Benjamin Thompson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, FRS (german:

In 1785, he moved to

In 1785, he moved to

Thompson also significantly improved the design of kilns used to produce

Thompson also significantly improved the design of kilns used to produce

Thompson endowed the

Thompson endowed the

Reichsgraf

Imperial Count (german: Reichsgraf) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. In the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly ( immediately) from the emperor, rather than from ...

von Rumford; March 26, 1753August 21, 1814) was an American-born British physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

whose challenges to established physical theory

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

were part of the 19th-century revolution in thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws ...

. He served as lieutenant-colonel of the King's American Dragoons

The King's American Dragoons were a British provincial military unit, raised for Loyalist service during the American Revolutionary War. They were founded by Colonel Benjamin Thompson, later Count Rumford, in 1781. They were initially formed fro ...

, part of the British Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

forces, during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. After the end of the war he moved to London, where his administrative talents were recognized when he was appointed a full colonel, and in 1784 he received a knighthood from King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

. A prolific designer, Thompson also drew designs for warships. He later moved to Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

and entered government service there, being appointed Bavarian Army Minister and re-organizing the army, and, in 1792, was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire

Imperial Count (german: Reichsgraf) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. In the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly ( immediately) from the emperor, rather than fro ...

.

Early years

Thompson was born in ruralWoburn, Massachusetts

Woburn ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 40,876 at the 2020 census. Woburn is located north of Boston. Woburn uses Massachusetts' mayor-council form of government, in which an elected mayor is ...

, on March 26, 1753; his birthplace is preserved as a museum. He was educated mainly at the village school, although he sometimes walked almost ten miles to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

with the older Loammi Baldwin

Colonel Loammi Baldwin (January 10, 1744 – October 20, 1807) was a noted American engineer, politician, and a soldier in the American Revolutionary War.

Baldwin is known as the Father of American Civil Engineering. His five sons, Cyrus ...

to attend lectures by Professor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

of Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

. At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to John Appleton, a merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

of nearby Salem. Thompson excelled at his trade, and coming in contact with refined and well educated people for the first time, adopted many of their characteristics including an interest in science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

. While recuperating in Woburn in 1769 from an injury, Thompson conducted experiments concerning the nature of heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

and began to correspond with Loammi Baldwin and others about them. Later that year he worked for a few months for a Boston shopkeeper and then apprenticed himself briefly, and unsuccessfully, to a doctor in Woburn.

Thompson's prospects were dim in 1772 but in that year they changed abruptly. He met, charmed and married a rich and well-connected heiress named Sarah Rolfe (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Walker). Her father was a minister, and her late husband left her property at Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the county seat, seat of Merrimack County, New Hampshire, Merrimack County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third larg ...

, then called Rumford. They moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsm ...

, and through his wife's influence with the governor, he was appointed a major in the New Hampshire Militia The New Hampshire Militia was first organized in 1631 and lasted until 1641, when the area came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts.

After New Hampshire became an separate colony again in 1679, New Hampshire Colonial Governor John Cutt reorgan ...

. Their child (also named Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pio ...

) was born in 1774.

American Revolutionary War

When theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began Thompson was a man of property and standing in New England and was opposed to the uprising. He was active in recruiting loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

to fight the rebels

Rebels may refer to:

* Participants in a rebellion

* Rebel groups, people who refuse obedience or order

* Rebels (American Revolution), patriots who rejected British rule in 1776

Film and television

* ''Rebels'' (film) or ''Rebelles'', a 2019 ...

. This earned him the enmity of the popular party, and a mob attacked Thompson's house. He fled to the British lines, abandoning his wife, as it turned out, permanently. Thompson was welcomed by the British to whom he gave valuable information about the American forces, and became an advisor to both General Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of the ...

and Lord George Germain

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville, PC (26 January 1716 – 26 August 1785), styled The Honourable George Sackville until 1720, Lord George Sackville from 1720 to 1770 and Lord George Germain from 1770 to 1782, was a British soldier and p ...

.

While working with the British armies in America he conducted experiments to measure the force of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, the results of which were widely acclaimed when published in 1781 in the ''Philosophical Transactions

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the first journa ...

'' of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. On the strength of this he arrived in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

at the end of the war with a reputation as a scientist.

Bavarian maturity

In 1785, he moved to

In 1785, he moved to Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

where he became an '' aide-de-camp'' to the Prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the princ ...

Charles Theodore. He spent eleven years in Bavaria, reorganizing the army and establishing workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

s for the poor. He also invented Rumford's Soup, a soup for the poor, and established the cultivation of the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

in Bavaria. He studied methods of cooking, heating, and lighting, including the relative costs and efficiencies of wax candles

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time.

A person who makes candl ...

, tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton fat. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, includ ...

candle

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time.

A person who makes candle ...

s, and oil lamp

An oil lamp is a lamp used to produce light continuously for a period of time using an oil-based fuel source. The use of oil lamps began thousands of years ago and continues to this day, although their use is less common in modern times. Th ...

s.

On Prince Charles' behalf he created the Englischer Garten

The ''Englischer Garten'' (, ''English Garden'') is a large public park in the centre of Munich, Bavaria, stretching from the city centre to the northeastern city limits. It was created in 1789 by Sir Benjamin Thompson (1753–1814), later Coun ...

in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

in 1789; it remains today and is known as one of the largest urban public parks in the world. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1789.

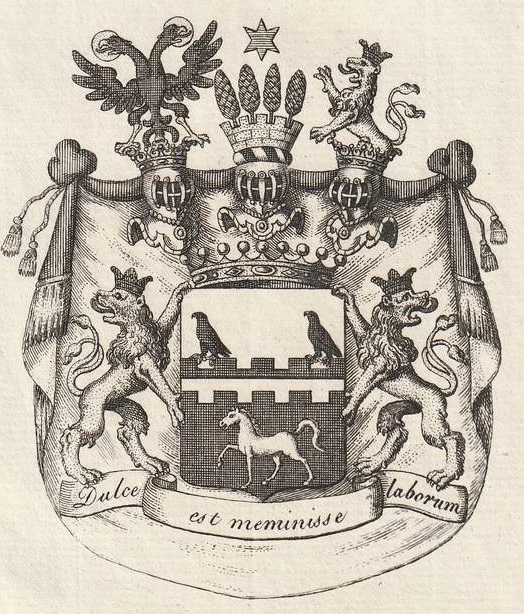

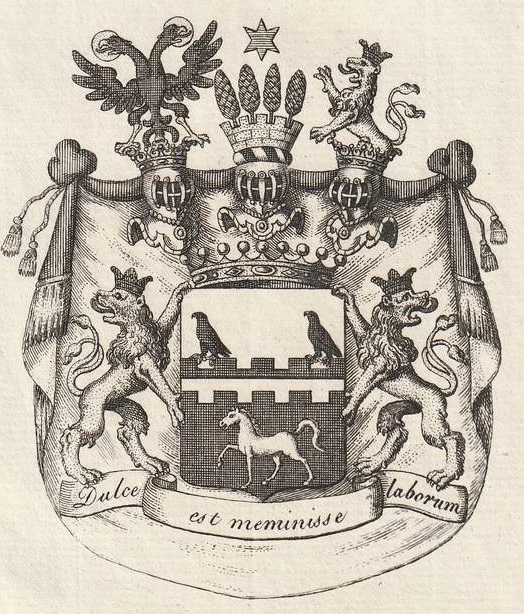

For his efforts, in 1791 Thompson was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire

Imperial Count (german: Reichsgraf) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. In the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly ( immediately) from the emperor, rather than fro ...

, becoming ''Reichsgraf

Imperial Count (german: Reichsgraf) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. In the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly ( immediately) from the emperor, rather than from ...

von Rumford'' (English: Imperial Count of Rumford). He took the name "Rumford" after the town of Rumford, New Hampshire, which was an older name for Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

where he had been married.

Science and engineering

Experiments on heat

His experiments on gunnery and explosives led to an interest in heat. He devised a method for measuring thespecific heat

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol ) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat t ...

of a solid substance but was disappointed when Johan Wilcke

Johan Carl Wilcke was a Swedish physicist.

Biography

Wilcke was born in Wismar, son of a clergyman who in 1739 was appointed second pastor of the German Church in Stockholm. He went to the German school in Stockholm and enrolled at the Univers ...

published his parallel discovery first.

Thompson next investigated the insulating properties of various materials, including fur, wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

and feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premie ...

s. He correctly appreciated that the insulating properties of these natural materials arise from the fact that they inhibit the convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the c ...

of air. He then made the somewhat reckless, and incorrect, inference that air and, in fact, all gases, were perfect non- conductors of heat. He further saw this as evidence of the argument from design

The teleological argument (from ; also known as physico-theological argument, argument from design, or intelligent design argument) is an argument for the existence of God or, more generally, that complex functionality in the natural world wh ...

, contending that divine providence

In theology, Divine Providence, or simply Providence, is God's intervention in the Universe. The term ''Divine Providence'' (usually capitalized) is also used as a title of God. A distinction is usually made between "general providence", which ...

had arranged for fur on animals in such a way as to guarantee their comfort.

In 1797, he extended his claim about non-conductivity to liquids. The idea raised considerable objections from the scientific establishment, John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry, and for his research into Color blindness, colour blindness, which ...

and John Leslie making particularly forthright attacks. Instrumentation far exceeding anything available in terms of accuracy and precision would have been needed to verify Thompson's claim. Again, he seems to have been influenced by his theological beliefs and it is likely that he wished to grant water a privileged and providential status in the regulation of human life.

He is considered the founder of the sous-vide

Sous vide (; French for 'under vacuum'), also known as low-temperature, long-time (LTLT) cooking, is a method of cooking in which food is placed in a plastic pouch or a glass jar and cooked in a water bath for longer than usual cooking times (usu ...

food preparation method owing to his experiment with a mutton shoulder. He described this method in one of his essays.

Mechanical equivalent of heat

Rumford's most important scientific work took place in Munich, and centred on the nature of heat, which he contended in "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction

''An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction'' is a scientific paper by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, which was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1798. The paper ...

" (1798) was not the caloric of then-current scientific thinking but a form of ''motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and m ...

''. Rumford had observed the frictional heat generated by boring cannon at the arsenal in Munich. Rumford immersed a cannon barrel in water and arranged for a specially blunted boring tool. He showed that the water could be boiled within roughly two and a half hours and that the supply of frictional heat was seemingly inexhaustible. Rumford confirmed that no physical change had taken place in the material of the cannon by comparing the specific heats of the material machined away and that remaining.

Rumford argued that the seemingly indefinite generation of heat was incompatible with the caloric theory. He contended that the only thing communicated to the barrel was motion.

Rumford made no attempt to further quantify the heat generated or to measure the mechanical equivalent of heat. Though this work met with a hostile reception, it was subsequently important in establishing the laws of conservation of energy

In physics and chemistry, the law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be ''conserved'' over time. This law, first proposed and tested by Émilie du Châtelet, means tha ...

later in the 19th century.

Calorific and frigorific radiation

He explained Pictet's experiment, which demonstrates the reflection of cold, by supposing that all bodies emit invisible rays, undulations in the ethereal fluid. He did experiments to support his theories of calorific and frigorific radiation and said the communication of heat was the net effect of calorific (hot) rays and frigorific (cold) rays and the rays emitted by the object. When an object absorbs radiation from a warmer object (calorific rays) its temperature rises, and when it absorbs radiation from a colder object (frigorific rays) its temperature falls. See note 8, "An enquiry concerning the nature of heat and the mode of its communication" Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, starting at page 112.Inventions and design improvements

Thompson was an active and prolific inventor, developing improvements for chimneys, fireplaces and industrial furnaces, as well as inventing the double boiler, akitchen range

A kitchen stove, often called simply a stove or a cooker, is a kitchen appliance designed for the purpose of cooking food. Kitchen stoves rely on the application of direct heat for the cooking process and may also contain an oven, used for baki ...

, and a drip coffeepot. He invented a percolating coffee pot following his pioneering work with the Bavarian Army, where he improved the diet of the soldiers as well as their clothes.

The Rumford fireplace

The Rumford fireplace is a tall, shallow fireplace designed by Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, an Anglo-American physicist best known for his investigations of heat. Its shallow, angled sides are designed to reflect heat into the room, and i ...

created a sensation in London when he introduced the idea of restricting the chimney opening to increase the updraught, which was a much more efficient way to heat a room than earlier fireplaces. He and his workers modified fireplaces by inserting bricks into the hearth to make the side walls angled, and added a choke to the chimney to increase the speed of air going up the flue. The effect was to produce a streamlined air flow, so all the smoke would go up into the chimney rather than lingering, entering the room, and often choking the residents. It also had the effect of increasing the efficiency of the fire, and gave extra control of the rate of combustion of the fuel, whether wood or coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

. Many fashionable London houses were modified to his instructions, and became smoke-free.

Thompson became a celebrity when news of his success spread. His work was also very profitable, and much imitated when he published his analysis of the way chimneys worked. In many ways, he was similar to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

, who also invented a new kind of heating stove.

The retention of heat was a recurring theme in his work, as he is also credited with the invention of thermal underwear

Long underwear, also called long johns or thermal underwear, is a style of two-piece underwear with long legs and long sleeves that is normally worn during cold weather. It is commonly worn by people under their clothes in cold countries.

In ...

.

Industrial furnaces

quicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "'' lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic m ...

, and Rumford furnace {{Short description, Kiln for the production of calcium oxide

A Rumford furnace is a kiln for the industrial scale production in the 19th century of calcium oxide, popularly known as quicklime or burnt lime. It was named after its inventor, Benjam ...

s were soon being constructed throughout Europe. The key innovation involved separating the burning fuel from the limestone, so that the lime produced by the heat of the furnace was not contaminated by ash from the fire.

Light and photometry

Rumford worked inphotometry Photometry can refer to:

* Photometry (optics), the science of measurement of visible light in terms of its perceived brightness to human vision

* Photometry (astronomy), the measurement of the flux or intensity of an astronomical object's electro ...

, the measurement of light. He made a photometer and introduced the standard candle

The cosmic distance ladder (also known as the extragalactic distance scale) is the succession of methods by which astronomers determine the distances to celestial objects. A ''direct'' distance measurement of an astronomical object is possible o ...

, the predecessor of the candela

The candela ( or ; symbol: cd) is the unit of luminous intensity in the International System of Units (SI). It measures luminous power per unit solid angle emitted by a light source in a particular direction. Luminous intensity is analogous t ...

, as a unit of luminous intensity

In photometry, luminous intensity is a measure of the wavelength-weighted power emitted by a light source in a particular direction per unit solid angle, based on the luminosity function, a standardized model of the sensitivity of the human e ...

. His standard candle was made from the oil of a sperm whale, to rigid specifications. He also published studies of "illusory" or subjective complementary colours, induced by the shadows created by two lights, one white and one coloured; these observations were cited and generalized by Michel-Eugène Chevreul as his "law of simultaneous colour contrast" in 1839.

Later life

After 1799, he divided his time between France and England. With SirJoseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

, he established the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

in 1799. The pair chose Sir Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for ...

as the first lecturer. The institution flourished and became world-famous as a result of Davy's pioneering research. His assistant, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, established the Institution as a premier research laboratory, and also justly famous for its series of public lectures popularizing science. That tradition continues to the present, and the Royal Institution Christmas lectures

The Royal Institution Christmas Lectures are a series of lectures on a single topic each, which have been held at the Royal Institution in London each year since 1825, missing 1939–1942 because of the Second World War. The lectures present sci ...

attract large audiences through their TV broadcasts.

Thompson endowed the

Thompson endowed the Rumford medal

The Rumford Medal is an award bestowed by Britain's Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe".

First awar ...

s of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

, and endowed the Rumford Chair of Physics at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

. In 1803, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for prom ...

, and as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

In 1804, he married Marie-Anne Lavoisier, the widow of the great French chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

''An Essay on Chimney Fire-Places; With Proposals for Improving Them, to Save Fuel, to Render Dwelling-Houses More Comfortable and Salubrious, and Effectually to Prevent Chimnies from Smoking. Illustrated with Engravings''

(1796).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume I, The Nature of Heat''

(1968).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume II, Practical Applications of Heat''

(1969).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume III, Devices and Techniques''

(1969).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume IV, Light and Armament''

(1970).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume V, Public Institutions''

(1970).

Rumford, Benjamin Thompson

'". (1753–1814)

An article not only detailing the Rumford fireplace, but also Rumford's life and other achievements. * *

Count Rumford's Birth Place and Museum

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thompson, Benjamin 1753 births 1814 deaths Loyalists in the American Revolution from New Hampshire American physicists British physicists Counts of the Holy Roman Empire Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Harvard University people People from the Duchy of Bavaria People of colonial Massachusetts People of colonial New Hampshire People from Woburn, Massachusetts Recipients of the Copley Medal 18th-century American people 19th-century American people 18th-century British people 19th-century British people Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Thermodynamicists

CNRS (

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

and continued his scientific work until his death on August 21, 1814. Thompson is buried in the small cemetery of Auteuil Auteuil may refer to:

Places

* Auteuil, Oise, a commune in France

* Auteuil, Paris, a neighborhood of Paris

** Auteuil, Seine, the former commune which was on the outskirts of Paris

* Auteuil, Quebec, a former city that is now a district within ...

in Paris, just across from Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transformation are name ...

. Upon his death, his daughter from his first marriage, Sarah Thompson, inherited his title as Countess Rumford.

Honours

* Colonel,King's American Dragoons

The King's American Dragoons were a British provincial military unit, raised for Loyalist service during the American Revolutionary War. They were founded by Colonel Benjamin Thompson, later Count Rumford, in 1781. They were initially formed fro ...

.

* Knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

ed, 1784.

* Count of the Holy Roman Empire

Imperial Count (german: Reichsgraf) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. In the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly ( immediately) from the emperor, rather than fro ...

, 1791.

* The crater Rumford on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

is named after him.

* Rumford baking powder

Baking powder is a dry chemical leavening agent, a mixture of a carbonate or bicarbonate and a weak acid. The base and acid are prevented from reacting prematurely by the inclusion of a buffer such as cornstarch. Baking powder is used to increas ...

(patented 1859) is named after him, having been invented by a former Rumford professor at Harvard University, Eben Norton Horsford (1818–1893), cofounder of the Rumford Chemical Works of East Providence, RI.

* Rumford Kitchen at the World's Fair in Chicago

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

, 1893.

* A street in the inner city of Munich is named after him.

* Rumford Street (and the nearby Rumford Place) in Liverpool, England, are so named due to a soup kitchen established to Count Rumford's plan which formerly stood on land adjacent to Rumford Street.

* : Order of the White Eagle (1789).

Bibliography

''An Essay on Chimney Fire-Places; With Proposals for Improving Them, to Save Fuel, to Render Dwelling-Houses More Comfortable and Salubrious, and Effectually to Prevent Chimnies from Smoking. Illustrated with Engravings''

(1796).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume I, The Nature of Heat''

(1968).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume II, Practical Applications of Heat''

(1969).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume III, Devices and Techniques''

(1969).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume IV, Light and Armament''

(1970).

''Collected Works of Count Rumford, Volume V, Public Institutions''

(1970).

See also

*History of thermodynamics

The history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general. Owing to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finel ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

* Eric Weisstein's World of Science. "Rumford, Benjamin Thompson

'". (1753–1814)

An article not only detailing the Rumford fireplace, but also Rumford's life and other achievements. * *

Count Rumford's Birth Place and Museum

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thompson, Benjamin 1753 births 1814 deaths Loyalists in the American Revolution from New Hampshire American physicists British physicists Counts of the Holy Roman Empire Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Harvard University people People from the Duchy of Bavaria People of colonial Massachusetts People of colonial New Hampshire People from Woburn, Massachusetts Recipients of the Copley Medal 18th-century American people 19th-century American people 18th-century British people 19th-century British people Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Thermodynamicists