Bethany Veney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bethany Veney (c. 1812–1815 – November 16, 1915), born into slavery on a farm near Luray, Virginia as Bethany Johnson, whose autobiography, ''Aunt Betty's Story: The Narrative of Bethany Veney, A Slave Woman'' was published in 1889. She married twice, first to an enslaved man, Jerry Fickland, with whom she had a daughter, Charlotte. He was sold away from her and she was later married to Frank Veney, a free black man. She was sold on an auction block to her employer,

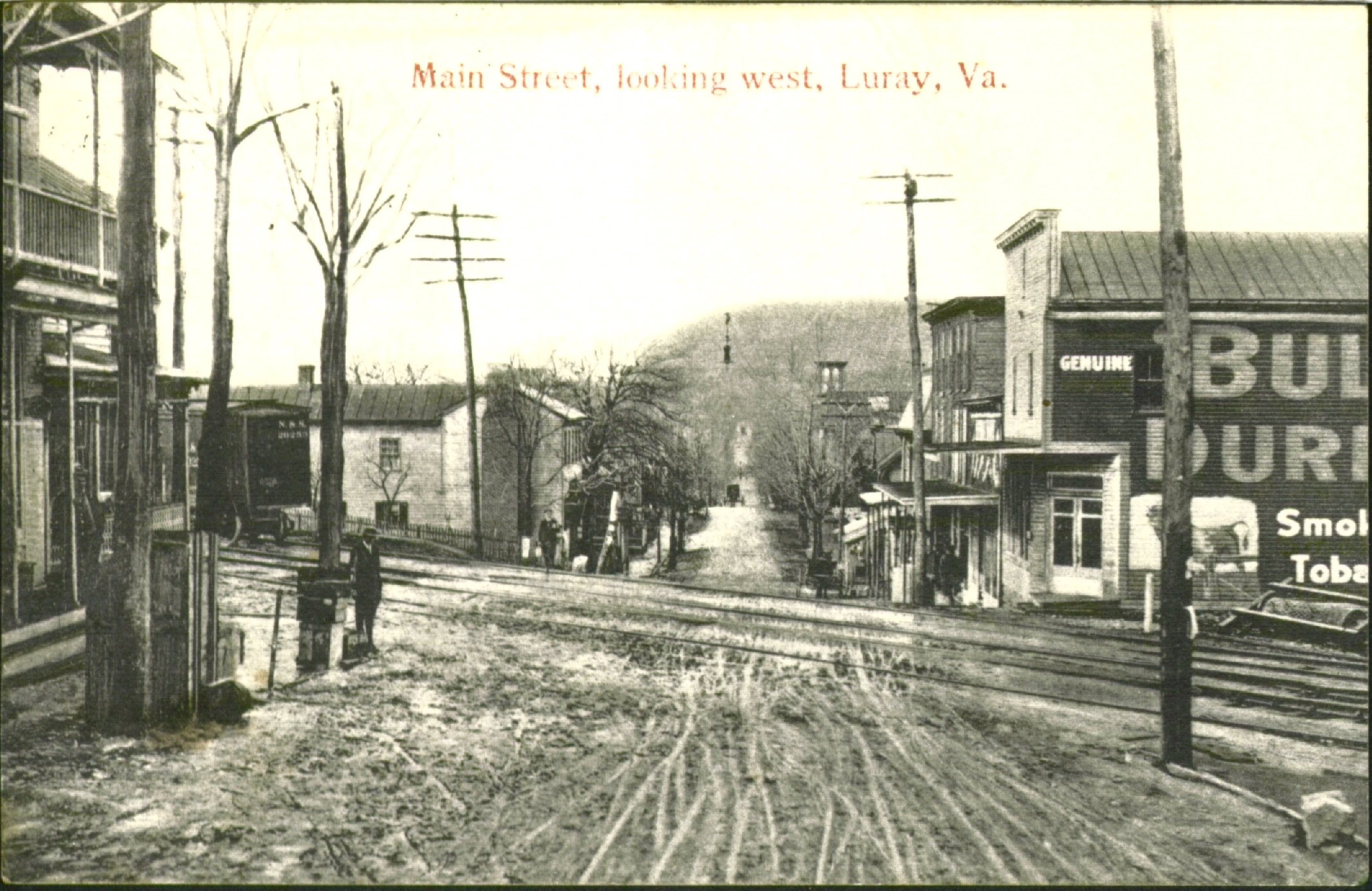

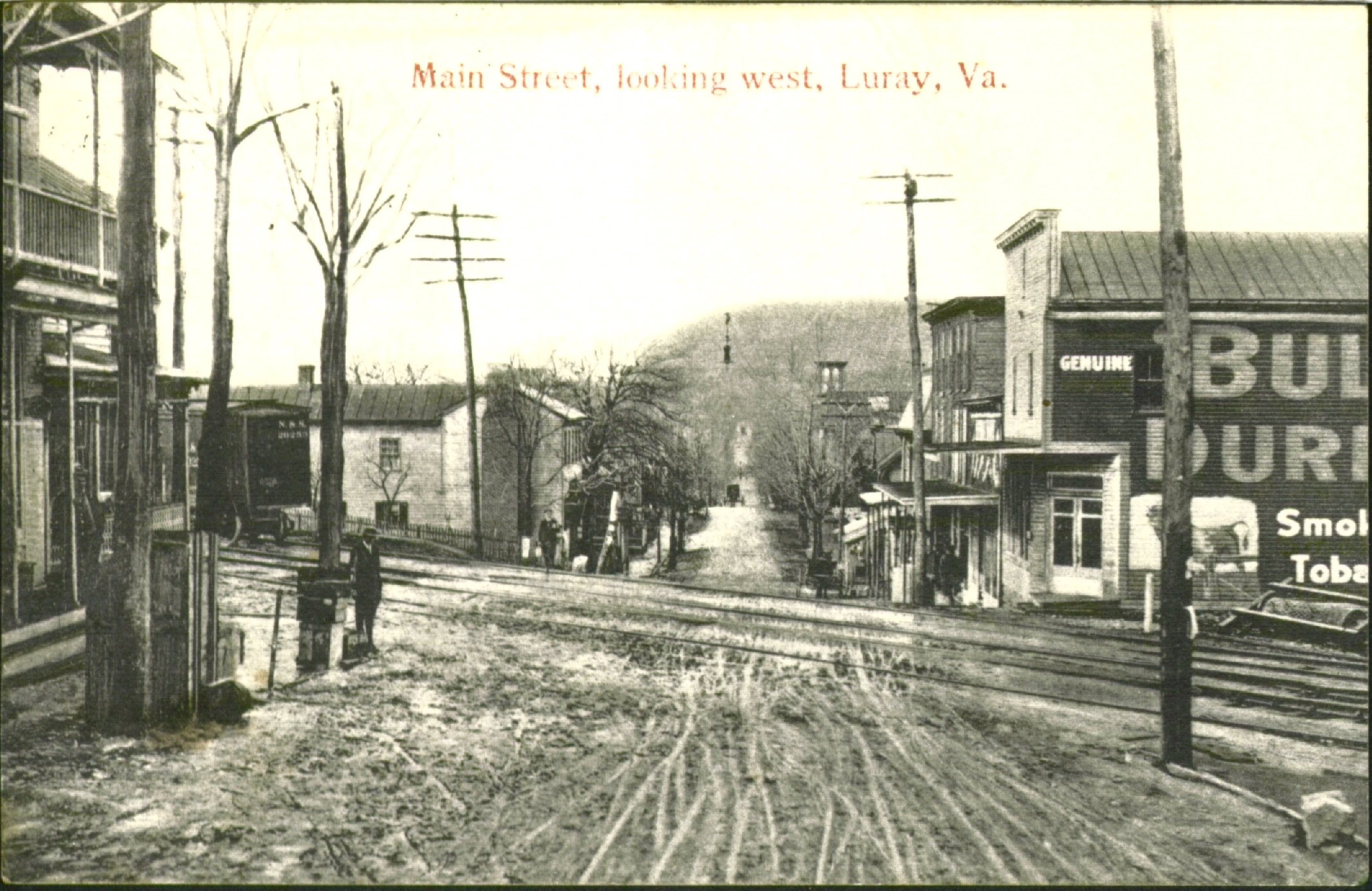

Around 1815, Bethany Johnson was born into slavery on the Pass Run farm, near

Around 1815, Bethany Johnson was born into slavery on the Pass Run farm, near

Owned by the indebted Jonas Mannyfield (also spelled Menefee), Fickland was taken to Little Washington, Virginia slave pen where he was to be auctioned around March 1843. Veney was given permission to go to see her husband, she traveled more than a day to meet up with Fickland's mother and they went together to the slave pen where Fickland and the rest of Mannyfield's slaves were held. Slave trader Frank White bought the enslaved people with the intention of selling them in the

Owned by the indebted Jonas Mannyfield (also spelled Menefee), Fickland was taken to Little Washington, Virginia slave pen where he was to be auctioned around March 1843. Veney was given permission to go to see her husband, she traveled more than a day to meet up with Fickland's mother and they went together to the slave pen where Fickland and the rest of Mannyfield's slaves were held. Slave trader Frank White bought the enslaved people with the intention of selling them in the  At Veney's request, she and her daughter were sold to John Printz Sr. of Luray. She worked for his family until the early 1850s when she was sold to McCoy and his partner John O'Neile. Her daughter remained with the Printz family. When she realized that she was about to be sold, she asked a white person from church to purchase her, but she was declined. She was brought to the slave auction in

At Veney's request, she and her daughter were sold to John Printz Sr. of Luray. She worked for his family until the early 1850s when she was sold to McCoy and his partner John O'Neile. Her daughter remained with the Printz family. When she realized that she was about to be sold, she asked a white person from church to purchase her, but she was declined. She was brought to the slave auction in

Veney made arrangements with David McCoy and John Printz that allowed her to rent a house from Pritz on Stony Man, a mountain spur south of Luray. She supported herself and her son by keeping wages early by being hired out, and paying a $30 annual free to McCoy for his share of her earnings.

In the late 1850s, Veney was hired for $1.50 per week as a cook and housekeeper for copper mining speculators—

Veney made arrangements with David McCoy and John Printz that allowed her to rent a house from Pritz on Stony Man, a mountain spur south of Luray. She supported herself and her son by keeping wages early by being hired out, and paying a $30 annual free to McCoy for his share of her earnings.

In the late 1850s, Veney was hired for $1.50 per week as a cook and housekeeper for copper mining speculators—

''From Bondage to Belonging: the Worcester slave narratives''

University of Massachusetts Press. . *Moore, Robert H., II, "Clarifying a few details in the narrative of Bethany Veney," '' The Page News and Courier'' (Luray, Virginia), August 24, 2000. *Moore, Robert H., II, "Frank Veney – The Other Half of the Bethany Veney Story," ''The Page News and Courier'', July 1, 2004. *Moore, Robert H., II, "What Happened to Bethany Veney after Leaving Page County? Parts 1 – 2", ''The Page News and Courier'', March 30, 2006, and April 6, 2006.

''A Moment in Worcester Black History - Bethany Veney''

(YouTube video) {{DEFAULTSORT:Veney, Bethany 1810s births 1915 deaths American centenarians African-American centenarians 19th-century American slaves People from Luray, Virginia Writers from Virginia People who wrote slave narratives American memoirists American non-fiction writers American women memoirists Women centenarians 20th-century African-American people 20th-century African-American women 19th-century African-American women

George J. Adams

George Jones Adams (ca. 1811 – May 11, 1880) was the leader of a schismatic Latter Day Saint sect who led an ill-fated effort to establish a colony of Americans in Palestine. Adams was also briefly a member of the First Presidency in the Chur ...

. He brought her to Providence, Rhode Island followed by Worcester, Massachusetts. After the Civil War, Veney made four trips to Virginia to move her daughter and her family and 16 additional family members north to New England.

Early life

Around 1815, Bethany Johnson was born into slavery on the Pass Run farm, near

Around 1815, Bethany Johnson was born into slavery on the Pass Run farm, near Luray Luray may refer to:

* Luray, Eure-et-Loir, a commune in the Eure-et-Loir ''département'', France

* Luray, Indiana

* Luray, Kansas

* Luray, Missouri

* Luray, Ohio

* Luray, South Carolina

Luray is a town in Hampton County, South Carolina, United ...

, in what is now Page County, Virginia. Her parents, Charlotte and Joseph Johnson, had five children, including Matilda and Stephen. Veney was of African American and Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

heritage. She was owned by James Fletcher, who owned Pass Run. Fletcher's daughter Nasenith taught her a fire and brimstone lesson about the repercussions of lying, which was softened by her mother's lesson about the rewards of being truthful. The lesson about honesty had a life-long impact that helped her fight for herself.

Occasionally, Fletcher called on Veney to sing and dance for his visitors. Her mother died when she was about nine years of age and she did not know her father. Soon after her mother's death, Fletcher died. The enslaved people that he held were left to his five daughters and two sons, which split up her family. Lucy Fletcher, who Veney considered to be kindhearted, received her and her sister Matilda. Lucy was unmarried and she and her slaves moved in with her sister Nasenith Fletcher and David Kibbler, after they were married on January 25, 1827. For a period of time, Veney was hired out to a woman who fed and clothed her in exchange for her labor. She considered her kind, because she had been given enough food to survive and was not whipped. Veney remarked that white children not born into slavery would have a different definition of kindness. David Kibler was a cruel master who was violent towards all the slaves in his household. She was once whipped with a nail rod that made her lame, and then was whipped again after her mistress inquired about the cause of her injury and asked Kibbler about it. One time when she was told to go cut a switch to be beaten with, she ran away from the unjustice of the beating, and after a night of a heavy rain, she sought assistance from Kibbler's father, who was also a slave owner who beat his slaves. Once he heard her story, he and Veney visited Kibbler, who was told by his father not to whip her. She returned to Kibbler's house and was not beaten.

Religion

Kibbler's brother Jerry and sister Sally were converted Methodists, who found religion after attending a camp meeting. They outfitted a school house building in Luray to also serve as a venue for church services and revival meetings and encouraged Veney to become a Christian. Lucy arranged for someone to take Veney to a camp meeting, where she was inspired by a hymn. She began to pray for her freedom, believing that if she was a good Christian her dream would come true. Veney often thought of how nice it would be to earn her own money and to save it until she could afford a house with a lovely garden. She relied on her faith to take her through difficult times throughout her life. Still a young girl, she was severely punished by her slaveholder for attending church. She continued to go to church during the times that she was hired out to Mr. Levers and after she got before Kibbler and begged to be allowed to attend church. He said, "Well, I'll go the devil if you ain't my match. Yes, go to meeting..." From that point forward, she was able to attend church. She became known for her honesty and devotion.Marriage and children

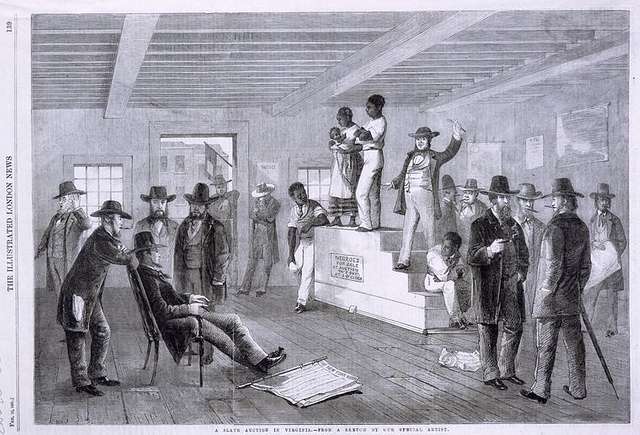

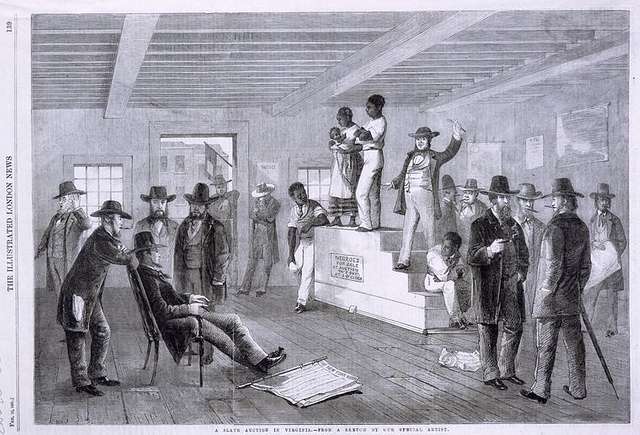

Around the late 1830s, Bethany Johnson married Jerry Fickland, an enslaved man who lived seven miles from her on the other side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They received permission to marry from their owners and they had a simple wedding ceremony. Knowing that they could be separated at any time by their owners, they excluded promises to be true, and forsaking all others. They continued to live at the plantations of their owners, and could only visit one another when they were given permission and received a pass to travel on the roads without being picked up as runaways. Owned by the indebted Jonas Mannyfield (also spelled Menefee), Fickland was taken to Little Washington, Virginia slave pen where he was to be auctioned around March 1843. Veney was given permission to go to see her husband, she traveled more than a day to meet up with Fickland's mother and they went together to the slave pen where Fickland and the rest of Mannyfield's slaves were held. Slave trader Frank White bought the enslaved people with the intention of selling them in the

Owned by the indebted Jonas Mannyfield (also spelled Menefee), Fickland was taken to Little Washington, Virginia slave pen where he was to be auctioned around March 1843. Veney was given permission to go to see her husband, she traveled more than a day to meet up with Fickland's mother and they went together to the slave pen where Fickland and the rest of Mannyfield's slaves were held. Slave trader Frank White bought the enslaved people with the intention of selling them in the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

. Fickland was sent by White to get his wife, with the promise that they would be kept together. Realizing that they would not likely be kept together, and that they would suffer in the harsh cotton fields and rice swamps further south, Fickland fled for the mountains. He was ultimately captured by slave trader David McCoy. Veney never saw him again. Their daughter, Charlotte E. Fickland, was born in January 1844. She was named after Veney's mother. Realizing that her daughter would be subject to owner's sexual abuse, without a means of redress, she said of her feelings from that time,

At Veney's request, she and her daughter were sold to John Printz Sr. of Luray. She worked for his family until the early 1850s when she was sold to McCoy and his partner John O'Neile. Her daughter remained with the Printz family. When she realized that she was about to be sold, she asked a white person from church to purchase her, but she was declined. She was brought to the slave auction in

At Veney's request, she and her daughter were sold to John Printz Sr. of Luray. She worked for his family until the early 1850s when she was sold to McCoy and his partner John O'Neile. Her daughter remained with the Printz family. When she realized that she was about to be sold, she asked a white person from church to purchase her, but she was declined. She was brought to the slave auction in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, and she pretended to be sick by putting baking soda in her mouth before bidding began. She foamed at the mouth and no sale was made. Veney worked in the McCoy household and was hired out, in which case she paid McCoy $20 a year and kept the rest of her earnings. She was able to visit her daughter periodically.

She married a free black man, Frank Veney, becoming Bethany Veney. Frank built roads for McCoy. Veney met Frank when she was a cook for the road construction crew. The had a son named Joe.

Stony Man

Veney made arrangements with David McCoy and John Printz that allowed her to rent a house from Pritz on Stony Man, a mountain spur south of Luray. She supported herself and her son by keeping wages early by being hired out, and paying a $30 annual free to McCoy for his share of her earnings.

In the late 1850s, Veney was hired for $1.50 per week as a cook and housekeeper for copper mining speculators—

Veney made arrangements with David McCoy and John Printz that allowed her to rent a house from Pritz on Stony Man, a mountain spur south of Luray. She supported herself and her son by keeping wages early by being hired out, and paying a $30 annual free to McCoy for his share of her earnings.

In the late 1850s, Veney was hired for $1.50 per week as a cook and housekeeper for copper mining speculators—George J. Adams

George Jones Adams (ca. 1811 – May 11, 1880) was the leader of a schismatic Latter Day Saint sect who led an ill-fated effort to establish a colony of Americans in Palestine. Adams was also briefly a member of the First Presidency in the Chur ...

and J. Butterworth, of Providence, Rhode Island—who reopened a mine near Stony Man Mountain

Stony Man Mountain, also known as Stony Man, is a mountain in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia and is the most northerly 4,000 foot peak in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Its maximum elevation is 4,011 feet or 1,223 meters above sea level with a clean ...

. McCoy's property was seized and auctioned due to his gambling debts. On December 27, 1858, Adams purchased Veney and her son Joe for $775 ().

New England

Adams moved Veney and her son to Providence in August 1859, and both were freed by Adams. Veney supported herself by taking in laundry and selling bluing door-to-door. Her son Joe died of an illness late that year. Living in New England, she was separated from her daughter, son-in-law, and husband. Frank Veney went on to marry another women after three years had passed. Frank claimed that Veney was his ninth of twenty-five wives in an article published by the ''Page News and Courier'' in 1915. It was too dangerous for a lone Black woman to travel to Virginia to visit her family followingJohn Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

(October 1859) and the commencement of the Civil War (1861–1865).

Veney worked for the Adams family in Providence, and then moved with then to Worcester, Massachusetts in 1860. Before the war, she made large pots of gruel that she brought out to the camps of the Worcester Volunteers. She continued to sell bluing and take in washing in Massachusetts. Feeling comfortable there, knowing that she was safe from being sold on auction blocks, she remained in Worcester after the Adams' family returned to Providence. Veney joined the Park Street Methodist Church, a white church, and was a founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Bethel Church in 1867, and was a prominent member of the church. For more than 50 years, she walked to the Sterling Camp Meeting Grounds The Sterling Camp Meeting Grounds, also known at the Worcester Methodist District Camp was a Methodist camp ground founded in 1852 that was located south of the East and West Waushacum Ponds and two miles south of Sterling, Massachusetts. The 14-mil ...

in Sterling, Massachusetts, a nearly 12-mile walk from her house that is estimated to take about 4 hours one-way.

After the end of the Civil War, Veney collected family members that she missed dearly and moved them to New England. She started with her daughter, son-in-law Aaron Jackson, and grandchild, who lived adjacent to her, and then made three more trips to move 16 more relatives north. While in the Luray, Virginia area, she also met up with three of her former owners, McCoy, Printz, and Kibbler. She was grateful to be on the other side of suffering that she endured for years and to be reunited with her family. In Worcester, she purchased a house for herself at 21 Winfield Street and other houses for her extended family.

''Narrative of Bethany Veney, a Slave Woman''

In 1889, the ''Narrative of Bethany Veney, a Slave Woman'' was published. It was dictated to a white woman with the initials M. W. G. The narrative documents her life as an enslaved child and woman. She describes her religious conversion and the role that religion played in her life. Her narrative includes two letters from two ministers, Rev. Erastus Spaulding of Millbury and the Rev. V.A. Cooper. One of them describes Veney's strength of character and the other focuses on the sinfulness of slavery. Veney also describes her life in the North after attaining her freedom. Jared Silverstein, author of ''The Faith of a Woman: a Slave Narrative of Love, Despair, and Atonement'' said, "Her short yet powerful narrative reveals how her unremitting faith in God empowered her to navigate the most trying of circumstances, from childhood as a slave to adulthood as a woman fighting for her freedom." Veney had a unique approach to writing her narrative. She shared her story of humanity, focusing on her heartaches and the morals that she lived by, rather than documenting all the ways in which slavery was horrible.Later years and death

Veney remained active throughout her life. She died at her daughter's house in Worcester on November 16, 1915 and was buried atHope Cemetery

Hope Cemetery is a rural cemetery in Barre, Vermont. The city calls itself the "Granite Capital of the World", and the cemetery is known for the superb granite craftsmanship on its memorials and tombstones. Barre is also home to the world's la ...

in the same city. Beside her is her daughter Charlotte who died February 14, 1921.

Legacy

On July 12, 2003, the Governor of Massachusetts,Mitt Romney

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American politician, businessman, and lawyer serving as the junior United States senator from Utah since January 2019, succeeding Orrin Hatch. He served as the 70th governor of Massachusetts f ...

, signed a proclamation honoring Bethany Veney and her life by declaring the day "Bethany Veney Day in Worcester, Massachusetts".

In ''Collected Black Women's Narratives'', Anthony Gerard recognized Veney—along with Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor (August 6, 1848 – October 6, 1912) is known for being the first Black nurse during the American Civil War. Beyond just her aptitude in nursing the wounded of the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Taylor was the f ...

, Nancy Prince, and Louisa Picquet

Louisa Picquet (c. 1829, Columbia, South Carolina – August 11, 1896, New Richmond, Ohio) was an African American born into slavery. Her slave narrative, ''Louisa Picquet, the Octoroon, or, Inside Views of Southern Domestic Life,'' was published ...

—as a "woman hostrove to maintain her dignity and independence in an increasingly violent and consistently racist America." He further states that her narrative documents "Veney's experiences in slavery and in freedom and her spiritual growth throughout her life" and "revealed her defiance, ingenuity, fortitude, and independence. In the inhuman grip of chattel slavery, Veney continually demonstrates her humanity..."

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * *Further reading

*McCarthy, B. Eugene; Doughton, Thomas L. (2007)''From Bondage to Belonging: the Worcester slave narratives''

University of Massachusetts Press. . *Moore, Robert H., II, "Clarifying a few details in the narrative of Bethany Veney," '' The Page News and Courier'' (Luray, Virginia), August 24, 2000. *Moore, Robert H., II, "Frank Veney – The Other Half of the Bethany Veney Story," ''The Page News and Courier'', July 1, 2004. *Moore, Robert H., II, "What Happened to Bethany Veney after Leaving Page County? Parts 1 – 2", ''The Page News and Courier'', March 30, 2006, and April 6, 2006.

External links

''A Moment in Worcester Black History - Bethany Veney''

(YouTube video) {{DEFAULTSORT:Veney, Bethany 1810s births 1915 deaths American centenarians African-American centenarians 19th-century American slaves People from Luray, Virginia Writers from Virginia People who wrote slave narratives American memoirists American non-fiction writers American women memoirists Women centenarians 20th-century African-American people 20th-century African-American women 19th-century African-American women