Bertrand Russell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bertrand Russell was opposed to war from a young age; his opposition to World War I being used as grounds for his dismissal from Trinity College at Cambridge. This incident fused two of his most controversial causes, as he had failed to be granted Fellow status which would have protected him from firing, because he was not willing to either pretend to be a devout Christian, or at least avoid admitting he was agnostic.

He later described the resolution of these issues as essential to freedom of thought and expression, citing the incident in Free Thought and Official Propaganda, where he explained that the expression of any idea, even the most obviously "bad", must be protected not only from direct State intervention, but also economic leveraging and other means of being silenced:

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in political causes primarily related to

Bertrand Russell was opposed to war from a young age; his opposition to World War I being used as grounds for his dismissal from Trinity College at Cambridge. This incident fused two of his most controversial causes, as he had failed to be granted Fellow status which would have protected him from firing, because he was not willing to either pretend to be a devout Christian, or at least avoid admitting he was agnostic.

He later described the resolution of these issues as essential to freedom of thought and expression, citing the incident in Free Thought and Official Propaganda, where he explained that the expression of any idea, even the most obviously "bad", must be protected not only from direct State intervention, but also economic leveraging and other means of being silenced:

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in political causes primarily related to

In June 1955, Russell had leased Plas Penrhyn in

In June 1955, Russell had leased Plas Penrhyn in  Russell published his three-volume autobiography in 1967, 1968, and 1969. He made a cameo appearance playing himself in the anti-war

Russell published his three-volume autobiography in 1967, 1968, and 1969. He made a cameo appearance playing himself in the anti-war

at probatesearch.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 August 2015. In 1980, a memorial to Russell was commissioned by a committee including the philosopher A. J. Ayer. It consists of a bust of Russell in Red Lion Square in London sculpted by Marcelle Quinton. Lady Katharine Jane Tait, Russell's daughter, founded the Bertrand Russell Society in 1974 to preserve and understand his work. It publishes the ''Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin'', holds meetings and awards prizes for scholarship, including the Bertrand Russell Society Award. She also authored several essays about her father; as well as a book, ''My Father, Bertrand Russell'', which was published in 1975. All members receive ''Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies''. For the sesquicentennial of his birth, in May 2022, McMaster University's Bertrand Russell Archive, the university’s largest and most heavily used research collection, organized both a physical and virtual exhibition on Russell’s anti-nuclear stance in the post-war era

''Scientists'' ''for Peace: the Russell-Einstein Manifesto and the Pugwash Conference''

which included the earliest version of the

Bertrand Russell: Philosopher and Humanist

', London: Lawerence & Wishart, 1968 *Ray Monk. ''Bertrand Russell: Mathematics: Dreams and Nightmares'', London: Phoenix, 1997, *Ray Monk. ''Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude, 1872–1920'' Vol. I, New York: Routledge, 1997, *Ray Monk. ''Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness, 1921–1970'' Vol. II, New York: Routledge, 2001, *Caroline Moorehead. ''Bertrand Russell: A Life'', New York: Viking, 1993, *George Santayana. "Bertrand Russell", in ''Selected Writings of George Santayana'', Norman Henfrey (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, I, 1968, pp. 326–329 *Peter Stone et al.

Bertrand Russell's Life and Legacy

'. Wilmington: Vernon Press, 2017. *Katharine Tait. ''My Father Bertrand Russell'', New York: Thoemmes Press, 1975 *Alan Wood. ''Bertrand Russell: The Passionate Sceptic'', London: George Allen & Unwin, 1957.

Bertrand Russell – media

on YouTube

at McMaster University

The Bertrand Russell Society

*

BBC ''Face to Face'' interview

with Bertrand Russell and John Freeman (British politician), John Freeman, broadcast 4 March 1959 * including the Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1950 "What Desires Are Politically Important?"

Interview with Ray Monk

at Today (BBC Radio 4), ''Today'', 18 May 2022 (from 2:58:35) {{DEFAULTSORT:Russell, Bertrand Bertrand Russell, 1872 births 1970 deaths 19th-century atheists 19th-century English mathematicians 19th-century English philosophers 19th-century essayists 20th-century atheists 20th-century English mathematicians 20th-century English philosophers 20th-century essayists Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Analytic philosophers Anti–Vietnam War activists Aristotelian philosophers Atheist philosophers British anti–nuclear weapons activists British anti–World War I activists British atheism activists British cultural critics British ethicists British Nobel laureates Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament activists British consciousness researchers and theorists Consequentialists Critics of Christianity Critics of religions Critics of the Catholic Church Critics of work and the work ethic De Morgan Medallists Deaths from influenza Earls Russell Empiricists English agnostics English anti-fascists English anti–nuclear weapons activists English atheist writers English essayists English historians of philosophy English humanists English logicians English male non-fiction writers English Nobel laureates English pacifists English people of Scottish descent English people of Welsh descent English political commentators English political philosophers English political writers English prisoners and detainees English sceptics English social commentators English socialists Epistemologists European democratic socialists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Founders of philosophical traditions Free love advocates Free speech activists Freethought writers Georgists Honorary Fellows of the British Academy Infectious disease deaths in Wales Intellectual historians Jerusalem Prize recipients Kalinga Prize recipients LGBT rights activists from England Liberal socialism Linguistic turn Logicians Mathematical logicians Members of the Order of Merit Metaphilosophers Metaphysicians Metaphysics writers Moral philosophers Nobel laureates in Literature Nonviolence advocates Ontologists People from Harting People from Monmouthshire Philosophers of culture Philosophers of economics Philosophers of education Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of law Philosophers of literature Philosophers of logic Philosophers of love Philosophers of mathematics Philosophers of mind Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Philosophers of sexuality Philosophers of social science Philosophers of technology Philosophers of war Political philosophers Presidents of the Aristotelian Society Residents of Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park Rhetoric theorists Russell family, Bertrand Russell Secular humanists Set theorists Social critics The Nation (U.S. magazine) people Theorists on Western civilization Universal basic income writers University of California, Los Angeles faculty University of Chicago faculty Utilitarians Writers about activism and social change Writers about communism Writers about globalization Writers about religion and science Writers about the Soviet Union

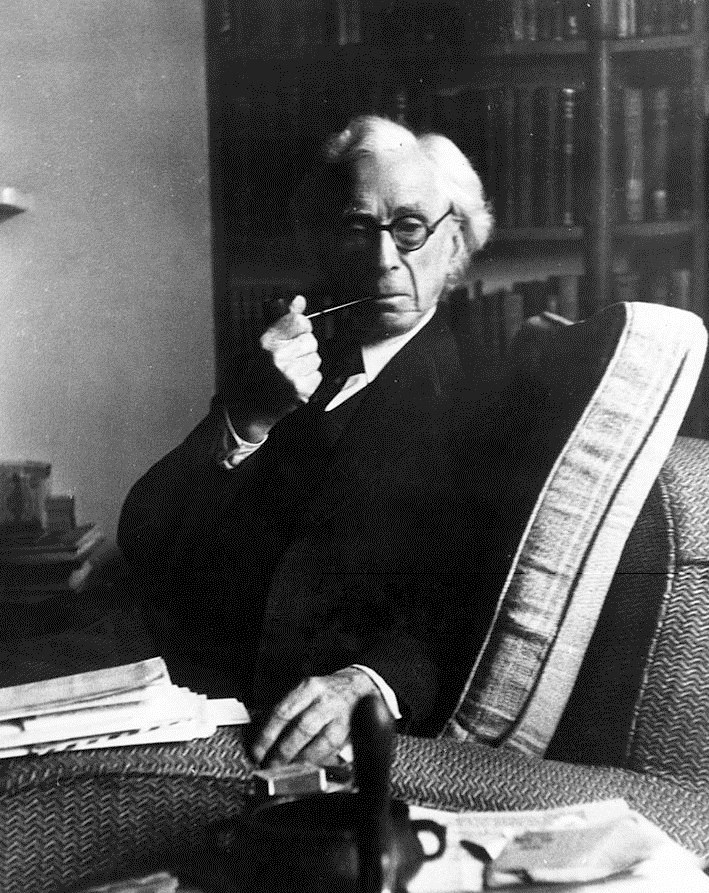

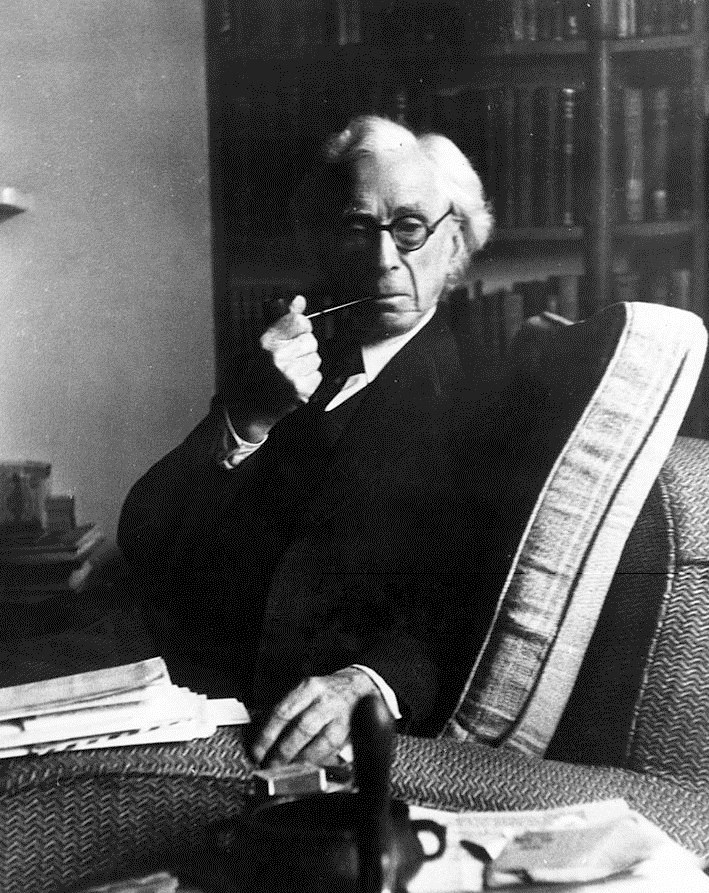

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and

"Bertrand Russell"

1 May 2003. He was one of the early 20th century's most prominent logicians, and a founder of analytic philosophy, along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege, his friend and colleague

His paternal grandfather, Lord John Russell, later 1st Earl Russell (1792–1878), had twice been

His paternal grandfather, Lord John Russell, later 1st Earl Russell (1792–1878), had twice been

Russell's adolescence was lonely and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests in "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from complete despondency;" only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors.The Nobel Foundation (1950)

Russell's adolescence was lonely and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests in "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from complete despondency;" only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors.The Nobel Foundation (1950)

Bertrand Russell: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950

Retrieved 11 June 2007. When Russell was eleven years old, his brother Frank introduced him to the work of Euclid, which he described in his autobiography as "one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love". During these formative years he also discovered the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Russell wrote: "I spent all my spare time reading him, and learning him by heart, knowing no one to whom I could speak of what I thought or felt, I used to reflect how wonderful it would have been to know Shelley, and to wonder whether I should meet any live human being with whom I should feel so much sympathy." Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of Christian religious dogma, which he found unconvincing. At this age, he came to the conclusion that there is no

Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and began his studies there in 1890, taking as coach

Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and began his studies there in 1890, taking as coach

The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism by Bertrand Russell

1920 about his experiences on this trip, taken with a group of 24 others from the UK, all of whom came home thinking well of the Soviet regime, despite Russell's attempts to change their minds. For example, he told them that he had heard shots fired in the middle of the night and was sure that these were clandestine executions, but the others maintained that it was only cars backfiring. Russell's lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Soviet Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution.

The following year, Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited

Russell's lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Soviet Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution.

The following year, Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited

''

Russell participated in many broadcasts over the

Russell participated in many broadcasts over the

, particularly ''public intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or ...

. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics

Linguistics is the science, scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure ...

, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to practical disciplines (includi ...

and various areas of analytic philosophy, especially philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

.Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy"Bertrand Russell"

1 May 2003. He was one of the early 20th century's most prominent logicians, and a founder of analytic philosophy, along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege, his friend and colleague

G. E. Moore

George Edward Moore (4 November 1873 – 24 October 1958) was an English philosopher, who with Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein and earlier Gottlob Frege was among the founders of analytic philosophy. He and Russell led the turn from ideal ...

and his student and protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

. Russell with Moore led the British "revolt against idealism". Together with his former teacher A. N. Whitehead, Russell wrote ''Principia Mathematica

The ''Principia Mathematica'' (often abbreviated ''PM'') is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. ...

'', a milestone in the development of classical logic, and a major attempt to reduce the whole of mathematics to logic (see Logicism

In the philosophy of mathematics, logicism is a programme comprising one or more of the theses that — for some coherent meaning of 'logic' — mathematics is an extension of logic, some or all of mathematics is reducible to logic, or some or all ...

). Russell's article " On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy".

Russell was a pacifist who championed anti-imperialism and chaired the India League. He occasionally advocated preventive nuclear war, before the opportunity provided by the atomic monopoly had passed and he decided he would "welcome with enthusiasm" world government. He went to prison for his pacifism during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Later, Russell concluded that the war against Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

was a necessary "lesser of two evils" and also criticized Stalinist totalitarianism, condemned the United States' war on Vietnam and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

. In 1950, Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought". He was also the recipient of the De Morgan Medal

The De Morgan Medal is a prize for outstanding contribution to mathematics, awarded by the London Mathematical Society. The Society's most prestigious award, it is given in memory of Augustus De Morgan, who was the first President of the society ...

(1932), Sylvester Medal

The Sylvester Medal is a bronze medal awarded by the Royal Society (London) for the encouragement of mathematical research, and accompanied by a £1,000 prize. It was named in honour of James Joseph Sylvester, the Savilian Professor of Geometry a ...

(1934), Kalinga Prize

The Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science is an award given by UNESCO for exceptional skill in presenting scientific ideas to lay people. It was created in 1952, following a donation from Biju Patnaik, Founder President of the Kalinga ...

(1957), and Jerusalem Prize (1963).

Biography

Early life and background

Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born at Ravenscroft,Trellech

Trellech (occasionally spelt Trelech, Treleck or Trelleck; cy, Tryleg) is a village and parish in Monmouthshire, south-east Wales. Located south of Monmouth and north-north-west of Tintern, Trellech lies on a plateau above the Wye Valley on t ...

, Monmouthshire, United Kingdom, on 18 May 1872, into an influential and liberal family of the British aristocracy

The British nobility is made up of the peerage and the (landed) gentry. The nobility of its four constituent home nations has played a major role in shaping the history of the country, although now they retain only the rights to stand for election ...

. His parents, Viscount and Viscountess Amberley, were radical for their times. Lord Amberley consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor, the biologist Douglas Spalding

Douglas Alexander Spalding (14 July 1841 – 1877) was a British biologist who studied animal behaviour and worked in the home of Viscount Amberley.

Biography

Spalding was born in Islington in London in 1841, the only son of Jessey Fraser and A ...

. Both were early advocates of birth control at a time when this was considered scandalous. Lord Amberley was a deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, and even asked the philosopher John Stuart Mill to act as Russell's secular godfather. Mill died the year after Russell's birth, but his writings had a great effect on Russell's life.

His paternal grandfather, Lord John Russell, later 1st Earl Russell (1792–1878), had twice been

His paternal grandfather, Lord John Russell, later 1st Earl Russell (1792–1878), had twice been prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

in the 1840s and 1860s. A member of Parliament since the early 1810s, he met with Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

in Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano Nationa ...

. The Russells had been prominent in England for several centuries before this, coming to power and the peerage with the rise of the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

(see: Duke of Bedford

Duke of Bedford (named after Bedford, England) is a title that has been created six times (for five distinct people) in the Peerage of England. The first and second creations came in 1414 and 1433 respectively, in favour of Henry IV's third so ...

). They established themselves as one of the leading Whig families and participated in every great political event from the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536–1540 to the Glorious Revolution in 1688–1689 and the Great Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

in 1832.G. E. Cokayne,; Vicary Gibbs, H. A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed. 13 volumes in 14. 1910–1959. Reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000.

Lady Amberley was the daughter of Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

and Lady Stanley of Alderley. Russell often feared the ridicule of his maternal grandmother, one of the campaigners for education of women

Female education is a catch-all term of a complex set of issues and debates surrounding education (primary education, secondary education, tertiary education, and health education in particular) for girls and women. It is frequently called girl ...

.

Childhood and adolescence

Russell had two siblings: brotherFrank

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curr ...

(nearly seven years older than Bertrand), and sister Rachel (four years older). In June 1874, Russell's mother died of diphtheria, followed shortly by Rachel's death. In January 1876, his father died of bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

after a long period of depression. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of staunchly Victorian paternal grandparents, who lived at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park

Richmond Park, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, is the largest of London's Royal Parks, and is of national and international importance for wildlife conservation. It was created by Charles I in the 17th century as a deer park ...

. His grandfather, former Prime Minister Earl Russell, died in 1878, and was remembered by Russell as a kindly old man in a wheelchair. His grandmother, the Countess Russell (née Lady Frances Elliot), was the dominant family figure for the rest of Russell's childhood and youth.

The Countess was from a Scottish Presbyterian family and successfully petitioned the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equ ...

to set aside a provision in Amberley's will requiring the children to be raised as agnostics. Despite her religious conservatism, she held progressive views in other areas (accepting Darwinism and supporting Irish Home Rule), and her influence on Bertrand Russell's outlook on social justice and standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life. Her favourite Bible verse, "Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil", became his motto. The atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of frequent prayer, emotional repression and formality; Frank reacted to this with open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings.

Russell's adolescence was lonely and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests in "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from complete despondency;" only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors.The Nobel Foundation (1950)

Russell's adolescence was lonely and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests in "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from complete despondency;" only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors.The Nobel Foundation (1950)Bertrand Russell: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950

Retrieved 11 June 2007. When Russell was eleven years old, his brother Frank introduced him to the work of Euclid, which he described in his autobiography as "one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love". During these formative years he also discovered the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Russell wrote: "I spent all my spare time reading him, and learning him by heart, knowing no one to whom I could speak of what I thought or felt, I used to reflect how wonderful it would have been to know Shelley, and to wonder whether I should meet any live human being with whom I should feel so much sympathy." Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of Christian religious dogma, which he found unconvincing. At this age, he came to the conclusion that there is no

free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

and, two years later, that there is no life after death. Finally, at the age of 18, after reading Mill's ''Autobiography'', he abandoned the " First Cause" argument and became an atheist.

He travelled to the continent in 1890 with an American friend, Edward FitzGerald, and with FitzGerald's family he visited the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and climbed the Eiffel Tower soon after it was completed.

University and first marriage

Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and began his studies there in 1890, taking as coach

Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and began his studies there in 1890, taking as coach Robert Rumsey Webb

Robert Rumsey Webb (9 July 1850 – 29 July 1936), known as R. R. Webb, was a successful coach for the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos. Webb coached 100 students to place in the top ten wranglers from 1865 to 1909, a record second only to Edwar ...

. He became acquainted with the younger George Edward Moore

George Edward Moore (4 November 1873 – 24 October 1958) was an English philosopher, who with Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein and earlier Gottlob Frege was among the founders of analytic philosophy. He and Russell led the turn from ideal ...

and came under the influence of Alfred North Whitehead, who recommended him to the Cambridge Apostles. He quickly distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy, graduating as seventh Wrangler in the former in 1893 and becoming a Fellow in the latter in 1895.

Russell was 17 years old in the summer of 1889 when he met the family of Alys Pearsall Smith

Alyssa Whitall "Alys" Pearsall Smith (21 July 1867 – 22 January 1951) was an American-born British Quaker relief organiser and the first wife of Bertrand Russell. She chaired the society that created an innovative school for mothers in 1907.

...

, an American Quaker five years older, who was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

. He became a friend of the Pearsall Smith family. They knew him primarily as "Lord John's grandson" and enjoyed showing him off.

He soon fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys, and contrary to his grandmother's wishes, married her on 13 December 1894. Their marriage began to fall apart in 1901 when it occurred to Russell, while cycling, that he no longer loved her. She asked him if he loved her and he replied that he did not. Russell also disliked Alys's mother, finding her controlling and cruel. A lengthy period of separation began in 1911 with Russell's affair with Lady Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befriended writers including Aldous Huxley, Siegfr ...

, and he and Alys finally divorced in 1921 to enable Russell to remarry.

During his years of separation from Alys, Russell had passionate (and often simultaneous) affairs with a number of women, including Morrell and the actress Lady Constance Malleson. Some have suggested that at this point he had an affair with Vivienne Haigh-Wood, the English governess and writer, and first wife of T. S. Eliot.

Early career

Russell began his published work in 1896 with ''German Social Democracy'', a study in politics that was an early indication of a lifelong interest in political and social theory. In 1896 he taught German social democracy at theLondon School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

. He was a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb.

He now started an intensive study of the foundations of mathematics

Foundations of mathematics is the study of the philosophical and logical and/or algorithmic basis of mathematics, or, in a broader sense, the mathematical investigation of what underlies the philosophical theories concerning the nature of mathe ...

at Trinity. In 1897, he wrote ''An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry'' (submitted at the Fellowship Examination of Trinity College) which discussed the Cayley–Klein metrics used for non-Euclidean geometry

In mathematics, non-Euclidean geometry consists of two geometries based on axioms closely related to those that specify Euclidean geometry. As Euclidean geometry lies at the intersection of metric geometry and affine geometry, non-Euclidean g ...

. He attended the First International Congress of Philosophy

The World Congress of Philosophy (originally known as the International Congress of Philosophy) is a global meeting of philosophers held every five years under the auspices of the International Federation of Philosophical Societies (FISP). First or ...

in Paris in 1900 where he met Giuseppe Peano

Giuseppe Peano (; ; 27 August 1858 – 20 April 1932) was an Italian mathematician and glottologist. The author of over 200 books and papers, he was a founder of mathematical logic and set theory, to which he contributed much notation. The sta ...

and Alessandro Padoa. The Italians had responded to Georg Cantor, making a science of set theory; they gave Russell their literature including the ''Formulario mathematico

''Formulario Mathematico'' (Latino sine flexione: ''Formulary for Mathematics'') is a book

There are many editions. Here are two:

* (French) Published 1901 by Gauthier-Villars, Paris. 230p.OpenLibrary OL15255022WRussell's paradox

In mathematical logic, Russell's paradox (also known as Russell's antinomy) is a set-theoretic paradox discovered by the British philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell in 1901. Russell's paradox shows that every set theory that contains ...

. In 1903 he published ''The Principles of Mathematics

''The Principles of Mathematics'' (''PoM'') is a 1903 book by Bertrand Russell, in which the author presented his famous Russell's paradox, paradox and argued his thesis that mathematics and logic are identical.

The book presents a view of ...

'', a work on foundations of mathematics. It advanced a thesis of logicism

In the philosophy of mathematics, logicism is a programme comprising one or more of the theses that — for some coherent meaning of 'logic' — mathematics is an extension of logic, some or all of mathematics is reducible to logic, or some or all ...

, that mathematics and logic are one and the same.

At the age of 29, in February 1901, Russell underwent what he called a "sort of mystic illumination", after witnessing Whitehead's wife's acute suffering in an angina attack. "I found myself filled with semi-mystical feelings about beauty... and with a desire almost as profound as that of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

to find some philosophy which should make human life endurable", Russell would later recall. "At the end of those five minutes, I had become a completely different person."

In 1905, he wrote the essay " On Denoting", which was published in the philosophical journal '' Mind''. Russell was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1908. The three-volume ''Principia Mathematica

The ''Principia Mathematica'' (often abbreviated ''PM'') is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. ...

'', written with Whitehead, was published between 1910 and 1913. This, along with the earlier ''The Principles of Mathematics'', soon made Russell world-famous in his field.

In 1910, he became a University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

lecturer at Trinity College, where he had studied. He was considered for a Fellowship, which would give him a vote in the college government and protect him from being fired for his opinions, but was passed over because he was "anti-clerical", essentially because he was agnostic. He was approached by the Austrian engineering student Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

, who became his PhD student. Russell viewed Wittgenstein as a genius and a successor who would continue his work on logic. He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein's various phobias and his frequent bouts of despair. This was often a drain on Russell's energy, but Russell continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his academic development, including the publication of Wittgenstein's '' Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus'' in 1922. Russell delivered his lectures on logical atomism

Logical atomism is a philosophical view that originated in the early 20th century with the development of analytic philosophy. Its principal exponent was the British philosopher Bertrand Russell. It is also widely held that the early works of his ...

, his version of these ideas, in 1918, before the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Wittgenstein was, at that time, serving in the Austrian Army and subsequently spent nine months in an Italian prisoner of war camp at the end of the conflict.

First World War

DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Russell was one of the few people to engage in active pacifist activities. In 1916, because of his lack of a Fellowship, he was dismissed from Trinity College following his conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed in the United Kingdom on 8 August 1914, four days after it entered the First World War and was added to as the war progressed. It gave the government wide-ranging powers during the war, such as the p ...

. He later described this, in '' Free Thought and Official Propaganda'', as an illegitimate means the state used to violate freedom of expression. Russell championed the case of Eric Chappelow, a poet jailed and abused as a conscientious objector. Caroline Moorehead, ''Bertrand Russell: A Life'' (1992), p. 247. Russell played a significant part in the ''Leeds Convention'' in June 1917, a historic event which saw well over a thousand "anti-war socialists" gather; many being delegates from the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

and the Socialist Party, united in their pacifist beliefs and advocating a peace settlement. The international press reported that Russell appeared with a number of Labour Members of Parliament (MPs), including Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden

Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden, PC (; 18 July 1864 – 15 May 1937) was a British politician. A strong speaker, he became popular in trade union circles for his denunciation of capitalism as unethical and his promise of a socialist utop ...

, as well as former Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

MP and anti-conscription campaigner, Professor Arnold Lupton

Arnold Lupton (11 September 1846 – 23 May 1930) was a British Liberal Party Member of Parliament, academic, anti-vaccinationist, mining engineer and a managing director (collieries). He was jailed for pacifist activity during the First ...

. After the event, Russell told Lady Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befriended writers including Aldous Huxley, Siegfr ...

that, "to my surprise, when I got up to speak, I was given the greatest ovation that was possible to give anybody".

His conviction in 1916 resulted in Russell being fined £100 (), which he refused to pay in hope that he would be sent to prison, but his books were sold at auction to raise the money. The books were bought by friends; he later treasured his copy of the King James Bible that was stamped "Confiscated by Cambridge Police".

A later conviction for publicly lecturing against inviting the United States to enter the war on the United Kingdom's side resulted in six months' imprisonment in Brixton Prison

HM Prison Brixton is a local men's prison, located in Brixton area of the London Borough of Lambeth, in inner-South London. The prison is operated by His Majesty's Prison Service.

History

The prison was originally built in 1820 and opened a ...

(see '' Bertrand Russell's political views'') in 1918. He later said of his imprisonment:

While he was reading Strachey Strachey is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Strachey family of Sutton Court, Somerset

*John Strachey (d. 1674), friend of John Locke

**John Strachey (geologist) (1671–1743), British geologist

***Henry Strachey of Sutton Cour ...

's ''Eminent Victorians

''Eminent Victorians'' is a book by Lytton Strachey (one of the older members of the Bloomsbury Group), first published in 1918, and consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era. Its fame rests on the irreverence and w ...

'' chapter about Gordon

Gordon may refer to:

People

* Gordon (given name), a masculine given name, including list of persons and fictional characters

* Gordon (surname), the surname

* Gordon (slave), escaped to a Union Army camp during the U.S. Civil War

* Clan Gordon, ...

he laughed out loud in his cell prompting the warder to intervene and reminding him that "prison was a place of punishment".

Russell was reinstated to Trinity in 1919, resigned in 1920, was Tarner Lecturer in 1926 and became a Fellow again in 1944 until 1949.

In 1924, Russell again gained press attention when attending a "banquet" in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

with well-known campaigners, including Arnold Lupton

Arnold Lupton (11 September 1846 – 23 May 1930) was a British Liberal Party Member of Parliament, academic, anti-vaccinationist, mining engineer and a managing director (collieries). He was jailed for pacifist activity during the First ...

, who had been an MP and had also endured imprisonment for "passive resistance to military or naval service".

G. H. Hardy on the Trinity controversy

In 1941, G. H. Hardy wrote a 61-page pamphlet titled ''Bertrand Russell and Trinity'' – published later as a book by Cambridge University Press with a foreword byC. D. Broad

Charlie Dunbar Broad (30 December 1887 – 11 March 1971), usually cited as C. D. Broad, was an English people, English epistemology, epistemologist, history of philosophy, historian of philosophy, philosophy of science, philosopher of sc ...

—in which he gave an authoritative account of Russell's 1916 dismissal from Trinity College, explaining that a reconciliation between the college and Russell had later taken place and gave details about Russell's personal life. Hardy writes that Russell's dismissal had created a scandal since the vast majority of the Fellows of the College opposed the decision. The ensuing pressure from the Fellows induced the Council to reinstate Russell. In January 1920, it was announced that Russell had accepted the reinstatement offer from Trinity and would begin lecturing from October. In July 1920, Russell applied for a one year leave of absence; this was approved. He spent the year giving lectures in China and Japan. In January 1921, it was announced by Trinity that Russell had resigned and his resignation had been accepted. This resignation, Hardy explains, was completely voluntary and was not the result of another altercation.

The reason for the resignation, according to Hardy, was that Russell was going through a tumultuous time in his personal life with a divorce and subsequent remarriage. Russell contemplated asking Trinity for another one-year leave of absence but decided against it, since this would have been an "unusual application" and the situation had the potential to snowball into another controversy. Although Russell did the right thing, in Hardy's opinion, the reputation of the College suffered with Russell's resignation, since the 'world of learning' knew about Russell's altercation with Trinity but not that the rift had healed. In 1925, Russell was asked by the Council of Trinity College to give the ''Tarner Lectures'' on the Philosophy of the Sciences; these would later be the basis for one of Russell's best-received books according to Hardy: ''The Analysis of Matter'', published in 1927. In the preface to the Trinity pamphlet, Hardy wrote:

Between the wars

In August 1920, Russell travelled toSoviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

as part of an official delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the Russian Revolution. He wrote a four-part series of articles, titled "Soviet Russia—1920", for the magazine '' The Nation''. He met Vladimir Lenin and had an hour-long conversation with him. In his autobiography, he mentions that he found Lenin disappointing, sensing an "impish cruelty" in him and comparing him to "an opinionated professor". He cruised down the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

on a steamship. His experiences destroyed his previous tentative support for the revolution. He subsequently wrote a book, ''The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism'',Russell, BertranThe Practice and Theory of Bolshevism by Bertrand Russell

1920 about his experiences on this trip, taken with a group of 24 others from the UK, all of whom came home thinking well of the Soviet regime, despite Russell's attempts to change their minds. For example, he told them that he had heard shots fired in the middle of the night and was sure that these were clandestine executions, but the others maintained that it was only cars backfiring.

Russell's lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Soviet Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution.

The following year, Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited

Russell's lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Soviet Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution.

The following year, Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

(as Beijing was then known outside of China) to lecture on philosophy for a year. He went with optimism and hope, seeing China as then being on a new path. Other scholars present in China at the time included John Dewey and Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian Nobel-laureate poet. Before leaving China, Russell became gravely ill with pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

, and incorrect reports of his death were published in the Japanese press. When the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora took on the role of spurning the local press by handing out notices reading "Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists". Apparently they found this harsh and reacted resentfully.

Dora was six months pregnant when the couple returned to England on 26 August 1921. Russell arranged a hasty divorce from Alys, marrying Dora six days after the divorce was finalised, on 27 September 1921. Russell's children with Dora were John Conrad Russell, 4th Earl Russell, born on 16 November 1921, and Katharine Jane Russell (now Lady Katharine Tait), born on 29 December 1923. Russell supported his family during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, ethics, and education to the layman.

From 1922 to 1927 the Russells divided their time between London and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, spending summers in Porthcurno. In the 1922 and 1923 general elections Russell stood as a Labour Party candidate in the Chelsea constituency, but only on the basis that he knew he was extremely unlikely to be elected in such a safe Conservative seat, and he was unsuccessful on both occasions.

After the birth of his two children, he became interested in education, especially early childhood education

Early childhood education (ECE), also known as nursery education, is a branch of education theory that relates to the teaching of children (formally and informally) from birth up to the age of eight. Traditionally, this is up to the equival ...

. He was not satisfied with the old traditional education

Traditional education, also known as back-to-basics, conventional education or customary education, refers to long-established customs that society has traditionally used in schools. Some forms of education reform promote the adoption of progressiv ...

and thought that progressive education also had some flaws; as a result, together with Dora, Russell founded the experimental Beacon Hill School in 1927. The school was run from a succession of different locations, including its original premises at the Russells' residence, Telegraph House, near Harting

Harting is a civil parish in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England. It is situated on the northern flank of the South Downs, around southeast of Petersfield in Hampshire. It comprises the village of South Harting and the hamlets of ...

, West Sussex. During this time, he published " On Education, Especially in Early Childhood". On 8 July 1930 Dora gave birth to her third child Harriet Ruth. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943.Inside Beacon Hill: Bertrand Russell as Schoolmaster. Jespersen, Shirley ERIC# EJ360344, published 1987

In 1927 Russell met Barry Fox (later Barry Stevens), who became a well-known Gestalt therapist and writer in later years. They developed an intensive relationship, and in Fox's words: "...for three years we were very close." Fox sent her daughter Judith to Beacon Hill School. From 1927 to 1932 Russell wrote 34 letters to Fox.

Upon the death of his elder brother Frank, in 1931, Russell became the 3rd Earl Russell.

Russell's marriage to Dora grew increasingly tenuous, and it reached a breaking point over her having two children with an American journalist, Griffin Barry. They separated in 1932 and finally divorced. On 18 January 1936, Russell married his third wife, an Oxford undergraduate named Patricia ("Peter") Spence, who had been his children's governess since 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell, 5th Earl Russell, who became a prominent historian and one of the leading figures in the Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties usually follow a liberal democratic ideology.

Active parties

Former parties

See also

*Liberal democracy

*Lib ...

party.

Russell returned in 1937 to the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

to lecture on the science of power.

During the 1930s, Russell became friend and collaborator of V. K. Krishna Menon, then President of the India League, the foremost lobby in the United Kingdom for Indian self-rule. Russell was chair of the India League from 1932–1939.

Second World War

Russell's political views changed over time, mostly about war. He opposed rearmament againstNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In 1937, he wrote in a personal letter: "If the Germans succeed in sending an invading army to England we should do best to treat them as visitors, give them quarters and invite the commander and chief to dine with the prime minister." In 1940, he changed his appeasement view that avoiding a full-scale world war was more important than defeating Hitler. He concluded that Adolf Hitler taking over all of Europe would be a permanent threat to democracy. In 1943, he adopted a stance toward large-scale warfare called "relative political pacifism": "War was always a great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances, it may be the lesser of two evils."

Before World War II, Russell taught at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, later moving on to Los Angeles to lecture at the UCLA Department of Philosophy.Bertrand Russell Rides Out Collegiate Cyclone''

Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

'', Vol. 8, No. 14, 1 April 1940 He was appointed professor at the City College of New York (CCNY) in 1940, but after a public outcry the appointment was annulled by a court judgment that pronounced him "morally unfit" to teach at the college because of his opinions, especially those relating to sexual morality

Sexual ethics (also known as sex ethics or sexual morality) is a branch of philosophy that considers the ethics or morality or otherwise in sexual behavior. Sexual ethics seeks to understand, evaluate and critique interpersonal relationships and ...

, detailed in '' Marriage and Morals'' (1929). The matter was however taken to the New York Supreme Court by Jean Kay who was afraid that her daughter would be harmed by the appointment, though her daughter was not a student at CCNY. Many intellectuals, led by John Dewey, protested at his treatment. Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

's oft-quoted aphorism that "great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds" originated in his open letter, dated 19 March 1940, to Morris Raphael Cohen, a professor emeritus at CCNY, supporting Russell's appointment. Dewey and Horace M. Kallen edited a collection of articles on the CCNY affair in ''The Bertrand Russell Case

''The Bertrand Russell Case'', known officially as ''Kay v. Board of Higher Education'', was a case concerning the appointment of Bertrand Russell as Professor of Philosophy of the College of the City of New York, as well as a collection of arti ...

''. Russell soon joined the Barnes Foundation

The Barnes Foundation is an art collection and educational institution promoting the appreciation of art and horticulture. Originally in Merion, the art collection moved in 2012 to a new building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, Penn ...

, lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy; these lectures formed the basis of ''A History of Western Philosophy

''A History of Western Philosophy'' is a 1946 book by the philosopher Bertrand Russell. A survey of Western philosophy from the pre-Socratic philosophers to the early 20th century, it was criticised for Russell's over-generalization and omissio ...

''. His relationship with the eccentric Albert C. Barnes soon soured, and he returned to the UK in 1944 to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College.

Later life

Russell participated in many broadcasts over the

Russell participated in many broadcasts over the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

'' and for the Third Programme

The BBC Third Programme was a national radio station produced and broadcast from 1946 until 1967, when it was replaced by Radio 3. It first went on the air on 29 September 1946 and quickly became one of the leading cultural and intellectual f ...

, on various topical and philosophical subjects. By this time Russell was world-famous outside academic circles, frequently the subject or author of magazine and newspaper articles, and was called upon to offer opinions on a wide variety of subjects, even mundane ones. En route to one of his lectures in Trondheim, Russell was one of 24 survivors (among a total of 43 passengers) of an aeroplane crash in Hommelvik in October 1948. He said he owed his life to smoking since the people who drowned were in the non-smoking part of the plane. ''A History of Western Philosophy

''A History of Western Philosophy'' is a 1946 book by the philosopher Bertrand Russell. A survey of Western philosophy from the pre-Socratic philosophers to the early 20th century, it was criticised for Russell's over-generalization and omissio ...

'' (1945) became a best-seller and provided Russell with a steady income for the remainder of his life.

In 1942, Russell argued in favour of a moderate socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

, capable of overcoming its metaphysical principles. In an inquiry on dialectical materialism, launched by the Austrian artist and philosopher Wolfgang Paalen

Wolfgang Robert Paalen (July 22, 1905 in Vienna, Austria – September 24, 1959 in Taxco, Mexico) was an Austrian-Mexican painter, sculptor, and art philosopher. A member of the Abstraction-Création group from 1934 to 1935, he joined the influ ...

in his journal '' DYN'', Russell said: "I think the metaphysics of both Hegel and Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

plain nonsense—Marx's claim to be 'science' is no more justified than Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879. She also founded ''The Christian Science Monitor'', a Pulitzer Prize-winning se ...

's. This does not mean that I am opposed to socialism."

In 1943, Russell expressed support for Zionism: "I have come gradually to see that, in a dangerous and largely hostile world, it is essential to Jews to have some country which is theirs, some region where they are not suspected aliens, some state which embodies what is distinctive in their culture".

In a speech in 1948, Russell said that if the USSR's aggression continued, it would be morally worse to go to war after the USSR possessed an atomic bomb than before it possessed one, because if the USSR had no bomb the West's victory would come more swiftly and with fewer casualties than if there were atomic bombs on both sides. At that time, only the United States possessed an atomic bomb, and the USSR was pursuing an extremely aggressive policy towards the countries in Eastern Europe which were being absorbed into the Soviet Union's sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

. Many understood Russell's comments to mean that Russell approved of a first strike in a war with the USSR, including Nigel Lawson, who was present when Russell spoke of such matters. Others, including Griffin, who obtained a transcript of the speech, have argued that he was merely explaining the usefulness of America's atomic arsenal in deterring the USSR from continuing its domination of Eastern Europe.

Just after the atomic bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Russell wrote letters, and published articles in newspapers from 1945 to 1948, stating clearly that it was morally justified and better to go to war against the USSR using atomic bombs while the United States possessed them and before the USSR did. In September 1949, one week after the USSR tested its first A-bomb, but before this became known, Russell wrote that USSR would be unable to develop nuclear weapons because following Stalin's purges only science based on Marxist principles would be practised in the Soviet Union. After it became known that the USSR had carried out its nuclear bomb tests, Russell declared his position advocating the total abolition of atomic weapons.

In 1948, Russell was invited by the BBC to deliver the inaugural Reith Lectures—what was to become an annual series of lectures, still broadcast by the BBC. His series of six broadcasts, titled ''Authority and the Individual'', explored themes such as the role of individual initiative in the development of a community and the role of state control in a progressive society. Russell continued to write about philosophy. He wrote a foreword to ''Words and Things'' by Ernest Gellner

Ernest André Gellner FRAI (9 December 1925 – 5 November 1995) was a British- Czech philosopher and social anthropologist described by ''The Daily Telegraph'', when he died, as one of the world's most vigorous intellectuals, and by ''The ...

, which was highly critical of the later thought of Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

and of ordinary language philosophy

Ordinary language philosophy (OLP) is a philosophical methodology that sees traditional philosophical problems as rooted in misunderstandings philosophers develop by distorting or forgetting how words are ordinarily used to convey meaning in ...

. Gilbert Ryle

Gilbert Ryle (19 August 1900 – 6 October 1976) was a British philosopher, principally known for his critique of Cartesian dualism, for which he coined the phrase "ghost in the machine." He was a representative of the generation of British ord ...

refused to have the book reviewed in the philosophical journal '' Mind'', which caused Russell to respond via ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

''. The result was a month-long correspondence in ''The Times'' between the supporters and detractors of ordinary language philosophy, which was only ended when the paper published an editorial critical of both sides but agreeing with the opponents of ordinary language philosophy.

In the King's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the reigning British monarch's official birthday by granting various individuals appointment into national or dynastic orders or the award of decorations and medals. The honours are prese ...

of 9 June 1949, Russell was awarded the Order of Merit, and the following year he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. When he was given the Order of Merit, George VI was affable but slightly embarrassed at decorating a former jailbird, saying, "You have sometimes behaved in a manner that would not do if generally adopted". Russell merely smiled, but afterwards claimed that the reply "That's right, just like your brother" immediately came to mind.

In 1950, Russell attended the inaugural conference for the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA-funded anti-communist organisation committed to the deployment of culture as a weapon during the Cold War. Russell was one of the best-known patrons of the Congress, until he resigned in 1956.

In 1952, Russell was divorced by Spence, with whom he had been very unhappy. Conrad, Russell's son by Spence, did not see his father between the time of the divorce and 1968 (at which time his decision to meet his father caused a permanent breach with his mother). Russell married his fourth wife, Edith Finch, soon after the divorce, on 15 December 1952. They had known each other since 1925, and Edith had taught English at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, sharing a house for 20 years with Russell's old friend Lucy Donnelly. Edith remained with him until his death, and, by all accounts, their marriage was a happy, close, and loving one. Russell's eldest son John suffered from serious mental illness, which was the source of ongoing disputes between Russell and his former wife Dora.

In September 1961, at the age of 89, Russell was jailed for seven days in Brixton Prison

HM Prison Brixton is a local men's prison, located in Brixton area of the London Borough of Lambeth, in inner-South London. The prison is operated by His Majesty's Prison Service.

History

The prison was originally built in 1820 and opened a ...

for a "breach of the peace" after taking part in an anti-nuclear demonstration in London. The magistrate offered to exempt him from jail if he pledged himself to "good behaviour", to which Russell replied: "No, I won't."

In 1962 Russell played a public role in the Cuban Missile Crisis: in an exchange of telegrams with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev assured him that the Soviet government would not be reckless. Russell sent this telegram to President Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until assassination of Joh ...

:

YOUR ACTION DESPERATE. THREAT TO HUMAN SURVIVAL. NO CONCEIVABLE JUSTIFICATION. CIVILIZED MAN CONDEMNS IT. WE WILL NOT HAVE MASS MURDER. ULTIMATUM MEANS WAR... END THIS MADNESS.According to historian Peter Knight, after JFK's assassination, Russell, "prompted by the emerging work of the lawyer Mark Lane in the US ... rallied support from other noteworthy and left-leaning compatriots to form a Who Killed Kennedy Committee in June 1964, members of which included

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

MP, Caroline Benn, the publisher Victor Gollancz, the writers John Arden and J. B. Priestley

John Boynton Priestley (; 13 September 1894 – 14 August 1984) was an English novelist, playwright, screenwriter, broadcaster and social commentator.

His Yorkshire background is reflected in much of his fiction, notably in ''The Good Compa ...

, and the Oxford history professor Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper was a polemicist and essayist on a range of ...

." Russell published a highly critical article weeks before the Warren Commission Report was published, setting forth ''16 Questions on the Assassination'' and equating the Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

*Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbur ...

case with the Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

of late 19th-century France, in which the state convicted an innocent man. Russell also criticised the American press for failing to heed any voices critical of the official version.

Political causes

Bertrand Russell was opposed to war from a young age; his opposition to World War I being used as grounds for his dismissal from Trinity College at Cambridge. This incident fused two of his most controversial causes, as he had failed to be granted Fellow status which would have protected him from firing, because he was not willing to either pretend to be a devout Christian, or at least avoid admitting he was agnostic.

He later described the resolution of these issues as essential to freedom of thought and expression, citing the incident in Free Thought and Official Propaganda, where he explained that the expression of any idea, even the most obviously "bad", must be protected not only from direct State intervention, but also economic leveraging and other means of being silenced:

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in political causes primarily related to

Bertrand Russell was opposed to war from a young age; his opposition to World War I being used as grounds for his dismissal from Trinity College at Cambridge. This incident fused two of his most controversial causes, as he had failed to be granted Fellow status which would have protected him from firing, because he was not willing to either pretend to be a devout Christian, or at least avoid admitting he was agnostic.

He later described the resolution of these issues as essential to freedom of thought and expression, citing the incident in Free Thought and Official Propaganda, where he explained that the expression of any idea, even the most obviously "bad", must be protected not only from direct State intervention, but also economic leveraging and other means of being silenced:

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in political causes primarily related to nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

and opposing the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

. The 1955 Russell–Einstein Manifesto

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on 9 July 1955 by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international ...

was a document calling for nuclear disarmament and was signed by eleven of the most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the time. In 1966–1967, Russell worked with Jean-Paul Sartre and many other intellectual figures to form the Russell Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal to investigate the conduct of the United States in Vietnam. He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period.

Early in his life Russell supported eugenicist policies. He proposed in 1894 that the state issue certificates of health to prospective parents and withhold public benefits from those considered unfit. In 1929 he wrote that people deemed "mentally defective" and "feebleminded" should be sexually sterilized because they "are apt to have enormous numbers of illegitimate children, all, as a rule, wholly useless to the community." Russell was also an advocate of population control:The nations which at present increase rapidly should be encouraged to adopt the methods by which, in the West, the increase of population has been checked. Educational propaganda, with government help, could achieve this result in a generation. There are, however, two powerful forces opposed to such a policy: one is religion, the other is nationalism. I think it is the duty of all to proclaim that opposition to the spread of birth is appalling depth of misery and degradation, and that within another fifty years or so. I do not pretend that birth control is the only way in which population can be kept from increasing. There are others, which, one must suppose, opponents of birth control would prefer. War, as I remarked a moment ago, has hitherto been disappointing in this respect, but perhaps bacteriological war may prove more effective. If a Black Death could be spread throughout the whole world once in every generation survivors could procreate freely without making the world too full.On 20 November 1948, in a public speech at Westminster School, addressing a gathering arranged by the New Commonwealth, Russell shocked some observers by suggesting that a preemptive nuclear strike on the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

was justified. Russell argued that war between the United States and the Soviet Union seemed inevitable, so it would be a humanitarian gesture to get it over with quickly and have the United States in the dominant position. Currently, Russell argued, humanity could survive such a war, whereas a full nuclear war after both sides had manufactured large stockpiles of more destructive weapons was likely to result in the extinction of the human race. Russell later relented from this stance, instead arguing for mutual disarmament by the nuclear powers.

In 1956, immediately before and during the Suez Crisis, Russell expressed his opposition to European imperialism in the Middle East. He viewed the crisis as another reminder of the pressing need for a more effective mechanism for international governance, and to restrict national sovereignty to places such as the Suez Canal area "where general interest is involved". At the same time the Suez Crisis was taking place, the world was also captivated by the Hungarian Revolution and the subsequent crushing of the revolt by intervening Soviet forces. Russell attracted criticism for speaking out fervently against the Suez war while ignoring Soviet repression in Hungary, to which he responded that he did not criticise the Soviets "because there was no need. Most of the so-called Western World was fulminating". Although he later feigned a lack of concern, at the time he was disgusted by the brutal Soviet response, and on 16 November 1956, he expressed approval for a declaration of support for Hungarian scholars which Michael Polanyi

Michael Polanyi (; hu, Polányi Mihály; 11 March 1891 – 22 February 1976) was a Hungarian-British polymath, who made important theoretical contributions to physical chemistry, economics, and philosophy. He argued that positivism supplies ...

had cabled to the Soviet embassy in London twelve days previously, shortly after Soviet troops had entered Budapest.

In November 1957 Russell wrote an article addressing US President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, urging a summit to consider "the conditions of co-existence". Khrushchev responded that peace could be served by such a meeting. In January 1958 Russell elaborated his views in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...