Battle of Ollantaytambo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Ollantaytambo ( es, Batalla de Ollantaytambo, ) took place in January 1537, between the forces of Inca emperor

In 1531, a group of Spaniards led by

In 1531, a group of Spaniards led by

Manco Inca had gathered more than 30,000 troops at Ollantaytambo, among them, a large number of recruits from tribes of the

Manco Inca had gathered more than 30,000 troops at Ollantaytambo, among them, a large number of recruits from tribes of the

The actual location of the battle is the subject of some controversy. According to Canadian explorer

The actual location of the battle is the subject of some controversy. According to Canadian explorer

Manco Inca

Manco Inca Yupanqui ( 1515 – c. 1544) (''Manqu Inka Yupanki'' in Quechua) was the founder and monarch (Sapa Inca) of the independent Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba, although he was originally a puppet Inca Emperor installed by the Spaniards. ...

and a Spanish expedition led by Hernando Pizarro during the Spanish conquest of Peru

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish s ...

. A former ally of the Spaniards, Manco Inca rebelled in May 1536, and besieged a Spanish garrison in the city of Cusco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

. To end the stand-off, the besieged mounted a raid against the emperor's headquarters in the town of Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo ( qu, Ullantaytampu) is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamb ...

. The expedition, commanded by Hernando Pizarro, included 100 Spaniards and some 30,000 Indian auxiliaries

Indian auxiliaries were those indigenous peoples of the Americas who allied with Spain and fought alongside the conquistadors during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. These auxiliaries acted as guides, translators and porters, and in the ...

against an Inca army more than 30,000 strong.

There is some controversy over the actual location of the battle; according to some, it took place in the town itself, while Jean-Pierre Protzen and John Hemming John Hemming may refer to:

* John Hemming (historian) (born 1935), British explorer and author

*John Hemming (politician) (born 1960), British politician

See also

*John Heminges, co-publisher of Shakespeare's works after his death

*John Hemings

J ...

argue that the nearby plain of Mascabamba better matches the descriptions of the encounter. In any case, the Inca army managed to hold the Spanish forces from a set of high terraces and flood their position to hinder their cavalry. Severely pressed and unable to advance, the Spaniards withdrew by night to Cusco. Despite this victory, the arrival of Spanish reinforcements to Cusco forced Manco Inca to abandon Ollantaytambo and seek refuge in the heavily forested region of Vilcabamba, where he established the small independent Neo-Inca State

The Neo-Inca State, also known as the Neo-Inca state of Vilcabamba, was the Inca state established in 1537 at Vilcabamba by Manco Inca Yupanqui (the son of Inca emperor Huayna Capac). It is considered a rump state of the Inca Empire (1438–15 ...

which survived until 1572.

Prelude

In 1531, a group of Spaniards led by

In 1531, a group of Spaniards led by Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

landed on the shores of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

, thus starting the Spanish conquest of Peru

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish s ...

. At that time the empire was emerging from a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in which Atahualpa

Atahualpa (), also Atawallpa ( Quechua), Atabalica, Atahuallpa, Atabalipa (c. 1502 – 26-29 July 1533) was the last Inca Emperor. After defeating his brother, Atahualpa became very briefly the last Sapa Inca (sovereign emperor) of the Inca Em ...

had defeated his brother Huascar to claim the title of Sapa Inca

The Sapa Inca (from Quechua ''Sapa Inka'' "the only Inca") was the monarch of the Inca Empire (''Tawantinsuyu''), as well as ruler of the earlier Kingdom of Cusco and the later Neo-Inca State. While the origins of the position are mythical and ...

. Atahualpa underestimated the strength of the small force of Spaniards and was captured during an ambush at Cajamarca in November 1532. Pizarro ordered the execution of the emperor in July 1533, and occupied the Inca capital of Cusco four months later. To replace Atahualpa, Pizarro installed his brother Túpac Huallpa

Túpac Huallpa (or Huallpa Túpac) (1510 – October 1533), original name Auqui Huallpa Túpac, was the first vassal Sapa Inca installed by the Spanish conquistadors, during the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire led by Francisco Pizarro.

Life ...

as a puppet ruler, but he died shortly afterwards. Another brother, Manco Inca

Manco Inca Yupanqui ( 1515 – c. 1544) (''Manqu Inka Yupanki'' in Quechua) was the founder and monarch (Sapa Inca) of the independent Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba, although he was originally a puppet Inca Emperor installed by the Spaniards. ...

, was crowned in his place. During this stage, Atahualpa's generals were the only opposition to the Spanish advance as a sizable part of the empire's population had fought on Huascar's side during the civil war and joined Pizarro against their enemies.

For a while, Manco Inca and the conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

s maintained cordial relations, together they defeated Atahualpa's generals and reestablished Inca rule over most of the empire. However, Manco came to realize that real authority rested in Spanish hands when his house was looted with impunity by a Spaniard mob in 1535. Following this episode, the Inca emperor was subject to constant harassment as the Spaniards demanded gold, took away his wives, and even imprisoned him. In response, he fled his capital to start an uprising. In May 1536, an Inca army besieged Cusco, which was garrisoned by a group of Spaniards and native allies. The conquistadors were hard pressed but they managed to resist and counterattack, storming the main Inca stronghold at Sacsayhuaman. Meanwhile, Manco's generals occupied the central highlands of Peru and annihilated several expeditions sent to reinforce Cusco but failed in their attempt to take the recently founded Spanish capital of Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

. As a result of these events, neither side was able to break the deadlock at Cusco for several months, so the Spaniard garrison decided to make a direct attack on Manco's headquarters at the town of Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo ( qu, Ullantaytampu) is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamb ...

, northwest of the city.

Sources

Primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was created at the time under ...

s about the battle of Ollantaytambo were written mainly by Spaniards. Pedro Pizarro

Pedro Pizarro (c. 1515 – c. 1602) was a Spanish chronicler and conquistador. He took part in most events of the Spanish conquest of Peru and wrote an extensive chronicle of them under the title ''Relación del descubrimiento y conquista de ...

, a cousin of Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

, was part of the expedition against Manco Inca's headquarters. Years later he wrote down his recollections of these and other events in a chronicle called ''Relación del descubrimiento y conquista de los reinos del Perú'', completed in 1571. The anonymous ''Relación del sitio del Cuzco y principio de las guerras civiles del Perú hasta la muerte de Diego de Almagro'' starts in January 1536 when Hernando Pizarro arrived in Cusco, and ends with the execution of Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro (; – July 8, 1538), also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo, was a Spanish conquistador known for his exploits in western South America. He participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest of Peru. While subd ...

in July 1538. This chronicle, which includes an account of Manco Inca's rebellion and the attack on Ollantaytambo, was written in 1539 probably by Diego de Silva, a Spanish soldier who was actually in Lima during the uprising. An account of the battle was also included in the ''Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las islas y tierra firme del Mar Oceano'' written by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas

Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549 – 28 March 1626 or 27 March 1625) was a chronicler, historian, and writer of the Spanish Golden Age, author of ''Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del mar ...

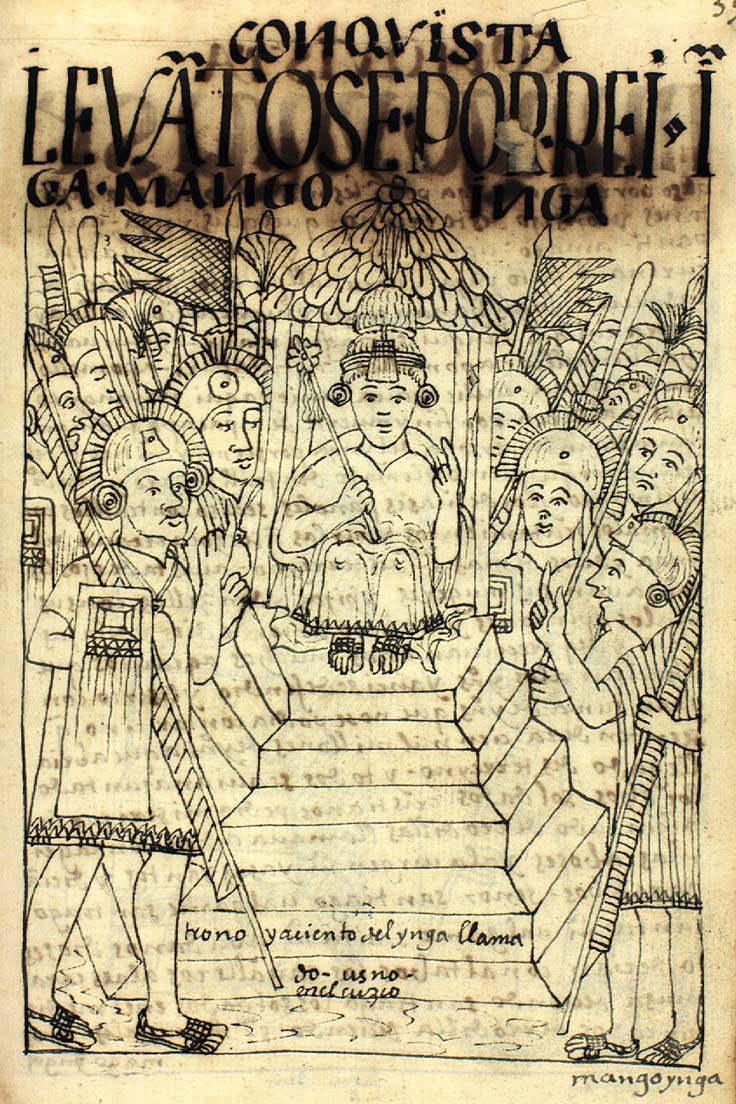

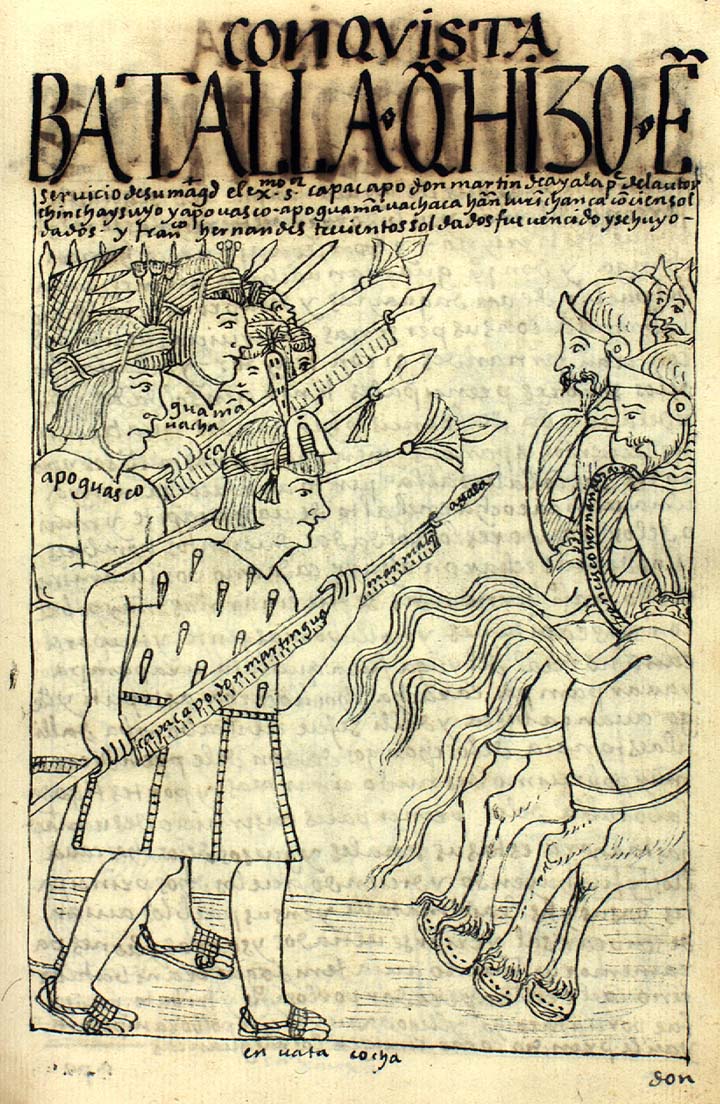

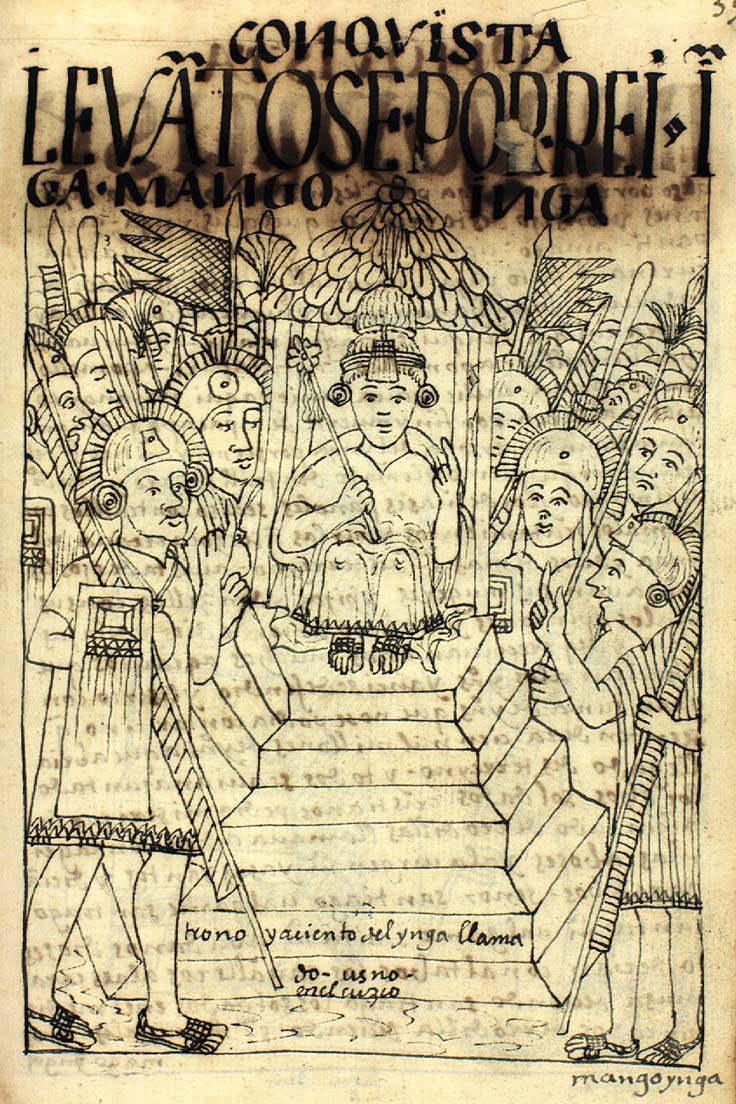

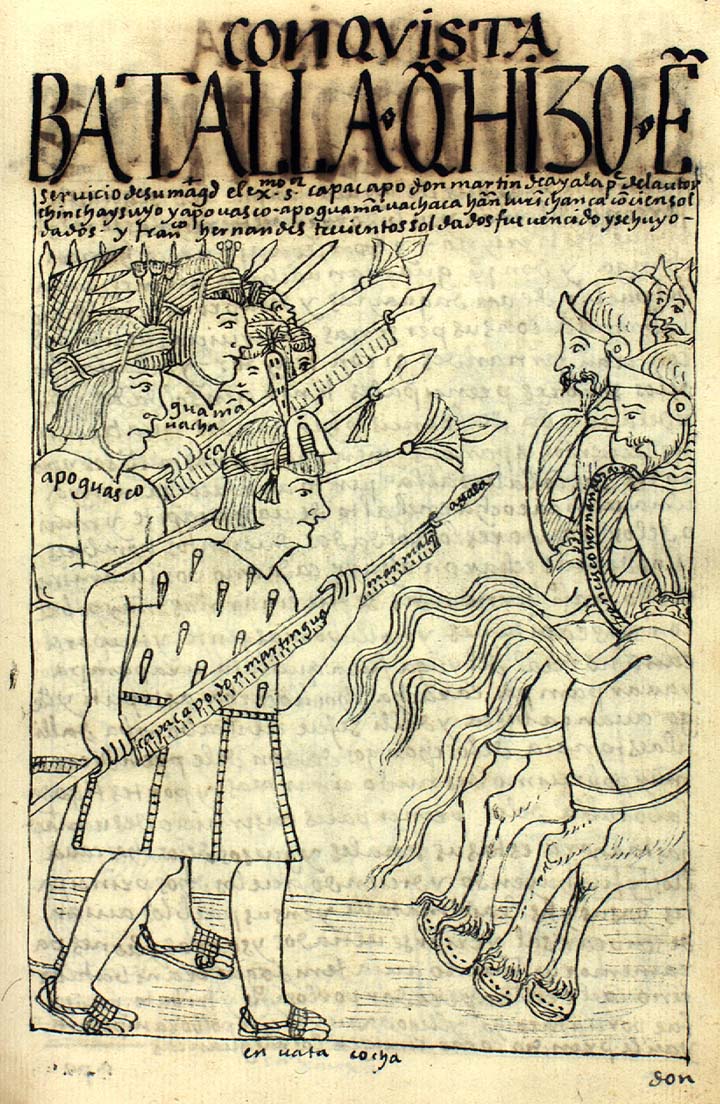

between 1610 and 1615. Herrera was the ''Cronista Mayor de las Indias'' (Chronicler-in-Chief of the Indies) of the Spanish Crown and despite writing in Madrid, had access to many documents and sources. On the Inca side, the only written account of the battle is included in the ''Relación de la conquista del Perú y hechos del Inca Manco II'' written in 1570 by Titu Cusi Yupanqui

''Don'' Diego de Castro Titu Cusi Yupanqui (; Quechua: ''Titu Kusi Yupanki'' ; 1529–1571) was an Inca ruler of Vilcabamba and the penultimate leader of the Neo-Inca State. He was a son of Manco Inca Yupanqui, He was crowned in 1563, after t ...

, son of Manco Inca.

Order of battle

Manco Inca had gathered more than 30,000 troops at Ollantaytambo, among them, a large number of recruits from tribes of the

Manco Inca had gathered more than 30,000 troops at Ollantaytambo, among them, a large number of recruits from tribes of the Amazon Rainforest

The Amazon rainforest, Amazon jungle or ; es, Selva amazónica, , or usually ; french: Forêt amazonienne; nl, Amazoneregenwoud. In English, the names are sometimes capitalized further, as Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Forest, or Amazon Jungle. ...

. Manco Inca's forces were a militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

army made up mostly of conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

farmers with only rudimentary weapons training.Hemming, ''The conquest'', p. 207. This was the regular fare in the Inca Empire, where military service was a duty for all married men between 25 and 50 years old. In combat, these soldiers were organized according to their ethnic group and led into battle by their native leaders, called ''kuraka

A ''kuraka'' (Quechua for the principal governor of a province or a communal authority in the Tawantinsuyu), or curaca (hispanicized spelling), was an official of the Inca Empire who held the role of magistrate, about four levels down from the Sa ...

s''. They used melee weapon

A melee weapon, hand weapon or close combat weapon is any handheld weapon used in hand-to-hand combat, i.e. for use within the direct physical reach of the weapon itself, essentially functioning as an additional (and more impactful) extension of th ...

s such as maces, clubs, and spears, as well as ranged weapon

A ranged weapon is any weapon that can engage targets beyond hand-to-hand distance, i.e. at distances greater than the physical reach of the user holding the weapon itself. The act of using such a weapon is also known as shooting. It is someti ...

s such as arrows, javelins, and slings; protective gear included helmets, shields, and quilted cloth armor. Against the conquistadors, wooden clubs and maces with stone or bronze heads were rarely able to penetrate Spanish armor; slings and other missile throwing weapons were somewhat more effective due to their accuracy and the large size of their projectiles. Even so, Inca soldiers were no match for the Spanish cavalry in open terrain so they resorted to fighting on rough terrain and digging pits in open fields to hinder the mobility of horses.

The attack was led by Hernando Pizarro, the senior Spanish commander in Cusco, with a force of 100 Spaniards (30 infantry, 70 cavalry) and an estimated 30,000 native allies. One of his main assets against the Inca armies was the Spanish cavalry because horses provided a considerable advantage in hitting power, maneuverability, speed, and stamina over Inca warriors. All Spaniards wore some kind of armor, the most commonly used types were chain mail

Chain mail (properly called mail or maille but usually called chain mail or chainmail) is a type of armour consisting of small metal rings linked together in a pattern to form a mesh. It was in common military use between the 3rd century BC and ...

shirts and padded cloth armor which were lighter and cheaper than full armor suits; they were complemented by steel helmets and small iron or wooden shields. The main Spanish offensive weapon was the steel sword, which horsemen supplemented with the lance; both weapons could easily penetrate the padded armor worn by Inca troops. Firearms, such as arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es were rarely used during the Spanish conquest of Peru because they were scarce, hard to use, and despised by horsemen as an ungentlemanly weapon. Spaniards relied heavily on Indian auxiliaries

Indian auxiliaries were those indigenous peoples of the Americas who allied with Spain and fought alongside the conquistadors during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. These auxiliaries acted as guides, translators and porters, and in the ...

because they provided thousands of warriors as well as support personnel and supplies.D'Altroy, ''The Incas'', p. 319. These native troops had the same sorts of arms and armor as their Inca counterparts. During the Ollantaytambo campaign, the Pizarro expedition included thousands of auxiliaries, mainly Cañari

The Cañari (in Kichwa: Kañari) are an indigenous ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the territory of the modern provinces of Azuay and Cañar in Ecuador. They are descended from the independent pre-Columbian tribal confederation of the ...

s, Chachapoyas, and Wankas, as well as several members of the Inca nobility opposed to Manco Inca.

Battle

The main access route to Ollantaytambo runs along a narrow valley formed in the mountains by theUrubamba River

The Urubamba River or Vilcamayo River (possibly from Quechua ''Willkamayu'', for "sacred river") is a river in Peru. Upstream it is called Vilcanota River (possibly from Aymara ''Willkanuta'', for "house of the sun"). Within the La Convención ...

, which connects the site with Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu is a 15th-century Inca citadel located in the Eastern Cordillera of southern Peru on a mountain range.UNESCO World Heritage Centre. It is located in the Machupicchu District within Urubamba Province above the Sacred Valley, whic ...

to the west and with Pisaq and Cusco to the east. After his uprising, Manco Inca fortified the eastern approaches to fend off attacks from the former Inca capital, now under Spanish occupation. The first line of defense was a steep bank of terraces at Pachar, near the confluence of the Anta and Urubamba rivers. Behind it, the Incas channeled the Urubamba to make it cross the valley from right to left and back thus forming two more lines backed by the fortifications of Choqana on the left bank and 'Inkapintay on the right bank. Past them, at the plain of Mascabamba, eleven high terraces closed the valley between the mountains and a deep canyon formed by the Urubamba. The only way to continue was through the gate of T'iyupunku, a thick defensive wall with two narrow doorways. In the event of these fortifications being overrun, the Temple Hill, a religious center surrounded by high terraces overlooking Ollantaytambo, provided a last line of defense.

Faced with these constraints, the Spanish expedition had to cross the river several times and fight at each ford against stiff opposition. The bulk of the Inca army confronted the Spaniards from a set of terraces overlooking a plain by the Urubamba River. Several Spanish assaults against the terraces failed against a shower of arrows, slingshots, and boulders coming down from the terraces as well as from both flanks. To hinder the efforts of the Spanish cavalry, the Incas flooded the plain using previously prepared channels; water eventually reached the horses' girths. The defenders then counterattacked; some of them used Spanish weapons captured in previous encounters such as swords, buckler

A buckler (French ''bouclier'' 'shield', from Old French ''bocle, boucle'' 'boss') is a small shield, up to 45 cm (up to 18 in) in diameter, gripped in the fist with a central handle behind the boss. While being used in Europe since ant ...

s, armor, and even a horse, ridden by Manco Inca himself. In a severely compromised situation, Hernando Pizarro ordered a retreat; under the cover of darkness the Spanish force fled through the Urubamba valley with the Incas in pursuit and reached Cusco the next day.

Battle site

The actual location of the battle is the subject of some controversy. According to Canadian explorer

The actual location of the battle is the subject of some controversy. According to Canadian explorer John Hemming John Hemming may refer to:

* John Hemming (historian) (born 1935), British explorer and author

*John Hemming (politician) (born 1960), British politician

See also

*John Heminges, co-publisher of Shakespeare's works after his death

*John Hemings

J ...

, Spanish forces occupied a plain between Ollantaytambo and the Urubamba River while the main Inca army was located on a citadel (the Temple Hill) overlooking the town, protected by seventeen terraces. However, Swiss architect Jean-Pierre Protzen argues that the topography of the town and its surrounding area does not match contemporary descriptions of the battle. An anonymous account attributed to Diego de Silva claims that the Inca army occupied a set of eleven terraces, not seventeen; while the chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and ...

of Pedro Pizarro

Pedro Pizarro (c. 1515 – c. 1602) was a Spanish chronicler and conquistador. He took part in most events of the Spanish conquest of Peru and wrote an extensive chronicle of them under the title ''Relación del descubrimiento y conquista de ...

describes a gate flanked by walls as the only way through the terraces. Protzen thinks that these descriptions allude to a set of eleven terraces that close the plain of Mascabamba, near Ollantaytambo, which include the heavily fortified gate of T'iyupunku. At this location, when the Spaniards faced the terraces they would have had the Urubamba River to their left and the steep hill of Cerro Pinkuylluna to their right, matching the three sides from which they were attacked during the battle. If Protzen's hypothesis is correct, the river diverted to flood the battlefield was the Urubamba, and not its smaller affluent, the Patakancha, which runs alongside the town of Ollantaytambo.

Aftermath

The success at Ollantaytambo encouraged Manco Inca to make a renewed attempt against Cusco. However, the Spaniards discovered the Inca army concentrating near the city and mounted a night attack, which inflicted heavy casualties. On April 18, 1537, a Spanish army led byDiego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro (; – July 8, 1538), also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo, was a Spanish conquistador known for his exploits in western South America. He participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest of Peru. While subd ...

returned from a long expedition to Chile and occupied Cusco. Almagro imprisoned Hernando Pizarro and his brother Gonzalo because he wanted the city for himself; most Spanish troops and their auxiliaries joined his side. He had previously tried to negotiate a settlement with Manco Inca but his efforts failed when both armies clashed at Calca, near Cusco. With the Spaniards' position consolidated by Almagro's reinforcements, Manco Inca decided that Ollantaytambo was too close to Cusco to be tenable so he withdrew further west to the town of Vitcos. Almagro sent his lieutenant Rodrigo Orgóñez Rodrigo Orgóñez (1490 – 26 April 1538) was Spanish captain under Diego de Almagro.

Born in Oropesa, Rodrigo participated in the Italian Campaigns. He accompanied Francisco de Godoy from Nicaragua when they joined Diego's men in reinforci ...

in pursuit with 300 Spaniards and numerous Indian auxiliaries. In July 1537, Orgoñez occupied and sacked Vitcos taking many prisoners, but Manco managed to escape. He took refuge at Vilcabamba, a remote location where the Neo-Inca State

The Neo-Inca State, also known as the Neo-Inca state of Vilcabamba, was the Inca state established in 1537 at Vilcabamba by Manco Inca Yupanqui (the son of Inca emperor Huayna Capac). It is considered a rump state of the Inca Empire (1438–15 ...

was established and lasted until the capture and execution of Túpac Amaru

Túpac Amaru (1545 – 24 September 1572) (first name also spelled Tupac, Topa, Tupaq, Thupaq, Thupa, last name also spelled Amaro instead of Amaru) was the last Sapa Inca of the Neo-Inca State, the final remaining independent part of the Inca ...

, its last emperor, in 1572.D'Altroy, ''The Incas'', pp. 319–320.

See also

* List of battles won by Indigenous peoples of the Americas *Encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

* History of Peru

The history of Peru spans 10 millennia, extending back through several stages of cultural development along the country's desert coastline and in the Andes mountains. Peru's coast was home to the Norte Chico civilization, the oldest civilization ...

* Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of ...

* Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spain began colonizing the Americas under the Crown of Castile and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire, with the exception of Brazil, British America, and some small regions ...

Notes

References

* D'Altroy, Terence. ''The Incas''. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002. * Hemming, John. ''The conquest of the Incas''. London:Macmillan

MacMillan, Macmillan, McMillen or McMillan may refer to:

People

* McMillan (surname)

* Clan MacMillan, a Highland Scottish clan

* Harold Macmillan, British statesman and politician

* James MacMillan, Scottish composer

* William Duncan MacMillan ...

, 1993.

* Protzen, Jean-Pierre. ''Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo''. New York: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

, 1993.

* Vega, Juan José. ''Incas contra españoles: treinta batallas''. Lima: Milla Batres, 1980.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ollantaytambo, Battle of

Battles involving Spain

Battles involving the Inca Empire

Conflicts in 1537

1537 in the Inca civilization

16th century in Peru