Beriah Green on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

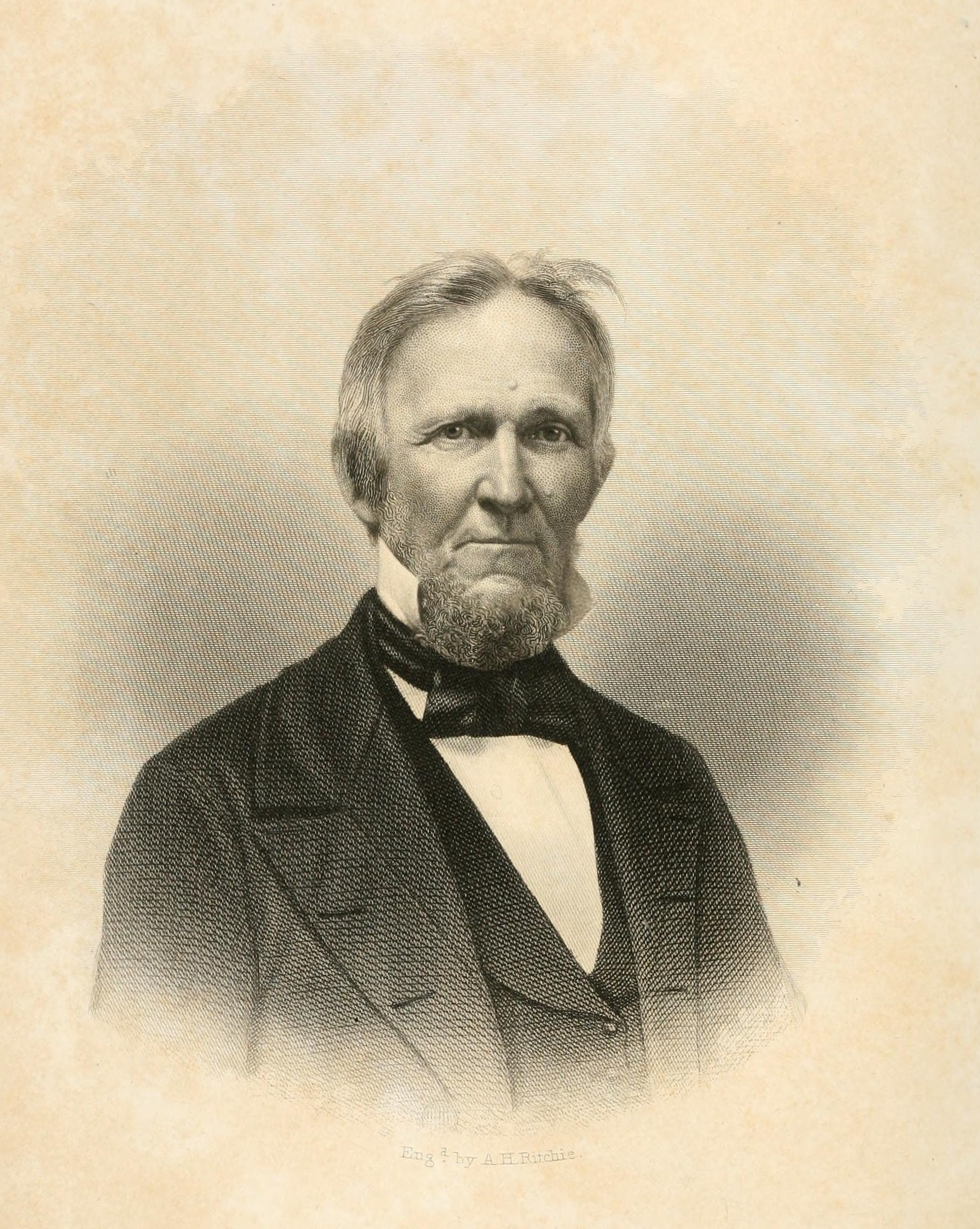

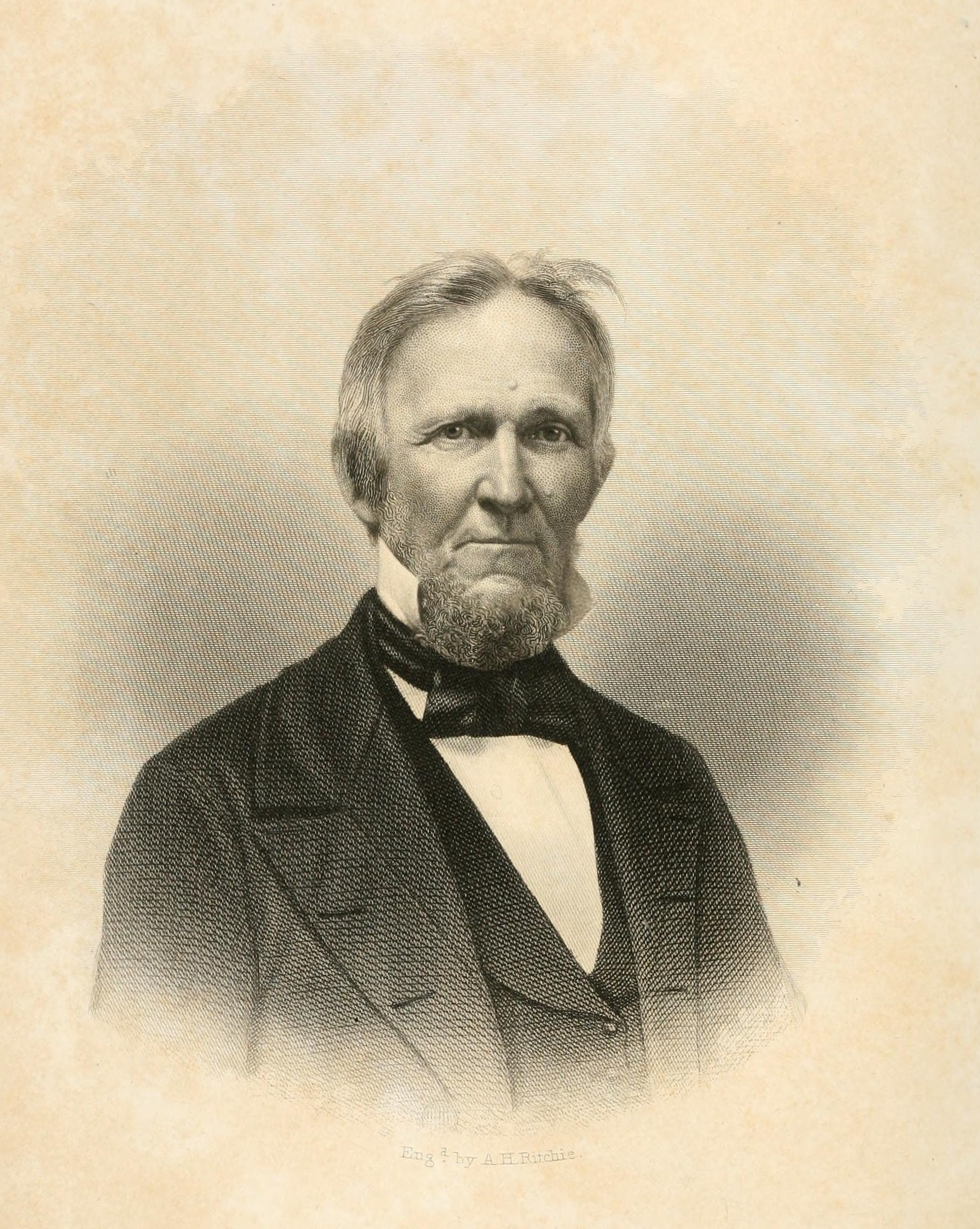

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer,

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer,

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer,

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer, abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

advocate, college professor, minister, and head of the Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at which black men were just as welcome ...

. He was "consumed totally by his abolitionist views". He has been described as "cantankerous". Former student Alexander Crummell

Alexander Crummell (March 3, 1819 – September 10, 1898) was a pioneering African-American minister, academic and African nationalist. Ordained as an Episcopal priest in the United States, Crummell went to England in the late 1840s to raise money ...

described him as a "bluff, kind-hearted man," a "master-thinker".

Early life

Greene was born inPreston, Connecticut

Preston is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 4,788 at the 2020 census. The town includes the villages of Long Society, Preston City, and Poquetanuck.

History

In 1686, Thomas Parke, Thomas Tracy, and seve ...

, son of Beriah Green (1774–1865) and Elizabeth Smith (1771–1840). His father was a cabinet and chair maker.

The family moved to Pawlet, Vermont

Pawlet is a town in Rutland County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,424 at the 2020 census.

History

Pawlet was one of the New Hampshire Grants, chartered from Benning Wentworth, Governor of colonial New Hampshire. The charter was gr ...

, in 1810, and he may have attended the Pawlet Academy. In 1815 he enrolled in the Kimball Union Academy, in New Hampshire. He graduated from Middlebury College in 1819, where he was valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

, and then studied to become a missionary (minister) at Andover Theological Seminary

Andover Theological Seminary (1807–1965) was a Congregationalist seminary founded in 1807 and originally located in Andover, Massachusetts on the campus of Phillips Academy. From 1908 to 1931, it was located at Harvard University in Cambridge. ...

(1819–20). However, his religious beliefs did not agree with any denominational creed.

Career

Because of financial need, he began teaching at Phillips Academy, also inAndover, Massachusetts

Andover is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. It was settled in 1642 and incorporated in 1646."Andover" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ed., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 387. As of th ...

. Suffering from health and vision problems, he left the seminary. After recovering, in January 1821 he married Marcia Deming of Middlebury, Vermont

Middlebury is the shire town (county seat) of Addison County, Vermont, United States. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the population was 9,152. Middlebury is home to Middlebury College and the Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History.

History

On ...

, and was briefly in the service of the Missionary Board in Lyme, Connecticut

Lyme is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States, situated on the eastern side of the Connecticut River. The population was 2,352 at the 2020 census. Lyme is the eponym of Lyme disease.

History

In February 1665, the portion of th ...

, and on Long Island. Having been ordained, in 1823 he became pastor of the Congregational Church in Brandon, Vermont

Brandon is a town in Rutland County, Vermont, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,129.

History

On October 20, 1761, the town of Neshobe was chartered to Capt. Josiah Powers. In October 1784, the name of the town was chang ...

. In 1826 his wife died, leaving him with two children, and the same year he married Daraxa Foote, also of Middlebury, who outlived Beriah. In 1829 he accepted a call to the distinctly "orthodox" (conservative) church of Kennebunk, Maine

Kennebunk is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 11,536 at the 2020 census (The population does not include Kennebunkport, a separate town). Kennebunk is home to several beaches, the Rachel Carson National Wildlife R ...

, but the next year left, to become a professor of sacred literature (Bible) in the one-man theological department of Western Reserve College and Preparatory School, in Hudson, Ohio

Hudson is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,110 at the 2020 census. It is a suburban community in the Akron metropolitan statistical area and the larger Cleveland–Akron–Canton Combined Statistical Area, t ...

, from Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

.

The buildings of this "Yale of the West" — Green calls it that

— imitated those of Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

. It had the same motto, "Lux et Veritas" (Light and Truth), the same entrance standards, and almost the same curriculum. It aspired to be as intellectually outstanding as Yale as well. For the time, it was well funded. It was a prestigious appointment.

The topic of slavery

In the Cleveland area (the "Connecticut Western Reserve

The Connecticut Western Reserve was a portion of land claimed by the Colony of Connecticut and later by the state of Connecticut in what is now mostly the northeastern region of Ohio. The Reserve had been granted to the Colony under the terms o ...

") Beriah came in contact with more African Americans than he had in Vermont or Maine. The college first admitted an African American student in 1832, John Sykes Fayette; he graduated in 1836. Three other African-American students — Richard W. Miller, Samuel Nelson, and Samuel Harrison — were also admitted during this time period. Fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

traveling to Canada on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

passed through northeast Ohio: John Brown, of the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, grew up in Hudson (1805–1825), running a tannery, then moved to a more isolated and safer (for fugitive slaves) site in northwest Pennsylvania, a major Underground Railroad stop. That the two met is possible but undocumented; there is no known correspondence between them. What is documented is his contact with Wm. Lloyd Garrison, who through his weekly newspaper '' The Liberator'', launched in 1831, led the fight for immediate, uncompensated liberation of all slaves. Green wrote that "One copy of Mr. Garrison's 'Thoughts' has reached us 'Thoughts on African Colonization'', 1832and we take a few copies of his admirable paper." Garrison was a great influence on Green; one way was to encourage Green to publish his sermons and other writings, which gave him influence.

Sending free blacks to Africa (" colonization") was the mission of the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

(ACS), founded by Quakers, and supported by state colonization societies and Southern slave owners. Free blacks were against it; they did not want to move to Africa, having lived for generations in the United States. They said they were no more African than the white Americans were British.

The debate started by Garrison's newspapers and book led to a heated campus debate. "Trustees, faculty, and students began to choose sides." College president Charles Backus Storrs had been a supporter of colonization as a solution to "the negro problem". But he read William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

's new abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'' and said that Garrison's views could not be refuted. His inaugural address, in February, 1831, invoked the abolitionism of William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

.

The influential Theodore Weld made a visit to Western Reserve in the fall of 1832. "Less than two months aftef Weld departed, Green was preaching abolitionism from the college pulpit." Green used the college chapel four Sundays in a row to attack the American Colonization Society and its supporters. This angered many trustees and clergymen.

The four sermons on slavery

Green's four sermons on slavery, delivered in November and December, 1832, constitute a turning point of national significance. One of the duties, or honors, of his job was delivering the weekly sermon from the pulpit of the college chapel: As fellow professor Elizur Wright wrote, Green was "pastor of our college church". In his sermons, Green took the position, unusual in his day, that negroes were the equals of whites, and the victims of irrational prejudice based on no more than the color of their skin. These sermons created "a rumpus" on the campus. Some people walked out of the first sermon, and they and more refused to hear the following sermons. Green, who frequently published pamphlets, had the four sermons published. In the pamphlet was a brief message from College President Storrs and Elizur Wright, another professor, certifying that the published texts were the same as those delivered in the College chapel, and that "the sentiments embodied on these discourses, we believe to be scriptural. The exhibition of them in the college-chapel...we believe to have been not only warranted, but imperiously demanded, by a just regard to pastoral fidelity." They were influential nationally, contributing to the foundation, the following year, of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Green presided over its founding meeting, and was chosen as its first President.The Oneida Institute

Expecting to be fired, Green resigned in 1833 and became the President of theOneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at which black men were just as welcome ...

, a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

institution in Whitesboro, New York. Green accepted the presidency at Oneida on two conditions: that he be allowed to preach immediatism (the immediate abolition of slavery), and that he be allowed to accept African-American students.

As President, Green dramatically changed the college by accepting numerous African Americans, more than any other college during the 1830s and 1840s. Green did not believe that it was right to have separate schools for blacks and whites. This belief led him to attempt to get Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

to merge his unsuccessful black manual labor school in Peterboro with the Oneida Institute, and it made Oneida a hotspot for abolitionist activity. Many future black leaders and abolitionists were students at Oneida while Green was president. These include William Forten, Alexander Crummell

Alexander Crummell (March 3, 1819 – September 10, 1898) was a pioneering African-American minister, academic and African nationalist. Ordained as an Episcopal priest in the United States, Crummell went to England in the late 1840s to raise money ...

, Rev. Henry Highland Garnet

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an African-American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped as a child from slavery in Maryland with his family, he grew up in New York City. He was educat ...

, William G. Allen, Jermain Wesley Loguen

Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen (February 5, 1813 – September 30, 1872), born Jarm Logue, in slavery, was an African-American abolitionist and bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and an author of a slave narrative.

Biogr ...

, and Rev. Amos Noë Freeman.

In 1832, Green began to correspond with Gerrit Smith on the issue of black education. The two men became very close friends and much of what is known about Green is known from their letters. The two men worked together toward the goal of abolition. They continued correspondence until 1872, when they stopped writing because of long-held disagreements about civil government and political abolition.

Green was the first president of the American Anti-Slavery Society, formed in 1833 in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

. He was famous for refuting the arguments of men who used the Bible to defend slavery. In the late 1830s, Green focused most of his time contesting these arguments.

In 1835, Green and his friend Alvan Stewart convinced Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

to come to an organizational meeting for a New York Anti-Slavery Society, which they had called, in Utica. An anti-abolitionist mob, including Congressman Samuel Beardsley

Samuel Beardsley (February 6, 1790 – May 6, 1860) was an American attorney, judge and legislator from New York. During his career he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York Attorney General, United States ...

and other "principal citizens", "reviled the participants" and forced the convention to adjourn. At Smith's invitation they continued their meeting in his home town, nearby Peterboro, New York

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134.

...

.

Decline and closure of the Oneida Institute

The Panic of 1837 hit the Oneida Institute hard — its benefactors the Tappan brothers were ruined and unable to fulfill their pledges — and the college began to decline. Green also had begun to lose favor with conservative Presbyterians, which added to Oneida's troubles. Green led the secession of 59 church members from the Presbyterian church in Whitesboro over the issue of abolition. The seceders formed the Congregational Church in Whitesboro in 1837. Green was pastor of that church from 1843 to 1867. In 1844, the Oneida Institute was sold to theFree Will Baptist

Free Will Baptists are a group of General Baptist denominations of Christianity that teach free grace, free salvation and free will. The movement can be traced back to the 1600s with the development of General Baptism in England. Its formal est ...

s because of financial problems. After the Oneida Institute closed, Green became an active supporter of the Liberty Party. This was a third party that was completely devoted to the abolition of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. After the party failed to make an impact on American politics, Green became bitter with the democratic process. He did not like popular democracy and was in favor of an oligarchy or modified theocracy. Unlike many Liberty Party members, Green did not join the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

. He was worried that abolition would not be part of the major party principles.

After fellow abolitionists did not support his ideas about government, Green became resentful and did not travel far from Whitesboro. He supported his wife and children by farming and preaching to small groups of abolitionists.

He died on May 4, 1874 while giving a speech on temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

in Whitesboro.

Judgments about Green

His student William E. Allen said Green "is a profound scholar, an original thinker, and, better and greater than all these, a sincere and devoted Christian. To the strength and vigor of a man, he adds the gentleness and tenderness of a woman." Charles Stuart, another contemporary, seeking to raise funds for the Institute: "The labors of President Green in the antislavery cause, in the way of lectures, and the use of the press, have been various, indefatiguable, abundant, in the face of evils and proscriptions of various kinds, and eminently successful. He has all alone shone himself a man for emergencies. On such occasions, whoever else may have done it, Beriah Green has never been known to flee or flinch. The result is that the Institute has always been in the midst of a hard struggle — in establishing and sustaining itself as a manual labor college, second in defense of its course of study, and last, not least, in its vindication and defense of the rights of humanity. According to William Sernett, author of the only book on Green, "Green's erratic personality, acerbic tongue, and lack of political acumen were just as responsible for the closing of the institute as were problems with conservative trustees and the withdrawal of financial support from several key funding sources." "Although known during his lifetime as a 'fanatic' by many, Green has been more aptly described as a 'radical humanitarian'. Indeed, his life was a testimony to his beliefs. In the final analysis, he forfeited wealth, reputation, friends, and ultimately respectability for 'the cause'."Writings

* Books ** According to ''Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography

''Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography'' is a six-volume collection of biographies of notable people involved in the history of the New World. Published between 1887 and 1889, its unsigned articles were widely accepted as authoritative f ...

'', Green published in Albany, 1823, a ''History of the Quakers''. No other information has been found about this book.

**

**

* Sermons and essays

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

* Published letters

** Letter to Theodore Weld, October 1832

** Letter to Simeon Jocelyn Simeon Jocelyn (1799-1879) was a white pastor, abolitionist, and social activist for African-American civil rights and educational opportunities in New Haven, Connecticut, during the 19th century. He is known for his attempt to establish America's f ...

, November 5, 1832

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Greene, Jr. Beriah 1795 births 1874 deaths People from Preston, Connecticut American theologians 19th-century American historians 19th-century American male writers Middlebury College alumni American temperance activists Oneida Institute People from Hudson, Ohio Western Reserve College and Preparatory School faculty American Congregationalist ministers People from Whitesboro, New York People from Pawlet, Vermont People from Brandon, Vermont People from Kennebunk, Maine Underground Railroad people Congregationalist abolitionists Underground Railroad in New York (state) 19th-century American clergy American male non-fiction writers Historians from New York (state) Historians from Ohio Historians from Connecticut