Black Belt (region of Chicago) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to

Although du Sable's settlement was established in the 1780s, African Americans would only become established as a community in the 1840s, with the population reaching 1,000 by 1860. Much of this population consisted of escaped slaves from the Upper South. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, African Americans flowed from the Deep South into Chicago, raising the population from approximately 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 in 1890.

In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state. However, in 1865, the state repealed its " Black Laws" and became the first to ratify the 13th Amendment, partly due to the efforts of

Although du Sable's settlement was established in the 1780s, African Americans would only become established as a community in the 1840s, with the population reaching 1,000 by 1860. Much of this population consisted of escaped slaves from the Upper South. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, African Americans flowed from the Deep South into Chicago, raising the population from approximately 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 in 1890.

In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state. However, in 1865, the state repealed its " Black Laws" and became the first to ratify the 13th Amendment, partly due to the efforts of

As the 20th century began, southern states succeeded in passing new constitutions and laws that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Deprived of the right to vote, they could not sit on juries or run for office. They were subject to discriminatory laws passed by white legislators, including racial segregation of public facilities. Segregated education for black children and other services were consistently underfunded in a poor, agricultural economy. As white-dominated legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to re-establish white supremacy and create more restrictions in public life, violence against blacks increased, with

As the 20th century began, southern states succeeded in passing new constitutions and laws that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Deprived of the right to vote, they could not sit on juries or run for office. They were subject to discriminatory laws passed by white legislators, including racial segregation of public facilities. Segregated education for black children and other services were consistently underfunded in a poor, agricultural economy. As white-dominated legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to re-establish white supremacy and create more restrictions in public life, violence against blacks increased, with

The increasingly large black population in Chicago (40,000 in 1910, and 278,000 in 1940) faced some of the same discrimination as they had in the South. It was hard for many blacks to find jobs and find decent places to live because of the competition for housing among different ethnic groups at a time when the city was expanding in population so dramatically. At the same time that blacks moved from the South in the Great Migration, Chicago had recently received hundreds of thousands of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. The groups competed with each other for working-class wages.

Though other techniques to maintain

The increasingly large black population in Chicago (40,000 in 1910, and 278,000 in 1940) faced some of the same discrimination as they had in the South. It was hard for many blacks to find jobs and find decent places to live because of the competition for housing among different ethnic groups at a time when the city was expanding in population so dramatically. At the same time that blacks moved from the South in the Great Migration, Chicago had recently received hundreds of thousands of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. The groups competed with each other for working-class wages.

Though other techniques to maintain

''The African-American Mosaic'',

With a growing base and strong leadership in machine politics, Blacks began to win elective office in local and state government. The first blacks had been elected to office in Chicago in the late 19th century, decades before the Great Migrations. Chicago elected the first post-Reconstruction African-American member of Congress. He was Republican Oscar Stanton De Priest, in

With a growing base and strong leadership in machine politics, Blacks began to win elective office in local and state government. The first blacks had been elected to office in Chicago in the late 19th century, decades before the Great Migrations. Chicago elected the first post-Reconstruction African-American member of Congress. He was Republican Oscar Stanton De Priest, in

The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-to the present

.

*

*

"Black Belt,"

in ''

Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952

'. (Princeton University Press, 2007: , 2013) * Bowly, Devereaux, Jr. ''The Poorhouse: Subsidized Housing in Chicago, 1895–1976'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 1978). * Branch, Taylor. ''Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1964–1965'' (1998). * Cohen, Adam, and Elizabeth Taylor. ''American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley-his battle for Chicago and the nation'' (2001, ) * Coit, Jonathan S., "'Our Changed Attitude': Armed Defense and the New Negro in the 1919 Chicago Race Riot", ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 11 (April 2012), 225–56. * * Dolinar, Brian (ed.)

''The Negro in Illinois. The WPA Papers''

University of Chicago Press, cloth: 2013, ; paper, : 2015. Produced by a special division of the Illinois Writers' Project, part of the

online

* Frady, Marshall. ''Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson'' (1996) * Fremon, David. ''Chicago Politics Ward by Ward'' (Indiana University Press, 1988). * Garrow, David J. ed. ''Chicago 1966: Open Housing Marches, Summit Negotiations, and Operation Breadbasket'' (1989). * Garb, Margaret

(University of Chicago Press, 2014, ) * Gordon, Rita Werner. "The change in the political alignment of Chicago's Negroes during the New Deal." ''Journal of American History'' 56.3 (1969): 584-603. * Gosnell, Harold F. "The Chicago 'Black belt' as a political battleground." ''American Journal of Sociology'' 39.3 (1933): 329-341. * Gosnell, Harold F. ''Negro Politicians; The Rise of Negro Politics in Chicago'' (University of Chicago Press. 1935)

online

also see

online review

* Green, Adam

(University of Chicago Press, 2009, ) * Grimshaw, William J. ''Bitter Fruit: Black Politics and the Chicago Machine, 1931–1991'' (University of Chicago Press, 1992). * Grossman, James R. ''Land of hope: Chicago, black southerners, and the great migration'' (University of Chicago Press, 1991) * Halpern, Rick. ''Down on the Killing Floor: Black and White Workers in Chicago's Packinghouses, 1904-54'' (University of Illinois Press, 1997). * Helgeson, Jeffrey

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, . * Hirsch, Arnold Richard.

'. (University of Chicago Press, 1998, ) * Kenney, William Howland

''Chicago jazz: A cultural history, 1904-1930''

(Oxford University Press, 1993) * Kimble Jr., Lionel. ''A New Deal for Bronzeville: Housing, Employment, and Civil Rights in Black Chicago, 1935–1955'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, ). xiv, 200 pp. * Kleppner, Paul. ''Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor'' (Northern Illinois University Press, 1985); 1983 election of

online

* McGreevy, John T. ''Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the TwentiethCentury Urban North'' (University of Chicago Press, 1996)

excerpt

* Manning, Christopher

in ''Encyclopedia of Chicago.'' (2007); p. 27. * Philpott, Thomas Lee. ''The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterioration and Middle Class Reform, Chicago, 1880–1930'' (Oxford University Press, 1978). * Pickering, George W. ''Confronting the Color Line: The Broken Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in Chicago'' (University of Georgia Press, 1986). * Pinderhughes, Dianne Marie.

Race and ethnicity in Chicago politics: A reexamination of pluralist theory

' (University of Illinois Press, 1987) * Reed, Christopher. ''The Chicago NAACP and the Rise of the Black Professional Leadership, 1910–1966'' (Indiana University Press, 1997). * Rivlin, Gary. ''Fire on the prairie: Chicago's Harold Washington and the politics of race'' (Holt, 1992, ) * Rocksborough-Smith, Ian. ''Margaret T.G. Burroughs and Black Public History in Cold War Chicago''.

''History of Black oriented radio in Chicago, 1929-1963''

(PhD disst. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1981. * Spear, Allan H

(University of Chicago Press, 1967, ) * Street, Paul. "The 'Best Union Members': Class, Race, Culture, and Black Worker Militancy in Chicago's Stockyards during the 1930s." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' (2000): 18-49

online

* Street, Paul. "The logic and limits of 'plant loyalty': black workers, white labor, and corporate racial paternalism in Chicago's stockyards, 1916-1940." ''Journal of social history'' (1996): 659-68

online

* Tuttle Jr, William M. "Labor conflict and racial violence: The black worker in Chicago, 1894–1919." ''Labor History'' 10.3 (1969): 408–432. * Tuttle, William M. ''Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919'' (1970).

The Negro in Chicago

'. (Chicago; University of Chicago Press, 1922). * Johnson, John H. ''Succeeding Against the Odds: The Autobiography of a Great American Businessman'' (1989) about John H. Johnson.

African-American History Tour for the City of Chicago

a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

African Americans in Chicago

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of African Americans In Chicago

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable (also spelled ''Point de Sable'', ''Point au Sable'', ''Point Sable'', ''Pointe DuSable'', ''Pointe du Sable''; before 1750 – 28 August 1818) is regarded as the first permanent non-Indigenous settler of what would ...

’s trading activities in the 1780s. Du Sable, the city's founder, was Haitian of African and French descent. Fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

and freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

established the city's first black community in the 1840s. By the late 19th century, the first black person had been elected to office.

The Great Migrations

''Great Migrations'' is a seven-episode nature documentary television miniseries that airs on the National Geographic Channel, featuring the great migrations of animals around the globe. The seven-part show is the largest programming event in the ...

from 1910 to 1960 brought hundreds of thousands of africans from the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, where they became an urban population. They created churches, community organizations, businesses, music, and literature. African Americans of all classes built a community on the South Side of Chicago for decades before the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, as well as on the West Side of Chicago. Residing in segregated communities, almost regardless of income, the Black residents of Chicago aimed to create communities where they could survive, sustain themselves, and have the ability to determine for themselves their own course in the History of Chicago

Chicago has played a central role in American economic, cultural and political history. Since the 1850s Chicago has been one of the dominant metropolises in the Midwestern United States, and has been the largest city in the Midwest since the 1 ...

.

The black population in Chicago has been shrinking. Many black Chicagoans have moved to the suburbs or Southern cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston, Birmingham, Memphis, and Jackson.

History

Beginnings

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable was a Haitian of French and African descent. Although du Sable's settlement was established in the 1780s, African Americans would only become established as a community in the 1840s, with the population reaching 1,000 by 1860. Much of this population consisted of escaped slaves from the Upper South. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, African Americans flowed from the Deep South into Chicago, raising the population from approximately 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 in 1890.

In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state. However, in 1865, the state repealed its " Black Laws" and became the first to ratify the 13th Amendment, partly due to the efforts of

Although du Sable's settlement was established in the 1780s, African Americans would only become established as a community in the 1840s, with the population reaching 1,000 by 1860. Much of this population consisted of escaped slaves from the Upper South. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, African Americans flowed from the Deep South into Chicago, raising the population from approximately 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 in 1890.

In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state. However, in 1865, the state repealed its " Black Laws" and became the first to ratify the 13th Amendment, partly due to the efforts of John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and Mary Jones, a prominent and wealthy activist couple.

Especially after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Illinois had some of the most progressive anti-discrimination legislation in the nation. School segregation was first outlawed in 1874, and segregation in public accommodations was first outlawed in 1885. In 1870, Illinois extended voting rights to African-American men for the first time, and in 1871, John Jones, a tailor and Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

station manager who successfully lobbied for the repeal of the state's Black Laws, became the first African-American elected official in the state, serving as a member of the Cook County Commission. By 1879, John W. E. Thomas

John William Edinburgh Thomas ( May 1, 1847 – December 18, 1899) was an American businessman, educator, and Illinois politician. Born into slavery in Alabama, he moved to Chicago after the Civil War, where he became a prominent community leade ...

of Chicago became the first African American elected to the Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 181 ...

, beginning the longest uninterrupted run of African-American representation in any state legislature in U.S. history. After the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 1 ...

, Chicago mayor Joseph Medill

Joseph Medill (April 6, 1823March 16, 1899) was a Canadian-American newspaper editor, publisher, and Republican Party politician. He was co-owner and managing editor of the ''Chicago Tribune'', and he was Mayor of Chicago from after the Great Chi ...

appointed the city's first black fire company of nine men and the first black police officer.

Great Migration

As the 20th century began, southern states succeeded in passing new constitutions and laws that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Deprived of the right to vote, they could not sit on juries or run for office. They were subject to discriminatory laws passed by white legislators, including racial segregation of public facilities. Segregated education for black children and other services were consistently underfunded in a poor, agricultural economy. As white-dominated legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to re-establish white supremacy and create more restrictions in public life, violence against blacks increased, with

As the 20th century began, southern states succeeded in passing new constitutions and laws that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Deprived of the right to vote, they could not sit on juries or run for office. They were subject to discriminatory laws passed by white legislators, including racial segregation of public facilities. Segregated education for black children and other services were consistently underfunded in a poor, agricultural economy. As white-dominated legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to re-establish white supremacy and create more restrictions in public life, violence against blacks increased, with lynchings

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

used as extrajudicial enforcement. In addition, the boll weevil

The boll weevil (''Anthonomus grandis'') is a beetle that feeds on cotton buds and flowers. Thought to be native to Central Mexico, it migrated into the United States from Mexico in the late 19th century and had infested all U.S. cotton-growin ...

infestation ruined much of the cotton industry. Voting with their feet, blacks started migrating out of the South to the North, where they could live more freely, get their children educated, and get new jobs.

Industry buildup for World War I pulled thousands of workers to the North, as did the rapid expansion of railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, and the meatpacking

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is gener ...

and steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

industries. Between 1915 and 1960, hundreds of thousands of black southerners migrated to Chicago to escape violence and segregation, and to seek economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the l ...

. They went from being a mostly rural population to one that was mostly urban. "The migration of African Americans from the rural south to the urban north became a mass movement."Allen H. Spear, ''Black Chicago: The Making of a Negro Ghetto (1890–1920)''. The Great Migration radically transformed Chicago, both politically and culturally.

From 1910 to 1940, most African Americans who migrated north were from rural areas. They had been chiefly sharecroppers and laborers, although some were landowners pushed out by the boll weevil disaster. After years of underfunding of public education for blacks in the South, they tended to be poorly educated, with relatively low skills to apply to urban jobs. Like the European rural immigrants, they had to rapidly adapt to a different urban culture. Many took advantage of better schooling in Chicago and their children learned quickly. After 1940, when the second larger wave of migration started, black migrants tended to be already urbanized, from southern cities and towns. They were the most ambitious, better educated with more urban skills to apply in their new homes.

The masses of new migrants arriving in the cities captured public attention. At one point in the 1940s, 3,000 African Americans were arriving every week in Chicago—stepping off the trains from the South and making their ways to neighborhoods they had learned about from friends and the ''Chicago Defender

''The Chicago Defender'' is a Chicago-based online African-American newspaper. It was founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott and was once considered the "most important" newspaper of its kind. Abbott's newspaper reported and campaigned against J ...

''. The Great Migration was charted and evaluated. Urban white northerners started to get worried, as their neighborhoods rapidly changed. At the same time, recent and older ethnic immigrants competed for jobs and housing with the new arrivals, especially on the South Side, where the steel and meatpacking industries had the most numerous working-class jobs.

With Chicago's industries steadily expanding, opportunities opened up for new migrants, including Southerners, to find work. The railroad and meatpacking industries recruited black workers. Chicago's African-American newspaper, the ''Chicago Defender'', made the city well known to southerners. It sent bundles of papers south on the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also c ...

trains, and African-American Pullman Porters

Pullman porters were men hired to work for the railroads as porters on sleeping cars. Starting shortly after the American Civil War, George Pullman sought out former slaves to work on his sleeper cars. Their job was to carry passengers’ ba ...

would drop them off in Black towns. "Chicago was the most accessible northern city for African Americans in Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas." They took the trains north. "Then between 1916 and 1919, 50,000 blacks came to crowd into the burgeoning black belt, to make new demands upon the institutional structure of the South Side."1919 race riot

TheChicago race riot of 1919

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a violent racial conflict between white Americans and black Americans that began on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. During the riot, 38 people died (23 black a ...

was a violent racial conflict started by white Americans against black Americans that began on the South Side on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. During the riot, 38 people died (23 black and 15 white). Over the week, injuries attributed to the episodic confrontations stood at 537, with two thirds of the injured being black and one third white, and approximately 1,000 to 2,000, most of whom were black, lost their homes. Due to its sustained violence and widespread economic impact, it is considered the worst of the scores of riots and civil disturbances across the nation during the "Red Summer" of 1919, so named because of the racial and labor violence and fatalities.

Segregation

The increasingly large black population in Chicago (40,000 in 1910, and 278,000 in 1940) faced some of the same discrimination as they had in the South. It was hard for many blacks to find jobs and find decent places to live because of the competition for housing among different ethnic groups at a time when the city was expanding in population so dramatically. At the same time that blacks moved from the South in the Great Migration, Chicago had recently received hundreds of thousands of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. The groups competed with each other for working-class wages.

Though other techniques to maintain

The increasingly large black population in Chicago (40,000 in 1910, and 278,000 in 1940) faced some of the same discrimination as they had in the South. It was hard for many blacks to find jobs and find decent places to live because of the competition for housing among different ethnic groups at a time when the city was expanding in population so dramatically. At the same time that blacks moved from the South in the Great Migration, Chicago had recently received hundreds of thousands of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. The groups competed with each other for working-class wages.

Though other techniques to maintain housing segregation

Housing segregation in the United States is the practice of denying African Americans and other minority groups equal access to housing through the process of misinformation, denial of realty and financing services, and racial steering. Housing ...

had been used, such as redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services ( financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have sign ...

and exclusive zoning to single-family housing, by 1927 the political leaders of Chicago began to adopt racially restrictive covenants. The Chicago Real Estate Board promoted a racially restrictive covenant to YMCAs, churches, women's clubs, PTAs, Kiwanis clubs, chambers of commerce and property owners' associations. At one point, as much as 80% of the city's area was included under restrictive covenants.

The Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

in '' Shelley v. Kraemer'' ruled in 1948 that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional, but this did not quickly solve blacks' problems with finding adequate housing. Homeowners' associations discouraged members from selling to black families, thus maintaining residential segregation. European immigrants and their descendants competed with African Americans for limited affordable housing, and those who didn't get the house lived on the streets.

In a succession common to most cities, many middle and upper-class whites were the first to move out of the city to new housing, aided by new commuter rail lines and the construction of new highway systems. Later arrivals, ethnic whites and African-American families occupied the older housing behind them. The white residents who had been in the city longest were the ones most likely to move to the newer, most expensive housing, as they could afford it. After 1945, the early white residents (many Irish immigrants and their descendants) on the South Side began to move away under pressure of new migrants and with newly expanding housing opportunities. African Americans continued to move into the area, which had become the black capital of the country. The South Side became predominantly black, and the Black Belt was solidified.

Social and economic conditions

Housing

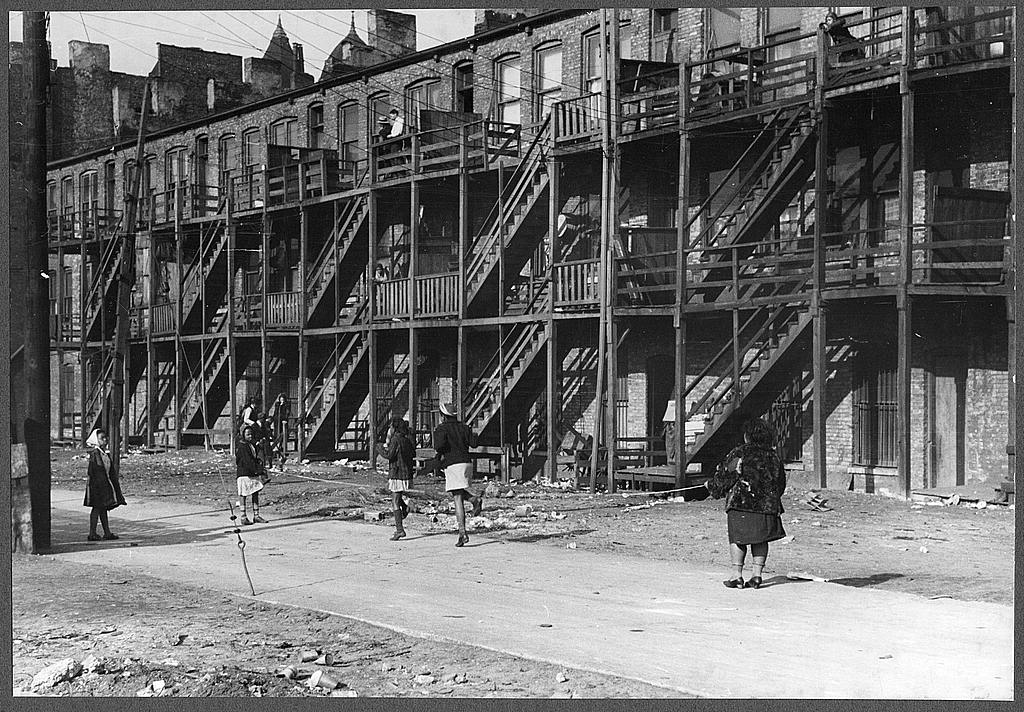

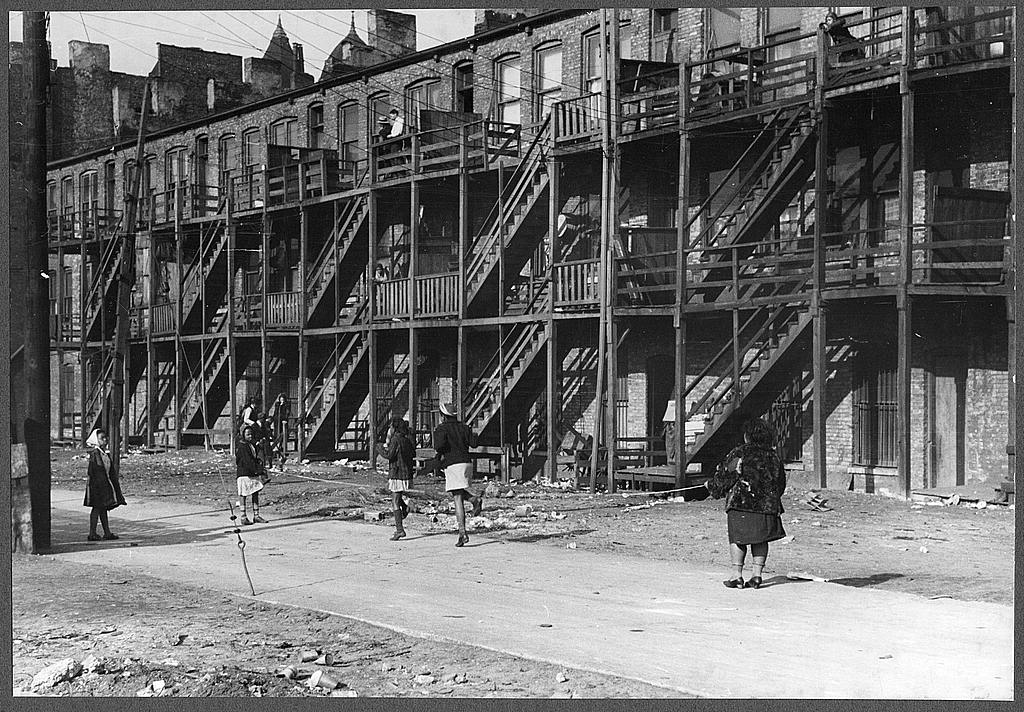

Between 1900 and 1910, the African-American population rose rapidly in Chicago. White hostility and population growth combined to create the ghetto on the South Side. Nearby were areas dominated by ethnic Irish, who were especially territorial in defending against incursions into their areas by any other groups. Most of this large population was composed of migrants. In 1910 more than 75 percent of blacks lived in predominantly black sections of the city. The eight or nine neighborhoods that had been set as areas of black settlement in 1900 remained the core of the Chicago African-American community. The Black Belt slowly expanded as African Americans, despite facing violence and restrictive covenants, pushed forward into new neighborhoods. As the population grew, African Americans became more confined to a delineated area, instead of spreading throughout the city. When blacks moved into mixed neighborhoods, ethnic white hostility grew. After fighting over the area, often whites left the area to be dominated by blacks. This is one of the reasons the black belt region started. The Black Belt of Chicago was the chain of neighborhoods on the South Side ofChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

where three-quarters of the city's African-American population lived by the mid-20th century. In the early 1940s whites within residential blocks formed "restrictive covenants" that served as legal contracts restricting individual owners from renting or selling to black people. The contracts limited the housing available to black tenants, leading to the accumulation of black residents within The Black Belt, one of the few neighborhoods open to black tenants. The Black Belt was an area that stretched 30 blocks along State Street on the South Side and was rarely more than seven blocks wide. With such a large population within this confined area, overcrowding often led to numerous families living in old and dilapidated buildings. The South Side's "black belt" also contained zones related to economic status. The poorest residents lived in the northernmost, oldest section of the black belt, while the elite resided in the southernmost section."Chicago: Destination for the Great Migration"''The African-American Mosaic'',

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

. In the mid-20th century, as African Americans across the United States struggled against the economic confines created by segregation, black residents within the Black Belt sought to create more economic opportunity in their community through the encouragement of local black businesses and entrepreneurs. During this time, Chicago was the capital of Black America. Many African Americans who moved to the Black Belt area of Chicago were from the Southeastern region of the United States.

Immigration to Chicago was another pressure of overcrowding, as primarily lower-class newcomers from rural Europe also sought cheap housing and working class jobs. More and more people tried to fit into converted "kitchenette

A kitchenette is a small cooking area, which usually has a refrigerator and a microwave, but may have other appliances. In some motel and hotel rooms, small apartments, college dormitories, or office buildings, a kitchenette consists of a small re ...

" and basement apartments. Living conditions in the Black Belt resembled conditions in the West Side ghetto or in the stockyards district. Although there were decent homes in the Negro sections, the core of the Black Belt was a slum. A 1934 census estimated that black households contained 6.8 people on average, whereas white households contained 4.7. Many blacks lived in apartments that lacked plumbing, with only one bathroom for each floor. With the buildings so overcrowded, building inspections and garbage collection were below the minimum mandatory requirements for healthy sanitation. This unhealthiness increased the threat of disease. From 1940 to 1960, the infant death rate in the Black Belt was 16% higher than the rest of the city.

Crime in African-American neighborhood

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American ...

s was a low priority to the police. Associated with problems of poverty and southern culture, rates of violence and homicide were high. Some women resorted to prostitution to survive. Both low life and middle-class strivers were concentrated in a small area.

In 1946, the Chicago Housing Authority

The Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) is a municipal corporation that oversees public housing within the city of Chicago. The agency's Board of Commissioners is appointed by the city's mayor, and has a budget independent from that of the city of ...

(CHA) tried to ease the pressure in the overcrowded ghettos and proposed to put public housing sites in less congested areas in the city. The white residents did not take to this very well, so city politicians forced the CHA to keep the status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. ...

and develop high rise projects in the Black Belt and on the West Side. Some of these became notorious failures. As industrial restructuring in the 1950s and later led to massive job losses, residents changed from working-class families to poor families on welfare.

As of May 2016 violence within some Chicago neighborhoods prompted black middle-class people to move to the suburbs.

Culture

Between 1916 and 1920, almost 50,000 Black Southerners moved to Chicago, which profoundly shaped the city's development. Growth increased even more rapidly after 1940. In particular, the new citizens caused the growth of local churches, businesses and community organizations. A new musical culture arose, fed by all the traditions along the Mississippi River. The population continued to increase with new migrants, with the most arriving after 1940. The black arts community in Chicago was especially vibrant. The 1920s were the height of the Jazz Age, but music continued as the heart of the community for decades. Nationally renowned musicians rose within the Chicago world. Along the Stroll, a bright-light district on State Street, jazz greats likeLouis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and Singing, vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and se ...

, Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was bas ...

, Cab Calloway

Cabell Calloway III (December 25, 1907 – November 18, 1994) was an American singer, songwriter, bandleader, conductor and dancer. He was associated with the Cotton Club in Harlem, where he was a regular performer and became a popular vocalis ...

, Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1894 – September 26, 1937) was an American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the " Empress of the Blues", she was the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. Inducted into the Rock an ...

and Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

headlined at nightspots including the Deluxe Cafe.

The literary creation of Black Chicago residents from 1925 to 1950 was also prolific, and the city's Black Renaissance rivaled that of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

. Prominent writers included Richard Wright Richard Wright may refer to:

Arts

* Richard Wright (author) (1908–1960), African-American novelist

* Richard B. Wright (1937–2017), Canadian novelist

* Richard Wright (painter) (1735–1775), marine painter

* Richard Wright (artist) (born 19 ...

, Willard Motley

Willard Francis Motley (July 14, 1909 – March 4, 1965) was an American writer. Motley published a column in the African-American oriented ''Chicago Defender'' newspaper under the pen-name Bud Billiken. He also worked as a freelance writer, and ...

, William Attaway

William Alexander Attaway (November 19, 1911 – June 17, 1986) was an African-American novelist, short story writer, essayist, songwriter, playwright, and screenwriter.

Biography

Early life

Attaway was born on November 19, 1911, in Greenvil ...

, Frank Marshall Davis, St. Clair Drake, Horace R. Cayton, Jr.

Horace Roscoe Cayton Jr. (April 12, 1903 – January 21, 1970) was a prominent American sociologist, newspaper columnist, and writer who specialized in studies of working-class black Americans, particularly in mid-20th-century Chicago. Cayton ...

, and Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. ...

. Chicago was home to writer and poet Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks (June 7, 1917 – December 3, 2000) was an American poet, author, and teacher. Her work often dealt with the personal celebrations and struggles of ordinary people in her community. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poet ...

, known for her portrayals of Black working-class life in crowded tenements of Bronzeville. These writers expressed the changes and conflicts blacks found in urban life and the struggles of creating new worlds. In Chicago, black writers turned away from the folk traditions embraced by Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

writers, instead adopting a grittier style of "literary naturalism" to depict life in the urban ghetto. The classic '' Black Metropolis'', written by St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Jr., exemplified the style of the Chicago writers. Today it remains the most detailed portrayal of Black Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s.

From 2008 to the present, the West Side Historical Society under the guidance of Rickie P. Brown Sr. began to document the rich history of the West Side of Chicago. Their research provided proof of the Austin community having the largest population of Blacks in the city of Chicago. This proved that the largest population of blacks are on its west side, when factoring in the Near West Side, North Lawndale, West Humboldt Park, Garfield Park, and Austin communities as well. Their efforts to build a museum on the west side and continuing to bring awareness to Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Deriving its name from combining "June" and "nineteenth", it is celebrated on the anniversary of General Order No. 3, i ...

as a national holiday was rewarded with a proclamation in 2011 by Governor Pat Quinn.

Business

Chicago's black population developed a class structure, composed of a large number of domestic workers and other manual labourers, along with a small, but growing, contingent of middle-and-upper-class business and professional elites. In 1929, black Chicagoans gained access to city jobs, and expanded their professional class. Fighting job discrimination was a constant battle for African Americans in Chicago, as foremen in various companies restricted the advancement of black workers, which often kept them from earning higher wages. In the mid-20th century, blacks began slowly moving up to better positions in the work force. The migration expanded the market for African-American business. "The most notable breakthrough in black business came in the insurance field." There were four major insurance companies founded in Chicago. Then, in the early 20th century, service establishments took over. The African-American market on State Street during this time consisted of barber shops, restaurants, pool rooms, saloons, and beauty salons. African Americans used these trades to build their own communities. These shops gave the blacks a chance to establish their families, earn money, and become an active part of the community.Politics

With a growing base and strong leadership in machine politics, Blacks began to win elective office in local and state government. The first blacks had been elected to office in Chicago in the late 19th century, decades before the Great Migrations. Chicago elected the first post-Reconstruction African-American member of Congress. He was Republican Oscar Stanton De Priest, in

With a growing base and strong leadership in machine politics, Blacks began to win elective office in local and state government. The first blacks had been elected to office in Chicago in the late 19th century, decades before the Great Migrations. Chicago elected the first post-Reconstruction African-American member of Congress. He was Republican Oscar Stanton De Priest, in Illinois's 1st congressional district

Illinois's first congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Illinois. Based in Cook County, the district includes much of the South Side of Chicago, and continues southwest to Joliet.

From 2003 to early 2013 it ext ...

(1929-1935). The district has continuously elected African-Americans to the office ever since. The Chicago area has elected 18 African Americans to the House of Representatives, more than any state. William L. Dawson represented the Black Belt in Congress from 1943 to his death in office in 1970. He started as a Republican but switched to the Democrats like most of his constituents in the late 1930s. In 1949, he became the first African American to chair a congressional committee.

Chicago is home to three of eight African-American United States senators

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslav ...

who have served since Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, who are all Democrats: Carol Moseley Braun

Carol Elizabeth Moseley Braun, also sometimes Moseley-Braun (born August 16, 1947), is a former U.S. Senator, an American diplomat, politician, and lawyer who represented Illinois in the United States Senate from 1993 to 1999. Prior to her Senate ...

(1993–1999), Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

(2005–2008), and Roland Burris

Roland Wallace Burris (born August 3, 1937) is an American politician and attorney who is a former United States Senator from the state of Illinois and a member of the Democratic Party.

In 1978, Burris was the first African American elected ...

(2009–2010).

Barack Obama moved from the Senate to the White House in 2008.Electing a Black mayor in 1983

In the February 22, 1983, the democrats were split three ways. On the North and Northwest Sides, the incumbent mayorJane Byrne

Jane Margaret Byrne (née Burke; May 24, 1933November 14, 2014) was an American politician who was the first woman to be elected mayor of a major city in the United States. She served as the 50th Mayor of Chicago from April 16, 1979, until April ...

led and future mayor Richard M. Daley

Richard Michael Daley (born April 24, 1942) is an American politician who served as the 54th mayor of Chicago, Illinois, from 1989 to 2011. Daley was elected mayor in 1989 and was reelected five times until declining to run for a seventh term ...

, son of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley, finished a close second. the Black leader Harold Washington

Harold Lee Washington (April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987) was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. Washington became the first African American to be elected as the city's mayor in April 1983. He served as may ...

had massive majorities on the South and West Sides. Southwest Side voters overwhelmingly supported Daley. Washington won with 37% of the vote, versus 33% for Byrne and 30% for Daley. Although winning the Democratic primary was normally considered tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

in heavily Democratic Chicago, after his primary victory Washington found that his Republican opponent, former state legislator Bernard Epton was supported by many high-ranking Democrats and their ward organizations.

Epton's campaign referred to, among other things, Washington's conviction for failure to file income tax returns (he had paid the taxes, but had not filed a return). Washington, on the other hand, stressed reforming the Chicago patronage system and the need for a jobs program in a tight economy. In the April 12, 1983, mayoral general election, Washington defeated Epton by 3.7%, 51.7% to 48.0%, to become mayor of Chicago. Washington was sworn in as mayor on April 29, 1983, and resigned his Congressional seat the following day.

Achievements

In the early 20th century many prominent African Americans were Chicago residents, including Republican and later Democratic congressman William L. Dawson (America's most powerful black politician) and boxing championJoe Louis

Joseph Louis Barrow (May 13, 1914 – April 12, 1981) was an American professional boxer who competed from 1934 to 1951. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential boxers of all time. He re ...

. America's most widely read black newspaper, the ''Chicago Defender

''The Chicago Defender'' is a Chicago-based online African-American newspaper. It was founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott and was once considered the "most important" newspaper of its kind. Abbott's newspaper reported and campaigned against J ...

'', was published there and circulated in the South as well.

After long efforts, in the late 1930s, workers organized across racial lines to form the United Meatpacking Workers of America. By then, the majority of workers in Chicago's plants were black, but they succeeded in creating an interracial organizing committee. It succeeded in organizing unions both in Chicago and Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

, Nebraska, the city with the second largest meatpacking industry. This union belonged to the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

(CIO), which was more progressive than the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

. They succeeded in lifting segregation of job positions. For a time, workers achieved living wages and other benefits, leading to blue collar middle-class life for decades. Some blacks were also able to move up the ranks to supervisory and management positions. The CIO also succeeded in organizing Chicago's steel industry.

Recent decline

A recent report from the Chicago Tribune said thousands of black families have left Chicago in the past decade, lowering the black population by about 10%. Politico reported that Chicago's once wealthy black community has dramatically declined with the shuttering of many black-owned companies. Many blacks leaving Chicago are now recently moving to cities in theU.S. South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, including Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

, Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

, Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 ...

, Little Rock

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

, , Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

.William H. Frey (May 2004).The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-to the present

.

Brookings Institution

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as simply Brookings, is an American research group founded in 1916. Located on Think Tank Row in Washington, D.C., the organization conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in e ...

. brookings.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

Notable people

*

* Bernie Mac

Bernard Jeffrey McCullough (October 5, 1957 – August 9, 2008), better known by his stage name Bernie Mac, was an American comedian and actor. Born and raised on Chicago's South Side, Mac gained popularity as a stand-up comedian. He joined fell ...

* Michelle Obama

Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama (born January 17, 1964) is an American attorney and author who served as first lady of the United States from 2009 to 2017. She was the first African-American woman to serve in this position. She is married t ...

* Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

* Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senato ...

* Dick Gregory

Richard Claxton Gregory (October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017) was an American comedian, civil rights leader, business owner and entrepreneur, and vegetarian activist. His writings were best sellers. Gregory became popular among the Afric ...

* Dwyane Wade

Dwyane Tyrone Wade Jr. (; born January 17, 1982) is an American former professional basketball player. Wade spent the majority of his 16-year career playing for the Miami Heat of the National Basketball Association (NBA) and won three NBA cham ...

* Derrick Rose

Derrick Martell Rose (born October 4, 1988) is an American professional basketball player for the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association (NBA). He played one year of college basketball for the Memphis Tigers before being draft ...

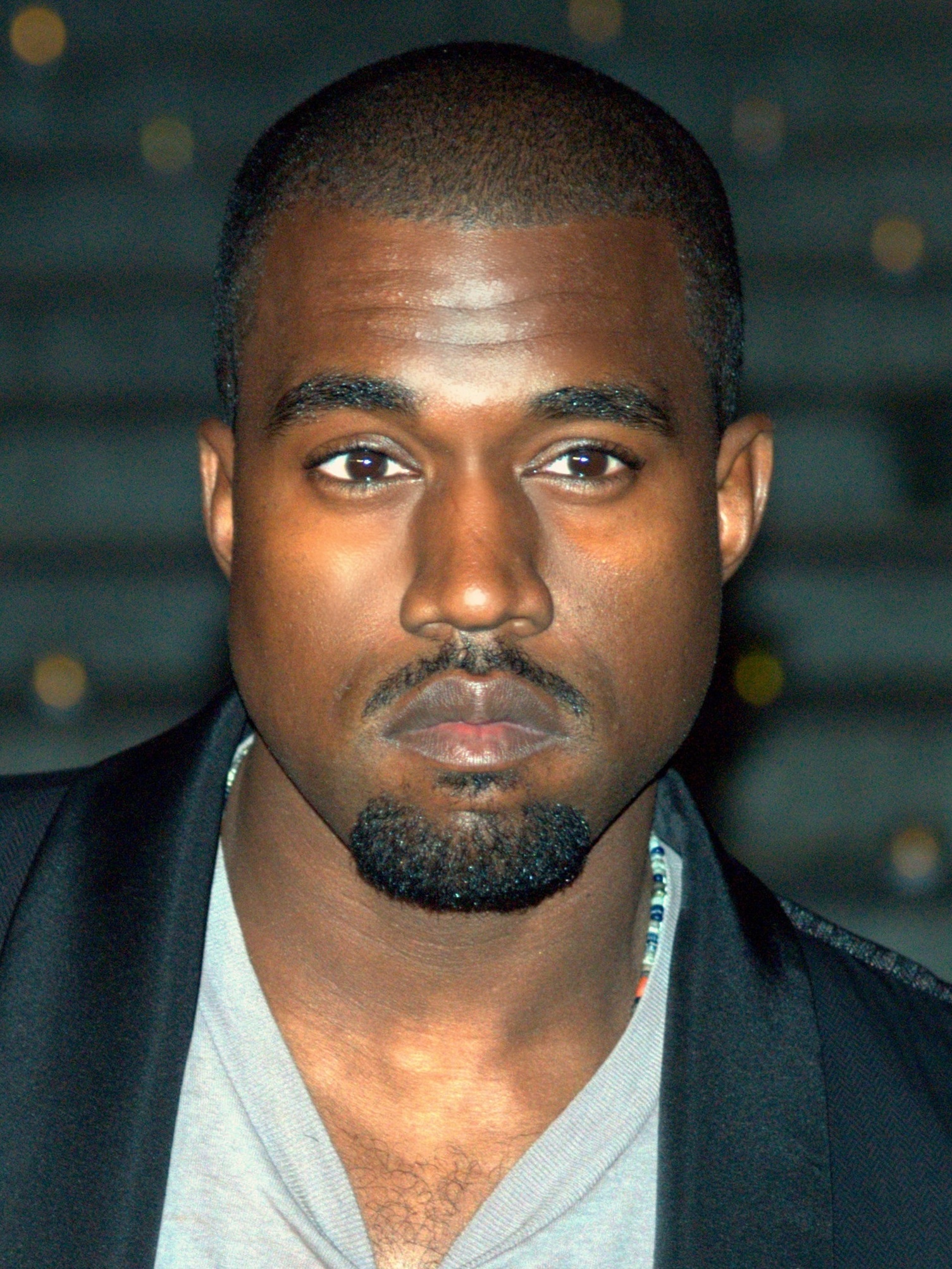

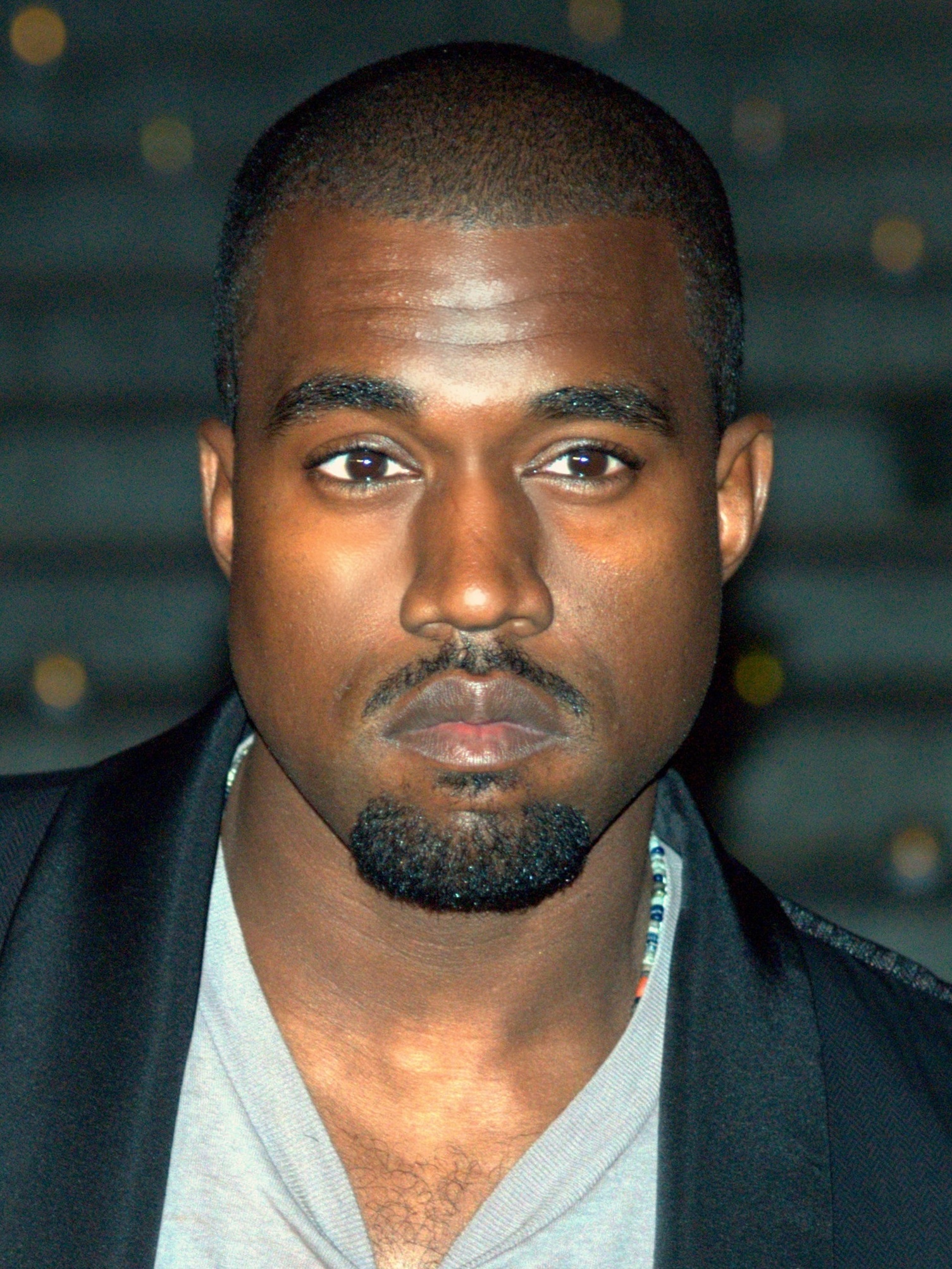

* Kanye West

Ye ( ; born Kanye Omari West ; June 8, 1977) is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, record producer, and fashion designer.

Born in Atlanta and raised in Chicago, West gained recognition as a producer for Roc-A-Fella Records in the ea ...

* Tim Hardaway

Timothy Duane Hardaway Sr. (born September 1, 1966) is an American former professional basketball player. Hardaway played in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the Golden State Warriors, Miami Heat, Dallas Mavericks, Denver Nuggets a ...

* Anthony Davis

Anthony Marshon Davis Jr. (born March 11, 1993) is an American professional basketball player for the Los Angeles Lakers of the National Basketball Association (NBA). He plays the power forward and center positions. Davis is an eight-time ...

* Chance the Rapper

Chancelor Johnathan Bennett (born April 16, 1993), known professionally as Chance the Rapper, is an American rapper, singer-songwriter, and record producer. Born and raised in Chicago, Bennett released his debut mixtape ''10 Day'' in 2012. He ...

* Rhymefest

Che Smith (born July 6, 1977), better known by his stage name Rhymefest, is an American rapper from Chicago whose first official album, '' Blue Collar'', was released in 2006. His prominent songwriting credits include co-writing Kanye West's " ...

* Chief Keef

Keith Farrelle Cozart (born August 15, 1995), better known by his stage name Chief Keef, is an American rapper, singer, songwriter and record producer. His music first became popular during his teen years in the early 2010s among high school s ...

* Redd Foxx

John Elroy Sanford (December 9, 1922 – October 11, 1991), better known by his stage name Redd Foxx, was an American stand-up comedian and actor. Foxx gained success with his raunchy nightclub act before and during the civil rights movement. ...

* Sam Cooke

Samuel Cook (January 22, 1931 – December 11, 1964), known professionally as Sam Cooke, was an American singer and songwriter. Considered to be a pioneer and one of the most influential soul music, soul artists of all time, Cooke is common ...

* Earth, Wind, and Fire

Earth, Wind & Fire (EW&F or EWF) is an American band whose music spans the genres of jazz, R&B, soul, funk, disco, pop, big band, Latin, and Afro pop. They are among the best-selling bands of all time, with sales of over 90 million reco ...

* R. Kelly

* Jennifer Hudson

Jennifer Kate Hudson (born September 12, 1981), also known by her nickname J.Hud, is an American singer, actress, and talk show host. Throughout her career, she has received various accolades for her works in recorded music, film, televisio ...

* Shonda Rhimes

Shonda Lynn Rhimes (born January 13, 1970) is an American television screenwriter, producer, and author. She is best known as the showrunner—creator, head writer, and executive producer—of the television medical drama '' Grey's Anatomy'', ...

* Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

* Curtis Mayfield

Curtis Lee Mayfield (June 3, 1942 – December 26, 1999) was an American singer-songwriter, guitarist, and record producer, and one of the most influential musicians behind soul and politically conscious African-American music.

* Minnie Riperton

Minnie Julia Riperton Rudolph (November 8, 1947 – July 12, 1979)

was an American singer-songwriter best known for her 1975 single " Lovin' You" and her four octave D3 to F7 coloratura soprano range. She is also widely known for her use ...

* Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and Singing, vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and se ...

* Muddy Waters

McKinley Morganfield (April 4, 1913 April 30, 1983), known professionally as Muddy Waters, was an American blues singer and musician who was an important figure in the post- war blues scene, and is often cited as the "father of modern Chicag ...

* Ida B Wells

Ida B. Wells (full name: Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the Civil rights movement (1896–1954), civil rights movement. She was one of the foun ...

* Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African Americans, African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and Lynching in the United States, lynched in Mississippi in 1955, after being accused of offending a whi ...

* Lil Durk

Durk Derrick Banks (born October 19, 1992), known professionally as Lil Durk, is an American rapper and singer. He is the lead member and founder of the collective and record label Only the Family (OTF). Durk garnered a cult following with the ...

* King Von

Dayvon Daquan Bennett (August 9, 1994 – November 6, 2020), known professionally as King Von, was an American rapper from Chicago, Illinois. He was signed to Lil Durk's record label Only the Family and Empire Distribution.

Early life

Benne ...

* G Herbo

Herbert Randall Wright III (born October 8, 1995), better known by his stage name G Herbo (formerly Lil Herb), is an American rapper from Chicago.

G Herbo is signed to Machine Entertainment Group. He has released the mixtapes '' Welcome to Fa ...

* Lil Bibby

Brandon George Dickinson (born July 18, 1994), better known by his stage name Lil Bibby, is an American rapper and record executive. Beginning his career in 2011, Bibby released his debut mixtape in 2013, titled '' Free Crack''. After signing wi ...

* Juice WRLD

Jarad Anthony Higgins (December 2, 1998 – December 8, 2019), known professionally as Juice Wrld (pronounced "juice world"; stylized as Juice WRLD), was an American rapper, singer, and songwriter. He was a leading figure in the emo rap and ...

* Polo G

Taurus Tremani Bartlett (born January 6, 1999), known professionally as Polo G, is an American rapper. He rose to prominence with his singles " Finer Things" and "Pop Out" (featuring Lil Tjay). His debut album '' Die a Legend'' (2019) peaked at ...

* Dreezy

Seandrea Sledge (born March 28, 1994), better known by her stage name Dreezy, is an American rapper and singer. She signed with Interscope Records in 2014 where she released the studio albums '' No Hard Feelings'' (2016) and '' Big Dreez'' (201 ...

* Cupcakke

Elizabeth Eden Harris (born May 31, 1997), known professionally as Cupcakke (often stylized as CupcakKe; pronounced ), is an American rapper from Chicago, Illinois. She is known for her hypersexualised, brazen, and often comical persona and mus ...

* Buddy Guy

George "Buddy" Guy (born July 30, 1936) is an American blues guitarist and singer. He is an exponent of Chicago blues who has influenced generations of guitarists including Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Stevie Ray Vaugh ...

* Nat King Cole

Nathaniel Adams Coles (March 17, 1919 – February 15, 1965), known professionally as Nat King Cole, was an American singer, jazz pianist, and actor. Cole's music career began after he dropped out of school at the age of 15, and continued f ...

* Harold Washington

Harold Lee Washington (April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987) was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. Washington became the first African American to be elected as the city's mayor in April 1983. He served as may ...

* Lupe Fiasco

Wasalu Muhammad Jaco (born February 16, 1982), better known by his stage name Lupe Fiasco ( ), is an American rapper, singer, record producer, and entrepreneur. He rose to fame in 2006 following the success of his debut album, '' Lupe Fiasco's ...

* Twista

Carl Terrell Mitchell (born November 27, 1973), better known by his stage name Twista (formerly Tung Twista), is an American rapper and record producer. He is best known for his chopper style of rapping and for once holding the title of fastes ...

* Common

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally ...

* Chaka Khan

Yvette Marie Stevens (born March 23, 1953), better known by her stage name Chaka Khan (), is an American singer. Her career has spanned more than five decades, beginning in the 1970s as the lead vocalist of the funk band Rufus. Known as the " Q ...

* Keke Palmer

Lauren Keyana "Keke" Palmer (born August 26, 1993) ( ) is an American actress, singer and television personality. Known for playing leading and character roles in comedy and drama productions, she has received a Primetime Emmy Award, five NAACP I ...

* Noname

* Dantrell Davis

Dantrell Davis (July 31, 1985 – October 13, 1992) was a 7-year-old boy from Chicago, Illinois, who was murdered in October 1992. Davis was walking to school with his mother in the Cabrini-Green housing projects when he was accidentally shot b ...

See also

*African Americans in New York City

African Americans constitute one of the longer-running ethnic presences in New York City, home to the largest urban African American population, and the world's largest Black population of any city outside Africa, by a significant margin.

Pop ...

*History of African Americans in Philadelphia

This article documents the history of African-Americans or Black Philadelphians in Philadelphia.

Recent 2010 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau put the total number of people living in Philadelphia who identify as Black or African-American a ...

*History of African Americans in Detroit

Black Detroiters are black or African American residents of Detroit. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Black or African Americans living in Detroit accounted for 79.1% of the total population, or approximately 532,425 people as of 2017 estim ...

*History of African Americans in Boston

Until 1950, African Americans were a small but historically important minority in Boston, where the population was majority white. Since then, Boston's demographics have changed due to factors such as immigration, white flight, and gentrificat ...

* African Americans in Baltimore

*Chicago Black Renaissance

The Chicago Black Renaissance (also known as the Black Chicago Renaissance) was a creative movement that blossomed out of the Chicago Black Belt on the city's South Side and spanned the 1930s and 1940s before a transformation in art and cultur ...

*Chicago State University

Chicago State University (CSU) is a predominantly black public university in Chicago, Illinois. Founded in 1867 as the Cook County Normal School, it was an innovative teachers college. Eventually the Chicago Public Schools assumed control of t ...

*Chicago Race Riot of 1919

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a violent racial conflict between white Americans and black Americans that began on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. During the riot, 38 people died (23 black a ...

*Great Migration (African American)

The Great Migration, sometimes known as the Great Northward Migration or the Black Migration, was the movement of six million African Americans out of the rural Southern United States to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West between 1910 and ...

*Second Great Migration (African American)

In the context of the 20th-century history of the United States, the Second Great Migration was the migration of more than 5 million African Americans from the South to the Northeast, Midwest and West. It began in 1940, through World War II ...

*History of Chicago

Chicago has played a central role in American economic, cultural and political history. Since the 1850s Chicago has been one of the dominant metropolises in the Midwestern United States, and has been the largest city in the Midwest since the 1 ...

* Political history of Chicago

* Demographics of Chicago

* Ethnic groups in Chicago

*George Floyd protests in Chicago

The George Floyd protests in Chicago were a series of civil disturbances in 2020 in the city of Chicago, Illinois. Unrest in the city began as a response to the murder of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. The demon ...

*Puerto Ricans in Chicago

Puerto Ricans in Chicago are people living in Chicago who have ancestral connections to the island of Puerto Rico. They have contributed to the economic, social and cultural well-being of Chicago for more than seventy years.

History

The Pu ...

*Mexicans in Chicago

There is a very large Mexican American community in the Chicago metropolitan area. Illinois, and Chicago's Mexican American community is the largest outside of the Western United States.

History

The first Mexicans who came to Chicago, mostly e ...

*Italians in Chicago

Chicago and its suburbs have a historical population of Italian Americans. As of 2000, about 500,000 in the Chicago area identified themselves as being Italian descent.Vecoli, Rudolph J.ItaliansArchive). ''Encyclopedia of Chicago''. Retrieved on ...

* Koreans in Chicago

* Germans in Chicago

* Czechs in Chicago

*Bosnians in Chicago

The city of Chicago, Illinois, is tied with St. Louis for largest Bosnian-American population and the largest number of Bosnians outside of Europe, The largest concentration of Bosnians in Chicago live on the North Side.

History

The first Bos ...

* Swedes in Chicago

*Japanese in Chicago

Among the Japanese in the Chicago metropolitan area, there are Japanese-American and Japanese expatriate populations. Early Japanese began arriving around the time of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. During World War II, Japanese-Amer ...

*Indians in Chicago

The Chicago metropolitan area has a large Indian Americans, Indian American population. As of 2010, there are 171,901 Indian Americans living in the Chicago area, making it the most populous Asian subgroup in the metropolitan area and the second- ...

References

Further reading

* Anderson, Alan B., and George W. Pickering. ''Confronting the Color Line: The Broken Promise of Civil Rights Movements in Chicago'' (University of Georgia Press, 1986). * Best, Wallace"Black Belt,"

in ''

Encyclopedia of Chicago

''The Encyclopedia of Chicago'' is a historical reference work covering Chicago and the entire Chicago metropolitan area published by the University of Chicago Press. Released in October 2004, the work is the result of a ten-year collaboration ...

'', 2007; p. 140.

* Best, Wallace D. Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952

'. (Princeton University Press, 2007: , 2013) * Bowly, Devereaux, Jr. ''The Poorhouse: Subsidized Housing in Chicago, 1895–1976'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 1978). * Branch, Taylor. ''Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1964–1965'' (1998). * Cohen, Adam, and Elizabeth Taylor. ''American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley-his battle for Chicago and the nation'' (2001, ) * Coit, Jonathan S., "'Our Changed Attitude': Armed Defense and the New Negro in the 1919 Chicago Race Riot", ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 11 (April 2012), 225–56. * * Dolinar, Brian (ed.)

''The Negro in Illinois. The WPA Papers''

University of Chicago Press, cloth: 2013, ; paper, : 2015. Produced by a special division of the Illinois Writers' Project, part of the

Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers during the Great Depression. It was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program. It wa ...

, one of President Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

programs of the 1930s, with black writers living in Chicago during the 1930s, including Richard Wright Richard Wright may refer to:

Arts

* Richard Wright (author) (1908–1960), African-American novelist

* Richard B. Wright (1937–2017), Canadian novelist

* Richard Wright (painter) (1735–1775), marine painter

* Richard Wright (artist) (born 19 ...

, Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. ...

, Katherine Dunham

Katherine Mary Dunham (June 22, 1909 – May 21, 2006) was an American dancer, choreographer, anthropologist, and social activist. Dunham had one of the most successful dance careers of the 20th century, and directed her own dance company for m ...

, Fenton Johnson

John Fenton Johnson is an American writer and professor of English and LGBT Studies at the University of Arizona.

Life

He was born ninth of nine children into a Kentucky whiskey-making family with a strong storytelling tradition.

In February ...

, Frank Yerby

Frank Garvin Yerby ( – ) was an American writer, best known for his 1946 historical novel ''The Foxes of Harrow''.

Early life

Yerby was born in Augusta, Georgia, on September 5, 1916, the second of four children of Rufus Garvin Yerby (1886– ...

, and Richard Durham

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

.

* Drake, St. Clair, and Horace Cayton. ''Black Metropolis: A Study in Negro Life in a Northern City'' (1945) a famous scholarly studyonline

* Frady, Marshall. ''Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson'' (1996) * Fremon, David. ''Chicago Politics Ward by Ward'' (Indiana University Press, 1988). * Garrow, David J. ed. ''Chicago 1966: Open Housing Marches, Summit Negotiations, and Operation Breadbasket'' (1989). * Garb, Margaret

(University of Chicago Press, 2014, ) * Gordon, Rita Werner. "The change in the political alignment of Chicago's Negroes during the New Deal." ''Journal of American History'' 56.3 (1969): 584-603. * Gosnell, Harold F. "The Chicago 'Black belt' as a political battleground." ''American Journal of Sociology'' 39.3 (1933): 329-341. * Gosnell, Harold F. ''Negro Politicians; The Rise of Negro Politics in Chicago'' (University of Chicago Press. 1935)

online

also see

online review

* Green, Adam

(University of Chicago Press, 2009, ) * Grimshaw, William J. ''Bitter Fruit: Black Politics and the Chicago Machine, 1931–1991'' (University of Chicago Press, 1992). * Grossman, James R. ''Land of hope: Chicago, black southerners, and the great migration'' (University of Chicago Press, 1991) * Halpern, Rick. ''Down on the Killing Floor: Black and White Workers in Chicago's Packinghouses, 1904-54'' (University of Illinois Press, 1997). * Helgeson, Jeffrey

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, . * Hirsch, Arnold Richard.

'. (University of Chicago Press, 1998, ) * Kenney, William Howland

''Chicago jazz: A cultural history, 1904-1930''

(Oxford University Press, 1993) * Kimble Jr., Lionel. ''A New Deal for Bronzeville: Housing, Employment, and Civil Rights in Black Chicago, 1935–1955'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, ). xiv, 200 pp. * Kleppner, Paul. ''Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor'' (Northern Illinois University Press, 1985); 1983 election of

Harold Washington

Harold Lee Washington (April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987) was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. Washington became the first African American to be elected as the city's mayor in April 1983. He served as may ...

* Knupfer, Anne Meis. "'Toward a Tenderer Humanity and a Nobler Womanhood': African-American Women's Clubs in Chicago, 1890 to 1920." ''Journal of Women's History

The ''Journal of Women's History'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal established in 1989 covering women's history. It explores multiple perspectives of feminism rather than promoting a single unifying form. Articles published in this ...

'' 7#3 (1995): 58–76.

* Lemann, Nicholas. ''The Promised Land: The Great Migration and How It Changed America'' (1991).

* McClelland, Ted. ''Young Mr. Obama: Chicago and the making of a Black president'' (2010online

* McGreevy, John T. ''Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the TwentiethCentury Urban North'' (University of Chicago Press, 1996)

excerpt

* Manning, Christopher

in ''Encyclopedia of Chicago.'' (2007); p. 27. * Philpott, Thomas Lee. ''The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterioration and Middle Class Reform, Chicago, 1880–1930'' (Oxford University Press, 1978). * Pickering, George W. ''Confronting the Color Line: The Broken Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in Chicago'' (University of Georgia Press, 1986). * Pinderhughes, Dianne Marie.

Race and ethnicity in Chicago politics: A reexamination of pluralist theory

' (University of Illinois Press, 1987) * Reed, Christopher. ''The Chicago NAACP and the Rise of the Black Professional Leadership, 1910–1966'' (Indiana University Press, 1997). * Rivlin, Gary. ''Fire on the prairie: Chicago's Harold Washington and the politics of race'' (Holt, 1992, ) * Rocksborough-Smith, Ian. ''Margaret T.G. Burroughs and Black Public History in Cold War Chicago''.

The Black Scholar

''The Black Scholar'' (''TBS''), the third-oldest journal of Black culture and political thought in the United States, was founded in 1969 near San Francisco, California, by Robert Chrisman, Nathan Hare, and Allan Ross. It is arguably the most i ...

'', (2011), Vol. 41(3), pp. 26–42.

* Smith, Preston H. ''Racial democracy and the Black metropolis: Housing policy in postwar Chicago'' ( U of Minnesota Press, 2012).

* Spaulding, Norman W''History of Black oriented radio in Chicago, 1929-1963''

(PhD disst. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1981. * Spear, Allan H

(University of Chicago Press, 1967, ) * Street, Paul. "The 'Best Union Members': Class, Race, Culture, and Black Worker Militancy in Chicago's Stockyards during the 1930s." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' (2000): 18-49

online