Atlantic U-boat Campaign (World War I) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Atlantic U-boat campaign of World War I (sometimes called the "First Battle of the Atlantic", in reference to the

On 5 September 1914, commanded by Lieutenant

On 5 September 1914, commanded by Lieutenant  Three weeks later, on 15 October, Weddigen also sank the old cruiser , and the crew of ''U-9'' became national heroes. Each was awarded the

Three weeks later, on 15 October, Weddigen also sank the old cruiser , and the crew of ''U-9'' became national heroes. Each was awarded the

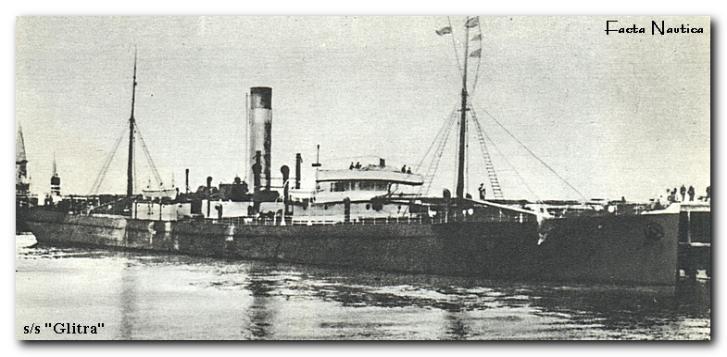

The first attacks on merchant ships had started in October 1914. On 20 October became the first British merchant vessel to be sunk by a German submarine in World War I. ''Glitra'', bound from

The first attacks on merchant ships had started in October 1914. On 20 October became the first British merchant vessel to be sunk by a German submarine in World War I. ''Glitra'', bound from

Britons believed before the war that the United Kingdom would starve without North American food;

Britons believed before the war that the United Kingdom would starve without North American food;

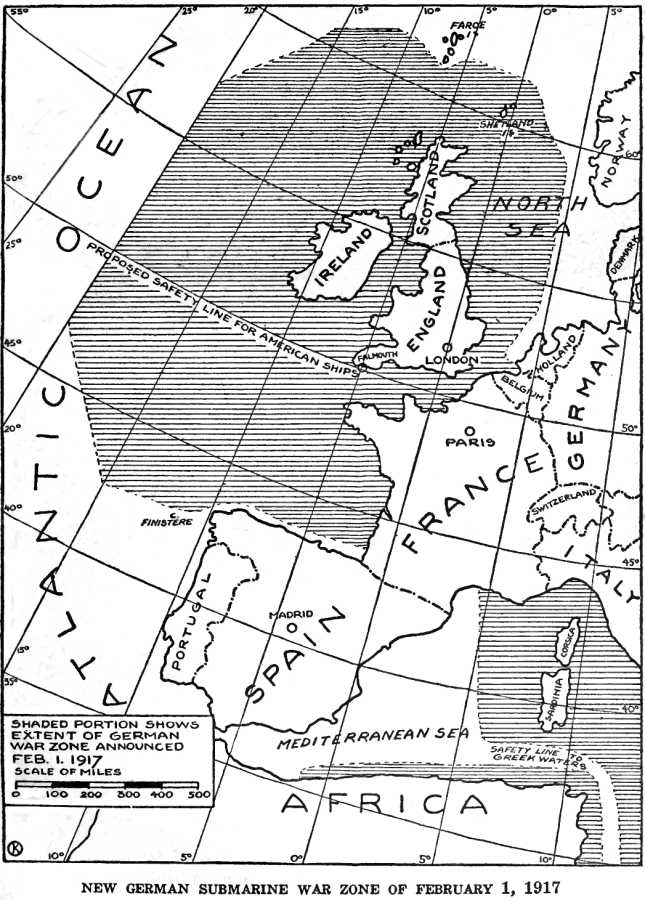

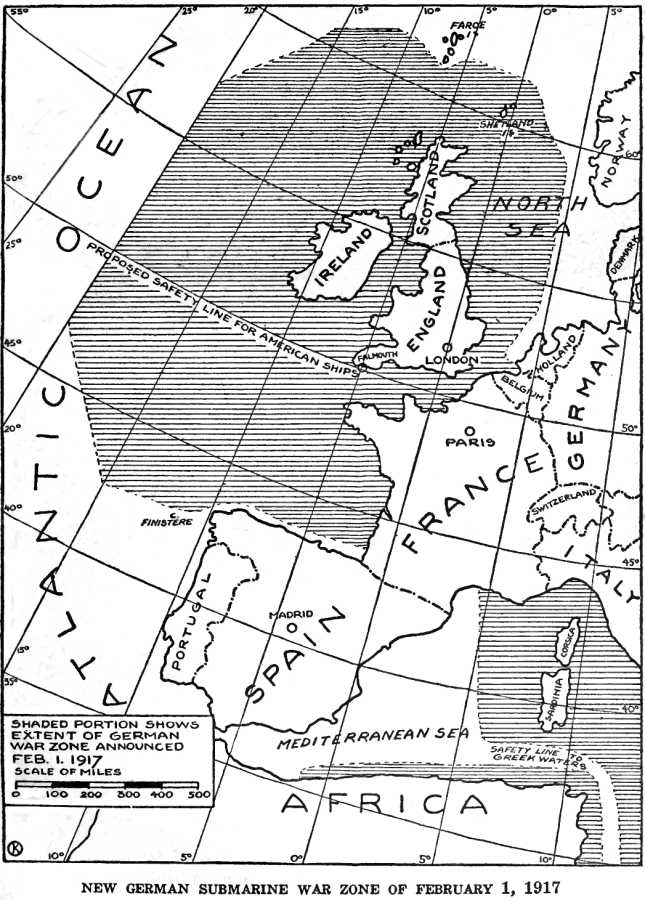

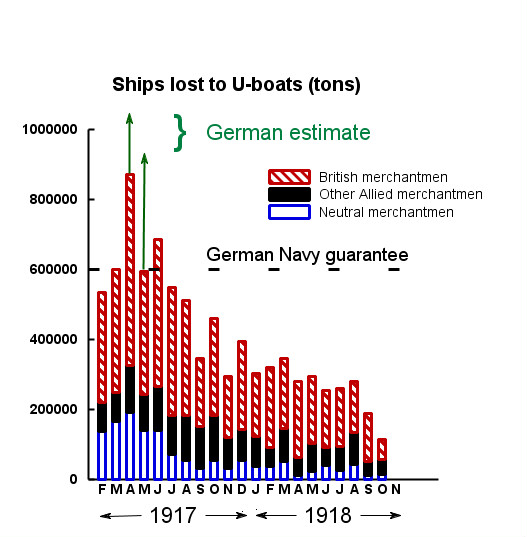

In 1917 Germany decided to resume full unrestricted submarine warfare. It was expected to bring America into the war, but the Germans gambled that they could defeat Britain by this means before the US could mobilize. German planners estimated that if the sunk tonnage were to exceed 600,000 tons per month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months.

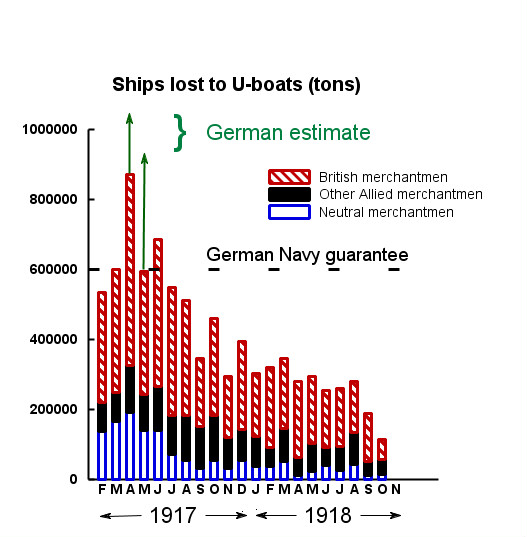

In February 1917 U-boats sank over 414,000 GRT in the war zone around Britain, 80% of the total for the month; in March they sank over 500,000 (90%), in April over 600,000 of 860,000 GRT, the highest total sinkings of the war. This, however was the high point.

In May, the first convoys were introduced, and were immediately successful. Overall losses started to fall; losses to ships in convoy fell dramatically. In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats. By comparison 356 were lost sailing independently.

As shipping losses fell, U-boat losses rose; during the period May to July 1917, 15 U-boats were destroyed in the waters around Britain, compared to 9 the previous quarter, and 4 for the quarter before the campaign was renewed.

As the campaign became more intense, it also became more brutal. 1917 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status. In January, was sunk by ; in March, by ; in June, and by .

As U-boats became more wary, encounters with Q-ships also became more intense. In February 1917 was sunk by , but only after

In 1917 Germany decided to resume full unrestricted submarine warfare. It was expected to bring America into the war, but the Germans gambled that they could defeat Britain by this means before the US could mobilize. German planners estimated that if the sunk tonnage were to exceed 600,000 tons per month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months.

In February 1917 U-boats sank over 414,000 GRT in the war zone around Britain, 80% of the total for the month; in March they sank over 500,000 (90%), in April over 600,000 of 860,000 GRT, the highest total sinkings of the war. This, however was the high point.

In May, the first convoys were introduced, and were immediately successful. Overall losses started to fall; losses to ships in convoy fell dramatically. In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats. By comparison 356 were lost sailing independently.

As shipping losses fell, U-boat losses rose; during the period May to July 1917, 15 U-boats were destroyed in the waters around Britain, compared to 9 the previous quarter, and 4 for the quarter before the campaign was renewed.

As the campaign became more intense, it also became more brutal. 1917 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status. In January, was sunk by ; in March, by ; in June, and by .

As U-boats became more wary, encounters with Q-ships also became more intense. In February 1917 was sunk by , but only after

In January, six U-boats were destroyed in the theatre; this also became the average loss for the year.

The Allies continued to try to block access through the Straits of Dover, with the

In January, six U-boats were destroyed in the theatre; this also became the average loss for the year.

The Allies continued to try to block access through the Straits of Dover, with the  In the summer, too, steps were taken to reduce the effectiveness of the High Seas Flotillas. In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the

In the summer, too, steps were taken to reduce the effectiveness of the High Seas Flotillas. In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the

Atlantic U-boat Campaign

, in

* Karau, Mark D.

Submarines and Submarine Warfare

, in

{{Uboat U-boats U-boat Campaign (World War I) Atlantic operations of World War I

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

campaign of that name) was the prolonged naval conflict between German submarines

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

and the Allied navies in Atlantic waters—the seas around the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

, the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

and the coast of France.

Initially the U-boat campaign was directed against the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

. Later U-boat fleet action was extended to include action against the trade routes of the Allied powers. This campaign was highly destructive, and resulted in the loss of nearly half of Britain's merchant marine fleet during the course of the war. To counter the German submarines, the Allies moved shipping into convoys guarded by destroyers, blockades such as the Dover Barrage

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidston ...

and minefields were laid, and aircraft patrols monitored the U-boat bases.

The U-boat campaign was not able to cut off supplies before the US entered the war in 1917 and in later 1918, the U-boat bases were abandoned in the face of the Allied advance.

The tactical successes and failures of the Atlantic U-boat Campaign would later be used as a set of available tactics in World War II in a similar U-boat war against the British Empire.

1914: Initial campaign

First patrols

On 6 August 1914, two days after Britain had declared war on Germany, the GermanU-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s , , , , , , , , , and sailed from their base in Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possession ...

to attack Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

warships in the North Sea in the first submarine war patrols in history.

The U-boats sailed north, hoping to encounter Royal Navy squadrons between Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

and Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

. On 8 August, one of ''U-9''s engines broke down and she was forced to return to base. On the same day, off Fair Isle

Fair Isle (; sco, Fair Isle; non, Friðarey; gd, Fara) is an island in Shetland, in northern Scotland. It lies about halfway between mainland Shetland and Orkney. It is known for its bird observatory and a traditional style of knitting. Th ...

, ''U-15'' sighted the British battleships , , and on manoeuvres and fired a torpedo at ''Monarch''. This failed to hit, and succeeded only in putting the battleships on their guard. At dawn the next morning, the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, which was screening the battleships, came into contact with the U-boats. sighting ''U-15'', which was lying on the surface. There was no sign of any lookouts on the U-boat and sounds of hammering could be heard, as though her crew were performing repairs. ''Birmingham'' immediately altered course and rammed ''U-15'' just behind her conning tower. The submarine was cut in two and sank with all hands.

On 12 August, seven U-boats returned to Heligoland; ''U-13'' was also missing, and it was thought she had been mined. While the operation was a failure, it caused the Royal Navy some uneasiness, disproving earlier estimates as to U-boats' radius of action and leaving the security of the Grand Fleet's unprotected anchorage at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

open to question. On the other hand, the ease with which ''U-15'' had been destroyed by ''Birmingham'' encouraged the false belief that submarines were no great danger to surface warships.

First successes

On 5 September 1914, commanded by Lieutenant

On 5 September 1914, commanded by Lieutenant Otto Hersing

Otto Hersing (30 November 1885 – 1 July 1960) was a German naval officer who served as U-boat commander in the '' Kaiserliche Marine'' and the ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'' during World War I.

In September 1914, while in command of the German '' U- ...

made history when he torpedoed the Royal Navy light cruiser . The cruiser's magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

exploded, and the ship sank in four minutes, taking 259 of her crew with her. It was the first combat victory of the modern submarine.

The German U-boats were to get even luckier on 22 September. Early in the morning of that day, a lookout on the bridge of ''U-9'', commanded by Lieutenant Otto Weddigen

Otto Eduard Weddigen (15 September 1882 – 18 March 1915) was an Imperial German Navy U-boat commander during World War I. He was awarded the Pour le Mérite, Germany's highest honour, for sinking four British warships.

Biography and car ...

, spotted a vessel on the horizon. Weddigen ordered the U-boat to submerge immediately, and the submarine went forward to investigate. At closer range, Weddigen discovered three old Royal Navy armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast en ...

s, , , and . These three vessels were not merely antiquated, but were staffed mostly by reservists, and were so clearly vulnerable that a decision to withdraw them was already filtering up through the bureaucracy of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

. The order did not come soon enough for the ships. Weddigen sent one torpedo into ''Aboukir''. The captains of ''Hogue'' and ''Cressy'' assumed ''Aboukir'' had struck a mine and came up to assist. ''U-9'' put two torpedoes into ''Hogue'', and then hit ''Cressy'' with two more torpedoes as the cruiser tried to flee. The three cruisers sank in less than an hour, killing 1,460 British sailors.

Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

Second Class, except for Weddigen, who received the Iron Cross First Class. The sinkings caused alarm within the British Admiralty, which was increasingly nervous about the security of the Scapa Flow anchorage, and the fleet was sent to ports in Ireland and the west coast of Scotland until adequate defenses were installed at Scapa Flow. This, in a sense, was a more significant victory than sinking a few old cruisers; the world's most powerful fleet had been forced to abandon its home base.

On 18 October, SM ''U-27'' sank HMS ''E3'', the first instance of one submarine sinking another.

End of the first campaign

These concerns were well-founded. On 23 November ''U-18'' penetrated Scapa Flow via Hoxa Sound, following a steamer through the boom and entering the anchorage with little difficulty. However, the fleet was absent, being dispersed in anchorages on the west coast of Scotland and Ireland. As ''U-18'' was making her way back out to the open sea, her periscope was spotted by a guard boat. The trawler ''Dorothy Gray'' altered course and rammed the periscope, rendering it unserviceable. ''U-18'' then suffered a failure of her diving plane motor and the boat became unable to maintain her depth, at one point even impacting the seabed. Eventually, her captain was forced to surface and scuttle his command, and all but one crew-member were picked up by British boats. The last success of the year came on 31 December. ''U-24'' sighted the British battleship on manoeuvres in theEnglish Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

and torpedoed her. ''Formidable'' sank with the loss of 547 of her crew. The C-in-C Channel Fleet, Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

, was criticized for not taking proper precautions during the exercises, but was cleared of the charge of negligence. Bayly later served with distinction as commander of the anti-submarine warfare forces at Queenstown.

1915: War on commerce

First attacks on merchant ships

The first attacks on merchant ships had started in October 1914. On 20 October became the first British merchant vessel to be sunk by a German submarine in World War I. ''Glitra'', bound from

The first attacks on merchant ships had started in October 1914. On 20 October became the first British merchant vessel to be sunk by a German submarine in World War I. ''Glitra'', bound from Grangemouth

Grangemouth ( sco, Grangemooth; gd, Inbhir Ghrainnse, ) is a town in the Falkirk council area, Scotland. Historically part of the county of Stirlingshire, the town lies in the Forth Valley, on the banks of the Firth of Forth, east of Falkir ...

to Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

, Norway, was stopped and searched by ''U-17'', under the command of Kapitänleutnant Johannes Feldkirchener. The operation was performed broadly in accordance with the cruiser rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

, the crew being ordered into the lifeboats before ''Glitra'' was sunk by having her seacock

A seacock is a valve on the hull of a boat or a ship, permitting water to flow into the vessel, such as for cooling an engine or for a salt water faucet; or out of the boat, such as for a sink drain or a toilet. Seacocks are often a Kingston va ...

s opened. It was the first time in history a submarine sank a merchant ship.

Less than a week later, on 26 October, ''U-24'' became the first submarine to attack an unarmed merchant ship without warning, when she torpedoed the steamship , with 2,500 Belgian refugees aboard. Although the ship did not sink, and was towed into Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

, 40 people died, mainly due to panic. The U-boat's commander, Rudolf Schneider, claimed he had mistaken her for a troop transport.

On 30 January 1915, , commanded by ''Kapitänleutnant'' Otto Dröscher, torpedoed and sank the steamships , and without warning, and on 1 February fired a torpedo at, but missed, the hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. I ...

, despite her being clearly identifiable as a hospital ship by her white paintwork with green bands and red crosses.

Unrestricted submarine warfare

Britons believed before the war that the United Kingdom would starve without North American food;

Britons believed before the war that the United Kingdom would starve without North American food; W. T. Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was a British newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst ed ...

wrote in 1901 that without it "We should be face to face with famine". On 4 February 1915, the first unrestricted campaign against Allied trade was started. The U-boat had several deficiencies for a commerce raider; its low speed, even on the surface, made it scarcely faster than many merchant ships, while its light gun armament was inadequate against larger vessels. To use the U-boat's chief weapon, the attack without warning, using torpedoes, meant abandoning the stop-and-search required to avoid harming neutrals.

In the first month 29 ships totalling were sunk, a pace of destruction which was maintained throughout the summer. As the sinkings increased, so too did the number of politically damaging incidents. On 19 February, ''U-8'' torpedoed ''Belridge'', a neutral tanker travelling between two neutral ports; in March U-boats sank ''Hanna'' and ''Medea'', a Swedish and a Dutch freighter; in April two Greek vessels.

In March also, ''Falaba'' was sunk, with the loss of one US life, and in April ''Harpalyce'', a Belgian Relief ship, was sunk. On 7 May, ''U-20'' sank with the loss of 1,198 lives, 128 of them US citizens. These incidents caused outrage amongst neutrals and the scope of the unrestricted campaign was scaled back in September 1915 to lessen the risk of those nations entering the war against Germany.

British countermeasures were largely ineffective. The most effective defensive measures proved to be advising merchantmen to turn towards the U-boat and attempt to ram, forcing it to submerge. Over half of all attacks on merchant ships by U-boats were defeated in this way. This response freed the U-boat to attack without warning, however. On 20 March 1915, this tactic was used by the Great Eastern Railway

The Great Eastern Railway (GER) was a pre-grouping British railway company, whose main line linked London Liverpool Street to Norwich and which had other lines through East Anglia. The company was grouped into the London and North Eastern Ra ...

packet

Packet may refer to:

* A small container or pouch

** Packet (container), a small single use container

** Cigarette packet

** Sugar packet

* Network packet, a formatted unit of data carried by a packet-mode computer network

* Packet radio, a fo ...

to escape an attack by . For this her captain, Charles Fryatt

Charles Algernon Fryatt (2 December 1872 – 27 July 1916) was a British merchant seaman who was court martialled by the Imperial German Navy for attempting to ram a German U-boat in 1915. When his ship, the , was captured off occupied Belgium ...

, was executed after being captured by the Germans in June 1916 provoking international condemnation.

Another option was arming ships for self-defence, which, according to the Germans, put them outside the protection of the cruiser rules.

Another option was to arm and man decoy ships with hidden guns, the so-called Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

. A variant on the idea was to equip small vessels with a submarine escort. In 1915, three U-boats were sunk by Q-ships, and two more by submarines accompanying trawlers. In June also was sunk by while attacking ''Taranaki'', and in July ''U-23'' was sunk by ''C-27'' attacking ''Princess Louise''. Also in July ''U-36'' was sunk by the Q-ship ''Prince Charles'', and in August and September and were sunk by , the former in the notorious ''Baralong'' Incident.

There were, however, no means to detect submerged U-boats, and attacks on them were limited to efforts to damage their periscopes with hammers and dropping guncotton bombs. Use of nets to ensnare U-boats was also examined, as was a destroyer, , fitted with a spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

.

In all, 16 U-boats were destroyed during this phase of the campaign, while they themselves sank 370 ships totalling 750,000 GRT.

1916: In support of the High Seas fleet

In 1916 the German Navy returned to a strategy of using the U-boats to erode theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

's numerical superiority by staging a series of operations designed to lure the Grand Fleet into a U-boat trap. Due to the U-boats' poor speed compared to the main battle fleet these operations required U-boat patrol lines to be set up, while the High Seas fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

manoeuvred to draw the Grand Fleet to them.

Several of these operations were staged, in March and April 1916, but with no success. Ironically, the major fleet action which did take place, the Battle of Jutland, in May 1916, saw no U-boat involvement at all; the fleets met and engaged largely by chance, and there were no U-boat patrols anywhere near the battle area. A further series of operations, in August and October 1916, were similarly unfruitful, and the strategy was abandoned in favour of resuming commerce warfare.

1917: Renewed "unrestricted" campaign

In 1917 Germany decided to resume full unrestricted submarine warfare. It was expected to bring America into the war, but the Germans gambled that they could defeat Britain by this means before the US could mobilize. German planners estimated that if the sunk tonnage were to exceed 600,000 tons per month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months.

In February 1917 U-boats sank over 414,000 GRT in the war zone around Britain, 80% of the total for the month; in March they sank over 500,000 (90%), in April over 600,000 of 860,000 GRT, the highest total sinkings of the war. This, however was the high point.

In May, the first convoys were introduced, and were immediately successful. Overall losses started to fall; losses to ships in convoy fell dramatically. In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats. By comparison 356 were lost sailing independently.

As shipping losses fell, U-boat losses rose; during the period May to July 1917, 15 U-boats were destroyed in the waters around Britain, compared to 9 the previous quarter, and 4 for the quarter before the campaign was renewed.

As the campaign became more intense, it also became more brutal. 1917 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status. In January, was sunk by ; in March, by ; in June, and by .

As U-boats became more wary, encounters with Q-ships also became more intense. In February 1917 was sunk by , but only after

In 1917 Germany decided to resume full unrestricted submarine warfare. It was expected to bring America into the war, but the Germans gambled that they could defeat Britain by this means before the US could mobilize. German planners estimated that if the sunk tonnage were to exceed 600,000 tons per month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months.

In February 1917 U-boats sank over 414,000 GRT in the war zone around Britain, 80% of the total for the month; in March they sank over 500,000 (90%), in April over 600,000 of 860,000 GRT, the highest total sinkings of the war. This, however was the high point.

In May, the first convoys were introduced, and were immediately successful. Overall losses started to fall; losses to ships in convoy fell dramatically. In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats. By comparison 356 were lost sailing independently.

As shipping losses fell, U-boat losses rose; during the period May to July 1917, 15 U-boats were destroyed in the waters around Britain, compared to 9 the previous quarter, and 4 for the quarter before the campaign was renewed.

As the campaign became more intense, it also became more brutal. 1917 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status. In January, was sunk by ; in March, by ; in June, and by .

As U-boats became more wary, encounters with Q-ships also became more intense. In February 1917 was sunk by , but only after Gordon Campbell

Gordon Muir Campbell, (born January 12, 1948) is a retired Canadian diplomat and politician who was the 35th mayor of Vancouver from 1986 to 1993 and the 34th premier of British Columbia from 2001 to 2011.

He was the leader of the British Co ...

, ''Farnborough''s captain, allowed her to be torpedoed in order to get close enough to engage. In March ''Privet'' sank ''U-85'' in a 40-minute gun battle, but herself sank before reaching harbour.

In April ''Heather'' was attacked by ''U-52'' and was badly damaged; the U-boat escaped unscathed. And a few days later ''Tulip'' was sunk by whose captain was suspicious of her appearance.

1918: Final year

The convoy system was effective in reducing allied shipping losses, while better weapons and tactics made the escorts more successful at intercepting and attacking U-boats. Shipping losses in Atlantic waters were 98 ships (just over 170,000 GRT) in January; after a rise in February they fell again, and did not rise above that level for the rest of the war.Tarrant 1989, p. 148. In January, six U-boats were destroyed in the theatre; this also became the average loss for the year.

The Allies continued to try to block access through the Straits of Dover, with the

In January, six U-boats were destroyed in the theatre; this also became the average loss for the year.

The Allies continued to try to block access through the Straits of Dover, with the Dover Barrage

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidston ...

. Until November 1917 it was ineffective; up to then just two U-boats had been destroyed by the Barrage force, and the Barrage itself had been a magnet for surface raids. After major improvement in the winter of 1917 it became more effective; in the four-month period after mid-December seven U-boats were destroyed trying to transit the area, and by February the High Seas Flotilla boats had abandoned the route in favour of sailing north-about round Scotland, with a consequent loss of effectiveness. The Flanders boats still tried to use the route, but continued to suffer losses, and after March switched their operations to Britain's east coast.

Other measures, particularly against the Flanders flotilla, were the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

, an attempt to blockade access to the sea. These were largely unsuccessful; the Flanders boats were able to maintain access throughout this period.

May 1918 saw the only attempt by the Germans to muster a group attack, the forerunner of the wolf-pack

A pack is a social group of conspecific canines. Packs aren't formed by all canines, especially small sized canines like the Red fox. The number of members in a pack and their social behavior varies from species to species. Social structure is ...

, to counter the Allied convoys.

In May, six U-boats sailed, under the command of K/L Claus Rücker in . On 11 May, ''U-86'' sank one of a pair of ships detached from a convoy in the Channel, but the next day an attack on the troopship led to the destruction of ''U-103'', while was sunk by British submarine . Two more ships were sunk in convoys in the next week, and three independents, but over 100 ships had passed safely through the group's patrol area.

During the summer, the extension of the convoy system and effectiveness of the escorts made the east coast of Britain as dangerous for the U-boats as the Channel had become. In this period, the Flanders flotilla lost a third of its boats, and in the autumn, losses were at 40%. In October, with the German army in full retreat, the Flanders flotilla was forced to abandon its base at Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the country by population.

The area of the whole city a ...

before it was overrun. A number of boats were scuttled there, while the remainder, just ten boats, returned to bases in Germany.

In the summer, too, steps were taken to reduce the effectiveness of the High Seas Flotillas. In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the

In the summer, too, steps were taken to reduce the effectiveness of the High Seas Flotillas. In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea ( no, Norskehavet; is, Noregshaf; fo, Norskahavið) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to ...

, to block U-boat access to the Western Approaches by the north-about route. This huge undertaking involved laying and maintaining minefields and patrols in deep waters over a distance of 300 nautical miles (556 kilometers). The North Sea Mine Barrage

The North Sea Mine Barrage, also known as the Northern Barrage, was a large minefield laid easterly from the Orkney Islands to Norway by the United States Navy (assisted by the Royal Navy) during World War I. The objective was to inhibit the m ...

saw the laying of over 70,000 mines, mostly by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, during the summer of 1918. From September to November 1918, six U-boats were sunk by this measure.Halpern 1995, pp. 438–441.

In July 1918, sailed to Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and took part in the Attack on Orleans

The Attack on Orleans was a naval and air action during World War I on 21 July 1918 when a German submarine fired on a small convoy of barges led by a tugboat off Orleans, Massachusetts, on the eastern coast of the Cape Cod peninsula. Several ...

for about an hour. This was the first time that US soil was attacked by a foreign power's artillery since the Siege of Fort Texas

The siege of Fort Texas marked the beginning of active campaigning by the armies of the United States and Mexico during the Mexican–American War. The battle is sometimes called the siege of Fort Brown. Major Jacob Brown, not to be confused w ...

in 1846 and one of two places in North America to be subject to attack by the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

. The other was the Battle of Ambos Nogales that was allegedly led by two German spies.

On 20 October 1918 Germany suspended submarine warfare, and on 11 November 1918, World War I ended. The last task of the U-Boat Arm was in helping to quell the Wilhelmshaven mutiny, which had broken out when the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

was ordered to sea for a final, doomed sortie. After the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, the remaining U-boats joined the High Seas Fleet in surrender, and were interned at Harwich.

Of the 12.5 million tons of Allied shipping destroyed in World War I, over 8 million tons, two-thirds of the total, had been sunk in the waters of the Atlantic war zone. Of the 178 U-boats destroyed during the war, 153 had been from the Atlantic forces, 77 from the much larger High Seas Flotillas and 76 from the much smaller Flanders force.

See also

* Mediterranean U-boat campaign of World War INotes

References

* * * * * * * * * Holwitt, Joel I. ''"Execute Against Japan"'', PhD dissertation, Ohio State University, 2005. * McKee, Fraser M. "An Explosive Story: The Rise and Fall of the Depth Charge", in ''The Northern Mariner'' (III, #1, January 1993), pp. 45–58.External links

* Abbatiello, JohnAtlantic U-boat Campaign

, in

* Karau, Mark D.

Submarines and Submarine Warfare

, in

{{Uboat U-boats U-boat Campaign (World War I) Atlantic operations of World War I