Black genocide conspiracy theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

The Cold War raised American concerns about Communist expansionism. The CRC petition was viewed by the US government as being against America's best interests with regard to fighting Communism. The petition was ignored by the UN; many of the charter countries looked to the US for guidance and were not willing to arm the enemies of the US with more propaganda about its failures in domestic racial policy. American responses to the petition were various: Radio journalist Drew Pearson spoke out against the supposed "Communist propaganda" before it was presented to the UN.

Professor Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer who had helped draft the UN Genocide Convention, said that the CRC petition was a misguided effort which drew attention away from the

The Cold War raised American concerns about Communist expansionism. The CRC petition was viewed by the US government as being against America's best interests with regard to fighting Communism. The petition was ignored by the UN; many of the charter countries looked to the US for guidance and were not willing to arm the enemies of the US with more propaganda about its failures in domestic racial policy. American responses to the petition were various: Radio journalist Drew Pearson spoke out against the supposed "Communist propaganda" before it was presented to the UN.

Professor Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer who had helped draft the UN Genocide Convention, said that the CRC petition was a misguided effort which drew attention away from the

Ideas of reproductive fitness were still at the center of American family planning in the 1960s. Physicians preferred to prescribe the Pill to white middle-class women and the IUD to poor women, especially poor women of color, because the IUD granted them greater control over "unfit" women's behavior. Guttmacher viewed the IUD as an effective method of contraception for individuals in "underdeveloped areas where two things are lacking: one, money and the other sustained motivation.

Once the method was approved for use in the United States, the majority of Pill users were white and middle class women. In part, this trend reflects doctors' preference to prescribe the Pill to members of this population, and it also reflects the cost of the drug. Until the late 1960s, the Pill was prohibitively expensive for working-class and poor women.

After President

Ideas of reproductive fitness were still at the center of American family planning in the 1960s. Physicians preferred to prescribe the Pill to white middle-class women and the IUD to poor women, especially poor women of color, because the IUD granted them greater control over "unfit" women's behavior. Guttmacher viewed the IUD as an effective method of contraception for individuals in "underdeveloped areas where two things are lacking: one, money and the other sustained motivation.

Once the method was approved for use in the United States, the majority of Pill users were white and middle class women. In part, this trend reflects doctors' preference to prescribe the Pill to members of this population, and it also reflects the cost of the drug. Until the late 1960s, the Pill was prohibitively expensive for working-class and poor women.

After President  From 1965 to 1970, black militant males, especially younger men from poverty-stricken areas, spoke out against birth control by denouncing it as part of a plot to commit a genocide against black people. The Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam were the strongest critics of birth control. The Black Panther Party identified a number of injustices as factors which contributed to black genocide, including social ills that were more serious in black populations than they were in white populations, such as drug abuse, prostitution and

From 1965 to 1970, black militant males, especially younger men from poverty-stricken areas, spoke out against birth control by denouncing it as part of a plot to commit a genocide against black people. The Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam were the strongest critics of birth control. The Black Panther Party identified a number of injustices as factors which contributed to black genocide, including social ills that were more serious in black populations than they were in white populations, such as drug abuse, prostitution and

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, black genocide is the notion that the mistreatment of African Americans by both the United States government and white Americans

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

, both in the past and the present, amounts to genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

. The decades of lynchings and long-term racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

were first formally described as genocide by a now-defunct organization, the Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Li ...

, in a petition which it submitted to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

in 1951. In the 1960s, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

accused the US government of engaging in a genocide against black people, citing long-term injustice, cruelty, and violence against blacks by whites.

Some accusations of genocide have been described as conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

. In response to the War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national ...

legislation which was proposed by President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

in the mid-1960s, legislation which included the public funding of the Pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. The pill contains two important hormones: proges ...

for the poor, at the first Black Power Conference, which was held in July 1967, family planning ( birth control) was said to be "black genocide." After abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

was more widely legalized in 1970, some black militants named abortion specifically as part of the conspiracy theory. Most African-American women were not convinced of a conspiracy, and rhetoric about race genocide faded. However, 1973 media revelations about decades of government-sponsored compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

led some to say that this was part of a plan for black genocide. Other events around this time period were also declared methods of black genocide, such as the War on Drugs, War on Crime, and War on Poverty, which had detrimental effects on the black community.

During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, the increasing use of black soldiers in combat provided another basis for the accusation that the government was engaging in a "black genocide." In recent decades, the disproportionately high black prison population has also been cited in support of the claim that a black genocide is being committed.

Slavery as genocide

Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in general and the Atlantic slave trade in particular was an archetypal example of a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

in the 19th century, a larger category of crimes that was expanded when genocide was included in it in the 20th century. George Washington Williams

George Washington Williams (October 16, 1849 – August 2, 1891) was a soldier in the American Civil War and in Mexico before becoming a Baptist minister, politician, lawyer, journalist, and writer on African-American history.

He served in the ...

popularized the concept of crimes against humanity with regard to the history of slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sl ...

and during the Congo Free State propaganda war of the 1890s, the "laws of humanity" were included in the Martens Clause

The Martens Clause ( pronounced ) was introduced into the preamble to the 1899 Hague Convention II – Laws and Customs of War on Land.

__NOTOC__

The clause took its name from a declaration read by Friedrich Martens, the delegate of Russia at ...

of the Hague Conventions and as a result, they were legally enshrined in international law.

Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

scholar Adam Jones characterizes the mass death of millions of Africans during the Atlantic slave trade as a genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

due to the fact that it was " one of the worst holocausts in human history" because it resulted in 15 to 20 million deaths according to one estimate, and he has also stated that arguments to the contrary, such as the argument that "it was in slave owners' interest to keep slaves alive, not exterminate them", is "mostly sophistry", due to the fact that "the killing and destruction were intentional, whatever the incentives to preserve survivors of the Atlantic passage for labor exploitation. To revisit the issue of intent already touched on: If an institution is deliberately maintained and expanded by discernible agents, though all are aware of the hecatombs of casualties it is inflicting on a definable human group, then why should this not qualify as genocide?"

In his book, ''The Broken Heart of America'', Harvard professor Walter Johnson

Walter Perry Johnson (November 6, 1887 – December 10, 1946), nicknamed "Barney" and "The Big Train", was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played his entire 21-year baseball career in Major League Baseball as a right-ha ...

wrote that on many occasions throughout the history of the enslavement of Africans in the US, many instances of genocide occurred, instances which included the separation of men from their wives, effectively reducing the size of the African-American population. For a black American who lived during the era of U.S. slavery, no rights were guaranteed, whether they were personally enslaved or not.

According to author Khalil Gibran Muhammad, the majority of white people who envisioned the coming of a day when black people would be deemed legally equal to white people were abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. When enslaved African Americans were emancipated, many of their white fellow Americans were uncomfortable with the idea of these two races living amongst each other, coexisting in the same nation with the equal rights. Many white Americans began advocating for the colonization of African nations with black Americans.

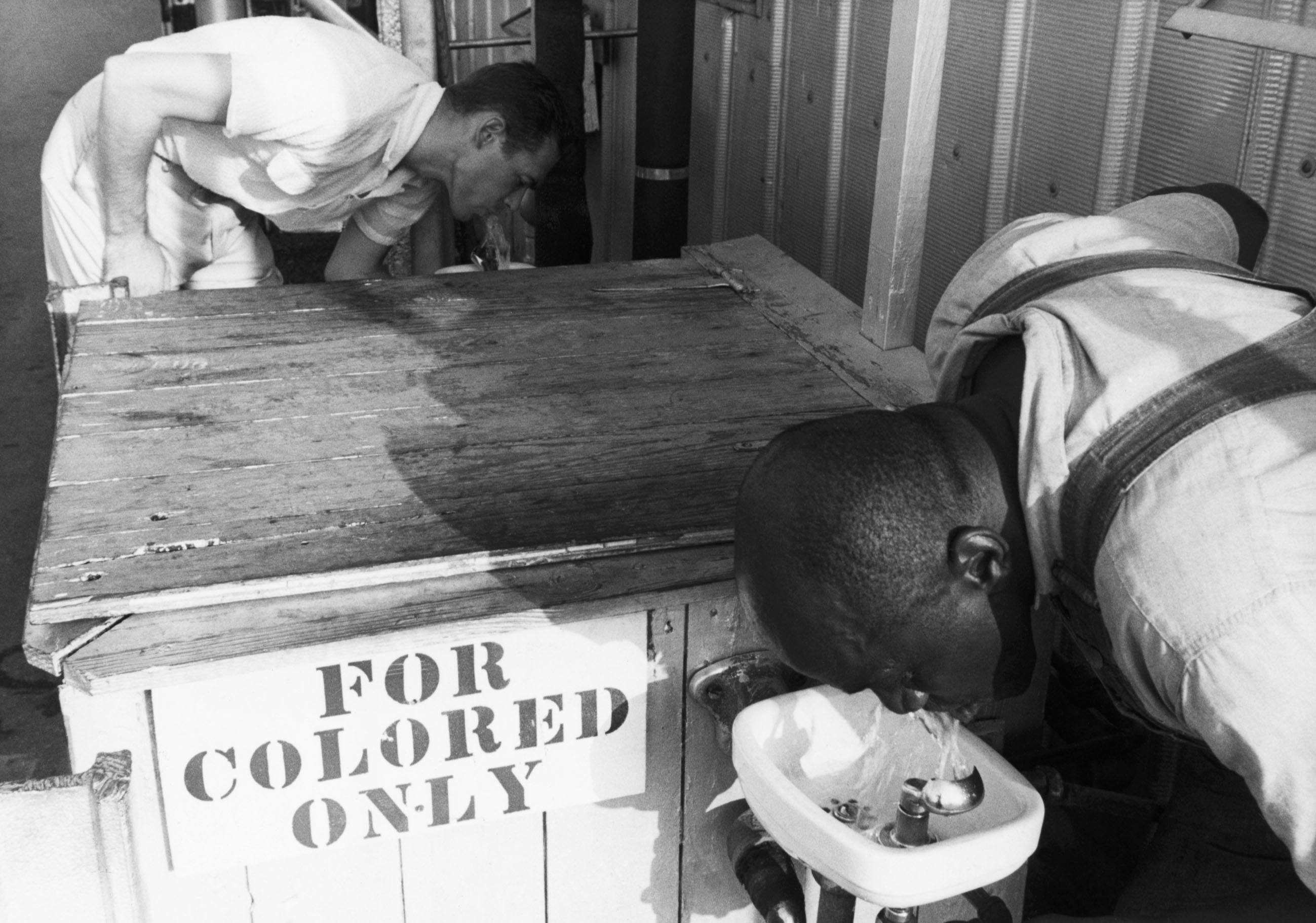

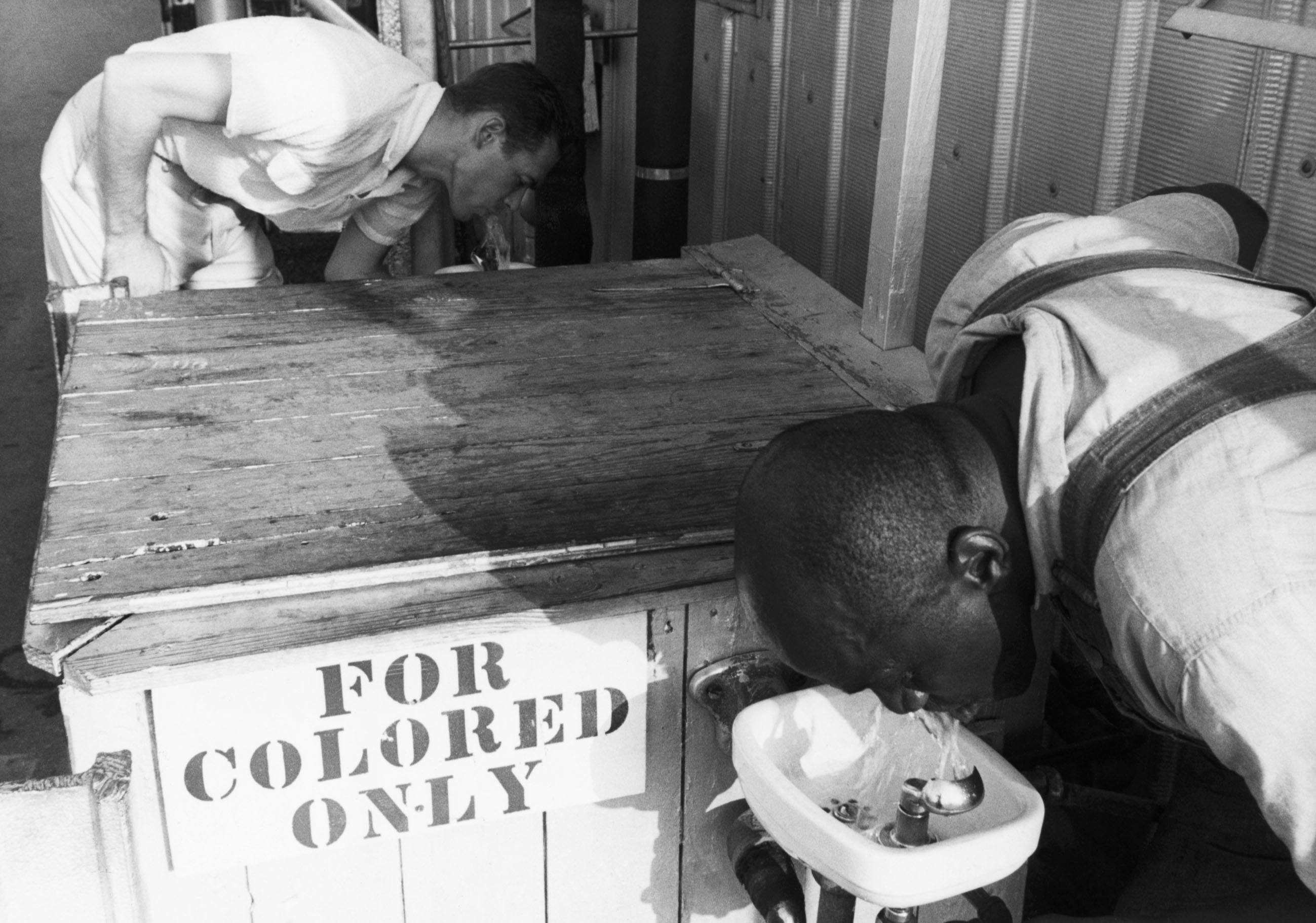

Jim Crow as genocide

Petition to the United Nations

TheUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

(UN) was formed in 1945. The UN debated and adopted a Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

in late 1948, holding that genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

was the " intent to destroy, in whole or in part", a racial group. Based on the "in part" definition, the Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Li ...

(CRC), a group composed of African Americans with Communist affiliations, presented to the UN in 1951 a petition called "We Charge Genocide

''We Charge Genocide'' is a paper accusing the United States government of genocide based on the UN Genocide Convention. This paper was written by the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) and presented to the United Nations at meetings in Paris in Decem ...

." The petition listed 10,000 unjust deaths of African Americans in the nine decades since the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. It described lynching, mistreatment, murder and oppression by whites against blacks, concluding that the US government was refusing to address "the persistent, widespread, institutionalized commission of the crime of genocide". The petition was presented to the UN convention in Paris by CRC leader William L. Patterson, and in New York City by the singer and actor Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplish ...

who was a civil rights activist and a Communist member of CRC.

The Cold War raised American concerns about Communist expansionism. The CRC petition was viewed by the US government as being against America's best interests with regard to fighting Communism. The petition was ignored by the UN; many of the charter countries looked to the US for guidance and were not willing to arm the enemies of the US with more propaganda about its failures in domestic racial policy. American responses to the petition were various: Radio journalist Drew Pearson spoke out against the supposed "Communist propaganda" before it was presented to the UN.

Professor Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer who had helped draft the UN Genocide Convention, said that the CRC petition was a misguided effort which drew attention away from the

The Cold War raised American concerns about Communist expansionism. The CRC petition was viewed by the US government as being against America's best interests with regard to fighting Communism. The petition was ignored by the UN; many of the charter countries looked to the US for guidance and were not willing to arm the enemies of the US with more propaganda about its failures in domestic racial policy. American responses to the petition were various: Radio journalist Drew Pearson spoke out against the supposed "Communist propaganda" before it was presented to the UN.

Professor Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer who had helped draft the UN Genocide Convention, said that the CRC petition was a misguided effort which drew attention away from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

's genocide of Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP) issued a statement saying that there was no black genocide even though serious matters of racial discrimination certainly did exist in America. Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White (July 1, 1893 – March 21, 1955) was an American civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for a quarter of a century, 1929–1955, after joining the organi ...

, leader of the NAACP, wrote that the CRC petition contained "authentic" instances of discrimination, mostly taken from reliable sources. He said, "Whatever the sins of the nation against the Negro—and they are many and gruesome—genocide is not among them." UN Delegate Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

said that it was "ridiculous" to characterize long term discrimination as genocide.

The "We Charge Genocide" petition received more notice in international news than in domestic US media. French and Czech media carried the story prominently, as did newspapers in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. In 1952, African-American author J. Saunders Redding

J. Saunders Redding (October 13, 1906 - March 2, 1988) was a professor and author in the United States. He was the first African American faculty member in the Ivy League.

Early life

Jay Saunders Redding was born October 13, 1906, in Wilmingto ...

traveling in India was repeatedly asked questions about specific instances of civil rights abuse in the US, and the CRC petition was used by Indians to rebut his assertions that US race relations were improving. In the US, the petition faded from public awareness by the late 1950s. In 1964, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

and his Organization of Afro-American Unity, citing the same lynchings and oppression described in the CRC petition, began to prepare their own petition to the UN asserting that the US government was engaging in genocide against black people. The 1964 Malcolm X speech " The Ballot or the Bullet" also draws from "We Charge Genocide".

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and following many years of mistreatment of African Americans by white Americans, the US government's official policies regarding this mistreatment shifted significantly. The American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU) said in 1946 that negative international opinion about US racial policies helped to pressure the US into alleviating the mistreatment of ethnic minorities. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

signed an order desegregating the military, and black citizens increasingly challenged other forms of racial discrimination. In 1948, even if African Americans worked side by side with their white counterparts, they were often segregated into separate neighborhoods due to redlining.

Lynching and other racial killings

Walter Johnson has written that the first lynching to occur in the United States was that of Francis McIntosh, a free man of black and white ancestry. He argued that this lynching ignited a series of them, all with the goal of " ethnic cleansing" and that Abraham Lincoln, who was not yet president, was more concerned by the vigilantism of the lynching than the murder itself. Lincoln referred to McIntosh as "obnoxious" in his 1838 speech later dubbed the Lyceum Address. According to theNational Memorial for Peace and Justice

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, informally known as the National Lynching Memorial, is a national memorial to commemorate the black victims of lynching in the United States. It is intended to focus on and acknowledge past racial ter ...

4,400 black people killed in lynchings and other racial killings between 1877 and 1950.

Brandy Marie Langley argued, "The physical killing of black people in America, at this time period, was consistent with Lemkin's original idea of genocide." Famous literary and social activist figures such as Mark Twain and Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells (full name: Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for ...

were compelled to speak out about lynchings. Twain's essay about lynchings titled "The United States of Lyncherdom "The United States of Lyncherdom" is an essay by Mark Twain written in 1901. He wrote it in response to the mass lynchings in Pierce City, Missouri, of Will Godley, his grandfather French Godley, and Eugene Carter (also known as Barrett). The thre ...

," a remark on widespread occurrence of lynchings in the US. According to Christopher Waldrep, the media and racist whites, both inadvertently and not, exaggerated the presence of black crime as a method of appeasing their own guilt surrounding the lynchings African Americans.

Sterilization

Beginning in 1907, some US state legislatures passed laws allowing for thecompulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

of criminals, mentally retarded people, and institutionalized mentally ill

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

patients. At first, African Americans and white Americans suffered sterilization in roughly equal ratio. By 1945, some 70,000 Americans had been sterilized in these programs. In the 1950s, the federal welfare program Aid to Families with Dependent Children

Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was a federal assistance program in the United States in effect from 1935 to 1997, created by the Social Security Act (SSA) and administered by the United States Department of Health and Human Ser ...

(AFDC) was criticized by some whites who did not want to subsidize poor black families. College course study guide States such as North and South Carolina performed sterilization procedures on low-income black mothers who were giving birth to their second child. The mothers were told that they would have to agree to have their tubes tied or their welfare benefits would be cancelled, along with the benefits of the families they were born into. Because of such policies, especially prevalent in Southern states, sterilization of African Americans in North Carolina increased from 23% of the total in the 1930s and 1940s to 59% at the end of the 1950s, and rose further to 64% in the mid-1960s.

In mid-1973 news stories revealed the forced sterilization of poor black women and children, paid for by federal funds. Two girls of the Relf family in Mississippi, deemed mentally incompetent at ages 12 and 14, and also 18-year-old welfare recipient Nial Ruth Cox of North Carolina, were prominent cases of involuntary sterilization. ''Jet'' magazine presented the story under the headline "Genocide". Critics said these stories were publicized by activists against legal abortion. According to Gregory Price, government policies led to higher rates of sterilization amongst black Americans than white on the basis of racist beliefs. He writes that in the early 1900s, the goal of eugenicists was to create a biologically fit population, but and that these standards of biological fitness deliberately excluded black people, who were claimed to not be capable of making legitimate contributions to the national economy.

Systemic racism as genocide

We Charge Genocide

''We Charge Genocide'' is a paper accusing the United States government of genocide based on the UN Genocide Convention. This paper was written by the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) and presented to the United Nations at meetings in Paris in Decem ...

estimated 30,000 more black people died each year due to various racist policies and that black people had an 8-year shorter life span than white Americans. In this vein, Historian Matthew White estimates that 3.3 million more non-white people died from 1900 up to the 1960s than they would have if they had died at the same rate as white people.

War's effects on black communities

African Americans pushed for equal participation in US military service in the first part of the 20th century and especially during World War II. Finally, PresidentHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

signed legislation to integrate the US military in 1948. However, Selective Service System deferments, military assignments, and especially the recruits accepted through Project 100,000

Project 100,000, also known as McNamara's 100,000, McNamara's Folly, McNamara's Morons, and McNamara's Misfits, was a controversial 1960s program by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) to recruit soldiers who would previously have been ...

resulted in a greater representation of blacks in combat in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

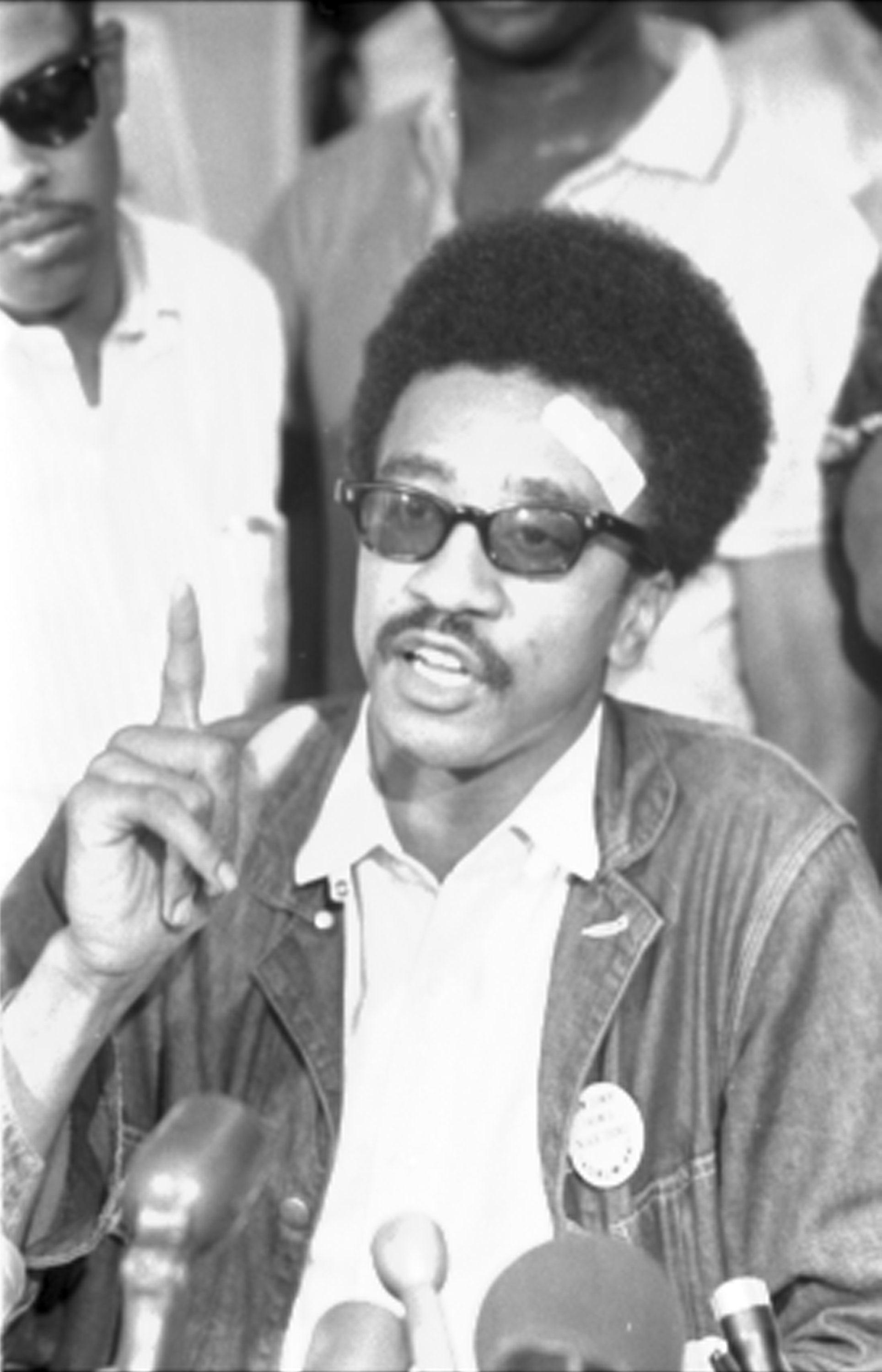

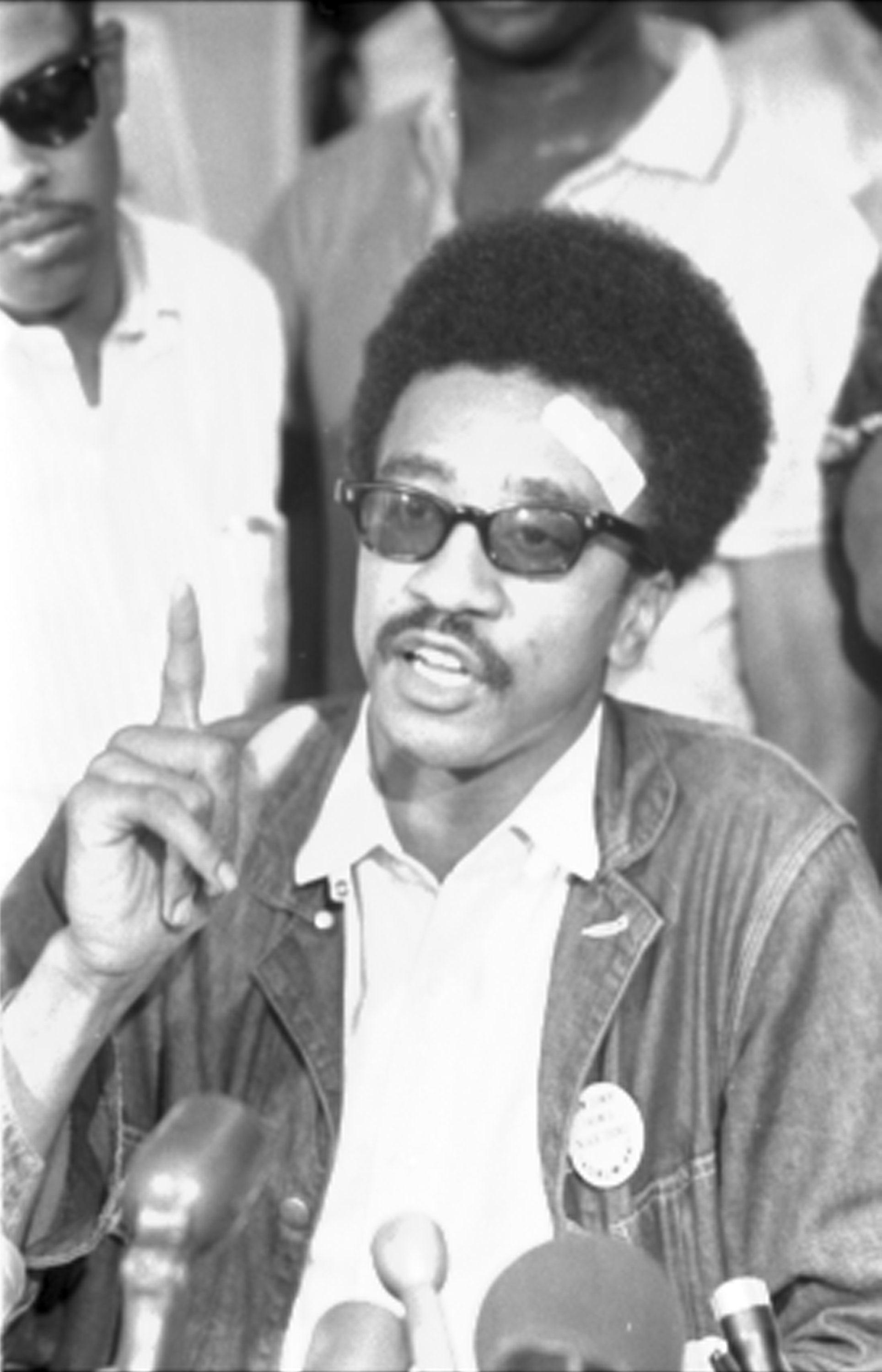

in the second half of the 1960s. African Americans represented 11% of the US population but 12.6% of troops sent to Vietnam. Cleveland Sellers

Cleveland “Cleve” Sellers Jr. (born November 8, 1944) is an American educator and civil rights activist.

During the Civil Rights Movement, Sellers helped lead the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was the only person convicted an ...

said that the drafting of poor black men into war was "a plan to commit calculated genocide". Former SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

, black congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (November 29, 1908 – April 4, 1972) was an American Baptist pastor and politician who represented the Harlem neighborhood of New York City in the United States House of Representatives from 1945 until 1971. He was t ...

and SNCC member Rap Brown agreed. In October 1969, King's widow Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was married to Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she ...

spoke at an anti-war protest held at the primarily black Morgan State College

Morgan State University (Morgan State or MSU) is a public historically black research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It is the largest of Maryland's historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). In 1867, the university, then known a ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. Campus leaders published a statement against what they termed "black genocide" in Vietnam, blaming President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

in the US as well as President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

Nguyễn Văn Thiệu (; 5 April 1923 – 29 September 2001) was a South Vietnamese military officer and politician who was the president of South Vietnam from 1967 to 1975. He was a general in the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF), becam ...

and Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ

Nguyễn Cao Kỳ (; 8 September 1930 – 23 July 2011) was a South Vietnamese military officer and politician who served as the chief of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force in the 1960s, before leading the nation as the prime minister of South V ...

from South Vietnam.

Author James Forman Jr.

James Forman Jr. (born James Robert Lumumba Forman; June 22, 1967) is an American legal scholar currently serving as the Professor of Law at Yale Law School. He is the author of '' Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America'', which ...

has called the War on Drugs

The war on drugs is a global campaign, led by the United States federal government, of drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the United States.Cockburn and St. Clair, 1 ...

"a misstep hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

is so damaging that future generations are left shaking their heads in disbelief." According to Forman, the war on drugs has had widespread effects, including an increased punitory criminal justice system that disproportionately affected Black Americans, especially those in low-income neighborhoods. Forman further writes that one consequence is that, even though black and white people have similar rates of drug use, black people are more likely to be punished for it by the judicial system.

Elizabeth Hinton writes that two other "wars" that have had detrimental effects on the black community - the War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national ...

and War on Crime. According to Hinton black men are imprisoned at a rate of 1 in 11. This topic is also explored in Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander (born October 7, 1967) is an American writer and civil rights activist. She is best known for her 2010 book '' The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness''. Since 2018, she has been an opinion columnist ...

's The New Jim Crow. Alexander argues that, despite many Americans wanting to believe that the election of President Obama ushered in a new age where race no longer mattered, or at least not as much, America is still deeply affected by its racial history. Alexander writes that there has been a "systemic breakdown of black and poor communities devastated by mass unemployment, social neglect, economic abandonment, and intense police surveillance." President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, stated in a commencement speech delivered at Howard University that there is a stark contrast between black and white poverty. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

__NOTOC__

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor is an American academic, writer, and activist. She is a professor of African American Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of ''From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation'' (2016). For this book, ...

writes that the contrast is a result of systemic injustices carried out over the course of centuries against the black community.

Prison

In 1969, H. Rap Brown wrote in his autobiography, '' Die Nigger Die!'', that American courts "conspire to commit genocide" against blacks by putting a disproportionate number of them in prison. Political scientist Joy A. James wrote that "antiblack genocide" is the motivating force which explains the way that US prisons are filled largely with black prisoners. Author and former prisoner Mansfield B. Frazier contends that the rumor in American ghettos "that whites are secretly engaged in a program of genocide against the black race" is given "a measure of validity" by the number of "black men of child-producing age who are imprisoned for crimes for which men of other races are not. The book New Directions for Youth Development describes theschool-to-prison pipeline

In the United States, the school-to-prison pipeline (SPP), also known as the school-to-prison link, school–prison nexus, or schoolhouse-to-jailhouse track, is the disproportionate tendency of minors and young adults from disadvantaged backgroun ...

along with ways to end it. It states that "The public school system in the United States, like the country as a whole, is plagued by vast inequalities—that all too frequently are defined along lines of race and class." Over time, as schools have become harsher in enforcing their policies and disciplining students, the criminal justice system has also become harsher in dealing with children. The book states that "Since 1992, fortyfive states have passed laws making it easier to try juveniles as adults, and thirty-one have stiffened sanctions against youths for a variety of offenses".

The way in which certain drugs are criminalized also factors into the large disparities in involvement in the prison system between black and white communities. For instance "conviction for crack selling (more heavily sold and used by people of color) esultsin a sentence 100 times more severe than for selling the same amount of powder cocaine (more heavily sold and used by whites)."

Conspiracy theories

Birth control

Some observers have identified a falling birth rate as a situation which is harmful to arace

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

of people; for instance, in 1905, Teddy Roosevelt said that it was "race suicide" for white Americans if educated white women continued to have fewer children. Certain African-American leaders also taught that political power came with greater population. In 1934, Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

and his Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-Africa ...

resolved that birth control constituted black genocide.

The combined oral contraceptive pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. The pill contains two important hormones: proges ...

, popularly known as "the Pill", was approved for sale as a medicine in US markets in 1957, and in 1961, the use of it for birth control was also approved. In 1962, civil rights activist Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban ...

told the National Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

not to support birth control for blacks. Marvin Davies, leader of the Florida chapter of the NAACP, said that black women should reject birth control and produce more babies so that black political influence would increase in the future.

Ideas of reproductive fitness were still at the center of American family planning in the 1960s. Physicians preferred to prescribe the Pill to white middle-class women and the IUD to poor women, especially poor women of color, because the IUD granted them greater control over "unfit" women's behavior. Guttmacher viewed the IUD as an effective method of contraception for individuals in "underdeveloped areas where two things are lacking: one, money and the other sustained motivation.

Once the method was approved for use in the United States, the majority of Pill users were white and middle class women. In part, this trend reflects doctors' preference to prescribe the Pill to members of this population, and it also reflects the cost of the drug. Until the late 1960s, the Pill was prohibitively expensive for working-class and poor women.

After President

Ideas of reproductive fitness were still at the center of American family planning in the 1960s. Physicians preferred to prescribe the Pill to white middle-class women and the IUD to poor women, especially poor women of color, because the IUD granted them greater control over "unfit" women's behavior. Guttmacher viewed the IUD as an effective method of contraception for individuals in "underdeveloped areas where two things are lacking: one, money and the other sustained motivation.

Once the method was approved for use in the United States, the majority of Pill users were white and middle class women. In part, this trend reflects doctors' preference to prescribe the Pill to members of this population, and it also reflects the cost of the drug. Until the late 1960s, the Pill was prohibitively expensive for working-class and poor women.

After President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

passed legislation for government funding of birth control as a part of his War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national ...

in 1964, Black militants became more concerned about a possible government-sponsored black genocide. Cecil B. Moore, head of the NAACP chapter in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, spoke out against a Planned Parenthood effort to establish a stronger presence in northern Philadelphia; the population in the targeted neighborhoods was 70% black. Moore said that it would be "race suicide" if blacks embraced birth control.

From 1965 to 1970, black militant males, especially younger men from poverty-stricken areas, spoke out against birth control by denouncing it as part of a plot to commit a genocide against black people. The Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam were the strongest critics of birth control. The Black Panther Party identified a number of injustices as factors which contributed to black genocide, including social ills that were more serious in black populations than they were in white populations, such as drug abuse, prostitution and

From 1965 to 1970, black militant males, especially younger men from poverty-stricken areas, spoke out against birth control by denouncing it as part of a plot to commit a genocide against black people. The Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam were the strongest critics of birth control. The Black Panther Party identified a number of injustices as factors which contributed to black genocide, including social ills that were more serious in black populations than they were in white populations, such as drug abuse, prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral ...

. Other injustices included unsafe housing, malnutrition and the over-representation of young black men on the front lines of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

. Influential black activists such as singer/author Julius Lester

Julius Bernard Lester (January 27, 1939 – January 18, 2018) was an American writer of books for children and adults and an academic who taught for 32 years (1971–2003) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Lester was also a civil right ...

and comedian Dick Gregory

Richard Claxton Gregory (October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017) was an American comedian, civil rights leader, business owner and entrepreneur, and vegetarian activist. His writings were best sellers. Gregory became popular among the Afric ...

said that blacks should increase the size of their population by avoiding genocidal family planning measures. H. Rap Brown of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) held the view that black genocide consisted of four elements: more blacks executed than whites, malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is "a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients" which adversely affects the body's tissues ...

in impoverished areas affected blacks more than it affected whites, the Vietnam War killed more blacks than whites, and birth control programs in black neighborhoods were trying to end the black race. A birth control clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, was torched by black militants who said it contributed to black genocide.

Black Muslims said that birth control was against the teachings of the Koran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, because in Muslim societies, the primary role of women is the production of children. In this context, the black Muslims believed that birth control was part of a genocidal attack which was being launched against them by whites. The Muslim weekly journal, '' Muhammad Speaks'', contained many articles which demonized

Demonization or demonisation is the reinterpretation of polytheistic deities as evil, lying demons by other religions, generally by the monotheistic and henotheistic ones. The term has since been expanded to refer to any characterization of indivi ...

birth control.

In Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the seat of Essex County and the second largest city within the New York metropolitan area.Black Power movement held its first convention: the National Conference on Black Power. The convention identified several means by which whites were attempting to annihilate blacks. Injustices in housing practices, reductions in  Black women were generally critical of the Black Power Movement's rejection of birth control. In 1968, a group of black radical feminists in Mt. Vernon, New York issued "The Sisters Reply"; a rebuttal which said that birth control gave black women the "freedom to fight the genocide of black women and children," referring to the greater death rate among children and mothers in poor families. Frances M. Beal, co-founder of the Black Women's Liberation Committee of the SNCC, refused to believe that the black woman must be subservient to the black man's wishes.

Black women were generally critical of the Black Power Movement's rejection of birth control. In 1968, a group of black radical feminists in Mt. Vernon, New York issued "The Sisters Reply"; a rebuttal which said that birth control gave black women the "freedom to fight the genocide of black women and children," referring to the greater death rate among children and mothers in poor families. Frances M. Beal, co-founder of the Black Women's Liberation Committee of the SNCC, refused to believe that the black woman must be subservient to the black man's wishes.

p. 51

/ref> However, this folk knowledge was suppressed in the new American culture, especially by the nascent After the January 1973 ''

After the January 1973 ''

welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

benefits, and government-subsidized family planning were all identified as elements of "black genocide". ''Ebony'' magazine printed a story in March 1968 which revealed that black genocide was believed by poor blacks to be the impetus behind government-funded birth control.

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, was a strong proponent of birth control for blacks. In 1966, he won the Margaret Sanger Award in Human Rights, an award which honors the tireless birth control activism of Margaret Sanger, a co-founder of Planned Parenthood. King emphasized the fact that birth control gave the black man better command of his personal economic situation, keeping the number of his children within his monetary means. In April 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., was shot and killed. In 1971, Charles V. Willie

Charles Vert Willie (October 8, 1927 – January 11, 2022) was an American sociologist who was the Charles William Eliot Professor of Education, Emeritus at Harvard University. His areas of research included desegregation, higher education, publi ...

wrote that among African Americans, this event marked the beginning of serious reflection "about the possibility of lack

Lack may refer to:

Places

* Lack, County Fermanagh, a townland in Northern Ireland

* Lack, Poland

* Łąck, Poland

* Lack Township, Juniata County, Pennsylvania, US

Other uses

* Lack (surname)

* Lack (manque), a term in Lacan's psychoanalyti ...

genocide in America. There were lynchings, murders, and manslaughters in the past. But the assassination of Dr. King was too much. Many blacks believed that Dr. King had represented their best... If America could not accept Dr. King, then many felt that no black person in America was safe."

Black women were generally critical of the Black Power Movement's rejection of birth control. In 1968, a group of black radical feminists in Mt. Vernon, New York issued "The Sisters Reply"; a rebuttal which said that birth control gave black women the "freedom to fight the genocide of black women and children," referring to the greater death rate among children and mothers in poor families. Frances M. Beal, co-founder of the Black Women's Liberation Committee of the SNCC, refused to believe that the black woman must be subservient to the black man's wishes.

Black women were generally critical of the Black Power Movement's rejection of birth control. In 1968, a group of black radical feminists in Mt. Vernon, New York issued "The Sisters Reply"; a rebuttal which said that birth control gave black women the "freedom to fight the genocide of black women and children," referring to the greater death rate among children and mothers in poor families. Frances M. Beal, co-founder of the Black Women's Liberation Committee of the SNCC, refused to believe that the black woman must be subservient to the black man's wishes. Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, philosopher, academic, scholar, and author. She is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. A feminist and a Marxist, Davis was a longtime member of ...

and Linda LaRue denounced the limitations which male Black Power activists imposed upon female Black Power activists, limitations which directed them to serve as mothers by producing "warriors for the revolution." Toni Cade said that indiscriminate births would not bring the liberation of blacks closer to realization; she advocated the use of the Pill as a tool to help black women space out the births of black children, to make it easier for families to raise them. The Black Women's Liberation Group accused "poor black men" of failing to support the babies which they helped produce, therefore supplying young black women with a reason to use contraceptives. Dara Abubakari, a black separatist, wrote that "women should be free to decide if and when they want children". A 1970 study found that 80% of black women in Chicago approved of birth control, and it also found that 75% of women were using it during their child-bearing years. A 1971 study found that a majority of black men and women were in favor of government-subsidized birth control.

In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, a community struggle both for and against the establishment of a birth control clinic in the Homewood area of east Pittsburgh made national news. Women in Pittsburgh had lobbied for the establishment of a birth control clinic in the 1920s and they were relieved when the American Birth Control League

The American Birth Control League (ABCL) was founded by Margaret Sanger in 1921 at the First American Birth Control Conference in New York City. The organization promoted the founding of birth control clinics and encouraged women to control thei ...

(ABCL) established one in 1931. The ABCL changed its name to Planned Parenthood in 1942. The Pittsburgh clinic initiated an educational outreach program to poor families in the Lower Hill District in 1956. This program was twinned into the poverty-stricken Homewood-Brushton area in 1958. Planned Parenthood considered opening another clinic there, and it conducted meetings with community leaders. In 1963 a mobile clinic was moved around the area. In December 1965, the Planned Parenthood Clinic of Pittsburgh (PPCP) applied for federal funding based on the War on Poverty legislation which Johnson had promoted. In May 1966, the application was approved, and the PPCP began to establish clinics throughout Pittsburgh, a total of 18 clinics were established throughout Pittsburgh by 1967, 11 of these clinics were placed in poor districts and they were also subsidized by the federal government. In mid-1966, the Pennsylvania state legislature held family planning funds up in committee. Catholic bishops gained media exposure for asserting that Pittsburgh's birth control efforts were a form of covert black genocide. In November 1966, the bishops said that the government was coercing poor people to have smaller families. Some black leaders such as local NAACP member Dr. Charles Greenlee supported the bishops' assertion that birth control was black genocide. Greenlee said that Planned Parenthood was "an honorable and good organization" but he also said that the federal Office of Economic Opportunity

The Office of Economic Opportunity was the agency responsible for administering most of the War on Poverty programs created as part of United States President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society legislative agenda. It was established in 1964 as an ...

was sponsoring genocidal programs. Greenlee said that "the Negro's birth rate is the only weapon he has. When he reaches 21 he can vote." Greenlee targeted the Homewood clinic for closure; in doing so, he allied himself with black militant William "Bouie" Haden and Catholic prelate Charles Owen Rice

Monsignor Charles Owen Rice (November 21, 1908 – November 13, 2005) was a Catholic priest and an American labor activist.

Background

He was born in Brooklyn, New York to Irish immigrants. His mother died when he was four, and he and his ...

in order to speak out against black genocide, and he also spoke out against the PPCP's educational outreach program. Planned Parenthood's Director of Community Relations Dr. Douglas Stewart said that the false charge of black genocide was harming the national advancement of blacks. In July 1968, Haden announced that he was willing to blow up the clinic in order to prevent it from operating. The Catholic church paid him a $10,000 salary, igniting an outcry in Pittsburgh's media. Bishop John Wright was called a "puppet of Bouie Haden". The PPCP closed the Homewood clinic in July 1968 and it also ended its educational program because it was concerned about violence. The black congregation of the Bethesda United Presbyterian Church issued a statement in which it said that accusations of black genocide were "patently false". A meeting to discuss the issue was scheduled for March 1969. About 200 women, mostly black, appeared in support of the clinic, and it was reopened. This event was seen as a major defeat for the black militant notion that government-funded birth control was black genocide.

Other prominent black advocates for birth control included Carl Rowan, James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

, Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

, Jerome H. Holland

Jerome Heartwell "Brud" Holland (January 9, 1916 – January 13, 1985) was an American university president and diplomat. He was the first African American to play football at Cornell University, and was chosen as an All American in 1937 and 1938 ...

, Ron Dellums and Barbara Jordan

Barbara Charline Jordan (February 21, 1936 – January 17, 1996) was an American lawyer, educator, and politician. A Democrat, she was the first African American elected to the Texas Senate after Reconstruction and the first Southern African-A ...

.

In the US in the 21st century, black women are most likely to be at risk for unintended pregnancies: 84% of black women of reproductive age use birth control, in contrast to 91% of Caucasian and Hispanic women, and 92% of Asian American women. This situation results in black women having the highest rate of unintended pregnancies—in 2001, almost 10% of black women who gave birth between the ages of 15 and 44 had unintended pregnancies, which was more than twice the rate of unintended pregnancies among white women. Poverty contributes to these statistics, because low-income women are more likely to experience disruptions in their lives; disruptions which affect the steady use of birth control. People who live in poor areas are more suspicious of the health care system, and as a result, they may reject medical treatment and advice, especially, they may reject less-critical wellness treatments such as birth control.

Abortion

Slave women brought with them from Africa the knowledge of traditional folk birth control practices, and of abortion obtained through the use of herbs, blunt trauma, and other methods of killing the fetus or producing strong uterine cramps. Slave women were often expected to breed more slave children to enrich their owners, but some quietly rebelled. In 1856 a white doctor reported that a number of slave owners were upset that their slaves appeared to hold a "secret by which they destroy the foetus at an early age of gestation".Silliman 2004p. 51

/ref> However, this folk knowledge was suppressed in the new American culture, especially by the nascent

American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's sta ...

, and its practice fell away.

After slavery ended, black women formed social groups and clubs in the 1890s to "uplift their race." The revolutionary idea that a black woman might enjoy a full life without ever being a mother was presented in Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin's magazine ''The Woman's Era

''The Woman's Era'' was the first national newspaper published by and for black women in the United States. Originally established as a monthly Boston newspaper, it became distributed nationally in 1894 and ran until January 1897, with Josephine ...

''. Knowledge was secretly shared among clubwomen regarding how to find practitioners offering illegal medical or traditional abortion services. Working-class black women, who were more often forced into having sex with white men, continued to have a need for birth control and abortions. Black women who earned less than $10 per day paid $50 to $75 for an illegal and dangerous abortion. Throughout the 20th century, "backstreet" abortion providers in black neighborhoods were also sought out by poor white women who wanted to rid themselves of pregnancies. Abortion providers who were black were prosecuted much more often than white ones were.

During this time the Black Panthers printed pamphlets which described abortion as black genocide, expanding on their earlier stance with regard to family planning. However, most minority groups stood in favor of the decriminalization of abortion; ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reported in 1970 that more non-white women than white women died as a result of "crude, illegal abortions". Legalized abortion was expected to produce fewer deaths of the mother. A poll in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, conducted by the National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

(NOW), found that 75% of blacks supported the decriminalization of abortion.

After the January 1973 ''

After the January 1973 ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and s ...

'' Supreme Court decision made abortion legal in the US, '' Jet'' magazine publisher Robert E. Johnson authored an article titled "Legal Abortion: Is It Genocide Or Blessing In Disguise?" Johnson cast the issue as one which polarized the black community along gender lines: black women generally viewed abortion as a "blessing in disguise" but black men such as Reverend Jesse Jackson viewed it as black genocide. Jackson said he was in favor of birth control but not abortion. The next year, Senator Mark Hatfield, an opponent of legal abortion, emphasized to Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

that Jackson "regards abortion as a form of genocide practiced against blacks."

In ''Jet'', Johnson quoted Lu Palmer, a radio journalist in Chicago, who said that there was inequity between the sexes: a young black man who helped create an unwanted pregnancy could go his "merry way" while the young woman who had been involved in it was stigmatized by society and saddled with a financial and emotional burden, often without a safety net of caregivers to sustain her. Civil rights lawyer Florynce Kennedy

Florynce Rae Kennedy (February 11, 1916 – December 21, 2000) was an American lawyer, radical feminist, civil rights advocate, lecturer and activist.

Early life

Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Missouri, to an African-American family. Her ...

criticized the idea that black women were needed to populate the Black Power revolution. She said that black majorities in the Deep South were not known to be hotbeds of revolution, and that limiting black women to the role of mothers was "not too far removed from a cultural past where black women were encouraged to be breeding machines for their slave masters." In the Tennessee General Assembly in 1967, Dorothy Lavinia Brown

Dorothy Lavinia Brown (January 7, 1914 – June 13, 2004Martini, KelliDorothy Brown, South's first African-American woman doctor, dies News Archives, The United Methodist Church, June 14, 2004, UMC.org), also known as "Dr. D.", was an African-Ame ...

, MD, the first African-American woman surgeon and a state assemblywoman, sponsored a proposed bill to fully legalize abortion. Later Brown, would say black women "should dispense quickly the notion that abortion is genocide." Rather, they should look to the earliest Atlantic slave traders as the root of genocide. Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita Chisholm ( ; ; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. Chisholm represented New York's 12th congressional distr ...

wrote in 1970 that the linking of abortion and genocide "is male rhetoric, for male ears."

However, a link between abortion and black genocide has been claimed by later observers. Mildred Fay Jefferson

Mildred Fay Jefferson (April 6, 1927 – October 15, 2010)

, a surgeon and an activist against legal abortion, wrote about black genocide in 1978, saying "abortionists have done more to get rid of generations and cripple others than all of the years of slavery and lynching." Jefferson's views were shared by Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

state legislator and NAACP member Rosetta A. Ferguson, who led the effort to defeat a Michigan abortion liberalization bill in 1972. Ferguson described abortion as black genocide.

In 2009, American anti-abortion activists

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

revived the idea that a black genocide was in progress. A strong response from this strategy was observed among blacks, and in 2010 more focus was placed on describing abortion as black genocide. White anti-abortion activist Mark Crutcher produced a documentary called '' Maafa 21'' which criticizes Planned Parenthood and its founder Margaret Sanger, and describes various historic aspects of eugenics, birth control and abortion with the aim of convincing the viewer that abortion is black genocide. Anti-abortion activists showed the documentary to black audiences across the US. The film was criticized as propaganda and a false representation of Sanger's work. In March 2011, a series of abortion-as-genocide billboard advertisements were shown in South Chicago

South Chicago, formerly known as Ainsworth, is one of the 77 community areas of Chicago, Illinois.

This chevron-shaped community is one of Chicago's 16 lakefront neighborhoods near the southern rim of Lake Michigan 10 miles south of downtown. ...

, an area with a large population of African Americans. From May to November 2011, presidential candidate Herman Cain criticized Planned Parenthood, calling abortion "planned genocide" and "black genocide".

After Stacey Abrams

Stacey Yvonne Abrams (; born December 9, 1973) is an American politician, lawyer, voting rights activist, and author who served in the Georgia House of Representatives from 2007 to 2017, serving as minority leader from 2011 to 2017. A member ...

lost the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial election

The 2018 Georgia gubernatorial election took place on November 6, 2018, concurrently with other statewide and local elections to elect the next governor of the U.S. state of Georgia. Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp won the election ...

, anti-abortion activist Arthur A. Goldberg wrote that she lost in part because of her stance in favor of abortion rights, which he said ignored "the staggering number of abortions in the black community" which amounted to black genocide. In 2019, ''The New York Times'' wrote that "the abortion debate is inextricably tied to race" in the view of black American communities that are challenged with many other racial disparities which together constitute black genocide.

Analysis

In 1976, sociologistIrving Louis Horowitz Irving Louis Horowitz (September 25, 1929 – March 21, 2012) was an American sociologist, author, and college professor who wrote and lectured extensively in his field, and his later years came to fear that it risked being seized by left-wing ide ...

published an analysis of black genocide in which he concluded that racist vigilantism and sporadic actions by individual whites were to blame for the various statistics which show that the rates of death which blacks experience are higher than the rates of death which whites experience. Horowitz concluded his analysis of black genocide by stating that the US government could not be implicated as a conspirator because there was no conspiracy to engage in a concerted black genocide.

In 2013, political scientist

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

Joy A. James wrote that the "logical conclusion" of American racism

Racism in the United States comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are related to each other, are held by various people and groups in the United States, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and ...

is genocide and members of the black elite are complicit, along with white Americans

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

, in carrying out black genocide.James 2013, pp. 270, 277.

See also

*African-American history

African-American history began with the arrival of Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. Former Spanish slaves who had been freed by Francis Drake arrived aboard the Golden Hind at New Albion in California in 1579. The ...

* African Americans and birth control

African Americans', or Black Americans', access to and use of birth control are central to many social, political, cultural and economic issues in the United States. Birth control policies in place during American slavery and the Jim Crow era pa ...

* Afrophobia

Afrophobia, Afroscepticism, or Anti-African sentiment is a perceived or actual prejudice, hostility, discrimination, or racism towards people and cultures of Africa and the African diaspora.

Prejudice against Africans and people of African desce ...

* Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter (abbreviated BLM) is a decentralized political and social movement that seeks to highlight racism, discrimination, and racial inequality experienced by black people. Its primary concerns are incidents of police br ...

* Black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

* Black power

* Black Power movement

* Black supremacy

* Great Replacement

The Great Replacement (french: links=no, Grand Remplacement), also known as replacement theory or great replacement theory, is a white nationalist far-right conspiracy theoryPT71 disseminated by French author Renaud Camus. The original theor ...

* Harry R. Jackson Jr., the owner of ''The Truth in Black & White'' website

* Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on African-American communities

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed race-based health care disparities in many countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Canada, and Singapore. These disparities are believed to originate from structural racism in th ...

* Kalergi Plan

* List of conspiracy theories

This is a list of conspiracy theories that are notable. Many conspiracy theories relate to clandestine government plans and elaborate murder plots. Conspiracy theories usually deny consensus or cannot be proven using the historical or scienti ...

* Maafa – a word which is derived from a Swahili term for "disaster, terrible occurrence or great tragedy"

* Mass racial violence in the United States

In the broader context of racism against Black Americans and racism in the United States, mass racial violence in the United States consists of ethnic conflicts and race riots, along with such events as:

* Racially based communal conflicts betwe ...

* ''Medical Apartheid

''Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present'' is a 2007 book by Harriet A. Washington. It is a history of medical experimentation on African Americans. From the era of sl ...

'', a book by Harriet A. Washington which describes the history of unethical human experimentation

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and tortu ...

on African Americans

* Nadir of American race relations

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African American history and the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century when racism in the country, especially racism against ...

* Political positions of Herman Cain

* Racism against Black Americans

In the context of racism in the United States, racism against African Americans dates back to the colonial era, and it continues to be a persistent issue in American society in the 21st century.

From the arrival of the first Africans in early ...

* Racism in the United States

Racism in the United States comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are related to each other, are held by various people and groups in the United States, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and ...

* Reparations for slavery

Reparations for slavery is the application of the concept of reparations to victims of slavery and/or their descendants. There are concepts for reparations in legal philosophy and reparations in transitional justice. Reparations can take numer ...

* Reparations for slavery in the United States

Reparations for slavery is the application of the concept of reparations to victims of slavery or their descendants. There are concepts for reparations in legal philosophy and reparations in transitional justice. In the US, reparations for sla ...

* Slavery in the United States