Bengal Legislative Assembly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Bengal Legislative Assembly () was the largest legislature in British India, serving as the lower chamber of the legislature of

The assembly was the culmination of legislative development in Bengal which started in 1861 with the

The assembly was the culmination of legislative development in Bengal which started in 1861 with the

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, Ó”¼Ó”ŠÓ”éÓ”▓Ó”Š/Ó”¼Ó”ÖÓ¦ŹÓ”Ś, translit=B─üngl─ü/B├┤ng├┤, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

(now Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

and the Indian state of West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fou ...

). It was established under the Government of India Act 1935. The assembly played an important role in the final decade of undivided Bengal. The Leader of the House was the Prime Minister of Bengal. The assembly's lifespan covered the anti-feudal movement of the Krishak Praja Party, the period of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposing ...

, the Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution ( ur, , ''Qarardad-e-Lahore''; Bengali: Ó”▓Ó”ŠÓ”╣Ó¦ŗÓ”░ Ó”¬Ó¦ŹÓ”░Ó”ĖÓ¦ŹÓ”żÓ”ŠÓ”¼, ''Lahor Prostab''), also called Pakistan resolution, was written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and was presented by A. K. Fazlul ...

, the Quit India

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule i ...

movement, suggestions for a United Bengal and the partition of Bengal and partition of British India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

.

Many notable speeches were delivered by Bengali statesmen in this assembly. The records of the assembly's proceedings are preserved in the libraries of the Parliament of Bangladesh

The Jatiya Sangsad ( bn, Ó”£Ó”ŠÓ”żÓ¦ĆÓ”»Ó”╝ Ó”ĖÓ”éÓ”ĖÓ””, lit=National Parliament, translit=Jatiy├┤ S├┤ngs├┤d), often referred to simply as the ''Sangsad'' or JS and also known as the House of the Nation, is the supreme legislative body of B ...

and the West Bengal Legislative Assembly.

History

The assembly was the culmination of legislative development in Bengal which started in 1861 with the

The assembly was the culmination of legislative development in Bengal which started in 1861 with the Bengal Legislative Council

The Bengal Legislative Council ( was the legislative council of British Bengal (now Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal).

It was the legislature of the Bengal Presidency during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After reforms we ...

. The Government of India Act 1935 made the council the upper chamber, while the 250-seat legislative assembly was formed as the elected lower chamber. The act did not grant universal suffrage, instead in line with the Communal Award

The Communal Award was created by the British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald on 16 August 1932. Also known as the MacDonald Award, it was announced after the Round Table Conference (1930ŌĆō32) and extended the separate electorate to depressed Cl ...

, it created separate electorates as the basis of electing the assembly. The first elections took place in 1937. The Congress party emerged as the single largest party but refused to form a government due to its policy of boycotting legislatures. The Krishak Praja Party and Bengal Provincial Muslim League, supported by several independent legislators, formed the first government. A. K. Fazlul Huq became the first prime minister. Huq supported the League's Lahore Resolution in 1940, which called on the imperial government to include the eastern zone of British India in a future sovereign homeland for Muslims. The text of the resolution initially seemed to support the notion of an independent state in Bengal and Assam. The Krishak Praja Party implemented measures to curtail the influence of the landed gentry. Prime Minister Huq used both legal and administrative measures to relieve the debts of peasants and farmers. According to the historian Ayesha Jalal

Ayesha Jalal (Punjabi, ur, ) is a Pakistani-American historian who serves as the Mary Richardson Professor of History at Tufts University, and was the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

Family and early life

Ayesha Jala ...

, the Bengali Muslim population was keen for a Bengali-Assamese sovereign state and an end to the permanent settlement

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal, was an agreement between the East India Company and Bengali landlords to fix revenues to be raised from land that had far-reaching consequences for both agricultural met ...

.

In 1941, the League withdrew support for Huq after he joined the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

's defense council against the wishes of the League's president Jinnah. Jinnah felt the council's membership was detrimental to partitioning India; but Huq was joined on the council by the Prime Minister of the Punjab, Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan

'' Khan Bahadur'' Captain Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, (5 June 1892 ŌĆō 26 December 1942), also written Sikandar Hyat-Khan or Sikandar Hyat Khan, was an Indian politician and statesman from the Punjab who served as the Premier of the Punjab, amon ...

. In Bengal, Huq secured the support of Syama Prasad Mukherjee

Syama Prasad Mukherjee (6 July 1901 ŌĆō 23 June 1953) was an Indian politician, barrister and academician, who served as India's first Minister for Industry and Supply (currently known as Ministry of Commerce and Industry) in Jawaharlal Nehru' ...

, the leader of the Hindu Mahasabha, and formed a second coalition government. Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, a trusted confidante of Jinnah, became Leader of the Opposition. In 1943, the Huq ministry fell and Nazimuddin formed a Muslim League government.

Amid the outbreak of world war, Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, Ó”░Ó”¼Ó¦ĆÓ”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ŹÓ”░Ó”©Ó”ŠÓ”ź Ó”ĀÓ”ŠÓ”ĢÓ¦üÓ”░; 7 May 1861 ŌĆō 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

urged Prime Minister Nazimuddin to arrange for the release of Alex Aronson, a German citizen and Jewish

Jews ( he, ūÖų░ūöūĢų╝ūōų┤ūÖūØ, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

lecturer in Santiniketan

Santiniketan is a neighbourhood of Bolpur town in the Bolpur subdivision of Birbhum district in West Bengal, India, approximately 152 km north of Kolkata. It was established by Maharshi Devendranath Tagore, and later expanded by his son ...

who was interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

by the British colonial authority. Tagore had earlier requested the central home ministry of India to release Aronson but the request was turned down. Tagore then wrote a letter to Prime Minister Nazimuddin in Bengal. Prime Minister Nazimuddin intervened and secured the release of the lecturer.

Nazimuddin led conservative elements in the Bengal Provincial Muslim League. As World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposing ...

intensified and Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

attacked Bengal from Burma, the provincial government grappled with the Bengal famine of 1943. Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35ŌĆō37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

- Muslim relations continued to deteriorate, particularly during the Congress's Quit India movement. The next general election was delayed for two years. The Nazimuddin ministry became unpopular. Governor's rule was imposed between March 1945 and April 1946. Factional infighting within the Bengal Provincial Muslim League displaced the Nazimuddin faction; and the centre-left H. S. Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy ( bn, Ó”╣Ó¦ŗÓ”ĖÓ¦ćÓ”© Ó”ČÓ”╣Ó¦ĆÓ”” Ó”ĖÓ¦ŗÓ”╣Ó¦ŹŌĆīÓ”░Ó”ŠÓ”ōÓ”»Ó”╝Ó”ŠÓ”░Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦Ć; ur, ; 8 September 18925 December 1963) was a Bengali barrister and politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 t ...

-led faction took control of the provincial party.

The 1946 general election was won by the Bengal Provincial Muslim League. The League received its largest mandate in Bengal, compared to smaller mandates in other Muslim majority provinces in India. The result was interpreted as an equivocal approval of the Pakistan movement

The Pakistan Movement ( ur, , translit=TeßĖźr─½k-e-P─ükist─ün) was a political movement in the first half of the 20th century that aimed for the creation of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority areas of British India. It was connected to the per ...

. Suhrawardy was appointed prime minister. Suhrawardy's frosty relations with Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 ŌĆō 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

affected his ambitions of achieving a United Bengal, though both men wanted Calcutta to remain within an undivided Bengal. The Noakhali riots

The Noakhali riots were a series of semi-organized massacres, rapes and abductions, combined with looting and arson of Hindu properties, perpetrated by the Muslim community in the districts of Noakhali in the Chittagong Division of Bengal (n ...

and the violence of Direct Action Day

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946), also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hinduism in India, Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) ...

contributed to the government's stand on partitioning Bengal. Despite support from Bengali Hindu

Bengali Hindus ( bn, Ó”¼Ó”ŠÓ”ÖÓ¦ŹÓ”ŚÓ”ŠÓ”▓Ó¦Ć Ó”╣Ó”┐Ó”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ü/Ó”¼Ó”ŠÓ”ÖÓ”ŠÓ”▓Ó”┐ Ó”╣Ó”┐Ó”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ü, translit=B─üß╣ģg─ül─½ Hindu/B─üß╣ģ─üli Hindu) are an ethnoreligious population who make up the majority in the Indian states of West Ben ...

leaders like Sarat Chandra Bose

Sarat Chandra Bose ( Bengali: Ó”ČÓ”░Ó¦ÄÓ”ÜÓ”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ŹÓ”░ Ó”¼Ó”ĖÓ¦ü) (6 September 1889 ŌĆō 20 February 1950) was an Indian barrister and independence activist.

Early life

He was born to Janakinath Bose (father) and Prabhabati Devi in Cutta ...

and the Governor of Bengal, Suhrawardy's proposals were not heeded by Earl Mountbatten and Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 ŌĆō 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democratŌĆö

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

. The Hindu Mahasabha's legislators in the assembly demanded the partition of Bengal.

Eve of partition

On 20 June 1947, the Bengal Legislative Assembly met to decide on the partition of Bengal. At the preliminary joint meeting, it was decided by 120 votes to 90 that the province, if it remained united, should join the " new Constituent Assembly" (Pakistan). At a separate meeting of legislators from West Bengal, it was decided by 58 votes to 21 that the province should be partitioned and that West Bengal should join the " existing Constituent Assembly" (India). At a separate meeting of legislators from East Bengal, it was decided by 106 votes to 35 that the province should not be partitioned and 107 votes to 34 that East Bengal should join the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in the event of partition. On 6 July 1947, the region of Sylhet in Assam voted in areferendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

to join East Bengal.

Seats

The allocation of 250 seats in the assembly was based on the communal award. It is illustrated in the following. * General elected seats- 78 * Muslim electorate seats- 117 ** Urban seats- 6 ** Rural seats- 111 *Anglo-Indian

Anglo-Indian people fall into two different groups: those with mixed Indian and British ancestry, and people of British descent born or residing in India. The latter sense is now mainly historical, but confusions can arise. The '' Oxford English ...

electorate seats- 3

* European electorate seats- 11

* Indian Christian electorate seats- 2

* Commerce, Industries and Planting seats- 19

** Port of Calcutta

Port of Kolkata or Kolkata Port, officially known as Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port Trust (formerly Kolkata Port Trust), is the only riverine major port of India, located in the city of Kolkata, West Bengal, around from the sea. It is the olde ...

** Port of Chittagong

The Chittagong Port ( bn, Ó”ÜÓ”¤Ó¦ŹÓ”¤Ó”ŚÓ¦ŹÓ”░Ó”ŠÓ”« Ó”¼Ó”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó”░) is the main seaport of Bangladesh. Located in Bangladesh's port city of Chittagong and on the banks of the Karnaphuli River, the port handles over 90 percent of Bangladesh's ...

** Bengal Chamber of Commerce

The Bengal Chamber of Commerce and Industry is a non-governmental trade association and advocacy group based in West Bengal, India. It is the oldest chamber of commerce in India, and one of the oldest in Asia.

Established in 1853, finding its o ...

** Jute Interest

** Tea Interest

** Railways

** Traders Associations

** Others

* Zamindar

A zamindar ( Hindustani: Devanagari: , ; Persian: , ) in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semiautonomous ruler of a province. The term itself came into use during the reign of Mughals and later the British had begun using it as ...

seats- 5

* Labour representatives- 8

* Education seats- 2

** University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta (informally known as Calcutta University; CU) is a public collegiate state university in India, located in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Considered one of best state research university all over India every year, ...

- 1

** University of Dacca

The University of Dhaka (also known as Dhaka University, or DU) is a public research university located in Dhaka, Bangladesh. It is the oldest university in Bangladesh. The university opened its doors to students on July 1st 1921. Currently it ...

- 1

* Women seats- 5

** General electorate- 2

** Muslim electorate- 2

** Anglo-Indian electorate- 1

Elections

The following results are recorded by theAsiatic Society of Bangladesh

The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh is a non political and non profit research organisation registered under both Society Act of 1864 and NGO Bureau, Government of Bangladesh. The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh was established as the Asiatic Society ...

.

1937 general election

1946 general election

Ministries

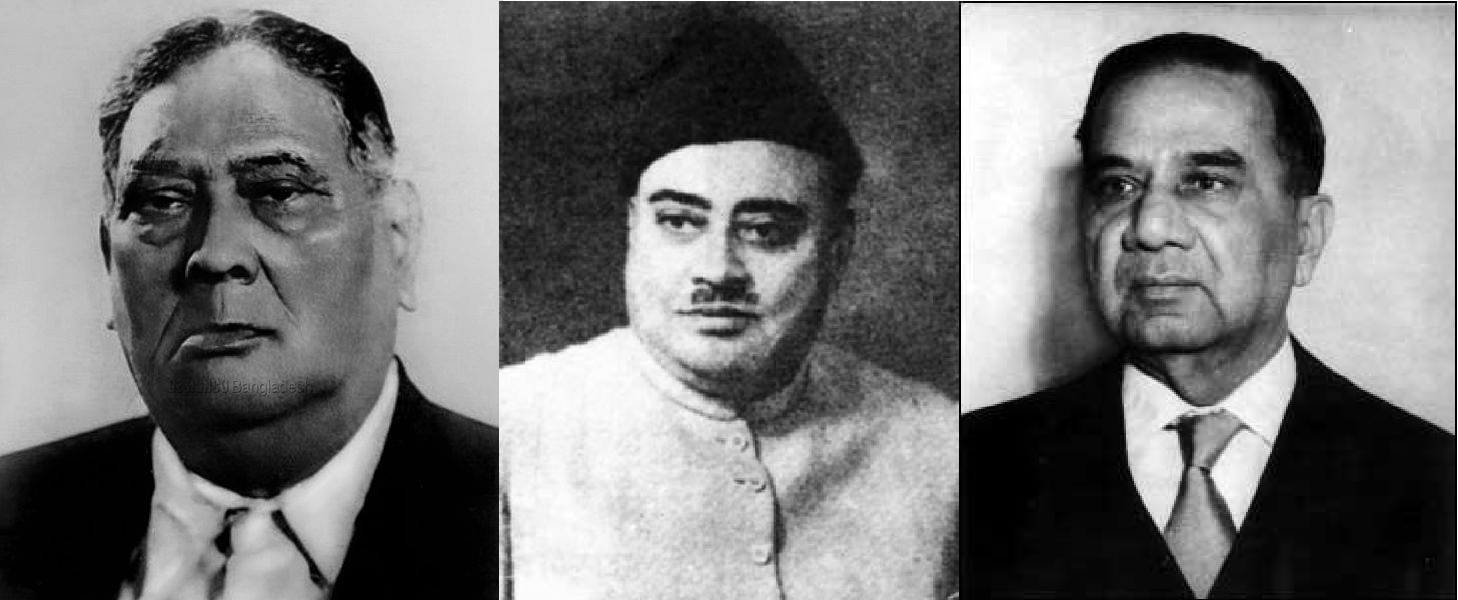

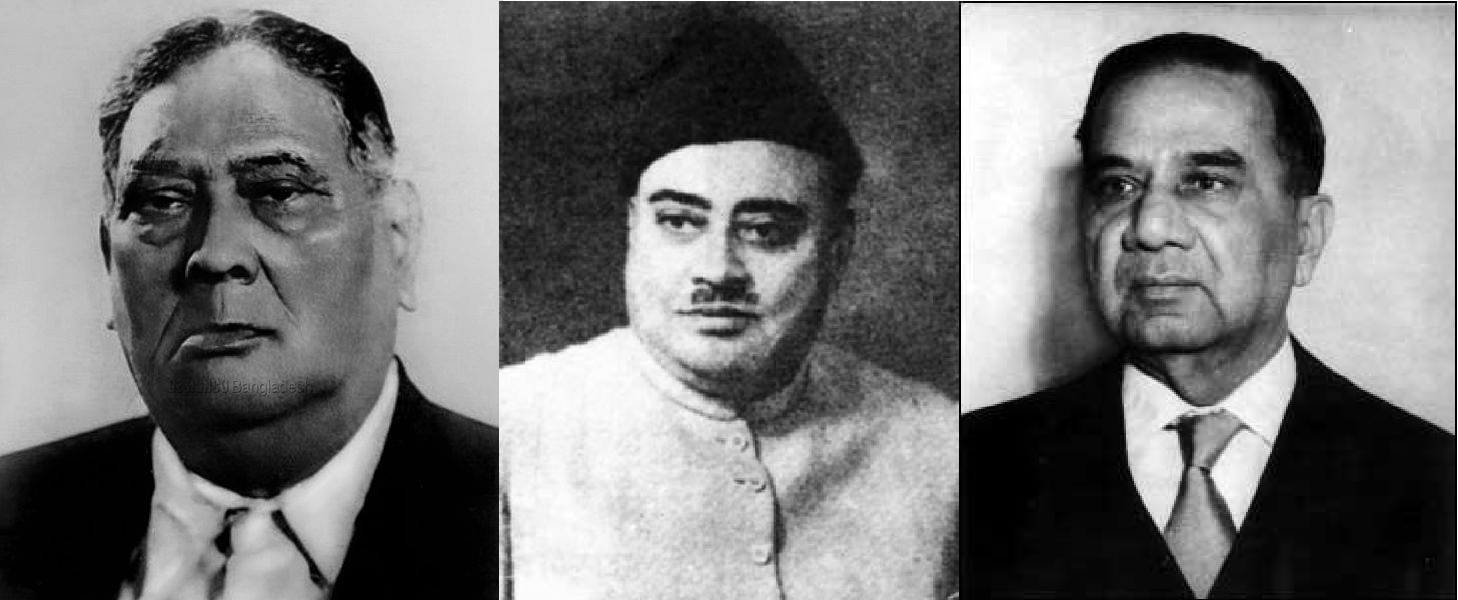

First Huq ministry

The first ministry was formed by Prime Minister A. K. Fazlul Huq lasted between 1 April 1937 and 1 December 1941. Huq himself held the portfolio of Education, SirKhawaja Nazimuddin

Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin ( bn, Ó”¢Ó”ŠÓ”£Ó”Š Ó”©Ó”ŠÓ”£Ó”┐Ó”«Ó¦üÓ””Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ĆÓ”©; ur, ; 19 July 1894 ŌĆō 22 October 1964) was a Pakistani politician and one of the leading founding fathers of Pakistan. He is noted as being the first Bengali to ha ...

was Home Minister, H. S. Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy ( bn, Ó”╣Ó¦ŗÓ”ĖÓ¦ćÓ”© Ó”ČÓ”╣Ó¦ĆÓ”” Ó”ĖÓ¦ŗÓ”╣Ó¦ŹŌĆīÓ”░Ó”ŠÓ”ōÓ”»Ó”╝Ó”ŠÓ”░Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦Ć; ur, ; 8 September 18925 December 1963) was a Bengali barrister and politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 t ...

was Commerce and Labour Minister, Nalini Ranjan Sarkar was Finance Minister, Sir Bijay Prasad Singh Roy was Revenue Minister, Khwaja Habibullah

Nawab Khwaja Habibullah Bahadur (26 April 1895 ŌĆō 21 November 1958) was the fifth Nawab of Dhaka. He was the son of Nawab Sir Khwaja Salimullah Bahadur. Under Habibullah's rule, the Dhaka Nawab Estate went into decline until its actual relinqui ...

was Agriculture and Industry Minister, Srish Chandra Nandy was Irrigation, Works and Communications Minister, Prasana Deb Raikut was Forest and Excise Minister, Mukunda Behari Mallick was Cooperative, Credit and Rural Indebtedness Minister, Nawab Musharraf Hussain was Judicial and Legislature Minister and Syed Nausher Ali was Public Health and Local Self Government Minister.

Second Huq ministry

The second Huq ministry lasted between 12 December 1941 and 29 March 1943. It was known as the Shyama-Huq coalition.Nazimuddin ministry

The Nazimuddin ministry lasted between 29 April 1943 and 31 March 1945.Suhrawardy ministry

The Suhrawardy ministry lasted between 23 April 1946 and 14 August 1947. Suhrawardy was himself Home Minister.Mohammad Ali of Bogra

Sahibzada Syed Mohammad Ali Chowdhury ( bn, Ó”ĖÓ¦łÓ”»Ó”╝Ó”” Ó”«Ó¦ŗÓ”╣Ó”ŠÓ”«Ó¦ŹÓ”«Ó”” Ó”åÓ”▓Ó¦Ć Ó”ÜÓ¦īÓ”¦Ó¦üÓ”░Ó¦Ć; Urdu: ž│█īž» ┘ģžŁ┘ģž» ž╣┘ä█ī ┌å┘ł█üž»ž▒█ī), more commonly known as Mohammad Ali Bogra ( bn, Ó”«Ó¦ŗÓ”╣Ó”ŠÓ”«Ó¦ŹÓ”«Ó”” Ó”åÓ”▓Ó¦Ć Ó ...

was Finance, Health and Local Self Government Minister. Syed Muazzemuddin Hossain was Education Minister. Ahmed Hossain was Agriculture, Forest and Fisheries Minister. Nagendra Nath Roy was Judicial and Legislative Minister. Abul Fazal Muhammad Abdur Rahman was Cooperatives and Irrigation Minister. Abul Gofran was Civil Supplies Minister. Tarak Nath Mukherjee was Waterways Minister. Fazlur Rahman was Land Minister. Dwarka Nath Barury was Works Minister.

Speaker of the assembly

The legislative assembly elected its own Speaker. Sir Azizul Haque was the first speaker of the assembly. His successors included Syed Nausher Ali andNurul Amin

Nurul Amin ( bn, Ó”©Ó¦üÓ”░Ó¦üÓ”▓ Ó”åÓ”«Ó”┐Ó”©; ur, ; 15 July 1893 ŌĆō 2 October 1974) was a prominent Pakistani leader, and a jurist who served as the eighth prime minister of Pakistan and as the first and only vice president of Pakistan. H ...

.

See also

*House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

* British Indian Empire

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''r─üj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himse ...

References

{{reflist 1937 establishments in British India 1947 disestablishments in British India Bengal Presidency West Bengal Legislative Assembly Historical legislatures in Bangladesh Historical state legislatures in India