Bill O'Reilly (cricketer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Joseph O'Reilly OBE (20 December 19056 October 1992) was an Australian

O'Reilly became a regular member of the Australian Test side in the 1932–33 season and he played in all five Tests against

O'Reilly became a regular member of the Australian Test side in the 1932–33 season and he played in all five Tests against

With Bradman's appointment as captain of the Australian team after the South African tour,

With Bradman's appointment as captain of the Australian team after the South African tour,  In the 1937–38 season, O'Reilly returned to more regular state cricket, and New South Wales duly won the Sheffield Shield for the first time in five seasons. He took 33 wickets at an average of just over 14 runs each, and against

In the 1937–38 season, O'Reilly returned to more regular state cricket, and New South Wales duly won the Sheffield Shield for the first time in five seasons. He took 33 wickets at an average of just over 14 runs each, and against

' s 1939 edition noted that "it was nothing short of remarkable that despite the moderate support accorded to him he bowled so consistently well and so effectively." Again, O'Reilly was often used defensively where there was no help from the wicket, but, ''Wisden'' added, "when... the wicket gave him the least encouragement he robbed the greatest batsmen of initiative, and was most destructive".

O'Reilly took 3/164 on a batting paradise in the First Test at

cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

er, rated as one of the greatest bowlers in the history of the game. Following his retirement from playing, he became a well-respected cricket writer and broadcaster.

O'Reilly was one of the best spin bowlers ever to play cricket. He delivered the ball

A ball is a round object (usually spherical, but can sometimes be ovoid) with several uses. It is used in ball games, where the play of the game follows the state of the ball as it is hit, kicked or thrown by players. Balls can also be used f ...

from a two-fingered grip at close to medium pace

Fast bowling (also referred to as pace bowling) is one of two main approaches to bowling in the sport of cricket, the other being spin bowling. Practitioners of pace bowling are usually known as ''fast'' bowlers, ''quicks'', or ''pacemen''. T ...

with great accuracy, and could produce leg break

Leg spin is a type of spin bowling in cricket. A leg spinner bowls right-arm with a wrist spin action. The leg spinner's normal delivery causes the ball to spin from right to left (from the bowler's perspective) when the ball bounces on the ...

s, googlies, and top spinners, with no discernible change in his action.Wisden (1935), pp.

284–286. A tall man for a spinner (around 188 cm, 6 ft 2 in), he whirled his arms to an unusual extent and had a low point of delivery that meant it was very difficult for the batsman to read the flight of the ball out of his hand. When O'Reilly died, Sir Donald Bradman

Sir Donald George Bradman, (27 August 1908 – 25 February 2001), nicknamed "The Don", was an Australian international cricketer, widely acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time. Bradman's career Test batting average of 99.94 has bee ...

said that he was the greatest bowler he had ever faced or watched. In 1935, ''Wisden

''Wisden Cricketers' Almanack'', or simply ''Wisden'', colloquially the Bible of Cricket, is a cricket reference book published annually in the United Kingdom. The description "bible of cricket" was first used in the 1930s by Alec Waugh in a ...

'' wrote of him: "O'Reilly was one of the best examples in modern cricket of what could be described as a 'hostile' bowler." In 1939, ''Wisden'' reflected on Bill O'Reilly's successful 1938

Events

January

* January 1

** The new constitution of Estonia enters into force, which many consider to be the ending of the Era of Silence and the authoritarian regime.

** State-owned railway networks are created by merger, in France ...

Ashes

Ashes may refer to:

* Ash, the solid remnants of fires.

Media and entertainment Art

* ''Ashes'' (Munch), an 1894 painting by Edvard Munch

Film

* ''The Ashes'' (film), a 1965 Polish film by director Andrzej Wajda

* ''Ashes'' (1922 film), ...

tour of England: "He is emphatically one of the greatest bowlers of all time."Wisden, p. 197.

As a batsman

In cricket, batting is the act or skill of hitting the cricket ball, ball with a cricket bat, bat to score runs (cricket), runs and prevent the dismissal (cricket), loss of one's wicket. Any player who is currently batting is, since Septembe ...

, O'Reilly was a competent right-hander, usually batting well down the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

. O'Reilly's citation as a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1935 said: "He had no pretensions to grace of style or any particular merit, but he could hit tremendously hard and was always a menace to tired bowlers."

As well as his skill, O'Reilly was also known for his competitiveness, and he bowled with the aggression of a paceman. In a short biographical essay on O'Reilly for the ''Barclays World of Cricket'' book, contemporary England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

cricketer Ian Peebles

Ian or Iain is a name of Scottish Gaelic origin, derived from the Hebrew given name (Yohanan, ') and corresponding to the English name John. The spelling Ian is an Anglicization of the Scottish Gaelic forename ''Iain''. It is a popular name in Sc ...

wrote that "any scoring-stroke was greeted by a testy demand for the immediate return of the ball rather than a congratulatory word. Full well did he deserve his sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ), or soubriquet, is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another, that is descriptive. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym, as it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name, without the need of expla ...

of 'Tiger'."

Youth and early career

OfIrish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

descent, O'Reilly's paternal grandfather Peter emigrated from County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; gle, Contae an Chabháin) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Ulster and is part of the Border Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is based on the historic Gaelic territory of East Breffny (''Bréifn ...

, Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

in 1865. Arriving in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, he had been a policeman for four years in Ireland and continued in this line of work in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. He was sent to Deniliquin

Deniliquin () is a town in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia, close to the border with Victoria. It is the largest town in the Edward River Council local government area.

Deniliquin is located at the intersection of the Riverina ...

in the Riverina

The Riverina

is an agricultural region of south-western New South Wales, Australia. The Riverina is distinguished from other Australian regions by the combination of flat plains, warm to hot climate and an ample supply of water for irrigation ...

, where he settled and married another Irish immigrant Bridget O'Donoghue from Ballinasloe

Ballinasloe ( ; ) is a town in the easternmost part of County Galway in Connacht. Located at an ancient crossing point on the River Suck, evidence of ancient settlement in the area includes a number of Bronze Age sites. Built around a 12th-ce ...

, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

. O'Reilly's father, Ernest, was a school teacher and moved around the areas surrounding the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest ...

to study and teach. O'Reilly's mother Mina (née Welsh) was of mixed Irish and English descent, of a third generation family from Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. O'Reilly was born in the opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Due to its amorphous property, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline form ...

mining town of White Cliffs, New South Wales

White Cliffs is a small town in outback New South Wales in Australia, in Central Darling Shire. White Cliffs is around 255 km northeast of Broken Hill, 93 km north of Wilcannia. At the , White Cliffs had a population of 156.

The prim ...

. Ernest had been appointed to open the first school in the town,Whitington, p. 113.Engel, p. 44. and had helped to build the school and its furniture himself.McHarg, p. 27. Bill was the fourth child in the family, with two elder brothers and a sister.Whitington, p. 114.

O'Reilly's cricket skills were largely self-taught; his family moved from town to town whenever his father was posted to a different school, he had little opportunity to attend coaching. He learned to play with his brothers, playing with a " gum-wood bat and a piece of banksia

''Banksia'' is a genus of around 170 species in the plant family Proteaceae. These Australian wildflowers and popular garden plants are easily recognised by their characteristic flower spikes, and fruiting "cones" and heads. ''Banksias'' range ...

root chiselled down to make a ball." He learned to bowl because his older brothers dominated the batting rights. His bowling action was far from the classic leg spin

Leg spin is a type of spin bowling in cricket. A leg spinner bowls right-arm with a wrist spin action. The leg spinner's normal delivery causes the ball to spin from right to left (from the bowler's perspective) when the ball bounces on the ...

bowler's run-up and delivery, indeed, according to ''Wisden'', "he was asked to make up the numbers in a Sydney junior match and, with a method that at first made everyone giggle, whipped out the opposition". From a young age, O'Reilly was a tall and gangly player.

In January 1908, shortly after Bill had turned two, the family moved to Murringo

Murringo is a small village in the southwestern slopes of New South Wales, Australia in Hilltops Council. It was once better known as Marengo.

History

The area now known as Murringo lies on the traditional lands of the Wiradjuri people, clos ...

, after Ernest was appointed the headmaster.Whitington, p. 117. O'Reilly said in his autobiography ''Tiger'' that the move played no vital part in his cricket education. The area had much more vegetation than the desolate White Cliffs, and an Irish Australian majority. O'Reilly later described the period as the happiest of his life.McHarg, p. 29. There the children played tennis on a court on their property and took up cricket. During this time, O'Reilly's mother gave birth to another son and two more daughters.Whitington, p. 118. In 1917, at the age of 12, the family moved to the town of Wingello

Wingello () is a village in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia. It has a station on NSW TrainLink's Southern Highlands Line. The surrounding area is part of the lands administrative unit of the Wingello Parish, a subdivisi ...

. Ernest made the decision because there were no high schools near Murringo and his older children were about to finish primary school. Nevertheless, there was no high school in Wingello where Ernest had been appointed headmaster, so O'Reilly had to catch a train to Goulburn

Goulburn ( ) is a regional city in the Southern Tablelands of the Australian state of New South Wales, approximately south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Canberra. It was proclaimed as Australia's first inland city through letters pate ...

—50 km away—to study at the local public secondary school, where his elder brother Tom had been awarded a scholarship.McHarg, p. 31. Wingello was a cricket town and "everyone was a cricket crank" according to O'Reilly. It was here that he developed a passion for the game. O'Reilly played in the town's team and also won the regional tennis championships. O'Reilly bowled with an action reminiscent of the windmill that his family erected in the town.Whitington, p. 124. However, school life was difficult, especially in the winter, as the Southern Tablelands were harsh and cold. The O'Reilly children had to leave Wingello at 7.45 am by rail and caught a slow goods train that delivered them home at 7 pm; these vehicles did not provide protection against the weather, and the boys did not participate in any school sport as the only train home left after the end of classes.McHarg, p. 32.

In the early 1920s, O'Reilly's eldest brother Jack moved to Sydney. One afternoon, Jack watched spin bowler Arthur Mailey

Alfred Arthur Mailey (3 January 188631 December 1967) was an Australian cricketer who played in 21 Test matches between 1920 and 1926.

Mailey used leg-breaks and googly bowling, taking 99 Test wickets, including 36 in the 1920–21 Ashes ser ...

in the North Sydney practice nets and managed to describe the famous bowler's ' Bosie' action in a letter to Bill.Whitington, p. 128. O'Reilly claims to have perfected the action of changing the spin from anticlockwise to clockwise without any discernible hand movement within a couple of days. O'Reilly said that "The bosie became my most prized possession. I practised day in, day out".

Ernest decided that the train journeys and frozen limbs were too much for his son, so he sent Bill to St Patrick's College, Goulburn

(If you do something, do it well)

, status = Closed

, established =

, closed = 2000 (merged into Trinity Catholic College, Goulburn)

, city = Goulburn

, state = New South Wales

, country = Australia

, campus =

, coo ...

as a boarder in 1921, where he quickly showed his athletic flair by becoming a member of the school's rugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as just rugby league and sometimes football, footy, rugby or league, is a full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular field measuring 68 metres (75 yards) wide and 112 ...

, tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball cov ...

, athletics

Athletics may refer to:

Sports

* Sport of athletics, a collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking

** Track and field, a sub-category of the above sport

* Athletics (physical culture), competi ...

and cricket teams. He held a state record for the triple jump

The triple jump, sometimes referred to as the hop, step and jump or the hop, skip and jump, is a track and field event, similar to the long jump. As a group, the two events are referred to as the "horizontal jumps". The competitor runs down th ...

. At the same time, he also represented the town team. During his time at St Patrick's, O'Reilly developed his ruthless and parsimonious attitude towards bowling.McHarg, p. 33. After three years at the Irish Catholic school, funded by a scholarship, O'Reilly completed his Leaving Certificate.McHarg, p. 32.

Sydney Teachers College

O'Reilly won a scholarship to the Sydney Teachers College atSydney University

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's six ...

, to train as a schoolmaster. However, the financial assistance was only for two years and merely sufficient for O'Reilly's rent at Glebe Point

Glebe Point is a point on Sydney Harbour in the suburb of Glebe, in the Inner West of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia.

External links

GlebeNet: Information for Residents and Visitors to Glebe, Sydney

File:Glebe_Point.JPG, Gl ...

. When he was in Sydney, O'Reilly received an invitation to join an athletics club based on his performances in Goulburn, but was only able to join after the secretary Dick Corish waived his membership fee.McHarg, p. 34. Jumping 47 feet, he came second in a triple jump

The triple jump, sometimes referred to as the hop, step and jump or the hop, skip and jump, is a track and field event, similar to the long jump. As a group, the two events are referred to as the "horizontal jumps". The competitor runs down th ...

competition behind Nick Winter

Anthony William "Nick" Winter (25 August 1894 – 6 May 1955) was an Australian sportsman. He won the gold medal in the triple jump at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, in the process setting a new world record. His medal-winning jump r ...

, who went on to win gold in the event at the 1924 Summer Olympics

The 1924 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1924), officially the Games of the VIII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIIe olympiade) and also known as Paris 1924, were an international multi-sport event held in Paris, France. The o ...

with a world record of 50 ft. O'Reilly also placed second in a high jumping competition, clearing six feet.Whitington, p. 126. Corish was also a cricket administrator and invited O'Reilly to play in a David Jones Second XI. Not knowing anything of his new recruit's abilities, Corish did not allow O'Reilly to bowl until he explicitly complained of only being allowed to field. O'Reilly promptly finished off the opposition's innings by removing the middle and lower order. After an encounter with journalist Johnny Moyes

Alban George "Johnny" Moyes (2 January 1893 – 18 January 1963) was a cricketer who played for South Australia and Victoria. Following his brief playing career, Moyes, a professional journalist, later gained greater fame as a writer and comme ...

, who wrote glowingly about O'Reilly's skills.

While training as a teacher, O'Reilly joined the Sydney University Regiment

Sydney University Regiment (SUR) is an officer-training regiment of the Australian Army Reserve. Its predecessor, the University Volunteer Rifle Corps, was raised in 1900 as a unit of the colonial New South Wales Defence Force. During the 20th ...

, a unit of the Militia Forces (Army Reserve). He did not enjoy his time in the military, and along with most of his peers, regarded the commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

as inept. O'Reilly was a non-conformist who did not enjoy taking orders, and was unimpressed with the firearm drills, because the recruits were armed only with wooden sticks. However, he signed up for a second year to raise money for his education. Fed up with military routines he considered to be pointless, O'Reilly volunteered to be a kitchen hand.

During a vacation, O'Reilly caught the train from Sydney back to Wingello, which stopped at Bowral

Bowral () is the largest town in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, about ninety minutes southwest of Sydney. It is the main business and entertainment precinct of the Wingecarribee Shire and Highlands.

Bowral once served ...

mid-journey. There, Wingello were playing the host town in a cricket match, and O'Reilly was persuaded to interrupt his journey to help his teammates. This match marked his first meeting with Bowral's 17-year-old Don Bradman, later to become his Test captain. O'Reilly himself later described thus:

The wicket ended a period of suffering for O'Reilly at the hands of Bradman, who had hit many fours and sixes

Sixes, home to approximately 14,540, is an unincorporated community in western Cherokee County, Georgia, United States, located about three miles west of Holly Springs and near the eastern shore of current-day Lake Allatoona. The community i ...

from him. Bradman's counter-attack came after he had been dropped twice from O'Reilly's bowling before reaching 30 by Wingello's captain Selby Jeffery. On the first occasion, the ball hit Jeffery in the chest while he was lighting his pipe; soon after the skipper failed to see the ball "in a dense cloud of bluish smoke" as he puffed on his tobacco.McHarg, p. 39. The match was the start of a long on-field relationship between the pair, who were to regard one another as the best in the world in their fields. O'Reilly recalled that Bradman "knew what the game was all about".McHarg, p. 38.

O'Reilly did not enjoy his time at the overcrowded Sydney Teachers College (STC), decrying the lack of practical training and the predominance of pedagogical theory. Regarding it as a waste of time, he happily accepted an offer of work experience from Major Cook-Russell, the head of physical education at STC, to help at Naremburn College instead of attending lectures. This angered Professor Alexander Mackie, the head of STC, whom both Cook-Russell and O'Reilly regarded as incompetent.McHarg, p. 36.

O'Reilly's initial posting after abandoning his training was to a government school in Erskineville, an inner-city suburb in Sydney. At the time, the suburb was slum-like and impoverished, with many unruly students. Many of the pupils were barely clothed and tested O'Reilly's ability to discipline. He said that he learned more in three months there under Principal Jeremiah Walsh than he would have in ten years at STC.McHarg, p. 37. Major Cook-Russell then started a military cadet program in New South Wales schools; O'Reilly started such a program at Erskineville and his students won the statewide competition "in a canter".McHarg, p. 38. O'Reilly's time at Erskineville also marked the start of work-sport conflicts that hampered his cricket career. He joined North Sydney Cricket Club

UTS North Sydney Cricket Club, formerly known as North Sydney District Cricket Club, is a cricket club based in North Sydney, Australia. The Bears, as they are known, were founded in 1858 playing against Callen Park and other cricket clubs arou ...

in 1926–27 and was selected at short notice to play in an invitational match under retired Australian captain Monty Noble

Montague Alfred Noble (28 January 1873 – 22 June 1940) was an Australian cricketer who played for New South Wales and Australia. A right-hand batsman, right-handed bowler who could deliver both medium pace and off-break bowling, capable field ...

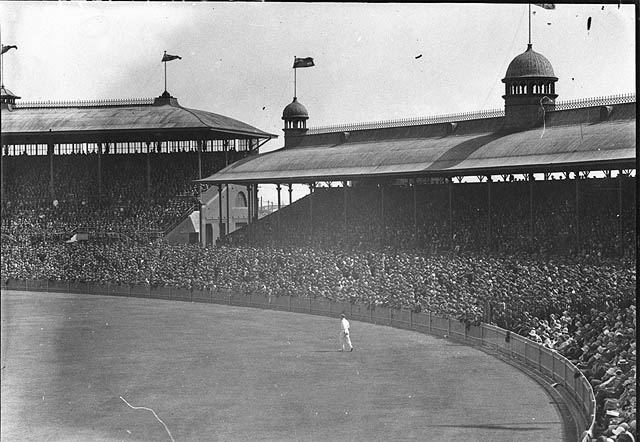

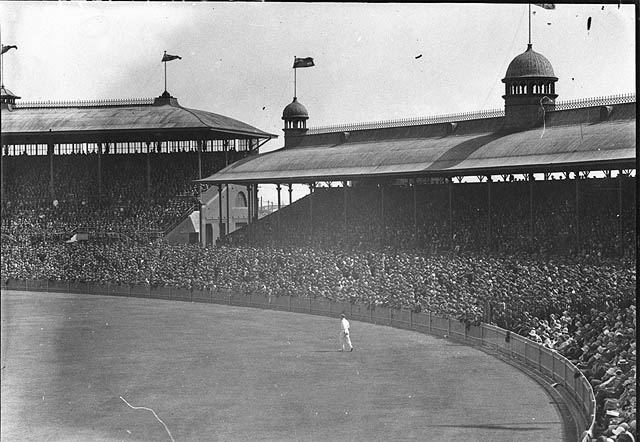

at the Sydney Cricket Ground

The Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) is a sports stadium in Sydney, Australia. It is used for Test, One Day International and Twenty20 cricket, as well as, Australian rules football and occasionally for rugby league, rugby union and association f ...

. As the education department required a week's notice for leave requests, O'Reilly declined, but was then ordered by the Chief Inspector of Schools to play after turning up at school on the morning of the match. Having taken six wickets, the match was then washed out, and O'Reilly then had his pay deducted, much to his chagrin.McHarg, p. 39.

First-class career

Debut

O'Reilly was selected for theNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

practice squad based on his performance in a single match for North Sydney against Gordon in 1927–28. In this game, he bowled Moyes—a state selector—with a medium paced leg break

Leg spin is a type of spin bowling in cricket. A leg spinner bowls right-arm with a wrist spin action. The leg spinner's normal delivery causes the ball to spin from right to left (from the bowler's perspective) when the ball bounces on the ...

. At state training, O'Reilly's new teammate and Test leg spinner Arthur Mailey

Alfred Arthur Mailey (3 January 188631 December 1967) was an Australian cricketer who played in 21 Test matches between 1920 and 1926.

Mailey used leg-breaks and googly bowling, taking 99 Test wickets, including 36 in the 1920–21 Ashes ser ...

advised him to adopt a more conventional grip, but the 19th century Test bowler Charles Turner, known as "Terror Turner" and famous for his unorthodox ways, told O'Reilly to back his self-styled technique. O'Reilly decided to listen to Turner.McHarg, p. 41.

After taking a total of 3/88 in a Second XI match against Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, O'Reilly made his first-class debut in the 1927–28 season, playing in three matches and taking seven wickets. In his first match, against New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, O'Reilly took 2/37 and 1/53. He then played in what would be his only Sheffield Shield

The Sheffield Shield (currently known for sponsorship reasons as the Marsh Sheffield Shield) is the domestic first-class cricket competition of Australia. The tournament is contested between teams from the six states of Australia. Sheffield Sh ...

match for several years, going wicketless against Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, before returning figures of 4/35 against Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

.

Rural teaching post and absence from cricket

In 1928, O'Reilly was transferred by the New South Wales Education Department toGriffith, New South Wales

Griffith is a major regional city in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area that is located in the north-western part of the Riverina region of New South Wales, known commonly as the food bowl of Australia. It is also the seat of the City of Griffit ...

, an outback town in the south-west of the state, and he was unable to play first-class cricket. Over the next three years he moved around the country, including postings to Rylstone

Rylstone is a village and civil parish in the Craven district of North Yorkshire, England. It is situated very near to Cracoe and about 6 miles south west of Grassington. The population of the civil parish as of the 2011 census was 160.

...

and Kandos

Kandos is a small town in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, within Mid-Western Regional Council. The area is the traditional home of the Dabee tribe, of the Wiradjuri people. The town sits beneath Cumber Melon Mountain (fro ...

.

Teaching duties may have cost O'Reilly an early entry into Test cricket

Test cricket is a form of first-class cricket played at international level between teams representing full member countries of the International Cricket Council (ICC). A match consists of four innings (two per team) and is scheduled to last f ...

, as many young players were introduced in the 1928–29 home series against England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

following a large number of retirements of older players.

In the meantime, O'Reilly taught English to primary school children in Griffith, as well as singing—most of the pieces were Irish.McHarg, p. 42. At Rylstone he taught book-keeping and business, and he was promoted to the high school at Kandos. During this time he supplemented his income by travelling from town to town, playing in one-off cricket matches at the expense of the host's club. He worked on his bosie during the period and regularly dismissed outclassed opposition batsmen. O'Reilly regarded his cricketing isolation as highly beneficial as he regarded coaches to be ill-advised and detrimental to development.

Return to Sydney

In late 1930, O'Reilly was posted to Kogarah Intermediate High School in the southern Sydney suburb ofKogarah

Kogarah () is a suburb of Southern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Kogarah is located 14 kilometres (9 miles) south-west of the Sydney central business district and is considered to be the centre of the St George area.

Loca ...

, where he taught English, history, geography and business.McHarg, p. 46. O'Reilly resumed playing for North Sydney, confident that with an improved bosie, he was much more potent than before his rural teaching stint. As he only arrived back in Sydney in the second half of the 1930–31 season, O'Reilly was not considered for first-class selection, but he took 29 wickets at 14.72 for North Sydney.McHarg, p. 50.

In the 1931–32 season he emerged as the successor to Mailey in the New South Wales side. Within half a dozen games, he was one of several young players introduced to the Australian cricket team

The Australia men's national cricket team represents Australia in men's international cricket. As the joint oldest team in Test cricket history, playing in the first ever Test match in 1877, the team also plays One-Day International (ODI) a ...

for the Fourth Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

in a badly one-sided series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used in ...

against South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

. However, matters could have been rather different. O'Reilly had broken into the team for New South Wales' away matches against South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

and Victoria while the Test players were on international duty. He totaled only 2/81 in the first match and was then informed that he would be dropped after the second fixture. O'Reilly responded by bowling with a more attacking strategy, taking 5/22 and 2/112. At the end of the match, New South Wales' stand-in captain, the leg spinning all rounder

An all-rounder is a cricketer who regularly performs well at both batting and bowling. Although all bowlers must bat and quite a handful of batsmen do bowl occasionally, most players are skilled in only one of the two disciplines and are consi ...

Reginald Bettington, declared O'Reilly "the greatest bowler in the world", and although few agreed with this claim, Bettington made himself unavailable for selection so that O'Reilly would not be dropped. The reprieved leg spinner took a total of 8/204 in his next two matches, and while the figures were not overwhelming, they were enough to ensure a Test berth; with an unassailable 3–0 lead, the selectors wanted to blood new players.

O'Reilly took four wickets on his debut at the Adelaide Oval

Adelaide Oval is a sports ground in Adelaide, South Australia, located in the parklands between the city centre and North Adelaide. The venue is predominantly used for cricket and Australian rules football, but has also played host to rugby l ...

, two in each innings, supporting the senior leg-spinner, Clarrie Grimmett

Clarence Victor "Clarrie" Grimmett (25 December 1891 – 2 May 1980) was a New Zealand-born Australian cricketer. He is thought by many to be one of the finest early spin bowlers, and usually credited as the developer of the flipper.

Early l ...

, who took 14 wickets in the match and with Bradman scoring 299 not out

In cricket, a batter is not out if they come out to bat in an innings and have not been dismissed by the end of an innings. The batter is also ''not out'' while their innings is still in progress.

Occurrence

At least one batter is not out at ...

, Australia won the match. O'Reilly retained his place when the selectors kept the winning side for the final match of the Test series at the MCG. On a pitch made treacherous by rain, he did not bowl at all when South Africa were bowled out for just 36 in the first innings, and came on only towards the end of the second innings, when he took three wickets as the touring side subsided to 45 all out.Wisden (1933), pp. 661–665. He ended his first Test series with seven wickets at 24.85. In Sheffield Shield

The Sheffield Shield (currently known for sponsorship reasons as the Marsh Sheffield Shield) is the domestic first-class cricket competition of Australia. The tournament is contested between teams from the six states of Australia. Sheffield Sh ...

cricket in the 1931–32 season, O'Reilly took 25 wickets at an average

In ordinary language, an average is a single number taken as representative of a list of numbers, usually the sum of the numbers divided by how many numbers are in the list (the arithmetic mean). For example, the average of the numbers 2, 3, 4, 7 ...

of 21 runs per wicket, highlighted by his maiden ten-wicket haul

In cricket, a ten-wicket haul occurs when a bowler takes ten wickets in either a single innings or across both innings of a two-innings match. The phrase ten wickets in a match is also used.

Taking ten wickets in a match at Lord's earns the bowle ...

, 5/68 and 5/59 in a home match against South Australia after the Tests were over as New South Wales took out the title.McHarg, p. 56.

The following year he was more successful, taking 31 wickets at just 14 runs each. New South Wales won the competition in both seasons.

Test regular

O'Reilly became a regular member of the Australian Test side in the 1932–33 season and he played in all five Tests against

O'Reilly became a regular member of the Australian Test side in the 1932–33 season and he played in all five Tests against England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

in the infamous Bodyline

Bodyline, also known as fast leg theory bowling, was a cricketing tactic devised by the English cricket team for their 1932–33 Ashes tour of Australia. It was designed to combat the extraordinary batting skill of Australia's leading batsman ...

series. The Australian selectors perceived that O'Reilly would be their key bowler, and as he had never played against the English, omitted him from the early tour matches so that the tourists would not be able to decode his variations. As a result, he missed the Australian XI match against the Englishmen in Melbourne. In two Shield matches ahead of the Tests, he took 14 wickets, including a total of 9/66 in an innings win over Queensland. Although the national selectors had hidden him from the Englishmen, New South Wales declined to do so, and he played for his state a week ahead of the Tests. The hosts were bombarded with short-pitched bowling and heavily beaten by an innings; O'Reilly took 4/86 as the visitors amassed 530, dismissing leading English batsman Wally Hammond

Walter Reginald Hammond (19 June 1903 – 1 July 1965) was an English first-class cricketer who played for Gloucestershire in a career that lasted from 1920 to 1951. Beginning as a professional, he later became an amateur and was appointed cap ...

in the first of many battles between the pair.

The Tests started at the SCG and O'Reilly was the team's leading wicket-taker for the series with 27 wickets.Wisden (1934), p. 670. O'Reilly not only took most wickets but he also bowled by some distance the most over

Over may refer to:

Places

*Over, Cambridgeshire, England

* Over, Cheshire, England

* Over, South Gloucestershire, England

*Over, Tewkesbury, near Gloucester, England

**Over Bridge

* Over, Seevetal, Germany

Music

Albums

* ''Over'' (album), by P ...

s on either side, and he achieved a bowling economy of less than two runs from each of his 383 eight-ball overs. In the first match, he took 3/117 from 67 overs as England amassed 530 and took a ten-wicket victory. While his figures suggested that he bowled poorly—none of his wickets were those of batsmen—he beat the batsmen repeatedly. Between Tests, O'Reilly took 11 wickets in two Shield matches.

In the Second Test in Melbourne, O'Reilly opened the bowling as Australia opted to use only one pace bowler on a turning pitch.McHarg, p. 69. After Australia had made only 228, O'Reilly trapped Bob Wyatt

Robert Elliott Storey Wyatt (2 May 1901 – 20 April 1995) was an English cricketer who played for Warwickshire, Worcestershire and England in a career lasting nearly thirty years from 1923 to 1951. He was born at Milford Heath House in Surrey ...

leg before wicket

Leg before wicket (lbw) is one of the ways in which a batsman can be dismissed in the sport of cricket. Following an appeal by the fielding side, the umpire may rule a batter out lbw if the ball would have struck the wicket but was instead in ...

(lbw) before bowling both the Nawab of Pataudi and Maurice Leyland

Maurice Leyland (20 July 1900 – 1 January 1967) was an English international cricketer who played 41 Test matches between 1928 and 1938. In first-class cricket, he represented Yorkshire County Cricket Club between 1920 and 1946, scoring ove ...

to leave England at 4/98. He later took two tail-end wickets to end with 5/63 and secure Australia a first innings lead. Defending a target of 251, O'Reilly bowled the leading English opener Herbert Sutcliffe

Herbert Sutcliffe (24 November 1894 – 22 January 1978) was an English professional cricketer who represented Yorkshire and England as an opening batsman. Apart from one match in 1945, his first-class career spanned the period between the t ...

for 33 with a textbook perfect leg break that pitched on leg stump and clipped the top of the off stump. According to English team manager Plum Warner

Sir Pelham Francis Warner, (2 October 1873 – 30 January 1963), affectionately and better known as Plum Warner or "the Grand Old Man" of English cricket, was a Test cricketer and cricket administrator.

He was knighted for services to sport in ...

, Sutcliffe had never been defeated so comprehensively. O'Reilly also removed Hammond on the way to ending with 5/66 and securing a 111-run win. The ten-wicket haul was O'Reilly's first at Test level and the start of his strong career record over the English.McHarg, p. 69. However, Australia were not to taste further success. The controversial " fast leg theory" bowling used by England under newly appointed captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Douglas Jardine

Douglas Robert Jardine ( 1900 – 1958) was an English cricketer who played 22 Test matches for England, captaining the side in 15 of those matches between 1931 and 1934. A right-handed batsman, he is best known for captaining the English ...

brought the touring team victories in the last three matches: Australia were handicapped not only by the tactics, but also by a lack of quality fast bowlers

Fast bowling (also referred to as pace bowling) is one of two main approaches to bowling (cricket), bowling in the sport of cricket, the other being spin bowling. Practitioners of pace bowling are usually known as ''fast'' bowlers, ''quicks'', ...

; O'Reilly also opened the bowling in both the Third and Fourth Tests in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

and Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

respectively due to the selection of only one paceman. He was hindered by a decline in the form of Grimmett, who was dropped after the Third Test. O'Reilly took 2/83 and 4/79 in Adelaide, collecting the wicket of Sutcliffe for single figures in the first innings of a match overshadowed by near-riots after captain Bill Woodfull was struck in the heart. Australia were crushed by 338 runs, and lost the series in Brisbane. After O'Reilly had taken 4/101—including Sutcliffe and Jardine—in the first innings to keep Australia's first innings deficit to 16, the hosts collapsed to be 175 all out. O'Reilly took one wicket in the second innings of a six-wicket loss. The final Test in Sydney took a similar course; O'Reilly took 4/111 in the first innings including Sutcliffe and Jardine again, as the tourists took a 14-run lead before completing an eight-wicket win after another Australian collapse. O'Reilly was wicketless in the second innings and bowled 72 overs in total in the match. Reflecting on the performance of O'Reilly in the series, R Mason said "here we saw the first flexing of that most menacing genius".

In the 1933–34 season, with no Test series in Australia, O'Reilly finished top of the Sheffield Shield bowling averages, taking 33 wickets at an average of 18.30, but he had an inconsistent run. He started the season with 6/58 and 7/53 in an innings win over Queensland. After managing only three wickets across two consecutive testimonial matches, O'Reilly went wicketless against South Australia. He was angered by the subsequent comments in newspapers that he had already passed his zenith, and returned to form against Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

at the MCG. After claiming 3/92 in the first innings, he took 9/50 in the second innings.Wisden (1935), pp. 666–681. The nine wickets included six Test players, including leading batsmen Woodfull and Bill Ponsford

William Harold Ponsford MBE (19 October 1900 – 6 April 1991) was an Australian cricketer. Usually playing as an opening batsman, he formed a successful and long-lived partnership opening the batting for Victoria and Australia with Bill ...

.McHarg, p. 84. Given his heavy workload in the previous season, it was decided to keep O'Reilly fresh for the subsequent tour of England, so he played in only two of the last three matches, with a reduced bowling load, taking eight wickets.McHarg, p. 83. During the season, Bradman moved to North Sydney from St George Cricket Club

St George District Cricket Club is a cricket club based in the St. George area that competes in NSW Premier Cricket. The club's home ground is Hurstville Oval. Many famous Australian Test cricketers have represented the club.

Test players

...

to captain the team, and it was the only summer in which O'Reilly played alongside Bradman at grade level. The following year, O'Reilly moved to St George, which was near Kogarah, as they were obliged to play for a team in their area of residence.

O'Reilly was selected for the tour of England in 1934, where he and Grimmett were the bowling stars as Australia regained the Ashes

The Ashes is a Test cricket series played between England and Australia. The term originated in a satirical obituary published in a British newspaper, '' The Sporting Times'', immediately after Australia's 1882 victory at The Oval, its first ...

. They began by taking 19 of the 20 England wickets to fall in a comfortable victory in the First Test at Trent Bridge

Trent Bridge Cricket Ground is a cricket ground mostly used for Test, One-Day International and county cricket located in West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire, England, just across the River Trent from the city of Nottingham. Trent Bridge is also ...

. O'Reilly's match figures were 11 wickets for 129 runs, and taking seven for 54 in his second innings was to produce his best Test figures.

England then won the Second Test at Lord's

Lord's Cricket Ground, commonly known as Lord's, is a cricket venue in St John's Wood, London. Named after its founder, Thomas Lord, it is owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and is the home of Middlesex County Cricket Club, the England ...

, aided by the weather and Australia's inability to force the issue by avoiding the follow on. The hosts batted first and made 440, O'Reilly removing Walters. In reply, Australia were 2/192 when rain struck on the second evening and the sun turned the pitch into a sticky wicket

A sticky wicket (or sticky dog, or glue pot) is a metaphor used to describe a difficult circumstance. It originated as a term for difficult circumstances in the sport of cricket, caused by a damp and soft wicket.

In cricket

The phrase comes fr ...

the next day. When O'Reilly came in at 8/273, only 17 runs were needed to avoid the follow on, but he misjudged the flight of a Hedley Verity

Hedley Verity (18 May 1905 – 31 July 1943) was a professional cricketer who played for Yorkshire and England between 1930 and 1939. A slow left-arm orthodox bowler, he took 1,956 wickets in first-class cricket at an average of 14.90 ...

delivery and was bowled, thinking the ball to be fuller than it was and missing a lofted drive. Australia fell six runs short and were forced to bat again when the pitch was at its worst. They were bowled out again on the same afternoon as Verity took 14 wickets in a day. O'Reilly always regretted his dismissal, as he believed that if he had helped to avoid the follow on, he would have taken "six wickets without removing his waistcoat" and that Australia could have then chased the target in better conditions on the fourth day.McHarg, pp. 98–99.

O'Reilly shook English confidence in the Third Test, played on a placid surface at Old Trafford

Old Trafford () is a football stadium in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, and the home of Manchester United. With a capacity of 74,310 it is the largest club football stadium (and second-largest football stadium overall after Wembl ...

, by taking three wickets in four balls. Cyril Walters

Cyril Frederick Walters (28 August 1905 – 23 December 1992) was a Welsh first-class cricketer who had most of his success after leaving Glamorgan to do duty as captain-secretary of Worcestershire. In this role he developed his batting to such ...

, who up to that point had been untroubled, failed to pick the bosie and thus inside edged the ball to short leg.McHarg, p. 101. Bob Wyatt

Robert Elliott Storey Wyatt (2 May 1901 – 20 April 1995) was an English cricketer who played for Warwickshire, Worcestershire and England in a career lasting nearly thirty years from 1923 to 1951. He was born at Milford Heath House in Surrey ...

came in and was clean bowled for a golden duck, bringing Hammond in to face the hat-trick ball. The new batsman inside edged the ball past the stumps and through the legs of wicket-keeper Bert Oldfield

William Albert Stanley Oldfield (9 September 1894 – 10 August 1976) was an Australian cricketer and businessman. He played for New South Wales and Australia as a wicket-keeper. Oldfield's 52 stumpings during his Test career remains a record ...

, but the next delivery clean bowled him. This left England at 3/72, and O'Reilly removed Sutcliffe soon after, but the batsmen settled down and the next wicket did not come until Hendren fell just before the end of the first day's play. England were 5/355 and O'Reilly had taken each wicket. The next day, the hosts ended on 9/627, despite a relentless 59 overs from O'Reilly, who ended with 7/189 and was the only bowler to challenge the batsmen.McHarg, p. 102. The high-scoring match never looked likely to produce a result, except when Australia were in danger of being forced to follow on. They were 55 runs away from the follow on mark of 478 at the end of the third day with two wickets in hand, and O'Reilly was on one. The next day Arthur Chipperfield

Arthur Gordon Chipperfield (17 November 1905 – 29 July 1987) was an Australian cricketer who played in 14 Test matches between 1934 and 1938. He is one of only three players to make a score of 99 runs on his Test match debut.Headingley

Headingley is a suburb of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, approximately two miles out of the city centre, to the north west along the A660 road. Headingley is the location of the Beckett Park campus of Leeds Beckett University and Headingley ...

, with England saved by rain after a Bradman triple century, set up a match to decide the series at The Oval

The Oval, currently known for sponsorship reasons as the Kia Oval, is an international cricket ground in Kennington, located in the borough of Lambeth, in south London. The Oval has been the home ground of Surrey County Cricket Club since ...

. As the series was still alive, the match was timeless, rather than the customary five-day contest. After Australia made 701, O'Reilly took 2/93 to help dismiss the hosts for 321. The visitors then made 327 to set a target of 708 for victory. O'Reilly claimed 2/58, including Hammond, while Grimmett, with a total of eight wickets, proved the decisive bowler as Australia regained The Ashes with victory by 562 runs,McHarg, p. 105. which, more than 70 years on, is still the second largest margin of victory in terms of runs in any Test match.

O'Reilly was the leading Australian bowler of the tour, taking 28 Test wickets at an average of less than 25, while Grimmett took 25 wickets at just under 27 runs apiece. Australia's other Test bowlers took only 18 wickets between them. On the tour as a whole, O'Reilly headed the tourists' averages, with 109 wickets at 17.04, which meant that he also topped the averages for the whole English cricket season. In the matches against the English counties, he took 11 wickets in each of the games against Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire ...

and Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Mot ...

, and in the match against Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

, after Hans Ebeling

Hans Irvine Ebeling (1 January 1905 – 12 January 1980) was an Australian cricketer and cricket administrator.

Family

Ebeling's father, Arthur John Claus Frederick Ebeling (1863-1910), was of German descent. His mother was Mary Grace Ebeling ...

took the first wicket, he took the remaining nine for 38 runs, and that proved to be the best innings figures of his career. He was named as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year

The ''Wisden'' Cricketers of the Year are cricketers selected for the honour by the annual publication '' Wisden Cricketers' Almanack'', based primarily on their "influence on the previous English season". The award began in 1889 with the naming ...

in 1935 for his deeds on tour.

The tour ended with two non-first-class matches in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

against the hosts, and O'Reilly top-scored in a match for Australia for the only time, in the first of the two games. Having been allowed to open the innings after complaining about his lack of opportunities, he top-scored with 47 ahead of McCabe's 16.McHarg, p. 109. He found the tour to be a happy and healing experience after the acrimony of the Bodyline series.

O'Reilly played little state cricket for New South Wales in 1934–35; at the time, his first child was born and he took time off to ponder his future employment. He played in only one Shield match, against arch-rivals Victoria, and in the testimonial match for the retiring Woodfull and Ponsford. He took a total of eight wickets at 31.37 in these matches.

O'Reilly played no Shield cricket the following season, when he was selected for the Australian tour to South Africa. Although Bradman had been vice-captain under Woodfull in 1934, he did not travel to South Africa on grounds of ill health, but played a full domestic season despite this. The team was captained by Victor Richardson,McHarg, p. 114. and O'Reilly publicly described it as the happiest tour he had been on—he was one of several players who did not get along with Bradman.McHarg, p. 122.

The tour was another triumph for the leg-spin attack of O'Reilly and Grimmett, but O'Reilly was slightly overshadowed by his teammate in the Tests. With 44 wickets, Grimmett set a new record for the number of wickets by an Australian in a Test series, and he raised his Test career total to 216 wickets, beating the then world record of 189 by Englishman Sydney Barnes

Sydney Francis Barnes (19 April 1873 – 26 December 1967) was an English professional cricketer who is regarded as one of the greatest bowlers of all time. He was right-handed and bowled at a pace that varied from medium to fast-medium wit ...

. O'Reilly took 27 Test wickets at an average of just over 17 runs each: the other bowlers in the Australian team took 27 wickets between them. On the tour as a whole, O'Reilly came out ahead of Grimmett, with 95 wickets against Grimmett's 92, and an average of 13.56 against 14.80. O'Reilly also revealed hitherto undiscovered batting talents, making an undefeated 56 in the Fourth Test in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a Megacity#List of megacities, megacity, and is List of urban areas by p ...

, and putting on 69 for the last wicket with Ernie McCormick

Ernest Leslie McCormick (16 May 1906 – 28 June 1991) was an Australian cricketer who played in 12 Test matches from 1935 to 1938.

McCormick was an instrument-maker and jeweler. After the 1960–61 West Indies tour of Australia, Donald Bradm ...

. It was the only time in his first-class cricket

First-class cricket, along with List A cricket and Twenty20 cricket, is one of the highest-standard forms of cricket. A first-class match is one of three or more days' scheduled duration between two sides of eleven players each and is officiall ...

career that he passed 50. During the tour, O'Reilly developed his leg trap; the opening batsmen Jack Fingleton and Bill Brown were used in these positions.McHarg, p. 118.

Senior bowler

With Bradman's appointment as captain of the Australian team after the South African tour,

With Bradman's appointment as captain of the Australian team after the South African tour, Clarrie Grimmett

Clarence Victor "Clarrie" Grimmett (25 December 1891 – 2 May 1980) was a New Zealand-born Australian cricketer. He is thought by many to be one of the finest early spin bowlers, and usually credited as the developer of the flipper.

Early l ...

was dropped, leaving O'Reilly as the hub of the Australian bowling attack for the MCC Ashes tour in 1936–37.

O'Reilly was strongly aggrieved by the removal of his long-time bowling partner, and maintained that it was an "unpardonable" error that heavily weakened Australia's bowling attack. However, he remained vague about why he thought Grimmett had been removed, even though suspicion dogged Bradman.Piesse (2008), p. 166. Grimmett continued to dominate the wicket-taking on domestic cricket, while his replacements struggled in the international arena.

O'Reilly responded by becoming the leading Australian wicket-taker in the series taking 25, with Bill Voce

Bill Voce (8 August 1909 – 6 June 1984) was an English cricketer who played for Nottinghamshire and England. As a fast bowler, he was an instrumental part of England's infamous Bodyline strategy in their tour of Australia in 1932–1933 und ...

taking 26 for England. However, he almost failed to take to the field; O'Reilly and several players had threatened to withdraw after vice-captain Stan McCabe

Stanley Joseph McCabe (16 July 1910 – 25 August 1968) was an Australian cricketer who played 39 Test matches for Australia from 1930 to 1938. A short, stocky right-hander, McCabe was described by '' Wisden'' as "one of Australia's greatest ...

's wife was forbidden from sitting in the Members' Stand in the First Test. The Australian Board of Control backed down, but it was the start of a tumultuous season.

O'Reilly's wickets were at increased cost—his average increased to 22 runs per wicket—and he took five wickets in an innings only once, in the First Test at the 'Gabba in Brisbane, which England won convincingly. The circumstances of the series determined O'Reilly's role: after England won the first two Tests, O'Reilly appeared to have been given the job not just of bowling the opposition out, but also of containing them, and he was criticised in ''Wisden'' for defensive bowling. ''Wisden'' even went as far as to describe it as "leg theory". If the intention was to stifle England batsman Wally Hammond

Walter Reginald Hammond (19 June 1903 – 1 July 1965) was an English first-class cricketer who played for Gloucestershire in a career that lasted from 1920 to 1951. Beginning as a professional, he later became an amateur and was appointed cap ...

in particular, then it appears to have worked, but O'Reilly's figures for the series suggest he was consistent but not always penetrative. Morris Sievers

Morris William Sievers (13 April 1912 – 10 May 1968) was an Australian cricketer who played in three Test matches in 1936–37.

First-class career

Sievers began his career in 1930 for the Colts, at 17 years of age. Sievers was a useful rig ...

, from fewer matches, outperformed his average; Leslie Fleetwood-Smith, a slow left-arm spinner, got more eye-catching individual figures, including 10 wickets in the victory at Adelaide. Whatever the methods, they were successful: having lost the first two Tests, Australia proceeded to win the final three to retain The Ashes they had regained in England in 1934, and O'Reilly's five for 51 and three for 58 were the best figures in the decisive Fifth Test in Melbourne.

In the 1937–38 season, O'Reilly returned to more regular state cricket, and New South Wales duly won the Sheffield Shield for the first time in five seasons. He took 33 wickets at an average of just over 14 runs each, and against

In the 1937–38 season, O'Reilly returned to more regular state cricket, and New South Wales duly won the Sheffield Shield for the first time in five seasons. He took 33 wickets at an average of just over 14 runs each, and against South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

at Adelaide he repeated his feat against Somerset in 1934, taking the last nine wickets of the first innings at a cost of 41 runs. This time, he followed up with five for 57 in the second innings.

1938: Final tour of England

O'Reilly's second and final Ashes tour to England as a player in 1938 again saw him as the most effective bowler in the team. His final record of 22 wickets at an average of 27.72 in the four Tests—the Third Test was rained off without a ball being bowled—was marginally less than 1934, and in all matches he took 104 wickets at 16.59. In its report of the tour, however, ''Wisden''Trent Bridge

Trent Bridge Cricket Ground is a cricket ground mostly used for Test, One-Day International and county cricket located in West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire, England, just across the River Trent from the city of Nottingham. Trent Bridge is also ...

as England scored 8/658 and forced Australia to follow on and hold on for a draw.Harte, p. 377. In the Second Test at Lord's O'Reilly took 4/93 in the first innings and trapped Eddie Paynter

Edward Paynter (5 November 1901 – 5 February 1979) was an English cricketer: an attacking batsman and excellent fielder. His Test batting average of 59.23 is the seventh highest of all time, and second only to Herbert Sutcliffe amongst English ...

for 99 to end a 222-run partnership with Hammond. In reply to England's 494, Australia were in danger of being forced to follow on; O'Reilly came in and made 42, featuring in a partnership of 85 in only 46 minutes with Bill Brown that enabled Australia to save the match: having been dropped by Paynter, he hit Hedley Verity

Hedley Verity (18 May 1905 – 31 July 1943) was a professional cricketer who played for Yorkshire and England between 1930 and 1939. A slow left-arm orthodox bowler, he took 1,956 wickets in first-class cricket at an average of 14.90 ...

for consecutive sixes to take Australia past the follow-on

In the game of cricket, a team who batted second and scored significantly fewer runs than the team who batted first may be forced to follow-on: to take their second innings immediately after their first. The follow-on can be enforced by the team ...

mark. Brown recalled "It was a nice day, and a nice wicket. O'Reilly came in, and I told him I'd take the quicks— Wellard and Farnes—and Tiger 'Reillytook Verity." Australia reached 422 and O'Reilly took 2/53 in the second innings as the match petered into a draw.

In an otherwise high-scoring series, O'Reilly's greatest triumph was in the low-scoring Fourth Test at Headingley

Headingley is a suburb of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, approximately two miles out of the city centre, to the north west along the A660 road. Headingley is the location of the Beckett Park campus of Leeds Beckett University and Headingley ...

, where he exploited a difficult pitch to take five wickets in each innings as Australia secured the victory that enabled them to retain the Ashes.Harte, p. 378. With the series level at 0–0, England captain Hammond elected to bat first; O'Reilly's 5/66 was largely responsible for ending England's innings at 223. He removed Hammond, who had top-scored with 76, Bill Edrich

William John Edrich (26 March 1916 – 24 April 1986) was a first-class cricketer who played for Middlesex, Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), Norfolk and England.

Edrich's three brothers, Brian, Eric and Geoff, and also his cousin, John, all pla ...

and Denis Compton

Denis Charles Scott Compton (23 May 1918 – 23 April 1997) was an English multi-sportsman. As a cricketer he played in 78 Test matches and spent his whole cricket career with Middlesex. As a footballer, he played as a winger and spent most o ...

, all bowled in quick succession.Harte, p. 378.Whitington, p. 254. England were 1/73 on the third day, an overall lead of 54, when O'Reilly began a new spell after Bradman had switched his ends. Joe Hardstaff junior

Joseph Hardstaff Jr (3 July 1911 – 1 January 1990) was an English cricketer, who played in twenty three Test matches for England from 1935 to 1948. Hardstaff's father, Joe senior played for Nottinghamshire and England and his son, also nam ...

hooked him for four and the next ball was no-ball

In cricket, a no-ball is a type of illegal delivery to a batter (the other type being a wide). It is also a type of extra, being the run awarded to the batting team as a consequence of the illegal delivery. For most cricket games, especially a ...

ed by the umpire. O'Reilly was reported to have become visibly enraged;Whitington, p. 256. he bowled Hardstaff next ball and then removed Hammond for a golden duck. This precipitated an English collapse to 123 all out, and O'Reilly ended with 5/56 and a total of 10/122. O'Reilly effort proved to be crucial as Australia scraped home by five wickets just 30 minutes before black clouds brought heavy rain, which would have made batting treacherous. The victory ensured the retention of the Ashes, and O'Reilly ranked it as his finest performance, alongside his ten wickets in the Second Bodyline Test of 1932–33.

Australia had retained the Ashes, but England struck back at The Oval, where they posted the then-record Test score of 7/903. Early on, O'Reilly trapped Edrich lbw for 12, to secure his 100th Test wicket against England. In a timeless match, Len Hutton

Sir Leonard Hutton (23 June 1916 – 6 September 1990) was an English cricketer. He played as an opening batsman for Yorkshire County Cricket Club from 1934 to 1955 and for England in 79 Test matches between 1937 and 1955. '' Wisden Cricke ...

made a world record Test score of 364 in a fastidious and watchful innings of 13 hours, surpassing Bradman's 334. When he was on 333, O'Reilly deliberately bowled two no-balls in an attempt to break Hutton's concentration by tempting him to hit out, but the Englishman blocked them with a straight bat.

O'Reilly eventually removed Hutton and ended with 3/178 off 85 overs. Nevertheless, these compared favourably with Fleetwood-Smith's 1/298 off 87 overs. O'Reilly was the only Australian to take more than a solitary wicket,Whitington, p. 257. and rated Hutton's knock as the finest innings played against him. Australia collapsed to lose by an innings and 579 runs,Harte, p. 379. the heaviest defeat in Test history. O'Reilly's lack of success went with The Oval Test in 1934, when he took a total of 4/151.

O'Reilly scaled back his participation in Sheffield Shield cricket in the 1938–39 season, making himself unavailable for most of the campaign to spend time with his newborn son after half a year in England; he played in only two matches, against South Australia and arch-rivals Victoria. He took a ten-wicket haul in the latter match, but his figures of 6/152 and 4/60 were not enough to prevent defeat. Both teams were at full strength and eight of O'Reilly's victims were Test players, including batsman Lindsay Hassett

Arthur Lindsay Hassett (28 August 1913 – 16 June 1993) was an Australian cricketer who played for Victoria and the Australian national team. The diminutive Hassett was an elegant middle-order batsman, described by '' Wisden'' as, "... a mas ...

twice. O'Reilly's only other match was for Bradman's XI against Rigg's XI in a match to commemorate the centenary of the Melbourne Cricket Club

The Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC) is a sports club based in Melbourne, Australia. It was founded in 1838 and is one of the oldest sports clubs in Australia.

The MCC is responsible for management and development of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, ...

, in which he took a total of 7/129, to end the season with 19 wickets at 23.16.Whitington, p. 258.

He resumed regular service for New South Wales in the next season, taking 55 wickets at 15.12 in seven matches.Whitington, p. 259. He took 8/23 and 6/22 to set up an innings win over Queensland and 6/77 and 4/62 in another victory over South Australia. The two matches against Victoria were shared as O'Reilly took 17 wickets. In the second of the matches, in Sydney, Hassett became the only person to score centuries in both innings of match involving O'Reilly. Despite Hassett's feat, New South Wales won the match; O'Reilly took a total of 8/157.