Blackfoot Confederacy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people: the ''

During the summer, the people assembled for nation gatherings. In these large assemblies, warrior societies played an important role for the men. Membership into these societies was based on brave acts and deeds.

For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley. They were located perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses, or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands would camp together. During this part of the year, buffalo also wintered in wooded areas, where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow. They were easier prey as their movements were hampered. In spring the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late

During the summer, the people assembled for nation gatherings. In these large assemblies, warrior societies played an important role for the men. Membership into these societies was based on brave acts and deeds.

For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley. They were located perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses, or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands would camp together. During this part of the year, buffalo also wintered in wooded areas, where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow. They were easier prey as their movements were hampered. In spring the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians, reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Originally, only one of the Niitsitapi tribes was called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is said to have come from the color of the peoples' moccasins, made of leather. They had typically dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One legendary story claimed that the Siksika walked through ashes of prairie fires, which in turn colored the bottoms of their moccasins black.

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians, reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Originally, only one of the Niitsitapi tribes was called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is said to have come from the color of the peoples' moccasins, made of leather. They had typically dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One legendary story claimed that the Siksika walked through ashes of prairie fires, which in turn colored the bottoms of their moccasins black.

Due to language and cultural patterns,

Due to language and cultural patterns,

The Niitsitapi main source of food on the plains was the

The Niitsitapi main source of food on the plains was the

Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.Grinnell, ''Early Blackfoot History,'' pp. 153-164 They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ''ponokamita'' (elk dogs). The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.Murdoch, ''North American Indian,'' p. 28

Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.Grinnell, ''Early Blackfoot History,'' pp. 153-164 They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ''ponokamita'' (elk dogs). The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.Murdoch, ''North American Indian,'' p. 28

Horses revolutionised life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter.

Horses revolutionised life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter.  After having driven the hostile Shoshone and

After having driven the hostile Shoshone and

Blackfoot war parties would ride hundreds of miles on raids. A boy on his first war party was given a silly or derogatory name. But after he had stolen his first horse or killed an enemy, he was given a name to honor him. Warriors would strive to perform various acts of bravery called

Blackfoot war parties would ride hundreds of miles on raids. A boy on his first war party was given a silly or derogatory name. But after he had stolen his first horse or killed an enemy, he was given a name to honor him. Warriors would strive to perform various acts of bravery called  The Niitsitapi were enemies of the

The Niitsitapi were enemies of the

In the context of shifting tribal politics due to the spread of horses and guns, the Niitsitapi initially tried to increase their trade with the HBC traders in

In the context of shifting tribal politics due to the spread of horses and guns, the Niitsitapi initially tried to increase their trade with the HBC traders in  The HBC encouraged Niitsitapiksi to trade by setting up posts on the

The HBC encouraged Niitsitapiksi to trade by setting up posts on the

Like many other Great Plains Indian nations, the Niitsitapi often had hostile relationships with white settlers. Despite the hostilities, the Blackfoot stayed largely out of the Great Plains Indian Wars, neither fighting against nor scouting for the United States army. One of their friendly bands, however, was attacked by mistake and nearly destroyed by the US Army in the

Like many other Great Plains Indian nations, the Niitsitapi often had hostile relationships with white settlers. Despite the hostilities, the Blackfoot stayed largely out of the Great Plains Indian Wars, neither fighting against nor scouting for the United States army. One of their friendly bands, however, was attacked by mistake and nearly destroyed by the US Army in the

During the mid-1800s, the Niitsitapi faced a dwindling food supply, as European-American hunters were hired by the U.S government to kill bison so the Blackfeet would remain in their reservation. Settlers were also encroaching on their territory. Without the buffalo, the Niitsitapi were forced to depend on the United States government for food supplies. In 1855, the Niitsitapi chief Lame Bull made a peace treaty with the United States government. The Lame Bull Treaty promised the Niitsitapi $20,000 annually in goods and services in exchange for their moving onto a reservation.

In 1860, very few buffalo were left, and the Niitsitapi became completely dependent on government supplies. Often the food was spoiled by the time they received it, or supplies failed to arrive at all. Hungry and desperate, Blackfoot raided white settlements for food and supplies, and outlaws on both sides stirred up trouble.

Events were catalyzed by Owl Child, a young Piegan warrior who stole a herd of horses in 1867 from an American trader named Malcolm Clarke. Clarke retaliated by tracking Owl Child down and severely beating him in full view of Owl Child's camp, and humiliating him. According to Piegan oral history, Clarke had also raped Owl Child's wife. But, Clarke was long married to Coth-co-co-na, a Piegan woman who was Owl Child's cousin. The raped woman gave birth to a child as a result of the rape, which oral history said was stillborn or killed by band elders. Two years after the beating, in 1869 Owl Child and some associates killed Clarke at his ranch after dinner, and severely wounded his son Horace. Public outcry from news of the event led to General Philip Sheridan to dispatch a band of cavalry, led by Major Eugene Baker, to find Owl Child and his camp and punish them.

During the mid-1800s, the Niitsitapi faced a dwindling food supply, as European-American hunters were hired by the U.S government to kill bison so the Blackfeet would remain in their reservation. Settlers were also encroaching on their territory. Without the buffalo, the Niitsitapi were forced to depend on the United States government for food supplies. In 1855, the Niitsitapi chief Lame Bull made a peace treaty with the United States government. The Lame Bull Treaty promised the Niitsitapi $20,000 annually in goods and services in exchange for their moving onto a reservation.

In 1860, very few buffalo were left, and the Niitsitapi became completely dependent on government supplies. Often the food was spoiled by the time they received it, or supplies failed to arrive at all. Hungry and desperate, Blackfoot raided white settlements for food and supplies, and outlaws on both sides stirred up trouble.

Events were catalyzed by Owl Child, a young Piegan warrior who stole a herd of horses in 1867 from an American trader named Malcolm Clarke. Clarke retaliated by tracking Owl Child down and severely beating him in full view of Owl Child's camp, and humiliating him. According to Piegan oral history, Clarke had also raped Owl Child's wife. But, Clarke was long married to Coth-co-co-na, a Piegan woman who was Owl Child's cousin. The raped woman gave birth to a child as a result of the rape, which oral history said was stillborn or killed by band elders. Two years after the beating, in 1869 Owl Child and some associates killed Clarke at his ranch after dinner, and severely wounded his son Horace. Public outcry from news of the event led to General Philip Sheridan to dispatch a band of cavalry, led by Major Eugene Baker, to find Owl Child and his camp and punish them.

On 23 January 1870, a camp of Piegan Indians were spotted by army scouts and reported to the dispatched cavalry, but it was mistakenly identified as a hostile band. Around 200 soldiers surrounded the camp the following morning and prepared for an ambush. Before the command to fire, the chief Heavy Runner was alerted to soldiers on the snowy bluffs above the encampment. He walked toward them, carrying his safe-conduct paper. Heavy Runner and his band of Piegans shared peace between American settlers and troops at the time of the event. Heavy Runner was shot and killed by army scout Joe Cobell, whose wife was part of the camp of the hostile Mountain Chief, further along the river, from whom he wanted to divert attention. Fellow scout Joe Kipp had realized the error and tried to signal the troops. He was threatened by the cavalry for reporting that the people they attacked were friendly.

Following the death of Heavy Runner, the soldiers attacked the camp. According to their count, they killed 173 Piegan and suffered just one U.S Army soldier casualty, who fell off his horse and broke his leg, dying of complications. Most of the victims were women, children and the elderly, as most of the younger men were out hunting. The Army took 140 Piegan prisoner and then released them. With their camp and belongings destroyed, they suffered terribly from exposure, making their way as refugees to Fort Benton.

As reports of the massacre gradually were learned in the east, members of the

On 23 January 1870, a camp of Piegan Indians were spotted by army scouts and reported to the dispatched cavalry, but it was mistakenly identified as a hostile band. Around 200 soldiers surrounded the camp the following morning and prepared for an ambush. Before the command to fire, the chief Heavy Runner was alerted to soldiers on the snowy bluffs above the encampment. He walked toward them, carrying his safe-conduct paper. Heavy Runner and his band of Piegans shared peace between American settlers and troops at the time of the event. Heavy Runner was shot and killed by army scout Joe Cobell, whose wife was part of the camp of the hostile Mountain Chief, further along the river, from whom he wanted to divert attention. Fellow scout Joe Kipp had realized the error and tried to signal the troops. He was threatened by the cavalry for reporting that the people they attacked were friendly.

Following the death of Heavy Runner, the soldiers attacked the camp. According to their count, they killed 173 Piegan and suffered just one U.S Army soldier casualty, who fell off his horse and broke his leg, dying of complications. Most of the victims were women, children and the elderly, as most of the younger men were out hunting. The Army took 140 Piegan prisoner and then released them. With their camp and belongings destroyed, they suffered terribly from exposure, making their way as refugees to Fort Benton.

As reports of the massacre gradually were learned in the east, members of the

Within the Blackfoot nation, there were different societies to which people belonged, each of which had functions for the tribe. Young people were invited into societies after proving themselves by recognized passages and rituals. For instance, young men had to perform a vision quest, begun by a spiritual cleansing in a sweat lodge. They went out from the camp alone for four days of fasting and praying. Their main goal was to see a vision that would explain their future. After having the vision, a youth returned to the village ready to join society.

In a warrior society, the men had to be prepared for battle. Again, the warriors would prepare by spiritual cleansing, then paint themselves symbolically; they often painted their horses for war as well. Leaders of the warrior society carried spears or lances called a ''coup'' stick, which was decorated with feathers, skin, and other tokens. They won prestige by "

Within the Blackfoot nation, there were different societies to which people belonged, each of which had functions for the tribe. Young people were invited into societies after proving themselves by recognized passages and rituals. For instance, young men had to perform a vision quest, begun by a spiritual cleansing in a sweat lodge. They went out from the camp alone for four days of fasting and praying. Their main goal was to see a vision that would explain their future. After having the vision, a youth returned to the village ready to join society.

In a warrior society, the men had to be prepared for battle. Again, the warriors would prepare by spiritual cleansing, then paint themselves symbolically; they often painted their horses for war as well. Leaders of the warrior society carried spears or lances called a ''coup'' stick, which was decorated with feathers, skin, and other tokens. They won prestige by " Members of the religious society protected sacred Blackfoot items and conducted religious ceremonies. They blessed the warriors before battle. Their major ceremony was the Sun Dance, or Medicine Lodge Ceremony. By engaging in the Sun Dance, their prayers would be carried up to the Creator, who would bless them with well-being and abundance of buffalo.

Women's societies also had important responsibilities for the communal tribe. They designed refined quillwork on clothing and ceremonial shields, helped prepare for battle, prepared skins and cloth to make clothing, cared for the children and taught them tribal ways, skinned and tanned the leathers used for clothing and other purposes, prepared fresh and dried foods, and performed ceremonies to help hunters in their journeys.

Members of the religious society protected sacred Blackfoot items and conducted religious ceremonies. They blessed the warriors before battle. Their major ceremony was the Sun Dance, or Medicine Lodge Ceremony. By engaging in the Sun Dance, their prayers would be carried up to the Creator, who would bless them with well-being and abundance of buffalo.

Women's societies also had important responsibilities for the communal tribe. They designed refined quillwork on clothing and ceremonial shields, helped prepare for battle, prepared skins and cloth to make clothing, cared for the children and taught them tribal ways, skinned and tanned the leathers used for clothing and other purposes, prepared fresh and dried foods, and performed ceremonies to help hunters in their journeys.

Similar to other Indigenous Peoples of the Great Plains, the Blackfoot developed a variety of different headdresses that incorporated elements of creatures important to them; these served different purposes and symbolized different associations. The typical

Similar to other Indigenous Peoples of the Great Plains, the Blackfoot developed a variety of different headdresses that incorporated elements of creatures important to them; these served different purposes and symbolized different associations. The typical

One of the most famous traditions held by the Blackfoot is their story of sun and the moon. It starts with a family of a man, wife, and two sons, who live off berries and other food they can gather, as they have no bows and arrows, or other tools (albeit a stone axe). One night, the man had a dream: he was told by the dream to get a large spider web and put it on the trail where the animals roamed, and they would get caught up and could be easily killed with the stone axe he had. The man had done so and saw that it was true. One day, he came home from bringing in some fresh meat from the trail and discovered his wife to be applying perfume on herself. He thought that she must have another lover since she never did this before. He then told his wife that he was going to move a web and asked if she could bring in the meat and wood he had left outside from a previous hunt. She had reluctantly gone out and passed over a hill. The wife looked back three times and saw her husband in the same place she had left him, so she continued on to retrieve the meat. The father then asked his children if they went with their mother to find wood, but they never had. However they knew the location in which she retrieved it from.

The man set out and found the timber along with a den of rattlesnakes, one of which was his wife's lover. He set the timber on fire and killed the snakes. He knew by doing this that his wife would become enraged, so the man returned home. He told the children to flee and gave them a stick, stone, and moss to use if their mother chased after them. He remained at the house and put a web over his front door. The wife tried to get in but became stuck and had her leg cut off. She then put her head through and he cut that off also. While the body followed the husband to the creek, the head followed the children. The oldest boy saw the head behind them and threw the stick. The stick turned into a great forest. The head made it through, so the younger brother instructed the elder to throw the stone. He did so, and where the stone landed a huge mountain popped up. It spanned from big water (ocean) to big water and the head was forced to go through it, not around. The head met a group of rams and said to them she would marry their chief if they butted their way through the mountain. The chief agreed and they butted until their horns were worn down, but this still was not through. She then asked the ants if they could burrow through the mountain with the same stipulations, it was agreed and they get her the rest of the way through. The children were far ahead, but eventually saw the head rolling behind them. The boys wet the moss and wrung it out behind themselves. They were then in a different land surrounded by an expanse of water (the 'new land' is commonly interpreted as

One of the most famous traditions held by the Blackfoot is their story of sun and the moon. It starts with a family of a man, wife, and two sons, who live off berries and other food they can gather, as they have no bows and arrows, or other tools (albeit a stone axe). One night, the man had a dream: he was told by the dream to get a large spider web and put it on the trail where the animals roamed, and they would get caught up and could be easily killed with the stone axe he had. The man had done so and saw that it was true. One day, he came home from bringing in some fresh meat from the trail and discovered his wife to be applying perfume on herself. He thought that she must have another lover since she never did this before. He then told his wife that he was going to move a web and asked if she could bring in the meat and wood he had left outside from a previous hunt. She had reluctantly gone out and passed over a hill. The wife looked back three times and saw her husband in the same place she had left him, so she continued on to retrieve the meat. The father then asked his children if they went with their mother to find wood, but they never had. However they knew the location in which she retrieved it from.

The man set out and found the timber along with a den of rattlesnakes, one of which was his wife's lover. He set the timber on fire and killed the snakes. He knew by doing this that his wife would become enraged, so the man returned home. He told the children to flee and gave them a stick, stone, and moss to use if their mother chased after them. He remained at the house and put a web over his front door. The wife tried to get in but became stuck and had her leg cut off. She then put her head through and he cut that off also. While the body followed the husband to the creek, the head followed the children. The oldest boy saw the head behind them and threw the stick. The stick turned into a great forest. The head made it through, so the younger brother instructed the elder to throw the stone. He did so, and where the stone landed a huge mountain popped up. It spanned from big water (ocean) to big water and the head was forced to go through it, not around. The head met a group of rams and said to them she would marry their chief if they butted their way through the mountain. The chief agreed and they butted until their horns were worn down, but this still was not through. She then asked the ants if they could burrow through the mountain with the same stipulations, it was agreed and they get her the rest of the way through. The children were far ahead, but eventually saw the head rolling behind them. The boys wet the moss and wrung it out behind themselves. They were then in a different land surrounded by an expanse of water (the 'new land' is commonly interpreted as

Today, many of the Blackfoot live on reserves in Canada. About 8,500 live on the Montana reservation of . In 1896, the Blackfoot sold a large portion of their land to the United States government, which hoped to find gold or copper deposits. No such mineral deposits were found. In 1910, the land was set aside as Glacier National Park. Some Blackfoot work there and occasional Native American ceremonies are held there.

Unemployment is a challenging problem on the Blackfeet Reservation and on Canadian Blackfoot reserves, because of their isolation from major urban areas. Many people work as farmers, but there are not enough other jobs nearby. To find work, many Blackfoot have relocated from the reservation to towns and cities. Some companies pay the Blackfoot governments to lease use of lands for extracting oil, natural gas, and other resources. The nations have operated such businesses such as the Blackfoot Writing Company, a pen and pencil factory, which opened in 1972, but it closed in the late 1990s. In Canada, the Northern Piegan make traditional craft clothing and moccasins, and the Kainai operate a shopping center and factory.

In 1974, the Blackfoot Community College, a

Today, many of the Blackfoot live on reserves in Canada. About 8,500 live on the Montana reservation of . In 1896, the Blackfoot sold a large portion of their land to the United States government, which hoped to find gold or copper deposits. No such mineral deposits were found. In 1910, the land was set aside as Glacier National Park. Some Blackfoot work there and occasional Native American ceremonies are held there.

Unemployment is a challenging problem on the Blackfeet Reservation and on Canadian Blackfoot reserves, because of their isolation from major urban areas. Many people work as farmers, but there are not enough other jobs nearby. To find work, many Blackfoot have relocated from the reservation to towns and cities. Some companies pay the Blackfoot governments to lease use of lands for extracting oil, natural gas, and other resources. The nations have operated such businesses such as the Blackfoot Writing Company, a pen and pencil factory, which opened in 1972, but it closed in the late 1990s. In Canada, the Northern Piegan make traditional craft clothing and moccasins, and the Kainai operate a shopping center and factory.

In 1974, the Blackfoot Community College, a

The Blackfoot continue many cultural traditions of the past and hope to extend their ancestors' traditions to their children. They want to teach their children the Pikuni language as well as other traditional knowledge. In the early 20th century, a white woman named

The Blackfoot continue many cultural traditions of the past and hope to extend their ancestors' traditions to their children. They want to teach their children the Pikuni language as well as other traditional knowledge. In the early 20th century, a white woman named

*

*

"Blackfeet Actress Misty Upham On Filming 'Jimmy P.' with Benicio Del Toro"

, ''

Blackfoot homepage

Photographs of the Blackfoot, their homelands, material culture, and ceremonies from the collection of th

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Blackfoot Digital Library

project of Red Crow Community College and the University of Lethbridge

Blackfoot Anthropological Notes

at Dartmouth College Library * {{DEFAULTSORT:Blackfoot Confederacy Algonquian peoples Plains tribes First Nations history Native American history of Montana First Nations in Alberta Native American tribes in Montana Native American tribes in Wyoming

Siksika

The Siksika Nation ( bla, Siksiká) is a First Nations in Canada, First Nation in southern Alberta, Canada. The name ''Siksiká'' comes from the Blackfoot language, Blackfoot words ''sik'' (black) and ''iká'' (foot), with a connector ''s'' bet ...

'' ("Blackfoot"), the '' Kainai or Blood'' ("Many Chiefs"), and two sections of the Peigan or Piikani ("Splotchy Robe") – the Northern Piikani (''Aapátohsipikáni'') and the Southern Piikani (''Amskapi Piikani'' or ''Pikuni''). Broader definitions include groups such as the ''Tsúùtínà'' ( Sarcee) and ''A'aninin'' (Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

) who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Historically, the member peoples of the Confederacy were nomadic bison hunters

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North Amer ...

and trout fishermen, who ranged across large areas of the northern Great Plains of western North America, specifically the semi-arid

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi- ...

shortgrass prairie

The shortgrass prairie is an ecosystem located in the Great Plains of North America. The two most dominant grasses in the shortgrass prairie are blue grama (''Bouteloua gracilis'') and buffalograss ('' Bouteloua dactyloides''), the two less domi ...

ecological region. They followed the bison herds as they migrated between what are now the United States and Canada, as far north as the Bow River

The Bow River is a river in Alberta, Canada. It begins within the Canadian Rocky Mountains and winds through the Alberta foothills onto the prairies, where it meets the Oldman River, the two then forming the South Saskatchewan River. These w ...

. In the first half of the 18th century, they acquired horses and firearms from white traders and their Cree and Assiniboine go-betweens. The Blackfoot used these to expand their territory at the expense of neighboring tribes.

Today, three Blackfoot First Nation

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

band governments (the Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani Nations) reside in the Canadian province of Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, while the Blackfeet Nation is a federally recognized Native American tribe

In the United States, an American Indian tribe, Native American tribe, Alaska Native village, tribal nation, or similar concept is any extant or historical clan, tribe, band, nation, or other group or community of Native Americans in the Unit ...

of Southern Piikani in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, United States. Additionally, the Gros Ventre are members of the federally recognized Fort Belknap Indian Community of the Fort Belknap Reservation of Montana

The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation ( ats, ’ak3ɔ́ɔyɔ́ɔ, lit=the fence or ats, ’ɔ’ɔ́ɔ́ɔ́nííítaan’ɔ, lit=Gros Ventre tribe, label=none) is shared by two Native American tribes, the A'aninin ( Gros Ventre) and the Nakoda ...

in the United States and the Tsuutʼina Nation is a First Nation band government in Alberta, Canada.

Government

The four Blackfoot nations come together to make up what is known as the Blackfoot Confederacy, meaning that they have banded together to help one another. The nations have their own separate governments ruled by a head chief, but regularly come together for religious and social celebrations. Originally the Blackfoot/Plains Confederacy consisted of three peoples ("nation", "tribes", "tribal nations") based on kinship anddialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a ...

, but all speaking the common language of Blackfoot, one of the Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( or ; also Algonkian) are a subfamily of indigenous American languages that include most languages in the Algic language family. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from the orthographically simi ...

family. The three were the ''Piikáni'' (historically called "Piegan Blackfeet" in English-language sources), the ''Káínaa'' (called "Bloods"), and the ''Siksikáwa'' ("Blackfoot"). They later allied with the unrelated ''Tsuu T'ina'' ("Sarcee"), who became merged into the Confederacy and, (for a time) with the ''Atsina,'' or A'aninin (''Gros Ventre'').

Each of these highly decentralized peoples were divided into many bands, which ranged in size from 10 to 30 lodges, or about 80 to 240 persons. The band was the basic unit of organization for hunting and defence.

The Confederacy occupied a large territory where they hunted and foraged; in the 19th century it was divided by the current Canada–US international border. But during the late nineteenth century, both governments forced the peoples to end their nomadic traditions and settle on "Indian reserves

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Ind ...

" (Canadian terminology) or "Indian reservations

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

" (US terminology). The South Peigan are the only group who chose to settle in Montana. The other three Blackfoot-speaking peoples and the Sarcee are located in Alberta. Together, the Blackfoot-speakers call themselves the ''Niitsítapi'' (the "Original People"). After leaving the Confederacy, the Gros Ventres also settled on a reservation in Montana.

When these peoples were forced to end their nomadic traditions, their social structures changed. Tribal nations, which had formerly been mostly ethnic associations, were institutionalized as governments (referred to as "tribes" in the United States and "bands" or "First Nations" in Canada). The Piegan were divided into the North Peigan in Alberta, and the South Peigan in Montana.

History

The Confederacy had a territory that stretched from theNorth Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

(called ''Ponoká'sisaahta'') along what is now Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city ancho ...

, Alberta, in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, to the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains a ...

(called ''Otahkoiitahtayi'') of Montana in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, and from the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

(called ''Miistakistsi'') and along the South Saskatchewan River

The South Saskatchewan River is a major river in Canada that flows through the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

For the first half of the 20th century, the South Saskatchewan would completely freeze over during winter, creating spectacular ...

to the present Alberta-Saskatchewan border (called ''Kaayihkimikoyi''), east past the Cypress Hills. They called their tribal territory ''Niitsitpiis-stahkoii'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᐨᑯᐧ ᓴᐦᖾᐟ)- "Original People

s Land." To the east, the Innu and Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical country St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our nclusiveland'), which is located in northern Quebec and Labrador, neighb ...

called their territory ''Nitassinan

Nitassinan ( moe, script=Cans, i=no, ᓂᑕᔅᓯᓇᓐ) is the ancestral homeland of the Innu, an indigenous people of Eastern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. Nitassinan means "our land" in the Innu language. The territory covers the eastern por ...

'' – "Our Land." They had adopted the use of the horse from other Plains tribes, probably by the early eighteenth century, which gave them expanded range and mobility, as well as advantages in hunting.

The basic social unit

The term "level of analysis" is used in the social sciences to point to the location, size, or scale of a research target.

"Level of analysis" is distinct from the term " unit of observation" in that the former refers to a more or less integrated ...

of the ''Niitsitapi'' above the family was the band, varying from about 10 to 30 lodges, about 80 to 241 people. This size group was large enough to defend against attack and to undertake communal hunts, but was also small enough for flexibility. Each band consisted of a respected leader , possibly his brothers and parents, and others who were not related. Since the band was defined by place of residence, rather than by kinship, a person was free to leave one band and join another, which tended to ameliorate leadership disputes. As well, should a band fall upon hard times, its members could split up and join other bands. In practice, bands were constantly forming and breaking up. The system maximized flexibility and was an ideal organization for a hunting people on the northwestern Great Plains.

During the summer, the people assembled for nation gatherings. In these large assemblies, warrior societies played an important role for the men. Membership into these societies was based on brave acts and deeds.

For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley. They were located perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses, or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands would camp together. During this part of the year, buffalo also wintered in wooded areas, where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow. They were easier prey as their movements were hampered. In spring the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late

During the summer, the people assembled for nation gatherings. In these large assemblies, warrior societies played an important role for the men. Membership into these societies was based on brave acts and deeds.

For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in their winter camps along a wooded river valley. They were located perhaps a day's march apart, not moving camp unless food for the people and horses, or firewood became depleted. Where there was adequate wood and game resources, some bands would camp together. During this part of the year, buffalo also wintered in wooded areas, where they were partially sheltered from storms and snow. They were easier prey as their movements were hampered. In spring the buffalo moved out onto the grasslands to forage on new spring growth. The Blackfoot did not follow immediately, for fear of late blizzard

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling ...

s. As dried food or game became depleted, the bands would split up and begin to hunt the buffalo.

In midsummer, when the chokecherries

''Prunus virginiana'', commonly called bitter-berry, chokecherry, Virginia bird cherry, and western chokecherry (also black chokecherry for ''P. virginiana'' var. ''demissa''), is a species of bird cherry (''Prunus'' subgenus ''Padus'') nat ...

ripened, the people regrouped for their major ceremony, the ''Okan'' (Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individua ...

). This was the only time of year when the four nations would assemble. The gathering reinforced the bonds among the various groups and linked individuals with the nations. Communal buffalo hunts provided food for the people, as well as offerings of the bulls' tongues (a delicacy) for the ceremonies. These ceremonies are sacred to the people. After the ''Okan'', the people again separated to follow the buffalo. They used the buffalo hides to make their dwellings and temporary tipis.

In the fall, the people would gradually shift to their wintering areas. The men would prepare the buffalo jumps and pounds for capturing or driving the bison for hunting. Several groups of people might join together at particularly good sites, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is a buffalo jump located where the foothills of the Rocky Mountains begin to rise from the prairie 18 km (11.2 mi) west of Fort Macleod, Alberta, Canada on highway 785. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site an ...

. As the buffalo were naturally driven into the area by the gradual late summer drying off of the open grasslands, the Blackfoot would carry out great communal buffalo kills.

The women processed the buffalo, preparing dried meat, and combining it for nutrition and flavor with dried fruits into pemmican

Pemmican (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigenou ...

, to last them through winter and other times when hunting was poor. At the end of the fall, the Blackfoot would move to their winter camps. The women worked the buffalo and other game skins for clothing, as well as to reinforce their dwellings; other elements were used to make warm fur robes, leggings, cords and other needed items. Animal sinews were used to tie arrow points and lances to throwing sticks, or for bridles for horses.

The Niitsitapi maintained this traditional way of life based on hunting bison, until the near extirpation

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

of the bison by 1881 forced them to adapt their ways of life in response to the encroachment of the European settlers and their descendants. In the United States, they were restricted to land assigned in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was signed on September 17, 1851 between United States treaty commissioners and representatives of the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations. Also known as Horse Cre ...

. Nearly three decades later, they were given a distinct reservation in the Sweetgrass Hills Treaty of 1887. In 1877, the Canadian Niitsitapi signed Treaty 7

Treaty 7 is an agreement between the Crown and several, mainly Blackfoot, First Nation band governments in what is today the southern portion of Alberta. The idea of developing treaties for Blackfoot lands was brought to Blackfoot chief Cro ...

and settled on reserves in southern Alberta.

This began a period of great struggle and economic hardship; the Niitsitapi had to try to adapt to a completely new way of life. They suffered a high rate of fatalities when exposed to Eurasian diseases, for which they had no natural immunity.

Eventually, they established a viable economy based on farming, ranching, and light industry. Their population has increased to about 16,000 in Canada and 15,000 in the U.S. today. With their new economic stability, the Niitsitapi have been free to adapt their culture and traditions to their new circumstances, renewing their connection to their ancient roots.

Early history

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians, reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Originally, only one of the Niitsitapi tribes was called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is said to have come from the color of the peoples' moccasins, made of leather. They had typically dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One legendary story claimed that the Siksika walked through ashes of prairie fires, which in turn colored the bottoms of their moccasins black.

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians, reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Originally, only one of the Niitsitapi tribes was called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is said to have come from the color of the peoples' moccasins, made of leather. They had typically dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One legendary story claimed that the Siksika walked through ashes of prairie fires, which in turn colored the bottoms of their moccasins black.

Due to language and cultural patterns,

Due to language and cultural patterns, anthropologists

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

believe the Niitsitapi did not originate in the Great Plains of the Midwest North America, but migrated from the upper Northeastern part of the country. They coalesced as a group while living in the forests of what is now the Northeastern United States. They were mostly located around the modern-day border between Canada and the state of Maine. By 1200, the Niitsitapi were moving in search of more land. They moved west and settled for a while north of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

in present-day Canada, but had to compete for resources with existing tribes. They left the Great Lakes area and kept moving west.

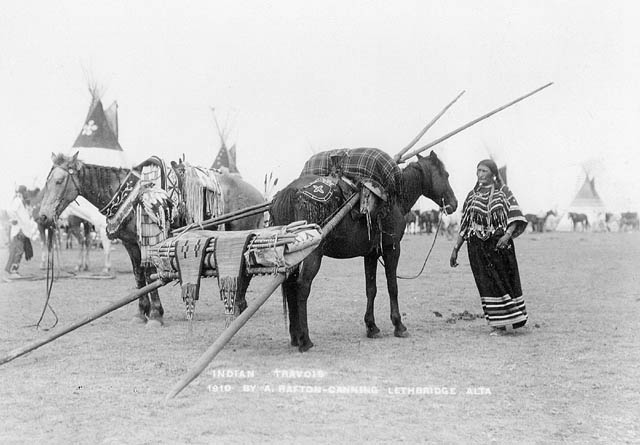

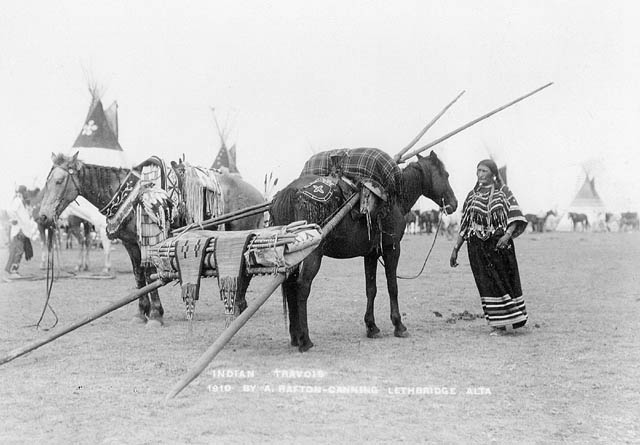

When they moved, they usually packed their belongings on an A-shaped sled called a ''travois

A travois (; Canadian French, from French , a frame for restraining horses; also obsolete travoy or travoise) is a historical frame structure that was used by indigenous peoples, notably the Plains Aboriginals of North America, to drag loads ove ...

.'' The travois was designed for transport over dry land. The Blackfoot had relied on dogs to pull the ''travois''; they did not acquire horses until the 18th century. From the Great Lakes area, they continued to move west and eventually settled in the Great Plains.

The Plains had covered approximately with the Saskatchewan River

The Saskatchewan River (Cree: ''kisiskāciwani-sīpiy'', "swift flowing river") is a major river in Canada. It stretches about from where it is formed by the joining together of the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers to Lake Winn ...

to the north, the Rio Grande to the south, the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

to the east, and the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

to the west.Taylor, 9. Adopting the use of the horse, the Niitsitapi established themselves as one of the most powerful Indian tribes on the Plains in the late 18th century, earning themselves the name "The Lords of the Plains." Niitsitapi stories trace their residence and possession of their plains territory to "time immemorial."

Importance and uses of bison

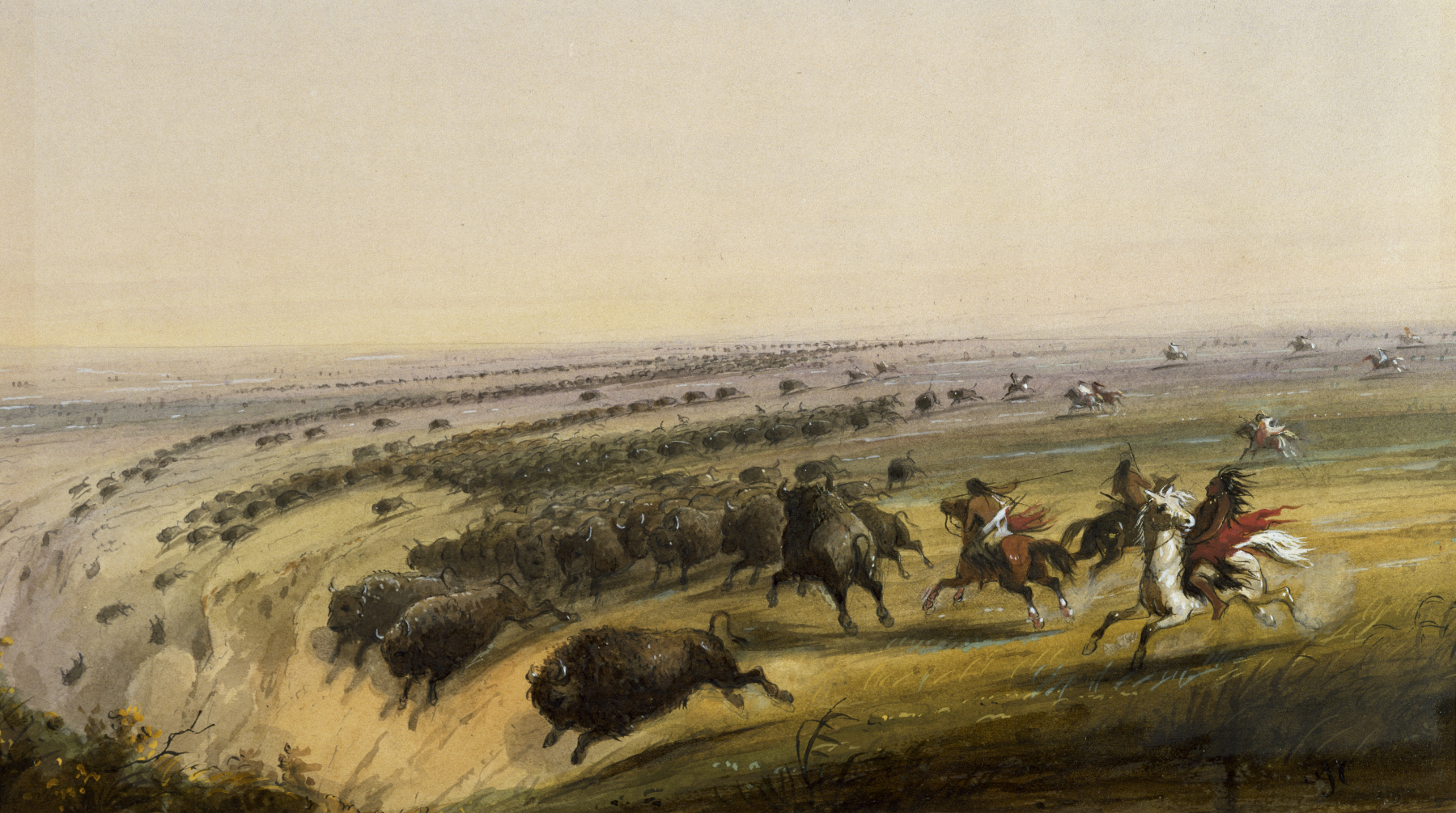

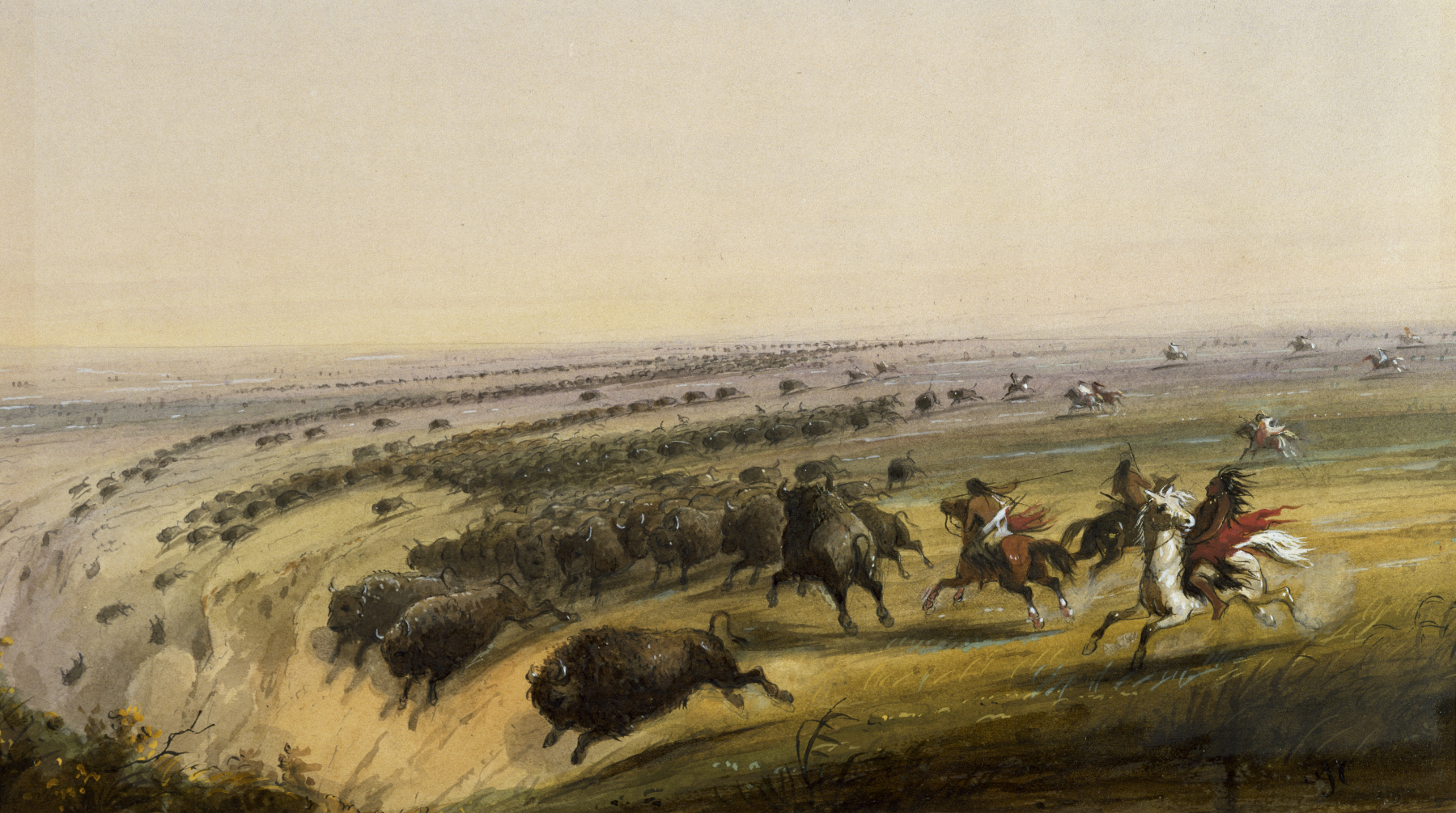

The Niitsitapi main source of food on the plains was the

The Niitsitapi main source of food on the plains was the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply Bubalina, buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongs ...

(buffalo), the largest mammal in North America, standing about tall and weighing up to .David Murdoch, "North American Indian", eds. Marion Dent and others, Vol. ''Eyewitness Books''(Dorling Kindersley Limited, London: Alfred A.Knopf, Inc., 1937), 28-29. Before the introduction of horses, the Niitsitapi needed other ways to get in range. The buffalo jump

A buffalo jump, or sometimes bison jump, is a cliff formation which Indigenous peoples of North America historically used to hunt and kill plains bison in mass quantities. The broader term game jump refers to a man-made jump or cliff used for hu ...

was one of the most common ways. The hunters would round up the buffalo into V-shaped pens, and drive them over a cliff (they hunted pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American a ...

antelopes in the same way). Afterwards the hunters would go to the bottom and take as much meat as they could carry back to camp. They also used camouflage for hunting. The hunters would take buffalo skins from previous hunting trips and drape them over their bodies to blend in and mask their scent. By subtle moves, the hunters could get close to the herd. When close enough, the hunters would attack with arrows or spears to kill wounded animals.

The people used virtually all parts of the body and skin. The women prepared the meat for food: by boiling, roasting or drying for jerky

Jerky is lean trimmed meat cut into strips and dried (dehydrated) to prevent spoilage. Normally, this drying includes the addition of salt to prevent bacteria growth before the meat has finished the dehydrating process. The word "jerky" derive ...

. This processed it to last a long time without spoiling, and they depended on bison meat to get through the winters. The winters were long, harsh, and cold due to the lack of trees in the Plains, so people stockpiled meat in summer. As a ritual, hunters often ate the bison heart minutes after the kill. The women tanned and prepared the skins to cover the tepees. These were made of log poles, with the skins draped over it. The tepee remained warm in the winter and cool in the summer, and was a great shield against the wind.

The women also made clothing from the skins, such as robes and moccasins, and made soap from the fat. Both men and women made utensils, sewing needles and tools from the bones, using tendon for fastening and binding. The stomach and bladder were cleaned and prepared for use for storing liquids. Dried bison dung was fuel for the fires. The Niitsitapi considered the animal sacred and integral to their lives.

Discovery and uses of horses

Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.Grinnell, ''Early Blackfoot History,'' pp. 153-164 They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ''ponokamita'' (elk dogs). The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.Murdoch, ''North American Indian,'' p. 28

Up until around 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry and pull some of their goods. They had not seen horses in their previous lands, but were introduced to them on the Plains, as other tribes, such as the Shoshone, had already adopted their use.Grinnell, ''Early Blackfoot History,'' pp. 153-164 They saw the advantages of horses and wanted some. The Blackfoot called the horses ''ponokamita'' (elk dogs). The horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved at a greater speed. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.Murdoch, ''North American Indian,'' p. 28

Horses revolutionised life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter.

Horses revolutionised life on the Great Plains and soon came to be regarded as a measure of wealth. Warriors regularly raided other tribes for their best horses. Horses were generally used as universal standards of barter. Medicine men

A medicine man is a traditional healer and spiritual leader among the indigenous people of the Americas.

Medicine Man or The Medicine Man may also refer to:

Films

* ''The Medicine Man'' (1917 film), an American silent film directed by Clifford S ...

were paid for cures and healing with horses. Those who designed shields or war bonnets were also paid in horses. The men gave horses to those who were owed gifts as well as to the needy. An individual's wealth rose with the number of horses accumulated, but a man did not keep an abundance of them. The individual's prestige and status was judged by the number of horses that he could give away. For the Indians who lived on the Plains, the principal value of property was to share it with others.

After having driven the hostile Shoshone and

After having driven the hostile Shoshone and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

from the Northwestern Plains, the Niitsitapi began in 1800 a long phase of keen competition in the fur trade with their former Cree allies, which often escalated militarily. In addition both groups had adapted to using horses about 1730, so by mid-century an adequate supply of horses became a question of survival. Horse theft was at this stage not only a proof of courage, but often a desperate contribution to survival, for many ethnic groups competed for hunting in the grasslands.

The Cree and Assiniboine continued horse raiding against the Gros Ventre (in Cree: ''Pawistiko Iyiniwak'' – "Rapids People" – "People of the Rapids"), allies of the Niitsitapi. The Gros Ventres were also known as ''Niya Wati Inew'', ''Naywattamee'' ("They Live in Holes People"), because their tribal lands were along the Saskatchewan River Forks

Saskatchewan River Forks refers to the area in Canada where the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan rivers merge to create the Saskatchewan River. It is about east of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. The province of Saskatchewan maintains the ...

(the confluence of North and South Saskatchewan River). They had to withstand attacks of enemies with guns. In retaliation for Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

(HBC) supplying their enemies with weapons, the Gros Ventre attacked and burned in 1793 South Branch House

South Branch House (1785-1794, 1805-1870) was the only significant fur trading post on the South Saskatchewan River. Most trade was on the North Saskatchewan River which was closer to the wooded beaver country. West of the Saskatchewan River Forks ...

of the HBC on the South Saskatchewan River near the present village of St. Louis, Saskatchewan. Then, the tribe moved southward to the Milk River in Montana and allied themselves with the Blackfoot. The area between the North Saskatchewan River and Battle River (the name derives from the war fought between these two tribal groups) was the limit of the now warring tribal alliances.

Enemies and warrior culture

Blackfoot war parties would ride hundreds of miles on raids. A boy on his first war party was given a silly or derogatory name. But after he had stolen his first horse or killed an enemy, he was given a name to honor him. Warriors would strive to perform various acts of bravery called

Blackfoot war parties would ride hundreds of miles on raids. A boy on his first war party was given a silly or derogatory name. But after he had stolen his first horse or killed an enemy, he was given a name to honor him. Warriors would strive to perform various acts of bravery called counting coup

Among the Plains Indians of North America, counting coup is the warrior tradition of winning prestige against an enemy in battle. It is one of the traditional ways of showing bravery in the face of an enemy and involves intimidating him, and, it ...

, in order to move up in social rank. The coups in order of importance were: taking a gun from a living enemy and or touching him directly; capturing lances, and bows; scalping an enemy; killing an enemy; freeing a tied horse from in front of an enemy lodge; leading a war party; scouting for a war party; stealing headdresses, shields, pipes (sacred ceremonial pipes); and driving a herd of stolen horses back to camp.

The Niitsitapi were enemies of the

The Niitsitapi were enemies of the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

, Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

(''kiihtsipimiitapi'' – ″Pinto People″), and Sioux (Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota) (called ''pinaapisinaa'' – "East Cree") on the Great Plains; and the Shoshone, Flathead, Kalispel

The Pend d'Oreille ( ), also known as the Kalispel (), are Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau. Today many of them live in Montana and eastern Washington of the United States. The Kalispel peoples referred to their primary tribal range a ...

, Kootenai

The Kutenai ( ), also known as the Ktunaxa ( ; ), Ksanka ( ), Kootenay (in Canada) and Kootenai (in the United States), are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern ...

(called ''kotonáá'wa'') and Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

(called ''komonóítapiikoan'') in the mountain country to their west and southwest. Their most mighty and most dangerous enemy, however, were the political/military/trading alliance of the Iron Confederacy

The Iron Confederacy or Iron Confederation (also known as Cree-Assiniboine in English or cr, script=Latn, Nehiyaw-Pwat, label=none in Cree) was a political and military alliance of Plains Indians of what is now Western Canada and the northern Un ...

or ''Nehiyaw-Pwat'' (in Plains Cree: ''Nehiyaw'' – 'Cree' and ''Pwat'' or ''Pwat-sak'' – 'Sioux, i.e. Assiniboine') – named after the dominating Plains Cree (called ''Asinaa'') and Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

(called ''Niitsísinaa'' – "Original Cree"). These included the Stoney (called ''Saahsáísso'kitaki'' or ''Sahsi-sokitaki'' – ″Sarcee trying to cut″), Saulteaux

The Saulteaux (pronounced , or in imitation of the French pronunciation , also written Salteaux, Saulteau and other variants), otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations band government in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, A ...

(or Plains Ojibwe), and Métis to the north, east and southeast.

With the expansion of the ''Nehiyaw-Pwat'' to the north, west and southwest, they integrated larger groups of Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified ...

, Danezaa (''Dunneza'' – 'The real (prototypical) people'), Ktunaxa, Flathead, and later Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

(called ''atsíína'' – "Gut People" or "like a Cree"), in their local groups. Loosely allied with the ''Nehiyaw-Pwat'', but politically independent, were neighboring tribes like the Ktunaxa

The Kutenai ( ), also known as the Ktunaxa ( ; ), Ksanka ( ), Kootenay (in Canada) and Kootenai (in the United States), are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern ...

, Secwepemc and in particular the arch enemy of the Blackfoot, the Crow, or Indian trading partners like the Nez Perce and Flathead.

The Shoshone acquired horses much sooner than the Blackfoot and soon occupied much of present-day Alberta, most of Montana, and parts of Wyoming, and raided the Blackfoot frequently. Once the Piegan gained access to horses of their own and guns, obtained from the HBC via the Cree and Assiniboine, the situation changed. By 1787 David Thompson reports that the Blackfoot had completely conquered most of Shoshone territory, and frequently captured Shoshone women and children and forcibly assimilated them into Blackfoot society, further increasing their advantages over the Shoshone. Thompson reports that Blackfoot territory in 1787 was from the North Saskatchewan River in the north to the Missouri River in the South, and from Rocky Mountains in the west out to a distance of to the east.

Between 1790 and 1850, the ''Nehiyaw-Pwat'' were at the height of their power; they could successfully defend their territories against the Sioux (Lakota, Nakota and Dakota) and the Niitsitapi Confederacy. During the so-called Buffalo Wars (about 1850 – 1870), they penetrated further and further into the territory from the Niitsitapi Confederacy in search for the buffalo, so that the Piegan were forced to give way in the region of the Missouri River (in Cree: ''Pikano Sipi'' – "Muddy River", "Muddy, turbid River"), the Kainai withdrew to the Bow River

The Bow River is a river in Alberta, Canada. It begins within the Canadian Rocky Mountains and winds through the Alberta foothills onto the prairies, where it meets the Oldman River, the two then forming the South Saskatchewan River. These w ...

and Belly River

Belly River is a river in northwest Montana, United States and southern Alberta, Canada. It is a tributary of the Oldman River, itself a tributary of the South Saskatchewan River.

The name of the river may come from the Blackfoot word of , mean ...

; only the Siksika could hold their tribal lands along the Red Deer River

The Red Deer River is a river in Alberta and a small portion of Saskatchewan, Canada. It is a major tributary of the South Saskatchewan River and is part of the larger Saskatchewan-Nelson system that empties into Hudson Bay.

Red Deer River h ...

. Around 1870, the alliance between the Blackfoot and the Gros Ventre broke, and the latter began to look to their former enemies, the Southern Assiniboine (or Plains Assiniboine), for protection.

First contact with Europeans and the fur trade

Anthony Henday

Anthony Henday (fl. 1750–1762) was one of the first Europeans to explore the interior of what would eventually become western Canada. He ventured farther westward than any white man had before him.

As an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company ...

of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

(HBC) met a large Blackfoot group in 1754 in what is now Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

. The Blackfoot had established dealings with traders connected to the Canadian and English fur trade before meeting the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

in 1806. Lewis and Clark and their men had embarked on mapping the Louisiana Territory and upper Missouri River for the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

.

On their return trip from the Pacific Coast, Lewis and three of his men encountered a group of young Blackfoot warriors with a large herd of horses, and it was clear to Meriwether Lewis that they were not far from much larger groups of warriors. Lewis explained to them that the United States government wanted peace with all Indian nations, and that the US leaders had successfully formed alliances with other Indian nations. The group camped together that night, and at dawn there was a scuffle as it was discovered that the Blackfoot were trying to steal guns and run off with their horses while the Americans slept. In the ensuing struggle, one warrior was fatally stabbed and another shot by Lewis and presumed killed.Gibson, 23-29

In subsequent years, American mountain men

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s (with a peak population in the early 1840s). They were instrumental in opening up ...

trapping in Blackfoot country generally encountered hostility. When John Colter

John Colter (c.1770–1775 – May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813) was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Though party to one of the more famous expeditions in history, Colter is best remembered for explorations he made ...

, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, returned to Blackfoot country soon after, he barely escaped with his life. In 1809, Colter and his companion were trapping on the Jefferson River by canoe when they were surrounded by hundreds of Blackfoot warriors on horseback on both sides of the river bank. Colter's companion, John Potts, did not surrender and was killed. Colter was stripped of his clothes and forced to run for his life, after being given a head start (famously known in the annals of the West as "Colter's Run.") He eventually escaped by reaching a river five miles away and diving under either an island of driftwood

__NOTOC__

Driftwood is wood that has been washed onto a shore or beach of a sea, lake, or river by the action of winds, tides or waves.

In some waterfront areas, driftwood is a major nuisance. However, the driftwood provides shelter and fo ...

or a beaver dam

A beaver dam or beaver impoundment is a dam built by beavers to create a pond which protects against predators such as coyotes, wolves and bears, and holds their food during winter. These structures modify the natural environment in such a way t ...

, where he remained concealed until after nightfall. He trekked another 300 miles to a fort.

In the context of shifting tribal politics due to the spread of horses and guns, the Niitsitapi initially tried to increase their trade with the HBC traders in

In the context of shifting tribal politics due to the spread of horses and guns, the Niitsitapi initially tried to increase their trade with the HBC traders in Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

whilst blocking access to the HBC by neighboring peoples to the West. But the HBC trade eventually reached into what is now inland British Columbia.

By the late 1820s, his promptedthe Niitsitapiksi, and in particular the Piikani, whose territory was rich in beaver, otemporarily put aside cultural prohibitions and environmental constraints to trap enormous numbers of these animals and, in turn, receive greater quantities of trade items.

The HBC encouraged Niitsitapiksi to trade by setting up posts on the

The HBC encouraged Niitsitapiksi to trade by setting up posts on the North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

, on the northern boundary of their territory. In the 1830s the Rocky Mountain region and the wider Saskatchewan District were the HBC's most profitable, and Rocky Mountain House

Rocky Mountain House is a town in west-central Alberta, Canada. It is approximately west of Red Deer at the confluence of the Clearwater and North Saskatchewan Rivers, and at the crossroads of Highway 22 (Cowboy Trail) and Highway 11 (David T ...

was the HBC's busiest post. It was primarily used by the Piikani. Other Niitsitapiksi nations traded more in pemmican and buffalo skins than beaver, and visited other posts such as Fort Edmonton

Fort Edmonton (also named Edmonton House) was the name of a series of trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1795 to 1914, all of which were located on the north banks of the North Saskatchewan River in what is now central Alberta, ...

.

Meanwhile, in 1822 the American Fur Company entered the Upper Missouri region from the south for the first time, without Niitsitapiksi permission. This led to tensions and conflict until 1830, when peaceful trade was established. This was followed by the opening of Fort Piegan

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

as the first American trading post in Niitsitapi territory in 1831, joined by Fort MacKenzie in 1833. The Americans offered better terms of trade and were more interested in buffalo skins than the HBC, which brought them more trade from the Niitsitapi. The HBC responded by building Bow Fort (Peigan Post) on the Bow River

The Bow River is a river in Alberta, Canada. It begins within the Canadian Rocky Mountains and winds through the Alberta foothills onto the prairies, where it meets the Oldman River, the two then forming the South Saskatchewan River. These w ...

in 1832, but it was not a success.

In 1833, German explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied

Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied (23 September 1782 – 3 February 1867) was a German explorer, ethnologist and naturalist. He led a pioneering expedition to southeast Brazil between 1815–1817, from which the album ''Reise na ...

and Swiss painter Karl Bodmer

Johann Carl Bodmer (11 February 1809 – 30 October 1893) was a Swiss-French printmaker, etcher, lithographer, zinc engraver, draughtsman, painter, illustrator and hunter. Known as Karl Bodmer in literature and paintings, as a Swiss and French c ...

spent months with the Niitsitapi to get a sense of their culture. Bodmer portrayed their society in paintings and drawings.

Contact with the Europeans caused a spread of infectious diseases to the Niitsitapi, mostly cholera and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. In one instance in 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat, the ''St. Peter's'', was headed to Fort Union and several passengers contracted smallpox on the way. They continued to send a smaller vessel with supplies farther up the river to posts among the Niitsitapi. The Niitsitapi contracted the disease and eventually 6,000 died, marking an end to their dominance among tribes over the Plains. The Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

did not require or help their employees get vaccinated; the English doctor Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner, (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was a British physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines, and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

had developed a technique 41 years before but its use was not yet widespread.

Indian Wars

Like many other Great Plains Indian nations, the Niitsitapi often had hostile relationships with white settlers. Despite the hostilities, the Blackfoot stayed largely out of the Great Plains Indian Wars, neither fighting against nor scouting for the United States army. One of their friendly bands, however, was attacked by mistake and nearly destroyed by the US Army in the

Like many other Great Plains Indian nations, the Niitsitapi often had hostile relationships with white settlers. Despite the hostilities, the Blackfoot stayed largely out of the Great Plains Indian Wars, neither fighting against nor scouting for the United States army. One of their friendly bands, however, was attacked by mistake and nearly destroyed by the US Army in the Marias Massacre

The Marias Massacre (also known as the Baker Massacre or the Piegan Massacre) was a massacre of Piegan Blackfeet Native peoples which was committed by the United States Army as part of the Indian Wars. The massacre took place on January 23, 1870 ...

on 23 January 1870, undertaken as an action to suppress violence against settlers. A friendly relationship with the North-West Mounted Police and learning of the brutality of the Marias Massacre discouraged the Blackfoot from engaging in wars against Canada and the United States.

When the Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

, together with their Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

allies, were fighting the United States Army, they sent runners into Blackfoot territory, urging them to join the fight. Crowfoot

Crowfoot (1830 – 25 April 1890) or Isapo-Muxika ( bla, Issapóómahksika, italics=yes; syllabics: ) was a chief of the Siksika First Nation. His parents, (Packs a Knife) and (Attacked Towards Home), were Kainai. He was five years old when ...

, one of the most influential Blackfoot chiefs, dismissed the Lakota messengers. He threatened to ally with the NWMP to fight them if they came north into Blackfoot country again. News of Crowfoot's loyalty reached Ottawa and from there London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

; Queen Victoria