Battle of Hampton Roads on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

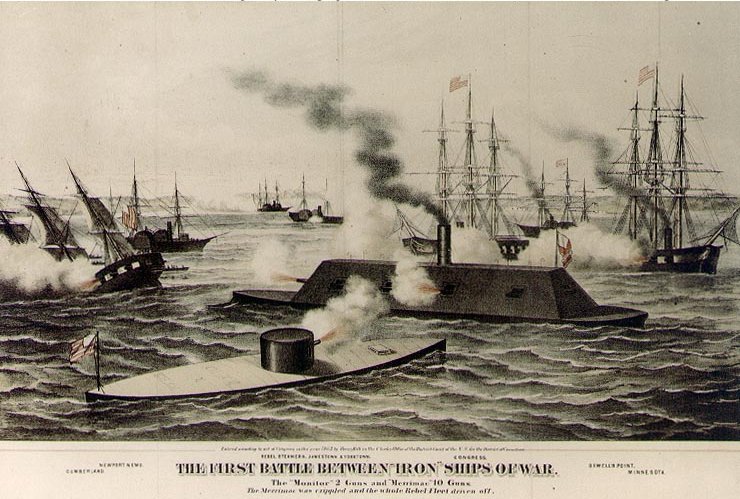

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the

On April 19, 1861, shortly after the outbreak of hostilities at

On April 19, 1861, shortly after the outbreak of hostilities at

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Confederate

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Confederate

Intelligence that the Confederates were working to develop an ironclad caused consternation for the Union, but Secretary of the Navy

Intelligence that the Confederates were working to develop an ironclad caused consternation for the Union, but Secretary of the Navy

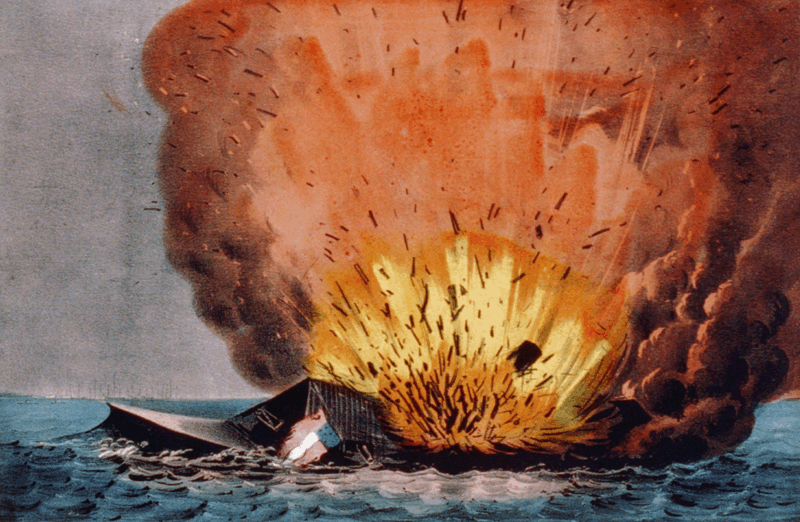

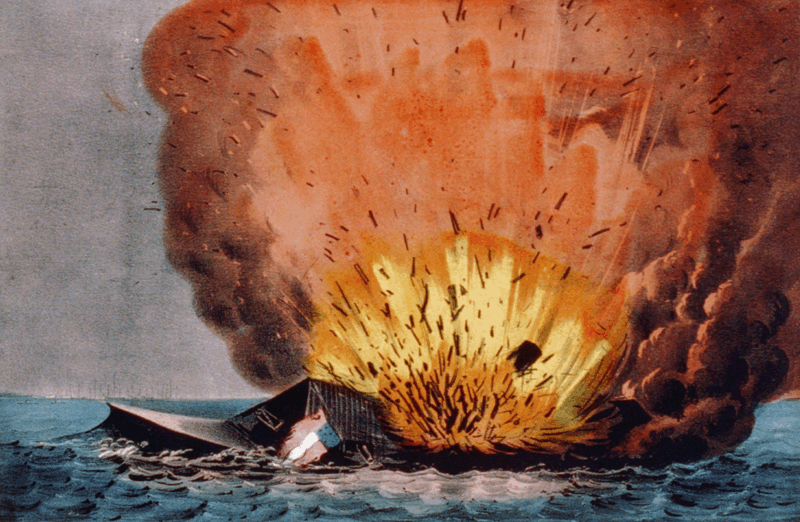

Buchanan next turned ''Virginia'' on ''Congress''. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith, captain of ''Congress'', ordered his ship grounded in shallow water. By this time, the James River Squadron, commanded by John Randolph Tucker, had arrived and joined ''Virginia'' in the attack on ''Congress''. After an hour of unequal combat, the badly damaged ''Congress'' surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. In retaliation, Buchanan ordered ''Congress'' fired upon with hot shot, cannonballs heated red-hot. ''Congress'' caught fire and burned throughout the rest of the day. Near midnight, the flames reached her magazine and she exploded and sank, stern first. Personnel losses included 110 killed or missing and presumed drowned. Another 26 were wounded, of whom ten died within days.

Although she had not suffered anything like the damage she had inflicted, ''Virginia'' was not completely unscathed. Shots from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and Union troops ashore had riddled her smokestack, reducing her already low speed. Two of her guns were disabled and several armor plates had been loosened. Two of her crew were killed, and more were wounded. One of the wounded was Captain Buchanan, whose left thigh was pierced by a rifle shot.

Meanwhile, the James River Squadron had turned its attention to ''Minnesota'', which had left

Buchanan next turned ''Virginia'' on ''Congress''. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith, captain of ''Congress'', ordered his ship grounded in shallow water. By this time, the James River Squadron, commanded by John Randolph Tucker, had arrived and joined ''Virginia'' in the attack on ''Congress''. After an hour of unequal combat, the badly damaged ''Congress'' surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. In retaliation, Buchanan ordered ''Congress'' fired upon with hot shot, cannonballs heated red-hot. ''Congress'' caught fire and burned throughout the rest of the day. Near midnight, the flames reached her magazine and she exploded and sank, stern first. Personnel losses included 110 killed or missing and presumed drowned. Another 26 were wounded, of whom ten died within days.

Although she had not suffered anything like the damage she had inflicted, ''Virginia'' was not completely unscathed. Shots from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and Union troops ashore had riddled her smokestack, reducing her already low speed. Two of her guns were disabled and several armor plates had been loosened. Two of her crew were killed, and more were wounded. One of the wounded was Captain Buchanan, whose left thigh was pierced by a rifle shot.

Meanwhile, the James River Squadron had turned its attention to ''Minnesota'', which had left

Both sides used the respite to prepare for the next day. ''Virginia'' put her wounded ashore and underwent temporary repairs. Captain Buchanan was among the wounded, so command on the second day fell to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones. Jones proved to be no less aggressive than the man he replaced. While ''Virginia'' was being prepared for renewal of the battle, and while ''Congress'' was still ablaze, ''Monitor'', commanded by Lieutenant John L. Worden, arrived in Hampton Roads. The Union ironclad had been rushed to Hampton Roads in hopes of protecting the Union fleet and preventing ''Virginia'' from threatening Union cities. Captain Worden was informed that his primary task was to protect ''Minnesota'', so ''Monitor'' took up a position near the grounded ''Minnesota'' and waited. "All on board felt we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial," wrote Captain Gershom Jacques Van Brunt, ''Minnesota''s commander, in his official report the day after the engagement.

The next morning, at dawn on March 9, 1862, ''Virginia'' left her anchorage at Sewell's Point and moved to attack ''Minnesota'', still aground. She was followed by the three ships of the James River Squadron. They found their course blocked, however, by the newly arrived ''Monitor''. At first, Jones believed the strange craft—which one Confederate sailor mocked as "a cheese on a raft"—to be a boiler being towed from the ''Minnesota'', not realizing the nature of his opponent. Soon, however, it was apparent that he had no choice but to fight her. The first shot of the engagement was fired at ''Monitor'' by ''Virginia''. The shot flew past ''Monitor'' and struck ''Minnesota'', which answered with a broadside; this began what would be a lengthy engagement. "Again, all hands were called to quarters, and when she approached within a mile of us I opened upon her with my stern guns and made a signal to the ''Monitor'' to attack the enemy," Van Brunt added.

Both sides used the respite to prepare for the next day. ''Virginia'' put her wounded ashore and underwent temporary repairs. Captain Buchanan was among the wounded, so command on the second day fell to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones. Jones proved to be no less aggressive than the man he replaced. While ''Virginia'' was being prepared for renewal of the battle, and while ''Congress'' was still ablaze, ''Monitor'', commanded by Lieutenant John L. Worden, arrived in Hampton Roads. The Union ironclad had been rushed to Hampton Roads in hopes of protecting the Union fleet and preventing ''Virginia'' from threatening Union cities. Captain Worden was informed that his primary task was to protect ''Minnesota'', so ''Monitor'' took up a position near the grounded ''Minnesota'' and waited. "All on board felt we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial," wrote Captain Gershom Jacques Van Brunt, ''Minnesota''s commander, in his official report the day after the engagement.

The next morning, at dawn on March 9, 1862, ''Virginia'' left her anchorage at Sewell's Point and moved to attack ''Minnesota'', still aground. She was followed by the three ships of the James River Squadron. They found their course blocked, however, by the newly arrived ''Monitor''. At first, Jones believed the strange craft—which one Confederate sailor mocked as "a cheese on a raft"—to be a boiler being towed from the ''Minnesota'', not realizing the nature of his opponent. Soon, however, it was apparent that he had no choice but to fight her. The first shot of the engagement was fired at ''Monitor'' by ''Virginia''. The shot flew past ''Monitor'' and struck ''Minnesota'', which answered with a broadside; this began what would be a lengthy engagement. "Again, all hands were called to quarters, and when she approached within a mile of us I opened upon her with my stern guns and made a signal to the ''Monitor'' to attack the enemy," Van Brunt added.

After fighting for hours, mostly at close range, neither could overcome the other. The armor of both ships proved adequate. In part, this was because each was handicapped in her offensive capabilities. Buchanan, in ''Virginia'', had not expected to fight another armored vessel, so his guns were supplied only with shell rather than armor-piercing shot. ''Monitor''s guns were used with the standard service charge of only of powder, which did not give the projectile sufficient momentum to penetrate her opponent's armor. Tests conducted after the battle showed that the

After fighting for hours, mostly at close range, neither could overcome the other. The armor of both ships proved adequate. In part, this was because each was handicapped in her offensive capabilities. Buchanan, in ''Virginia'', had not expected to fight another armored vessel, so his guns were supplied only with shell rather than armor-piercing shot. ''Monitor''s guns were used with the standard service charge of only of powder, which did not give the projectile sufficient momentum to penetrate her opponent's armor. Tests conducted after the battle showed that the  Confederate Secretary of the Navy

Confederate Secretary of the Navy

The end came first for ''Virginia''. Because the blockade was unbroken, Norfolk was of little strategic use to the Confederacy, and preliminary plans were laid to move the ship up the James River to the vicinity of Norfolk. Before adequate preparations could be made, the Confederate Army under Major General Benjamin Huger abandoned the city on May 9, without consulting anyone from the Navy. ''Virginia''s draft was too great to permit her to pass up the river, which had a depth of only , and then only under favorable circumstances. She was trapped and could only be captured or sunk by the Union Navy. Rather than allow either, Tatnall decided to destroy his own ship. He had her towed down to Craney Island in Portsmouth, where the gang were taken ashore, and then she was set afire. She burned through the rest of the day and most of the following night; shortly before dawn, the flames reached her magazine, and she blew up.

The end came first for ''Virginia''. Because the blockade was unbroken, Norfolk was of little strategic use to the Confederacy, and preliminary plans were laid to move the ship up the James River to the vicinity of Norfolk. Before adequate preparations could be made, the Confederate Army under Major General Benjamin Huger abandoned the city on May 9, without consulting anyone from the Navy. ''Virginia''s draft was too great to permit her to pass up the river, which had a depth of only , and then only under favorable circumstances. She was trapped and could only be captured or sunk by the Union Navy. Rather than allow either, Tatnall decided to destroy his own ship. He had her towed down to Craney Island in Portsmouth, where the gang were taken ashore, and then she was set afire. She burned through the rest of the day and most of the following night; shortly before dawn, the flames reached her magazine, and she blew up.

''Monitor'' likewise did not survive the year. She was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina, on Christmas Day, to take part in the blockade there. While she was being towed down the coast (under command of her fourth captain, Commander John P. Bankhead), the wind increased and with it the waves; with no high sides, the ''Monitor'' took on water. Soon the water in the hold gained on the pumps, and then put out the fires in her engines. The order was given to abandon ship; most men were rescued by , but 16 went down with her when she sank in the early hours of December 31, 1862.

''Monitor'' likewise did not survive the year. She was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina, on Christmas Day, to take part in the blockade there. While she was being towed down the coast (under command of her fourth captain, Commander John P. Bankhead), the wind increased and with it the waves; with no high sides, the ''Monitor'' took on water. Soon the water in the hold gained on the pumps, and then put out the fires in her engines. The order was given to abandon ship; most men were rescued by , but 16 went down with her when she sank in the early hours of December 31, 1862.

The vulnerability of wooden hulls to armored ships was noted particularly in Britain and France, where the wisdom of the planned conversion of the battle fleet to armor was given a powerful demonstration. Another feature that was emulated was not so successful. Impressed by the ease with which ''Virginia'' had sunk ''Cumberland'', naval architects began to incorporate

The vulnerability of wooden hulls to armored ships was noted particularly in Britain and France, where the wisdom of the planned conversion of the battle fleet to armor was given a powerful demonstration. Another feature that was emulated was not so successful. Impressed by the ease with which ''Virginia'' had sunk ''Cumberland'', naval architects began to incorporate

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

It was fought over two days, March 8–9, 1862, in Hampton Roads, a roadstead in Virginia where the Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

and Nansemond rivers meet the James River just before it enters Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

adjacent to the city of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

. The battle was a part of the effort of the Confederacy to break the Union blockade, which had cut off Virginia's largest cities and major industrial centers, Norfolk and Richmond, from international trade.Musicant 1995, pp. 134–178; Anderson 1962, pp. 71–77; Tucker 2006, p. 151.

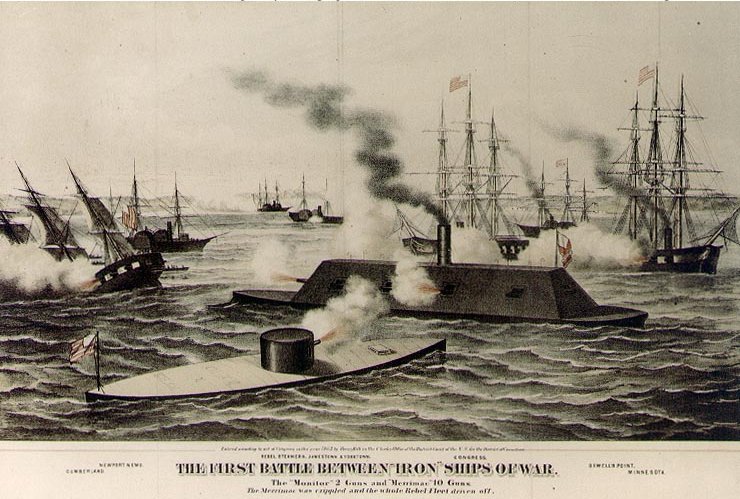

This battle has major significance because it was the first meeting in combat of ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

s, and . The Confederate fleet consisted of the ironclad ram ''Virginia'' (built from the remnants of the burned steam frigate , newest warship for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

/ Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

) and several supporting vessels. On the first day of battle, they were opposed by several conventional, wooden-hulled ships of the Union Navy.

On that day, ''Virginia'' was able to destroy two ships of the federal flotilla, and , and was about to attack a third, , which had run aground. However, the action was halted by darkness and falling tide, so ''Virginia'' retired to take care of her few wounded—which included her captain, Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan—and repair her minimal battle damage.

Determined to complete the destruction of ''Minnesota'', Catesby ap Roger Jones, acting as captain in Buchanan's absence, returned the ship to the fray the next morning, March 9. During the night, however, the ironclad ''Monitor'' had arrived and had taken a position to defend ''Minnesota''. When ''Virginia'' approached, ''Monitor'' intercepted her. The two ironclads fought for about three hours, with neither being able to inflict significant damage on the other. The duel ended indecisively, ''Virginia'' returning to her home at the Gosport Navy Yard for repairs and strengthening, and ''Monitor'' to her station defending ''Minnesota''. The ships did not fight again, and the blockade remained in place.

The battle received worldwide attention, and it had immediate effects on navies around the world. The preeminent naval powers, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, halted further construction of wooden-hulled ships, and others followed suit. Although Britain and France had been engaged in an iron-clad arms race since the 1830s, the Battle of Hampton Roads signaled a new age of naval warfare had arrived for the whole world.Deogracias, Alan J. "The Battle of Hampton Roads: A Revolution in Military Affairs.” U.S. Army Command, 6 June 2003.

A new type of warship, monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

, was produced on the principle of the original. The use of a small number of very heavy guns, mounted so that they could fire in all directions, was first demonstrated by ''Monitor'' but soon became standard in warships of all types. Shipbuilders also incorporated rams into the designs of warship hulls for the rest of the century.

Background

Military situation

The blockade at Norfolk

On April 19, 1861, shortly after the outbreak of hostilities at

On April 19, 1861, shortly after the outbreak of hostilities at Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston ...

, US President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

proclaimed a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

of ports in the seceded states. On April 27, after Virginia and North Carolina had also passed ordinances of secession, the blockade was extended to include their ports also. Even before the extension, local troops seized the Norfolk area and threatened the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth. The commandant there, Captain Charles S. McCauley, though loyal to the Union, was immobilized by advice he received from his subordinate officers, most of whom were in favor of secession. Although he had orders from (Union) Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

to move his ships to Northern ports, he refused to act until April 20, when he gave orders to scuttle the ships in the yard and destroy its facilities.

At least nine ships were burned, among them the screw frigate . One (the old frigate ) was towed away successfully. ''Merrimack'' burned only to the waterline, however, and her engines were more or less intact. The destruction of the navy yard was mostly ineffective; in particular, the large drydock there was relatively undamaged and soon could be restored. Without firing a shot, the advocates of secession had gained for the South its largest navy yard, as well as the hull and engines of what would be in time its most famous warship. They had also seized more than a thousand heavy guns, plus gun carriages and large quantities of gunpowder.

With Norfolk and its navy yard in Portsmouth, the Confederacy controlled the southern side of Hampton Roads. To prevent Union warships from attacking the yard, the Confederates set up batteries at Sewell's Point and Craney Island, at the juncture of the Elizabeth River with the James. (See map.) The Union retained possession of Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

, at Old Point Comfort

Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in the United States. It was renamed ...

on the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the n ...

. They also held a small man-made island known as the Rip Raps

Rip Raps is a small 15 acre (60,000 m²) artificial island at the mouth of the harbor area known as Hampton Roads in the independent city of Hampton in southeastern Virginia in the United States. Its name is derived from the Rip Rap Shoals in Hampt ...

, on the far side of the channel opposite Fort Monroe, and on this island they completed another fort, named Fort Wool

Fort Wool is a decommissioned island fortification located in the mouth of Hampton Roads, adjacent to the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT). Now officially known as Rip Raps Island, the fort has an elevation of 7 feet and sits near Old Point ...

. With Fort Monroe went control of the lower Peninsula as far as Newport News

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

.

Forts Monroe and Wool gave the Union forces control of the entrance to Hampton Roads. The blockade, initiated on April 30, 1861, cut off Norfolk and Richmond from the sea almost completely. To further the blockade, the Union Navy stationed some of its most powerful warships in the roadstead. There, they were under the shelter of the shore-based guns of Fort Monroe and the batteries at Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

* Hampton, Victoria

Canada

* Hampton, New Brunswick

*Ha ...

and Newport News and out of the range of the guns at Sewell's Point and Craney Island. For most of the first year of the war, the Confederacy could do little to oppose or dislodge them.

Birth of the ironclads

When steam propulsion began to be applied to warships, naval constructors renewed their interest in armor for their vessels. Experiments had been tried with armor during theCrimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

(1853–1856), just prior to the American Civil War, and the British and French navies had each built armored ships and were planning to build others. In 1860 the French Navy commissioned , the world's first ocean-going ironclad warship. Great Britain followed a year later with , the world's first armor-plated iron-hulled warship. The use of armor remained controversial, however, and the United States Navy was generally reluctant to embrace the new technology.

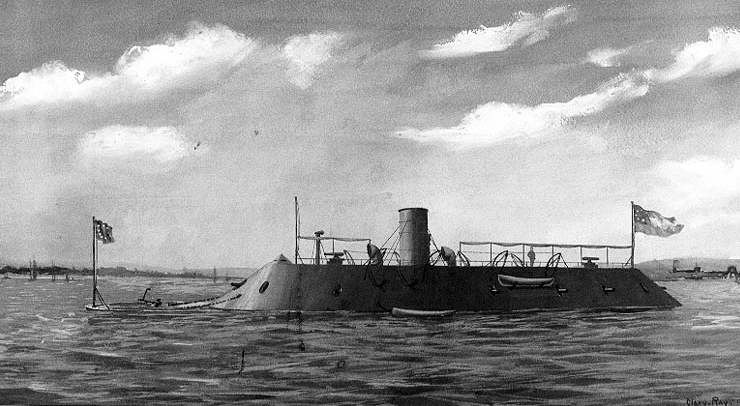

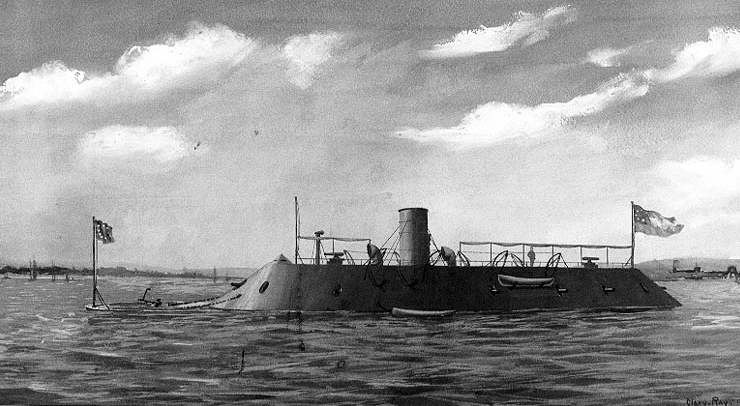

CSS ''Virginia''

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Confederate

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Confederate Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Stephen R. Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was a Democratic senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War. For much of that period, he was chairman of the Committee on Na ...

was an early enthusiast for the advantages of armor. As he looked upon it, the Confederacy could not match the industrial North in numbers of ships at sea, so they would have to compete by building vessels that individually outclassed those of the Union. Armor would provide the edge. Mallory gathered about himself a group of men who could put his vision into practice, among them John M. Brooke, John L. Porter, and William P. Williamson

William Price Williamson (August 10, 1884 – August 17, 1918) was an officer in the United States Navy.

Biography

William Price Williamson was born in Norfolk, Virginia on August 10, 1884, the son of Thom and Julia ''Price'' Williamson. He gr ...

.

When Mallory's men searched the South for factories that could build engines to drive the heavy ships that he wanted, they found no place to do it immediately. At the best facility, the Tredegar Iron Works

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

Tredegar supplied about half the artillery used ...

in Richmond, building engines from scratch would take at least a year. Upon learning this, Williamson suggested taking the engines from the hulk of ''Merrimack'', recently raised from the bed of the Elizabeth River. His colleagues promptly accepted his suggestion and expanded it, proposing that the design of their projected ironclad be adapted to the hull. Porter produced the revised plans, which were submitted to Mallory for approval.

On July 11, 1861, the new design was accepted, and work began almost immediately. The burned-out hull was towed into the graving dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

that the Union Navy had failed to destroy. During the subsequent conversion process, the plans developed further, incorporating an iron ram fitted to the prow. The re-modeled ship's offense, in addition to the ram, consisted of 10 guns: six smooth-bore Dahlgrens, two and two Brooke rifle

The Brooke rifle was a type of rifled, muzzle-loading naval and coast defense gun designed by John Mercer Brooke, an officer in the Confederate States Navy. They were produced by plants in Richmond, Virginia, and Selma, Alabama, between 1861 and ...

s. Trials showed that these rifles firing solid shot would pierce up to eight inches of armor plating.

The Tredegar Iron works could produce both solid shot and shell, and since it was believed that ''Virginia'' would face only wooden ships, she was given only the explosive shell.Nelson, ''Reign of Iron'', 2004 The armor plating, originally meant to be thick, was replaced by double plates, each thick, backed by of iron and pine. The armor was pierced for 14 gunports: four on each broadside, three forward, and three aft. The revisions, together with the usual problems associated with the transportation system of the South, resulted in delays that pushed out the launch date until February 3, 1862, and she was not commissioned until February 17, bearing the name .

USS ''Monitor''

Intelligence that the Confederates were working to develop an ironclad caused consternation for the Union, but Secretary of the Navy

Intelligence that the Confederates were working to develop an ironclad caused consternation for the Union, but Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

waited for Congress to meet to request permission to consider building armored vessels; Congress gave this permission on August 3, 1861. Welles appointed a commission, which became known as the Ironclad Board

The ''Ironclad Board'' was an advisory board established by the Union in 1861 in response to the construction of the ''CSS Virginia'' by the Confederacy during the US Civil War. The primary goal of the Ironclad Board was to develop more battle-wo ...

, of three senior naval officers to choose among the designs that were submitted for consideration. The three men were Captains Joseph Smith, Hiram Paulding, and Commander Charles Henry Davis

Charles Henry Davis ( – ) was an American rear admiral of the United States Navy. While working for the U.S. Coast Survey, he researched tides and currents, and located an uncharted shoal that had caused wrecks off of the coast of New Yor ...

. The board considered seventeen designs, and chose to support three. The first of the three to be completed, even though she was by far the most radical in design, was Swedish engineer and inventor John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive ''Novelty'', which co ...

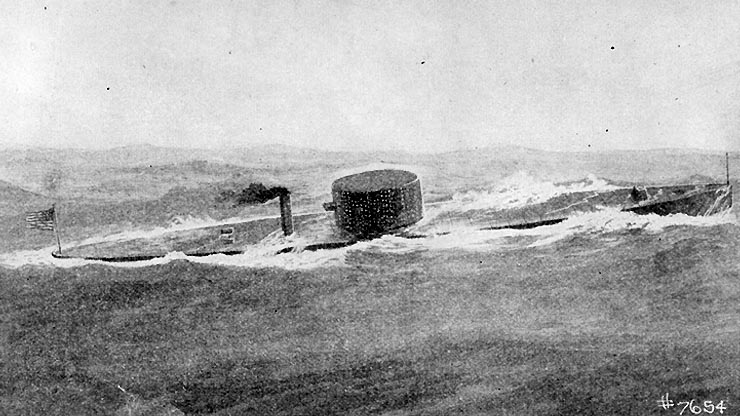

's .

Ericsson's ''Monitor'', which was built at Ericsson's yard on the East River in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, incorporated new and striking design features, the most significant of which were her armor and armament. Instead of the large numbers of guns of rather small bore that had characterized warships in the past, Ericsson opted for only two guns of large caliber; he wanted to use guns, but had to settle for Dahlgren guns when the larger size were unavailable. These were mounted in a cylindrical turret, in diameter, high, covered with iron thick. The whole rotated on a central spindle, and was moved by a steam engine that could be controlled by one man. Ericsson was afraid that using the full 30 pounds of black powder to fire the huge cannon would raise the risk of an explosion in the turret. He demanded that a charge of 15 pounds be used to lessen this possibility.

As with ''Virginia'', trials found that a full charge would pierce armor plate, a finding that would have affected the outcome of the battle. A serious flaw in the design was the pilot house from which the ship would be conned, a small structure forward of the turret on the main deck. Its presence meant that the guns could not fire directly forward, and it was isolated from other activities on the ship. Despite the late start and the novelty of construction, ''Monitor'' was actually completed a few days before her counterpart ''Virginia'', but the Confederates activated ''Virginia'' first.

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

Command

The Confederate chain of command was anomalous.Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Catesby ap Roger Jones had directed much of the conversion of ''Merrimack'' to ''Virginia'', and he was disappointed when he was not named her captain. Jones was retained aboard ''Virginia'', but only as her executive officer. Ordinarily, the ship would have been led by a captain of the Confederate States Navy, to be determined by the rigid seniority system that was in place. Secretary Mallory wanted the aggressive Franklin Buchanan, but at least two other captains had greater seniority and had applied for the post. Mallory evaded the issue by appointing Buchanan, head of the Office of Orders and Detail, flag officer in charge of the defenses of Norfolk and the James River. As such, he could control the movements of ''Virginia''. Technically, therefore, the ship went into the battle without a captain.

On the Union side, command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic ...

was held by Flag Officer

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countries ...

Louis M. Goldsborough

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough (February 18, 1805 – February 20, 1877) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He held several sea commands during the Civil War, including that of the North Atlantic Blockadi ...

. He had devised a plan for his frigates to engage ''Virginia'', hoping to trap her in their crossfire. In the event, his plan broke down completely when four of the ships ran aground (one of them intentionally) in the confined waters of the roadstead. On the day of battle, Goldsborough was absent with the ships cooperating with the Burnside Expedition in North Carolina. In his absence, leadership fell to his second in command, Captain John Marston of . As ''Roanoke'' was one of the ships that ran aground, Marston was unable to materially influence the battle, and his participation is often disregarded. Most accounts emphasize the contribution of the captain of ''Monitor'', John L. Worden

John Lorimer Worden (March 12, 1818 – October 19, 1897) was a U.S. Navy officer in the American Civil War, who took part in the Battle of Hampton Roads, the first-ever engagement between Ironclad warship, ironclad steamships at Hampton Roads, V ...

, to the neglect of others.

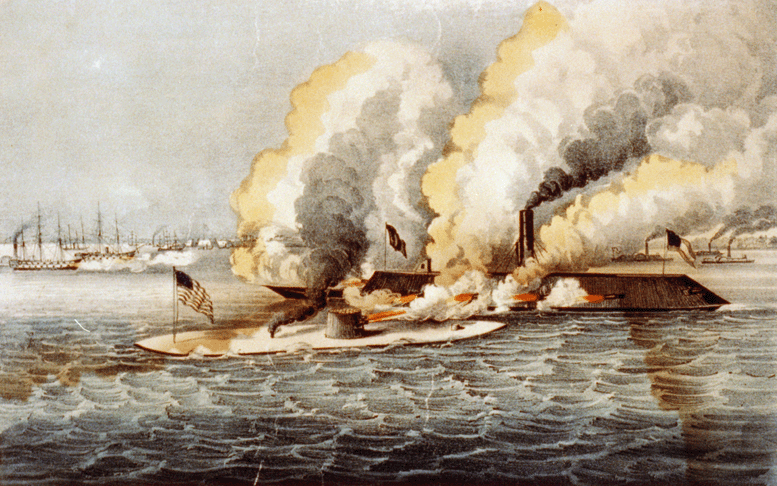

March 8: ''Virginia'' wreaks havoc on wooden Union warships

The battle began when the large and unwieldy CSS ''Virginia'' steamed into Hampton Roads on the morning of March 8, 1862. Captain Buchanan intended to attack as soon as possible. ''Virginia'' was accompanied from her moorings on the Elizabeth River by and , and was joined at Hampton Roads by the James River Squadron, , , and . When they were passing the Union batteries at Newport News, ''Patrick Henry'' was temporarily disabled by a shot in her boiler that killed four of her crew. After repairs, she returned and rejoined the others. At this time, the Union Navy had five warships in the roadstead, in addition to several support vessels. The sloop-of-war and frigate were anchored in the channel near Newport News. The sail frigate and the steam frigates and were near Fort Monroe, along with the storeship . The latter three got under way as soon as they saw ''Virginia'' approaching, but all soon ran aground. ''St. Lawrence'' and ''Roanoke'' took no further important part in the battle.Davis, ''Duel between the first ironclads'', p. 98. ''Virginia'' headed directly for the Union squadron. The battle opened when Union tug ''Zouave'' fired on the advancing enemy, and ''Beaufort'' replied. This preliminary skirmishing had no effect. ''Virginia'' did not open fire until she was within easy range of ''Cumberland''. Return fire from ''Cumberland'' and ''Congress'' bounced off the iron plates without penetrating, although later some of ''Cumberland''s gunfire lightly damaged ''Virginia''. ''Virginia'' rammed ''Cumberland'' below the waterline and she sank rapidly, "gallantly fighting her guns as long as they were above water," according to Buchanan. She took 121 seamen down with her; those wounded brought the casualty total to nearly 150. Ramming ''Cumberland'' nearly resulted in the sinking of ''Virginia'' as well. ''Virginia''s bow ram got stuck in the enemy ship's hull, and as ''Cumberland'' listed and began to go down, she almost pulled ''Virginia'' under with her. At the time the vessels were locked, one of ''Cumberland's'' anchors was hanging directly above the foredeck of ''Virginia''. Had it come loose, the two ships might have gone down together. ''Virginia'' broke free, however, her ram breaking off as she backed away. Buchanan next turned ''Virginia'' on ''Congress''. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith, captain of ''Congress'', ordered his ship grounded in shallow water. By this time, the James River Squadron, commanded by John Randolph Tucker, had arrived and joined ''Virginia'' in the attack on ''Congress''. After an hour of unequal combat, the badly damaged ''Congress'' surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. In retaliation, Buchanan ordered ''Congress'' fired upon with hot shot, cannonballs heated red-hot. ''Congress'' caught fire and burned throughout the rest of the day. Near midnight, the flames reached her magazine and she exploded and sank, stern first. Personnel losses included 110 killed or missing and presumed drowned. Another 26 were wounded, of whom ten died within days.

Although she had not suffered anything like the damage she had inflicted, ''Virginia'' was not completely unscathed. Shots from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and Union troops ashore had riddled her smokestack, reducing her already low speed. Two of her guns were disabled and several armor plates had been loosened. Two of her crew were killed, and more were wounded. One of the wounded was Captain Buchanan, whose left thigh was pierced by a rifle shot.

Meanwhile, the James River Squadron had turned its attention to ''Minnesota'', which had left

Buchanan next turned ''Virginia'' on ''Congress''. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith, captain of ''Congress'', ordered his ship grounded in shallow water. By this time, the James River Squadron, commanded by John Randolph Tucker, had arrived and joined ''Virginia'' in the attack on ''Congress''. After an hour of unequal combat, the badly damaged ''Congress'' surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. In retaliation, Buchanan ordered ''Congress'' fired upon with hot shot, cannonballs heated red-hot. ''Congress'' caught fire and burned throughout the rest of the day. Near midnight, the flames reached her magazine and she exploded and sank, stern first. Personnel losses included 110 killed or missing and presumed drowned. Another 26 were wounded, of whom ten died within days.

Although she had not suffered anything like the damage she had inflicted, ''Virginia'' was not completely unscathed. Shots from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and Union troops ashore had riddled her smokestack, reducing her already low speed. Two of her guns were disabled and several armor plates had been loosened. Two of her crew were killed, and more were wounded. One of the wounded was Captain Buchanan, whose left thigh was pierced by a rifle shot.

Meanwhile, the James River Squadron had turned its attention to ''Minnesota'', which had left Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

to join in the battle and had run aground. After ''Virginia'' had dealt with the surrender of ''Congress'', she joined the James River Squadron despite her damage. Because of her deep draft and the falling tide, however, ''Virginia'' was unable to get close enough to be effective, and darkness prevented the rest of the squadron from aiming their guns to any effect. The attack was therefore suspended. ''Virginia'' left with the expectation of returning the next day and completing the task. She retreated into the safety of Confederate-controlled waters off Sewell's Point for the night, but had killed 250 enemy sailors and had lost two. The Union had lost two ships and three were aground.

The United States Navy's greatest defeat (and would remain so until World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

) caused panic in Washington. As Lincoln's Cabinet met to discuss the disaster, the frightened Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

told the others that ''Virginia'' might attack East coast cities, and even shell the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

before the meeting ended. Welles assured his colleagues that they were safe as the ship could not traverse the Potomac River. He added that the Union also had an ironclad, and that it was heading to meet ''Virginia''.

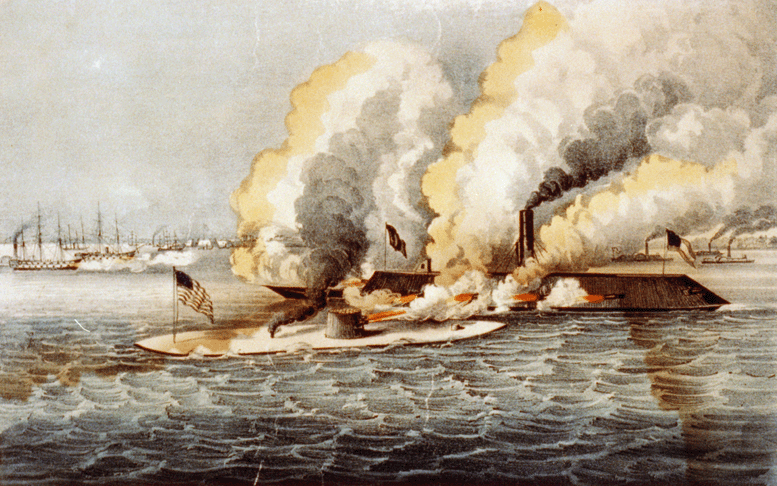

March 9: ''Monitor'' engages ''Virginia''

Both sides used the respite to prepare for the next day. ''Virginia'' put her wounded ashore and underwent temporary repairs. Captain Buchanan was among the wounded, so command on the second day fell to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones. Jones proved to be no less aggressive than the man he replaced. While ''Virginia'' was being prepared for renewal of the battle, and while ''Congress'' was still ablaze, ''Monitor'', commanded by Lieutenant John L. Worden, arrived in Hampton Roads. The Union ironclad had been rushed to Hampton Roads in hopes of protecting the Union fleet and preventing ''Virginia'' from threatening Union cities. Captain Worden was informed that his primary task was to protect ''Minnesota'', so ''Monitor'' took up a position near the grounded ''Minnesota'' and waited. "All on board felt we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial," wrote Captain Gershom Jacques Van Brunt, ''Minnesota''s commander, in his official report the day after the engagement.

The next morning, at dawn on March 9, 1862, ''Virginia'' left her anchorage at Sewell's Point and moved to attack ''Minnesota'', still aground. She was followed by the three ships of the James River Squadron. They found their course blocked, however, by the newly arrived ''Monitor''. At first, Jones believed the strange craft—which one Confederate sailor mocked as "a cheese on a raft"—to be a boiler being towed from the ''Minnesota'', not realizing the nature of his opponent. Soon, however, it was apparent that he had no choice but to fight her. The first shot of the engagement was fired at ''Monitor'' by ''Virginia''. The shot flew past ''Monitor'' and struck ''Minnesota'', which answered with a broadside; this began what would be a lengthy engagement. "Again, all hands were called to quarters, and when she approached within a mile of us I opened upon her with my stern guns and made a signal to the ''Monitor'' to attack the enemy," Van Brunt added.

Both sides used the respite to prepare for the next day. ''Virginia'' put her wounded ashore and underwent temporary repairs. Captain Buchanan was among the wounded, so command on the second day fell to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones. Jones proved to be no less aggressive than the man he replaced. While ''Virginia'' was being prepared for renewal of the battle, and while ''Congress'' was still ablaze, ''Monitor'', commanded by Lieutenant John L. Worden, arrived in Hampton Roads. The Union ironclad had been rushed to Hampton Roads in hopes of protecting the Union fleet and preventing ''Virginia'' from threatening Union cities. Captain Worden was informed that his primary task was to protect ''Minnesota'', so ''Monitor'' took up a position near the grounded ''Minnesota'' and waited. "All on board felt we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial," wrote Captain Gershom Jacques Van Brunt, ''Minnesota''s commander, in his official report the day after the engagement.

The next morning, at dawn on March 9, 1862, ''Virginia'' left her anchorage at Sewell's Point and moved to attack ''Minnesota'', still aground. She was followed by the three ships of the James River Squadron. They found their course blocked, however, by the newly arrived ''Monitor''. At first, Jones believed the strange craft—which one Confederate sailor mocked as "a cheese on a raft"—to be a boiler being towed from the ''Minnesota'', not realizing the nature of his opponent. Soon, however, it was apparent that he had no choice but to fight her. The first shot of the engagement was fired at ''Monitor'' by ''Virginia''. The shot flew past ''Monitor'' and struck ''Minnesota'', which answered with a broadside; this began what would be a lengthy engagement. "Again, all hands were called to quarters, and when she approached within a mile of us I opened upon her with my stern guns and made a signal to the ''Monitor'' to attack the enemy," Van Brunt added.

After fighting for hours, mostly at close range, neither could overcome the other. The armor of both ships proved adequate. In part, this was because each was handicapped in her offensive capabilities. Buchanan, in ''Virginia'', had not expected to fight another armored vessel, so his guns were supplied only with shell rather than armor-piercing shot. ''Monitor''s guns were used with the standard service charge of only of powder, which did not give the projectile sufficient momentum to penetrate her opponent's armor. Tests conducted after the battle showed that the

After fighting for hours, mostly at close range, neither could overcome the other. The armor of both ships proved adequate. In part, this was because each was handicapped in her offensive capabilities. Buchanan, in ''Virginia'', had not expected to fight another armored vessel, so his guns were supplied only with shell rather than armor-piercing shot. ''Monitor''s guns were used with the standard service charge of only of powder, which did not give the projectile sufficient momentum to penetrate her opponent's armor. Tests conducted after the battle showed that the Dahlgren gun

Dahlgren guns were muzzle-loading naval artillery designed by Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren USN (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870), mostly used in the period of the American Civil War. Dahlgren's design philosophy evolved from an accidental e ...

s could be operated safely and efficiently with charges of as much as . However, despite this, as the two Ironclads circled each other during the fight, the ''Monitor'' was about to penetrate the ''Virginia''’s armor, but a misfiring of its weapons caused it to lose the advantage. At 10 AM that morning, the ''Virginia'' grounded. The ''Monitor'' opened fire on its vulnerable adversary, yet the ''Virginia'' was able to scrape off the shore and rejoin the fight.

Later during the battle, Acting Master Louis N. Stodder and officers Stimers and Truscott were inside the gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

, discussing the course of action. Stodder was leaning against the turret's inside wall when it took a direct hit. Holzer, 2013, p. 13 Stodder was knocked unconscious and taken below, where it took him an hour to regain consciousness. Stodder thus became the first man injured during the battle. He was replaced by Stimers.

The battle finally ceased when a shell from ''Virginia'' struck the pilot house of ''Monitor'' and exploded, driving fragments of paint and iron through the viewing slits into Worden's eyes and temporarily blinding him. As no one else could see to command the ship, ''Monitor'' was forced to draw off. The executive officer, Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene, took over, and ''Monitor'' returned to the fight. In the period of command confusion, however, the crew of ''Virginia'' believed that their opponent had withdrawn. Although ''Minnesota'' was still aground, the falling tide meant that she was out of reach. Furthermore, ''Virginia'' had suffered enough damage to require extensive repair. Convinced that his ship had won the day, Jones ordered her back to Norfolk. At about this time, ''Monitor'' returned, only to discover her opponent apparently giving up the fight. Convinced that ''Virginia'' was quitting, with orders only to protect ''Minnesota'' and not to risk his ship unnecessarily, Greene did not pursue. Thus, each side misinterpreted the moves of the other, and as a result each claimed victory.

Confederate Secretary of the Navy

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was a Democratic senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War. For much of that period, he was chairman of the Committee on Nav ...

wrote to Confederate President Davis of the action:

The conduct of the Officers and men of the squadron … reflects unfading honor upon themselves and upon the Navy. The report will be read with deep interest, and its details will not fail to rouse the ardor and nerve the arms of our gallant seamen. It will be remembered that the ''Virginia'' was a novelty in naval architecture, wholly unlike any ship that ever floated; that her heaviest guns were equal novelties in ordnance; that her motive power and obedience to her helm were untried, and her officers and crew strangers, comparatively, to the ship and to each other; and yet, under all these disadvantages, the dashing courage and consummate professional ability of Flag Officer Buchanan and his associates achieved the most remarkable victory which naval annals record.In Washington, belief that ''Monitor'' had vanquished ''Virginia'' was so strong that Worden and his men were awarded the thanks of Congress:

Resolved . . . That the thanks of Congress and the American people are due and are hereby tendered to Lieutenant J. L. Worden, of the United States Navy, and to the officers and men of the ironclad gunboat ''Monitor'', under his command, for the skill and gallantry exhibited by them in the remarkable battle between the ''Monitor'' and the rebel ironclad steamer ''Merrimack''.During the two-day engagement, USS ''Minnesota'' shot off 78 rounds of 10-inch solid shot; 67 rounds of 10-inch shells with 15-second fuse; 169 rounds of 9-inch solid shot; 180 9-inch shells with 15-second fuse; 35 8-inch shells with 15-second fuse and 5,567.5 pounds of service powder. Three crew members, Alexander Winslow, Henry Smith and Dennis Harrington were killed during the battle and 16 were wounded. One of ''Monitor''s crew, Quartermaster Peter Williams, was awarded the

Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

for his actions during the battle.

Spring 1862—a standoff at Hampton Roads

''Virginia'' remained in drydock for almost a month, getting repairs for battle damage as well as minor modifications to improve her performance. On April 4, she was able to leave drydock. Buchanan, still recovering from his wound, had hoped that Catesby Jones would be picked to succeed him, and most observers believed that Jones's performance during the battle was outstanding. Theseniority

Seniority is the state of being older or placed in a higher position of status relative to another individual, group, or organization. For example, one employee may be senior to another either by role or rank (such as a CEO vice a manager), or by ...

system for promotion in the Navy scuttled his chances, however, and the post went to the 67-year-old Commodore Josiah Tattnall III

Commodore Josiah Tattnall (November 9, 1795 – June 14, 1871) was an officer in the United States Navy during the War of 1812, the Second Barbary War and the Mexican–American War. He later served in the Confederate Navy during the American C ...

. ''Monitor'', not severely damaged, remained on duty. Like his antagonist Jones, Greene was deemed too young to remain as captain; the day after the battle, he was replaced with Lieutenant Thomas Oliver Selfridge Jr. Two days later, Selfridge was in turn relieved by Lieutenant William Nicholson Jeffers.

By late March, the Union blockade fleet had been augmented by hastily refitted civilian ships, including the powerful SS ''Vanderbilt'', , SS ''Illinois'', and SS ''Ericsson''. These had been outfitted with rams and some iron plating. By late April, the new ironclads USRC ''E. A. Stevens'' and had also joined the blockade.

Each side considered how best to eliminate the threat posed by its opponent, and after ''Virginia'' returned each side tried to goad the other into attacking under unfavorable circumstances. Both captains declined the opportunity to fight in waters not of their own choosing; Jeffers in particular was under positive orders not to risk his ship. Consequently, each vessel spent the next month in what amounted to posturing. Not only did the two ships not fight each other, neither ship ever fought again after March 9.

Destruction of the combatants

The end came first for ''Virginia''. Because the blockade was unbroken, Norfolk was of little strategic use to the Confederacy, and preliminary plans were laid to move the ship up the James River to the vicinity of Norfolk. Before adequate preparations could be made, the Confederate Army under Major General Benjamin Huger abandoned the city on May 9, without consulting anyone from the Navy. ''Virginia''s draft was too great to permit her to pass up the river, which had a depth of only , and then only under favorable circumstances. She was trapped and could only be captured or sunk by the Union Navy. Rather than allow either, Tatnall decided to destroy his own ship. He had her towed down to Craney Island in Portsmouth, where the gang were taken ashore, and then she was set afire. She burned through the rest of the day and most of the following night; shortly before dawn, the flames reached her magazine, and she blew up.

The end came first for ''Virginia''. Because the blockade was unbroken, Norfolk was of little strategic use to the Confederacy, and preliminary plans were laid to move the ship up the James River to the vicinity of Norfolk. Before adequate preparations could be made, the Confederate Army under Major General Benjamin Huger abandoned the city on May 9, without consulting anyone from the Navy. ''Virginia''s draft was too great to permit her to pass up the river, which had a depth of only , and then only under favorable circumstances. She was trapped and could only be captured or sunk by the Union Navy. Rather than allow either, Tatnall decided to destroy his own ship. He had her towed down to Craney Island in Portsmouth, where the gang were taken ashore, and then she was set afire. She burned through the rest of the day and most of the following night; shortly before dawn, the flames reached her magazine, and she blew up.

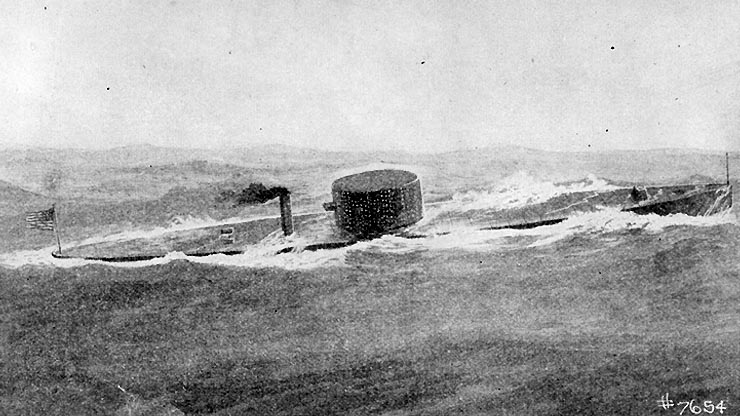

''Monitor'' likewise did not survive the year. She was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina, on Christmas Day, to take part in the blockade there. While she was being towed down the coast (under command of her fourth captain, Commander John P. Bankhead), the wind increased and with it the waves; with no high sides, the ''Monitor'' took on water. Soon the water in the hold gained on the pumps, and then put out the fires in her engines. The order was given to abandon ship; most men were rescued by , but 16 went down with her when she sank in the early hours of December 31, 1862.

''Monitor'' likewise did not survive the year. She was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina, on Christmas Day, to take part in the blockade there. While she was being towed down the coast (under command of her fourth captain, Commander John P. Bankhead), the wind increased and with it the waves; with no high sides, the ''Monitor'' took on water. Soon the water in the hold gained on the pumps, and then put out the fires in her engines. The order was given to abandon ship; most men were rescued by , but 16 went down with her when she sank in the early hours of December 31, 1862.

The victor

The victory claims that were made by each side in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Hampton Roads, as both were based on misinterpretations of the opponent's behavior, have been dismissed by present-day historians. They agree that the result of the ''Monitor''–''Virginia'' encounter was not a victory for either side. As the combat between ironclads was the primary significance of the battle, the general verdict is that the overall result was a draw. All would acknowledge that the Southern fleet inflicted far more damage than it received, which would ordinarily imply that they had gained a tactical victory. Compared to other Civil War battles, the loss of men and ships for the Union Navy would be considered a clear defeat. On the other hand, the blockade was not seriously threatened, so the entire battle can be regarded as an assault that ultimately failed. However, initially after the Battle of Hampton Roads, both the Confederate and Union media claimed victory for their own sides. A headline in a Boston newspaper the day after the battle read "The Merrimac Driven back by the Steamer!", implying a Union victory, while Confederate media focused on their original success against wooden Union ships. Despite the battle ending in a stalemate, it was seen by both sides as an opportunity to raise war-time morale, especially since the ironclad ships were an exciting naval innovation that intrigued citizens. Evaluation of the strategic results is likewise disputed. The blockade was maintained, even strengthened, and ''Virginia'' was bottled up in Hampton Roads. Because a decisive Confederate weapon was negated, some have concluded that the Union could claim a strategic victory. Confederate advocates can counter, however, by arguing that ''Virginia'' had a military significance larger than the blockade, which was only a small part of the war inTidewater Virginia

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Maryl ...

. Her mere presence was sufficient to close the James River to Federal incursions. She also imposed other constraints on the Peninsula Campaign then being mounted by the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

under General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, who worried that she could interfere with his positions on the York River. Although his fears were baseless, they continued to affect the movements of his army until ''Virginia'' was destroyed.

Impact upon naval warfare

Both days of the battle attracted attention from almost all the world's navies. USS ''Monitor'' became the prototype for the monitor warship type. She thus became the first of two ships whose names were applied to entire classes of their successors, the other being . Many more were built, includingriver monitor

River monitors are military craft designed to patrol rivers.

They are normally the largest of all riverine warships in river flotillas, and mount the heaviest weapons. The name originated from the US Navy's , which made her first appearance in ...

s, and they played key roles in Civil War battles on the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and James rivers.

The US immediately started the construction of ten more monitors based on Ericsson's original larger plan, known as the s. More than 20 additional monitors were built by the Union by the end of the war. However, while the design proved exceptionally well-suited for river combat, the low profile and heavy turret caused poor seaworthiness in rough waters. Russia, fearing that the American Civil War would spill into Russian Alaska

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

, launched ten sister ships, as soon as Ericsson's plans reached St. Petersburg. What followed has been described as ''"Monitor mania"''. The revolving turret later inspired similar designs for future warships, which eventually became the modern battleship.

The vulnerability of wooden hulls to armored ships was noted particularly in Britain and France, where the wisdom of the planned conversion of the battle fleet to armor was given a powerful demonstration. Another feature that was emulated was not so successful. Impressed by the ease with which ''Virginia'' had sunk ''Cumberland'', naval architects began to incorporate

The vulnerability of wooden hulls to armored ships was noted particularly in Britain and France, where the wisdom of the planned conversion of the battle fleet to armor was given a powerful demonstration. Another feature that was emulated was not so successful. Impressed by the ease with which ''Virginia'' had sunk ''Cumberland'', naval architects began to incorporate rams

In engineering, RAMS (reliability, availability, maintainability and safety)

''A record of events in Norfolk County, Virginia''

online text with an entire chapter on the battle.

Civil War Naval History

USS ''Monitor'' National Historical Site

* – Its 'revolutionary' gun turret has been raised from the ocean floor.

On-line exhibition of the ''Monitor''

An original 1862 ''Chicago Tribune'' Article

*

* First Edition Report on th

Newspaper coverage of the Battle of Hampton Roads

*

CWSAC Report Update

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hampton Roads 1862 in Virginia Peninsula campaign Battles of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Naval battles of the American Civil War Battles of the American Civil War in Virginia Inconclusive battles of the American Civil War 1862 in the American Civil War Riverine warfare March 1862 events

Commemorating the battle: ''Virginia''

The name of the warship that served the Confederacy in the Battle of Hampton Roads has been a continuing source of confusion and some contention. She was originally a screw frigate in theUnited States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

carrying the name . All parties continued to use the name after her capture by secessionists while she was being rebuilt as an ironclad. When her conversion was almost complete, her name was officially changed to . Despite the official name change, Union accounts persisted in calling ''Merrimack'' by her original name, while Confederate sources used either ''Virginia'' or ''Merrimac(k)''. The alliteration of ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' has persuaded most popular accounts to adopt the familiar name, even when it is acknowledged to be technically incorrect.

A CSS ''Merrimac'' did actually exist. She was a paddle wheel steamer named for the victor (as most Southerners saw it) at Hampton Roads. She was used for running the blockade until she was captured and taken into Federal service, still named ''Merrimac.'' Her name was a spelling variant of the river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of w ...

, namesake of USS ''Merrimack''. Both spellings are still in use around the Hampton Roads area.

A small community in Montgomery County, Virginia

Montgomery County is a county located in the Valley and Ridge area of the U.S. state of Virginia. As population in the area increased, Montgomery County was formed in 1777 from Fincastle County, which in turn had been taken from Botetourt Coun ...

, near the location where the iron for the Confederate ironclad was forged is now known as Merrimac. Some of the iron mined there and used in the plating on the Confederate ironclad is displayed at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. The anchor of ''Virginia'' sits on the lawn in front of the American Civil War Museum

The American Civil War Museum is a multi-site museum in the Greater Richmond Region of central Virginia, dedicated to the history of the American Civil War. The museum operates three sites: The White House of the Confederacy, American Civil War ...

in Richmond.

Commemorating the battle: ''Monitor''

After resting undetected on the ocean floor for 111 years, the wreck of ''Monitor'' was located by a team of scientists in 1973. The remains of the ship were found upside down offCape Hatteras

Cape Hatteras is a cape located at a pronounced bend in Hatteras Island, one of the barrier islands of North Carolina.

Long stretches of beach, sand dunes, marshes, and maritime forests create a unique environment where wind and waves shap ...

, on a relatively flat, sandy bottom at a depth of about . In 1987, the site was declared a National Marine Sanctuary

A U.S. National Marine Sanctuary is a zone within United States waters where the marine environment enjoys special protection. The program began in 1972 in response to public concern about the plight of marine ecosystems.

A U.S. National Marine ...

, the first shipwreck to receive this distinction.

Because of ''Monitor''s advanced state of deterioration, timely recovery of remaining significant artifacts and ship components became critical. Numerous fragile artifacts, including the innovative turret and its two Dahlgren guns, an anchor, steam engine, and propeller, have been recovered. They were transported back to Hampton Roads to the Mariners' Museum

The Mariners' Museum and Park is located in Newport News, Virginia, United States. Designated as America’s ''National Maritime Museum'' by Congress, it is one of the largest maritime museums in North America. The Mariners' Museum Library, cont ...

in Newport News

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, where they were treated in special tanks to stabilize the metal. It is reported that it will take about ten years for the metal to completely stabilize. The new USS ''Monitor'' Center at the Mariners' Museum officially opened on March 9, 2007, and a full-scale copy of USS ''Monitor'', the original recovered turret, and artifacts and related items are now on display.

Commemorating the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads was a significant event in both Naval and Civil War history that has been detailed in many books, televised Civil War documentaries, and in film, to include TNT's 1991 ''Ironclads

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

''. In New York City, where the designer of the Monitor, John Ericsson, died in March 1889, a statue was commissioned by the state to commemorate the battle between the Ironclads. The statue features a stylized male nude allegorical figure on water between two iron cleats. It is located in Msgr McGolrick Park.

In Virginia, the state dedicated the Monitor-Merrimack Overlook at Anderson Park on a jetty that overlooks the site of the battle. The park contains several historical markers commemorating both ships. Also, in 1992, Virginia dedicated the $400 million, 4.6-mile-long Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel, which is located less than 1 mile from the site of the battle.

References in popular culture

* The film '' Hearts in Bondage'' (Republic Pictures, 1936), directed by Lew Ayres, tells the story of the building of USS ''Monitor'' and the following Battle of Hampton Roads. * A 1991 made-for-television movie called ''Ironclads

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

'', produced by TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

, was made about the battle.

* The album '' The Monitor'', the second studio album by New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

band Titus Andronicus

''Titus Andronicus'' is a tragedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1588 and 1593, probably in collaboration with George Peele. It is thought to be Shakespeare's first tragedy and is often seen as his attempt to emul ...

, ends with a fourteen-minute track that references the battle.

* In Canyonlands National Park, Utah, there are two buttes named after ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimac''. There is a viewpoint with a placard describing the significance of their names.

* Sleater-Kinney recorded an indie rock song referencing the battle, "Ironclad," on the album '' All Hands on the Bad One'' in 2000.

* The book ''The Virginia'' by Winston Brady, based on the Battle of Hampton Roads, depicts Captain(s) Franklin Buchanan and John Worden as tragic heroes who are injured during the battle as a punishment for their over-confidence created by the powerful, nigh-indestructible ships they commanded.

* In the novel '' The Claw of the Conciliator'' by Gene Wolfe

Gene Rodman Wolfe (May 7, 1931 – April 14, 2019) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer. He was noted for his dense, allusive prose as well as the strong influence of his Catholic faith. He was a prolific short story writer and nove ...

, set in the Earth's future, the narrator tells a story from a book of myths that conflates the battle with the legend of Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

and the Minotaur.

See also

*List of United States Navy ships

List of United States Navy ships is a comprehensive listing of all ships that have been in service to the United States Navy during the history of that service. The US Navy maintains its official list of ships past and present at the Naval Vessel ...

* List of ships of the Confederate States Navy

This is a list of ships of the Confederate States Navy (CSN), used by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War between 1861 and 1865. Included are some types of civilian vessels, such as blockade runners, steamboats, and pr ...

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

* Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

* Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

Notes

Abbreviations used in these notes: : ORA (Official records, armies): ''War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies.'' : ORN (Official records, navies): ''Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.''References

* * * * * * * (translation by Paolo E. Coletta of ''Marina del Sud: storia della marina confederate nella Guerra Civile Americana, 1861–1865.'' Rizzoli, 1993.) * * * * Quarstein, John V., ''C.S.S. Virginia, Mistress of Hampton Roads'', self-published for the Virginia Civil War Battles and Leaders Series; 2000. * * * * * *External links

''A record of events in Norfolk County, Virginia''

online text with an entire chapter on the battle.

Civil War Naval History

USS ''Monitor'' National Historical Site

* – Its 'revolutionary' gun turret has been raised from the ocean floor.

On-line exhibition of the ''Monitor''

An original 1862 ''Chicago Tribune'' Article

*

* First Edition Report on th

Newspaper coverage of the Battle of Hampton Roads

*

CWSAC Report Update

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hampton Roads 1862 in Virginia Peninsula campaign Battles of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Naval battles of the American Civil War Battles of the American Civil War in Virginia Inconclusive battles of the American Civil War 1862 in the American Civil War Riverine warfare March 1862 events