Axis–Yugoslav Pact on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On 25 March 1941,

After the French armistice in June 1940, only the

After the French armistice in June 1940, only the

On 6 March, the Crown Council was summoned, and Prince Paul informed of Hitler's demand for accession. Cincar-Marković presented the foreign situation and the problems related to Yugoslav accession, and Pešić portrayed the poor military situation. It was generally concluded from the discussions that accession would occur but that certain limitations and reserves were be demanded from Germany, with Cincar-Marković in charge of drafting those points, which would be held in highest secrecy. The conference showed that the question of accession was very serious and, with respect to public opinion, very difficult.

On 6 March, the Crown Council was summoned, and Prince Paul informed of Hitler's demand for accession. Cincar-Marković presented the foreign situation and the problems related to Yugoslav accession, and Pešić portrayed the poor military situation. It was generally concluded from the discussions that accession would occur but that certain limitations and reserves were be demanded from Germany, with Cincar-Marković in charge of drafting those points, which would be held in highest secrecy. The conference showed that the question of accession was very serious and, with respect to public opinion, very difficult. The next day, Cincar-Marković called Viktor von Heeren, the German minister in Belgrade, to the ministry and informed him of the Crown Council had agreed to Hitler's wish for Yugoslav accession to the pact. Simultaneously, an uneasiness, sparked by anti-Yugoslav manifestations and the negative articles in the media in Bulgaria in recent days, came to the fore.

Then, Ribbentrop was asked to clarify through Heeren whether Yugoslavia would receive a written statement from Germany and Italy if it acceded that Yugoslavia's sovereignty and territorial integrity would be respected; that no Yugoslav military aid would be requested and, during the creation of a new order in Europe, that the Yugoslav interest in free access to the Aegean Sea through Thessaloniki would be considered.

Cincar-Marković noted while he presented those points that there had already been a consensus on all questions. He then informed Paul that Ribbentrop had offered written guarantees. To clarify the situation, Cincar-Marković again asked for a precise answer from the German government to confirm those questions, which would help the Yugoslav government to implement the desired policy.

On 8 March, Heeren strictly confidentially contacted the German ministry. He stated that he had a strong impression that Yugoslavia had already decided that it would soon join the pact if the Germans either fulfilled the demands presented by Cincar-Marković or only slightly amended the German-Italian written statements. Heeren believed that Ribbentrop's incentive for another discussion with Paul was very appropriate and would be best held at the Brdo Castle, near Kranj.

In Belgrade's political and military circles, joining the German camp was generally discussed, but the thought that it would come in stages, with the help of government statements, prevailed and that by not acceding the pact would spare the population's hostile mood. The same day that Heeren contacted Ribbentrop about the latter's instructions, Heeren decided to see Cincar-Marković to state immediately that the German-Italian response to all three points had been positive. Heeren then warned Cincar-Marković the situation made it seem that it was in the best interest for Yugoslavia to decide on its accession as fast as possible.

On 9 March, continuing his phone conversation, Ribbentrop stated to Heeren from

The next day, Cincar-Marković called Viktor von Heeren, the German minister in Belgrade, to the ministry and informed him of the Crown Council had agreed to Hitler's wish for Yugoslav accession to the pact. Simultaneously, an uneasiness, sparked by anti-Yugoslav manifestations and the negative articles in the media in Bulgaria in recent days, came to the fore.

Then, Ribbentrop was asked to clarify through Heeren whether Yugoslavia would receive a written statement from Germany and Italy if it acceded that Yugoslavia's sovereignty and territorial integrity would be respected; that no Yugoslav military aid would be requested and, during the creation of a new order in Europe, that the Yugoslav interest in free access to the Aegean Sea through Thessaloniki would be considered.

Cincar-Marković noted while he presented those points that there had already been a consensus on all questions. He then informed Paul that Ribbentrop had offered written guarantees. To clarify the situation, Cincar-Marković again asked for a precise answer from the German government to confirm those questions, which would help the Yugoslav government to implement the desired policy.

On 8 March, Heeren strictly confidentially contacted the German ministry. He stated that he had a strong impression that Yugoslavia had already decided that it would soon join the pact if the Germans either fulfilled the demands presented by Cincar-Marković or only slightly amended the German-Italian written statements. Heeren believed that Ribbentrop's incentive for another discussion with Paul was very appropriate and would be best held at the Brdo Castle, near Kranj.

In Belgrade's political and military circles, joining the German camp was generally discussed, but the thought that it would come in stages, with the help of government statements, prevailed and that by not acceding the pact would spare the population's hostile mood. The same day that Heeren contacted Ribbentrop about the latter's instructions, Heeren decided to see Cincar-Marković to state immediately that the German-Italian response to all three points had been positive. Heeren then warned Cincar-Marković the situation made it seem that it was in the best interest for Yugoslavia to decide on its accession as fast as possible.

On 9 March, continuing his phone conversation, Ribbentrop stated to Heeren from

On 25 March, the pact was signed at the

On 25 March, the pact was signed at the

On March 27, the regime was overthrown in a

On March 27, the regime was overthrown in a

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

signed the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

with the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. The agreement was reached after months of negotiations between Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Yugoslavia and was signed at the Belvedere Belvedere (from Italian, meaning "beautiful sight") may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Belvedere, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

Africa

* Belvedere (Casablanca), a neighborhood in Casablanca, Morocco

*Belvedere, Harare, Zi ...

in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

by Joachim von Ribbentrop, German foreign minister

, insignia = Bundesadler Bundesorgane.svg

, insigniasize = 80px

, insigniacaption =

, department = Federal Foreign Office

, image = Annalena Baerbock (cropped, 2).jpg

, alt =

, incumbent = Annalena Baerbock

, incumbentsince = 8 December ...

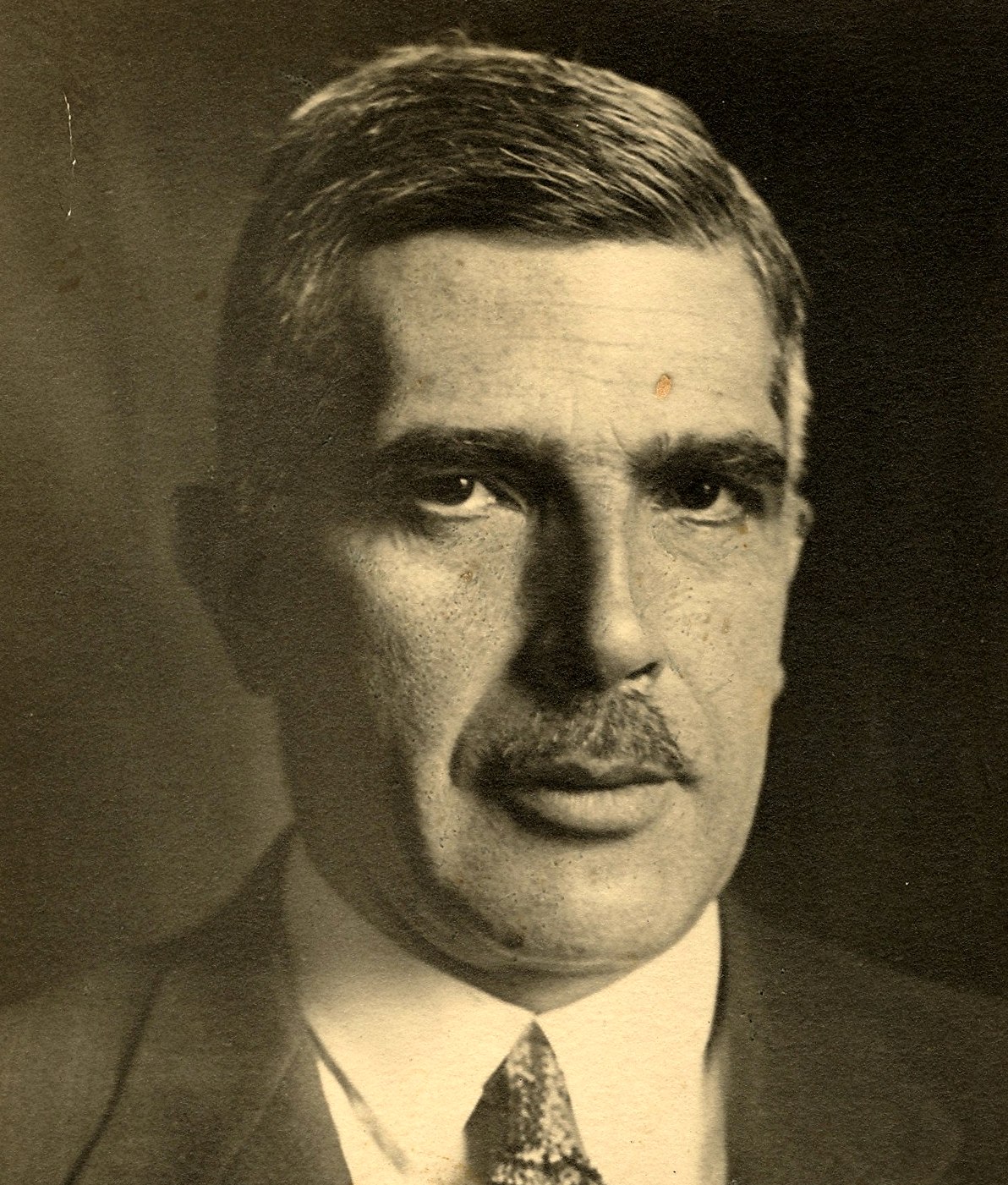

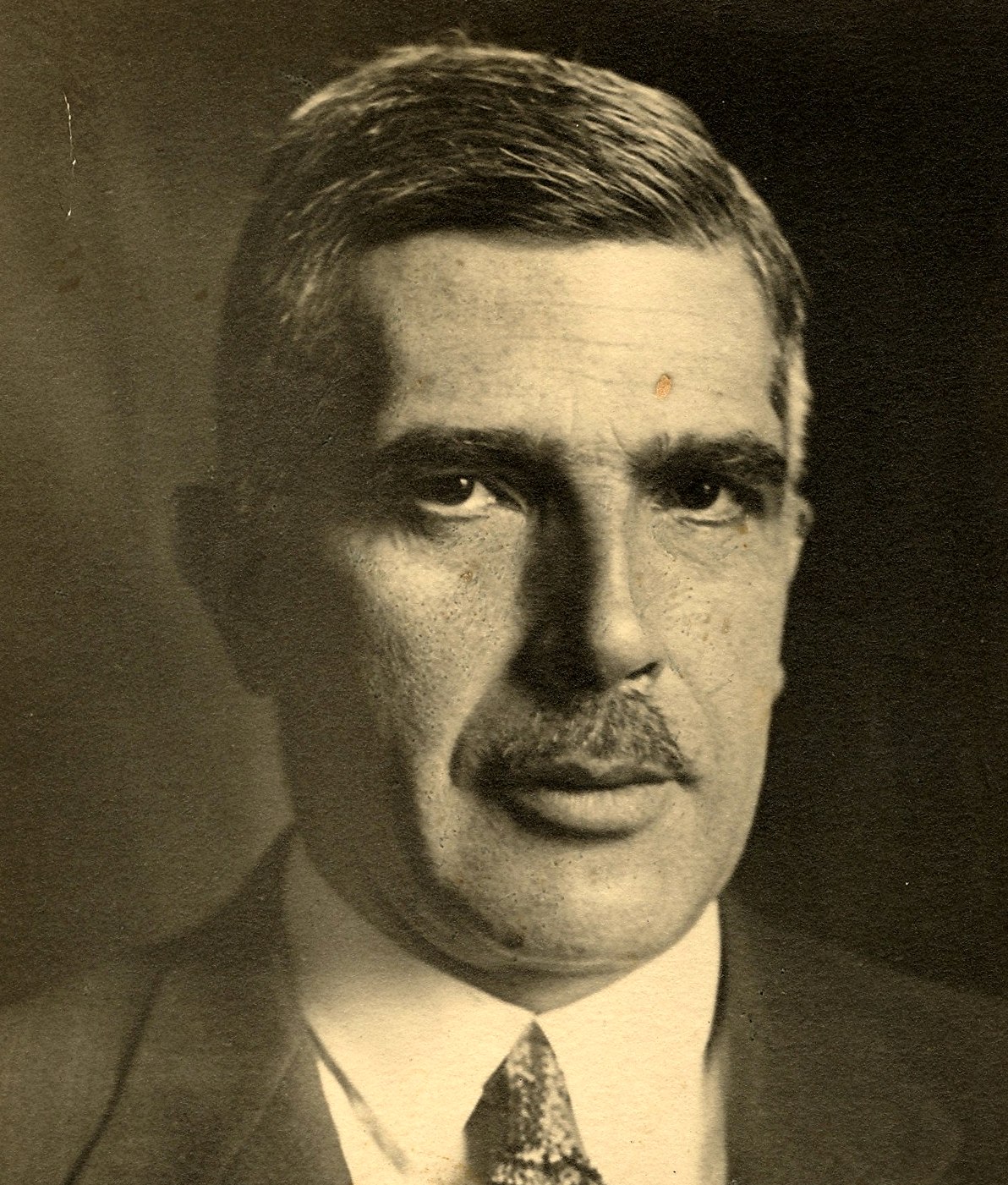

, and Dragiša Cvetković

Dragiša Cvetković ( sr-cyr, Драгиша Цветковић; 15 January 1893 – 18 February 1969) was a Yugoslav politician active in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He served as the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1939 to 1941. ...

, Yugoslav Prime Minister. Pursuant to the alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, the parties agreed that the Axis powers would respect Yugoslav sovereignty and territorial integrity, including the Axis refraining from seeking permission to transport troops through Yugoslavia or requesting any military assistance.

Yugoslav accession to the Tripartite Pact ( sh, Тројни пакт, italic=no / ) was short-lived, however. On 27 March 1941, two days after the agreement had been signed, the Yugoslav government was overthrown when the regency led by Prince Paul was ended and King Peter II fully assumed power. On 6 April 1941, less than two weeks after Yugoslavia had signed onto the Tripartite Pact, the Axis invaded Yugoslavia. By 18 April, the country was conquered and occupied by the Axis powers.

Background

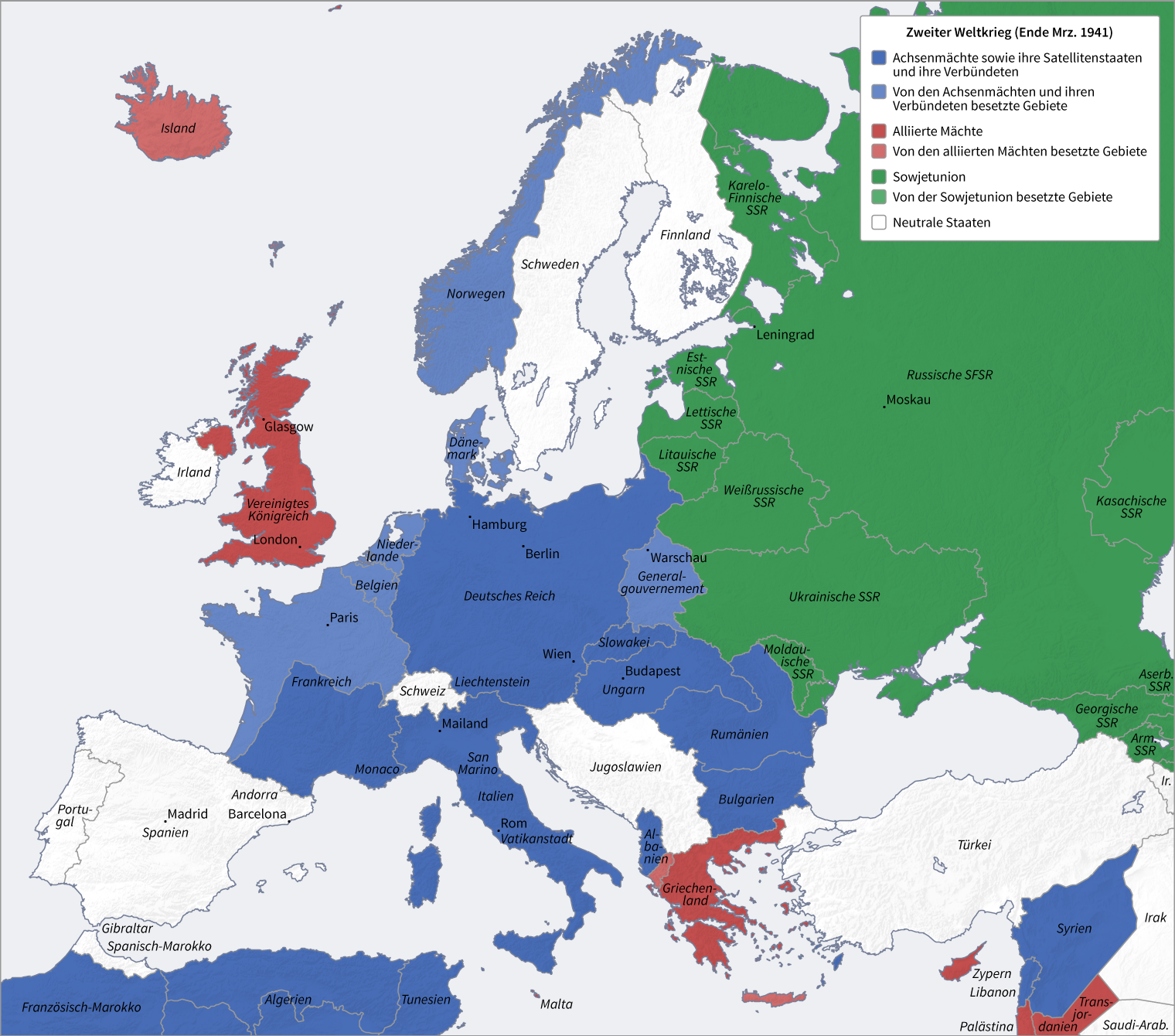

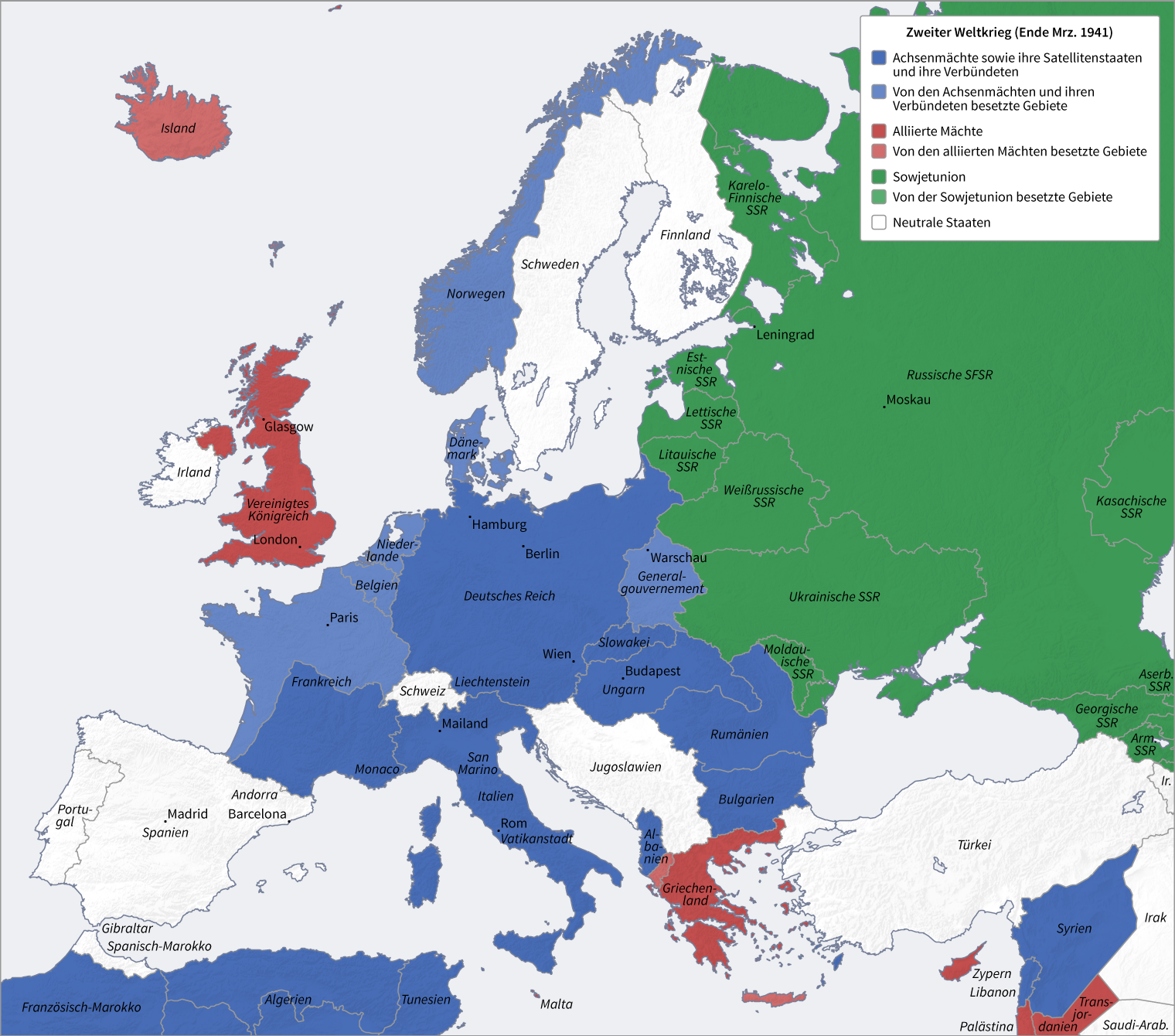

After the French armistice in June 1940, only the

After the French armistice in June 1940, only the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

seemed to have any chance of winning a fight against the Germans, with even it having a greater chance of negotiating a humiliating peace. Thus, the historian Vladislav Sotirović wrote that "no wonder British politicians and diplomats tried by all means, including military coups, to drag any neutral country into war on their side for a final victory against Hitler's Germany". Yugoslavia had been ruled as a dictatorship by the regent, Prince Paul, since the assassination of King Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

in 1934. After the 1938 Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

, the German annexation of Austria; the 1939 Italian occupation of Albania

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

; and the accession of Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria to the Axis Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

from 20 November 1940 to 1 March 1941, Yugoslavia was bordered by Axis powers on all sides except the southern border with Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

. All of those factors, combined with traditional Croatian separatism, caused Paul to be in a great psychological, political and patriotic dilemma in March 1941 on how to resist Hitler's diplomatic pressures and concrete political offers to sign Yugoslavia's accession to the pact. He was unable to stall since Hitler was in a hurry to start the Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the German invasion of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Also, the potential of Croatian betrayal during a German invasion was Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

's main argument during its negotiations with Belgrade.

In the spring of 1941, Yugoslavia could rely only on Britain, which had more economic and population resources than Germany because of its colonies in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Yugoslavia needed quick military aid, which Britain could offer, if the former rejected the pact.

Paul was pro-British and himself a relative of British King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

. Since Paul gave the impression that he would rather resign than turn his back on Britain, Hitler viewed him as a British puppet in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

.

There was also the perceived risk of a communist fifth column because of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

, which made General Milan Nedić

Milan Nedić ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Недић; 2 September 1878 – 4 February 1946) was a Yugoslav and Serbian army general and politician who served as the chief of the General Staff of the Royal Yugoslav Army and minister of war in the R ...

prepare a plan in December 1940 to open six internment camps for communists if it was necessary. Nedić also proposed for the Yugoslav Army to take Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

before Italian troops could do so after the November 1940 Italian invasion of Greece

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

since the loss of that port would make eventual British military aid impossible if Yugoslavia was invaded.

The Greeks, however, held firm against the Italians and even entered Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, where the Italian invasion had begun. Nedić's plan for the communists was uncovered by a spy, the young officer Živadin Simić, in the War Ministry; he copied the two-page document, which was then quickly handed out in Belgrade by the communists.

It was crucial for Hitler to solve the questions of Yugoslavia and Greece before he attacked the Soviet Union since he believed that Britain, which was, along with France, at war with Germany, would accept peace only when the Soviets could no longer threaten Germany. (London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

held the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact as dishonest, volatile and forced by the foreign situation.)

The invasion of the Soviet Union needed the Balkans to be pro-German, and the only unreliable countries in the region were Yugoslavia, the Serbs being traditional enemies of Germany, and Greece, which had been invaded by Italy on its own accord after the German annexation of Austria, but it became clear that Benito Mussolini could not manage in Greece on his own.

The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

in Continental Europe was successfully fighting only in Greece. The military and political elimination of Greece and Yugoslavia, as potential British allies, would thus be extremely serious for Britain.

Seven German divisions were thus moved into Bulgaria, and permission for six divisions to cross Yugoslavia into Greece was sought by Paul. On 1 March 1941, Hitler compelled Paul to visit him personally in his favourite resort, in Berchtesgaden. They secretly met in Berghof, Hitler's residence, on 4 March. In an extremely uncomfortable discussion for Paul, Hitler said that after he would expel British troops from Greece, he would invade the Soviet Union in the summer to destroy bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

.

Yugoslav historiography is mostly silent about the fact that Hitler offered Paul someone of the latter's Karađorđević dynasty

The Karađorđević dynasty ( sr-Cyrl, Динасија Карађорђевић, Dinasija Karađorđević, Карађорђевићи / Karađorđevići, ) or House of Karađorđević ( sr-Cyrl, Кућа Карађорђевић, Kuća Karađ ...

to become the emperor of Russia. That was hinted to be Paul himself, whose his regency mandate would end on 6 September 1941, when Peter II would become an adult and thus the legitimate king of Yugoslavia. However, the offer, which was more imaginary than realistic, was not crucial in influencing Paul's decision to accede to the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941 since it was ''Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' (; ) refers to enacting or engaging in diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly binding itself to explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical ...

'' that was the ultimate factor.

Paul had first addressed British diplomatic circles in Belgrade and London to urge help and protection, but Britain offered no military aid to Yugoslavia, despite doing so for Greece. The British sought for a Yugoslav military engagement against Germany, which was then defeating Britain, and promised an adequate reward after their victory.

During the negotiations with Hitler, Paul feared that London would demand a formal public declaration of friendship with Britain that would only anger Germany but bring no good. Concrete British aid was out of the question, especially since Yugoslavia had bordered Germany since the annexation of Austria. The Yugoslav Army was inadequately armed and so would not stand a chance against Germany, which had won the Battle of France only a year earlier.

On 12 January 1941, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

informed Paul that Yugoslav neutrality was not enough. The German and British demands thus differed enormously since the Germans sought only neutrality and a nonaggression pact, but the British demanded open conflict. On 6 March, Yugoslav War Minister Petar Pešić, despite being supported by the British since he was anti-German, laid out the slim chances of Yugoslavia against Germany. He stressed that the Germans would quickly take over the northern Yugoslavia with Belgrade, Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital and largest city of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb stands near the international border between Croatia and Slov ...

and Ljubljana

Ljubljana (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. It is the country's cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the are ...

and then force the Yugoslav Army to retreat into the Herzegovinian Mountains, where the army could hold out for no more than six weeks before it surrendered since there were not enough weapons, ammunition and food.

Accordingly, the next day, Dragiša Cvetković sent his demands to the German embassy in Belgrade: the respect of the political sovereignty and the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia, the rejection of military aid from or the transport of troops across Yugoslavia during the war and the taking into consideration of the country's interest for an access on the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

during the postwar political reorganisation of Europe.

Negotiations

November 1940

On 28 November 1940, Yugoslav Foreign Minister Aleksandar Cincar-Marković met with Hitler at Berghof. Hitler spoke of his plans of the "consolidation of Europe" and called for the conclusion of a nonaggression pact with Germany and Italy. Although the Yugoslav government agreed, Hitler immediately answered that it was not enough by not meeting the need for the improvement of relations with the Axis powers, and the question of Yugoslavia's accession to the Tripartite Pact needed to be discussed.February 1941

On 14 February 1941, Prime MinisterDragiša Cvetković

Dragiša Cvetković ( sr-cyr, Драгиша Цветковић; 15 January 1893 – 18 February 1969) was a Yugoslav politician active in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He served as the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1939 to 1941. ...

and Foreign Minister Cincar-Marković met with Hitler, who insisted on a quick decision on accession since it was "Yugoslavia's last chance". Hitler had modified his demands by making special concessions to Yugoslavia that would include nothing "contrary to her military traditions and her national honour". Hitler did not demand the passage of troops, the use of railways, the installation of military bases or military collaboration with Yugoslavia and guaranteed its national sovereignty and territorial integrity. Finally, Hitler said, "What I am proposing to you is not in fact the Tripartite Pact". The Yugoslavs, however, managed to refuse and to delay the negotiations by noting that the decision lay in Prince Paul.

4 March 1941

On 4 March 1941, Prince Paul secretly met with Hitler at Berghof, where no obligations were taken, and Paul noted that he needed to consult with his advisers and government. Hitler had offered concrete guarantees and told Paul that the accession would have "a purely formal character".6–14 March 1941

On 6 March, the Crown Council was summoned, and Prince Paul informed of Hitler's demand for accession. Cincar-Marković presented the foreign situation and the problems related to Yugoslav accession, and Pešić portrayed the poor military situation. It was generally concluded from the discussions that accession would occur but that certain limitations and reserves were be demanded from Germany, with Cincar-Marković in charge of drafting those points, which would be held in highest secrecy. The conference showed that the question of accession was very serious and, with respect to public opinion, very difficult.

On 6 March, the Crown Council was summoned, and Prince Paul informed of Hitler's demand for accession. Cincar-Marković presented the foreign situation and the problems related to Yugoslav accession, and Pešić portrayed the poor military situation. It was generally concluded from the discussions that accession would occur but that certain limitations and reserves were be demanded from Germany, with Cincar-Marković in charge of drafting those points, which would be held in highest secrecy. The conference showed that the question of accession was very serious and, with respect to public opinion, very difficult. The next day, Cincar-Marković called Viktor von Heeren, the German minister in Belgrade, to the ministry and informed him of the Crown Council had agreed to Hitler's wish for Yugoslav accession to the pact. Simultaneously, an uneasiness, sparked by anti-Yugoslav manifestations and the negative articles in the media in Bulgaria in recent days, came to the fore.

Then, Ribbentrop was asked to clarify through Heeren whether Yugoslavia would receive a written statement from Germany and Italy if it acceded that Yugoslavia's sovereignty and territorial integrity would be respected; that no Yugoslav military aid would be requested and, during the creation of a new order in Europe, that the Yugoslav interest in free access to the Aegean Sea through Thessaloniki would be considered.

Cincar-Marković noted while he presented those points that there had already been a consensus on all questions. He then informed Paul that Ribbentrop had offered written guarantees. To clarify the situation, Cincar-Marković again asked for a precise answer from the German government to confirm those questions, which would help the Yugoslav government to implement the desired policy.

On 8 March, Heeren strictly confidentially contacted the German ministry. He stated that he had a strong impression that Yugoslavia had already decided that it would soon join the pact if the Germans either fulfilled the demands presented by Cincar-Marković or only slightly amended the German-Italian written statements. Heeren believed that Ribbentrop's incentive for another discussion with Paul was very appropriate and would be best held at the Brdo Castle, near Kranj.

In Belgrade's political and military circles, joining the German camp was generally discussed, but the thought that it would come in stages, with the help of government statements, prevailed and that by not acceding the pact would spare the population's hostile mood. The same day that Heeren contacted Ribbentrop about the latter's instructions, Heeren decided to see Cincar-Marković to state immediately that the German-Italian response to all three points had been positive. Heeren then warned Cincar-Marković the situation made it seem that it was in the best interest for Yugoslavia to decide on its accession as fast as possible.

On 9 March, continuing his phone conversation, Ribbentrop stated to Heeren from

The next day, Cincar-Marković called Viktor von Heeren, the German minister in Belgrade, to the ministry and informed him of the Crown Council had agreed to Hitler's wish for Yugoslav accession to the pact. Simultaneously, an uneasiness, sparked by anti-Yugoslav manifestations and the negative articles in the media in Bulgaria in recent days, came to the fore.

Then, Ribbentrop was asked to clarify through Heeren whether Yugoslavia would receive a written statement from Germany and Italy if it acceded that Yugoslavia's sovereignty and territorial integrity would be respected; that no Yugoslav military aid would be requested and, during the creation of a new order in Europe, that the Yugoslav interest in free access to the Aegean Sea through Thessaloniki would be considered.

Cincar-Marković noted while he presented those points that there had already been a consensus on all questions. He then informed Paul that Ribbentrop had offered written guarantees. To clarify the situation, Cincar-Marković again asked for a precise answer from the German government to confirm those questions, which would help the Yugoslav government to implement the desired policy.

On 8 March, Heeren strictly confidentially contacted the German ministry. He stated that he had a strong impression that Yugoslavia had already decided that it would soon join the pact if the Germans either fulfilled the demands presented by Cincar-Marković or only slightly amended the German-Italian written statements. Heeren believed that Ribbentrop's incentive for another discussion with Paul was very appropriate and would be best held at the Brdo Castle, near Kranj.

In Belgrade's political and military circles, joining the German camp was generally discussed, but the thought that it would come in stages, with the help of government statements, prevailed and that by not acceding the pact would spare the population's hostile mood. The same day that Heeren contacted Ribbentrop about the latter's instructions, Heeren decided to see Cincar-Marković to state immediately that the German-Italian response to all three points had been positive. Heeren then warned Cincar-Marković the situation made it seem that it was in the best interest for Yugoslavia to decide on its accession as fast as possible.

On 9 March, continuing his phone conversation, Ribbentrop stated to Heeren from Fuschl am See

Fuschl am See is an Austrian municipality in the district of Salzburg-Umgebung, in the state of Salzburg. It is located at the east end of the Fuschlsee, between the city of Salzburg and Bad Ischl. As of 2018, the community has approximately 1,5 ...

that Germany was ready to recognise its respect of Yugoslav sovereignty and territorial integrity in a special note, which could be publicised by the Yugoslav government.

The Germans were ready to promise that no request on passage or transfer of troops would be made to Yugoslavia during the war, which could be publicised if the Yugoslav government thought that internal politics made it necessary. That and the announcement's timing could be discussed during the pact's conclusion.

20–24 March 1941

On 20 March, three Yugoslav ministers (Branko Čubrilović, Mihailo Konstantinović andSrđan Budisavljević

Srđan Budisavljević (8 December 1883 – 20 February 1968) was a politician and lawyer born in Požega. Budisavljević stuied law in Zagreb and Berlin before being elected to the Sabor of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia in 1908 as a represent ...

) resigned in protest.

After consultations with British and American ministers, the Crown Council decided that the military situation was hopeless and voted 15–3 in favour of accession.

Signing

On 25 March, the pact was signed at the

On 25 March, the pact was signed at the Belvedere Belvedere (from Italian, meaning "beautiful sight") may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Belvedere, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

Africa

* Belvedere (Casablanca), a neighborhood in Casablanca, Morocco

*Belvedere, Harare, Zi ...

, in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, the main signatories being Ribbentrop and Cvetković. An official banquet was held, which Hitler complained felt like a funeral party. The German side had accepted the demands that had been made by Paul and Cvetković although both had actually hoped that Hitler would not accept them so that they could prolong the negotiations. The agreement stated that Germany would respect the sovereignty and the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia and that the Axis powers would neither seek permission to transport troops across Yugoslavia nor request any military assistance. The Yugoslav ambassador to Germany, Ivo Andrić

Ivo Andrić ( sr-Cyrl, Иво Андрић, ; born Ivan Andrić; 9 October 1892 – 13 March 1975) was a Yugoslav novelist, poet and short story writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961. His writings dealt mainly with life in ...

, better known for being a writer, transcribed the document.

German radio later announced that "the Axis Powers would not demand the right of passage of troops or war materials" although the official document mentioned only troops and omitted any mention of war materials. Likewise, no pledge to consider giving Thessalonika to Yugoslavia appeared in the document.

Aftermath

Demonstrations

The day after the signing of the pact, demonstrators gathered on the streets of Belgrade and shouted, "Better the grave than a slave, better a war than the pact" ( sh-Latn, Bolje grob nego rob, Bolje rat nego pakt, links=no).Coup d'état

On March 27, the regime was overthrown in a

On March 27, the regime was overthrown in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

that had British support. King Peter II was declared to be of age despite being only 17. The new Yugoslav government, under Prime Minister and General Dušan Simović

Dušan Simović (; 28 October 1882 – 26 August 1962) was a Yugoslav Serb army general who served as Chief of the General Staff of the Royal Yugoslav Army and as the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia in 1940–1941.

Biography

Simović, born o ...

, refused to ratify Yugoslavia's signing of the Tripartite Pact and started negotiations with the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

The enraged Hitler issued Directive 25 as an answer to the coup and attacked both Yugoslavia and Battle of Greece, Greece on April 6.

The German Air Force Operation Retribution (1941), bombed Belgrade for three days and nights. German German Army (Wehrmacht), ground troops moved in, and Yugoslavia surrendered on April 17.

Legacy

In September 1945, the State Commission of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia called Paul a "criminal", one reason being that he had caused Yugoslavia to join the Tripartite Pact. Serbia rehabilitated him on 14 December 2011.See also

* Germany–Yugoslavia relationsReferences

Sources

* * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Foreign relations of Yugoslavia 1941 in military history 1941 in Yugoslavia Foreign relations of Yugoslavia Military alliances involving Nazi Germany Military alliances involving Yugoslavia Treaties concluded in 1941 Treaties of Nazi Germany Treaties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia World War II treaties Germany–Yugoslavia relations Politics of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia March 1941 events 1940s in Vienna Axis powers Politics of World War II