Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (or BSRC, referred to locally in short as Restoration) is a

On July 16, 1964, an off-duty white police lieutenant, Thomas Gilligan, shot and killed a 15-year old black boy, James Powell. Two nights later, violence broke out in Harlem, and on July 20 rioting started at the intersection of Fulton Street and

On July 16, 1964, an off-duty white police lieutenant, Thomas Gilligan, shot and killed a 15-year old black boy, James Powell. Two nights later, violence broke out in Harlem, and on July 20 rioting started at the intersection of Fulton Street and

Late in 1965 Robert F. Kennedy, the junior senator of New York, decided to give an address on race and poverty. Disturbed by the Watts riots in

Late in 1965 Robert F. Kennedy, the junior senator of New York, decided to give an address on race and poverty. Disturbed by the Watts riots in

community development corporation

A community development corporation (CDC) is a not-for-profit organization incorporated to provide programs, offer services and engage in other activities that promote and support community development. CDCs usually serve a geographic location su ...

based in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and the first ever to be established in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

Background

Decline of Bedford–Stuyvesant

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the neighborhood of Bedford–Stuyvesant inBrooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, was home to middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

German, Dutch, Italian, Irish, and Jewish immigrants and their descendants. In the 1920s, African-Americans migrating from the South settled in the area. Starting in 1930, people from Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

moved into the neighborhood, seeking better housing. As the impoverished black population increased, banks reduced lending to local residents and businesses. By 1950, the number of blacks had risen to 155,000, comprising about 55 percent of the population of Bedford–Stuyvesant. Over the next decade, real estate agents

A real estate agent or real estate broker is a person who represents sellers or buyers of real estate or real property. While a broker may work independently, an agent usually works under a licensed broker to represent clients. Brokers and agen ...

and speculators employed blockbusting

Blockbusting was a business practice in the United States in which real estate agents and building developers convinced white residents in a particular area to sell their property at below-market prices. This was achieved by fearmongering the ho ...

to make quick profits. As a result, formerly middle-class white homes were turned over to poorer black families. By 1960, eighty-five percent of the population was black.

By the mid-1960s, 450,000 residents occupied the neighborhood's nine square miles. Bedford–Stuyvesant had become Brooklyn's most populous neighborhood and had the second largest concentration of African-Americans in the United States. Garbage pickup decreased and local schools deteriorated. The streets became dangerous as juvenile delinquency

Juvenile delinquency, also known as juvenile offending, is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as a minor or individual younger than the statutory age of majority. In the United States of America, a juvenile delinquent is a perso ...

, gang activity, and heroin

Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names, is a potent opioid mainly used as a recreational drug for its euphoric effects. Medical grade diamorphine is used as a pure hydrochloride salt. Various white and bro ...

use increased. Around 80 percent of residents were high school dropouts and about 36 percent of children were born to unmarried mothers. Economic downturn was in part facilitated by the decline of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

and the closure of a Sheffield Farms milk-bottling plant on Fulton Street. Almost half of the housing was officially classified as "dilapidated and insufficient." Rates of venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and ora ...

were among the highest in the United States, while infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of young children under the age of 1. This death toll is measured by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the probability of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births. The under-five morta ...

was the highest.

1964 riot and reaction

On July 16, 1964, an off-duty white police lieutenant, Thomas Gilligan, shot and killed a 15-year old black boy, James Powell. Two nights later, violence broke out in Harlem, and on July 20 rioting started at the intersection of Fulton Street and

On July 16, 1964, an off-duty white police lieutenant, Thomas Gilligan, shot and killed a 15-year old black boy, James Powell. Two nights later, violence broke out in Harlem, and on July 20 rioting started at the intersection of Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue

South end in Sheepshead Bay

Nostrand Avenue () is a major street in Brooklyn, New York, that runs for north from Emmons Avenue in Sheepshead Bay to Flushing Avenue in Williamsburg, where it continues as Lee Avenue. It occupies the position of ...

in Bedford–Stuyvesant. This carried on for three nights in the latter neighborhood and resulted in 276 arrests, 22 injuries, and 556 incidents of property damage which cost an estimated $350,000. The riot brought national attention to Bedford–Stuyvesant, but concern soon faded; after six months, the only improvement in the community was the paving of an empty lot.

On November 21, the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council hosted an all-day conference at Pratt Institute

Pratt Institute is a private university with its main campus in Brooklyn, New York. It has a satellite campus in Manhattan and an extension campus in Utica, New York at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. The school was founded in 1887 ...

in response to the summer riot. 600 local civic, religious, and political leaders discussed ways to improve the area. In the end it was decided that the Pratt Institute's Planning Department would conduct a six-month survey of local challenges and the potential for redevelopment. The study focused on a 12-block section of the community, finding much of the housing in the area at the point of decay. However, it was found that chances of rehabilitation in the area were "greatly enhanced" by the fact that 22.5 percent of buildings were owner occupied, 9.7 percent of buildings were owned by individuals that lived close by, and the average homeowner resided in the area for 15 years. The Planning Department's report concluded that New York City should "mobilize all necessary antipoverty and other social welfare and educational programs" to save the neighborhood from further decline. However, Youth-in-Action, the community's city anti-poverty agency, was only allocated $440,000 out of a requested $2.6 million budget for 1965, forcing it to cut many of its programs.

Robert F. Kennedy's involvement

Late in 1965 Robert F. Kennedy, the junior senator of New York, decided to give an address on race and poverty. Disturbed by the Watts riots in

Late in 1965 Robert F. Kennedy, the junior senator of New York, decided to give an address on race and poverty. Disturbed by the Watts riots in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, he was worried that America's racial crisis was shifting from the rural South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

to the urban North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

. He was also concerned that white support for black demands within the community was declining and that race relations were near to boiling over.

Kennedy gave three consecutive speeches in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

on January 20, 21, and 22, 1966. Most of the content was in line with John F. Kennedy's New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as the ...

programs, with proposals for job training, rent subsidies, students loans for the poor, and housing desegregation. He also broke with President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

rhetorical optimism, arguing that the situation for black Americans was worsening instead of improving. He asserted that welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

and stricter code enforcement were not solving the problems facing ghettos and that community involvement and action from the private sector were necessary to effectively combat urban poverty. Kennedy warned that failure to act could lead to more race riots. Several days later, Kennedy decided to create his own anti-poverty program. He told speechwriter Adam Walinsky

Adam Walinsky (born 1937) is a lawyer who served in the United States Department of Justice and as a speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy. He had also been the 1970 nominee for New York Attorney General by the Democratic Party. He criticized Ira ...

, "I want to do something about all this. Some kind of project that goes after some of these problems ..ee what you can put together."

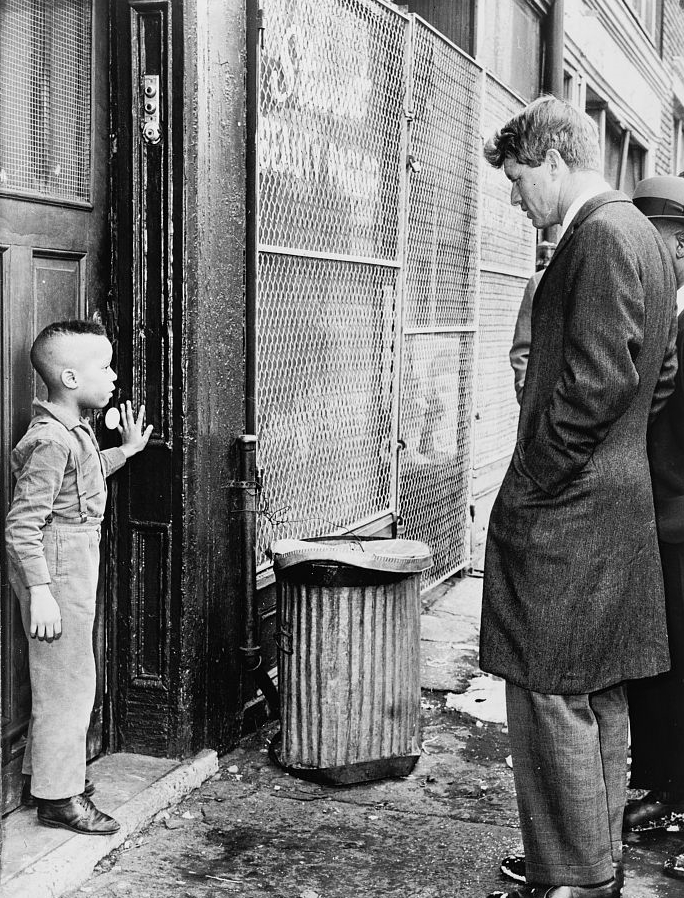

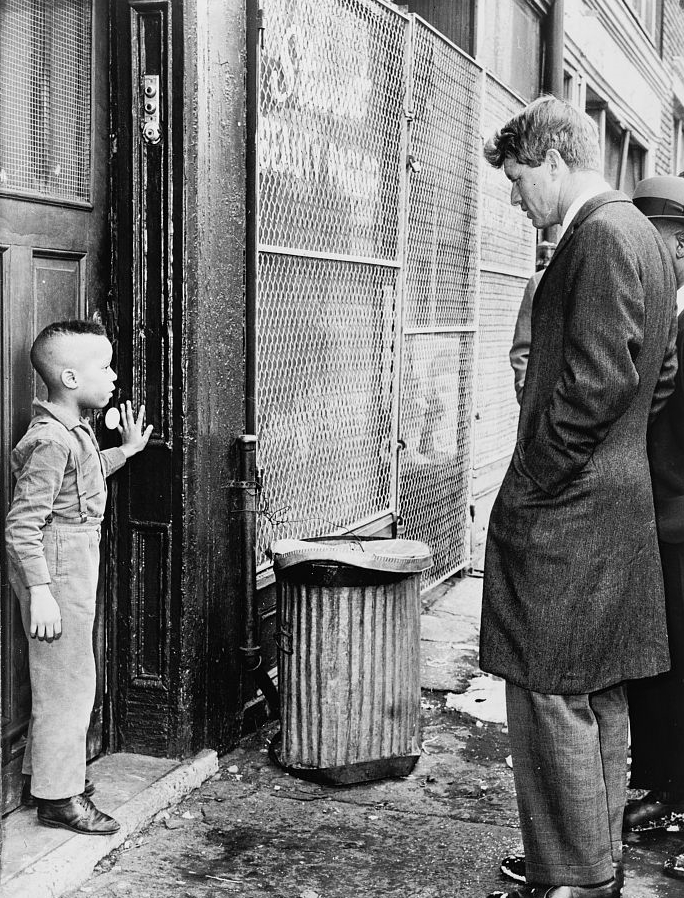

In mid-February, Kennedy spent an afternoon touring Bedford–Stuyvesant. Afterwards, he attended a meeting with community activists at the local YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

building. Similar in manner to the Baldwin–Kennedy meeting

The Baldwin–Kennedy meeting of May 24, 1963 was an attempt to improve race relations in the United States. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy invited novelist James Baldwin, along with a large group of cultural leaders, to meet in a Kennedy a ...

of 1964, Brooklyn community leaders were bitter towards the senator and lectured him on the problems black residents of the neighborhood faced. Civil Court Judge Thomas R. Jones said, "I'm weary of study, Senator. Weary of speeches, weary of promises that aren't kept ..he Negro people are angry, Senator, and, judge that I am, I'm angry, too. No one is helping us." Kennedy was irritated by the way he was treated. As he drove back to Manhattan he told his aides, "I could be smoking a cigar down in Palm Beach. I don't really have to take that. Why do I have to go out and get abused for a lot of things I haven't done?" Several moments later he said, "Maybe this would be a good place to try and make an effort."

History

Planning and design

Throughout the summer of 1966 Senator Kennedy's aides, Walinsky and Thomas Johnston, planned an anti-poverty program. As part of their research, they traveled across the country to consult black militants, urban theorists, federal administrators, journalists, mayors, foundation leaders, and banking and business executives. Johnston spent much of his time in Bedford–Stuyvesant trying to sort out differences between the community's middle-class leadership.Earl G. Graves, Sr.

Earl Gilbert Graves Sr. (January 9, 1935 – April 6, 2020) was an American entrepreneur, publisher, businessman, philanthropist, and advocate of African-American businesses. A graduate of Morgan State University, he was the founder of ''Bla ...

, a former real-estate broker from the area, was brought in to assist him. Realizing that the Johnson administration and Brooklyn's white Democrats felt politically threatened by his project, Kennedy secured support from

Mayor John Lindsay

John Vliet Lindsay (; November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician and lawyer. During his political career, Lindsay was a U.S. congressman, mayor of New York City, and candidate for U.S. president. He was also a regular ...

and the senior senator from New York, Jacob Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician. During his time in politics, he represented the state of New York in both houses of the United States Congress. A member of the Republican Party, he al ...

, both Republicans. He also earned corporate support from Thomas Watson Jr.

Thomas John Watson Jr. (January 14, 1914 – December 31, 1993) was an American businessman, political figure, Army Air Forces pilot, and philanthropist. The son of IBM Corporation founder Thomas J. Watson, he was the second IBM president (195 ...

of IBM, William S. Paley of CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

, investment banker André Meyer

André Benoît Mathieu Meyer (September 3, 1898 – September 9, 1979) was a French-American investment banker.

Biography

Meyer was born to a low-income Jewish family in Paris. As a boy, he began following the workings of the stock market and ...

, and former Secretary of Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

C. Douglas Dillon. Only David Rockefeller

David Rockefeller (June 12, 1915 – March 20, 2017) was an American investment banker who served as chairman and chief executive of Chase Manhattan Corporation. He was the oldest living member of the third generation of the Rockefeller family, ...

declined to support the project.

By October, Kennedy, his staff, and community leaders had resolved to launch a community development corporation

A community development corporation (CDC) is a not-for-profit organization incorporated to provide programs, offer services and engage in other activities that promote and support community development. CDCs usually serve a geographic location su ...

for the near-entirety of the ghetto of Bedford–Stuyvesant. Kennedy later said, "An effort in one problem area is almost worthless. A program for housing, without simultaneous programs for jobs, education, welfare reform, health, and economic development cannot succeed. The whole community must be involved as a whole." Initial plans included coordinated programs for the creation of jobs, housing renovation and rehabilitation, improved health sanitation, and recreation facilities, the construction of two "super blocks," the conversion of the abandoned Sheffield Farms milk-bottling plant into a town hall and community center, a mortgage consortium to provide subsidized loans for homeowners, the founding of a private work-study community college for dropouts, and a public campaign to convince corporations to invest in industry in the neighborhood.

A few days before the project was going to publicly unveiled, Kennedy said "I'm not at all sure this is going to work. But it's going to test some new ideas, some new ways of doing this, that are different from the government's. Even if we fail, we'll have learned something. But more important than that, something has to be done. People like myself can't go around making nice speeches all the time. We can't just keep raising expectations. We have to do some damn hard work, too."

First founding

On December 9, 1966, Kennedy, together with Mayor Lindsay and Senator Javits, announced his anti-poverty program at New York Public School 305. He told the audience, "The program for the development of Bedford–Stuyvesant will combine the best of community action with the best of the private enterprise system. Neither by itself is enough, but in their combination lies our hope for the future." The plan was met with mixed reactions in the press, with some liberals accusing the project of relying too heavily on the private sector while conservative elements were more hopeful of its chances for success. Initially, the responsibility of the revival of the neighborhood rested with two private, nonprofit corporations. The first, Bedford–Stuyvesant Renewal and Rehabilitation Corporation (R & R), consisted of 20 established civic and religious community leaders under the leadership of Judge Thomas R. Jones. Its purpose was to design anti-poverty programs and retain basic decision-making authority. The second, Distribution and Services (D & R) was to secure financial and logistical support for the former. It was run by an all-white board of businessmen that included Watson, Paley, Meyer, Dillon,David Lilienthal

David Eli Lilienthal (July 8, 1899 – January 15, 1981) was an American attorney and public administrator, best known for his Presidential Appointment to head Tennessee Valley Authority and later the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He had p ...

and Jacob Merrill Kaplan. Roswell Gilpatric, James Oates

James Oates (died 1751) was a British stage actor.

Possibly of Irish birth, he was a long-standing member of the Drury Lane company from 1718, and also appeared at the summer fairs in London including Southwark and Bartholomew Fair. He speciali ...

, and Benno C. Schmidt Sr. were later added.

Internal disputes and second founding

The community corporation's membership was almost entirely middle class and about one-third female. Many factions in Bedford–Stuyvesant felt underrepresented, resulting in bitter political infighting. In March 1967 Judge Jones reached an impasse with the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council. With the support of Kennedy and Lindsay, he demanded that the R & R board resolve to expand itself to include a wider array of community leaders and give him three weeks to revise the corporation's structure. The ultimatum lost by a single vote and Jones angrily resigned. The ensuing dispute threatened to derail the entire project. Kennedy tried to salvage it by dissolving the R & R and creating a new restoration corporation. Arguing that a more representative group was needed to secure federal and private grants, he won the support of Lindsay and Javits to proceed. On April 1, Jones announced the formation of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (BSRC). It was the firstcommunity development corporation

A community development corporation (CDC) is a not-for-profit organization incorporated to provide programs, offer services and engage in other activities that promote and support community development. CDCs usually serve a geographic location su ...

in the United States. The new board included Sonny Carson, Albert Vann

Albert Vann (November 19, 1934 – July 14, 2022) was an American politician and a member of the New York City Council from Brooklyn, representing the 36th district, which includes parts of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights. He was a Dem ...

, and Milton Galamison

Milton Arthur Galamison (March 25, 1923 – March 9, 1988) was a Presbyterian minister who served in Brooklyn, New York.

As a community activist, he championed integration and education reform in the New York City public school system, and org ...

. Franklin A. Thomas

Franklin Augustine Thomas (May 27, 1934 – December 22, 2021) was an American businessman and philanthropist who was president and CEO of the Ford Foundation from 1979 until 1996. After leaving the foundation, Thomas continued to serve in leade ...

selected to be the first President and CEO of the new corporation.

Initial activities

The corporations received their first grants from the Stern Family Fund, J. M. Kaplan Fund,Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

and Astor Foundation. Seven months later they received a $7 million grant from the Department of Labor made possible by a 1966 amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 () authorized the formation of local Community Action Agencies as part of the War on Poverty. These agencies are directly regulated by the federal government. "It is the purpose of The Economic Opportunity Ac ...

drafted by Kennedy and Javits to provide the private sector with incentive payments in exchange for investments in impoverished areas. In spite of a public awareness campaign and support from several prominent Republicans, the project only received modest support from private businesses. Investments from IBM, Xerox

Xerox Holdings Corporation (; also known simply as Xerox) is an American corporation that sells print and digital document products and services in more than 160 countries. Xerox is headquartered in Norwalk, Connecticut (having moved from St ...

, and U.S. Gypsum

USG Corporation, also known as United States Gypsum Corporation, is an American company which manufactures construction materials, most notably drywall and joint compound. The company is the largest distributor of wallboard in the United States ...

notwithstanding, most corporate executives believed there was little profit in poorer communities and were concerned about hostile working environments. Most of the residents of Bedford–Stuyvesant were initially skeptical of the project's intentions.

Planning occurred throughout the early months of 1967. By March, a strategy had been laid out for the physical reconstruction and rehabilitation of Bedford–Stuyvesant. It centered around a two-block-wide commercial zone to be located between Fulton Street and Atlantic Avenue which would serve as a principal point for local business and community organizations. Several lightly trafficked roads were chosen to be transformed into landscaped walkways. Architect I. M. Pei was commissioned for the establishment of the two "superblocks". Local residents believed the proposal was purely cosmetic and insisted that housing and employment programs be given greater attention. Pei was eventually able to convince more of the more corporation staff to support his plan.

Meanwhile, members of the still-functional D & S board were working on areas of their expertise; Paley began exploring the development of communications infrastructure, George S. Moore focused on project financing and mortgage pooling, Schmidt assisted small businesses, Watson managed job training and employment programs, and Meyer worked on real estate problems and strategized for the corporation's overall funding. Wanting to earn the trust of the community, Thomas organized the "Community Home Improvement Program" (CHIP). With labor drawn from unemployed youth, various houses would be chosen by lottery to have their exteriors refurbished. In turn, homeowners would provide a token payment of $25 (for work valued at $325). The corporation would continue to maintain the houses after rehabilitation. Though seen by Judge Jones as "superficial", the program went into effect with a $500,000 federal grant and quickly became popular. The D & S board gradually began to lose its supremacy over the BSRC. Thomas lobbied for an end of D & S control over funding and created a joint account to be managed by both corporations. In December 1967 Kennedy brought in John Doar

John Michael Doar (December 3, 1921 – November 11, 2014) was an American lawyer and senior counsel with the law firm Doar Rieck Kaley & Mack in New York City. During the administrations of presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he ...

to be the new executive director of the D & S board. One of his first actions was to relocate the businessmen corporation's staff into the BSRC's offices. It was seen by community leaders as a hindrance and eventually dissolved.

The BSRC also produced a television series about the neighborhood, ''Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant'', which premiered in April 1968. By December, the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation had restored 400 brownstone

Brownstone is a brown Triassic–Jurassic sandstone that was historically a popular building material. The term is also used in the United States and Canada to refer to a townhouse clad in this or any other aesthetically similar material.

Type ...

s and tenements with the help of 272 local residents, 250 of whom were later hired in full-time construction jobs. Two "Neighborhood Restoration Centers" for free advice and legal consultation had been opened, 14 new black-owned businesses had been established, and 1,200 residents had received vocational

A vocation () is an occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. People can be given information about a new occupation through student orientation. Though now often used in non-religious c ...

training. IBM located a computer cable plant in the neighborhood, creating 300 new jobs, while the City University of New York

The City University of New York ( CUNY; , ) is the public university system of New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven senior colleges, seven community colleges and seven pro ...

had agreed to coordinate with community leaders for the construction of a new community college in the area. A mortgage pool fund run by a consortium of 65 banks loaned $1.5 million to homeowners. Still, progress was slow and journalist Jack Newfield

Jack Abraham Newfield (February 18, 1938 – December 21, 2004) was an American journalist, columnist, author, documentary filmmaker and activist. Newfield wrote for the ''Village Voice'', ''New York Daily News'', ''New York Post'', ''New Y ...

estimated that of Bedford–Stuyvesant's 450,000 inhabitants, only about 25,000 had been affected by the corporation's work.

In 1968 the BSRC purchased the abandoned milk-bottling plant on Fulton street for rehabilitation. Its restoration was completed in 1972 and it became the new corporate headquarters for the BSRC, entitled Restoration Plaza. In 1979, Pathmark

Pathmark is a supermarket brand owned by Allegiance Retail Services, a retailers’ cooperative based in Iselin, New Jersey, USA. Pathmark currently has one location in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York, which it has operated since 2019.

From ...

opened the first supermarket in Bedford-Stuyvesant in the plaza.

In 1971, the BSRC looked to stimulate the region's economy through employment, education, and healthcare programming. This included a textile project by the Design Works of Bedford-Stuyvesant, founded by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, shown at a gala event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

21st century

As of 2010, Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation had constructed or rehabilitated 2200 housing units in the neighborhood, provided mortgage financing to nearly 1500 homeowners, brought $375 million in investments to the community, and created over 20,000 jobs. Restoration Plaza currently serves as an office and mall complex for the surrounding area and as the unofficial downtown of Bedford–Stuyvesant. In addition to housing utilities services and a post office, the building hosts the BSRC's Center for Arts and Culture. This includes the Billie Holiday Theatre, Restoration Dance Theater, and the Skylight Art Gallery. The Youth Arts Academy, Under One Sun, and Phat Tuesday programs are also run from the plaza.Citations

References

* * * * * {{Authority control 1967 establishments in New York City Organizations established in 1967 Community development organizations Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Robert F. Kennedy 501(c)(3) organizations Non-profit organizations based in Brooklyn