Brian Houghton Hodgson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

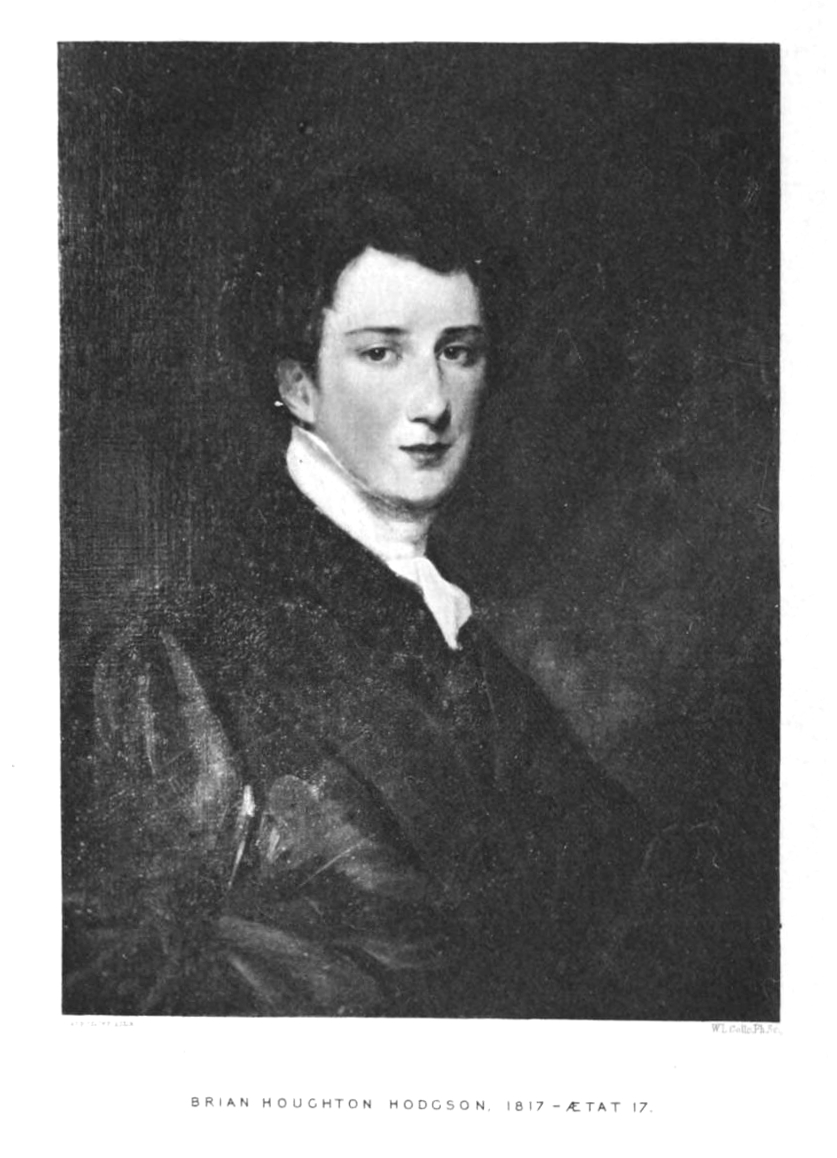

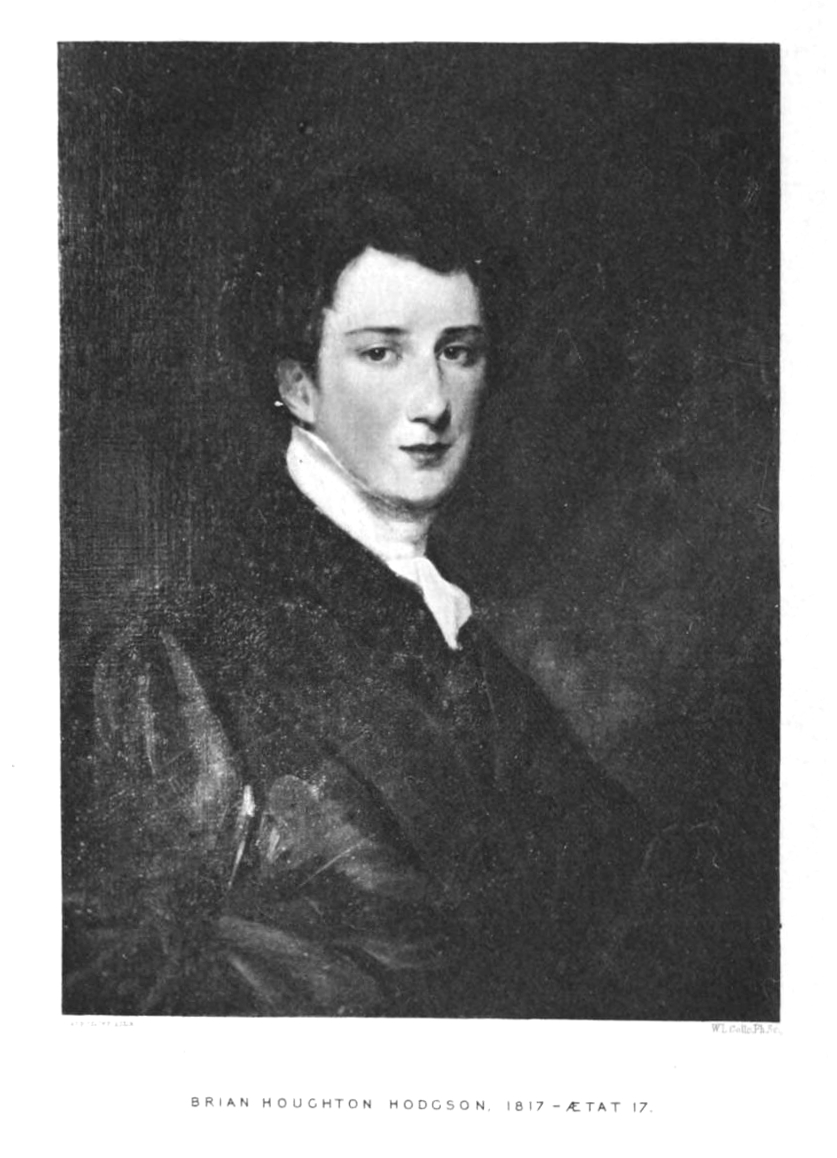

Brian Houghton Hodgson (1 February 1800 or more likely 1801 – 23 May 1894) was a pioneer naturalist and

Hodgson was the second of seven children of Brian Hodgson (1766–1858) and his wife Catherine (1776–1851), and was born at Lower Beech,

Hodgson was the second of seven children of Brian Hodgson (1766–1858) and his wife Catherine (1776–1851), and was born at Lower Beech,

Hodgson sensed the resentment of

Hodgson sensed the resentment of

Hodgson resigned in 1844 when Lord Ellenborough posted

Hodgson resigned in 1844 when Lord Ellenborough posted

Hodgson studied all aspects of natural history around him including material from Nepal, Sikkim and Bengal. He amassed a large collection of birds and mammal skins which he later donated to the

Hodgson studied all aspects of natural history around him including material from Nepal, Sikkim and Bengal. He amassed a large collection of birds and mammal skins which he later donated to the

In 1839 he wrote to his sister Fanny that he did not eat meat or drink wine and preferred Indian food habits after his ill health in 1837. During his life in India, Hodgson fathered two children (Henry, who died in Darjeeling in 1856, and Sarah, who died in Holland in 1851; a third child possibly died young) through a Kashmiri (possibly, although recorded as a "Newari") Muslim, Mehrunnisha, who lived with him from 1830 until her death around 1843. Worried about the abuse and discrimination in India of 'mixed-race' children, he had his children sent to Holland to live with his sister Fanny, but both died young. He married Ann Scott in 1853 who lived in Darjeeling until her death in January 1868. He moved to England in 1858 and lived at Dursley, Gloucestershire, and then at Alderley (1867, where his neighbours included Marianne North). In 1869 he married Susan, daughter of Rev. Chambré Townshend of Derry, who outlived him. He had no children from his marriages. He died at his home on Dover Street in London on 23 May 1894 and was buried at Alderley churchyard in Gloucestershire.

Hodgson refers to the ornithologist Samuel Tickell as his brother-in-law. Tickell's sister Mary Rosa was married to Brian's brother William Edward John Hodgson (1805 – 12 June 1838). Mary returned to England after the death of William Hodgson and married Lumisden Strange in February 1840.

In 1839 he wrote to his sister Fanny that he did not eat meat or drink wine and preferred Indian food habits after his ill health in 1837. During his life in India, Hodgson fathered two children (Henry, who died in Darjeeling in 1856, and Sarah, who died in Holland in 1851; a third child possibly died young) through a Kashmiri (possibly, although recorded as a "Newari") Muslim, Mehrunnisha, who lived with him from 1830 until her death around 1843. Worried about the abuse and discrimination in India of 'mixed-race' children, he had his children sent to Holland to live with his sister Fanny, but both died young. He married Ann Scott in 1853 who lived in Darjeeling until her death in January 1868. He moved to England in 1858 and lived at Dursley, Gloucestershire, and then at Alderley (1867, where his neighbours included Marianne North). In 1869 he married Susan, daughter of Rev. Chambré Townshend of Derry, who outlived him. He had no children from his marriages. He died at his home on Dover Street in London on 23 May 1894 and was buried at Alderley churchyard in Gloucestershire.

Hodgson refers to the ornithologist Samuel Tickell as his brother-in-law. Tickell's sister Mary Rosa was married to Brian's brother William Edward John Hodgson (1805 – 12 June 1838). Mary returned to England after the death of William Hodgson and married Lumisden Strange in February 1840.

Natural History Museum, London

Index to the Hodgson collection at the British Library

Scans of Hodgson's manuscripts on the birds of India with plates at the Zoological Society of London

* Zoological Society of Londo

An introduction to Brian Houghton HodgsonHodgson and birdsHodgson and mammalstranscriptions

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hodgson, Brian Houghton British East India Company civil servants English ornithologists Fellows of the Royal Society People from Prestbury, Cheshire 1800 births 1894 deaths Newar studies scholars British expatriates in Nepal Himalayan studies British scholars of Buddhism

ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

working in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

where he was a British Resident

Resident may refer to:

People and functions

* Resident minister, a representative of a government in a foreign country

* Resident (medicine), a stage of postgraduate medical training

* Resident (pharmacy), a stage of postgraduate pharmaceuti ...

. He described numerous species of birds and mammals from the Himalayas, and several birds were named after him by others such as Edward Blyth. He was a scholar of Newar Buddhism

Newar Buddhism is the form of Vajrayana Buddhism practiced by the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. It has developed unique socio-religious elements, which include a non-monastic Buddhist society based on the Newar caste system and ...

and wrote extensively on a range of topics relating to linguistics and religion. He was an opponent of the British proposal to introduce English as the official medium of instruction in Indian schools.

Early life

Hodgson was the second of seven children of Brian Hodgson (1766–1858) and his wife Catherine (1776–1851), and was born at Lower Beech,

Hodgson was the second of seven children of Brian Hodgson (1766–1858) and his wife Catherine (1776–1851), and was born at Lower Beech, Prestbury, Cheshire

Prestbury is a village and civil parish in Cheshire, England, about 1.5 miles (3 km) north of Macclesfield. At the 2001 census, it had a population of 3,324;Beilby Porteus

Beilby Porteus (or Porteous; 8 May 1731 – 13 May 1809), successively Bishop of Chester and of London, was a Church of England reformer and a leading abolitionist in England. He was the first Anglican in a position of authority to seriously c ...

, the Bishop of London, helped them but the financial difficulties were great. Hodgson's father worked as a warden of the Martello towers and in 1820 was barrack-master at Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

. Brian (the son) studied at Macclesfield Grammar School until 1814 and the next two years at Richmond, Surrey

Richmond is a town in south-west London,The London Government Act 1963 (c.33) (as amended) categorises the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames as an Outer London borough. Although it is on both sides of the River Thames, the Boundary Comm ...

under the tutelage of Daniel Delafosse. He was nominated for the Bengal civil service by the East India Company director James Pattison. He went to study at the East India Company College

The East India Company College, or East India College, was an educational establishment situated at Hailey, Hertfordshire, nineteen miles north of London, founded in 1806 to train "writers" (administrators) for the Honourable East India Company ( ...

and showed an aptitude for languages. An early influence was Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

who was a family friend and a staff member at the college. At the end of his first term in May 1816, he obtained a prize for Bengali. He graduated in December 1817 as a gold medallist.

India

At the age of seventeen (1818) he travelled to India as a writer in theBritish East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

. His talent for languages such as Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

and especially Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

was to prove useful for his career. He was posted as Assistant Commissioner in the Kumaon Kumaon or Kumaun may refer to:

* Kumaon division, a region in Uttarakhand, India

* Kumaon Kingdom, a former country in Uttarakhand, India

* Kumaon, Iran, a village in Isfahan Province, Iran

* , a ship of the Royal Indian Navy during WWII

See also

...

region during 1819–20 reporting to George William Traill. The Kumaon region had been annexed from Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

and in 1820 he was made assistant to the resident in Nepal, but he took up a position of acting deputy secretary in the Persian department of the Foreign office in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

. Ill health made him prefer to go back into the hills of Nepal. He took up position in 1824 as postmaster and later assistant resident in 1825. In January 1833 he became the British Resident at Kathmandu

, pushpin_map = Nepal Bagmati Province#Nepal#Asia

, coordinates =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Bagmati Prov ...

. He continued to suffer from ill health and gave up meat and alcohol in 1837. He studied the Nepalese people, producing a number of papers on their languages, literature and religion. In 1853 he made a brief visit to England and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. He married Anne Scott in the British Embassy at the Hague. She died in 1868. In 1870 he married Susan Townshend of Derry.

In 1838 he was made ''Chevalier'' of the ''Légion d'Honneur'' by the French government.

Nepal politics

Hodgson sensed the resentment of

Hodgson sensed the resentment of Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

following annexation and believed that the situation could be improved by encouraging commerce with Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

and by making use of the local manpower in the British military. He initially followed his predecessor in co-operating with Bhimsen Thapa

Bhimsen Thapa ( ne, भीमसेन थापा (August 1775 – 29 July 1839)) was a Nepalese statesman who served as the ''Mukhtiyar'' (equivalent to prime minister) and de facto ruler of Nepal from 1806 to 1837. He is widely known as the ...

, a minister, but later shifted allegiance to the young King Rajendra and sought to interact directly with the King. Hodgson later supported Bhimsen's opponents Rana Jang Pande and Krishna Ram Mishra

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is one of ...

. In July 1837 King Rajendra's infant son was found dead. Bhimsen was suspected and Hodgson recommended that he be held in custody and this led to widespread anti-British sentiment which was used by the King as well as Rana Jang Pande. Hodgson then became sympathetic to the Brahmin family of the Poudyals who were rivals of the Mishras. In 1839, Bhimsen Thapa

Bhimsen Thapa ( ne, भीमसेन थापा (August 1775 – 29 July 1839)) was a Nepalese statesman who served as the ''Mukhtiyar'' (equivalent to prime minister) and de facto ruler of Nepal from 1806 to 1837. He is widely known as the ...

committed suicide while still in custody. The nobility felt threatened by Rana Jang Pande and there was considerable instability with an army mutiny that threatened even the British Residency. Lord Auckland

Baron Auckland is a title in both the Peerage of Ireland and the Peerage of Great Britain. The first creation came in 1789 when the prominent politician and financial expert William Eden was made Baron Auckland in the Peerage of Ireland. In ...

, the Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, wanted to settle the issue but troops had already been mobilised to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and Hodgson had to negotiate through diplomacy. Hodgson was then able to set up Krishna Ram and Ranga Nath Poudyal

Ranga Nath Poudyal Atri ( ne, रङ्गनाथ पौड्याल) popularly known as Ranganath Pandit was the Mukhtiyar of Nepal from 1837 December to 1838 August and in 1840 November for about 2–3 weeks. He was the first Brahmin Prime ...

as ministers to the Nepal king. In 1842, Hodgson provided refuge to an Indian merchant Kashinath from Benares

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tra ...

who was sought by King Rajendra for recovery of some dues. When the King went to seize Kashinath, Hodgson put a hand around him and declared that the King would have to take both of them prisoner and this led to a clash. Hodgson chose not to inform the new governor-general, Lord Ellenborough

Baron Ellenborough, of Ellenborough in the County of Cumberland, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 19 April 1802 for the lawyer, judge and politician Sir Edward Law, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench from ...

, about the incident. Ellenborough's letter to Hodgson declared that no Resident would act contrary to the views of Government or extend privileges of British subjects beyond limits assigned to them. Ellenborough sought his removal from Kathmandu.

Return to England

Hodgson resigned in 1844 when Lord Ellenborough posted

Hodgson resigned in 1844 when Lord Ellenborough posted Henry Montgomery Lawrence

Brigadier-General Sir Henry Montgomery Lawrence KCB (28 June 18064 July 1857) was a British military officer, surveyor, administrator and statesman in British India. He is best known for leading a group of administrators in the Punjab affectiona ...

as Resident to Nepal and transferred Hodgson as Assistant Sub-commissioner to Simla

Shimla (; ; also known as Simla, the official name until 1972) is the capital and the largest city of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. In 1864, Shimla was declared as the summer capital of British India. After independence, th ...

. He then returned to England for a short period. During this time, Lord Ellenborough was himself dismissed. Hodgson visited his sister Fanny who had become Baroness Nahuys and was living in Holland. In 1845 he settled in Darjeeling

Darjeeling (, , ) is a town and municipality in the northernmost region of the Indian state of West Bengal. Located in the Eastern Himalayas, it has an average elevation of . To the west of Darjeeling lies the easternmost province of Nepal ...

and continued his studies of the peoples of northern India for thirteen years. Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

visited him during this period and wrote back to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

with information obtained from Hodgson on the introduced species and hybrids. Hodgson's son Henry was sent to tutor the son-in-law of Jung Bahadur Rana

Maharaja Jung Bahadur Kunwar Ranaji, (born Bir Narsingh Kunwar ( ne, वीर नरसिंह कुँवर), 18 June 1817; popularly known as Jung Bahadur Rana (JBR, ne, जङ्गबहादुर राणा)) () belonging to the ...

of Nepal. In 1857 he influenced Viscount Canning to accept Jung Bahadur Rana's help in 'suppressing' the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

. In the summer of 1858, he returned to England and would not visit India again. He lived initially at Dursley

Dursley is a market town and civil parish in southern Gloucestershire, England, almost equidistant from the cities of Bristol and Gloucester. It is under the northeast flank of Stinchcombe Hill, and about southeast of the River Severn. The t ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

but in 1867 moved to Alderley in the Cotswolds.

Ethnology and anthropology

During his posting in Nepal, Hodgson became proficient in Nepali and Newari. Hodgson was financially pressed until 1837, but he maintained a group of research assistants at his expense. He collected Buddhist texts inSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

and Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Buddh ...

and studied them with his friend Pandit Amritananda. He believed that there were four schools of Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

and wrongly assumed that the Sanskrit texts were older than those in Pali. He however became an expert on Hinayana

Hīnayāna (, ) is a Sanskrit term literally meaning the "small/deficient vehicle". Classical Chinese and Tibetan teachers translate it as "smaller vehicle". The term is applied collectively to the ''Śrāvakayāna'' and ''Pratyekabuddhayāna'' pa ...

philosophy. Hodgson had a keen interest in the culture of the people of the Himalayan regions. He believed that racial affinities could be identified on the basis of linguistics and he was influenced by the works of William Jones, Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figure ...

, Johann Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He wa ...

and Jame Prichard. From his studies he believed that the 'Aboriginal' populations of the Himalayas were not 'Aryans' or 'Caucasians', but the 'Tamulian', who he claimed were unique to India. Hodgson obtained copies of ancient Buddhist texts, the Kahgyur and the Stangyur. One copy was gifted to him by the Grand Lama. These were rare Tibetan works based on old Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

writings (brought originally from the area of the Buddha's personal teachings in Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

or Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

in India) and he was able to offer them to the Asiatic Society

The Asiatic Society is a government of India organisation founded during the Company rule in India to enhance and further the cause of "Oriental research", in this case, research into India and the surrounding regions. It was founded by the p ...

and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, commonly known as the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS), was established, according to its royal charter of 11 August 1824, to further "the investigation of subjects connected with and for the en ...

in 1838. The Russian government purchased part of the same book for £2000 around the same time.

In 1837 Hodgson collected the first Sanskrit text of the Lotus Sutra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

and sent it to translator Eugène Burnouf

Eugène Burnouf (; April 8, 1801May 28, 1852) was a French scholar, an Indologist and orientalist. His notable works include a study of Sanskrit literature, translation of the Hindu text ''Bhagavata Purana'' and Buddhist text ''Lotus Sutra''. He ...

of the Collége de France, Paris.

Educational reform

During his service in India, Hodgson was a strong proponent of education in the local languages and opposed both the use of English as a medium of instruction as advocated byLord Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

as well as the orientalist view that supported the use of Arabic, Persian or Sanskrit. From 1835 to 1839, Hodgson, William Adam, Frederick Shore and William Campbell wrote against Macaulay's idea of education in the English medium. Hodgson wrote a series of essays for the journal of the Serampore Mission ''The Friend of India'' that argued for the education in the vernacular. The essays were republished in 1880 in his ''Miscellaneous Essays Relating to Indian Subjects''.

Ornithology and natural history

Hodgson studied all aspects of natural history around him including material from Nepal, Sikkim and Bengal. He amassed a large collection of birds and mammal skins which he later donated to the

Hodgson studied all aspects of natural history around him including material from Nepal, Sikkim and Bengal. He amassed a large collection of birds and mammal skins which he later donated to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. He described a species of antelope which was named after him, the Tibetan Antelope

The Tibetan antelope or chiru (''Pantholops hodgsonii'') (, pronounced ; ) is a medium-sized bovid native to the northeastern Tibetan plateau. Most of the population live within the Chinese border, while some scatter across India and Bhutan in ...

''Pantholops hodgsonii''. He also described the pygmy hog

The pygmy hog (''Porcula salvania'') is the rarest species of pig in the world today, and is the only species in the genus ''Porcula''. It is also the smallest species of pig in the world, with its piglets being small enough to fit in one's pock ...

which he gave the scientific name of ''Porcula salvania'', the species name derived from the Sal forest ("van" in Sanskrit) habitat where it was found. He also discovered 39 species of mammals and 124 species of birds which had not been described previously, 79 of the bird species were described himself. The zoological collections presented to the British Museum by Hodgson in 1843 and 1858 contained 10,499 specimens. In addition to these, the collection also included an enormous number of drawings and coloured sketches of Indian animals by three native artists under his supervision. These sketches include anatomical details and Hodgson may have learned dissection and anatomy from Archibald Campbell Archibald Campbell may refer to:

Peerage

* Archibald Campbell of Lochawe (died before 1394), Scottish peer

* Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll (died 1513), Lord Chancellor of Scotland

* Archibald Campbell, 4th Earl of Argyll (c. 1507–1558) ...

. One of them was Raj Man Singh, but many of the paintings are unsigned. Most of them were subsequently transferred to the Zoological Society of London and the Natural History Museum.

His studies were recognised and the Royal Asiatic Society and the Linnean Society in England elected him. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1877. The Zoological Society of London sent him their diploma as a corresponding member. The Société Asiatique

The Société Asiatique (Asiatic Society) is a French learned society dedicated to the study of Asia. It was founded in 1822 with the mission of developing and diffusing knowledge of Asia. Its boundaries of geographic interest are broad, ranging ...

de Paris and the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle also honoured him. Around 1837 he planned an illustrated work on the birds and mammals of Nepal. The Museum d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris and other learned bodies came forward as supporters, three hundred and thirty subscribers registered in India, and in July 1837 he was able to write to his father that the means of publication were secured: "I make sure of three hundred and fifty to four hundred subscribers, and if we say 10 per copy of the work, this list should cover all expenses. Granted my first drawings were stiff and bad, but the new series may challenge comparison with any in existence." He hoped to finish the work in 1840.

In 1845, he presented 259 bird skins to the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham, and Newcastle upon Tyne.

After retiring to Darjeeling he took a renewed interest in natural history. During the spring of 1848 he was visited by Sir Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

. He wrote to his sister Fanny:

He wrote in 1849 on the physical geography of the Himalayan region, looking at the patterns of river-flows, the distributions and affinities of various species of mammals, birds and plants while also looking at the origins of the people inhabiting different regions.

Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829 – 31 July 1912) was a British civil servant, political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was the founder of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hum ...

said of him:

Many birds of the Himalayan region were first formerly described and given a binomial name by Hodgson. The list of world birds maintained by Frank Gill Frank Gill may refer to:

* Frank Gill (Australian footballer) (1908–1970), Australian rules footballer with Carlton

* Frank Gill (footballer, born 1948), footballer for Tranmere Rovers

*Frank Gill (politician) (1917–1982), New Zealand politicia ...

, Pamela Rasmussen

Pamela Cecile Rasmussen (born October 16, 1959) is an American ornithologist and expert on Asian birds. She was formerly a research associate at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and is based at the Michigan State University. Sh ...

and David Donsker on behalf of the International Ornithological Committee

The International Ornithologists' Union, formerly known as the International Ornithological Committee, is a group of about 200 international ornithologists, and is responsible for the International Ornithological Congress and other international ...

credits Hodgson as the authority for 29 genera and 77 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

in his ''Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication

''The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication'' is a book by Charles Darwin that was first published in January 1868.

A large proportion of the book contains detailed information on the domestication of animals and plants but it al ...

'', when discussing the origin of the domestic dog, mentions that Hodgson succeeded in taming the young of the race ''primaevus'' of the dhole

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

or Indian wild dog (''Cuon alpinus''), and in making them as fond of him and as intelligent as ordinary dogs. Darwin also cited a 1847 article by Hodgson on the varieties of sheep and goats in the Himalayas.

Personal life and death

In 1839 he wrote to his sister Fanny that he did not eat meat or drink wine and preferred Indian food habits after his ill health in 1837. During his life in India, Hodgson fathered two children (Henry, who died in Darjeeling in 1856, and Sarah, who died in Holland in 1851; a third child possibly died young) through a Kashmiri (possibly, although recorded as a "Newari") Muslim, Mehrunnisha, who lived with him from 1830 until her death around 1843. Worried about the abuse and discrimination in India of 'mixed-race' children, he had his children sent to Holland to live with his sister Fanny, but both died young. He married Ann Scott in 1853 who lived in Darjeeling until her death in January 1868. He moved to England in 1858 and lived at Dursley, Gloucestershire, and then at Alderley (1867, where his neighbours included Marianne North). In 1869 he married Susan, daughter of Rev. Chambré Townshend of Derry, who outlived him. He had no children from his marriages. He died at his home on Dover Street in London on 23 May 1894 and was buried at Alderley churchyard in Gloucestershire.

Hodgson refers to the ornithologist Samuel Tickell as his brother-in-law. Tickell's sister Mary Rosa was married to Brian's brother William Edward John Hodgson (1805 – 12 June 1838). Mary returned to England after the death of William Hodgson and married Lumisden Strange in February 1840.

In 1839 he wrote to his sister Fanny that he did not eat meat or drink wine and preferred Indian food habits after his ill health in 1837. During his life in India, Hodgson fathered two children (Henry, who died in Darjeeling in 1856, and Sarah, who died in Holland in 1851; a third child possibly died young) through a Kashmiri (possibly, although recorded as a "Newari") Muslim, Mehrunnisha, who lived with him from 1830 until her death around 1843. Worried about the abuse and discrimination in India of 'mixed-race' children, he had his children sent to Holland to live with his sister Fanny, but both died young. He married Ann Scott in 1853 who lived in Darjeeling until her death in January 1868. He moved to England in 1858 and lived at Dursley, Gloucestershire, and then at Alderley (1867, where his neighbours included Marianne North). In 1869 he married Susan, daughter of Rev. Chambré Townshend of Derry, who outlived him. He had no children from his marriages. He died at his home on Dover Street in London on 23 May 1894 and was buried at Alderley churchyard in Gloucestershire.

Hodgson refers to the ornithologist Samuel Tickell as his brother-in-law. Tickell's sister Mary Rosa was married to Brian's brother William Edward John Hodgson (1805 – 12 June 1838). Mary returned to England after the death of William Hodgson and married Lumisden Strange in February 1840.

Honours

Hodgson was awarded the DCL, ''honoris causa'' by Oxford University in 1889. His friend Joseph Hooker named the genus ''Hodgsonia

''Hodgsonia'' is a small genus of fruit-bearing vines in the family Cucurbitaceae.

''Hodgsonia'' was named for Brian Houghton Hodgson in 1853 by British botanists Joseph Dalton Hooker and Thomas Thomson, who examined the plant under Hodgson's ho ...

'' (Cucurbitaceae

The Cucurbitaceae, also called cucurbits or the gourd family, are a plant family consisting of about 965 species in around 95 genera, of which the most important to humans are:

*''Cucurbita'' – squash, pumpkin, zucchini, some gourds

*'' Lagen ...

), ''Magnolia hodgsonii

''Magnolia hodgsonii'' ( syn. ''Talauma hodgsonii''), known in Chinese as ''gai lie mu'' is a species of Magnolia native to the forests of the Himalaya and southeastern Asia, occurring in Bhutan, southwestern China, Tibet, northeastern India, nor ...

'', and a species of rhododendron, ''Rhododendron hodgsoni'', after him. Several species of bird including Hodgson's hawk-eagle, Hodgson's hawk-cuckoo

Hodgson's hawk-cuckoo (''Hierococcyx nisicolor''), also known as the whistling hawk-cuckoo is a species of cuckoo found in north-eastern India, Myanmar, southern China and southeast Asia.

Hodgson's hawk-cuckoo is a brood parasite. The chick ev ...

, Hodgson's bushchat, Hodgson's redstart, Hodgson's frogmouth

Hodgson's frogmouth (''Batrachostomus hodgsoni'') is a species of bird in the family Podargidae. It is found in Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. Its natural habitat is temperate forests.

The common name ...

and Hodgson's treecreeper

Hodgson's treecreeper (''Certhia hodgsoni'') is a small passerine bird from the southern rim of the Himalayas. Its specific distinctness from the common treecreeper (''C. familiaris'') was recently validated.

Description

This is a small bird, ...

are named after him. Other animals named after him include the Hodgson's bat, Hodgson's giant flying squirrel, Hodgson's brown-toothed shrew and Hodgson's rat snake.

He is commemorated in the scientific name of the snake species '' Gonyosoma hodgsoni'' (synonyms: ''Elaphe hodgsoni'', '' Orthriophis hodgsoni'') Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). ''The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. . ("Hodgson", p. 124).

and the plant genus ''Hodgsonia

''Hodgsonia'' is a small genus of fruit-bearing vines in the family Cucurbitaceae.

''Hodgsonia'' was named for Brian Houghton Hodgson in 1853 by British botanists Joseph Dalton Hooker and Thomas Thomson, who examined the plant under Hodgson's ho ...

'' Hook.f. & Thomson (1854) (Cucurbitaceae).

Selected publications

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *References

Sources

* *Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

*Natural History Museum, London

Index to the Hodgson collection at the British Library

Scans of Hodgson's manuscripts on the birds of India with plates at the Zoological Society of London

* Zoological Society of Londo

An introduction to Brian Houghton Hodgson

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hodgson, Brian Houghton British East India Company civil servants English ornithologists Fellows of the Royal Society People from Prestbury, Cheshire 1800 births 1894 deaths Newar studies scholars British expatriates in Nepal Himalayan studies British scholars of Buddhism