Ben Gascoigne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sidney Charles Bartholemew "Ben" Gascoigne (11 November 191525 March 2010) was a New Zealand-born optical astronomer and expert in

In 1949, the Gascoignes' third child, daughter Hester, was born. Like many Observatory personnel, the Gascoignes lived in a staff residence on

In 1949, the Gascoignes' third child, daughter Hester, was born. Like many Observatory personnel, the Gascoignes lived in a staff residence on

In 1963 Gascoigne published an article in the journal ''Nature'' titled "Towards a Southern Commonwealth Observatory".

Gascoigne was then given a significant opportunity that became the focus of the remainder of his paid academic career: to help establish one of the world's largest optical telescopes, at Siding Spring. In the early 1960s, the Australian and British governments proposed a partnership to build a joint optical telescope facility, and Gascoigne was among the experts involved. Former Mount Stromlo director and now head of the Greenwich observatory, Richard Woolley, was prominent in supporting the project from the British end. In 1967, the two governments formally agreed to collaborate on the construction of a large telescope, to be known as the

In 1963 Gascoigne published an article in the journal ''Nature'' titled "Towards a Southern Commonwealth Observatory".

Gascoigne was then given a significant opportunity that became the focus of the remainder of his paid academic career: to help establish one of the world's largest optical telescopes, at Siding Spring. In the early 1960s, the Australian and British governments proposed a partnership to build a joint optical telescope facility, and Gascoigne was among the experts involved. Former Mount Stromlo director and now head of the Greenwich observatory, Richard Woolley, was prominent in supporting the project from the British end. In 1967, the two governments formally agreed to collaborate on the construction of a large telescope, to be known as the

photometry Photometry can refer to:

* Photometry (optics), the science of measurement of visible light in terms of its perceived brightness to human vision

* Photometry (astronomy), the measurement of the flux or intensity of an astronomical object's electrom ...

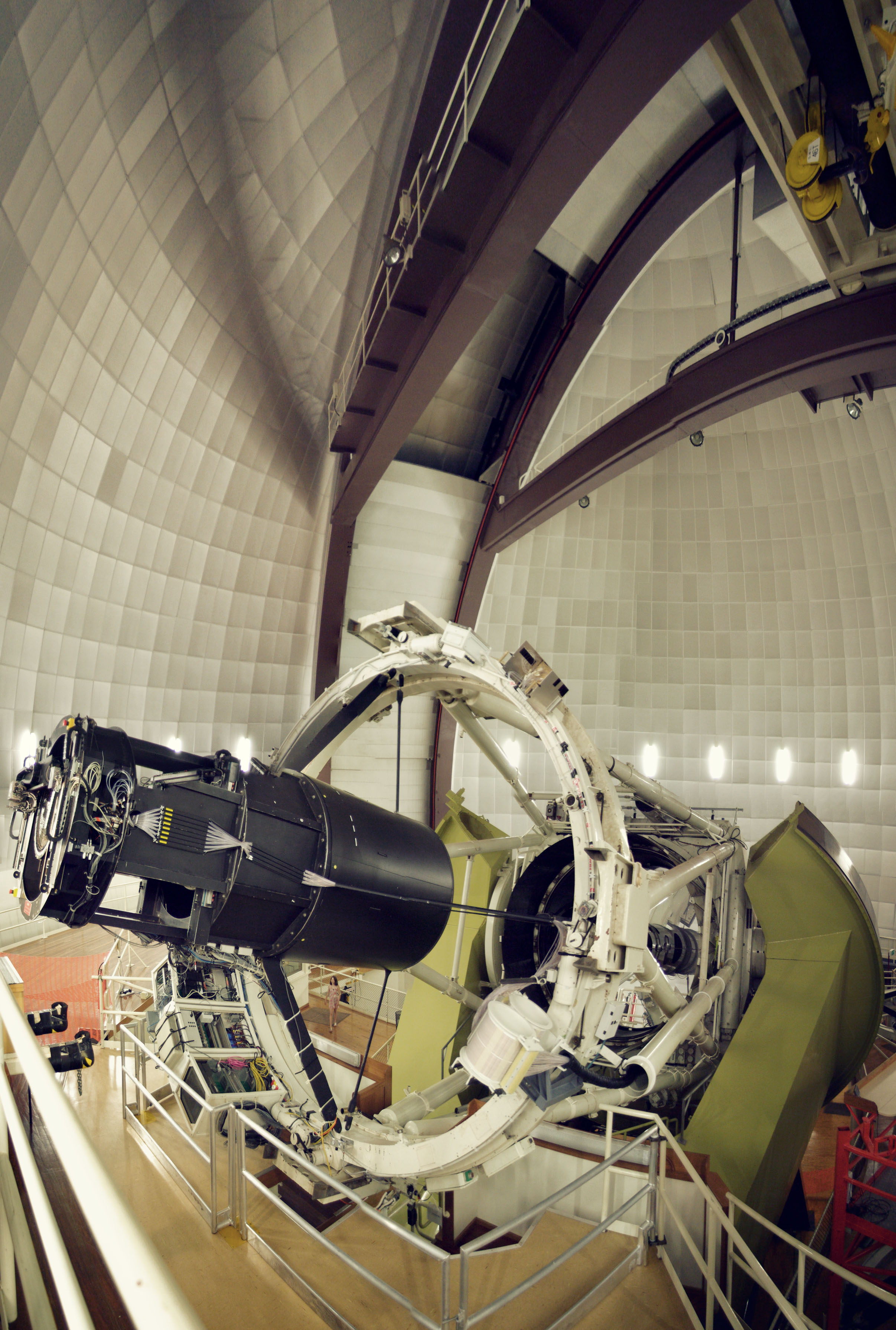

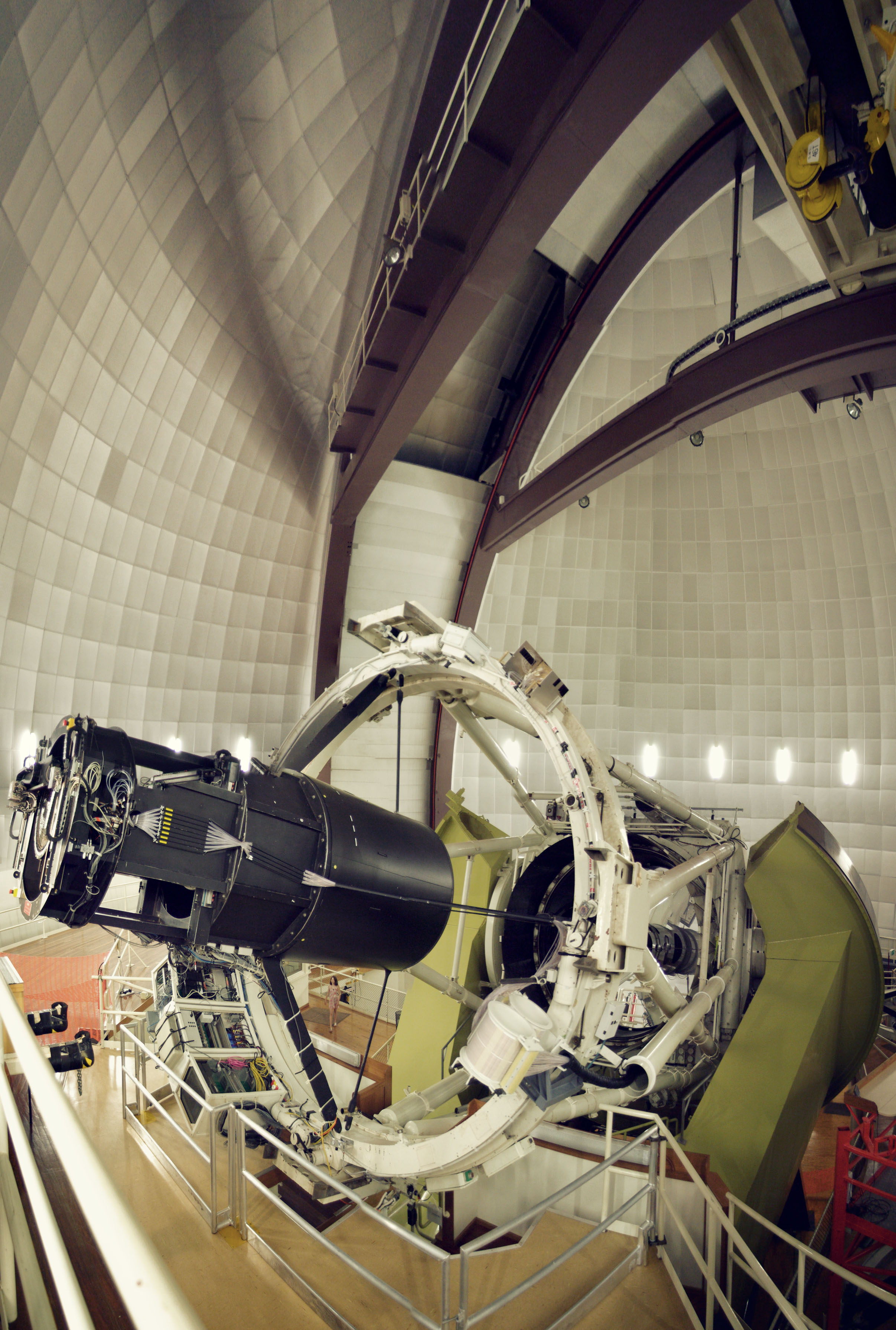

who played a leading role in the design and commissioning of Australia's largest optical telescope, the Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 20 ...

, which for a time was one of the world's most important astronomical facilities. Born in Napier, New Zealand

Napier ( ; mi, Ahuriri) is a city on the eastern coast of the North Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Hawke's Bay Region, Hawke's Bay region. It is a beachside city with a Napier Port, seaport, known for its sunny climate, esplanade lin ...

, Gascoigne trained in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The List of New Zealand urban areas by population, most populous urban area in the country and the List of cities in Oceania by po ...

and at the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, before moving to Australia during World War II to work at the Commonwealth Solar Observatory

Mount Stromlo Observatory located just outside Canberra, Australia, is part of the Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Australian National University (ANU).

History

The observatory was established in 1924 as The Commonwea ...

at Mount Stromlo

Mount Stromlo (formerly Mount Strom ) is a mountain with an elevation of that is situated in the Australian Capital Territory, Australia. The mountain is most notable as the location of the Mount Stromlo Observatory. The mountain forms part ...

in Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

. He became skillful in the design and manufacture of optical device

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

s such as telescope elements.

Following the war, Gascoigne and astronomer Gerald Kron used newly modernised telescopes at Mount Stromlo to determine that the distance between our galaxy and the Magellanic Cloud

The Magellanic Clouds (''Magellanic system'' or ''Nubeculae Magellani'') are two irregular galaxy, irregular dwarf galaxy, dwarf galaxy morphological classification, galaxies in the southern celestial hemisphere. Orbiting the Milky Way galaxy, t ...

dwarf galaxies had been underestimated by a factor of two. Because this measurement was used to calibrate other distances in astronomy, the result effectively doubled the estimated size of the universe. They also found that star formation in the Magellanic Clouds had occurred more recently than in the Milky Way; this overturned the prevailing view that both had evolved in parallel. A major figure at Mount Stromlo Observatory

Mount Stromlo Observatory located just outside Canberra, Australia, is part of the Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Australian National University (ANU).

History

The observatory was established in 1924 as The Commonwea ...

, Gascoigne helped it develop from a solar observatory to a centre of stellar and galactic research, and was instrumental in the creation of its field observatory in northern New South Wales, Siding Spring Observatory

Siding Spring Observatory near Coonabarabran, New South Wales, Australia, part of the Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics (RSAA) at the Australian National University (ANU), incorporates the Anglo-Australian Telescope along with a coll ...

. When the British and Australian governments agreed to jointly build the Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 20 ...

at Siding Spring, Gascoigne was involved from its initial conception and throughout its lengthy commissioning, taking its first photograph. Gascoigne was made an Officer of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Gove ...

for his contributions to astronomy and to the Anglo-Australian Telescope.

Gascoigne and his wife, artist Rosalie Gascoigne

Rosalie Norah King Gascoigne (née Walker; 25 January 191725 October 1999) was a New Zealand-born Australian sculptor and assemblage artist. She showed at the Venice Biennale in 1982, becoming the first female artist to represent Australia there ...

, had three children. After he retired, Gascoigne wrote several works on Australian astronomical history. He acted as Rosalie's photographer and assistant, using his technical skills to make her artworks resilient for public display.

Early life

Gascoigne's parents met and married inLevin, New Zealand

Levin (; mi, Taitoko) is the largest town and seat of the Horowhenua District, in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand's North Island. It is located east of Lake Horowhenua, around 95 km north of Wellington and 50 km southw ...

, just before the First World War. They soon moved to Napier, where Gascoigne was born in 1915. He attended Auckland Grammar School

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

, and won a scholarship to Auckland University College (now the University of Auckland

, mottoeng = By natural ability and hard work

, established = 1883; years ago

, endowment = NZD $293 million (31 December 2021)

, budget = NZD $1.281 billion (31 December 2021)

, chancellor = Cecilia Tarrant

, vice_chancellor = Dawn F ...

) a year before he was due to finish high school. Faced with a choice between studying history or the sciences, he chose the latter because he had a severe stammer and thought that it would be less of an impediment. He completed both a Bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

and a Master's qualification in science, securing Honours in both mathematics and physics, finishing his studies in 1937. Despite these achievements, he did not consider himself to be practically trained, saying: "I was still very much a theorist, with no practical physics at all. The professor in Auckland used to wince when I walked past the cupboard in which the good instruments were kept!"

In 1933, while studying at the university, he met his future wife Rosalie Norah King Walker, although they did not marry for another decade. Rosalie completed a Bachelor of Arts while Gascoigne was studying in Auckland; she also studied at Auckland's teacher training college while he was in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

.

Although Gascoigne had always intended to study mathematics at Cambridge, an event occurred that significantly shaped his career. In 1931, an earthquake in New Zealand killed Michael Hiatt Baker, a young traveller from Bristol, and his parents established a postgraduate scholarship in his memory, for study at the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, which Gascoigne won and took up in 1938. During his thesis studies at Bristol, Gascoigne developed a diffraction

Diffraction is defined as the interference or bending of waves around the corners of an obstacle or through an aperture into the region of geometrical shadow of the obstacle/aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a s ...

theory of the Foucault test that is used for evaluating the shape of large telescope mirrors. He completed his doctorate in physics in 1941, but by then war had broken out in Europe, and he had already returned to New Zealand on the last available ship.

War service 1940–1945

Returning to a job in the physics department at Auckland, Gascoigne worked on militaryoptics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

, developing gun sight

A sight is an aiming device used to assist in visually aligning ranged weapons, surveying instruments or optical illumination equipments with the intended target. Sights can be a simple set or system of physical markers that have to be aligne ...

s and rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

s, although he did not remain there for long. Richard van der Riet Woolley

Sir Richard van der Riet Woolley Officer of the Order of the British Empire, OBE Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (24 April 1906 – 24 December 1986) was an English astronomer who became the eleventh Astronomer Royal. His mother's maiden n ...

, director of the Commonwealth Solar Observatory in Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

(now Mount Stromlo Observatory

Mount Stromlo Observatory located just outside Canberra, Australia, is part of the Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Australian National University (ANU).

History

The observatory was established in 1924 as The Commonwea ...

), sought out Gascoigne because his "experience in optical work asunique" and Gascoigne was "trained in a way that no one else in Australia has been qualified". When in 1941 Gascoigne was offered a research fellowship by Woolley, he moved to Canberra. The Solar Observatory staff had similar responsibilities to those Gascoigne had held in New Zealand. His first task was to design an anti-aircraft gun sight, and he was also involved in a range of other military optical projects. In 1944, the Melbourne Observatory, home to the Commonwealth Time Service, was closed. Gascoigne reestablished the Time Service at Mount Stromlo, using two Shortt-Synchronome clocks and astronomical observing equipment that he and his colleagues adapted; the Time Service remained at Mount Stromlo until 1968. The knowledge and experience Gascoigne gained during the war proved valuable. He was at the only facility in Australia where optical work could be done, from design and manufacture to assembly and testing. Gascoigne developed a wide range of skills and "finished up quite practical, especially with a screwdriver."

A decade after Gascoigne first met Rosalie in New Zealand, she travelled to Canberra, and on 9 January 1943 they were married. Their first son, Martin, was born in November, and their second, Thomas, was born in 1945.

Mount Stromlo

Following the end of the war Woolley redirected the Commonwealth Observatory from solar research towards the study of stars and galaxies. It took time to get the old and unused telescopes back up to working condition: they had to be overhauled and refurbished, and in one case rebuilt from scrap. Woolley got funding approval from thePrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

for construction of a 74-inch telescope, but it would not be finished for years. Gascoigne began to work in the nascent field of photoelectric photometry Photometry can refer to:

* Photometry (optics), the science of measurement of visible light in terms of its perceived brightness to human vision

* Photometry (astronomy), the measurement of the flux or intensity of an astronomical object's electrom ...

, using electrical devices to measure the brightness of stars more accurately than had been possible using photographic techniques. In 1951, with equipment brought by visiting astronomer Gerald Kron

Gerald Kron (April 6, 1913 – April 9, 2012) was an American astronomer who was one of the pioneers of high-precision photometry with photoelectric instrumentation. He discovered the first starspot and made the first photometric observation of a ...

from California's Lick Observatory

The Lick Observatory is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by the University of California. It is on the summit of Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California, United States. The observatory is managed by th ...

, he observed Cepheid variable

A Cepheid variable () is a type of star that pulsates radially, varying in both diameter and temperature and producing changes in brightness with a well-defined stable period and amplitude.

A strong direct relationship between a Cepheid varia ...

stars, which are used to measure astronomical distances. Granted nine months of observing time on the Observatory's Reynolds 30-inch reflector telescope

A reflecting telescope (also called a reflector) is a telescope that uses a single or a combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century by Isaac Newton as an alternati ...

– an extraordinary opportunity – Gascoigne, Kron and others surveyed Cepheid stars in both the Small Magellanic Cloud

The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), or Nubecula Minor, is a dwarf galaxy near the Milky Way. Classified as a dwarf irregular galaxy, the SMC has a D25 isophotal diameter of about , and contains several hundred million stars. It has a total mass of ...

and, later, the Large Magellanic Cloud

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), or Nubecula Major, is a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. At a distance of around 50 kiloparsecs (≈160,000 light-years), the LMC is the second- or third-closest galaxy to the Milky Way, after the ...

. They also examined the colours of star cluster

Star clusters are large groups of stars. Two main types of star clusters can be distinguished: globular clusters are tight groups of ten thousand to millions of old stars which are gravitationally bound, while open clusters are more loosely clust ...

s in the Small Cloud.

The research produced remarkable results: "it meant that the Magellanic Clouds were twice as far away as was previously thought, and if then the baseline is twice as long, the size of the universe is doubled." It also showed that star formation in the Magellanic Clouds had occurred more recently than in the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye ...

. The results overturned the prevailing view that our galaxy and the Magellanic Clouds had evolved in parallel.Haynes ''et al.'', p. 168 Gascoigne said of his work:

Subsequent research confirmed what were described as pioneering results, arrived at through very innovative techniques.

Mount Stromlo

Mount Stromlo (formerly Mount Strom ) is a mountain with an elevation of that is situated in the Australian Capital Territory, Australia. The mountain is most notable as the location of the Mount Stromlo Observatory. The mountain forms part ...

, which was a long difficult trip away from Canberra. It was cold and lonely, particularly for Rosalie, but they enjoyed the outdoors, and the landscape inspired Rosalie's creativity and later her artistic career. In 1960 they relocated to Deakin in suburban Canberra, and in the late 1960s they moved to another suburb, Pearce Pearce may refer to:

Places

*Pearce, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb

*Division of Pearce, an electoral division in Western Australia

*Pearce, Arizona, United States, an unincorporated community

*RAAF Base Pearce, the main Royal Australian Ai ...

.

In 1957, administrative responsibility for the Commonwealth Observatory was transferred from the Australian Government's Department of the Interior to the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

(ANU), a move supported by both its director, Richard Woolley, and Gascoigne. This was an era of significant change at Mount Stromlo: in January 1956 Woolley had resigned as director of Mount Stromlo to take up a position as Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

and director of the Royal Observatory Greenwich

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a c ...

. He was replaced by Dutch-American Bart Bok

Bartholomeus Jan "Bart" Bok (April 28, 1906 – August 5, 1983) was a Dutch-American astronomer, teacher, and lecturer. He is best known for his work on the structure and evolution of the Milky Way galaxy, and for the discovery of Bok globules, ...

, whom Gascoigne liked and under whose directorship he played a significant role. Also in 1957, the Mount Stromlo team began searching for a new field observatory site, due to the increased light pollution

Light pollution is the presence of unwanted, inappropriate, or excessive use of artificial Visible spectrum, lighting. In a descriptive sense, the term ''light pollution'' refers to the effects of any poorly implemented lighting, during the day ...

from Canberra's growth. The search was vigorously promoted by Bok, and after an examination of 20 possible locations, two were shortlisted: Mount Bingar, near Griffith, New South Wales

Griffith is a major regional city in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area that is located in the north-western part of the Riverina region of New South Wales, known commonly as the food bowl of Australia. It is also the seat of the City of Griffith ...

, and Siding Spring, near Coonabarabran, New South Wales

Coonabarabran

is a town in Warrumbungle Shire that sits on the divide between the Central West (New South Wales), Central West and North West Slopes regions of New South Wales, Australia. At the 2016 Australian census, 2016 census, the town had ...

. Gascoigne was one of a group of scientists who visited Siding Spring Mountain as part of the search, and he was one of those who advocated this choice:

In 1962, Siding Spring was selected, and by 1967 Siding Spring Observatory

Siding Spring Observatory near Coonabarabran, New South Wales, Australia, part of the Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics (RSAA) at the Australian National University (ANU), incorporates the Anglo-Australian Telescope along with a coll ...

was fully operational.

At the end of Woolley's directorship, the 74-inch telescope he had initiated finally came online. Gascoigne, looking for a new research project and keen to use the new telescope, took up the study of globular cluster

A globular cluster is a spheroidal conglomeration of stars. Globular clusters are bound together by gravity, with a higher concentration of stars towards their centers. They can contain anywhere from tens of thousands to many millions of membe ...

s, compact groups of tens of thousands of ancient stars of similar age. With a new design of photometer

A photometer is an instrument that measures the strength of electromagnetic radiation in the range from ultraviolet to infrared and including the visible spectrum. Most photometers convert light into an electric current using a photoresistor, ph ...

, he was able to measure the exceptionally faint stars in these clusters. Gascoigne determined that the clusters in the Magellanic Clouds were both young and old, and had quite different characteristics to those in the Milky Way: this information was important for modelling the evolution of galaxies.

In 1963, Gascoigne developed a device, known as an optical corrector plate, which allowed wide field photography on the new 40-inch telescope at Siding Spring. Such corrector plates were subsequently used on many telescopes and became known as Gascoigne correctors. During this period he was also active in supporting the establishment of a national research organisation for astronomers, the Astronomical Society of Australia

The Astronomical Society of Australia (ASA) is the professional body representing astronomers in Australia. Established in 1966, it is incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory. Membership of the ASA is open to people "capable of contributi ...

. It held its first meeting in 1966, and Gascoigne was made its first vice-president.

When Bok retired as Stromlo's director in early 1966, Gascoigne became acting director for three months until the arrival of Bok's replacement, American astronomer Olin J. Eggen. Like Bok Eggen was a productive scientist, but he was "enigmatic", "somewhat gruff" and selective in the friendships he formed. Although Eggen and Gascoigne had previously collaborated on research projects, when Eggen arrived to take up the post, he and Gascoigne did not get on well, in contrast to Gascoigne's relationships with other astronomers. Gascoigne said of Eggen: "he made it clear I had no further part in running the Observatory. I was given no information, saw no documents, attended no meetings, and was asked for no advice, not even in optical matters."

Anglo-Australian Telescope

In 1963 Gascoigne published an article in the journal ''Nature'' titled "Towards a Southern Commonwealth Observatory".

Gascoigne was then given a significant opportunity that became the focus of the remainder of his paid academic career: to help establish one of the world's largest optical telescopes, at Siding Spring. In the early 1960s, the Australian and British governments proposed a partnership to build a joint optical telescope facility, and Gascoigne was among the experts involved. Former Mount Stromlo director and now head of the Greenwich observatory, Richard Woolley, was prominent in supporting the project from the British end. In 1967, the two governments formally agreed to collaborate on the construction of a large telescope, to be known as the

In 1963 Gascoigne published an article in the journal ''Nature'' titled "Towards a Southern Commonwealth Observatory".

Gascoigne was then given a significant opportunity that became the focus of the remainder of his paid academic career: to help establish one of the world's largest optical telescopes, at Siding Spring. In the early 1960s, the Australian and British governments proposed a partnership to build a joint optical telescope facility, and Gascoigne was among the experts involved. Former Mount Stromlo director and now head of the Greenwich observatory, Richard Woolley, was prominent in supporting the project from the British end. In 1967, the two governments formally agreed to collaborate on the construction of a large telescope, to be known as the Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 20 ...

(AAT). Given the existing infrastructure of the ANU's Siding Spring Observatory, the site was readily agreed as the location for the AAT. Gascoigne was one of the four members of the Technical Committee established to guide the telescope's development. He provided leadership on the design and optics of the new telescope, and was made the chief commissioning astronomer in 1974.

A bitter struggle over the management and operation of the new facility went on for some years. The Australian National University and the director at Stromlo, Olin Eggen, wanted the telescope to be under the control of the university while other Australian astronomers, including some at Stromlo, and the British wanted it established independently. Gascoigne's co-authored history of the telescope states that "None of the eight fellow of the Australian Academy of Science

The Fellowship of the Australian Academy of Science is made up of about 500 Australian scientists.

Scientists judged by their peers to have made an exceptional contribution to knowledge in their field may be elected to Fellowship of the Academy. ...

ascoigne was one of themsupported the ANU"Gascoigne ''et al.'', p. 139 and in 1973 the debate was resolved in favour of an independent structure, the Anglo-Australian Observatory

The Australian Astronomical Observatory (AAO), formerly the Anglo-Australian Observatory, was an optical and near-infrared astronomy observatory with its headquarters in North Ryde in suburban Sydney, Australia. Originally funded jointly by the U ...

. Gascoigne was one of only a few Stromlo employees who ended up working on the AAT for an extended period during its establishment phase:The head of the Mount Stromlo design section, mechanical engineer Herman Wehner, was full-time at the AAT during this period, working closely with Gascoigne. the Anglo-Australian Observatory chose to offer short-term positions rather than academic tenure

Tenure is a category of academic appointment existing in some countries. A tenured post is an indefinite academic appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency or program disco ...

like that at the ANU.

The work at Siding Spring was rewarding, but it could also be dangerous. During construction, Gascoigne constantly warned colleagues to take care on the elevated catwalks around the telescope. However, Gascoigne himself was almost killed when, while working one night around the telescope structure, he fell seven metres to the floor of the observatory, narrowly missing "a massive steel structure with long protruding bolts".The location inside the AAT dome is now known as "Gascoigne's Leap". He survived, and was the first to take a photograph using the telescope, on 26 or 27 April 1974. Gascoigne was so pleased with the quality of the optics that he said he wanted a number describing the hyperboloid

In geometry, a hyperboloid of revolution, sometimes called a circular hyperboloid, is the surface generated by rotating a hyperbola around one of its principal axes. A hyperboloid is the surface obtained from a hyperboloid of revolution by defo ...

shape of the mirror (1.1717) engraved on his headstone

A headstone, tombstone, or gravestone is a stele or marker, usually stone, that is placed over a grave. It is traditional for burials in the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim religions, among others. In most cases, it has the deceased's name, da ...

. The site quickly became one of the world's most important astronomical observatories and was for many years home to world-leading astrophotographer

Astrophotography, also known as astronomical imaging, is the photography or imaging of astronomical objects, celestial events, or areas of the night sky. The first photograph of an astronomical object (the Moon) was taken in 1840, but it was no ...

David Malin

David Frederick Malin (born 28 March 1941) is a British-Australian astronomer and photographer. He is principally known for his spectacular colour images of astronomical objects. A galaxy is named after him, Malin 1, which he discovered in ...

. The successes of the AAT have been documented in annual reports by its Board, while a 2008 analysis of the relative impacts of astronomical observing facilities placed the AAT in the top three, coming after only the Sloan Digital Sky Survey

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey or SDSS is a major multi-spectral imaging and spectroscopic redshift survey using a dedicated 2.5-m wide-angle optical telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, United States. The project began in 2000 a ...

and the W. M. Keck Observatory

The W. M. Keck Observatory is an astronomical observatory with two telescopes at an elevation of 4,145 meters (13,600 ft) near the summit of Mauna Kea in the U.S. state of Hawaii. Both telescopes have aperture primary mirrors, and when comp ...

(both telescopes built more than two decades later). For Gascoigne, it was "a wonderful thing to be associated with – the high point in my life."

It was during the period of Gascoigne's association with the Anglo-Australian telescope that he and his wife commissioned architect Theo Bischoff to design a house for them, which was planned and constructed between 1967 and 1969. Bischoff, who was responsible for numerous Canberra residences, designed a modernist home to the detailed, if contrasting, instructions from his client couple, who in turn were heavily influenced by their negative experiences with Canberra housing, particularly their home on Mount Stromlo. Based on Gascoigne's interest in optics, and Rosalie's strong visual sense as an artist, the resulting design "was based on maximising the potential for observation", creating "a form of habitable optical instrument".

Artist's assistant and historian

By the middle of 1975, the Anglo-Australian Telescope was fully operational, and Gascoigne was offered a job with the new telescope, based in Sydney. By this time his wife was emerging as a significant artist who relied on the landscapes and materials around their home for her inspiration. Gascoigne decided to return to the Australian National University in Canberra; he retired a few years later in 1980, and supported Rosalie in her work. Gascoigne completed a course in welding and became his wife's assistant, making "her assemblies of 'found objects' safer and more durable". He also catalogued and photographed her work, describing himself as "artist's handyman, cook, and archivist." Rosalie Gascoigne's artistic career came lateshe was almost 60 when she held her first solo shows – and her rise was "meteoric"; five public galleries purchased works from her early exhibitions. She died in 1999. In 2008, Gascoigne donated Rosalie's final major work, a ten-panel installation titled ''Earth'' (1999), to theNational Gallery of Australia

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA), formerly the Australian National Gallery, is the national art museum of Australia as well as one of the largest art museums in Australia, holding more than 166,000 works of art. Located in Canberra in th ...

.

As well as being an astronomer, Gascoigne was a scholar of the history of Australian astronomy. He wrote histories of major telescopes, such as the Melbourne Telescope and the AAT. He wrote biographies for the ''Australian Dictionary of Biography

The ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'' (ADB or AuDB) is a national co-operative enterprise founded and maintained by the Australian National University (ANU) to produce authoritative biographical articles on eminent people in Australia's ...

'', including those of the first trained astronomer at Canberra's Mount Stromlo Observatory, William Bolton Rimmer, and pioneering Australian astronomer Robert Ellery

Robert Lewis John Ellery (14 July 1827 – 14 January 1908) was an English-Australian astronomer and public servant who served as Victorian government astronomer for 42 years.

Early life

Ellery was born in Cranleigh, Surrey, England, the son of ...

.

Gascoigne died on 25 March 2010. A memorial service was held at St John's Church in Reid, Canberra, on 12 April.

Recognition and legacy

Gascoigne was widely respected for his astronomical skills and his generous nature. English astronomer and writerSir Fred Hoyle

Sir Fred Hoyle FRS (24 June 1915 – 20 August 2001) was an English astronomer who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and was one of the authors of the influential B2FH paper. He also held controversial stances on other sci ...

, at one time the Chairman of the AAT, gave Gascoigne considerable credit for the telescope's success, and astronomer Harry Minnett likewise credited him, together with Roderick Oliver Redman

Roderick Oliver Redman FRS (1905–1975) was Professor of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge.

Education

Redman was born at Rodborough near Stroud, Gloucestershire and educated at Marling School and St John's College, Cambridge.

Care ...

, for the telescope's extremely good optics. Former AAT director Russell Cannon regarded Gascoigne as a world leader in his field, as well as being "a delightful man". Historian of astronomy Ragbir Bhathal

Ragbir Bhathal was an Australian astronomer and author, based at the Western Sydney University (WSU), Australia. He was known for his work on Optical SETI, Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (OSETI). He continued lecturing and research a ...

considered Gascoigne to have been an important figure in Australian astronomy, responsible for substantial advances in the field.

In 1966, Gascoigne was elected a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science

The Australian Academy of Science was founded in 1954 by a group of distinguished Australians, including Australian Fellows of the Royal Society of London. The first president was Sir Mark Oliphant. The academy is modelled after the Royal Soci ...

. He was made an Honorary Fellow of the Astronomical Society of Australia; became the first person to be elected as an Honorary Member of the Optical Society of Australia; and was the first Australian to be elected as an Associate of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

.

On 11 June 1996, Gascoigne was made an Officer of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Gove ...

for his contributions to astronomy and to the AAT. On 1 January 2001, he was awarded the Centenary Medal

The Centenary Medal is an award which was created by the Australian Government in 2001. It was established to commemorate the centenary of the Federation of Australia and to recognise "people who made a contribution to Australian society or go ...

, for his service to society and to astronomy.

Select bibliography

;Scientific journal articles:These journal articles are Gascoigne's five most-cited works on theAstrophysics Data System

The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS) is an online database of over 16 million astronomy and physics papers from both peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed sources. Abstracts are available free online for almost all articles, and full scanned a ...

as of May 2010.

*

*

*

*

*

;Books

*

Footnotes

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Gascoigne, Ben 1915 births 2010 deaths 20th-century Australian astronomers 20th-century New Zealand astronomers New Zealand Protestants Officers of the Order of Australia People from Napier, New Zealand University of Auckland alumni Fellows of the Australian Academy of Science People educated at Auckland Grammar School New Zealand emigrants to Australia