Battle of Lepanto (1571) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Lepanto was a

p. 83

It was the largest naval battle in Western history since classical antiquity, involving more than 400 warships. Over the following decades, the increasing importance of the

The Christian fleet consisted of 206 galleys and six galleasses (large new galleys with substantial

The Christian fleet consisted of 206 galleys and six galleasses (large new galleys with substantial  Ali Pasha, the Ottoman admiral ('' Kapudan-i Derya''), supported by the corsairs Mehmed Sirocco (natively Mehmed Şuluk) of

Ali Pasha, the Ottoman admiral ('' Kapudan-i Derya''), supported by the corsairs Mehmed Sirocco (natively Mehmed Şuluk) of  Two galleasses, which had side-mounted cannon, were positioned in front of each main division for the purpose, according to

Two galleasses, which had side-mounted cannon, were positioned in front of each main division for the purpose, according to

The wind was at first against the Christians, and it was feared that the Turks would be able to make contact before a line of battle could be formed. But around noon, shortly before contact, the wind shifted to favour the Christians, enabling most of the squadrons to reach their assigned position before contact. Four galeasses stationed in front of the Christian battle line opened fire at close quarters at the foremost Turkish galleys, confusing their battle array in the crucial moment of contact. Around noon, first contact was made between the squadrons of Barbarigo and Sirocco, close to the northern shore of the Gulf. Barbarigo had attempted to stay so close to the shore as to prevent Sirocco from surrounding him, but Sirocco, knowing the depth of the waters, managed to still insert galleys between Barbarigo's line and the coast. In the ensuing mêlée, the ships came so close to each other as to form an almost continuous platform of hand-to-hand fighting in which both leaders were killed. The Christian galley slaves freed from the Turkish ships were supplied with arms and joined in the fighting, turning the battle in favour of the Christian side.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 104.

Meanwhile, the centres clashed with such force that Ali Pasha's galley drove into the ''Real'' as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries. When the ''Real'' was nearly taken, Colonna came alongside, with the bow of his galley, and mounted a counter-attack. With the help of Colonna, the Turks were pushed off the ''Real'' and the Turkish flagship was boarded and swept. The entire crew of Ali Pasha's flagship was killed, including Ali Pasha himself. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and centre, although fighting continued for another two hours.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, pp. 105–06. A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of Saint Stephen, said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still on display, in the Church of the seat of the Order in

The wind was at first against the Christians, and it was feared that the Turks would be able to make contact before a line of battle could be formed. But around noon, shortly before contact, the wind shifted to favour the Christians, enabling most of the squadrons to reach their assigned position before contact. Four galeasses stationed in front of the Christian battle line opened fire at close quarters at the foremost Turkish galleys, confusing their battle array in the crucial moment of contact. Around noon, first contact was made between the squadrons of Barbarigo and Sirocco, close to the northern shore of the Gulf. Barbarigo had attempted to stay so close to the shore as to prevent Sirocco from surrounding him, but Sirocco, knowing the depth of the waters, managed to still insert galleys between Barbarigo's line and the coast. In the ensuing mêlée, the ships came so close to each other as to form an almost continuous platform of hand-to-hand fighting in which both leaders were killed. The Christian galley slaves freed from the Turkish ships were supplied with arms and joined in the fighting, turning the battle in favour of the Christian side.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 104.

Meanwhile, the centres clashed with such force that Ali Pasha's galley drove into the ''Real'' as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries. When the ''Real'' was nearly taken, Colonna came alongside, with the bow of his galley, and mounted a counter-attack. With the help of Colonna, the Turks were pushed off the ''Real'' and the Turkish flagship was boarded and swept. The entire crew of Ali Pasha's flagship was killed, including Ali Pasha himself. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and centre, although fighting continued for another two hours.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, pp. 105–06. A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of Saint Stephen, said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still on display, in the Church of the seat of the Order in

The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. However, the Holy League failed to capitalize on the victory, and while the Ottoman defeat has often been cited as the historical turning-point initiating the eventual stagnation of Ottoman territorial expansion, this was by no means an immediate consequence; even though the Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the ''de facto'' division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies, halting the Ottoman encroachment on Italian territories, the Holy League did not regain any territories that had been lost to the Ottomans prior to Lepanto. Historian Paul K. Davis synopsizes the importance of Lepanto this way: "This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans' expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten"

The Ottomans were quick to rebuild their navy. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean.J. Norwich, ''A History of Venice'', 490 With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire'', 272 Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, even boasted to the Venetian emissary

The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. However, the Holy League failed to capitalize on the victory, and while the Ottoman defeat has often been cited as the historical turning-point initiating the eventual stagnation of Ottoman territorial expansion, this was by no means an immediate consequence; even though the Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the ''de facto'' division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies, halting the Ottoman encroachment on Italian territories, the Holy League did not regain any territories that had been lost to the Ottomans prior to Lepanto. Historian Paul K. Davis synopsizes the importance of Lepanto this way: "This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans' expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten"

The Ottomans were quick to rebuild their navy. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean.J. Norwich, ''A History of Venice'', 490 With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire'', 272 Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, even boasted to the Venetian emissary  The Holy League was disbanded with the peace treaty of 7 March 1573, which concluded the

The Holy League was disbanded with the peace treaty of 7 March 1573, which concluded the

The Holy League credited the victory to the

The Holy League credited the victory to the

There are many pictorial representations of the battle. Prints of the order of battle appeared in Venice and Rome in 1571, and numerous paintings were commissioned, including one in the

There are many pictorial representations of the battle. Prints of the order of battle appeared in Venice and Rome in 1571, and numerous paintings were commissioned, including one in the

File:The Battle of Lepanto by Paolo Veronese.jpeg, ''The Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto'' by

excerpt and text search vol 2

pp 1088–1142 * Chesterton, G. K. ''Lepanto with Explanatory Notes and Commentary'', Dale Ahlquist, ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003). * * Cakir, İbrahim Etem, "Lepanto War and Some Informatıon on the Reconstructıon of The Ottoman Fleet", Turkish Studies – International Periodical For The Language Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic, Volume 4/3 Spring 2009, pp. 512–31 * Contarini, Giovanni Pietro. Kiril Petkov, ed and trans. ''From Cyprus to Lepanto: History of the Events, Which Occurred from the Beginning of the War Brought against the Venetians by Selim the Ottoman, to the Day of the Great and Victorious Battle against the Turks''. Italica Press, 2019. * Cook, M.A. (ed.), "A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730", Cambridge University Press, 1976; * Crowley, Roger ''Empires of the Sea: The siege of Malta, the battle of Lepanto and the contest for the center of the world'', Random House, 2008. * Currey, E. Hamilton, "Sea-Wolves of the Mediterranean", John Murrey, 1910 * * * Guilmartin, John F. (1974) ''Gunpowder & Galleys: Changing Technology & Mediterranean Warfare at Sea in the 16th Century.'' Cambridge University Press, London. . * * Hanson, Victor D. ''Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power'', Anchor Books, 2001. Published in the UK as ''Why the West has Won'', Faber and Faber, 2001. . Includes a chapter about the battle of Lepanto * * * Hess, Andrew C. "The Battle of Lepanto and Its Place in Mediterranean History", ''Past and Present'', No. 57. (Nov., 1972), pp. 53–73 * * Konstam, Angus, ''Lepanto 1571: The Greatest Naval Battle of the Renaissance.'' Osprey Publishing, Oxford. 2003. * * ''Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles'', third revision by George Bruce, 1979 * Parker, Geoffrey (1996) ''The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500–1800.'' (second edition) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. * Stouraiti, Anastasia,

Costruendo un luogo della memoria: Lepanto

, Storia di Venezia – Rivista 1 (2003), 65–88. * Warner, Oliver ''Great Sea Battles'' (1968) has "Lepanto 1571" as its opening chapter. * ''The New Cambridge Modern History, Volume I – The Renaissance 1493–1520'', edited by G. R. Potter, Cambridge University Press 1964 * Wheatcroft, Andrew (2004). ''Infidels: A History of the Conflict between Christendom and Islam''. Penguin Books. * J. P. Jurien de la Gravière,

La Guerre de Chypre et la Bataille de Lépante

' (1888). *

online transcription of pp. 265–71

). * Christopher Check

The Battle that Saved the Christian West

''This Rock'' 18.3 (March 2007). * Lepanto – Rudolph, Harriet

"Die Ordnung der Schlacht und die Ordnung der Erinnerung"

in: ''Militärische Erinnerungskulturen vom 14. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert'' (2012), 101–28. * Guilmartin, John F

in Craig L. Symonds (ed.), ''New Aspects of Naval History: Selected Papers Presented at the Fourth Naval History Symposium, United States Naval Academy 25–26 October 1979'', Annapolis, Maryland: the United States Naval Institute (1981), 41–65.

Battle of Lepanto

''

La batalla de Lepanto

(historia-maritima.blogspot.com, 2012). * Henry Zaidan

(myartblogcollection.blogspot.com, 2016) {{DEFAULTSORT:Lepanto 1571 1571 in the Ottoman Empire 1571 in Italy Conflicts in 1571 History of Aetolia-Acarnania Ionian Sea Nafpaktos Naval battles of the Ottoman–Venetian Wars Naval battles involving the Ottoman Empire Naval battles involving the Republic of Venice Naval battles involving the Republic of Genoa Naval battles involving Savoy Naval battles involving Spain Naval battles involving the Knights Hospitaller Naval battles involving the Papal States

naval engagement

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic state

A Christian state is a country that recognizes a form of Christianity as its official religion and often has a state church (also called an established church), which is a Christian denomination that supports the government and is supported by ...

s (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

) arranged by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

in the Gulf of Patras

The Gulf of Patras ( el, Πατραϊκός Κόλπος, ''Patraikós Kólpos'') is a branch of the Ionian Sea in Western Greece. On the east, it is closed by the Strait of Rion between capes Rio and Antirrio, near the Rio-Antirrio bridge, that ...

. The Ottoman forces were sailing westward from their naval station in Lepanto (the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

name of ancient Naupactus – Greek , Ottoman ) when they met the fleet of the Holy League which was sailing east from Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

and the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

were the main powers of the coalition, as the league was largely financed by Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, and Venice was the main contributor of ships.

In the history of naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

, Lepanto marks the last major engagement in the Western world to be fought almost entirely between rowing vessels, namely the galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be u ...

s and galleasses which were the direct descendants of ancient trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

warships. The battle was in essence an "infantry battle on floating platforms".William Stevens, ''History of Sea Power'' (1920),p. 83

It was the largest naval battle in Western history since classical antiquity, involving more than 400 warships. Over the following decades, the increasing importance of the

galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch ...

and the line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

tactic would displace the galley as the major warship of its era, marking the beginning of the "Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid- 15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the introduction of nava ...

".

The victory of the Holy League is of great importance in the history of Europe and of the Ottoman Empire, marking the turning-point of Ottoman military expansion into the Mediterranean, although the Ottoman wars in Europe

A series of military conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and various European states took place from the Late Middle Ages up through the early 20th century. The earliest conflicts began during the Byzantine–Ottoman wars, waged in Anatolia in ...

would continue for another century. It has long been compared to the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

, both for tactical parallels and for its crucial importance in the defense of Europe against imperial expansion. It was also of great symbolic importance in a period when Europe was torn by its own wars of religion

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

following the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

. Pope Pius V instituted the feast of Our Lady of Victory

Our or OUR may refer to:

* The possessive form of " we"

* Our (river), in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany

* Our, Belgium, a village in Belgium

* Our, Jura, a commune in France

* Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR), a government utility regulato ...

, and Philip II of Spain used the victory to strengthen his position as the " Most Catholic King" and defender of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

against Muslim incursion. Historian Paul K. Davis writes that

More than a military victory, Lepanto was a moral one. For decades, the Ottoman Turks had terrified Europe, and the victories ofSuleiman the Magnificent Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...caused Christian Europe serious concern. The defeat at Lepanto further exemplified the rapid deterioration of Ottoman might underSelim II Selim II (Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى ''Selīm-i sānī'', tr, II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond ( tr, Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunk ( tr, Sarhoş Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire f ..., and Christians rejoiced at this setback for the Ottomans. The mystique of Ottoman power was tarnished significantly by this battle, and Christian Europe was heartened.

Background

The Christian coalition had been promoted byPope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

to rescue the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

colony of Famagusta

Famagusta ( , ; el, Αμμόχωστος, Ammóchostos, ; tr, Gazimağusa or ) is a city on the east coast of Cyprus. It is located east of Nicosia and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under t ...

on the island of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, which was being besieged by the Turks in early 1571 subsequent to the fall of Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaori ...

and other Venetian possessions in Cyprus in the course of 1570. On 1 August the Venetians had surrendered after being reassured that they could leave Cyprus freely. However, the Ottoman commander, Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha

Lala Mustafa Pasha ( – 7 August 1580), also known by the additional epithet ''Kara'', was an Ottoman Bosnian general and Grand Vizier from the Sanjak of Bosnia.

Life

He was born around 1500, near the Glasinac in Sokolac Plateau in Bosnia t ...

, who had lost some 50,000 men in the siege, broke his word, imprisoning the Venetians. On 17 August Marco Antonio Bragadin was flayed alive and his corpse hung on Mustafa's galley together with the heads of the Venetian commanders, Astorre Baglioni

Astorre Baglioni (March 1526 – 4 August 1571) was an Italian condottiero and military commander.

Biography

He was born in Perugia, the son of Gentile Baglioni, a member of a condottieri family of central Italy. At the death of his father, ...

, Alvise Martinengo, and Gianantonio Querini.

The members of the Holy League were the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

, the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

(including the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

, the Kingdoms of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

as part of the Spanish possessions), the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

, the Duchies of Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

, Urbino

Urbino ( ; ; Romagnol: ''Urbìn'') is a walled city in the Marche region of Italy, south-west of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially under the patronage of F ...

and Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

, and others.

The banner for the fleet, blessed by the Pope, reached the Kingdom of Naples (then ruled by Philip II of Spain) on 14 August 1571. There, in the Basilica of Santa Chiara, it was solemnly consigned to John of Austria

John of Austria ( es, Juan, link=no, german: Johann; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the natural son born to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V late in life when he was a widower. Charles V met his son only once, recognizing him in a secret ...

, who had been named the leader of the coalition after long discussions among the allies. The fleet moved to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and, leaving Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, reached (after several stops) the port of Viscardo in Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It ...

, where news arrived of the fall of Famagusta and of the torture inflicted by the Turks on the Venetian commander of the fortress, Marco Antonio Bragadin.

All members of the alliance viewed the Ottoman navy as a significant threat, both to the security of maritime trade in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

and to the security of continental Europe itself. Spain was the largest financial contributor, though the Spaniards preferred to preserve most of their galleys for Spain's own wars against the nearby sultanates of the Barbary Coast rather than expend its naval strength for the benefit of Venice. Setton (1984), p. 1047. Meyer Setton, Kenneth: ''The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571'', Vol. IV. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1984. , p. 1047. The combined Christian fleet was placed under the command of John of Austria (Don Juan de Austria) with Marcantonio Colonna as his principal deputy. The various Christian contingents met the main force, that of Venice (under Sebastiano Venier

Sebastiano Venier (or Veniero) (c. 1496 – 3 March 1578) was Doge of Venice from 11 June 1577 to 3 March 1578. He is best remembered in his role as the Venetian admiral at the Battle of Lepanto.

Biography

Venier was born in Venice around 1496. H ...

, later Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

), in July and August 1571 at Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

.

Deployment and order of battle

The Christian fleet consisted of 206 galleys and six galleasses (large new galleys with substantial

The Christian fleet consisted of 206 galleys and six galleasses (large new galleys with substantial artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

, developed by the Venetians) and was commanded by Spanish Admiral John of Austria

John of Austria ( es, Juan, link=no, german: Johann; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the natural son born to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V late in life when he was a widower. Charles V met his son only once, recognizing him in a secret ...

, the illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

son of Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

and half-brother of King Philip II of Spain, supported by the Spanish commanders Don Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga

Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga (25 August 1528 – 5 March 1576) was a Spanish general, sailor, diplomat and politician. He served as governor of the Duchy of Milan (1572–1573) and as governor of the Spanish Netherlands (1573–1576).

Biography

...

and Don Álvaro de Bazán Álvaro (, , ) is a Spanish, Galician and Portuguese male given name and surname (see Spanish naming customs) of Visigothic origin. Some claim it may be related to the Old Norse name Alfarr, formed of the elements ''alf'' "elf" and ''arr'' "warrior ...

, and Genoan commander Gianandrea Doria. Stevens (1942), pp. 66–69 The Republic of Venice contributed 109 galleys and six galleasses, 49 galleys came from the Spanish Empire (including 26 from the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily, and other Italian territories), 27 galleys of the Genoese fleet

The Genoese navy was the naval contingent of the Republic of Genoa's military. From the 11th century onward the Genoese navy protected the interests of the republic and projected its power throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas. It played ...

, seven galleys from the Papal States, five galleys from the Order of Saint Stephen and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, three galleys each from the Duchy of Savoy and the Knights of Malta, and some privately owned galleys in Spanish service. This fleet of the Christian alliance was manned by 40,000 sailors and oarsmen. In addition, it carried approximately 30,000, p. 263 fighting troops: 7,000 Spanish Empire regular infantry of excellent quality,

(4,000 of the Spanish Empire's troops were drawn from the Kingdom of Naples, mostly Calabria), 7,000 Germans, Setton (1984), p. 1026 6,000 Italian mercenaries in Spanish pay, all good troops, in addition to 5,000 professional Venetian soldiers. Also, Venetian oarsmen were mainly free citizens and able to bear arms, adding to the fighting power of their ships, whereas convicts were used to row many of the galleys in other Holy League squadrons.John F. Guilmartin (1974), pp. 222–25

Free oarsmen were generally acknowledged to be superior but were gradually replaced in all galley fleets (including those of Venice from 1549) during the 16th century by cheaper slaves, convicts, and prisoners-of-war owing to rapidly rising costs.

Ali Pasha, the Ottoman admiral ('' Kapudan-i Derya''), supported by the corsairs Mehmed Sirocco (natively Mehmed Şuluk) of

Ali Pasha, the Ottoman admiral ('' Kapudan-i Derya''), supported by the corsairs Mehmed Sirocco (natively Mehmed Şuluk) of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

and Uluç Ali, commanded an Ottoman force of 222 war galleys, 56 galliots

A galiot, galliot or galiote, was a small galley boat propelled by sail or oars. There are three different types of naval galiots that sailed on different seas.

A ''galiote'' was a type of French flat-bottom river boat or barge and also a flat- ...

, and some smaller vessels. The Turks had skilled and experienced crews of sailors but were significantly deficient in their elite corps of Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

. The number of oarsmen was about 37,000, virtually all of them slaves, many of them Christians who had been captured in previous conquests and engagements. The Ottoman galleys were manned by 13,000 experienced sailors—generally drawn from the maritime nations of the Ottoman Empire—mainly Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

, Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

ns, and Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

—and 25,000 soldiers from Ottoman Empire as well as few thousands from their North African allies. Stevens (1942), p. 63

While soldiers on board of the ships were roughly evenly matched in numbers, an advantage for the Christians was the numerical superiority in guns and cannon aboard their ships. It is estimated that the Christians had 1,815 guns, while the Turks had only 750 with insufficient ammunition. The Christians embarked with their much improved arquebusier

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbu ...

and musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pr ...

forces, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bow

A composite bow is a traditional bow made from horn, wood, and sinew laminated together, a form of laminated bow. The horn is on the belly, facing the archer, and sinew on the outer side of a wooden core. When the bow is drawn, the sinew (stre ...

men.

The Christian fleet started from Messina on 16 September, crossing the Adriatic and creeping along the coast, arriving at the group of rocky islets lying just north of the opening of the Gulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf ( el, Κορινθιακός Kόλπος, ''Korinthiakόs Kόlpos'', ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the ...

on 6 October. Serious conflict had broken out between Venetian and Spanish soldiers, and Venier enraged Don Juan by hanging a Spanish soldier for impudence.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 103. Despite bad weather, the Christian ships sailed south and, on 6 October, reached the port of Sami, Cephalonia

Sami ( el, Σάμη) is a town and a municipality on the island of Cephalonia, Ionian Islands, Greece. Since the 2019 local government reform it is one of the three municipalities on the island. It is located on the central east coast of the isla ...

(then also called Val d'Alessandria), where they remained for a while.

Early on 7 October, they sailed toward the Gulf of Patras

The Gulf of Patras ( el, Πατραϊκός Κόλπος, ''Patraikós Kólpos'') is a branch of the Ionian Sea in Western Greece. On the east, it is closed by the Strait of Rion between capes Rio and Antirrio, near the Rio-Antirrio bridge, that ...

, where they encountered the Ottoman fleet. While neither fleet had immediate strategic resources or objectives in the gulf, both chose to engage. The Ottoman fleet had an express order from the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

to fight, and John of Austria found it necessary to attack in order to maintain the integrity of the expedition in the face of personal and political disagreements within the Holy League. On the morning of 7 October, after the decision to offer battle was made, the Christian fleet formed up in four divisions in a north–south line:

* At the northern end, closest to the coast, was the Left Division of 53 galleys, mainly Venetian, led by Agostino Barbarigo

Agostino Barbarigo (3 June 1419 – 20 September 1501) was Doge of Venice from 1486 until his death in 1501.

While he was Doge, the imposing Clock Tower in the Piazza San Marco with its archway through which the street known as the Merceria le ...

, with Marco Querini and Antonio da Canale in support.

* The Centre Division consisted of 62 galleys under John of Austria himself in his ''Real

Real may refer to:

Currencies

* Brazilian real (R$)

* Central American Republic real

* Mexican real

* Portuguese real

* Spanish real

* Spanish colonial real

Music Albums

* ''Real'' (L'Arc-en-Ciel album) (2000)

* ''Real'' (Bright album) (2010) ...

'', along with Marcantonio Colonna commanding the papal flagship, Venier commanding the Venetian flagship, Paolo Giordano I Orsini

Paolo Giordano Orsini (1541 – 13 November 1585) was an Italian nobleman, and the first duke of Bracciano from 1560. He was a member of the Roman family of the Orsini.

Biography

The son of Girolamo Orsini and Francesca Sforza, he was grandson, ...

and Pietro Giustiniani, prior of Messina, commanding the flagship of the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

.

* The Right Division to the south consisted of another 53 galleys under the Genoese Giovanni Andrea Doria

Giovanni Andrea Doria, also known as Gianandrea Doria, (1539–1606), was an Italian admiral from Genoa.

Biography

Doria was born to a noble family of the Republic of Genoa. He was the son of Giannettino Doria, of the Doria family, who died whe ...

, great-nephew of admiral Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Rep ...

.

* A Reserve Division was stationed behind (that is, to the west of) the main fleet, to lend support wherever it might be needed, commanded by Álvaro de Bazán Álvaro (, , ) is a Spanish, Galician and Portuguese male given name and surname (see Spanish naming customs) of Visigothic origin. Some claim it may be related to the Old Norse name Alfarr, formed of the elements ''alf'' "elf" and ''arr'' "warrior ...

.

Two galleasses, which had side-mounted cannon, were positioned in front of each main division for the purpose, according to

Two galleasses, which had side-mounted cannon, were positioned in front of each main division for the purpose, according to Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

(who served on the galley ''Marquesa'' during the battle), of preventing the Turks from sneaking in small boats and sapping, sabotaging, or boarding the Christian vessels. This reserve division consisted of 38 galleys—30 behind the Centre Division and four behind each wing. A scouting group was formed, from two Right Wing and six Reserve Division galleys. As the Christian fleet was slowly turning around Point Scropha, Doria's Right Division, at the offshore side, was delayed at the start of the battle and the Right's galleasses did not get into position.

The Ottoman fleet consisted of 57 galleys and two galliots on its right under Mehmed Siroco, 61 galleys and 32 galliots in the centre under Ali Pasha in the ''Sultana'', and about 63 galleys and 30 galliots in the south offshore under Uluç Ali. A small reserve consisted of eight galleys, 22 galliots, and 64 fusta

The fusta or fuste (also called foist) was a narrow, light and fast ship with shallow draft, powered by both oars and sail—in essence a small galley. It typically had 12 to 18 two-man rowing benches on each side, a single mast with a lateen ( ...

s, behind the centre body. Ali Pasha is supposed to have told his Christian galley slaves, "If I win the battle, I promise you your liberty. If the day is yours, then God has given it to you." John of Austria, more laconically, warned his crew, "There is no paradise for cowards." Stevens (1942), p. 64

Battle

The lookout on the ''Real'' sighted the Turkish van at dawn of 7 October. Don Juan called a council of war and decided to offer battle. He travelled through his fleet in a swift sailing vessel, exhorting his officers and men to do their utmost. The Sacrament was administered to all, the galley slaves were freed from their chains, and the standard of the Holy League was raised to the truck of the flagship. The wind was at first against the Christians, and it was feared that the Turks would be able to make contact before a line of battle could be formed. But around noon, shortly before contact, the wind shifted to favour the Christians, enabling most of the squadrons to reach their assigned position before contact. Four galeasses stationed in front of the Christian battle line opened fire at close quarters at the foremost Turkish galleys, confusing their battle array in the crucial moment of contact. Around noon, first contact was made between the squadrons of Barbarigo and Sirocco, close to the northern shore of the Gulf. Barbarigo had attempted to stay so close to the shore as to prevent Sirocco from surrounding him, but Sirocco, knowing the depth of the waters, managed to still insert galleys between Barbarigo's line and the coast. In the ensuing mêlée, the ships came so close to each other as to form an almost continuous platform of hand-to-hand fighting in which both leaders were killed. The Christian galley slaves freed from the Turkish ships were supplied with arms and joined in the fighting, turning the battle in favour of the Christian side.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 104.

Meanwhile, the centres clashed with such force that Ali Pasha's galley drove into the ''Real'' as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries. When the ''Real'' was nearly taken, Colonna came alongside, with the bow of his galley, and mounted a counter-attack. With the help of Colonna, the Turks were pushed off the ''Real'' and the Turkish flagship was boarded and swept. The entire crew of Ali Pasha's flagship was killed, including Ali Pasha himself. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and centre, although fighting continued for another two hours.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, pp. 105–06. A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of Saint Stephen, said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still on display, in the Church of the seat of the Order in

The wind was at first against the Christians, and it was feared that the Turks would be able to make contact before a line of battle could be formed. But around noon, shortly before contact, the wind shifted to favour the Christians, enabling most of the squadrons to reach their assigned position before contact. Four galeasses stationed in front of the Christian battle line opened fire at close quarters at the foremost Turkish galleys, confusing their battle array in the crucial moment of contact. Around noon, first contact was made between the squadrons of Barbarigo and Sirocco, close to the northern shore of the Gulf. Barbarigo had attempted to stay so close to the shore as to prevent Sirocco from surrounding him, but Sirocco, knowing the depth of the waters, managed to still insert galleys between Barbarigo's line and the coast. In the ensuing mêlée, the ships came so close to each other as to form an almost continuous platform of hand-to-hand fighting in which both leaders were killed. The Christian galley slaves freed from the Turkish ships were supplied with arms and joined in the fighting, turning the battle in favour of the Christian side.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 104.

Meanwhile, the centres clashed with such force that Ali Pasha's galley drove into the ''Real'' as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries. When the ''Real'' was nearly taken, Colonna came alongside, with the bow of his galley, and mounted a counter-attack. With the help of Colonna, the Turks were pushed off the ''Real'' and the Turkish flagship was boarded and swept. The entire crew of Ali Pasha's flagship was killed, including Ali Pasha himself. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and centre, although fighting continued for another two hours.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, pp. 105–06. A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of Saint Stephen, said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still on display, in the Church of the seat of the Order in Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

.

On the Christian right, the situation was different, as Doria continued sailing towards the south instead of taking his assigned position. He would explain his conduct after the battle by saying that he was trying to prevent an enveloping manoeuvre by the Turkish left. But Doria's captains were enraged, interpreting their commander's signals as a sign of treachery. When Doria had opened a wide gap with the Christian centre, Uluç Ali swung around and fell on Colonna's southern flank, with Doria too far away to interfere. Ali attacked a group of some fifteen galleys around the flagship of the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

, threatening to break into the Christian centre and still turn the tide of the battle. This was prevented by the arrival of the reserve squadron of Santa Cruz. Uluç Ali was forced to retreat, escaping the battle with the captured flag of the Knights of Malta.

Isolated fighting continued until the evening. Even after the battle had clearly turned against the Turks, groups of janissaries kept fighting to the last. It is said that at some point the Janissaries ran out of weapons and started throwing oranges and lemons at their Christian adversaries, leading to awkward scenes of laughter among the general misery of battle. At the end of the battle, the Christians had taken 117 galleys and 20 galliots, and sunk or destroyed some 50 other ships. Around ten thousand Turks were taken prisoner, and many thousands of Christian slaves were rescued. The Christian side suffered around 7,500 deaths, the Turkish side about 30,000.William Oliver Stevens and Allan F. Westcott, ''A History of Sea Power'', 1920, p. 107.

Aftermath

The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. However, the Holy League failed to capitalize on the victory, and while the Ottoman defeat has often been cited as the historical turning-point initiating the eventual stagnation of Ottoman territorial expansion, this was by no means an immediate consequence; even though the Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the ''de facto'' division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies, halting the Ottoman encroachment on Italian territories, the Holy League did not regain any territories that had been lost to the Ottomans prior to Lepanto. Historian Paul K. Davis synopsizes the importance of Lepanto this way: "This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans' expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten"

The Ottomans were quick to rebuild their navy. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean.J. Norwich, ''A History of Venice'', 490 With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire'', 272 Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, even boasted to the Venetian emissary

The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. However, the Holy League failed to capitalize on the victory, and while the Ottoman defeat has often been cited as the historical turning-point initiating the eventual stagnation of Ottoman territorial expansion, this was by no means an immediate consequence; even though the Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the ''de facto'' division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies, halting the Ottoman encroachment on Italian territories, the Holy League did not regain any territories that had been lost to the Ottomans prior to Lepanto. Historian Paul K. Davis synopsizes the importance of Lepanto this way: "This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans' expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten"

The Ottomans were quick to rebuild their navy. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean.J. Norwich, ''A History of Venice'', 490 With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire'', 272 Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, even boasted to the Venetian emissary Marcantonio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro (1518–1595) was an Italian diplomat of the Republic of Venice.

Family

He was born in Venice into the aristocratic Barbaro family. His father was Francesco di Daniele Barbaro and his mother Elena Pisani, daughter of the banke ...

that the Christian triumph at Lepanto caused no lasting harm to the Ottoman Empire, while the capture of Cyprus by the Ottomans in the same year was a significant blow, saying that:

In 1572, the allied Christian fleet resumed operations and faced a renewed Ottoman navy of 200 vessels under Kılıç Ali Pasha, but the Ottoman commander actively avoided engaging the allied fleet and headed for the safety of the fortress of Modon The Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones ( ar, الهيئة السعودية للمدن الصناعية ومناطق التقنية), also known simply as MODON ( ar, مُدُن) is a government organization created by the Go ...

. The arrival of the Spanish squadron of 55 ships evened the numbers on both sides and opened the opportunity for a decisive blow, but friction among the Christian leaders and the reluctance of Don Juan squandered the opportunity.

Pius V died on 1 May 1572. The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to unravel. In 1573, the Holy League fleet failed to sail altogether; instead, Don Juan attacked and took Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, only for it to be retaken by the Ottomans in 1574. Venice, fearing the loss of its Dalmatian possessions and a possible invasion of Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

, and eager to cut its losses and resume the trade with the Ottoman Empire, initiated unilateral negotiations with the Porte

Porte may refer to:

*Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman empire

*Porte, Piedmont, a municipality in the Piedmont region of Italy

*John Cyril Porte, British/Irish aviator

*Richie Porte, Australian professional cyclist who competes ...

.

The Holy League was disbanded with the peace treaty of 7 March 1573, which concluded the

The Holy League was disbanded with the peace treaty of 7 March 1573, which concluded the War of Cyprus

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

. Venice was forced to accept loser's terms in spite of the victory at Lepanto. Cyprus was formally ceded to the Ottoman Empire, and Venice agreed to pay an indemnity of 300,000 ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained ...

s. In addition, the border between the two powers in Dalmatia was modified by the Turkish occupation of small but important parts of the hinterland that included the most fertile agricultural areas near the cities, with adverse effects on the economy of the Venetian cities in Dalmatia. Peace would hold between the two states until the Cretan War of 1645.

In 1574, the Ottomans retook the strategic city of Tunis from the Spanish-supported Hafsid

The Hafsids ( ar, الحفصيون ) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. who ruled Ifriqiya (western ...

dynasty, which had been re-installed after John of Austria's forces reconquered the city from the Ottomans the year before. Thanks to the long-standing Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was o ...

, the Ottomans were able to resume naval activity in the western Mediterranean. In 1576, the Ottomans assisted in Abdul Malik's capture of Fez – this reinforced the Ottoman indirect conquests in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

that had begun under Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

. The establishment of Ottoman suzerainty over the area placed the entire southern coast of the Mediterranean from the Straits of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaism, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to ...

to Greece under Ottoman authority, with the exceptions of the Spanish-controlled trading city of Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

and strategic settlements such as Melilla

Melilla ( , ; ; rif, Mřič ; ar, مليلية ) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was pa ...

and Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territori ...

. But after 1580, the Ottoman Empire could no longer compete with the advances in European naval technology, especially the development of the galleon and line of battle tactics used in the Spanish Navy. Spanish success in the Mediterranean continued into the first half of the 17th century. Spanish ships attacked the Anatolian coast, defeating larger Ottoman fleets at the Battle of Cape Celidonia and the Battle of Cape Corvo

The Battle of Cape Corvo was a naval engagement of the Ottoman–Habsburg wars fought as part of the struggle for the control of the Mediterranean. It took place in August 1613 near the island of Samos when a Spanish squadron from Sicily, under A ...

. Larache

Larache ( ar, العرايش, al-'Araysh) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast, where the Loukkos River meets the Atlantic Ocean. Larache is one of the most important cities of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region.

Man ...

and La Mamora

Mehdya ( ar-at, المهدية, al-Mahdiyā), also Mehdia or Mehedya, is a town in Kénitra Province, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, Morocco. Previously called al-Ma'mura, it was known as São João da Mamora under 16th century Portuguese occupation, or ...

, in the Moroccan Atlantic coast, and the island of Alhucemas, in the Mediterranean, were taken (although Larache and La Mamora were lost again later in the 17th century). Ottoman expansion in the 17th century shifted to land war with Austria on one hand, culminating in the Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

of 1683–1699, and to the war with Safavid Persia on the other.

Legacy

Accounts

Giovanni Pietro Contarini's ''History of the Events, which occurred from the Beginning of the War Brought against the Venetians by Selim the Ottoman, to the Day of the Great and Victorious Battle against the Turks'' was published in 1572, a few months after Lepanto. It was the first comprehensive account of the war, and the only one to attempt a concise but complete overview of its course and the Holy League's triumph. Contarini's account went beyond effusive praise and mere factual reporting to examine the meaning and importance of these events. It is also the only full historical account by an immediate commentator, blending his straightforward narrative with keen and consistent reflections on the political philosophy of conflict in the context of the Ottoman-Catholic confrontation in the early modern Mediterranean.Commemoration

The Holy League credited the victory to the

The Holy League credited the victory to the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, whose intercession

Intercession or intercessory prayer is the act of praying to a deity on behalf of others, or asking a saint in heaven to pray on behalf of oneself or for others.

The Apostle Paul's exhortation to Timothy specified that intercession prayers sh ...

with God they had implored for victory through the use of the Rosary

The Rosary (; la, , in the sense of "crown of roses" or "garland of roses"), also known as the Dominican Rosary, or simply the Rosary, refers to a set of prayers used primarily in the Catholic Church, and to the physical string of knots or ...

. Andrea Doria had kept a copy of the miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe given to him by King Philip II of Spain in his ship's state room. Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

instituted a new Catholic feast day of Our Lady of Victory to commemorate the battle, which is now celebrated by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

as the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary

Our Lady of the Rosary, also known as Our Lady of the Holy Rosary, is a Marian title.

The Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, formerly known as Feast of Our Lady of Victory and Feast of the Holy Rosary is celebrated on 7 October in the General Rom ...

. Dominican friar Juan Lopez in his 1584 book on the rosary states that the feast of the rosary was offered "in memory and in perpetual gratitude of the miraculous victory that the Lord gave to his Christian people that day against the Turkish armada".A piece of commemorative music composed after the victory is the motet ''Canticum Moysis'' ( Song of Moses Exodus 15) ''Pro victoria navali contra Turcas'' by the Spanish composer based in Rome

Fernando de las Infantas

Fernando de las Infantas (1534ca. 1610) was a Spanish nobleman, composer and theologian.

Life

Infantas was born in Córdoba in 1534, a descendant of Juan Fernández de Córdoba who had conveyed the two daughters, ''infantas'' (hence the surname), ...

. The other piece of music is Jacobus de Kerle

Jacobus de Kerle (Ypres 1531/1532 - Prague 7 January 1591) was a Flemish composer and organist of the late Renaissance.

Life

De Kerle was trained at the monastery of St. Martin in Ypres, and held positions as a singer in Cambrai and choirmaster in ...

's "Cantio octo vocum de sacro foedere contra Turcas" 1572 (Song in Eight Voices on the Holy League Against the Turks), in the opinion of Pettitt (2006) an "exuberantly militaristic" piece celebrating the victory. There were celebrations and festivities with ''triumphs'' and pageants at Rome and Venice with Turkish slaves in chains.

The fortress of Palmanova in Italy originally called ''Palma'' was built by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

on 7 October 1593 to commemorate the victory.

Paintings

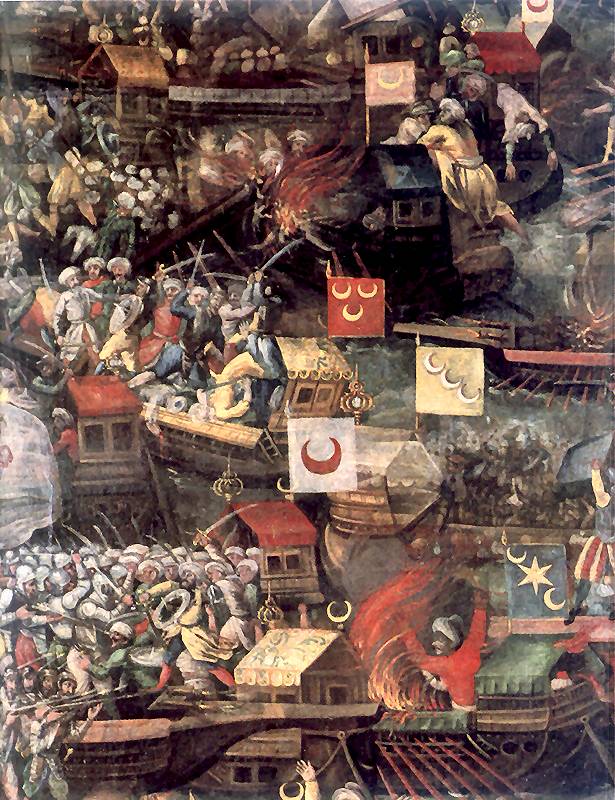

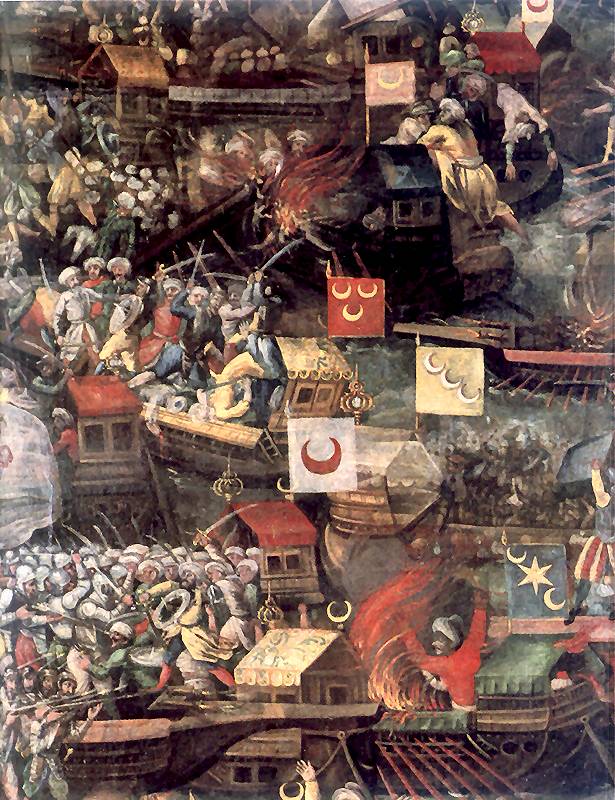

There are many pictorial representations of the battle. Prints of the order of battle appeared in Venice and Rome in 1571, and numerous paintings were commissioned, including one in the

There are many pictorial representations of the battle. Prints of the order of battle appeared in Venice and Rome in 1571, and numerous paintings were commissioned, including one in the Doge's Palace, Venice

The Doge's Palace ( it, Palazzo Ducale; vec, Pałaso Dogal) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace was the residence of the Doge of Venice, the supreme aut ...

, by Andrea Vicentino

Andrea Vicentino (c. 1542 – 1617) was an Italian painter of the late- Renaissance or Mannerist period. He was a pupil of the painter Giovanni Battista Maganza. Born in Vicenza, he was also known as ''Andrea Michieli'' or ''Michelli''. He mo ...

on the walls of the ''Sala dello Scrutinio'', which replaced Tintoretto

Tintoretto ( , , ; born Jacopo Robusti; late September or early October 1518Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.31 May 1594) was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed wit ...

's ''Victory of Lepanto'', destroyed by fire in 1577. Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

painted the battle in the background of an allegorical work showing Philip II of Spain holding his infant son, Don Fernando

Don Fernando (born April 12, 1948) is a director and actor of pornographic films. He started in the pornography business in 1977 and performed for 39 consecutive years; the longest tenure for any male pornographic film actor in the world, until ...

, his male heir born shortly after the victory, on 4 December 1571. An angel descends from heaven bearing a palm branch with a motto for Fernando, who is held up by Philip: "Majora tibi" (may you achieve greater deeds; Fernando died as a child, in 1578).

''The Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto'' (c. 1572, oil on canvas, 169 x 137 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia

The Gallerie dell'Accademia is a museum gallery of pre-19th-century art in Venice, northern Italy. It is housed in the Scuola della Carità on the south bank of the Grand Canal, within the sestiere of Dorsoduro. It was originally the gallery o ...

, Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

) is a painting by Paolo Veronese

Paolo Caliari (152819 April 1588), known as Paolo Veronese ( , also , ), was an Italian Renaissance painter based in Venice, known for extremely large history paintings of religion and mythology, such as '' The Wedding at Cana'' (1563) and ''T ...

. The lower half of the painting shows the events of the battle, whilst at the top a female personification of Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

is presented to the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, with Saint Roch

Roch (lived c. 1348 – 15/16 August 1376/79 (traditionally c. 1295 – 16 August 1327, also called Rock in English, is a Catholic saint, a confessor whose death is commemorated on 16 August and 9 September in Italy; he is especially invoked a ...

, Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

, Saint Justina, Saint Mark and a group of angels in attendance.

A painting by Wenceslas Cobergher

Wenceslas Cobergher (1560 – 23 November 1634), sometimes called Wenzel Coebergher, was a Flemish Renaissance architect, engineer, painter, antiquarian, numismatist and economist. Faded somewhat into the background as a painter, he is chiefly ...

, dated to the end of the 16th century, now in San Domenico Maggiore

San Domenico Maggiore is a Gothic, Roman Catholic church and monastery, founded by the friars of the Dominican Order, and located in the square of the same name in the historic center of Naples.

History

The square is bordered by a street/alle ...

, shows what is interpreted as a victory procession in Rome on the return of admiral Colonna. On the stairs of Saint Peter's Basilica, Pius V is visible in front of a kneeling figure, identified as Marcantonio Colonna returning the standard of the Holy League to the pope. On high is the Madonna and child with victory palms.

Tommaso Dolabella

Tommaso Dolabella ( pl, Tomasz Dolabella; 1570 – 17 January 1650) was a Baroque Italian painter from Venice, who settled in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the royal court of King Sigismund III Vasa.

Active in the historical capita ...

painted his ''The Battle of Lepanto'' in c. 1625–1630 on the commission of Stanisław Lubomirski, commander of the Polish left wing in the Battle of Khotyn (1621)

The Battle of Khotyn or Battle of Chocim or Hotin War (in Turkish: ''Hotin Muharebesi'') was a combined siege and series of battles which took place between 2 September and 9 October 1621 between a Polish-Lithuanian army with Cossack allies, c ...

. The monumental painting (3.05 m × 6.35 m) combines the Polish victory procession following this battle with the backdrop of the Battle of Lepanto. It was later owned by the Dominicans of Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

and since 1927 has been on display in Wawel Castle

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established ...

, Cracow.

'' The Battle of Lepanto'' by Juan Luna

Juan Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta (, ; October 23, 1857 – December 7, 1899) was a Filipino painter, sculptor and a political activist of the Philippine Revolution during the late 19th century. He became one of the first recogni ...

(1887) is displayed at the Spanish Senate in Madrid.

Paolo Veronese

Paolo Caliari (152819 April 1588), known as Paolo Veronese ( , also , ), was an Italian Renaissance painter based in Venice, known for extremely large history paintings of religion and mythology, such as '' The Wedding at Cana'' (1563) and ''T ...

(c. 1572, Gallerie dell'Accademia

The Gallerie dell'Accademia is a museum gallery of pre-19th-century art in Venice, northern Italy. It is housed in the Scuola della Carità on the south bank of the Grand Canal, within the sestiere of Dorsoduro. It was originally the gallery o ...

, Venice)

File:Battle of Lepanto 1595-1605 Andrea Vicentino.jpg, ''The Battle of Lepanto'' by Andrea Vicentino (c. 1600, Doge's Palace

The Doge's Palace ( it, Palazzo Ducale; vec, Pałaso Dogal) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace was the residence of the Doge of Venice, the supreme aut ...

, Venice)

File:Lepanto Dolabella.jpg, ''The Battle of Lepanto'' by Tommaso Dolabella

Tommaso Dolabella ( pl, Tomasz Dolabella; 1570 – 17 January 1650) was a Baroque Italian painter from Venice, who settled in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the royal court of King Sigismund III Vasa.

Active in the historical capita ...

(c. 1625–1630, Wawel Castle

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established ...

, Cracow)

File:'The Battle of Lepanto', painting by Andries van Eertvelt.jpg, ''The Battle of Lepanto'' by Andries van Eertvelt (1640)

File:The Battle of Lepanto of 1571 full version by Juan Luna.jpg, ''The Battle of Lepanto'' by Juan Luna

Juan Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta (, ; October 23, 1857 – December 7, 1899) was a Filipino painter, sculptor and a political activist of the Philippine Revolution during the late 19th century. He became one of the first recogni ...

(1887, Spanish Senate, Madrid)