Blackbirding involves the

coercion of people through deception or

kidnapping to work as

slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people indigenous to the numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean during the 19th and 20th centuries. These blackbirded people were called

Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Queensland (Australia) in the 19 ...

or

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

. They were taken from places such as

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

,

Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

,

Niue

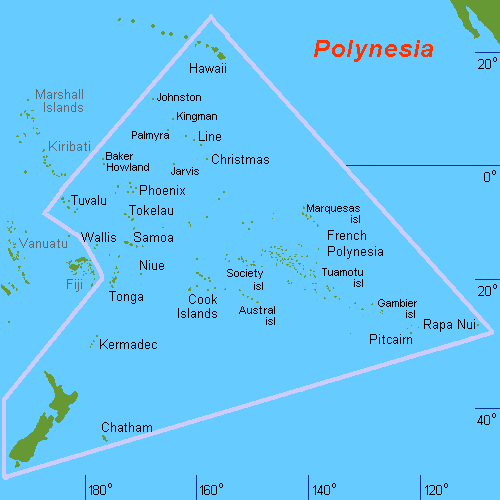

Niue (, ; niu, Niuē) is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean, northeast of New Zealand. Niue's land area is about and its population, predominantly Polynesian, was about 1,600 in 2016. Niue is located in a triangle between Tong ...

,

Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its ne ...

, the

Gilbert Islands,

Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-nor ...

, the Fiji islands and the islands of the

Bismarck Archipelago amongst others.

The owners, captains, and crews of the ships involved in the acquisition of these labourers were termed ''blackbirders''. The demand for this kind of cheap labour principally came from European colonists in

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

,

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

,

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

,

New Caledonia,

Fiji,

Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

and

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

, as well as plantations in

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

,

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and

Guatemala. Labouring on

sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

, cotton, and coffee plantations in these lands was the main usage of blackbirded labour, but they were also exploited in other industries. Blackbirding ships began operations in the Pacific from the 1840s which continued into the 1930s. Blackbirders from the Americas sought workers for their

haciendas and to mine the

guano deposits on the

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands () are a group of three small islands off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco. Since pre-Incan times they were of interest for their extensive guano deposits, but the supplies were mostly ...

,

while the blackbirding trade organised by colonists in places like Queensland, Fiji, and New Caledonia used the labourers at plantations, particularly those producing sugar cane.

Examples of blackbirding outside the South Pacific include the early days of the

pearling industry in Western Australia at

Nickol Bay

Nickol Bay is a bay between the Burrup Peninsula and Dixon Island, on the Pilbara coast in Western Australia.

Once alternatively spelled "Nicol Bay", it was named by John Septimus Roe for a sailor who was lost overboard during an expedition.

...

and

Broome, where

aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Isl ...

were blackbirded from the surrounding areas.

Practices similar to blackbirding continue to the present day. One example is the kidnapping and coercion, often at gunpoint, of indigenous peoples in

Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

to work as plantation labourers in the region. They are subjected to poor living conditions, are exposed to heavy

pesticide loads, and do hard labour for very little pay.

Etymology

The term may have been formed directly as a contraction of "blackbird catching"; "blackbird" was a slang term for the local indigenous people.

Australia

New South Wales

The first major blackbirding operation in the Pacific was conducted out of

Twofold Bay

Twofold Bay is an open oceanic embayment that is located in the South Coast region of New South Wales, Australia.

The bay was named by George Bass, for its shape of two bights. The northern bight is called Calle Calle Bay; while the souther ...

in

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. A shipload of 65

Melanesian labourers arrived in

Boyd Town on 16 April 1847 on board ''Velocity'', a vessel under the command of Captain Kirsopp and chartered by

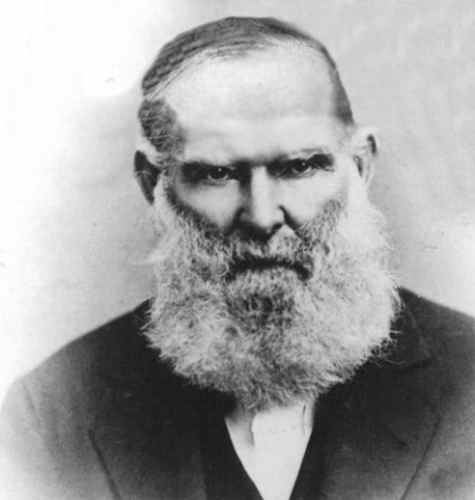

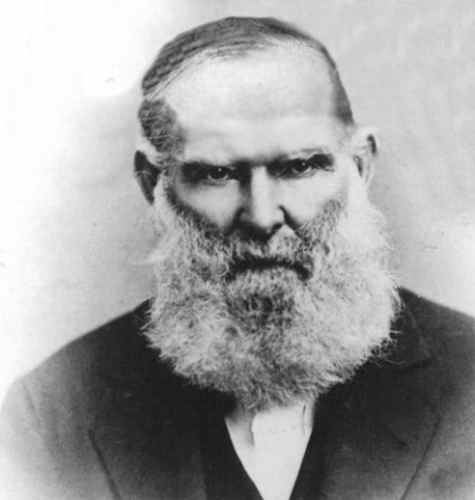

Benjamin Boyd

Benjamin Boyd (21 August 180115 October 1851) was a Scottish entrepreneur who became a major shipowner, banker, grazier, politician and slaver, exploiting South Sea Islander labour in the British colony of New South Wales.

Boyd became one ...

. Boyd was a Scottish colonist who wanted cheap labourers to work at his large pastoral leaseholds in the colony of

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. He financed two more procurements of South Sea Islanders, 70 of which arrived in

Sydney in September 1847, and another 57 in October of that same year. Many of these Islanders soon absconded from their workplaces and were observed starving and destitute on the streets of Sydney. Reports of violence, kidnap and murder used during the recruitment of these labourers surfaced in 1848 with a closed-door enquiry choosing not to take any action against Boyd or Kirsopp. The experiment of exploiting Melanesian labour was discontinued in Australia until

Robert Towns

Robert Towns (10 November 1794 – 11 April 1873) was a British master mariner who settled in Australia as a businessman, sandalwood merchant, colonist, shipowner, pastoralist, politician, whaler and civic leader. He was the founder of Townsvil ...

recommenced the practice in

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

in the early 1860s.

Queensland

The Queensland labour trade in

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

, or

Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Queensland (Australia) in the 19 ...

as they were commonly termed, was in operation from 1863 to 1908, a period of 45 years. Some 55,000 to 62,500 were brought to Australia,

[Tracey Flanagan, Meredith Wilkie, and Susanna Iuliano]

"Australian South Sea Islanders: A Century of Race Discrimination under Australian Law"

, Australian Human Rights Commission. most being recruited or blackbirded from islands in

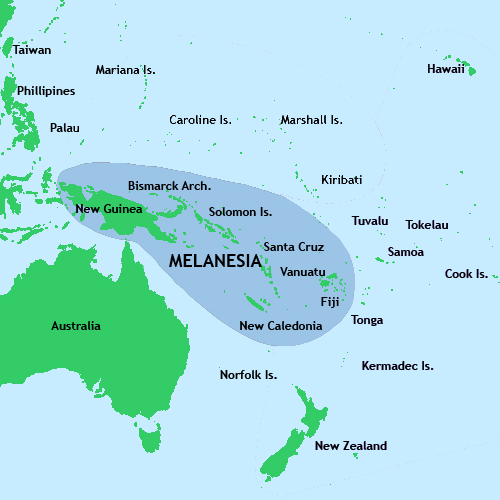

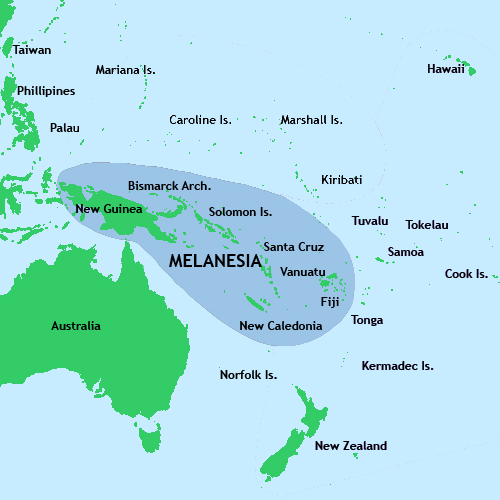

Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

, such as the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

(now

Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

), the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

and the islands around

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

. Although the process of acquiring these "indentured labourers" varied from violent kidnapping at gunpoint to relatively acceptable negotiation, most of the people affiliated with the trade were regarded as blackbirders.

The majority of those taken were male and around one quarter were under the age of sixteen. In total, approximately 15,000 Kanakas died while working in Queensland, a figure which does not include those who expired in transit or who were killed in the recruitment process. This represents a mortality rate of 30%, which is high considering most were only on three year contracts. It is also strikingly similar to the estimated 33% death rate of African slaves in the first three years of being imported to America.

Robert Towns and the first shipments

In 1863,

Robert Towns

Robert Towns (10 November 1794 – 11 April 1873) was a British master mariner who settled in Australia as a businessman, sandalwood merchant, colonist, shipowner, pastoralist, politician, whaler and civic leader. He was the founder of Townsvil ...

, a British

sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods for us ...

and

whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

merchant residing in

Sydney, wanted to profit from the world-wide cotton shortage due to the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. He bought a property he named

Townsvale on the

Logan River

The Logan River ( Yugambeh: ''Dugulumba'') is a perennial river located in the Scenic Rim, Logan and Gold Coast local government areas of the South East region of Queensland, Australia. The -long river is one of the dominant waterways in Sout ...

south of

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

, and planted of

cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

. Towns wanted cheap labour to harvest and prepare the cotton and decided to import Melanesian labour from the

Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands Province (French ''Province des îles Loyauté'') is one of three administrative subdivisions of New Caledonia encompassing the Loyalty Island (french: Îles Loyauté) archipelago in the Pacific, which are located northeast of ...

and the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

. Captain Grueber together with labour recruiter

Henry Ross Lewin aboard ''Don Juan'', brought 73

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

to the port of

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

in August 1863. Towns specifically wanted adolescent males. Recruitment and kidnapping was reportedly employed in obtaining these boys. Over the following two years, Towns imported around 400 more

Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in a wide area from Indonesia's New Guinea to as far East as the islands of Vanuatu and Fiji. Most speak either one of the many languages of the Austronesian language f ...

to Townsvale on one to three year terms of labour. They came on ''Uncle Tom'' (Captain Archer Smith) and ''Black Dog'' (Captain Linklater). In 1865, Towns obtained large land leases in

Far North Queensland and funded the establishment of the port of

Townsville

Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Queensland, Australia. With a population of 180,820 as of June 2018, it is the largest settlement in North Queensland; it is unofficially considered its capital. Estimated resident population, 3 ...

. He organised the first importation of South Sea Islander labour to that port in 1866. They came aboard ''Blue Bell'' under Captain Edwards. Towns paid his

Kanaka labourers in trinkets instead of cash at the end of their working terms. His agent claimed that blackbirded labourers were "savages who did not know the use of money" and therefore did not deserve cash wages. Apart from a small amount of Melanesian labour imported for the

beche-de-mer trade around

Bowen, Robert Towns was the primary exploiter of blackbirded labour up until 1867.

Expansion and legislation

The high demand for very cheap labour in the sugar and pastoral industries of

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, resulted in Towns' main labour recruiter, Henry Ross Lewin, and another recruiter by the name of John Crossley opening their services to other land-owners. In 1867, ''King Oscar'', ''Spunkie'', ''Fanny Nicholson'' and ''Prima Donna'' returned with close to 1,000 Kanakas who were offloaded in the ports of

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

,

Bowen and

Mackay Mackay may refer to:

*Clan Mackay, the Scottish clan from which the surname "MacKay" derives

Mackay may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Mackay Region, a local government area

** Mackay, Queensland, a city in the above region

*** Mackay Airpor ...

. This influx, together with information that the recently arrived labourers were being sold for £2 each and that kidnapping was at least partially used during recruitment, raised fears of a burgeoning new slave trade. These fears were realised when French officials in

New Caledonia complained that Crossley had stolen half the inhabitants of a village in

Lifou, and in 1868 a scandal evolved when Captain McEachern of ''Syren'' anchored in Brisbane with 24 dead islander recruits and reports that the remaining ninety on board were taken by force and deception. Despite the controversy, no action was taken against McEachern or Crossley.

Many members of the Queensland government were already either invested in the labour trade or had Kanakas actively working on their land holdings. Therefore, the 1868 legislation on the trade in the form of the Polynesian Labourers Act, that was brought in due to ''Syren'' debacle, requiring every ship to be licensed and carry a government agent to observe the recruitment process, was poor in protections and even more poorly enforced.

Government agents were often corrupted by bonuses paid for labourers 'recruited,' or blinded by alcohol, and did little or nothing to prevent sea-captains from tricking islanders on-board or otherwise engaging in kidnapping with violence.

The Act also stipulated that the Kanakas were to be contracted for no more than 3 years and be paid £18 for their work. This was an extremely low wage that was only paid at the end of their three years of work. Additionally, a system whereby the Islanders were heavily influenced to buy overpriced goods of poor quality at designated shops before they returned home, robbed them further. The Act, instead of protecting the South Sea Islanders, actually gave legitimacy to a kind of slavery in Queensland.

Certain officials in London were concerned enough with the situation to order a vessel of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

based at the

Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British, and later Australian, naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent.Dennis et al. 2008, p.53. Australia Station was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station, ...

in

Sydney to do a cruise of investigation. In 1869, under Captain George Palmer managed to intercept a blackbirding ship loaded with Islanders at

Fiji. under command of Captain Daggett and licensed in

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

to

Henry Ross Lewin, was described by Palmer as being fitted out "like an African slaver". Even though there was a government agent on board, the Islanders recruited appeared in poor condition and, having no understanding of English and no interpreter, had little idea of why they were being transported. Palmer seized the ship, freed the Kanakas and arrested both Captain Daggett and the ship's owner Thomas Pritchard for slavery. Daggett and Pritchard were taken to

Sydney to be tried but all charges were quickly dismissed and the prisoners discharged. Furthermore, Sir

Alfred Stephen, the Chief Justice of the

New South Wales Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of New South Wales is the highest state court of the Australian State of New South Wales. It has unlimited jurisdiction within the state in civil matters, and hears the most serious criminal matters. Whilst the Supreme Cour ...

found that Captain Palmer had illegally seized ''Daphne'' and ordered him to pay reparations to Daggett and Pritchard. No evidence or statements were taken from the Islanders. This decision, which overrode the obvious humanitarian actions of a senior officer of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, gave further legitimacy to the blackbirding trade out of Queensland and allowed it to flourish.

It also constrained the actions by naval commanders when dealing with incidents on the high seas and also crimes against the many missionaries working on the islands.

The Kanaka trade in the 1870s

Recruiting of

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

soon became an established industry with labour vessels from across eastern Australia obtaining Kanakas for both the

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

and

Fiji markets. Captains of such ships would get paid about 5 shillings per recruit in "head money" incentives, while the owners of the ships would sell the Kanakas from anywhere between £4 to £20 per head.

The Kanakas who were transported on ''Bobtail Nag'' had metal discs imprinted with a letter of the alphabet hung around their neck making for easy identification.

Maryborough and

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

became important centres for the trade with vessels such as ''Spunkie'', ''Jason'' and ''Lyttona'' making frequent recruiting journeys out of these ports. Reports of blackbirding, kidnap and violence were made against these vessels with Captain Winship of ''Lyttona'' being accused of kidnapping and importing Kanaka boys aged between 12 and 15 years for the plantations of

George Raff at

Caboolture. The

Queensland Governor

The governor of Queensland is the representative in the state of Queensland of the monarch of Australia. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governor performs constitutional and ceremonial funct ...

made enquiries and "found that there were a few islanders between fourteen and sixteen years of age, but that they, like all the others who accompanied them, had engaged without any pressure and were perfectly happy and contented". It was alleged by missionaries in the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

that one crew member of ''Spunkie'' murdered two recruits by shooting them, but the immigration agent Charles James Nichols who was on board the vessel denied this occurred.

Charges of kidnap were made against Captain John Coath of ''Jason''.

Only Captain Coath was brought to trial and, despite being found guilty, he was soon pardoned and allowed to re-enter the recruiting trade.

Up to 45 of the Kanakas brought in by Coath died on plantations around the

Mary River. Meanwhile, the famous recruiter Henry Ross Lewin was charged with the rape of a pubescent Islander girl. Despite strong evidence, Lewin was acquitted and the girl was later sold in Brisbane for £20.

By the 1870s, South Sea Islanders were being put to work not only in cane-fields along the Queensland coast but were also widely used as shepherds upon the large

sheep station

A sheep station is a large property ( station, the equivalent of a ranch) in Australia or New Zealand, whose main activity is the raising of sheep for their wool and/or meat. In Australia, sheep stations are usually in the south-east or sout ...

s in the interior and as pearl divers in the

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the Australian mai ...

. They were taken as far west as

Hughenden Hughenden may refer to:

*Hughenden, Queensland, a town in Australia

*Hughenden, Alberta, a village in central Alberta, Canada

*Hughenden Valley

Hughenden Valley (formerly called Hughenden or Hitchendon) is an extensive village and civil parish in ...

,

Normanton and

Blackall

Blackall is a rural town and locality in the Blackall-Tambo Region, Queensland, Australia. In the the locality of Blackall had a population of 1,416 people.

The town is the service centre for the Blackall-Tambo Region. The dominant industry ...

. A number of Islanders died, one by

scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

on the long journey from

Rockhampton to

Bowen Downs Station

Bowen Downs Station is a pastoral lease that has operated both as a cattle station and a sheep station.

It is located about east of Muttaburra and north west of Aramac in the outback of Queensland. It is watered by the Thomson River and t ...

. Captain Sadleir, the Police Magistrate of Tambo, stated that a prosecution would proceed "if the whipping was severe" and that "Sometimes a small amount of correction is necessary" When four Kanakas murdered Mr Gibbie and Mr Bell, two of them were tracked and captured by

Native Police

Australian native police units, consisting of Aboriginal troopers under the command (usually) of at least one white officer, existed in various forms in all Australian mainland colonies during the nineteenth and, in some cases, into the twentie ...

. When the owners of the properties they were labouring on went bankrupt, the Islanders would often either be abandoned or sold as part of the estate to a new owner. In the Torres Strait, Kanakas were left at isolated pearl fisheries such as the Warrior Reefs for years with little hope of being returned home. In this region, three ships used to procure pearl-shells and beche-de-mer, including ''Challenge'' were owned by

James Merriman who held the position of

Mayor of Sydney.

Poor conditions at the sugar plantations led to regular outbreaks of disease and death. The

Maryborough plantations and the labour vessels operating out of that port became notorious for high mortality rates of Kanakas. During the

measles epidemic of 1875, ships such as ''Jason'' arrived with Islanders either dead or infected with the disease. There were 30 deaths recorded of measles, followed by dysentery. From 1875 to 1880, at least 443 Kanakas died in the Maryborough region from gastrointestinal and pulmonary disease at a rate 10 times above average. The

Yengarie,

Yarra Yarra and Irrawarra plantations belonging to

Robert Cran were particularly bad. An investigation revealed that the Islanders were overworked, underfed, not provided with medical assistance and that the water supply was a stagnant drainage pond. At the port of

Mackay Mackay may refer to:

*Clan Mackay, the Scottish clan from which the surname "MacKay" derives

Mackay may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Mackay Region, a local government area

** Mackay, Queensland, a city in the above region

*** Mackay Airpor ...

, the labour schooner ''Isabella'' arrived with half the Kanakas recruited dying on the voyage from

dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, while Captain

John Mackay (after whom the city of

Mackay Mackay may refer to:

*Clan Mackay, the Scottish clan from which the surname "MacKay" derives

Mackay may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Mackay Region, a local government area

** Mackay, Queensland, a city in the above region

*** Mackay Airpor ...

is named), arrived at

Rockhampton in ''Flora'' with a cargo of Kanakas, of which a considerable number were in a dead or dying condition.

As the blackbirding activities increased and the detrimental results became more understood, resistance by the Islanders to this recruitment system grew. Labour vessels were regularly repelled from landing at many islands by local people. Recruiter, Henry Ross Lewin, was killed at

Tanna Island

Tanna (sometimes misspelled ''Tana'') is an island in Tafea Province of Vanuatu.

Name

The name ''Tanna'', first cited by James Cook, is derived from the word ''tana'' in the Kwamera language, meaning "earth".

Etymologically, ''Tanna'' goes b ...

, the crew of ''May Queen'' were killed at

Pentecost Island, while the captain and crew of ''Dancing Wave'' were killed at the

Nggela Islands. Blackbirders would sometimes make their vessels look like missionary ships, deceiving then kidnapping local Islanders. This led to violence against the missionaries themselves, the best example being the killing of Anglican missionary

John Coleridge Patteson

John Coleridge Patteson (1 April 1827 – 20 September 1871) was an English Anglican bishop, missionary to the South Sea Islands, and an accomplished linguist, learning 23 of the islands' more than 1,000 languages.

In 1861, Patteson was s ...

in 1871 at

Nukapu. A few days before his death, one of the local men had been killed and five others abducted by crew of ''Margaret Chessel'' who pretended to be missionaries.

Patteson may also have been killed due to his desire to take the Islanders' children to a distant mission school and that he had disrupted the local patriarchal hierarchy.

At other islands blackbirding vessels, such as ''Mystery'' under Captain Kilgour, attacked villages, shooting the residents and burning their houses. Ships of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

were also called upon to investigate the deeds and deliver appropriate punishment upon islands involved in killings of blackbirding crews and missionaries. For example,

HMS Rosario in 1871 whilst investigating the Bishop Patteson murder and other conflicts between islanders, settlers and missionaries as the Commander describes in his book. And later under Captain de Houghton and under Commodore

John Crawford Wilson conducted several missions in the late 1870s that involved

naval bombardment

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by the ...

of villages, raids by marines, burning of houses, destruction of crops and the hanging of an Islander from the

yardarms

A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber or steel or from more modern materials such as aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards, the term is usually used to desc ...

. One of these expeditions involved the assistance of the armed crew of the blackbirding vessel ''Sybil'' commanded by Captain Satini. Furthermore, two

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

were hanged in

Maryborough for the rape and attempted murder of a white woman, these being the first legal executions in that town.

Early 1880s: Intense conflict

The violence and death surrounding the Queensland blackbirding trade intensified in the early 1880s. Local communities in the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

and the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

had increased access to modern firearms which made their resistance to the blackbirders more robust. Well known vessels that experienced mortality amongst their crews while attempting to recruit Islanders included ''Esperanza'' at

Simbo

Simbo is an island in Solomon Islands; it is located in the Western Province. It was known to early Europeans as Eddystone Island.

Geography

Simbo is actually two main islands, one small island called Nusa Simbo separated by a saltwater lagoon f ...

, ''Pearl'' at

Rendova Island, ''May Queen'' at

Ambae Island, ''Stormbird'' at

Tanna, ''Janet Stewart'' at

Malaita and ''Isabella'' at

Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region o ...

amongst others. Officers of

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

warships attempting punitive action were not exempt as targets with Lieutenant Bower and five crew of being killed in the

Nggela Islands and Lieutenant Luckcraft of being shot dead at

Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region o ...

. Numerous punitive expeditions were carried out by Royal Navy warships based at the

Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British, and later Australian, naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent.Dennis et al. 2008, p.53. Australia Station was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station, ...

. under Captain W.H. Maxwell went on an extensive

punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

,

shelling and destroying numerous villages, while

marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

of executed various Islanders suspected of killing white men. Captain Dawson of led a mission to

Ambae Island, killing a chief suspected of murdering blackbirders, while went on a "savage-hunting expedition" throughout the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

which resulted in no casualties on either side. At

Ambrym, the marines of under Commander Moore, raided and burned down a village in retaliation for the killing of Captain Belbin of the blackbirding ship ''Borough Belle''. Likewise, patrolled the islands, protecting the crews of blackbirding vessels such as ''Ceara'' from mutinies of the labour recruits.

''The Age'' 1882 slave trade exposé

In 1882, the

Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

newspaper ''

The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory ...

'' published an eight-part

series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used in ...

written by journalist and future physician

George E. Morrison, who had sailed, undercover, for the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

, while posing as crew of the brigantine

slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

, ''Lavinia'', as it made cargo of

Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Queensland (Australia) in the 19 ...

. "A Cruise in a Queensland Slaver. By a Medical Student" was written in a tone of wonder, expressing "only the mildest criticism"; six months later, Morrison "revised his original assessment", describing details of ''Lavinia'' blackbirding operation, and sharply denouncing the slave trade in Queensland. His articles, letters to the editor, and ''The Age'' editorials, led to expanded government intervention.

Mid 1880s: Shifting of recruitment from the New Guinea islands

The usual recruiting grounds of the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

and

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

became too dangerous and too expensive to obtain labour from. However, the well-populated islands around

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

were soon targeted for recruiting as these people were less aware of the blackbirding system and had less access to firearms. A new rush for labour from these islands began, with

James Burns and

Robert Philp

Sir Robert Philp, (28 December 1851 – 17 June 1922) was a Queensland businessman and politician who was Premier of Queensland from December 1899 to September 1903 and again from November 1907 to February 1908.

Early life

Philp was born in ...

of

Burns Philp & Co. purchasing several well-known blackbirding ships to quickly exploit the human resource in this region.

Plantation owners such as Robert Cran also bought vessels and made contact with missionaries like Samuel MacFarlane in the New Guinea area to help facilitate the acquisition of cheap workers. Kidnapping, forced recruitment, killings, false payment and the enslavement of children was again the typical practice. Captain William T. Wawn, a famous blackbirder working for the

Burns Philp

Burns Philp (properly Burns, Philp & Co, Limited) was once a major Australian shipping line and merchant that operated in the South Pacific. When the well-populated islands around New Guinea were targeted for blackbirding in the 1880s, a new ...

company on the ship ''Lizzie'', freely acknowledged in his memoirs that he took boatloads of young boys with no information given about contracts, pay or the nature of the work.

Up to 530 boys were recruited per month from these islands, most of whom were transported to the new large company plantations in

Far North Queensland, such as the

Victoria Plantation owned by

CSR. This phase of the trade was very profitable, with Burns Philp selling each recruit for around £23.

Many of them could not speak any English and died on these plantations at a rate of up to 1 in every 5 from disease, violence and neglect.

In April 1883, the

Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

,

Thomas McIlwraith

Sir Thomas McIlwraith (17 May 1835 – 17 July 1900) was for many years the dominant figure of colonial politics in Queensland. He was Premier of Queensland from 1879 to 1883, again in 1888, and for a third time in 1893. In common with most po ...

attempted to annex

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

to be part of Queensland. This was rejected by the British

Colonial Secretary mostly because of fears that it would expose even more of its inhabitants to be forcibly taken to work and possibly die in Queensland. The large influx of New Guinea labourers also sparked concern from

white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

anti-immigration groups, which led to the election in late 1883 of

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, (21 June 1845 – 9 August 1920) was an Australian judge and politician who served as the inaugural Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1903 to 1919. He also served a term as Chief Justice of Queensland and t ...

on an anti-Kanaka policy platform.

Griffith quickly banned recruitment from the New Guinea islands and spearheaded a number of high-profile criminal cases against blackbirding crews operating in the area. The crew of ''Alfred Vittery'' were charged with the murder of

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

, while Captain Joseph Davies of ''Stanley'', Captain Millman of ''Jessie Kelly'', Captain Loutit of ''Ethel'' as well as the owners of ''Forest King'' were all charged with kidnapping. All of these cases, despite strong evidence against them, resulted in acquittal. Charges of neglect resulting in death against plantation managers were also made. For example, Mr Melhuish of the

Yeppoon Sugar Plantation was tried, but even though he was found responsible, the judge involved imposed only the minimum £5 fine and wished it could be an even lesser amount. During a riot at the

Mackay Mackay may refer to:

*Clan Mackay, the Scottish clan from which the surname "MacKay" derives

Mackay may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Mackay Region, a local government area

** Mackay, Queensland, a city in the above region

*** Mackay Airpor ...

racetrack

A race track (racetrack, racing track or racing circuit) is a facility built for racing of vehicles, athletes, or animals (e.g. horse racing or greyhound racing). A race track also may feature grandstands or concourses. Race tracks are also use ...

, several

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

were beaten to death by mounted white men wielding

stirrup irons. Only one man, George Goyner, was convicted and received a minor punishment of two months imprisonment.

The ''Hopeful'' case, Royal Commission and planter compensation

In 1884, in one specific case, a significant judicial punishment was imposed on the blackbirders. This was in regards to the crew of ''Hopeful'' vessel which was owned by

Burns Philp

Burns Philp (properly Burns, Philp & Co, Limited) was once a major Australian shipping line and merchant that operated in the South Pacific. When the well-populated islands around New Guinea were targeted for blackbirding in the 1880s, a new ...

. Captain Lewis Shaw and four crew were charged and convicted of

kidnapping people from the

Bismarck Archipelago, while the recruiter Neil McNeil and the

boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervise ...

were charged and convicted of murdering a number of Islanders. The kidnappers received jail terms of 7 to 10 years, while McNeil and the boatswain were sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment. Despite evidence showing that at least 38 Islanders had been killed by ''Hopeful'' crew, all the prisoners (except for one who died in jail) were released in 1890 in response to a massive public petition signed by 28,000 Queenslanders.

This case sparked a Royal Commission into the recruitment of Islanders from which the

Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

concluded that it was no better than the African slave trade, and in 1885 the vessel S.S. ''Victoria'' was commissioned by the

Government of Queensland

The Queensland Government is the democratic administrative authority of the Australian state of Queensland. The Government of Queensland, a parliamentary constitutional monarchy was formed in 1859 as prescribed in its Constitution, as amended fr ...

to return 450 New Guinea Islanders to their homelands. Just like the global slave trade, the plantation owners, instead of being held criminally responsible, were financially compensated by the government for the loss of these returned workers.

Fourteen sugar companies and individual planters including

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company and David Adolphus Louis, took the Queensland Government to court to demand financial recompense and were collectively awarded £18,500. This is despite consistent evidence given in court of each plantation recording labourer death rates of up to 60% over the term of their servitude.

The later years of recruiting

Forceful recruitment of South Sea Islanders persisted in the New Guinea region, as well as in the Solomons and the New Hebrides islands, as did the high death rates of these labourers at Queensland plantations. At the

Yeppoon Sugar Company, deliberate poisonings of Kanakas also occurred and when this plantation was later put up for sale, the Islander labourers were included as part of the estate. Resistance and conflict also continued. For instance, at

Malaita three crew members of the recruiting vessel ''Young Dick'' were killed together with about a dozen Islanders in a skirmish, while at

Paama a large gun battle between the residents and the crew of ''Eliza Mary'' occurred. This ship later sank during a

cyclone causing the drowning deaths of 47 Kanakas. The policy of extensive

punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

s carried out by the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

against the Islanders persisted as well. The official report of the lengthy mission of which bombarded and burnt numerous villages in 1885 was kept secret. also bombarded numerous villages in punitive expeditions which elicited condemnation from some sections of the media.

Legislation was passed to end the South Sea Islander labour trade in 1890 but it was not effectively enforced and it was officially recommenced in 1892. Reports such as those by

Joe Melvin, an investigative journalist who in 1892 joined the crew of Queensland blackbirding ship ''Helena'' and found no instances of intimidation or misrepresentation and concluded that the Islanders recruited did so "willingly and cannily", helped the plantation owners secure the resumption of the trade. ''Helena'' under Captain A.R. Reynolds, transported Islanders to and from

Bundaberg and in this region there was a very large mortality rate of Kanakas in 1892 and 1893. South Sea Islanders made up 50% of all deaths in this period even though they only made up 20% of the total population in the Bundaberg area. The deaths were due to the hard manual labour and diseases such as

dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

,

influenza and

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

.

In the 1890s, other important recruiting vessels were ''Para'', ''Lochiel'', ''Nautilus'', ''Rio Loge'', ''Roderick Dhu'' and ''William Manson''. Joseph Vos, a well known blackbirder for many years and the captain of ''William Manson'', would use

phonographic recordings and enlarged photographs of relatives of Islanders to induce recruits on board his vessel. Vos and his crew were involved in killings, stealing women and setting fire to villages and were charged with

kidnapping.

However, they were found not guilty and released. ''Roderick Dhu'', a vessel owned by the sugar magnate Robert Cran, was another ship regularly involved in blackbirding investigations and conflict with Islanders. In 1890, it was involved in the shooting of people at

Ambae Island, and evidence of kidnapping by the crew was later published. In 1893, conflict with Islanders at

Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region o ...

resulted in the death of a crew member of ''Roderick Dhu''.

Repatriation

In 1901, the government of the newly federated British colonies of Australia legislated the "Regulation, Restriction and Prohibition of the Introduction of Labourers from the Pacific Islands" bill, better known as the

Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901. This Act, which was part of a larger

White Australia policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

, made it illegal to import

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

after March 1904 and mandated for the forcible deportation of all Islanders from Australia after 1906.

Strong lobbying from Islander residents in Australia forced some exemptions to be made, for example, those who were married to an Australian, who owned land or who had been living for 20 years in Australia were exempt from compulsory repatriation. However, many Islanders were not made aware of these exemptions. Around 4000 to 7500 were deported in the period 1906 to 1908, while approximately 1600 remained in Australia.

The

Burns Philp

Burns Philp (properly Burns, Philp & Co, Limited) was once a major Australian shipping line and merchant that operated in the South Pacific. When the well-populated islands around New Guinea were targeted for blackbirding in the 1880s, a new ...

company won the contract to deport the Islanders and those taken back to the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

were distributed to their home islands by vessels of Lever's Pacific Plantations company. Deported Solomon Islanders who were unable to go to their villages of origin or who were born in Australia, were often put to work in plantations in these islands. In some localities, serious conflict between these workers and white colonists in the Solomon Islands ensued. Around 350 of the South Sea Islanders banished from Queensland were transferred to plantations in

Fiji.

At least 27 of these died while being transported.

Today, the descendants of those who remained are officially referred to as Australian

South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

. A 1992 census of Australian South Sea Islanders reported around 10,000 descendants living in Queensland.

In the 2016 census, 6830 people in Queensland declared that they were descendants of

South Sea Islander

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

labourers.

Seasonal workers in the 21st century

In 2012, the Australian government introduced a seasonal worker scheme under the 416 and 403 visas to bring in Pacific Islander labour to work in the agricultural industry performing tasks such as picking fruit. By 2018, around 17,320 Islanders, mostly from

Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

,

Fiji and

Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, had been employed with the majority being placed on farms in

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. Workers under this programme have often been subject to working long hours in extreme temperatures and being forced to live in squalid conditions. Poor access to clean water, adequate food and medical assistance has resulted in several deaths. These reports, together with allegations of workers receiving as little as $10 a week after rent and transport deductions, resulted in the "Harvest Trail Inquiry" into the conditions of migrant horticultural workers. This inquiry confirmed widespread exploitation, intimidation and underpayment of workers with at least 55% of employers being non-compliant in regard to payments and conditions. It found many workers were contracted under a "piece rate" of pay with no written agreement and no minimum hourly rate (as is typical for Australian seasonal agricultural workers). Even though some wages were recovered and a number of employers and contractors were fined, the inquiry found that much more regulation was needed. Despite this report, the government expanded the programme in 2018 with the Pacific Labour Scheme which includes three-year contracts. Strong parallels have been drawn with the working conditions observed under this programme to those of blackbirded Pacific Islander labourers in the 19th Century.

The introduction of the ''Modern Slavery Act 2018'' into Australian law was partly based upon concerns of slavery being evident in the Queensland agricultural sector. Some commentators have also drawn parallels between blackbirding and the early 21st-century recruitment of labour under the (unconnected)

457 visa scheme.

Western Australia

The early days of the

pearling industry in Western Australia at

Nickol Bay

Nickol Bay is a bay between the Burrup Peninsula and Dixon Island, on the Pilbara coast in Western Australia.

Once alternatively spelled "Nicol Bay", it was named by John Septimus Roe for a sailor who was lost overboard during an expedition.

...

and

Broome, saw

Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Isl ...

blackbirded from the surrounding areas.

After settlement the Aborigines were used as slave labour in the emerging commercial industry.

During the early 1870s,

Francis Cadell became involved in

whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

,

trading

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

,

pearling and blackbirding in

North-West Australia. Cadell and others became notorious for their coercion, capture and sale of

Aboriginal people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

as slaves.

The slaves were often detained temporarily at camps known as ''

barracoon

A barracoon (a corruption of Portuguese ''barracão'', an augmentative form of the Catalan loanword ''barraca'' ('hut') through Spanish ''barracón'') is a type of barracks used historically for the internment of slaves or criminals.

In the Atl ...

s'' on

Barrow Island Barrow Island may refer to:

* Barrow Island (Western Australia), Australia

* Barrow Island (Queensland), Australia

* Barrow Island, Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow Island is an area and electoral ward of Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria, England. Origina ...

, offshore.

In 1875 magistrate Robert Fairbairn was sent to investigate pearling conditions at

Shark Bay, following reports that people, described as

Malays, employed by Cadell and

Charles Broadhurst were unpaid, unable to return home and some had starved to death. Fairbairn held that Cadell had not paid 10 Malays from the time they were engaged at

Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

in 1874 and he was required to pay the 10 Malays plus an additional 4 months wages as amends for the lack of food, totaling £198. 14s. 4d. They received just £16. 16s. from the sale of Cadell's property at Shark Bay as Cadell had left the Colony of Western Australia some months previously. Broadhurst was also found to have underpaid 18 Malays totaling £183. 4s. 2d. however the judgement was set aside by the

Supreme Court on the technicality that Broadhurst had not been given proper notice of the claim.

Fiji

Before annexation (1865 to 1874)

The blackbirding era began in

Fiji on 5 July 1865 when

Ben Pease received the first licence to transport 40 labourers from the

New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

to

Fiji in order to work on cotton plantations. The

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

had cut off the supply of cotton to the international market and cultivation of this

cash crop in Fiji was potentially an extremely profitable business. Thousands of Anglo-American and Anglo-Australian planters flocked to Fiji to establish plantations and the demand for cheap labour boomed. Transportation of

Kanaka labour to Fiji continued up until 1911 when it became prohibited by law. A probable total of around 45,000 Islanders were taken to work in Fiji during this 46-year period with approximately a quarter of these dying while under their term of labour.

Albert Ross Hovell, son of the noted explorer

William Hilton Hovell, was a prominent blackbirder in the early years of the Fijian labour market. In 1867 he was captain of ''Sea Witch'', recruiting men and boys from

Tanna and

Lifou. The following year, Hovell was in command of ''Young Australian'' which was involved in an infamous voyage resulting in charges of murder and slavery being laid. After being recruited, at least three Islanders were shot dead aboard the vessel and the rest sold in

Levuka

Levuka () is a town on the eastern coast of the Fijian island of Ovalau, in Lomaiviti Province, in the Eastern Division of Fiji. Prior to 1877, it was the capital of Fiji. At the census in 2007, the last to date, Levuka town had a population ...

for £1,200. Hovell and his

supercargo

A supercargo (from Spanish ''sobrecargo'') is a person employed on board a vessel by the owner of cargo carried on the ship. The duties of a supercargo are defined by admiralty law and include managing the cargo owner's trade, selling the merchand ...

, Hugo Levinger, were arrested in Sydney in 1869, found guilty by jury and sentenced to death. This was later commuted to life imprisonment but both were discharged from prison only after a couple of years.

In 1868 the Acting British Consul in Fiji,

John Bates Thurston

Sir John Bates Thurston (31 January 1836 – 7 February 1897) was a British colonial official who served Fiji in a variety of capacities, including Premier of the Kingdom of Viti (before the islands were ceded to the United Kingdom) and later ...

, brought only minor regulations upon the trade through the introduction of a licensing system for the labour vessels. Melanesian labourers were generally recruited for a term of three years at a rate of three pounds per year and issued with basic clothing and rations. The payment was half of that offered in

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

and like that colony was only given at the end of the three-year term usually in the form of poor quality goods rather than cash. Most Melanesians were recruited by combination of deceit and violence, and then locked up in the ship's hold to prevent escape. They were sold in Fiji to the colonists at a rate of £3 to £6 per head for males and £10 to £20 for females. After the expiry of the three-year contract, the government required captains to transport the surviving labourers back to their villages, but many were disembarked at places distant from their homelands.

A notorious incident of the blackbirding trade was the 1871 voyage of the

brig ''Carl'', organised by Dr James Patrick Murray,

[R. G. Elmslie, 'The Colonial Career of James Patrick Murray', ''Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery'', (1979) 49(1):154-62] to recruit labourers to work in the plantations of Fiji. Murray had his men reverse their collars and carry black books, so to appear to be church

missionaries. When islanders were enticed to a religious service, Murray and his men would produce guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the voyage Murray and his crew shot about 60 islanders. He was never brought to trial for his actions, as he was given immunity in return for giving evidence against his crew members.

The captain of ''Carl'', Joseph Armstrong, along with the mate Charles Dowden were sentenced to death, which was later commuted to life imprisonment.

Some Islanders brought to Fiji against their will demonstrated desperate actions to escape from their situation. Some groups managed to overpower the crews of smaller vessels to take command of these ships and attempt to sail back to their home islands. For example, in late 1871, Islanders aboard ''Peri'' being transported to a plantation on a smaller Fijian island, freed themselves, killed most of the crew and took charge of the vessel. Unfortunately, the ship was low in supplies and was blown westward into the open ocean where they spent two months adrift. Eventually, ''Peri'' was spotted by Captain

John Moresby aboard near to

Hinchinbrook Island

Hinchinbrook Island (or Pouandai to the Biyaygiri people) is an island in the Cassowary Coast Region, Queensland, Australia. It lies east of Cardwell and north of Lucinda, separated from the north-eastern coast of Queensland by the narrow H ...

off the coast of

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. Only thirteen of the original eighty kidnapped Islanders were alive and able to be rescued.

Labour vessels involved in this period of blackbirding for the Fijian market also included ''Donald McLean'' under the command of captain McLeod, and ''Flirt'' under captain McKenzie who often took people from

Erromango

Erromango is the fourth largest island in the Vanuatu archipelago. With a land area of it is the largest island in Tafea Province, the southernmost of Vanuatu's six administrative regions.

Name

The Exonym and endonym, endonym for Erromango in Er ...

. Captain Martin of ''Wild Duck'' stole people from

Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region o ...

, while other ships such as ''Lapwing'', ''Kate Grant'', ''Harriet Armytage'' and ''Frolic'' also participated in the kidnapping trade. The famous blackbirder,

Bully Hayes

William Henry "Bully" Hayes (1827 or 1829 – 31 March 1877) was a notorious American ship's captain who engaged in blackbirding in the 1860s and 1870s.James A. Michener & A. Grove Day, ''Bully Hayes, South Sea Buccaneer'', in ''Rascals in Parad ...

kidnapped Islanders for the Fiji market in his

Sydney-registered

schooner, ''Atlantic''. Many captains engaged in violent means to obtain the labourers. The crews of ''Margaret Chessel'', ''Maria Douglass'' and ''Marion Renny'' were involved in fatal conflict with various Islanders. Captain Finlay McLever of ''Nukulau'' was arrested and tried in court for kidnapping and assault but was discharged due to a legal technicality.

The passing of the Pacific Islanders Protection Act in 1872 by the British government was meant to improve the conditions for the Islanders but instead it legitimised the labour trade and the treatment of the blackbirded Islanders upon the Fiji plantations remained appalling. In his 1873 report, the British Consul to Fiji, Edward March, outlined how the labourers were treated as slaves. They were given insufficient food, subjected to regular beatings and sold on to other colonists. If they became rebellious they were either imprisoned by their owners or sentenced by magistrates (who were also plantation owners) to heavy labour. The planters were allowed to inflict punishment and restrain the Islanders as they saw fit and young girls were openly bartered for and sold into

sexual slavery. Many workers were not paid and those who survived and were able to return to their home islands were regarded as lucky.

After annexation (1875 to 1911)

The British annexed Fiji in October 1874 and the labour trade in Pacific Islanders continued as before. In 1875, the year of the catastrophic

measles epidemic, the chief medical officer in Fiji, Sir

William MacGregor

Sir William MacGregor, (20 October 1846 – 3 July 1919)R. B. Joyce,', ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974, pp 158–160. Retrieved 29 September 2009 was a Lieutenant-Governor of British New Guine ...

, listed a mortality rate of 540 out of every 1,000 Islander labourers. The

Governor of Fiji

Fiji was a British Crown colony from 1874 to 1970, and an independent dominion in the Commonwealth from 1970 to 1987. During this period, the head of state was the British monarch, but in practice his or her functions were normally exercised loca ...

,

Sir Arthur Gordon, endorsed not only the procuring of Kanaka labour but became an active organiser in the plan to expand it to include mass importation of indentured

coolie

A coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a term for a low-wage labourer, typically of South Asian or East Asian descent.

The word ''coolie'' was first popularized in the 16th century by European traders acros ...

workers from India. The establishment of the

Western Pacific High Commission in 1877, which was based in Fiji, further legitimised the trade by imposing British authority upon most people living in Melanesia.

Violence and kidnapping persisted with Captain Haddock of ''Marion Renny'' shooting people at

Makira

The island of Makira (also known as San Cristobal and San Cristóbal) is the largest island of Makira-Ulawa Province in the Solomon Islands. It is third most populous island after Malaita and Guadalcanal, with a population of 55,126 as of 2020. ...

and burning their villages. Captain John Daly of ''Heather Belle'' was convicted of kidnapping and jailed but was soon allowed to leave Fiji and return to

Sydney. Many deaths continued to occur upon the blackbirding vessels bound for Fiji, with perhaps the worst example from this period being that which occurred on ''Stanley''. This vessel was chartered by the colonial British government in Fiji to conduct six recruiting voyages for the Fiji labour market. Captain James Lynch was in command and on one of these voyages he ordered 150 recruits to be locked in the ship's hold during an extended period of stormy weather. By the time the ship arrived in

Levuka

Levuka () is a town on the eastern coast of the Fijian island of Ovalau, in Lomaiviti Province, in the Eastern Division of Fiji. Prior to 1877, it was the capital of Fiji. At the census in 2007, the last to date, Levuka town had a population ...