Repatriation is the return of the

cultural property

Cultural property does not have a universal definition, but it is commonly considered to be tangible (physical, material) items that are part of the cultural heritage of a group or society, as opposed to less tangible cultural expressions. They i ...

, often referring to ancient or

looted art

Looted art has been a consequence of looting during war, natural disaster and riot for centuries. Looting of art, archaeology and other cultural property may be an opportunistic criminal act or may be a more organized case of unlawful or unet ...

, to their country of origin or former owners (or their heirs). The disputed cultural property items are physical artifacts of a group or society taken by another group, usually in the act of looting, whether in the context of

imperialism,

colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

, or

war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

. The contested objects vary widely and include

sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable ...

s,

paintings

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ai ...

,

monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

s, objects such as

tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

s or

weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, ...

s for purposes of

anthropological study, and

human remains.

The looting of defeated peoples' cultural heritage by war has been common practice since ancient times. In the modern era, the

Napoleonic looting of art was a series of confiscations of artworks and precious objects carried out by the French army or French officials in the territories of the

First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

, including the

Italian peninsula, Spain, Portugal, the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, and Central Europe. The looting continued for nearly 20 years, from 1797 to the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815.

After Napoleon's defeat, some of the

looted artworks were returned to their country of origin, among them the

Lion and the

Horses of Saint Mark

The Horses of Saint Mark ( it, Cavalli di San Marco), also known as the Triumphal Quadriga or Horses of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, is a set of bronze statues of four horses, originally part of a monument depicting a quadriga (a four-hor ...

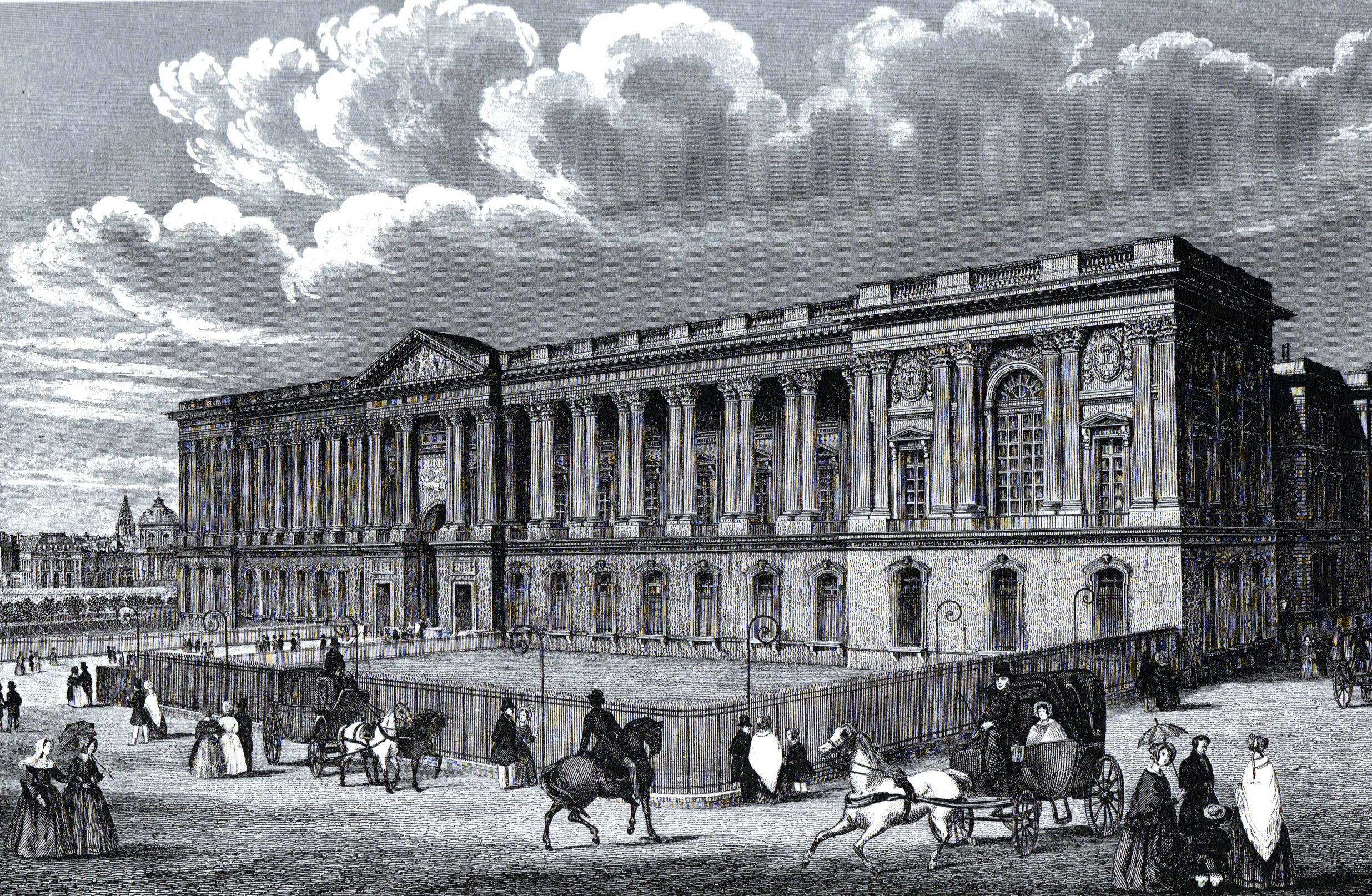

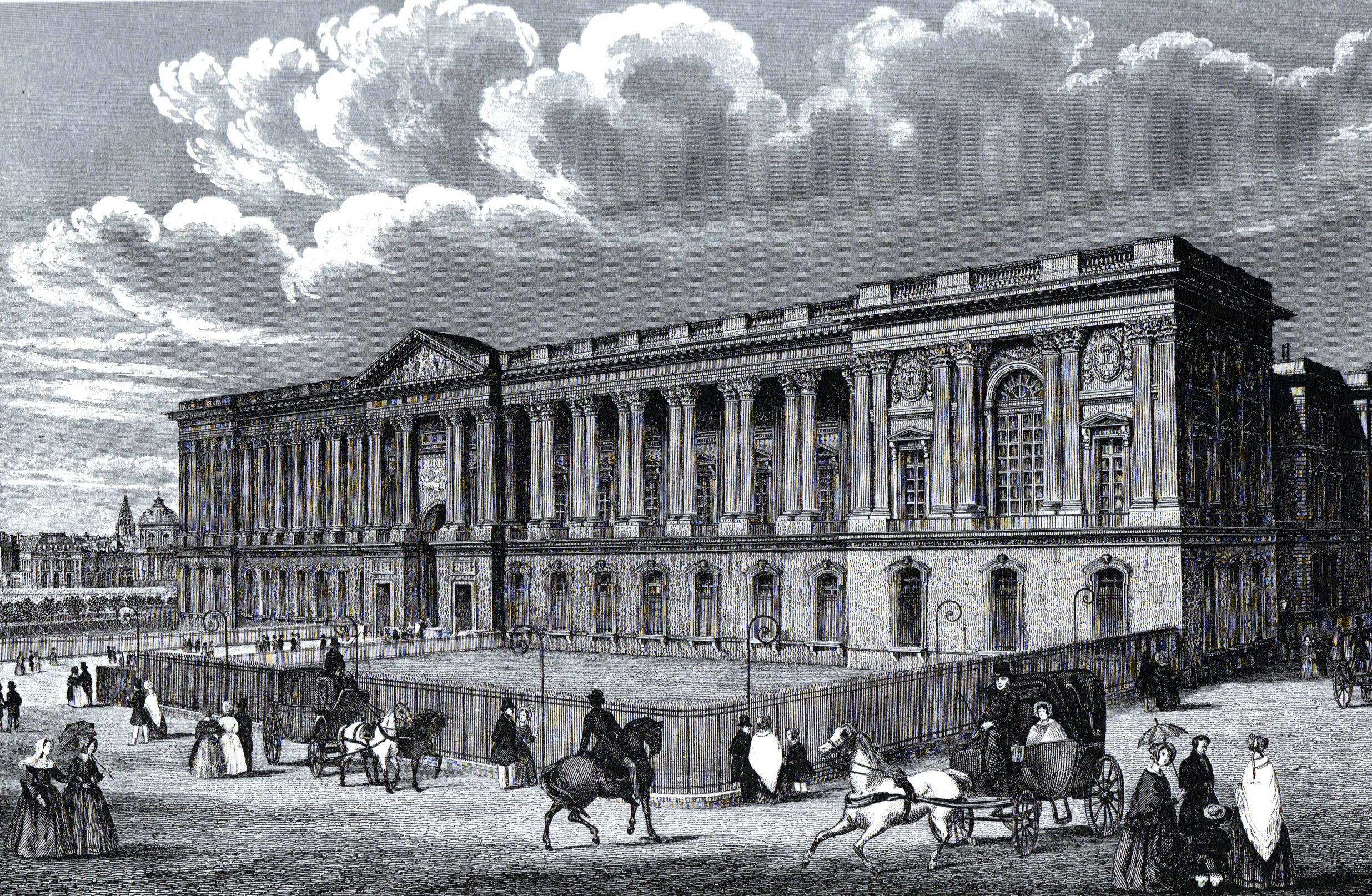

, that were repatriated to Venice. But many other artworks remained in French museums, like the

Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

museum, the

Bibliothèque Nationale

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

in Paris or other collections in France.

In the early 21st century, debates about the colonial context of acquisitions by Western collections have centered both around arguments against and in favor of repatriations. Since the publication of the French

report on the restitution of African cultural heritage

''The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics'' (in French: ''Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle'') is a report written by Senegalese academic and ...

in 2018, these debates have gained new international attention and have led to changes regarding the public role of museums and to restitutions on moral rather than merely legal grounds.

Background

War and looting

Ancient world

War and the subsequent looting of defeated peoples have been common practice since ancient times. The stele of King

Naram-Sin of Akkad

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen ( akk, : '' DNa-ra-am D Sîn'', meaning "Beloved of the Moon God Sîn", the "𒀭" being a silent honorific for "Divine"), was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254–2218 BC ...

, which is now displayed in the Louvre Museum in Paris, is one of the earliest works of art known to have been looted in war. The stele commemorating Naram-Sin's victory in a battle against the

Lullubi

Lullubi, Lulubi ( akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈: ''Lu-lu-bi'', akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠: ''Lu-lu-biki'' "Country of the Lullubi"), more commonly known as Lullu, were a group of tribes during the 3rd millennium BC, from a region known as ''Lulubum'', now the Sha ...

people in 2250 BCE was taken as war plunder about a thousand years later by the

Elamites who relocated it to their capital in

Susa, Iran. There, it was uncovered in 1898 by French archaeologists.

The

Palladion was the earliest and perhaps the most important stolen statue in western literature.

[Miles, p. 20] The small carved wooden statue of an armed

Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded ...

served as Troy's protective

talisman

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

, which is said to have been stolen by two Greeks who secretly smuggled the statue out of the

Temple of Athena. It was widely believed in antiquity that the conquest of Troy was only possible because the city had lost its protective talisman. This myth illustrates the sacramental significance of statuary in Ancient Greece as divine manifestations of the gods that symbolized power and were often believed to possess supernatural abilities. The sacred nature of the statues is further illustrated in the supposed suffering of the victorious Greeks afterward, including

Odysseus, who was the mastermind behind the robbery.

According to Roman myth, Rome was founded by

Romulus, the first victor to dedicate spoils taken from an enemy ruler to the

Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

The Temple of Jupiter Feretrius (Latin: ''Aedes Iuppiter Feretrius'') was, according to legend, the first temple ever built in Rome (the second being the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus). Its site is uncertain but is thought to have been on the ...

. In Rome's many subsequent wars, blood-stained armor and weaponry were gathered and placed in temples as a symbol of respect toward the enemies' deities and as a way to win their patronage.

[Miles, p. 13] As Roman power spread throughout Italy where Greek cities once reigned, Greek art was looted and ostentatiously displayed in Rome as a triumphal symbol of foreign territories brought under Roman rule.

However, the triumphal procession of

Marcus Claudius Marcellus

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (; 270 – 208 BC), five times elected as consul of the Roman Republic, was an important Roman military leader during the Gallic War of 225 BC and the Second Punic War. Marcellus gained the most prestigious award a Roma ...

after the fall of Syracuse in 211 is believed to have set a standard of reverence to conquered sanctuaries as it engendered disapproval by critics and a negative social reaction.

According to

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, the

Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

was sufficiently embarrassed by the history of Roman plunder of Greek art to return some pieces to their original homes.

A precedent for art repatriation was set in Roman antiquity when

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

prosecuted

Verres

Gaius Verres (c. 120–43 BC) was a Roman magistrate, notorious for his misgovernment of Sicily. His extortion of local farmers and plundering of temples led to his prosecution by Cicero, whose accusations were so devastating that his defence adv ...

, a senate member and illegal appropriator of art. Cicero's speech influenced

Enlightenment European thought and had an indirect impact on the modern debate about art repatriation. Cicero's argument uses military episodes of plunder as "case law" and expresses certain standards when it comes to appropriating cultural property of another people. Cicero makes a distinction between public and private uses of art and what is appropriate for each and he also asserts that the primary purpose of art is religious expression and veneration. He also sets standards for the responsibilities of imperial administration abroad to the code of ethics surrounding the collection of art from defeated Greece and Rome in wartime. Later, both Napoleon and Lord Elgin would be likened to Verres in condemnations of their plundering of art.

Looting during Napoleon's Empire

The scale of

plundering during Napoleon's French Empire was unprecedented in modern history with the only comparable looting expeditions taking place in ancient Roman history. In fact, the French revolutionaries justified the large-scale and systematic looting of Italy in 1796 by viewing themselves as the political successors of Rome, in the same way that ancient Romans saw themselves as the heirs of Greek civilization.

[Miles, p. 320] They also supported their actions with the opinion that their sophisticated artistic taste would allow them to appreciate the plundered art. Napoleon's soldiers crudely dismantled the art by tearing paintings out of their frames hung in churches and sometimes causing damage during the shipping process. Napoleon's soldiers appropriated private collections and even the papal collection.

[Miles, p. 321] The most famous artworks plundered included the

Bronze Horses of Saint Mark in Venice (itself loot from the

Sack of Constantinople

The sack of Constantinople occurred in April 1204 and marked the culmination of the Fourth Crusade. Crusader armies captured, looted, and destroyed parts of Constantinople, then the capital of the Byzantine Empire. After the capture of the ...

in 1204) and the

Laocoön and His Sons

The statue of ''Laocoön and His Sons'', also called the Laocoön Group ( it, Gruppo del Laocoonte), has been one of the most famous ancient sculptures ever since it was excavated in Rome in 1506 and placed on public display in the Vatican Museums ...

in Rome (both since returned), with the latter being considered the most impressive sculpture from antiquity at the time.

The Laocoön had a particular meaning for the French because it was associated with a myth in connection to the founding of Rome. When the art was brought into Paris, the pieces arrived in the fashion of a triumphal procession modeled after the common practice of ancient Romans.

Napoleon's extensive plunder of Italy was criticized by such French artists as

Antoine-Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy (1755–1849), who circulated a petition that gathered the signatures of fifty other artists. With the founding of the

Louvre Museum

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

in Paris in 1793, Napoleon's aim was to establish an encyclopedic exhibition of art history, which later both

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

and

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

would attempt to emulate in their respective countries.

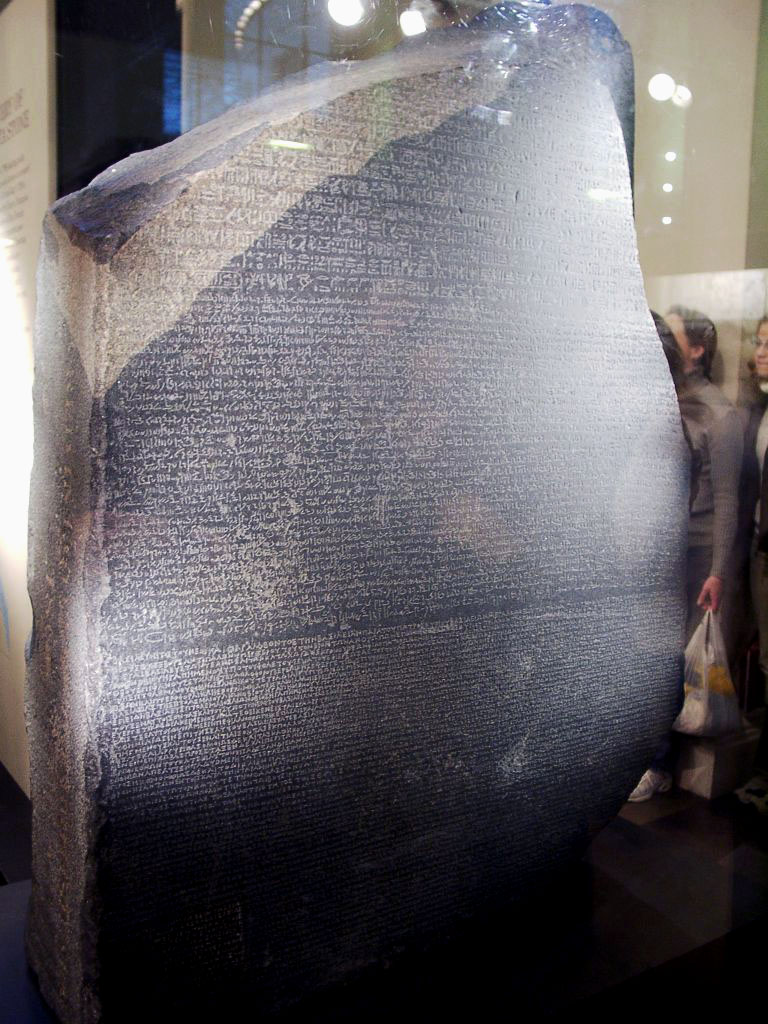

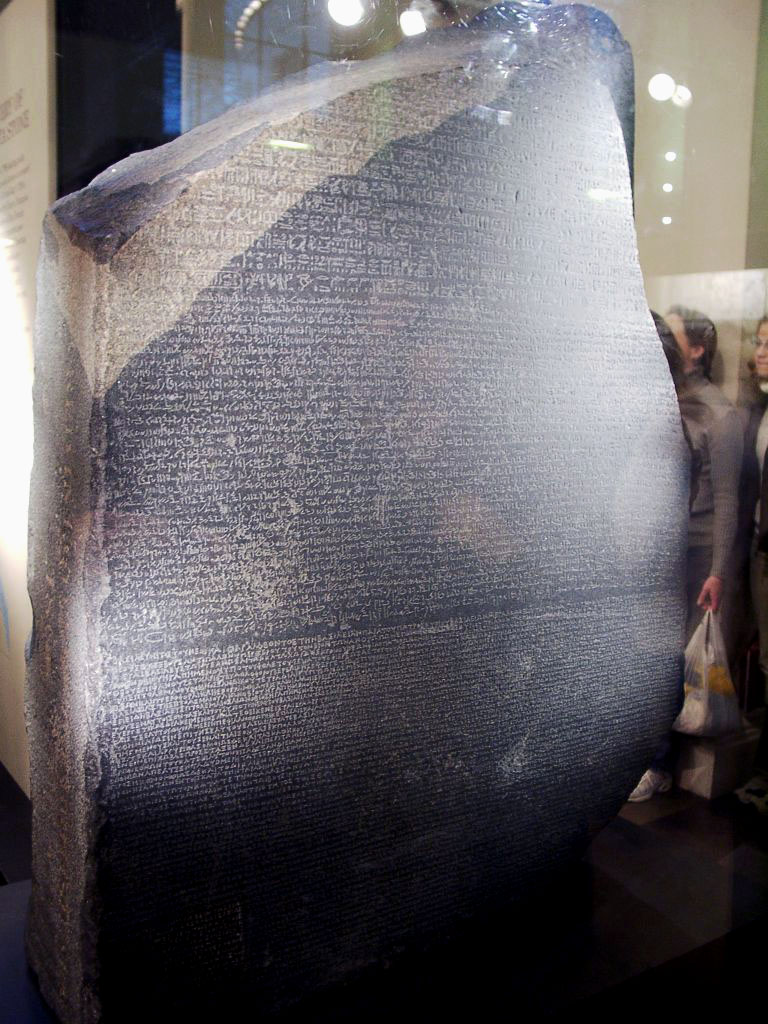

Napoleon continued his art conquests in 1798 when he invaded Egypt in an attempt to safeguard French trade interests and to undermine Britain's access to India via Egypt. His expedition in Egypt is noted for the 167 "savants" he took with him including scientists and other specialists equipped with tools for recording, surveying and documenting ancient and modern Egypt and its natural history. Among other things, the expedition discoveries included the

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancien ...

and the

Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings ( ar, وادي الملوك ; Late Coptic: ), also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings ( ar, وادي أبوا الملوك ), is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th ...

near Thebes. The French military campaign was short-lived and unsuccessful and the majority of the collected artifacts (including the Rosetta Stone) were seized by British troops, ending up in the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. Nonetheless, the information gathered by the French expedition was soon after published in the several volumes of ''

Description de l'Égypte

The ''Description de l'Égypte'' ( en, Description of Egypt) was a series of publications, appearing first in 1809 and continuing until the final volume appeared in 1829, which aimed to comprehensively catalog all known aspects of ancient and m ...

'', which included 837 copperplate engravings and over 3,000 drawings. In contrast to the disapproving public reaction to the looting of Italian works of art, the appropriation of Egyptian art saw widespread interest and fascination throughout Europe, inciting a phenomenon which came to be called "

Egyptomania

Egyptomania refers to a period of renewed interest in the culture of ancient Egypt sparked by Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign in the 19th century. Napoleon was accompanied by many scientists and scholars during this Campaign, which led to a large ...

".

[Miles, p. 329]

A notable consequence of looting is its ability to hinder contemporary repatriation claims of cultural property to a country or community of origin. A process that requires proof of theft of an illegal transaction, or that the object originated from a specific country, can be difficult to provide if the looting and subsequent movements or transactions were undocumented.

For example, in 1994 the British Library acquired

Kharosthi manuscript fragments and has since refused to return them unless their origin could be identified (Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Tajikistan), of which the library itself was unsure.

Repatriation after the Napoleonic Wars

Art was repatriated for the first time in modern history when

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish soldier and Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of Uni ...

returned to Italy art that had been plundered by Napoleon, after his and Marshal Blücher's armies defeated the French at the

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

in 1815.

This decision contrasted sharply to a long-held tradition to the effect that "

to the victors go the spoils."

This is remarkable considering that in the battle of Waterloo alone, the financial and human costs were colossal; the decision to not only refrain from plundering France but to repatriate France's prior seizures from the Netherlands, Italy, Prussia, and Spain, was extraordinary. Moreover, the British paid for the restitution of the papal collection to Rome because the Pope could not finance the shipping himself. When British troops began packing up looted art from the Louvre, there was a public outcry in France. Crowds reportedly tried to prevent the taking of the

Horses of Saint Mark

The Horses of Saint Mark ( it, Cavalli di San Marco), also known as the Triumphal Quadriga or Horses of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, is a set of bronze statues of four horses, originally part of a monument depicting a quadriga (a four-hor ...

and there were throngs of weeping ladies outside the Louvre Museum.

[Miles, p. 334] Despite the unprecedented nature of this repatriation effort, there are recent estimations that only about 55 percent of what was taken was actually repatriated: the Louvre Director at the time,

Vivant Denon

Dominique Vivant, Baron Denon (4 January 1747 – 27 April 1825) was a French artist, writer, diplomat, author, and archaeologist. Denon was a diplomat for France under Louis XV and Louis XVI. He was appointed as the first Director of the Louvre ...

, had sent out many important works to other parts of France before the British could take them. Wellington viewed himself as representing all of Europe's nations and he believed that the moral decision would be to restore the art in its apparently proper context. In a letter to

Lord Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, (18 June 1769 – 12 August 1822), usually known as Lord Castlereagh, derived from the courtesy title Viscount Castlereagh ( ) by which he was styled from 1796 to 1821, was an Anglo-Irish politician ...

he wrote:

Wellington also forbade pilfering among his troops as he believed that it led to the lack of discipline and distraction from military duty. He also held the view that winning support from local inhabitants was an important break from Napoleon's practices.

The great public interest in art repatriation helped fuel the expansion of public museums in Europe and launched museum-funded archaeological explorations. The concept of art and cultural repatriation gained momentum through the latter decades of the twentieth century and began to show fruition by the end of the century when key works were ceded back to claimants.

20th and 21st centuries

Looting by Germany during the Nazi era

One of the most infamous cases of esurient art plundering in wartime was the

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

appropriation of art from both public and private holdings throughout Europe and Russia. The looting began before

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

with illegal seizures as part of a systematic persecution of Jews, which was included as a part of Nazi crimes during the

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

. During World War II, Germany plundered 427 museums in the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and ravaged or destroyed 1,670

Russian Orthodox

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: Русское православие) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

churches, 237

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

churches and 532 synagogues.

Looting in Iraq after the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime

A well-known recent case of wartime looting was the plundering of ancient artifacts from the

National Museum of Iraq

The Iraq Museum ( ar, المتحف العراقي) is the national museum of Iraq, located in Baghdad. It is sometimes informally called the National Museum of Iraq, a recent phenomenon influenced by other nations' naming of their national museum ...

in Baghdad at the outbreak of the war in 2003. Although this was not a case in which the victors plundered art from their defeated enemy, it was result of the unstable and chaotic conditions of war that allowed looting to happen and which some would argue was the fault of the invading US forces.

Archaeologists and scholars criticized the US military for not taking the measures to secure the museum, a repository for a myriad of valuable ancient artifacts from the ancient

Mesopotamian civilization. In the several months leading up to the war, scholars, art directors, and collector met with

the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a meton ...

to ensure that the US government would protect Iraq's important archaeological heritage, with the National Museum in Baghdad being at the top of the list of concerns.

[Greenfield, p. 263] Between April 8, when the museum was vacated and April 12, when some of the staff returned, an estimated 15,000 items and an additional 5,000 cylinder seals were stolen.

Moreover, the National Library was plundered of thousands of

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sh ...

tablets and the building was set on fire with half a million books inside; fortunately, many of the manuscripts and books were preserved.

A US task force was able to retrieve about half of the stolen artifacts by organizing and dispatching an inventory of missing objects and by declaring that there would be no punishment for anyone returning an item.

In addition to the vulnerability of art and historical institutions during the Iraq war, Iraq's rich archaeological sites and areas of excavated land (Iraq is presumed to possess vast undiscovered treasures) have fallen victim to widespread looting.

[Greenfield, p. 268] Hordes of looters disinterred enormous craters around Iraq's archaeological sites, sometimes using bulldozers. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 archaeological sites in Iraq have been despoiled.

Legal issues

National government laws

United States

In 1863 US President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

summoned

Francis Lieber

Francis Lieber (March 18, 1798 or 1800 – October 2, 1872), known as Franz Lieber in Germany, was a German-American jurist, gymnast and political philosopher. He edited an '' Encyclopaedia Americana''. He was the author of the Lieber Code duri ...

, a German-American jurist and political philosopher, to write a legal code to regulate Union soldiers' behavior toward Confederate prisoners, noncombatants, spies and property. The resulting ''General Orders No.100'' or the

Lieber Code

The Lieber Code of April 24, 1863, issued as General Orders No. 100, Adjutant General's Office, 1863, was an instruction signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln to the Union forces of the United States during the American Civil War that dictated h ...

, legally recognized cultural property as a protected category in war. The Lieber Code had far-reaching results as it became the basis for the Hague Convention of 1907 and 1954 and has led to Standing Rules of Engagement (ROE) for US troops today.

[Miles, p. 352] A portion of the ROE clauses instruct US troops not to attack "schools, museums, national monuments, and any other historical or cultural sites unless they are being used for a military purpose and pose a threat".

In 2004 the US passed the Bill HR1047 for the Emergency Protection for Iraq Cultural Antiquities Act, which allows the President authority to impose emergency import restrictions by Section 204 of the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCIPA). In 2003, Britain and Switzerland put into effect statutory prohibitions against illegally exported Iraqi artifacts. In the UK, the Dealing in Cultural Objects Bill was established in 2003 that prohibited the handling of illegal cultural objects.

United Kingdom

Repatriation in the UK has been highly debated in recent years, however there is still a lack of formal national legislation that expressly outlines general claims and repatriation procedures.

As a result, guidance on repatriation stems from museum authority and government guidelines, such as the

Museum Ethnographers' Group (1994) and the

Museums Association Guidelines on Restitution and Repatriation (2000). This means that individual museum policies on repatriation can vary significantly depending on the museum's views, collections and other factors.

The repatriation of human remains is governed by the

Human Tissue Act 2004

The Human Tissue Act 2004 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, that applied to England, Northern Ireland and Wales, which consolidated previous legislation and created the Human Tissue Authority to "regulate the removal, storage, u ...

. However, the Act itself does not create guidelines on the process of repatriation, it merely states it is legally possible for museums to do so.

This again highlights that successful repatriation claims in the UK are dependent on museum policy and procedure. One example includes the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

's policy on the restitution of human remains.

International conventions

The Hague Convention of 1907 aimed to forbid pillaging and sought to make wartime plunder the subject of legal proceedings, although in practice the defeated countries did not gain any leverage in their demands for repatriation.

The Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict took place in the wake of widespread destruction of cultural heritage in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and is the first international treaty of a worldwide vocation focusing exclusively on the protection of cultural heritage in the event of armed conflict.

Irini Stamatoudi suggests that the 1970 UNESCO convention on prohibiting and preventing illicit imports and exports and the 1995 UNIDROIT convention on stolen or illegally exported cultural objects are the most important international conventions related to cultural property law.

UNESCO

The

1970 UNESCO Convention against Illicit Export under the Act to implement the convention (the Cultural Property Implementation Act) allowed for stolen objects to be seized, if there were documentation of it in a museum or institution of a state party, the convention also encouraged member states to adopt the convention within their own national laws. The following agreement in 1972 promoted world cultural and natural heritage.

The 1978 UNESCO Convention strengthened existing provisions; the Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its countries of origin or its restitution in case of illicit appropriation was established. It consists of 22 members elected by the General Conference of UNESCO to facilitate bilateral negotiations for the restitution of "any cultural property which has a fundamental significance from the point of view of the spiritual values and cultural heritage of the people of a Member State or Associate Member of UNESCO and which has been lost as a result of colonial or foreign occupation or as a result of illicit appropriation".

It was also created to "encourage the necessary research and studies for the establishment of coherent programmes for the constitution of representative collections in countries, whose cultural heritage has been dispersed".

In response to the

Iraqi National Museum looting, UNESCO Director-General,

Kōichirō Matsuura

is a Japanese diplomat. He is the former Director-General of UNESCO. He was first elected in 1999 to a six-year term and reelected on 12 October 2005 for four years, following a reform instituted by the 29th session of the General Conference. In ...

convened a meeting in Paris on April 17, 2003, to assess the situation and coordinate international networks in order to recover the cultural heritage of Iraq. On July 8, 2003,

Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an international organization that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and cri ...

and UNESCO signed an amendment to their 1999 Cooperation Agreement in the effort to recover looted Iraqi artifacts.

UNIDROIT

The

UNIDROIT

UNIDROIT (formally, the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law; French: ''Institut international pour l'unification du droit privé'') is an intergovernmental organization whose objective is to harmonize international privat ...

(International Institute for the Unification of Private Law) Convention on Stolen or Illicitly Exported Cultural Objects of 1995 called for the return of illegally exported cultural objects.

Cultural heritage in international contexts

Colonialism and identity

From early on, the field of archaeology was deeply involved in political endeavors and in the construction of national identities. This early relationship can be seen during the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

and the proto-Italian reactions against the

High Gothic

High Gothic is a particularly refined and imposing style of Gothic architecture that appeared in northern France from about 1195 until 1250. Notable examples include Chartres Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and ...

movement, but the relationship became stronger during 19th century Europe when archaeology became institutionalized as a field of study furnished by artifacts acquired during the

New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

era of

European colonialism. Colonialism and the field of archaeology mutually supported one another as the need to acquire knowledge of ancient artifacts justified further colonial dominance.

As further justification for colonial rule, the archaeological discoveries also shaped the way European colonialists identified with the artifacts and the ancient people who made them. In the case of Egypt, colonial Europe's mission was to bring the glory and magnificence of ancient Egypt closer to Europe and incorporate it into knowledge of world history, or better yet, use European history to place ancient Egypt in a new spotlight. With the archaeological discoveries, ancient Egypt was adopted into the Western historical narrative and came to take on a significance that had up until that time been reserved for ancient Greek and Roman civilization.

[Colla 103] The French revolutionaries justified the large-scale and systematic looting of Italy in 1796 by viewing themselves as the political successors of Rome, in the same way that ancient Romans saw themselves as the heirs of Greek civilization; by the same token, the appropriation of ancient Egyptian history as European history further legitimated Western colonial rule over Egypt. But while ancient Egypt became patrimony of the West, modern Egypt remained a part of the Muslim world.

The writings of European archaeologists and tourists illustrate the impression that modern Egyptians were uncivilized, savage, and the antithesis of the splendor of ancient Egypt.

Museums furnished by colonial looting have largely shaped the way a nation imagines its dominion, the nature of the human beings under its power, the geography of the land, and the legitimacy of its ancestors, working to suggest a process of political inheriting. It is necessary to understand the paradoxical way in which the objects on display at museums are tangible reminders of the power held by those who gaze at them. Eliot Colla describes the structure of the Egyptian sculpture room in the British Museum as an assemblage that "form

an abstract image of the globe with London at the center".

[Colla 5] The

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, as Colla describes, presents a lesson of human development and progress: "the forward march of human civilization from its classical origins in Greece and Rome, through Renaissance Italy, to modern-day London".

The restoration of monuments was often made in colonial states to make natives feel as if in their current state, they were no longer capable of greatness.

[Anderson 181] Furthermore, sometimes colonial rulers argued that the ancestors of the colonized people did not make the artifacts.

Some scholars also argue that European colonialists used monumental archaeology and tourism to appear as the guardian of the colonized, reinforcing unconscious and undetectable ownership.

Colonial rulers used peoples, religions, languages, artifacts, and monuments as source for reinforcing European nationalism, which was adopted and easily inherited from the colonial states.

Nationalism and identity

As a direct reaction and resistance to colonial oppression, archaeology was also used for the purpose of legitimating the existence of an independent nation-state. For example, Egyptian Nationalists utilized its ancient history to invent the political and expressive culture of "

Pharaonism" as a response to Europe's "

Egyptomania

Egyptomania refers to a period of renewed interest in the culture of ancient Egypt sparked by Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign in the 19th century. Napoleon was accompanied by many scientists and scholars during this Campaign, which led to a large ...

".

[Colla 12]

Some argue that in colonized states, nationalist archaeology was used to resist colonialism and racism under the guise of evolution. While it is true that both colonialist and nationalist discourse use the artifact to form mechanisms to sustain their contending political agendas, there is a danger in viewing them interchangeably since the latter was a reaction and form of resistance to the former. On the other hand, it is important to realize that in the process of emulating the mechanisms of colonial discourse, the nationalist discourse produced new forms of power. In the case of the Egyptian nationalist movement, the new form of power and meaning that surrounded the artifact furthered the Egyptian independence cause but continued to oppress the rural Egyptian population.

Some scholars argue that archaeology can be a positive source of pride in cultural traditions, but can also be abused to justify cultural or racial superiority as the Nazis argued that Germanic people of Northern Europe was a distinct race and cradle of Western civilization that was superior to the Jewish race.. In other cases, archaeology allows rulers to justify the domination of neighboring peoples as

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

used

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

's magnificent past to justify his

invasion of Kuwait

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait was an operation conducted by Iraq on 2 August 1990, whereby it invaded the neighboring State of Kuwait, consequently resulting in a seven-month-long Iraqi military occupation of the country. The invasion and Ira ...

in 1990.

Some scholars employ the idea that identity is fluid and constructed, especially national identity of modern nation-states, to argue that the post-colonial countries have no real claims to the artifacts plundered from their borders since their cultural connections to the artifacts are indirect and equivocal. This argument asserts that artifacts should be viewed as universal cultural property and should not be divided among artificially created

nation-states

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

. Moreover, that encyclopedic museums are a testament to diversity, tolerance and the appreciation of many cultures. Other scholars would argue that this reasoning is a continuation of colonialist discourse attempting to appropriate the ancient art of colonized states and incorporate it into the narrative of Western history.

Cultural survival and identity

In

settler-colonial contexts, many Indigenous people that have experienced cultural domination by colonial powers have begun to request the repatriation of objects that are already within the same borders. Objects of

Indigenous cultural heritage, such as ceremonial objects, artistic objects, etc., have ended up in the hands of publicly and privately held collections which were often given up under economic duress, taken during

assimilationist

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's majority group or assume the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group whether fully or partially.

The different types of cultural assi ...

programs or simply stolen.

The objects are often significant to the Indigenous ontologies possessing

animacy and

kinship ties. Objects such as particular instruments used in unique musical traditions, textiles used in spiritual practices or religious carvings have cult significance are connected to the revival of traditional practices. This means that the repatriation of these objects is connected to the cultural survival of Indigenous people historically oppressed by colonialism.

Colonial narratives surrounding "

discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discover ...

" of the new world have historically resulted in Indigenous people's claim to cultural heritage being rejected. Instead, private and public holders have worked towards displaying these objects in museums as a part of colonial national history. Museums often argue that if objects were to be repatriated they would be seldom seen and not properly taken care of. International agreements such as the

1970 UNESCO Convention against Illicit Export under the Act to implement the convention (the Cultural Property Implementation Act) often do not regard Indigenous repatriation claims. Instead, these conventions focus on returning national cultural heritage to states.

Since the 1980s,

decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

efforts have resulted in more museums attempting to work with local Indigenous groups to secure a working relationship and the repatriation of their cultural heritage.

This has resulted in local and international legislation such as

NAGPRA

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990.

The Act requires federal agencies and institutions that ...

and the 1995

which take Indigenous perspectives into consideration in the repatriation process. Notably, Article 12 of

UNDRIP

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP or DOTROIP) is a legally non-binding resolution passed by the United Nations in 2007. It delineates and defines the individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples, including th ...

states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains. States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned.

The process of repatriation has often been fraught with issues though, resulting in the loss or improper repatriation of cultural heritage. The debate between public interest, Indigenous claims and the wrongs of colonialism is the central tension around the repatriation of Indigenous cultural heritage.

Controversies

The repatriation debate

The repatriation debate is a term referring to the dialogue between individuals, heritage institutions, and nations who have possession of cultural property and those who pursue its return to its country or community of origin.

It is suggested that many points within this debate center around the legal issues involved such as theft and the legality of acquisitions and exports, etc.

Two main theories seem to underpin the repatriation debate and cultural property law: cultural nationalism and cultural internationalism.

These theories emerged and developed following the creation of many international conventions, such as the

1970 UNESCO Convention and the

1995 UNIDROIT Convention, and act as the foundation of contradicting opinions regarding the transport of cultural objects.

Cultural internationalism

Cultural internationalism has links to

imperialism and

decontextualization and suggests that cultural property is not tethered to one nation and belongs to everybody. Calls for repatriation can therefore be dismissed since they are often requested when a nation declares ownership of an object,

which according to this theory is not exclusive.

Some critics and even supporters of this theory seek to limit its scope. For example, proponent of cultural internationalism John Henry Merryman suggests that unauthorized archaeological discoveries should not be exported as information would be lost that would have remained intact if they stayed where they were discovered.

It is further argued that this theory has close resemblance to the 'universal museums' theory.

Following a series of repatriation claims, leading museums issued a declaration detailing the importance of the universal museum. The declaration argues that over time, objects acquired by the museums have become part of the heritage of that nation and that museums work to serve people from every country as "agents in the development of culture". It is on this justification that many repatriation requests are denied.

A notable example includes the Greek Parthenon marbles housed at the British Museum.

Many of the issues surrounding the denial of repatriation requests originate from items taken during the era of imperialism (pre-1970 UNESCO Convention) as a wide range of opinions remains among museums.

Cultural nationalism

Cultural nationalism has links to retentionism,

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

, and particularism.

Following the

1970 UNESCO Convention and the

1995 UNIDROIT Convention, cultural nationalism has become more popular than its opposing internationalist theory.

Under the theory of cultural nationalism, nations seek to withhold cultural objects as their own heritage and actively seek the return of objects that are abroad (illegally or unethically).

Cultural nationalists suggest that keeping and returning objects to their country of origin tethers the object to its context and therefore overrides its economic value (abroad).

Both cultural nationalism and internationalism could be used to justify the retention of cultural property depending on the point of view. Nations of origin seek retention to protect the wider context of the object as well as the object itself, whereas nations who acquire cultural property seek its retention because they wish to preserve the object if there is a chance it will be lost if transported.

The repatriation debate often differs on case-by-case basis due to the specific nature of legal and historical issues surrounding each instance. Most of the arguments commonly used are discussed in the 2018

Report on the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage

''The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics'' (in French: ''Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle'') is a report written by Senegalese academic and ...

by

Felwine Sarr and

Bénédicte Savoy

Bénédicte Savoy (french: Bénédicte Savoy , born 22 May 1972 in Paris) is a French art historian, specialising in the critical enquiry of the provenance of works of art, including looted art and other forms of illegally acquired cultural obj ...

.

[Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: "Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle". Paris 2018; "The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics" (Download French original and English version, pdf, http://restitutionreport2018.com/)] They can be summarized as follows:

Arguments against repatriation

* Artifacts are a part of a

universal human history, and

encyclopedic

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

museums like the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

,

Musée du Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

and

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

cultivate the dissemination of knowledge, tolerance, and broad cultural understanding.

James Cuno

James "Jim" Bash Cuno (born April 6, 1951 in St. Louis) is an American art historian and curator. From 2011–22 Cuno served as President and Chief Executive Officer of the J. Paul Getty Trust.

Career

A native of St. Louis, Cuno received ...

suggests that repatriation claims are arguments against this encyclopedic promise.

* Artifacts were frequently excavated or uncovered by looters, who brought to light a piece of artwork that would otherwise never have been found; foreign-led excavation teams have uncovered items that contribute to cultural knowledge and understanding.

* Nationalist retentionist cultural property laws claiming ownership are founded on constructed boundaries of modern nations with weak connections to the culture, spirit, and ethnicity of the ancient peoples, who produced those works.

*Cultural identities are dynamic, inter-related and overlapping, so no modern nation-state can claim cultural property as their own without promoting a

sectarian view of culture.

* Having artwork disseminated around the world encourages international scholarly and professional exchange.

* Encyclopedic museums are located in cosmopolitan cities such as London, Paris, Berlin, Rome or New York, and if the artworks were to be moved, they would be seen by far fewer people. For instance, if the

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancien ...

were to be moved from The British Museum to The

Cairo Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or the Cairo Museum, in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an extensive collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities. It has 120,000 items, with a representative amount on display ...

, the number of people, who view it, would drop from about 5.5 million visitors to 2.5 million visitors a year.

Arguments for repatriation

* Encyclopedic museums such as the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

,

Musée du Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

and

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

were established as repositories for looted art during imperial and colonial rule, and thus are located in metropolitan cities out of view and reach of the cultures from which they were appropriated.

* Precedence of repatriated art has already been set in many cases, but the artworks that museums currently refuse to repatriate are often their most valuable and famous artworks.

* Foreign-led excavations have justified colonial rule and vice versa; in the pursuit of obtaining knowledge about the artifacts, there was a need to establish control over the artifacts and the countries, where they were located.

* The argument that art is a part of universal human history is a derivative of

colonial discourse that appropriated the art of other cultures into the Western historical narrative.

* The encyclopedic museums that house much of the world's artworks and artifacts are located in Western cities and privilege European scholars, professionals and people, while at the same time excluding people in the countries of origin.

* The argument that artwork will not be protected outside of the Western world is hypocritical, as much of the artwork transported out of colonized countries was crudely removed, often damaged and sometimes lost in transportation. The

Elgin marbles

The Elgin Marbles (), also known as the Parthenon Marbles ( el, Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, lit. "sculptures of the Parthenon"), are a collection of Classical Greece, Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of th ...

for example, were damaged during the cleaning and "preservation" process. As another example, the ''Napried'', one of the ships commissioned by

di Cesnola to transport approximately 35,000 pieces of antiquities that he had collected from

Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

, was lost at sea carrying about 5,000 pieces in its cargo.

* Art is best appreciated and understood in its original historical and cultural context.

Following the return of cultural property, the intangible meaning and aspects of that culture also return, this may promote the return of intangible traditions and educate future generations within indigenous communities.

* Art taken out of the country as a spoil of war, by looting, and as a deliberate act of colonialism, is unethical, even if this is not explicitly reflected in legislation. The possession of artwork taken under these conditions is a form of continued colonialism.

* The lack of existing legal recourse for claiming the return of illicitly appropriated cultural property is a result of colonization. Michael Dodson notes that colonization has taken "our distinct identities and cultures".

* Art is a symbol of cultural heritage and identity, and the unlawful appropriation of artworks is an affront to a nation's pride. Moira Simpson suggests that repatriation helps indigenous communities renew traditional practices that were previously lost, this is the best method of cultural preservation.

*Susan Douglas and Melanie Hayes note that national collections often have fixed practices, like collecting and owning cultural objects, which can be influenced by a colonial structure.

*Following the repatriation of cultural objects and ancestral remains, indigenous communities may begin to heal by connecting the past and the present.

The 'New Stream' theory (Indeterminacy)

Pauno Soirila argues that the majority of the repatriation debate is stuck in an "argumentative loop" with cultural nationalism and cultural internationalism on opposing sides, as evidenced by the unresolved case of the Parthenon marbles. Introducing external factors is the only way to break it.

Introducing claims centered around communities' human rights has led to increased indigenous defense and productive collaborations with museums and cultural institutions. While human rights factors alone cannot resolve the debate, it is a necessary step towards a sustainable cultural property policy.

International examples

Australia

Australian Aboriginal

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait I ...

cultural artefacts as well as people have been the objects of study in museums; many were taken in the decades either side of the turn of the 20th century. There has been greater success with returning human remains than cultural objects in recent years, as the question of repatriating objects is less straightforward than bringing home ancestors.

More than 100,000

Indigenous Australian

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

artefacts are held in over 220 institutions across the world, of which at least 32,000 are in British institutions, including the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and the

Victoria & Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

in

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

[

Australia has no laws directly governing repatriation, but there is a government programme relating to the return of Aboriginal remains and artefacts, the International Repatriation Program (IRP), administered by the Department of Communications and the Arts. This programme "supports the repatriation of ancestral remains and secret sacred objects to their communities of origin to help promote healing and reconciliation" and assists community representatives work towards repatriation of remains in various ways.]Gweagal

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the Dharawal people of Aboriginal Australians. Their descendants are traditional custodians of the southern geographic areas of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Country

The Gweagal lived on t ...

man Rodney Kelly and others have been working to achieve the repatriation of the Gweagal Shield and Spears from the British Museum and the , respectively. Jason Gibson, a museum anthropologist working in Central Australia, notes how there is a lack of Aboriginal authority surrounding collections and so protocols have instead been made by non-Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

professionals.

The matter of repatriation of cultural artefacts such as the Gweagal shield was raised in federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

on 9 December 2019, receiving cross-bench support. With the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook's landing looming in April 2020, two Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

MPs called on the government to “establish a process for the return of relevant cultural and historical artefacts to the original custodians and owners".

Returns

The Return of Cultural Heritage program run by the (AIATSIS) began in 2019, the year before the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

's first voyage to Australia. The program has worked towards the return of a number of the approximately 105,000 identified objects held by foreign institutions.[

In late October 2019 the first collection of many sacred artefacts held in US museums were returned by ]Illinois State Museum

The Illinois State Museum features the life, land, people and art of the State of Illinois. The headquarters museum is located on Spring and Edwards Streets, one block southwest of the Illinois State Capitol, in Springfield. There are three satell ...

.[ Forty-two Aranda (Arrernte) and ]Bardi Jawi

The Bardi people, also spelt Baada or Baardi and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people, living north of Broome and inhabiting parts of the Dampier Peninsula in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They are ethnically cl ...

objects removed from central Australia in 1920 were the first group. The next phase of the project would repatriate 40 culturally significant objects from the Manchester Museum

Manchester Museum is a museum displaying works of archaeology, anthropology and natural history and is owned by the University of Manchester, in England. Sited on Oxford Road ( A34) at the heart of the university's group of neo-Gothic buildings, ...

in the UK, which would be returned to the Aranda, Ganggalidda, Garawa, Nyamal and Yawuru

The Yawuru, also spelt Jawuru, are an Indigenous Australian people of the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Language

A Japanese linguist, Hosokawa Kōmei (細川弘明), compiled the first basic dictionary of the Yawuru language in 1988, a ...

peoples. AIATSIS project leader Christopher Simpson said they hoped that the project could evolve into an ongoing program for the Federal Government.Pilbara

The Pilbara () is a large, dry, thinly populated region in the north of Western Australia. It is known for its Aboriginal peoples; its ancient landscapes; the red earth; and its vast mineral deposits, in particular iron ore. It is also a g ...

region of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

.COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

, which was finally celebrated in May 2021. Another 17 items held at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection

The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia houses one of the finest Indigenous Australian art collections in the world, rivaling many of the collections held in Australia. It is the only museum outside Australia dedica ...

at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

also due to be returned to a number of Aboriginal nations.

Belgium

In Belgium, the Royal Museum of Central Africa (aka. Africa Museum) houses the largest collection of more than 180,000 cultural and natural history objects, mainly from the former Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, today's Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

(DRC). As part of its first major renovation in more than a 100 years, a new approach of “decolonization” towards the presentation of cultural heritage in the museum has been carried out. To this end, the public collections of the Africa Museum have been complemented by elements of contemporary life in the DRC. Also, Belgian sculptures showing Africans in a colonial context have been relegated to a special room on the history of the collections. The influence of the discussion in France has also led to announcements to change the relevant laws and to intensify cooperation with representatives of African countries.

Canada

The Haisla totem Pole

Totem poles ( hai, gyáaʼaang) are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually ...

of Kitimat, British Columbia

Kitimat is a district municipality in the North Coast region of British Columbia, Canada. It is a member municipality of the Regional District of Kitimat–Stikine regional government. The Kitimat Valley is part of the most populous urban distr ...

was originally prepared for chief G'psgoalux in 1872. This aboriginal artifact was donated to a Swedish museum in 1929. According to the donor, he had purchased the pole from the Haisla people

The Haisla (also known as Xa’islak’ala, X̄a’islakʼala, X̌àʼislakʼala, X̣aʼislak’ala, Xai:sla) are an amalgamation of two bands, the Kitamaat people of upper Douglas Channel and Devastation Channel and the Kitlope People of uppe ...

while he lived on the Canadian west coast and served as Swedish consul. After being approached by the Haisla people, the Swedish government decided in 1994 to return the pole, as the exact circumstances around the acquisition were unclear. The pole was returned to Kitimat in 2006 after a building had been constructed in order to preserve the pole.

During the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, the Glenbow museum received harsh criticism for their display “The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada's First People”. Initially, the criticism was due to the Olympic's association with Shell Oil who were exploring oil and gas in territories contested by Lubicon Cree

The Muskotew Sakahikan Enowuk or Lubicon Lake Nation ( cr, ᒪᐢᑯᑏᐤ ᓵᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ) is a Cree First Nation in northern Alberta, Canada. They are commonly referred to as the Lubicon Lake Nation, Lubicon Cree, or the Lubicon Lake C ...

. Later Mowhawk would sue the Glenbow museum for the repatriation of a False Face Mask

The False Face Society is a medicinal society in the Haudenosaunee, known especially for its wooden masks. Medicine societies are considered a vital part of the well-being of many Indigenous communities. The societies role within communities is to ...

they had displayed arguing that they considered it to be of religious ceremonial significance.

Turning the Page

' in 1992 that put forward a series of findings which would help improve Indigenous involvement in the museum process. Among these was a focus on creating a partnership between Indigenous people and the museum curators which involves allowing Indigenous people into the planning, research and implementation of collections. Museums were urged to also improve ongoing access to the collections and training for both curators and Indigenous people who want to be involved in the process. Finally, an emphasis was placed on repatriation claims of human remains, locally held objects (using practice customary to the Indigenous people in question) and foreign held objects.

In 1998, over 80 Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

ceremonial artifacts were repatriated to a cultural revitalization group by The University of Winnipeg. The controversy came as this group was not connected to the source community of the objects. Some of the objects were later returned but many are still missing.

Chile (Easter Island)

On Rapa Nui

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

, of the dozens of moai figures which have been removed from the landscape of Rapa Nui since the first one was removed in 1868 for installation in the British Museum, only one has been repatriated to date. This was a moai taken from the island in 1929 and repatriated in 2006.

China

China is still seeking the animal head statutes from the Old Summer Palace. 7 have been accounted for; 1 may have been sold at auction; 4 are still missing.

China is still seeking the animal head statutes from the Old Summer Palace. 7 have been accounted for; 1 may have been sold at auction; 4 are still missing.

Egypt

In July 2003, the Egyptians requested the return of the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancien ...

from the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

In 2019, Zahi Hawass

Zahi Abass Hawass ( ar, زاهي حواس; born May 28, 1947) is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, serving twice. He has also worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Wes ...

, an Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

archaeologist and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, relaunched the restitution

The law of restitution is the law of gains-based recovery, in which a court orders the defendant to ''give up'' their gains to the claimant. It should be contrasted with the law of compensation, the law of loss-based recovery, in which a court ...

campaign, asking the Berlin State Museums

The Berlin State Museums (german: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) are a group of institutions in Berlin, Germany, comprising seventeen museums in five clusters, several research institutes, libraries, and supporting facilities. They are overseen ...

, the British Museum and the Musée du Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

: “How can you refuse to lend to the new Grand Egyptian Museum

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM; ''al-Matḥaf al-Maṣriyy al-Kabīr''), also known as the Giza Museum, is an archaeological museum under construction in Giza, Egypt. It will house artifacts of ancient Egypt, including the complete Tutankhamun ...

when you have taken so many antiquities from Egypt?" All three museums refused his loan requests.bust of Nefertiti

The Nefertiti Bust is a painted stucco-coated limestone bust of Nefertiti, the Great Royal Wife of Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten. The work is believed to have been crafted in by Thutmose because it was found in his workshop in Amarna, Egypt. It ...

, and the Louvre Museum in Paris to return the Dendera Zodiac ceiling to Egypt.

Fiji

On 10 October 1874, Fiji's former king, Seru Epenisa Cakobau, gave his war club to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

when the Deed of Cession by which the sovereignty of Fiji passed to the British Crown was signed, and the war club was taken to Britain and kept at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. In October 1932, by a curious twist of fate, King Cakobau's war club was repatriated to Fiji, on behalf of the British king George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, for use as the ceremonial mace of the Legislative Council of Fiji.

Germany

Nefertiti Bust

The Nefertiti bust has become a cultural symbol of Berlin, where it is presented in the Neues Museum

The Neues Museum (English: ''New Museum'') is a listed building on the Museum Island in the historic centre of Berlin. Built from 1843 to 1855 by order of King Frederick William IV of Prussia in Neoclassical and Renaissance Revival styles, ...

, as well as of ancient Egypt. It has been the subject of intense arguments over Egyptian demands for its repatriation since the 1920s.