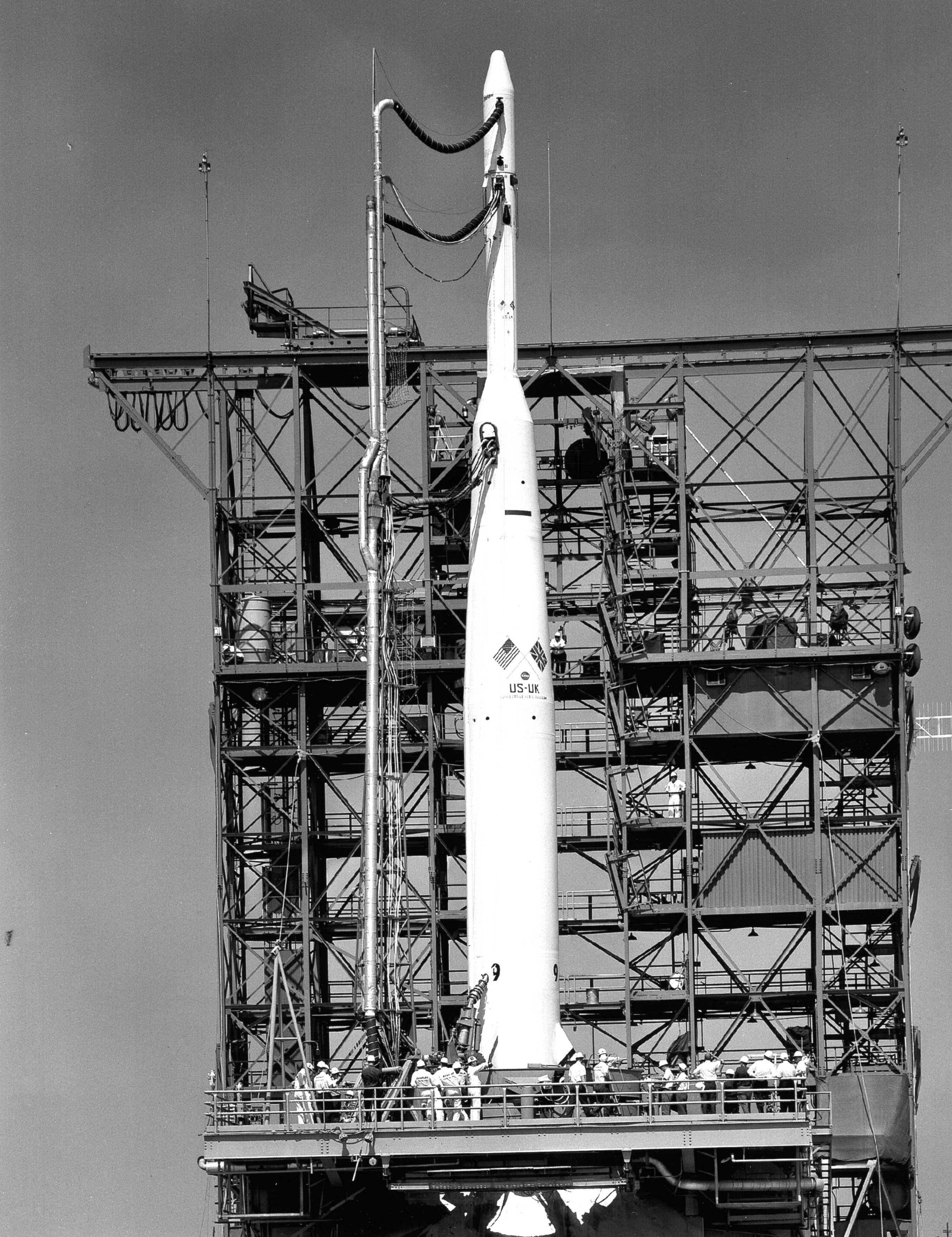

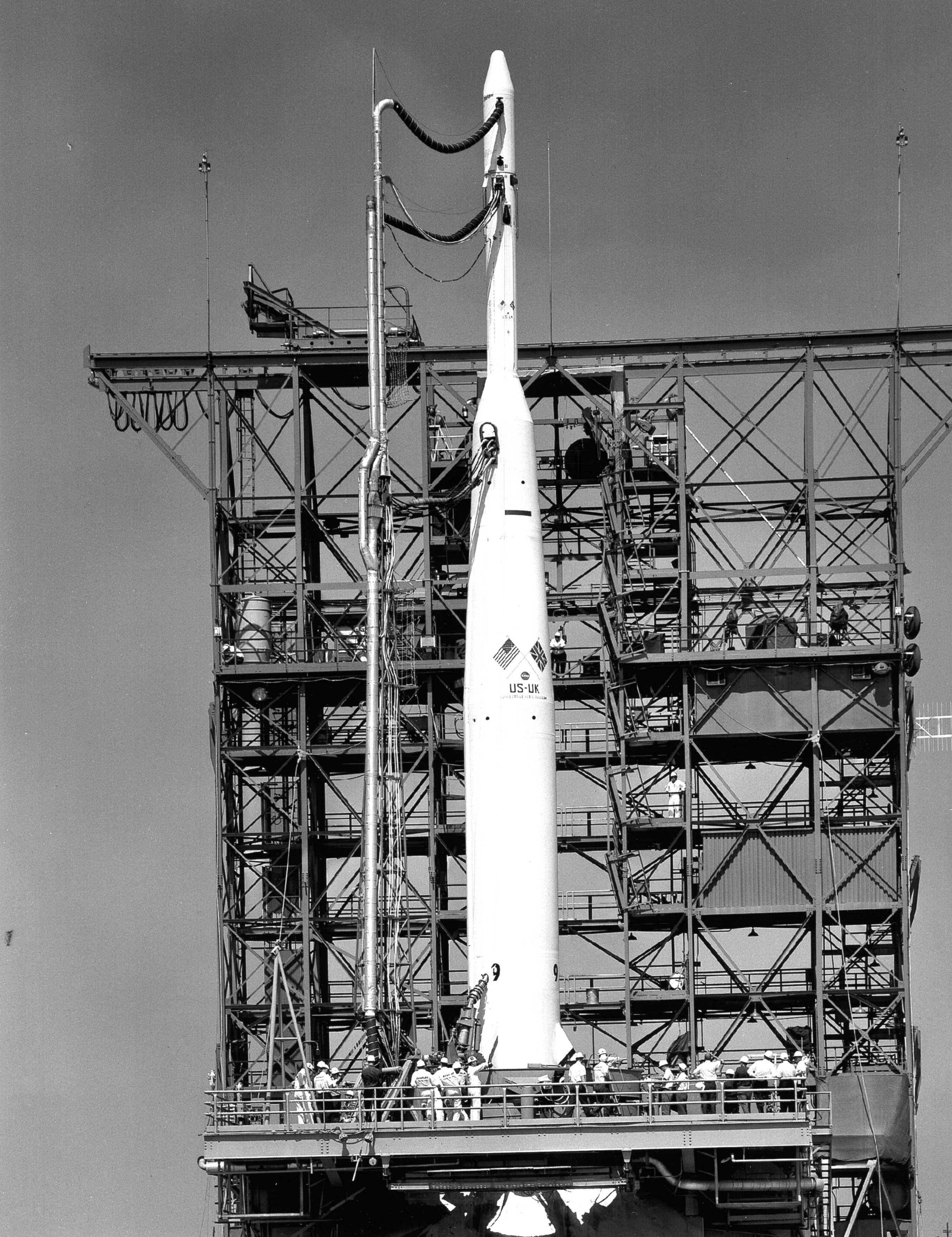

The Ariel programme developed six satellites between 1962 and 1979, all of which were launched by

The Ariel programme developed six satellites between 1962 and 1979, all of which were launched by

Beginning in 1950, the UK developed and launched several space rockets, as well as developing space planes. These included the '' Black Knight'' and '' Blue Streak'' rockets. During this period, the launcher programmes were administered in succession by the Ministry of Supply, the Ministry of Aviation, the

Beginning in 1950, the UK developed and launched several space rockets, as well as developing space planes. These included the '' Black Knight'' and '' Blue Streak'' rockets. During this period, the launcher programmes were administered in succession by the Ministry of Supply, the Ministry of Aviation, the

In 1985, the British National Space Centre (BNSC) was formed to coordinate British space activities. The BNSC was a significant contributor to the general budget of the

In 1985, the British National Space Centre (BNSC) was formed to coordinate British space activities. The BNSC was a significant contributor to the general budget of the

On 1 April 2010, the

On 1 April 2010, the

Project Juno was a privately funded campaign, which selected Helen Sharman to be the first Briton in space. A private consortium was formed to raise money to pay the USSR for a seat on a

Project Juno was a privately funded campaign, which selected Helen Sharman to be the first Briton in space. A private consortium was formed to raise money to pay the USSR for a seat on a

UK Space Agency

*

Rocketeers.co.uk

– UK space news blog *

Virgin Galactic

UK made 'fundamental space mistake'

BBC Report on SST

BBC, 24 March 2011

article on recent UK government announcement contrasted with recent French government funding increases. ;Other resources * Hill, C.N., ''A Vertical Empire: The History of the UK Rocket and Space Programme, 1950–1971'' * Millard, Douglas,

An Overview of United Kingdom Space Activity 1957–1987

', ESA Publications. * Erik Seedhouse: ''Tim Peake and Britains's road to space.'' Springer, Cham 2017, . {{DEFAULTSORT:British Space Programme Cold War missiles of the United Kingdom Programmes of the Government of the United Kingdom Space research 1952 establishments in the United Kingdom

space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

capabilities. The objectives of the current civil programme are to "win sustainable economic growth, secure new scientific knowledge and provide benefits to all citizens."

The first official British space programme began in 1952. In 1959, the first satellite programme was started, with the Ariel series of British satellites, built in the United States and the UK and launched using American rockets. The first British satellite, Ariel 1, was launched in 1962. The British space programme has always emphasized uncrewed space research and commercial initiatives. It has never been government policy to create a British astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

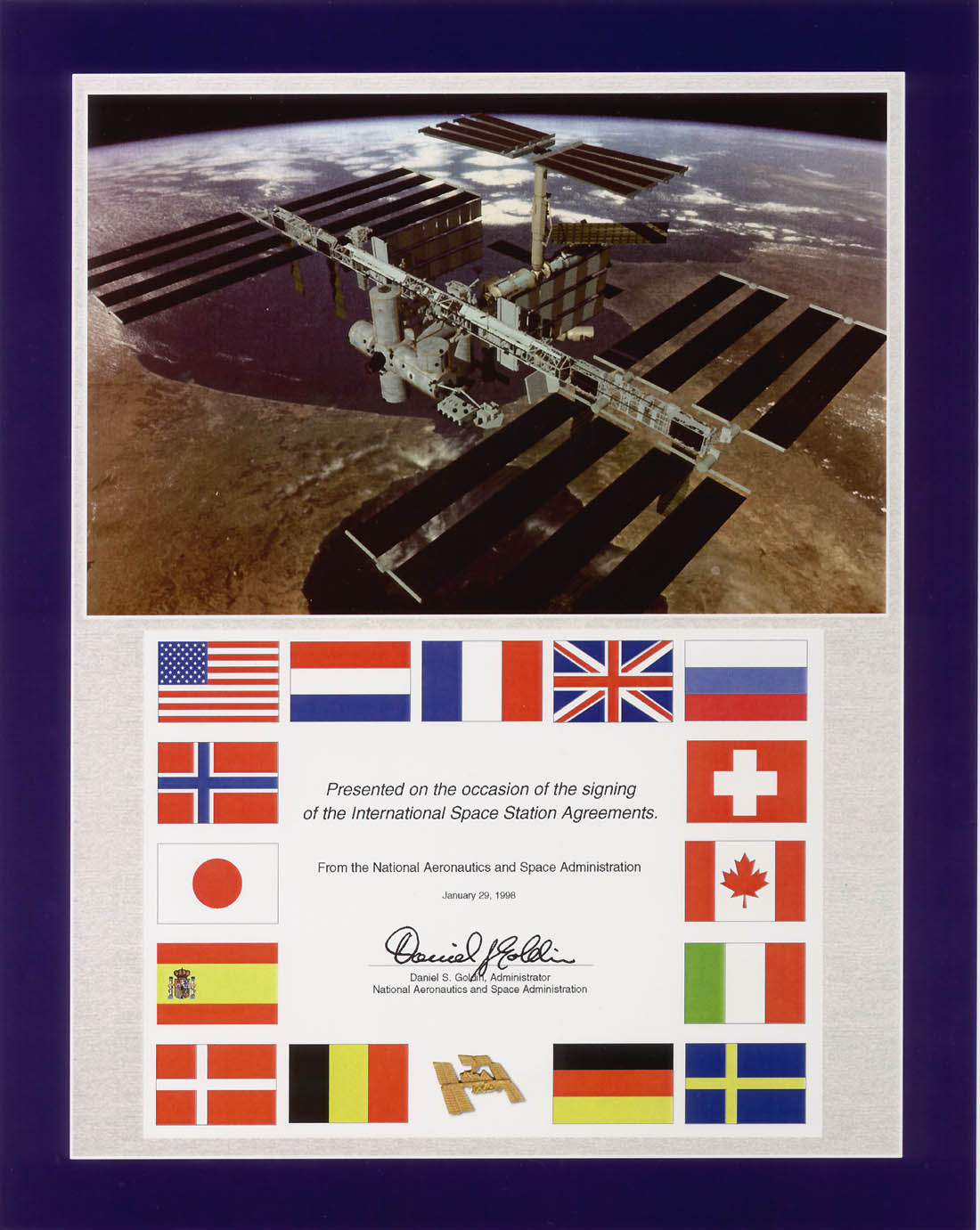

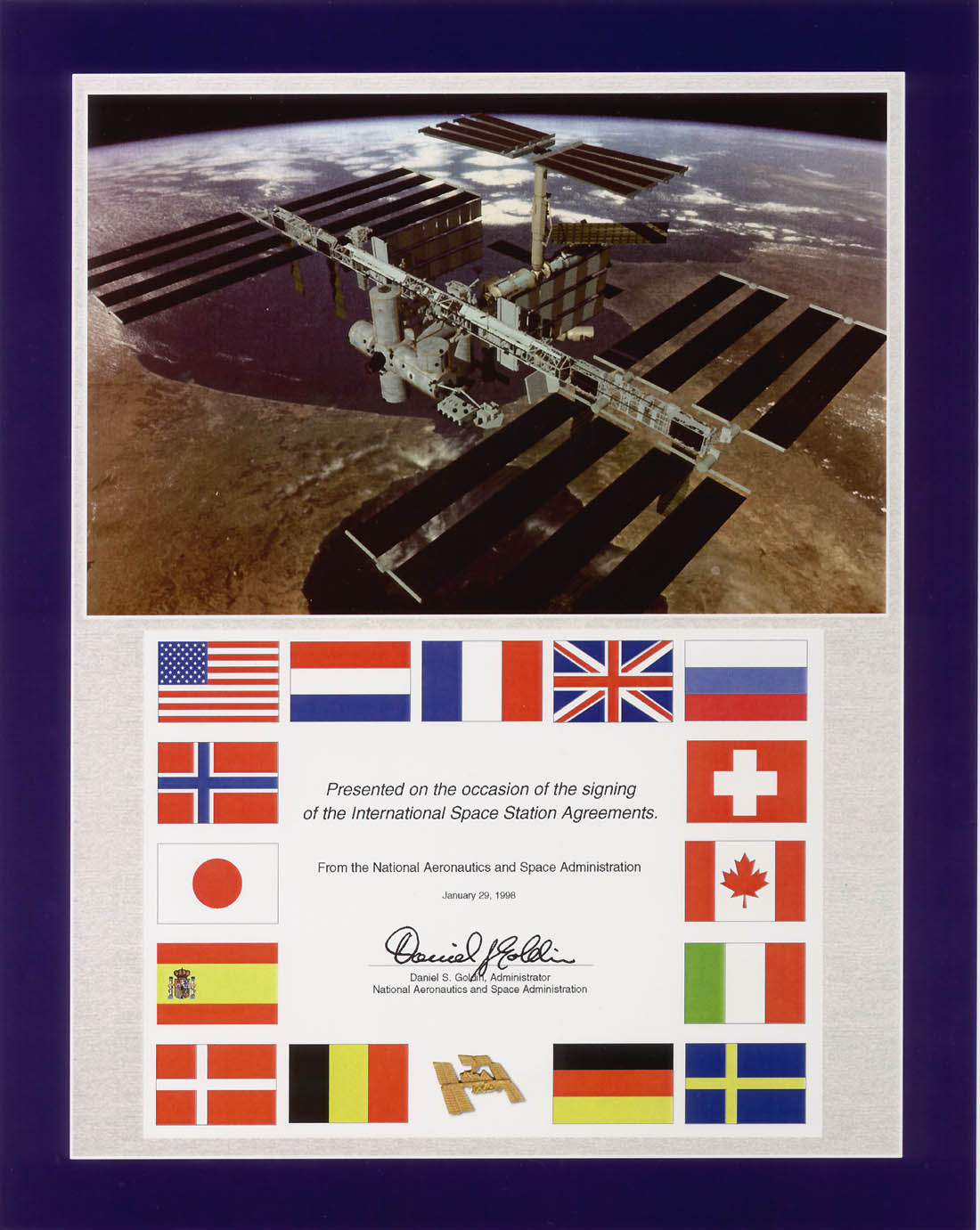

corps. The British government did not provide funding for the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a large space station that was Assembly of the International Space Station, assembled and is maintained in low Earth orbit by a collaboration of five space agencies and their contractors: NASA (United ...

until 2011.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a number of efforts were made to develop a British satellite launch capability. A British rocket named Black Arrow placed a single British satellite, Prospero, into orbit from a launch site in Australia in 1971. Prospero remains the only British satellite to be put into orbit using a British vehicle.

The British National Space Centre was established in 1985 to coordinate British government agencies and other interested bodies in the promotion of British participation in the international market for satellite launches, satellite construction and other space endeavours. In 2010, many of the various separate sources of space-related funding were combined and allocated to the centre's replacement, the UK Space Agency

The United Kingdom Space Agency (UKSA) is an executive agency of the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the United Kingdom's British space programme, civil space programme. It was established on 1 April 2010 to replace the Britis ...

. Among other projects, the agency funded a single-stage-to-orbit

A single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) vehicle reaches orbit from the surface of a body using only propellants and fluids and without expending tanks, engines, or other major hardware. The term usually, but not exclusively refers to reusable launch sys ...

spaceplane

A spaceplane is a vehicle that can flight, fly and gliding flight, glide as an aircraft in Earth's atmosphere and function as a spacecraft in outer space. To do so, spaceplanes must incorporate features of both aircraft and spacecraft. Orbit ...

concept called Skylon, which did not progress beyond testing of engine components.

Origins

Scientific interest in space travel existed in the United Kingdom prior toWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, particularly amongst members of the British Interplanetary Society (founded in 1933) whose members included Sir Arthur C. Clarke, author and conceiver of the geostationary telecommunications satellite, who joined the BIS before World War II.

As with the other post-war space-faring nations, the British government's initial interest in space was primarily military. Early programmes reflected this interest. As with other nations, much of the rocketry knowledge was obtained from captured German scientists who were persuaded to work for the British. The British performed the earliest post-war tests of captured V-2 rocket

The V2 (), with the technical name ''Aggregat (rocket family), Aggregat-4'' (A4), was the world's first long-range missile guidance, guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed during the S ...

s in Operation Backfire, less than six months after the end of the war in Europe. In 1946 a proposal was made by Ralph A. Smith to fund a British crewed suborbital launch in a modified V-2 called Megaroc; this was, however, rejected by the government.

From 1957, British space astronomy used Skylark suborbital sounding rockets, launched from Woomera, Australia, which at first reached heights of . Development of air-to-surface missiles such as Blue Steel contributed to progress towards launches of larger orbit-capable rockets.

History

British satellite programmes (1959–present)

Early satellite programmes

The Ariel programme developed six satellites between 1962 and 1979, all of which were launched by

The Ariel programme developed six satellites between 1962 and 1979, all of which were launched by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

.

In 1971, the last Black Arrow (R3) launched Prospero X-3, the only British satellite to be launched using a British rocket, from Australia. Ground contact with Prospero ended in 1996.

Military communications satellite programme

Skynet is a purely military programme, operating a set ofcommunications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a Transponder (satellite communications), transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a Rad ...

s on behalf of the Ministry of Defence (MoD), to provide communication services to the three branches of the British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces are the unified military, military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its British Overseas Territories, Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests ...

and to NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

and allied governments. The first satellite was launched in 1969, becoming the first military satellite in geostationary orbit

A geostationary orbit, also referred to as a geosynchronous equatorial orbit''Geostationary orbit'' and ''Geosynchronous (equatorial) orbit'' are used somewhat interchangeably in sources. (GEO), is a circular orbit, circular geosynchronous or ...

, and the most recent in 2012. As of 2020, seven Skynet satellites are operating and providing coverage of almost the whole globe.

Skynet is the most expensive British space project, although as a military initiative it is not part of the civil space programme. The MoD is currently specifying the Skynet 6 architecture to replace the Skynet 5 model satellites, which is expected to cost about £6 billion.

Intelligence satellite programmes

Zircon was thecodename

A code name, codename, call sign, or cryptonym is a code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may also be used in ...

for a British signals intelligence satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scient ...

, intended to be launched in 1988, but cancelled in 1987.

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, the UK's Government Communications Headquarters ( GCHQ) relied heavily on America's National Security Agency (NSA) for communications interception from space. GCHQ therefore decided to produce a British-designed-and-built signals intelligence satellite, to be named Zircon, a code-name derived from zirconium silicate, a diamond substitute. Zircon's function was to intercept radio and other signals from the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Europe and other areas. The satellite was to be built by Marconi Space and Defence Systems at Portsmouth Airport, where a high-security building had been built.

It was to be launched on a NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable launch system, reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. ...

under the guise of Skynet IV. Launch on the Shuttle would have entitled a British National to fly as a payload specialist, and a group of military pilots were presented to the press as candidates for ' Britain's first man in space'. Zircon was cancelled by Chancellor Nigel Lawson on cost grounds in 1987. The subsequent scandal about the true nature of the project became known as the Zircon affair.

Independent satellite navigation system

On 30 November 2018, it was announced that the United Kingdom Global Navigation Satellite System (UKGNSS) would not be affiliated with the European Space Agency's Galileo satellite system after Britain completed its withdrawal from the European Union. Instead, it was initially planned that theUK Space Agency

The United Kingdom Space Agency (UKSA) is an executive agency of the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the United Kingdom's British space programme, civil space programme. It was established on 1 April 2010 to replace the Britis ...

would operate an independent satellite system. However, on 25 September 2020, ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' reported that the United Kingdom Global Navigation Satellite System project had been scrapped. The project, deemed unnecessary and too expensive, would be replaced with a new project exploring alternative ways to provide satellite navigation services.

OneWeb satellite constellation

In July 2020, the United Kingdom government and India's Bharti Enterprises jointly purchased the bankrupt OneWeb satellite company, with the UK paying £400 million (US$500 million) for a 45% stake and a golden share to give it control over future ownership. The UK government was considering whether thelow Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an geocentric orbit, orbit around Earth with a orbital period, period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an orbital eccentricity, eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial object ...

OneWeb satellite constellation could in future provide a form of UKGNSS service in addition to its primary purpose of fast satellite broadband, and if it could be incorporated into the military Skynet 6 communications architecture. OneWeb satellites are manufactured by a joint venture including Airbus Defence and Space, who operate Skynet.

OneWeb commenced launches of the OneWeb satellite constellation, a network of more than 650 low Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an geocentric orbit, orbit around Earth with a orbital period, period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an orbital eccentricity, eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial object ...

satellites

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scientif ...

, in February 2019, and by March 2020, had launched 74 of the planned 648 satellites in the initial constellation. OneWeb's goal has been to provide internet services to "everyone, everywhere", delivering internet connections to rural and remote places as well as to a range of markets. The post-bankruptcy company leadership launched an additional 36 OneWeb satellites on 18 December 2020. OneWeb satellites are listed in the UK Registry of Outer Space Objects.

British space vehicles (1950–1985)

Ministry of Technology

The Ministry of Technology was a department of the government of the United Kingdom, sometimes abbreviated as "MinTech". The Ministry of Technology was established by the incoming government of Harold Wilson in October 1964 as part of Wilson's am ...

and the Department of Trade and Industry. Rockets were tested on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

, RAF Spadeadam, and Woomera in South Australia.

A major satellite launch vehicle was proposed in 1957 based on Blue Streak and Black Knight technology. This was named Black Prince, but the project was cancelled in 1960 due to lack of funding. Blue Streak rockets continued to be launched as the first stage of the European Europa carrier rocket until Europa's cancellation in 1972. The smaller '' Black Arrow'' launcher was developed from Black Knight and was first launched in 1969 from Woomera. The program was soon cancelled. In 1971, the last Black Arrow (R3) launched '' Prospero X-3'', becoming the first (and last) satellite to be placed in orbit by a British launch vehicle.

By 1972, British government funding of both Blue Streak and Black Arrow had ceased, and no further government-backed British space rockets were developed. Other space agencies, notably NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, were used for subsequent launches of British satellites. Communication with the Prospero X-3 was terminated in 1996.

'' Falstaff'', a British hypersonic test rocket, was launched from Woomera between 1969 and 1979.

In 1960 the British Space Development Company, a consortium of thirteen large industrial companies, was set up by Robert Renwick, 1st Baron Renwick to plan the world's first commercial communication satellite company, Renwick becoming the executive director. With Blue Streak, Britain had the technology to make it possible, but the idea was rejected by the British government on the grounds that such a system could not be envisaged in the next 20 years (1961–1981). The United States would eventually set up COMSAT in 1963, resulting in Intelsat

Intelsat S.A. (formerly Intel-Sat, Intelsat) is a Luxembourgish-American multinational satellite services provider with corporate headquarters in Luxembourg and administrative headquarters in Tysons, Virginia, United States. Originally formed ...

, a large fleet of commercial satellites. The first of Intelsat's fleet, Intelsat I, was launched in April 1965.

The official national space programme was revived in 1982 when the British government funded the HOTOL project, an ambitious attempt at a re-usable space plane using air-breathing rocket engines designed by Alan Bond. Work was begun by British Aerospace. However, having classified the engine design as 'top secret' the government then ended funding for the project, terminating it.

National space programme (1985–2010)

In 1985, the British National Space Centre (BNSC) was formed to coordinate British space activities. The BNSC was a significant contributor to the general budget of the

In 1985, the British National Space Centre (BNSC) was formed to coordinate British space activities. The BNSC was a significant contributor to the general budget of the European Space Agency

The European Space Agency (ESA) is a 23-member International organization, international organization devoted to space exploration. With its headquarters in Paris and a staff of around 2,547 people globally as of 2023, ESA was founded in 1975 ...

, and in 2005 paid 17.7% of the costs of the mandatory programmes, making it the second largest contributor. Through BNSC, the UK also took part in ESA's optional programmes such as Aurora

An aurora ( aurorae or auroras),

also commonly known as the northern lights (aurora borealis) or southern lights (aurora australis), is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly observed in high-latitude regions (around the Arc ...

, the robotic exploration initiative.

The UK decided not to contribute funds for the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a large space station that was Assembly of the International Space Station, assembled and is maintained in low Earth orbit by a collaboration of five space agencies and their contractors: NASA (United ...

, on the basis that it did not represent value for money. The British government did not take part in any crewed space endeavours during this period.

The United Kingdom continued to contribute scientific elements to satellite launches and space projects. The British probe Beagle 2, sent as part of the ESA's 2003 Mars Express

''Mars Express'' is a space exploration mission by the European Space Agency, European Space Agency (ESA) exploring the planet Mars and its moons since 2003, and the first planetary mission attempted by ESA.

''Mars Express'' consisted of two ...

mission to study the planet Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

, was lost when it failed to respond. The probe was found in 2015 by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and it has been concluded while it did land successfully, one of the solar arrays failed to deploy, blocking the communication antenna.

United Kingdom Space Agency (2010 – present)

On 1 April 2010, the

On 1 April 2010, the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

established the UK Space Agency

The United Kingdom Space Agency (UKSA) is an executive agency of the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the United Kingdom's British space programme, civil space programme. It was established on 1 April 2010 to replace the Britis ...

, an agency responsible for the British space programme. It replaced the British National Space Centre and now has responsibility for government policy and key budgets for space, as well as representing the UK in all negotiations on space matters.

As of 2015, the UK Space Agency provided 9.9% of the European Space Agency budget.

Reaction Engines Skylon

The British government partnered with the ESA in 2010 to promote a single-stage to orbitspaceplane

A spaceplane is a vehicle that can flight, fly and gliding flight, glide as an aircraft in Earth's atmosphere and function as a spacecraft in outer space. To do so, spaceplanes must incorporate features of both aircraft and spacecraft. Orbit ...

concept called Skylon. This design was developed by Reaction Engines Limited

Reaction Engines Limited (REL) was a British aerospace manufacturer founded in 1989 and based in Oxfordshire, England. The company also operated in the USA, where it used the name Reaction Engines Inc. (REI).

REL entered administration on 31 ...

, a company founded by Alan Bond after HOTOL was cancelled. The Skylon spaceplane was positively received by the British government, and the British Interplanetary Society. Successful tests of the engine pre-cooler and SABRE

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

engine design were carried out in 2012, although full funding for development of the spacecraft itself had not been confirmed. Reaction Engines filed for bankruptcy in 2024.

2011 budget boost and reforms

The British government proposed reform to the Outer Space Act 1986 in several areas, including the liabilities that cover space operations, in order to enable Britishcompanies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

' space endeavours to better compete with international competitors. There was also a proposal of a £10 million boost in capital investment, to be matched by industry.

Commercial spaceports

In July 2014, the government announced that it would build a British commercial spaceport. It planned to select a site, build the facilities, and have thespaceport

A spaceport or cosmodrome is a site for launching or receiving spacecraft, by analogy to a seaport for ships or an airport for aircraft. The word ''spaceport''—and even more so ''cosmodrome''—has traditionally referred to sites capable of ...

in operation by 2018.

Six sites were shortlisted, but the competition was ended in May 2016 with no selection made. However, in July 2018 UKSA announced that the UK government would back the development of a spaceport at A' Mhòine, in Sutherland, Scotland. Launch operations at Sutherland spaceport would be developed by Lockheed Martin

The Lockheed Martin Corporation is an American Arms industry, defense and aerospace manufacturer with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta on March 15, 1995. It is headquartered in North ...

with financial support from the UK government and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, originally with the aim of commencing operations in 2020, later delayed to 2022.

As of 2020, UKSA is supporting the development of three space launch sites in the UK. The proposed sites for spaceports, and the companies associated with them, are as follows:

* SaxaVord Spaceport – Unst, Shetland Islands

** Lockheed Martin

The Lockheed Martin Corporation is an American Arms industry, defense and aerospace manufacturer with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta on March 15, 1995. It is headquartered in North ...

/ ABL Space Systems

** Rocket Factory Augsburg

* Space Hub Sutherland – Sutherland, Scotland

** Skyrora

** Orbex

* Spaceport Cornwall – Newquay Airport, Cornwall, England

** Virgin Orbit, which ceased operations in 2023

Space Industry Act 2018

In June 2017, the government introduced a bill leading to the Space Industry Act 2018 which created a regulatory framework for the expansion of commercial space activities. This covered the development of British spaceports, for both orbital and sub-orbital activities, and launches and other activities overseas by UK entities.Commercial and private space activities

The first Briton in space, cosmonaut-researcher Helen Sharman, was funded by a private consortium without British government assistance whilst the government of theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

made up for the shortfall in the private funding. Interest in space continues in the UK's private sector, including satellite design and manufacture, developing designs for space planes and catering to the new market in space tourism

Space tourism is human space travel for recreational purposes. There are several different types of space tourism, including orbital, suborbital and lunar space tourism. Tourists are motivated by the possibility of viewing Earth from space, ...

.

Project Juno

Project Juno was a privately funded campaign, which selected Helen Sharman to be the first Briton in space. A private consortium was formed to raise money to pay the USSR for a seat on a

Project Juno was a privately funded campaign, which selected Helen Sharman to be the first Briton in space. A private consortium was formed to raise money to pay the USSR for a seat on a Soyuz

Soyuz is a transliteration of the Cyrillic text Союз (Russian language, Russian and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, 'Union'). It can refer to any union, such as a trade union (''profsoyuz'') or the Soviet Union, Union of Soviet Socialist Republi ...

mission to the Mir space station

A space station (or orbital station) is a spacecraft which remains orbital spaceflight, in orbit and human spaceflight, hosts humans for extended periods of time. It therefore is an artificial satellite featuring space habitat (facility), habitat ...

. The USSR had recently flown Toyohiro Akiyama, a Japanese journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, by a similar arrangement.

A call for applicants was publicised in the UK resulting in the selection of four astronauts: Helen Sharman, Major Timothy Mace, Clive Smith and Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Gordon Brooks. Sharman was eventually chosen for the first of what was hoped to be a number of flights with Major Timothy Mace as her backup. The cost of the flight was to be funded by various innovative schemes, including sponsoring by private British companies and a lottery system. Corporate sponsors included British Aerospace, Memorex, and Interflora, and television rights were sold to ITV.

Ultimately the Juno consortium failed to raise the entire sum and the USSR considered canceling the mission. It is believed that Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

directed the mission to proceed at Soviet cost.

Sharman was launched aboard Soyuz TM-12 on 18 May 1991, and returned aboard Soyuz TM-11 on 26 May 1991.

Surrey Satellite Technology

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) is a large spin-off company of theUniversity of Surrey

The University of Surrey is a public research university in Guildford, Surrey, England. The university received its Royal Charter, royal charter in 1966, along with a Plate glass university, number of other institutions following recommendations ...

, now fully owned by Airbus Defence & Space, that builds and operates small satellites. SSTL works with the UK Space Agency and takes on a number of tasks for the UKSA that would be done in-house by a traditional large government space agency.

Virgin Galactic

Virgin Galactic

Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. is a British-American spaceflight company founded by Richard Branson and the Virgin Group conglomerate, which retains an 11.9% stake through Virgin Investments Limited. It is headquartered in California, and opera ...

, a US company within the British-based Virgin Group owned by Sir Richard Branson

Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson (born 18 July 1950) is an English business magnate who co-founded the Virgin Group in 1970, and controlled 5 companies remaining of once more than 400.

Branson expressed his desire to become an entrepreneu ...

, is taking reservations for suborbital space flights from the general public. Its operations will use SpaceShipTwo space planes designed by Scaled Composites, which has previously developed the Ansari X-Prize winning SpaceShipOne.

Blue Origin

A private aerospace company owned byJeff Bezos

Jeffrey Preston Bezos ( ;; and Robinson (2010), p. 7. ; born January 12, 1964) is an American businessman best known as the founder, executive chairman, and former president and CEO of Amazon, the world's largest e-commerce and clou ...

has multiple plans for space. On J

4 June 2022, on its fifth flight, Blue Origin NS-21, Hamish Harding became the eighth British astronaut (reaching an apogee of 107 km) to reach space. On 4 August 2022, on its sixth flight, Blue Origin NS-22, Vanessa O'Brien became the ninth British astronaut and second female British astronaut (reaching an apogee of 107 km) to reach space, while conducting an overview study on the human brain.

British contribution to other space programmes

Communication and tracking of rockets and satellites in orbit is achieved using stations such asJodrell Bank

Jodrell Bank Observatory ( ) in Cheshire, England hosts a number of radio telescopes as part of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. The observatory was established in 1945 by Bernard Lovell, a radio astron ...

. During the Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

, Jodrell Bank

Jodrell Bank Observatory ( ) in Cheshire, England hosts a number of radio telescopes as part of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. The observatory was established in 1945 by Bernard Lovell, a radio astron ...

and other stations were used to track several satellites and probes including Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space progra ...

and Pioneer 5.

As well as providing tracking facilities for other nations, scientists from the United Kingdom have participated in other nation's space programmes, notably contributing to the development of NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

's early space programmes, and co-operation with Australian launches.

The Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, invented carbon fibre

Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (American English), carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers ( Commonwealth English), carbon-fiber-reinforced plastics, carbon-fiber reinforced-thermoplastic (CFRP, CRP, CFRTP), also known as carbon fiber, carbon comp ...

composite material. The Saunders-Roe SR.53 Rocket/jet plane in 1957 used the newly invented silver peroxide catalyst rocket engine.

The concept of the communications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a Transponder (satellite communications), transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a Rad ...

was by Arthur C. Clarke.

British astronauts

Because the British government has never developed a crewed spaceflight programme and initially did not contribute funding to the crewed space flight part of ESA's activities, the first six Britishastronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

s launched with either the American or Soviet/Russian space programmes. Despite this, on 9 October 2008, British Science and Innovation Minister Lord Drayson spoke favourably of the idea of a British astronaut. Army Air Corps test pilot Tim Peake became a member of the European Astronaut Corps in 2009, and then in 2015 the first astronaut funded by the British government when he reached the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a large space station that was Assembly of the International Space Station, assembled and is maintained in low Earth orbit by a collaboration of five space agencies and their contractors: NASA (United ...

aboard a Soyuz rocket launched from Baikonur in Kazakhstan.

To date, seven UK-born British citizens and two non-UK-born British citizen have flown in space:

Potential astronauts

US Air Force Colonel Gregory H. Johnson served as pilot on two ''Endeavour'' missions ( STS-123 andSTS-134

STS-134 (ISS assembly sequence, ISS assembly flight ULF6) was the penultimate mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program and the 25th and last spaceflight of . This flight delivered the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer and an ExPRESS Logistics Carrier ...

). Although born in the UK while his father was stationed at a US Air Force base, he has never been a British citizen and is not otherwise associated with the UK. He is sometimes incorrectly listed as a British astronaut.

Anthony Llewellyn (born in Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

, Wales) was selected as a scientist-astronaut by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

during August 1967 but resigned during September 1968, having never flown in space.

Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

Lieutenants-Colonel Anthony Boyle (born in Kidderminster) and Richard Farrimond (born in Birkenhead

Birkenhead () is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the west bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liverpool. It lies within the Historic counties of England, historic co ...

, Cheshire), MoD employee Christopher Holmes (born in London), Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

Commander Peter Longhurst (born in Staines, Middlesex) and RAF Squadron Leader Nigel Wood (born in York) were selected in February 1984 as payload specialists for the Skynet 4 programme, intended for launch using the Space Shuttle. Boyle resigned from the programme in July 1984 due to Army commitments. Prior to the cancellation of the missions after the Challenger disaster, Wood was due to fly aboard Shuttle mission STS-61-H in 1986 (with Farrimond serving as his back-up) and Longhurst was due to fly aboard Shuttle mission STS-71-C in 1987 (with Holmes serving as back-up). All resigned abruptly in 1986, citing fears and safety concerns post-Challenger.

Army Air Corps Major Timothy Mace (born in Catterick, Yorkshire) served as back-up to Helen Sharman for the Soyuz TM-12 Project Juno mission in 1991. He resigned in 1991, having not flown. Clive Smith and Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Gordon Brooks also served for a year as back-up astronauts for the Juno flight, learning Russian and preparing the scientific programme. Sharman, Mace and Brooks were subsequently put forward by the BNSC for the European Space Corps.

Former RAF pilot David Mackay was appointed as Chief Pilot by Virgin Galactic

Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. is a British-American spaceflight company founded by Richard Branson and the Virgin Group conglomerate, which retains an 11.9% stake through Virgin Investments Limited. It is headquartered in California, and opera ...

in 2009, and is participating in the flight test programme of the suborbital spaceplane SpaceShipTwo.

Singer/songwriter and actress Sarah Brightman announced on 10 October 2012 her intention to purchase a Soyuz seat to the International Space Station as a self-funded space tourist in partnership with Space Adventures. She underwent cosmonaut training with the aim of flying on Soyuz TMA-18M, but stated on 13 May 2015 that she was withdrawing "for family reasons". It is not known whether she intends to fly at a later date.

On 1 July 2021 Virgin Galactic

Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. is a British-American spaceflight company founded by Richard Branson and the Virgin Group conglomerate, which retains an 11.9% stake through Virgin Investments Limited. It is headquartered in California, and opera ...

announced that Richard Branson (its founder) and Colin Bennet (the Lead Operations Engineer) would fly as part of the crew to space on VSS Unity. Subject to the definition of space (as VSS Unity reaches above 80 km, the US government definition of space, but does not typically reach the Karman line) this would make them the UK's 8th and 9th astronauts.

The 2022 European Space Agency Astronaut Group includes three British citizens as candidates – Rosemary Coogan (career), Meganne Christian (reserve), and John McFall (parastronaut).

In fiction

Notable fictional depictions of British spacecraft or Britons in space include: * " The First Men in the Moon" by H.G.Wells ('' The Strand Magazine'' Originally Serialized December 1900 to August 1901 and published in hardcover in 1901). * " How We Went to Mars" by Sir Arthur C. Clarke ('' Amateur Science Fiction Stories'' March 1938). * ''Dan Dare

Dan Dare is a British science fiction comic hero, created by illustrator Frank Hampson who also wrote the first stories. Dare appeared in the ''Eagle'' comic series ''Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future'' from 1950 to 1967 (and subsequently in ...

, Pilot of the Future'' (comics, 1950–1967, 1980s).

* '' Journey into Space'' (radio, 1953–1955).

* '' The Quatermass Experiment'' (television, 1953).

* '' Blast Off at Woomera'' by Hugh Walters (1957).

* ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series, created by Sydney Newman, C. E. Webber and Donald Wilson (writer and producer), Donald Wilson, depicts the adventures of an extraterre ...

'' (television) – "The Ambassadors of Death

''The Ambassadors of Death'' is the third serial of the Doctor Who (season 7), seventh season of the British science fiction television series ''Doctor Who'', which was first broadcast in seven weekly parts on BBC One, BBC1 from 21 March to 2 May ...

" (1970), " The Christmas Invasion" (2005), " The Waters of Mars" (2009).

* '' The Goodies'' - " Invasion of the Moon Creatures" (television, 1973).

* '' Moonbase 3'' (television, 1973).

* '' Come Back Mrs. Noah'' (television, 1977).

* '' Moonraker'' (1979).

* '' Lifeforce'' (1985).

* '' Star Cops'' (television, 1987).

* ''Red Dwarf

A red dwarf is the smallest kind of star on the main sequence. Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of fusing star in the Milky Way, at least in the neighborhood of the Sun. However, due to their low luminosity, individual red dwarfs are ...

'' (television, 1988–1999, 2009).

* '' A Grand Day Out with Wallace and Gromit'' (short stop-motion film, 1989)

* '' Ministry of Space'' (comics, 2001–2004).

* '' Space Cadets (TV series)'' (television, 2005).

* '' Hyperdrive (TV series)'' (television, 2006–2007).

* "Capsule" Sci Fi Movie (2015).

* " Peppa Pig"— " Grampy Rabbit in Space" Cartoon (2012).

See also

* John Hodge (engineer) – British-born aerospace engineer who worked for NASA * National Space Centre – visitor centre in Leicester * United Kingdom Space Command – military space command established in 2021Notes

References

External links

UK Space Agency

*

Rocketeers.co.uk

– UK space news blog *

Virgin Galactic

UK made 'fundamental space mistake'

BBC Report on SST

BBC, 24 March 2011

article on recent UK government announcement contrasted with recent French government funding increases. ;Other resources * Hill, C.N., ''A Vertical Empire: The History of the UK Rocket and Space Programme, 1950–1971'' * Millard, Douglas,

An Overview of United Kingdom Space Activity 1957–1987

', ESA Publications. * Erik Seedhouse: ''Tim Peake and Britains's road to space.'' Springer, Cham 2017, . {{DEFAULTSORT:British Space Programme Cold War missiles of the United Kingdom Programmes of the Government of the United Kingdom Space research 1952 establishments in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...