Arthur St. Clair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur St. Clair ( – August 31, 1818) was a

Under the

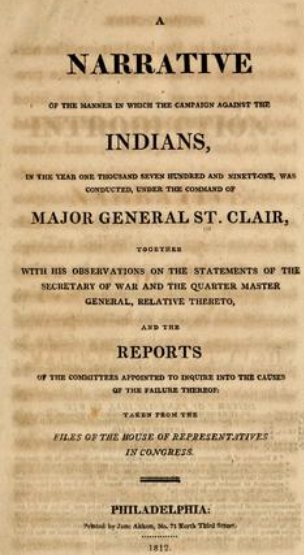

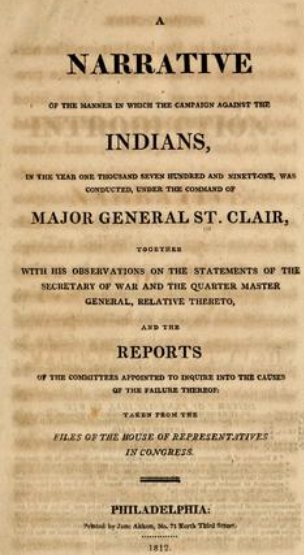

Under the  A

A

online

* *

Ohio Memory

Ohio History Central

The Hermitage – home of Arthur St. Clair

{{DEFAULTSORT:St. Clair, Arthur 1737 births 1818 deaths Adjutants general of the United States Army Continental Army generals Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania Continental Army personnel who were court-martialed Continental Congressmen from Pennsylvania 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians Governors of Northwest Territory Politicians from Cincinnati People from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania American people of the Northwest Indian War Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British military personnel of the French and Indian War People from Thurso Royal American Regiment officers British emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies Commanding Generals of the United States Army

Scottish-American

Scottish Americans or Scots Americans (Scottish Gaelic language, Scottish Gaelic: ''Ameireaganaich Albannach''; sco, Scots-American) are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Scotland. Scottish people, Scottish Americans are cl ...

soldier and politician. Born in Thurso, Scotland, he served in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

before settling in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, where he held local office. During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, he rose to the rank of major general in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

, but lost his command after a controversial retreat from Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French mi ...

.

After the war, he served as President of the Continental Congress

The president of the United States in Congress Assembled, known unofficially as the president of the Continental Congress and later as the president of the Congress of the Confederation, was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress, the ...

, which during his term passed the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

. He was then made governor of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

in 1788, and then the portion that would become Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

in 1800. In 1791, St. Clair commanded the American forces in what was the United States' worst ever defeat by the Native Americans, which became known as St. Clair's defeat. Politically out-of-step with the Jefferson administration, he was replaced as governor in 1802.

Early life and career

St. Clair was born inThurso

Thurso (pronounced ; sco, Thursa, gd, Inbhir Theòrsa ) is a town and former burgh on the north coast of the Highland council area of Scotland. Situated in the historical County of Caithness, it is the northernmost town on the island of Great ...

, Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded by ...

, Scotland. Little is known of his early life. Early biographers estimated his year of birth as 1734, but subsequent historians uncovered a birth date of March 23, 1736, which in the modern calendar system means that he was born in 1737. His parents, unknown to early biographers, were probably William Sinclair, a merchant, and Elizabeth Balfour.Gregory Evans Dowd. "St. Clair, Arthur", ''American National Biography Online

The ''American National Biography'' (ANB) is a 24-volume biographical encyclopedia set that contains about 17,400 entries and 20 million words, first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the American Council of Lea ...

'', February 2000. He reportedly attended the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

before being apprenticed to the renowned physician William Hunter.

In 1757, St. Clair purchased a commission in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, Royal American Regiment

The King's Royal Rifle Corps was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army that was originally raised in British North America as the Royal American Regiment during the phase of the Seven Years' War in North America known in the United St ...

, and came to America with Admiral Edward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during ...

's fleet for the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

. He served under General Jeffery Amherst

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst, (29 January 1717 – 3 August 1797) was a British Army officer and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the British Army. Amherst is credited as the architect of Britain's successful campaign ...

at the capture of Louisburg, Nova Scotia, on July 26, 1758. On April 17, 1759, he received a lieutenant's commission and was assigned under the command of General James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a Major-general (United Kingdom), major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the Kingdom of France, French ...

, under whom he served at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

which resulted in the capture of Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

.

Settler in America

On April 16, 1762, he resigned his commission, and, in 1764, he settled in Ligonier Valley, Pennsylvania, where he purchased land and erected mills. He was the largest landowner inWestern Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania is a region in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, covering the western third of the state. Pittsburgh is the region's principal city, with a metropolitan area population of about 2.4 million people, and serves as its economic ...

.

In 1770, St. Clair became a justice of the court, of quarter sessions and of common pleas, a member of the proprietary council, a justice, recorder, and clerk of the orphans' court, and prothonotary

The word prothonotary is recorded in English since 1447, as "principal clerk of a court," from L.L. ''prothonotarius'' ( c. 400), from Greek ''protonotarios'' "first scribe," originally the chief of the college of recorders of the court of the B ...

of Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

and Westmoreland counties.

In 1774, the colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

took claim of the area around Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania, and some residents of Western Pennsylvania took up arms to eject them. St. Clair issued an order for the arrest of the officer leading the Virginia troops. Lord Dunmore's War

Lord Dunmore's War—or Dunmore's War—was a 1774 conflict between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations.

The Governor of Virginia during the conflict was John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore—Lord Dunmore. H ...

eventually settled the boundary dispute.

Revolutionary War

By the mid-1770s, St. Clair considered himself more of an American than a British subject. In January 1776, he accepted a commission in theContinental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of the 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment

The 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment, first known as the 2nd Pennsylvania Battalion, was raised on December 9, 1775, at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for service with the Continental Army. The regiment would see action during the Battle of Valcour Island ...

. He first saw service in the later days of the Quebec invasion, where he saw action in the Battle of Trois-Rivières

The Battle of Trois-Rivières was fought on June 8, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. A British army under Quebec Governor Guy Carleton defeated an attempt by units from the Continental Army under the command of Brigadier General Wi ...

. He was appointed a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in August 1776, and was sent by Gen. George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

to help organize the New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

militia. He took part in George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River

George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River occurred on the night of December 25–26, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, was the first move in a surprise attack organized by George Washington against Hessian forces, whic ...

on the night of December 25–26, 1776, before the Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton was a small but pivotal American Revolutionary War battle on the morning of December 26, 1776, in Trenton, New Jersey. After General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American m ...

on the morning of December 26. Many biographers credit St. Clair with the strategy that led to Washington's capture of Princeton, New Jersey, on January 3, 1777. St. Clair was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

in February 1777.

In April 1777, St. Clair was sent to defend Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French mi ...

. His outnumbered garrison could not resist British General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several batt ...

's larger force in the Saratoga campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British high command for North America to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of the British ...

. St. Clair was forced to retreat at the Siege of Fort Ticonderoga on July 5, 1777. He withdrew his forces and played no further part in the campaign. In 1778 he was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed for the loss of Ticonderoga. The court exonerated him and he returned to duty, although he was no longer given any battlefield commands. He still saw action, however, as an aide-de-camp to General Washington, who retained a high opinion of him. St. Clair was at Yorktown when Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

surrendered his army. During his military service, St. Clair was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1780.

President of the United States in Congress Assembled

St. Clair was a member of the Pennsylvania Council of Censors in 1783, and was elected a delegate to theConfederation Congress

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Marc ...

, serving from November 2, 1785, until November 28, 1787. Chaos ruled the day in early 1787 with Shays's Rebellion

Shays Rebellion was an armed uprising in Western Massachusetts and Worcester in response to a debt crisis among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes both on individuals and their trades. The ...

in full force and the states refusing to settle land disputes or contribute to the now six-year-old federal government. On February 2, 1787, the delegates finally gathered into a quorum and elected St. Clair to a one-year term as President of the Continental Congress

The president of the United States in Congress Assembled, known unofficially as the president of the Continental Congress and later as the president of the Congress of the Confederation, was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress, the ...

. Congress enacted its most important piece of legislation, the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

, during St. Clair's tenure as president. Time was running out for the Confederation Congress, however; during St. Clair's presidency, the Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

was drafting a new United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

, which would abolish the old Congress.

Northwest Territory

Under the

Under the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

of 1787, which created the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, General St. Clair was appointed governor of what is now Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

, along with parts of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

. He named Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Ohio, after the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

, and it was there that he established his home.

As Governor, he formulated Maxwell's Code (named after its printer, William Maxwell), the first written laws of the territory. He also sought to end Native American claims to Ohio land and clear the way for white settlement. In 1789, he succeeded in getting certain Native Americans to sign the Treaty of Fort Harmar

The Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789) was an agreement between the United States government and numerous Native American tribes with claims to the Northwest Territory.

History

The Treaty of Fort Harmar was signed at Fort Harmar, near present-day M ...

, but many native leaders had not been invited to participate in the negotiations, or had refused to do so. Rather than settling the Native Americans' claims, the treaty provoked them to further resistance in what is also sometimes known as the "Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

" (or "Little Turtle's War"). Mutual hostilities led to a campaign by General Josiah Harmar

Josiah Harmar (November 10, 1753August 20, 1813) was an officer in the United States Army during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War. He was the senior officer in the Army for six years and seven months (August 1784 to Ma ...

, whose 1,500 militiamen were defeated by the Native Americans in October 1790.

In March 1791, St. Clair succeeded Harmar as commander of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

and was commissioned as a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

. He personally led a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong behavio ...

involving two Regular Army regiments and some militia. In October 1791 as an advance post for his campaign, Fort Jefferson (Ohio)

Fort Jefferson was a fortification erected by soldiers of the United States Army in October 1791 during the Northwest Indian War. Built to support a military campaign, it saw several years of active fighting. Today, the fort site is a historic ...

was built under the direction of General Arthur St. Clair. Located in present-day Darke County

Darke County is a county in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 51,881. Its county seat is Greenville. The county was created in 1809 and later organized in 1817. It is named for William Darke, an officer in the ...

in far western Ohio, the fort was built of wood and intended primarily as a supply depot; accordingly, it was originally named Fort Deposit.

One month later, near modern-day Fort Recovery

Fort Recovery was a United States Army fort ordered built by General "Mad" Anthony Wayne during what is now termed the Northwest Indian War. Constructed from late 1793 and completed in March 1794, the fort was built along the Wabash River, with ...

, his force advanced to the location of Native American settlements near the headwaters of the Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

, but on November 4 they were routed in battle by a tribal confederation led by Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

Chief Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

and Shawnee chief Blue Jacket

Blue Jacket, or Weyapiersenwah (c. 1743 – 1810), was a war chief of the Shawnee people, known for his militant defense of Shawnee lands in the Ohio Country. Perhaps the preeminent American Indian leader in the Northwest Indian War, i ...

. They were aided by British collaborators Alexander McKee

Alexander McKee ( – 15 January 1799) was an American-born military officer and colonial official in the British Indian Department during the French and Indian War, the American Revolutionary War, and the Northwest Indian War. He achieved the ...

and Simon Girty

Simon Girty (November 14, 1741 – February 18, 1818) was an American-born frontiersman, soldier and interpreter from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who served as a liaison between the British and their Indian allies during the American Revolution. H ...

. More than 600 soldiers and scores of women and children were killed in the battle, which has since borne the name " St. Clair's Defeat", also known as the "Battle of the Wabash", the "Columbia Massacre," or the "Battle of a Thousand Slain". It remains the greatest defeat of a US Army by Native Americans in history, with about 623 American soldiers killed in action and about 50 Native Americans killed. The wounded were many, including St. Clair and Capt. Robert Benham.

Although an investigation exonerated him, St. Clair resigned his army commission in March 1792 at the request of President Washington, but he continued to serve as Governor of the Northwest Territory.

A

A Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

, St. Clair hoped to see two states made of the Ohio Territory in order to increase Federalist power in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

. However, he was opposed by Ohio Democratic-Republicans for what were perceived as his partisanship, high-handedness, and arrogance in office. In 1802, St. Clair remarked the U.S. Congress had no power to interfere in the affairs of those in the Ohio Territory. He also stated the people of the territory "are no more bound by an act of Congress than we would be bound by an edict of the first consul of France." This led President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

to remove him from office as territorial governor. He thus played no part in the organizing of the state of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

in 1803.

The first Ohio Constitution

The Constitution of the State of Ohio is the basic governing document of the State of Ohio, which in 1803 became the 17th state to join the United States of America. Ohio has had three constitutions since statehood was granted.

Ohio was create ...

provided for a weak governor and a strong legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

, in part as a reaction to St. Clair's method of governance.

Family life

St. Clair met Phoebe Bayard, a member of one of the most prominent families in Boston, and they were married in 1760. Miss Bayard's mother's maiden name was Bowdoin and she was the sister ofJames Bowdoin

James Bowdoin II (; August 7, 1726 – November 6, 1790) was an American political and intellectual leader from Boston, Massachusetts, during the American Revolution and the following decade. He initially gained fame and influence as a wealthy ...

, colonial governor of Massachusetts.

His eldest daughter was Louisa St. Clair Robb, a mounted messenger and scout, and known as a beautiful huntress.

Like many of his Revolutionary era peers, St. Clair suffered from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

as noted in correspondence with John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

.

Death

In retirement St. Clair lived with his daughter, Louisa St. Clair Robb, and her family on the ridge between Ligonier and Greensburg. Arthur St. Clair died in poverty in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, on August 31, 1818, at the age of 81. His remains are buried under a Masonic monument in St. Clair Park in downtown Greensburg. St. Clair had been a petitioner for a Charter for Nova Caesarea Lodge #10 in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1791. This Lodge exists today, as Nova Caesarea Harmony #2. His wife Phoebe died shortly after and is buried beside him.Legacy

A portion of the Hermitage, St. Clair's home in Oak Grove, Pennsylvania (north of Ligonier), was later moved to Ligonier, Pennsylvania, where it is now preserved, along with St. Clair artifacts and memorabilia at theFort Ligonier

Fort Ligonier is a British fortification from the French and Indian War located in Ligonier, Pennsylvania, United States. The fort served as a staging area for the Forbes Expedition of 1758. During the eight years of its existence as a garrison, F ...

Museum.

An American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

steamer was named USS ''St. Clair''.

Lydia Sigourney

Lydia Huntley Sigourney (September 1, 1791 – June 10, 1865), ''née'' Lydia Howard Huntley, was an American poet, author, and publisher during the early and mid 19th century. She was commonly known as the "Sweet Singer of Hartford." She had a ...

included a poem in his honor, in her first poetry collection of 1815.

The site of Clair's inauguration as Governor of the Northwest Territory is now occupied by the '' National Start Westward Memorial of The United States'', commemorating the settlement of the territory.

Places named in honor of Arthur St. Clair include:

In Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

:

* Upper St. Clair, Pennsylvania

* St. Clairsville, Pennsylvania

* St. Clair Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania

* St. Clair Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania

* East St. Clair Township, Bedford County, Pennsylvania

* West St. Clair Township, Bedford County, Pennsylvania

* The St. Clair neighborhood in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania

* St. Clair Hospital, Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania

In Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

:

*St. Clair Township in Butler County, Ohio

* St. Clair Township in Columbiana County

Columbiana County is a County (United States), county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 101,877. The county seat is Lisbon, Ohio, Lisbon and its largest city is Salem, Ohio, ...

, Ohio,

* St. Clairsville, Ohio

* St. Clair Avenue in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Ohio

* St. Clair Street in Dayton

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Da ...

, Ohio

* St. Clair Street in Toledo, Ohio

* Fort St. Clair in Eaton, Ohio

Other States:

* St. Clair County, Illinois

* St. Clair Street in Indianapolis, Indiana

* St. Clair County, Missouri

* St. Clair County, Alabama

* St. Clair Street in Frankfort, Kentucky, was named for the St. Clair by Gen. James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, b ...

, who laid out the town that became the state capital

Below is an index of pages containing lists of capital cities.

National capitals

*List of national capitals

*List of national capitals by latitude

*List of national capitals by population

*List of national capitals by area

*List of capital citie ...

. The street's north end is at the Old Capitol, and near its south end is the Franklin County Court House; both were designed by Gideon Shryock

Gideon Shryock (November 15, 1802 – June 19, 1880) was Kentucky's first professional architect in the Greek Revival Style. His name has frequently been misspelled as Gideon Shyrock.

Biography

Shryock was born in Lexington, Kentucky on Novembe ...

.

In Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

:

* The three-star St Clair Hotel in Sinclair St, Thurso

Thurso (pronounced ; sco, Thursa, gd, Inbhir Theòrsa ) is a town and former burgh on the north coast of the Highland council area of Scotland. Situated in the historical County of Caithness, it is the northernmost town on the island of Great ...

, Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded by ...

, is named after him.

References

Notes Books * Kopper, Kevin Patrick. "Arthur St. Clair and the Struggle For Power in the Old Northwest, 1763–1803" (Dissertation. Kent State University, 2005online

* *

External links

Ohio Memory

Ohio History Central

The Hermitage – home of Arthur St. Clair

{{DEFAULTSORT:St. Clair, Arthur 1737 births 1818 deaths Adjutants general of the United States Army Continental Army generals Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania Continental Army personnel who were court-martialed Continental Congressmen from Pennsylvania 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians Governors of Northwest Territory Politicians from Cincinnati People from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania American people of the Northwest Indian War Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British military personnel of the French and Indian War People from Thurso Royal American Regiment officers British emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies Commanding Generals of the United States Army