Aqil Agha on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aqil Agha al-Hasi ( ar, عقيل آغا الحاسي, given name also spelled ''Aqil'', ''Aqila'', ''Akil'' or ''Akili''; military title sometimes spelled ''Aga'') (died 1870) was the strongman of northern

Case Study 1: Akila Agha

. Throughout his rule, Aqil remained at least nominally in service to the Ottoman Empire, which paid him for protecting the roads of northern Palestine from Bedouin

p. 414

Aqil's Hawwara tribesmen in the

222

/ref> The Hawwara of the Galilee were actually from the Ainawiyeh tribe of the

35

Likewise,

347

Musa had two other sons, Ali and Salih.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, pp

222

223. Musa died in Gaza in 1830. Aqil's power base consisted of his tribesmen and alliances with other Bedouin tribes, who inhabited both sides of the

199

When the Ottomans regained control of Palestine in 1840–1841, Aqil returned to the

287

/ref> He recruited Egyptian irregulars from the Hanadi tribe and others who were left unemployed following the Egyptian withdrawal. Together with Aqil's Hawwara, they became a formidable local force. In 1843, Aqil became the chief of irregulars, known as ''

In 1848, Aqil assisted an expedition headed by

In 1848, Aqil assisted an expedition headed by

416

��418. Aqil and his Beni Sakhr allies quashed a party of Adwan Bedouin tribesmen when they attempted to rob Lynch's party. Lynch's record of Aqil's feat made him well known in Europe.

288

Among his assignments during the rebellion was the protection from Bedouin raiders of a supply route which the Ottomans used to send ammunition to their troops in Hauran. Aqil and his men accomplished the task successfully. Despite his successes during the Druze revolt, the authorities, with whom he always had a tense relationship, grew wary of his strength and subsequently arrested him in a nighttime raid. He was sent to

At the time of Aqil's escape, the Ottomans were engaged in the

At the time of Aqil's escape, the Ottomans were engaged in the

289

They were commanded by Shamdin's sons Muhammad Sa'id and Hasan Agha. Curious at this deployment, Aqil had requested an explanation from the ''kaimakam'' of Acre, but received no response. Thus Aqil concluded that the deployment was part of a conspiracy to upend his rule. In response, Aqil assembled his entire force of irregulars, amounting to some 300–400 men, and marched towards Shamdin's troops. Other Arab tribes volunteered their service, but Aqil declined their participation. On 30 March, the Kurdish irregulars confronted Aqil's irregulars and Bedouin allies at the

Aqil had been previously courted by European powers to secure protection for their Christian and Jewish protégés. During the

Aqil had been previously courted by European powers to secure protection for their Christian and Jewish protégés. During the

291

/ref> Bedouin raiding, now with the participation of the smaller tribes of the Galilee, resumed not long after Aqil's resignation and concerns by the local merchants and European consuls were voiced to Kapuli Pasha due to the incoming harvest season for cotton and grain from the Galilee and Hauran. Hasan Effendi sought to stem the tide of looting by attempting to play one Bedouin tribe off of the other. Kapuli Pasha was doubtful of this policy's effectiveness and strove to use military force instead. He personally led a contingent of troops in the Galilee and ensured a peaceful harvest through the end of 1863. However, Kapuli Pasha determined that he could not keep a large, permanent military contingent in the Galilee and decided to reinstate Aqil to his former position after lobbying from the British consul of Haifa. Kapuli Pasha's successor, Kurshid Pasha, resumed the anti-Bedouin operations in the Galilee in 1864 and sought to establish in the eastern Galilee four heavily armed forts as a bulwark against further raiding. Aqil entered into a conflict with the governor of

Aqil died in 1870, although his death was erroneously recorded by

Aqil died in 1870, although his death was erroneously recorded by

36

/ref> In the early 20th century, Rida Agha held the equivalent rank of a

3

/ref> When full Ottoman centralization in the Galilee was realized, local powers permanently lost their influence over the region's development. That power was instead passed on to wealthy businessmen from

p.79

ff)

p.414p.432

* * * * * * * * * * * * (pp.

120419420449

452498

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Aqil Agha 1870 deaths 19th-century Ottoman military personnel Arabs in Ottoman Palestine Ottoman rulers of Galilee People from Gaza City People from Nazareth People of the peasants' revolt in Palestine Prisoners and detainees of the Ottoman Empire Bedouin tribal chiefs

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

in the mid-19th century, during Ottoman rule. He was originally a commander of Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

irregular soldiers, known as the Hawwara tribe, in the service of the Ottoman governors of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

. His influence in the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

grew as he strengthened his alliances with the powerful Beni Sakhr

The Beni Sakhar confederacy is one of the largest and most influential tribal confederacies in Jordan. The Bani Sakher began migrating to Jordan as early as the 16th century and grew to become an influential tribe as by around the mid 18th century. ...

and Anizzah tribes of Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

, and recruited unemployed Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

irregulars from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

into his own band of irregulars, who thenceforth became known as the Hanadi tribe. He was known by his men and Western travelers to be courageous, cunning and charismatic, all qualities that contributed to his rise as the ''de facto'' ruler of the Galilee.Van Der Steen,Case Study 1: Akila Agha

. Throughout his rule, Aqil remained at least nominally in service to the Ottoman Empire, which paid him for protecting the roads of northern Palestine from Bedouin

raid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

s and for maintaining the security of this region. He also exacted his own tolls on the local population in return for ensuring their security. His friendly ties with the European governments were partially due to his protection of the local Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

ish communities in the Galilee, including his protection of Nazareth

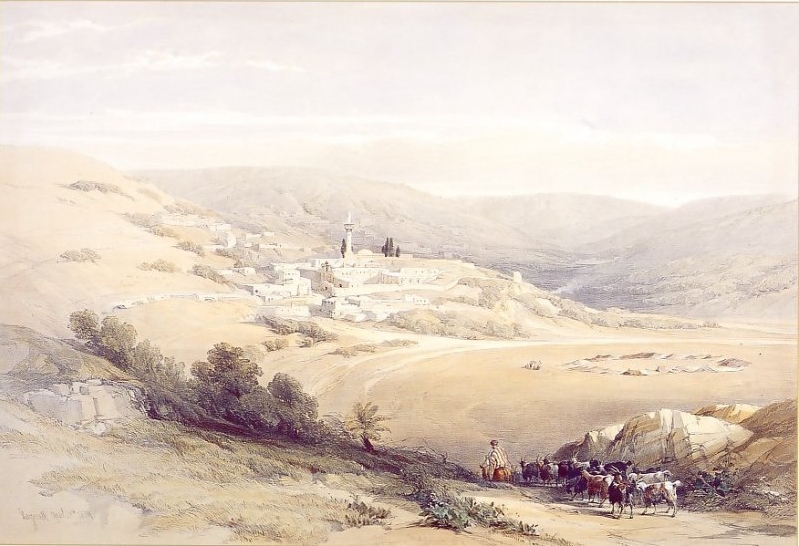

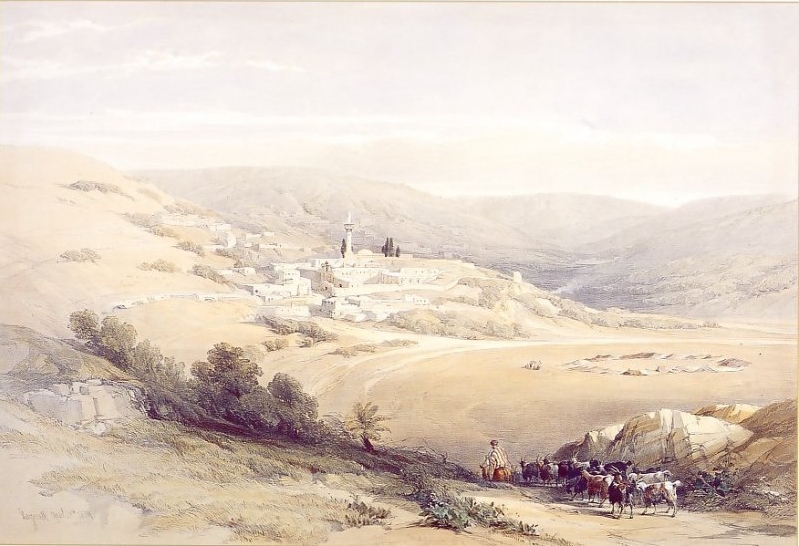

Nazareth ( ; ar, النَّاصِرَة, ''an-Nāṣira''; he, נָצְרַת, ''Nāṣəraṯ''; arc, ܢܨܪܬ, ''Naṣrath'') is the largest city in the Northern District of Israel. Nazareth is known as "the Arab capital of Israel". In ...

from the 1860 massacres that occurred in Ottoman Syria

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

. Aqil's relationship with the authorities was generally tense and he rebelled directly or indirectly against their local representatives. As a consequence of this frayed relationship, Aqil's employment would frequently be terminated when his activities or influence perturbed the authorities and then reinstated when his services were needed. By the time of his death, his influence had declined significantly. He was buried in his Galilee stronghold of I'billin

I'billin ( ar, إعبلين, he, אִעְבְּלִין) is a local council in the Northern District of Israel, near Shefa-'Amr. 'Ibillin was granted municipal status in 1960. The municipality's area is 18,000 dunams. In its population was ...

.

While Palestine had been under Ottoman rule from the early 16th century, direct imperial administrative rule was challenged by a series of local leaders who exhibited vast influence over local affairs between the 17th and 19th centuries. With the Empire embroiled in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, the power vacuum created in the area in the wake of Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Ottom ...

's rule in the Galilee (1730–1775), Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar

Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar ( ar, أحمد باشا الجزّار; ota, جزّار أحمد پاشا; ca. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of D ...

's rule (1776–1804), and Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

's rule (1831–1840), was filled by Aqil.Schölch, 1984, pp. 459–462. Aqil's demise represented the end of the last local obstacle to Ottoman centralization in Palestine.

Early life and family

Besides anecdotes provided in the writings of European consuls, most of the information on Aqil's life indirectly traces back to a history of the man written by Mikha'il Qa'war, aNazareth

Nazareth ( ; ar, النَّاصِرَة, ''an-Nāṣira''; he, נָצְרַת, ''Nāṣəraṯ''; arc, ܢܨܪܬ, ''Naṣrath'') is the largest city in the Northern District of Israel. Nazareth is known as "the Arab capital of Israel". In ...

clergyman. Aqil was born into a Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

family,Schölch, 1993, p. 199. known later as the Hanadi tribe. The actual Hanadi were an unrelated tribe that came to Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

during Egyptian rule in Palestine (1831–1840) and around 1840 joined Aqil's Hawwara tribesmen, who also had migrated from Egypt. The name "Hanadi" translates in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

as "Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

s" and the Hanadi irregulars were referred to as such by the inhabitants of Palestine because of their dark skin.Finn 1878p. 414

Aqil's Hawwara tribesmen in the

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

were not related to the well-known Hawwara

Hawwara (Berber: ''Ihuwwaren'', ), also spelled Huwwara, Howwara, Hewwara or Houara, is a large tribal confederation of Berbers and Arabized Berbers spread widely in the Maghreb, with descendants in Upper Egypt and Sudan. Hawwara are amongst the ...

tribe of Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient ...

, who were noted for their "bravery, horsemanship, and equipments" according to the Palestine Exploration Fund

The Palestine Exploration Fund is a British society based in London. It was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the study ...

.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, p.222

/ref> The Hawwara of the Galilee were actually from the Ainawiyeh tribe of the

Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, ...

ian desert region who had entered the service of Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar

Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar ( ar, أحمد باشا الجزّار; ota, جزّار أحمد پاشا; ca. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of D ...

while the latter was based in Egypt in the late 18th century. They came with al-Jazzar to northern Palestine when al-Jazzar became the powerful Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

-based Ottoman governor of Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

after the death of the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

strongman of the Galilee, Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Ottom ...

, in 1776. Al-Jazzar honored the Ainawiyeh tribesmen by giving them the name "Hawwara" to associate them with the famed Hawwara of Upper Egypt.

Aqil's father, Musa Agha al-Hasi, himself a commander of Hawwara irregulars in the service of Acre's Ottoman governors, had left Egypt for Gaza in 1814.Schölch, 1984, p. 462. He was not directly related to the Ainawiyeh or Hawwara tribes, but claimed descent from the Hawwara as a matter of convenience and prestige. Musa originally hailed from the al-Bara'asa tribe of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

(modern-day eastern Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

).Abujaber, 1989, p35

Likewise,

James Finn

James Finn (1806–1872) was a British Consul in Jerusalem, in the then Ottoman Empire (1846–1863). He arrived in 1845 with his wife Elizabeth Anne Finn. Finn was a devout Christian, who belonged to the London Society for Promoting Christia ...

, the British consul in Jerusalem (1846–1863), claims Aqil's family was of Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n or North African

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

origin. Musa Agha resided in the Galilee around 1820 and married a Turkmen woman. Aqil was born to the couple in the Nazareth area. According to historian Adel Manna, Aqil was born in Gaza.Mattar, 2005, p347

Musa had two other sons, Ali and Salih.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, pp

222

223. Musa died in Gaza in 1830. Aqil's power base consisted of his tribesmen and alliances with other Bedouin tribes, who inhabited both sides of the

Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. Aqil's brother, Salih Agha, held substantial influence in the Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

region. Mary Rogers, the sister of the English vice consul

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

, described in detail a banquet in Shefa-Amr

Shefa-Amr, also Shfar'am ( ar, شفاعمرو, Šafāʻamr, he, שְׁפַרְעָם, Šəfarʻam) is an Arab city in the Northern District of Israel. In it had a population of , with a Sunni Muslim majority and large Christian Arab and Druze m ...

and a gazelle hunt at the invitation of Salih Agha, while another traveler witnessed the lavish wedding between a son of Salih Agha and a daughter of Aqil Agha on "the plains of I'billin

I'billin ( ar, إعبلين, he, אִעְבְּלִין) is a local council in the Northern District of Israel, near Shefa-'Amr. 'Ibillin was granted municipal status in 1960. The municipality's area is 18,000 dunams. In its population was ...

", in circa 1857. Aqil married off another of his daughters to a Bedouin sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

(chieftain) in Gaza, paying the highest dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

registered at the time in Gaza: 11,000 piaster

The piastre or piaster () is any of a number of units of currency. The term originates from the Italian for "thin metal plate". The name was applied to Spanish and Hispanic American pieces of eight, or pesos, by Venetian traders in the Levant ...

s.Schölch, 1993, p. 206. The governor of Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

was reported to be a brother-in-law of Aqil.

Strongman of the Galilee

Consolidation of influence

Like his father before him, Aqil served various masters, among whom was Ibrahim Pasha, the son of Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Aqil defected from Ibrahim Pasha's army and joined local rebels in the 1834 peasants' revolt against Egyptian conscription and disarmament measures, leading his Hawwara irregulars in the Galilee. At some point during the revolt, Aqil helped save the mostlyDruze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

village of Isfiya

Isfiya ( ar, عسفيا, he, עִסְפִיָא), also known as Ussefiya or Usifiyeh, is a Druze-majority town and Local council (Israel), local council in northern Israel. Located on Mount Carmel, it is part of Haifa District. In its population ...

from being destroyed by Ibrahim Pasha's troops after its inhabitants paid Aqil for protection. As the revolt was suppressed, Aqil and his men left Palestine for Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

, where they sought the protection of that region's major Bedouin tribes. During his time in Transjordan he strengthened relations with these tribes.Manna, ed. Mattar, 2005, p199

When the Ottomans regained control of Palestine in 1840–1841, Aqil returned to the

Lower Galilee The Lower Galilee (; ar, الجليل الأسفل, translit=Al Jalil Al Asfal) is a region within the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. The Lower Galilee is bordered by the Jezreel Valley to the south; the Upper Galilee to t ...

and was commissioned as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of ten mounted irregulars.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, p287

/ref> He recruited Egyptian irregulars from the Hanadi tribe and others who were left unemployed following the Egyptian withdrawal. Together with Aqil's Hawwara, they became a formidable local force. In 1843, Aqil became the chief of irregulars, known as ''

bashi-bazouk

A bashi-bazouk ( ota, باشی بوزوق , , , roughly "leaderless" or "disorderly") was an irregular soldier of the Ottoman army, raised in times of war. The army chiefly recruited Albanians and Circassians as bashi-bazouks, but recruits ...

'', in northern Palestine,Schölch, 1984, p. 462. and his command was expanded to fifty horsemen. Aqil's irregulars became known in the area as the Hanadi, although the group's tribal composition was mixed.

Aqil angered the ''kaimakam

Kaymakam, also known by many other romanizations, was a title used by various officials of the Ottoman Empire, including acting grand viziers, governors of provincial sanjaks, and administrators of district kazas. The title has been retained a ...

'' (district governor) of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

, Muhammad Kubrisi, for his intervention in a dispute between two factions of the Catholic Church in Nazareth. One of the leaders of the Catholic factions, Sheikh Yusef Elias, had been dismissed by the church and subsequently entered Aqil's protection. He requested Aqil's intercession with Kubrisi, which was unsuccessful. When Sheikh Yusef decided to take matters into his own hands by raising a group of armed partisans in Nazareth, the church was compelled to restore his employment. Kubrisi believed Aqil had backed Sheikh Yusef's actions and accused Aqil of sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

. Kubrisi recalled Aqil and his Hawwara irregulars to Acre, verbally lambasted them and dismissed them all from service. Aqil was deeply insulted by Kubrisi's words and actions, and subsequently left for Transjordan where he sought the protection of the Beni Sakhr

The Beni Sakhar confederacy is one of the largest and most influential tribal confederacies in Jordan. The Bani Sakher began migrating to Jordan as early as the 16th century and grew to become an influential tribe as by around the mid 18th century. ...

tribe.

Aqil secured a durable alliance with the Beni Sakhr, consecrated through his marriage to a woman from the tribe. From Transjordan, he and his band of irregulars raided areas on both sides of the Jordan River until he was invited back to the Galilee by Acre's ''kaimakam'' in 1847. The latter had sought to neutralize Aqil and his allies' marauding activities, and thus pardoned Aqil. He was also given command of 75 ''bashi-bazouk'' in the Lower Galilee.Schölch, 1984, p. 463. Thereafter, he was commissioned with overseeing that region's security. In particular, the successive governors of Acre entrusted him with protecting the Galilee's trade routes and maintaining general security in the area, which he did successfully. With time, he became an unofficial '' mutasallim'' (tax collector) for much of northern Palestine, including the Jezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

, Safad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevat ...

, Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Fo ...

and Nazareth. The tax he collected was not on behalf of the authorities, but rather a tribute payment (''khuwwa'') to receive his protection. While this unofficial system proved successful in guaranteeing local security, later historians criticized it as akin to a protection racket

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

.

Encounter with William F. Lynch

In 1848, Aqil assisted an expedition headed by

In 1848, Aqil assisted an expedition headed by US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

captain William Francis Lynch

Captain William Francis Lynch (1 April 1801 – 17 October 1865) was a naval officer who served first in the United States Navy and later in the Confederate States Navy.

Personal life

William F. Lynch was born in Virginia. On 2 June 1828, on ...

to the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, and became known in the United States and Europe through the publication of Lynch's book that year. Vivid descriptions of Aqil by Lynch are quoted at length in the works of Finn. Lynch's first encounter with Aqil was in the ''divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

'' of Said Bey, the Ottoman ''kaimakam'' of Acre, and is recorded as follows:But what especially attracted my attention was a magnificent savage enveloped in a scarlet clothIn this meeting, Said Bey had attempted to dissuade Lynch of his plans to travel to the Dead Sea, with Aqil remarking that the Bedouin of the Ghor (Jordan Valley) would "eat them up". Lynch's reply was that "they would find us difficult of digestion," but he suggested that as Aqil seemed to hold influence with these tribes, he would be prepared to pay him to make the trip a more peaceable one. After the meeting ended, Lynch pursued Aqil to speak with him alone. He showed him his sword and revolver, which Aqil examined and declared to be the "Devil's invention". Lynch described the weaponry at the disposal of his men and asked Aqil if he thought it sufficient to make the journey to the Jordan, and Aqil replied that, "You will, if anyone can." Lynch later secured Aqil's accompaniment on the trip to the Dead Sea, through the intervention of an ex-pelisse A pelisse was originally a short fur-trimmed jacket which hussar light-cavalry soldiers from the 17th century onwards usually wore hanging loose over the left shoulder, ostensibly to prevent sword cuts. The name also came to refer to a fashionab ...richly embroidered with gold. He was the handsomest, and I soon thought also the most graceful being I had ever seen. His complexion was of a rich mellow indescribable olive tint, and his hair a glossy black; his teeth were regular and of the whitest ivory, and the glance of his eye was keen at times, but generally soft and lustrous. With the tarboosh upon his head which he seemed to wear uneasily, he reclined, rather than sat upon the opposite side of the divân, while his hand played in unconscious familiarity with thehilt The hilt (rarely called a haft or shaft) of a knife, dagger, sword, or bayonet is its handle, consisting of a guard, grip and pommel. The guard may contain a crossguard or quillons. A tassel or sword knot may be attached to the guard or pommel. ...of hisyataghan The yatagan, yataghan or ataghan (from Turkish ''yatağan''), also called varsak, is a type of Ottoman knife or short sabre used from the mid-16th to late 19th centuries. The yatagan was extensively used in Ottoman Turkey and in areas under imm .... He looked like one who would be 'Steel amid the din of arms, and wax when with the fair.'Finn 1878

p.415

Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, شريف مكة, Sharīf Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, شريف الحجاز, Sharīf al-Ḥijāz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

, describing the latter as "our counsellor, sagacious and prudent," and Aqil as, "the bold warrior and the admirable scout."Finn 1878, pp416

��418. Aqil and his Beni Sakhr allies quashed a party of Adwan Bedouin tribesmen when they attempted to rob Lynch's party. Lynch's record of Aqil's feat made him well known in Europe.

Hauran rebellion, imprisonment and escape

Aqil's irregulars attracted the membership of local individuals and small clans. Along with his alliance with the two powerful tribes of the region, the Beni Sakhr and the Anizzah, Aqil's autonomy in the Galilee was further strengthened, although he was nominally subordinate to the Ottoman authorities. He based himself in the Zaydani fortress ofI'billin

I'billin ( ar, إعبلين, he, אִעְבְּלִין) is a local council in the Northern District of Israel, near Shefa-'Amr. 'Ibillin was granted municipal status in 1960. The municipality's area is 18,000 dunams. In its population was ...

, a mixed Muslim-Christian village between Acre and Nazareth that was previously fortified by the family of Zahir al-Umar. By 1852, Aqil ceased residing in I'billin, preferring the traditional Bedouin lifestyle, dwelling in encampments and among his livestock. At this point, he ruled the area between Shefa-Amr to Beisan

Beit She'an ( he, בֵּית שְׁאָן '), also Beth-shean, formerly Beisan ( ar, بيسان ), is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is be ...

. He and his Hanadi tribesmen characteristically dressed in brown-striped robes.

In 1852, he was commissioned by the Ottoman authorities to prevent the spread of a Druze rebellion from Hauran

The Hauran ( ar, حَوْرَان, ''Ḥawrān''; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, eastwards by the al-Safa (Syria), al-Safa ...

to northern Palestine. He successfully satisfied this request, aided by his Bedouin allies.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, p288

Among his assignments during the rebellion was the protection from Bedouin raiders of a supply route which the Ottomans used to send ammunition to their troops in Hauran. Aqil and his men accomplished the task successfully. Despite his successes during the Druze revolt, the authorities, with whom he always had a tense relationship, grew wary of his strength and subsequently arrested him in a nighttime raid. He was sent to

Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

by sea and from there he was sent to serve a prison sentence at the Widin

Widin was the last attested Ostrogothic noble in Italy. After Teia's defeat at the hands of the Byzantine eunuch general Narses at the Battle of Mons Lactarius, south of present-day Naples, in October 552 or early 553, organized Ostrogothic resista ...

fortress on the Danube River

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. Aqil was apparently loaned some money from the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem

The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem ( la, Patriarchatus Latinus Hierosolymitanus) is the Latin Catholic ecclesiastical patriarchate in Jerusalem, officially seated in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It was originally established in 1099, wit ...

, who had accompanied him on the ship ride to Istanbul, and Aqil used those funds to purchase a fake passport. With the passport and a disguise, he and an Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

n inmate named Hasan Agha escaped Widin in 1854 and reached Salonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. From there, Aqil departed to Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and then Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

. Aqil resumed his Bedouin lifestyle of raiding and nomadic dwelling.

Reinstatement and Battle of Hattin

At the time of Aqil's escape, the Ottomans were engaged in the

At the time of Aqil's escape, the Ottomans were engaged in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, which left a domestic security void in its provinces due to the large number of provincial troops deployed to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. To restore security in the Galilee, Aqil was reassigned to his powerful post in the region in 1855. On his return to Palestine, Aqil's Hanadi tribesmen abandoned their conscription orders to serve with the Ottoman Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

in the Crimean War and instead returned to Aqil's service. Aqil was once again charged with protecting the routes of rural Palestine and occasionally Transjordan. He was once commissioned to collect taxes from Karak.

In Aqil's absence, a garrison of Kurdish irregulars based in Damascus had been left in charge of security in the Galilee. They were commanded by Shamdin Agha, but their employment was terminated by Aqil in 1855. Meanwhile, scores of Bedouin tribesmen from Faiyum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum ...

with kinship ties to Aqil's tribal irregulars had migrated to the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

as a result of their suppression by Sa'id Pasha

Mehmed Said Pasha ( ota, محمد سعيد پاشا ; 1838–1914), also known as Küçük Said Pasha ("Said Pasha the Younger") or Şapur Çelebi or in his youth as Mabeyn Başkatibi Said Bey, was an Ottoman monarchist, senator, statesman ...

of Egypt. Aqil welcomed their membership into his tribal band and their numbers subsequently swelled. He consecrated his relationship with the new arrivals by marrying a daughter of one of their ''sheikhs''. In May 1856, he defeated the Abd al-Hadi clan of Arraba Arraba ( ar, عرّابة) can refer to the following:

*Arraba, Israel

*Arraba, Jenin Other

*Arabah See also

*Araba (disambiguation) Araba may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

* the Ancient Arab Kingdom of Hatra, a Roman-Parthian buffer state ...

in a major clash that ended encroachments by the Abd al-Hadis on Aqil's territory.Schölch, 1984, p. 466.

In 1857, the Beirut-based governor of Sidon Eyalet

ota, ایالت صیدا

, common_name = Eyalet of Sidon

, subdivision = Eyalet

, nation = the Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 1660

, year_end = 1864

, date_start =

, date_end =

, eve ...

agreed to Shamdin's request to eliminate Aqil, who, to the consternation of the Ottoman authorities, was ruling the Galilee autonomously by that time. Shamdin, who sought vengeance against Aqil for terminating his service in the Galilee, had complained to the Sidon governor that Aqil was committing treachery by collaborating with the Bedouin tribes against Ottoman authority. The Ottomans, whose dependence on Aqil had decreased with the end of the Crimean War in 1856, found in Shamdin's request a convenient way to end Aqil's growing autonomy. When Aqil visited Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

to pay his respects to the governor of Sidon, he traveled with "the air of a sultan", according to the American missionary Henry H. Jessup, bringing with him a large and heavily armed Bedouin entourage.

Shamdin's forces, amounting to 600–700 Kurdish irregulars, massed in Tiberias.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, p289

They were commanded by Shamdin's sons Muhammad Sa'id and Hasan Agha. Curious at this deployment, Aqil had requested an explanation from the ''kaimakam'' of Acre, but received no response. Thus Aqil concluded that the deployment was part of a conspiracy to upend his rule. In response, Aqil assembled his entire force of irregulars, amounting to some 300–400 men, and marched towards Shamdin's troops. Other Arab tribes volunteered their service, but Aqil declined their participation. On 30 March, the Kurdish irregulars confronted Aqil's irregulars and Bedouin allies at the

Horns of Hattin

The Horns of Hattin ( he, קרני חיטין, Karnei Hittin ar, قرون حطين, Qurûn Hattîn) is an extinct volcano with twin peaks overlooking the plains of Hattin in the Lower Galilee, Israel.

Kurûn Hattîn is believed to be the site ...

, near the village of Hattin

Hittin ( ar, حطّين, transliteration, transliterated ''Ḥiṭṭīn'' ( ar, حِـطِّـيْـن) or ''Ḥaṭṭīn'' ( ar, حَـطِّـيْـن)) was a Palestinian people, Palestinian village located west of Tiberias before it was occ ...

. For the most part, both sides were armed with swords and spears and to a lesser extent, rifles, rather than the modern weaponry at the Ottoman military's disposal.Schölch, 1984, p. 470. Initially, the battle was going in Shamdin's favor and a portion of Aqil's troops began to flee. However, Salih Agha, Aqil's brother, led his group in a surprise attack against the Kurds. As a result, Shamdin's forces were dealt a decisive blow and commander Hasan Agha was among the 150 fatalities of that battle.

Aqil's victory entrenched his rule over the Galilee and afterward he established stronger relations with the Europeans. After Aqil's victory at Hattin, the Ottoman authorities distanced themselves from the incident in their correspondence with Aqil, but he accepted their explanations with a grain of salt

To take something with a "grain of salt" or "pinch of salt" is an English idiom that suggests to view something, specifically claims that may be misleading or unverified, with skepticism or to not interpret something literally.

In the old-fa ...

. In September 1858, Aqil was residing in Nazareth and decided not to intervene and put a stop to tribal clashes in the Jezreel Valley.

1860 events and protection of Christians

Aqil had been previously courted by European powers to secure protection for their Christian and Jewish protégés. During the

Aqil had been previously courted by European powers to secure protection for their Christian and Jewish protégés. During the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war

The 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus (also called the 1860 Syrian Civil War) was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon during Ottoman rule in 1860–1861 fought mainly between the local Druze and Christians. Following decisive Druze ...

, anti-Christian animosity spread to Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

where Christians were massacred by Druze and Muslim mobs. It appeared that the violence would spread to Acre as well, but Aqil issued direct orders to Acre's Muslim residents not to bring harm to the city's Christians, stating he would "chastise ... with his sword" anyone who violated the orders. Aqil also protected the Christian community of Nazareth from harm as their coreligionists elsewhere in Ottoman Syria faced massacres. Part of this protection included warnings to local Bedouin tribes to refrain from assaulting the town and warnings to its Christian and Muslim residents to prepare themselves militarily in case of attack. Aqil maintained a close friendship with Tannous Qawwar, a prominent Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

resident of the town.

In gratitude for protecting the Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

in Nazareth and Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

, Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

presented Aqil a gun and the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

medal in April 1861 aboard his French vessel docked at Haifa Bay

The Bay of Haifa or Haifa Bay ( he, מפרץ חיפה, ''Mifratz Heifa''), formerly Bay of Acre, is a bay along the Mediterranean coast of Northern Israel. Haifa Bay is Israel's only natural harbor on the Mediterranean.

''Haifa Bay'' also ref ...

.Schölch, 1984, p. 468. Edward, Prince of Wales (later King of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

) personally visited Aqil two years later to show his appreciation. Aqil offered Edward four Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse ( ar, الحصان العربي , DIN 31635, DMG ''ḥiṣān ʿarabī'') is a horse breed, breed of horse that originated on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is ...

s, but Edward politely declined. As a token of his appreciation, Edward gave Aqil a revolver.

His protection of the local Christians and his reputed Algerian origins drew comparisons with Abd al-Qader al-Jaza'iri, the exiled Algerian rebel who saved many Christians from harm during the 1860 riots in Damascus, and with whom Aqil developed ties.Schölch, 1984, p. 471. Aqil realized that European protection would strengthen his position towards the Ottoman rulers. After 1860, he courted the French, once sending a tiger as a present to "his Emperor" through the French consul in Beirut. According to Finn, Aqil was under special "French consideration".Schölch, 1993, p.201

Decline of influence

The Ottomanimperial government

The name imperial government (german: Reichsregiment) denotes two organs, created in 1500 and 1521, in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation to enable a unified political leadership, with input from the Princes. Both were composed of the em ...

adopted its Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. ...

modernization reforms in 1862 and originally entrusted Aqil with enforcing the new law of the land in northern Palestine. Part of these measures were stronger efforts to suppress the Bedouin tribes and decisively end their raiding activities. Aqil was given orders to prevent them from setting up camps in the cultivated lands of the Galilee and forbade the collection of ''khuwwa'' tolls from the local inhabitants. Aqil resigned from his post when he was informed that as part of his new assignment he and his men were required to don Ottoman uniforms. He objected to the requirement, insisting that as Bedouin, they were not accustomed to wearing uniforms. He was replaced by one of his Hawwara tribesmen, but Aqil compelled his successor to resign as well. Shortly after his resignation, the requirement of uniforms was canceled and Aqil resumed his assignment.

Aqil's closeness with the Europeans disturbed the Ottomans. His relations with the ''kaimakam'' of Acre, who in 1863 was Hasan Effendi, were also deteriorating. Since his return to Palestine in 1854, he avoided setting foot in the city, instead assigning a resident representative who engaged the ''kaimakam'' on his behalf. Hasan Effendi lodged complaints to the provincial governor in Beirut, Kapuli Pasha, about the misconduct of Aqil's men who extorted the local peasantry

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

. Indeed, Aqil's protection was generally limited to those who could pay for his services or otherwise benefit his interests, including merchants, travelers, monks, pilgrims, Christians and Jews.Schölch, 1984, p. 49.

The Tanzimat proved unpopular with large segments of the population and a Bedouin revolt broke out, with Transjordanian tribes launching raids against Tiberias and its countryside in the summer of 1863. Aqil was unable to stop the raids, and may have played a role in the revolt. In response, the Ottomans dispatched a 2,000-strong, artillery-backed force from Damascus and Acre to Tiberias. The presence of artillery caused the Transjordanian tribes to retreat. Aqil viewed this deployment as an attack on his jurisdiction and issued his resignation in protest, all the while hoping Kapuli Pasha would back down and reject his resignation. To that end, he had Jewish notables from Tiberias and the French consul of Beirut lobby on his behalf, but without success, as Kapuli Pasha, content to see the elimination of a local power such as Aqil, accepted his resignation.

After resigning, Aqil left the Galilee for Tell el-Hesi

Tell el-Hesi ( he, תל חסי), or Tell el-Hesy, is a 25-acre archaeological site in Israel. It was the first major site excavated in Palestine, first by Flinders Petrie in 1890 and later by Frederick Jones Bliss in 1891 and 1892, both sponsored ...

in the region of Gaza. Around this time, Aqil married off a daughter of his to the leading Bedouin ''sheikh'' of the area, Rabbah al-Wahaidi.Macalister and Masterman, 1906, p291

/ref> Bedouin raiding, now with the participation of the smaller tribes of the Galilee, resumed not long after Aqil's resignation and concerns by the local merchants and European consuls were voiced to Kapuli Pasha due to the incoming harvest season for cotton and grain from the Galilee and Hauran. Hasan Effendi sought to stem the tide of looting by attempting to play one Bedouin tribe off of the other. Kapuli Pasha was doubtful of this policy's effectiveness and strove to use military force instead. He personally led a contingent of troops in the Galilee and ensured a peaceful harvest through the end of 1863. However, Kapuli Pasha determined that he could not keep a large, permanent military contingent in the Galilee and decided to reinstate Aqil to his former position after lobbying from the British consul of Haifa. Kapuli Pasha's successor, Kurshid Pasha, resumed the anti-Bedouin operations in the Galilee in 1864 and sought to establish in the eastern Galilee four heavily armed forts as a bulwark against further raiding. Aqil entered into a conflict with the governor of

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and member of the Abd al-Hadi family, who tried to arrest Aqil. Kurshid Pasha dismissed Aqil by the end of the year. Fearing his arrest or death in light of the Ottomans' subsequent deployment of 200 Kurdish irregulars to Tiberias and the presence of military forces from Acre and Beirut in the western Galilee, Aqil fled to Salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

in the Balqa area of Transjordan.

Aqil later moved to Egypt. Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri and Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

lobbied the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

on Aqil's behalf and he was given permission to return to the Galilee in 1866. He subsequently inhabited the area of Mount Tabor

Mount Tabor ( he, הר תבור) (Har Tavor) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, west of the Sea of Galilee.

In the Hebrew Bible (Book of Joshua, Joshua, Book of Judges, Judges), Mount Tabor is the sit ...

. Despite his return and the reinstatement of a government salary, he was not able to restore his semi-autonomous authority in the region. In late 1869 he was awarded a medal of honor from the Habsburg dynasty

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

Death and legacy

Aqil died in 1870, although his death was erroneously recorded by

Aqil died in 1870, although his death was erroneously recorded by R. A. Stewart Macalister

Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister (8 July 1870 – 26 April 1950) was an Irish archaeologist.

Biography

Macalister was born in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Alexander Macalister, then Professor of Zoology, University of Dublin. His father wa ...

to have occurred in 1867. According to Macalister, Aqil died in the vicinity of Shefa-Amr. He was buried in I'billin, his previous Galilee headquarters. As of the early 1980s, descendants of Aqil still inhabited I'billin.Schölch, 1984, p. 464.

Aqil's son Quwaytin succeeded him as the chief of the Hanadi tribesmen who continued to inhabit the Galilee and its vicinity. In the late 19th century, Quwaytin's tribe had some 900 members and was based in the northern Jordan Valley. Quwaytin donned the honor cross medallions given to his father by various European governments. However, Hanadi influence and strength in the region diminished under Quwaytin and was gradually suppressed by various Ottoman actors, eventually reducing the Hanadi to an ineffectual tribe. Quwaytin's son and successor Rida also entered into Ottoman service and held the title of '' agha'' like Aqil.Abujaber, 1989, p36

/ref> In the early 20th century, Rida Agha held the equivalent rank of a

lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

and served as commander of police in the Balqa Sanjak in Transjordan.

For nearly two decades Aqil had been a major local power in northern Palestine.Schölch, 1993, pp. 207–208 He asserted to other tribal ''sheikhs'' that the land they roamed in belonged to the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

s and that one day they would take it back from the Turkish Ottoman "conquerors".Schölch, 1984, p. 465. According to Finn, Aqil may have ultimately envisioned forming an Arab confederation in the southern Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

independent of the Ottomans and backed by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. However, despite these perceived intentions, Aqil ruled under the auspices of the Ottoman authorities, was paid by them, and was at least partially dependent upon their support. His ties with France and Europe contributed to his power, but he lacked the necessary support from these countries to pursue any desire of independence that he had. Aqil's death marked the removal of "the last obstacle to the implementation of full centralized Ottoman rule" in northern Palestine, according to historian Mahmoud Yazbak.Yazbak, 1998, p3

/ref> When full Ottoman centralization in the Galilee was realized, local powers permanently lost their influence over the region's development. That power was instead passed on to wealthy businessmen from

Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, ultimately leaving the Sursock family

The Sursock family (also spelled Sursuq) is a Greek Orthodox Christian family from Lebanon, and used to be one of the most important families of Beirut. Having originated in Constantinople during the Byzantine Empire, the family has lived in Beir ...

of Beirut as the new "masters" of the Galilee, according to anthropologist Alexander Schölch; within another half a century, the area was sold to Zionist colonists in the Sursock Purchase

The Sursock Purchase of the Jezreel Valley and Haifa Bay, as well as other parts of Mandatory Palestine, was the largest Jewish land purchase in Palestine during the period of early Jewish immigration.

The Jezreel Valley was considered the most f ...

.

One of the factors Schölch attributes to Aqil's failure to secure an autonomous rule similar to that of the Arab ''sheikh'' Zahir al-Umar was Aqil's refusal to accept a sedentary life.Schölch, 1984, p. 472. While I'billin frequently functioned as a headquarters of sorts for Aqil, he did not take up permanent residence there, or anywhere. Instead it served as a symbol of his authority in the Galilee. Aqil was adamantly a Bedouin and once remarked to William Lynch that it would be a "disgrace" to "till the ground like a ''fellah

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

''". The nomadic, marauding lifestyle of Aqil ran counter to the modernization efforts of the Ottomans, which strongly encouraged settlement of the land and centralization

Centralisation or centralization (see spelling differences) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, framing strategy and policies become concentrated within a particu ...

. These processes were eventually embraced by the peasantry and the urban notables, but resisted by the Bedouin tribes whose traditional livelihoods were at risk.

Schölch asserts that Aqil contributed little to the socio-economic development of Palestine, and was not a "benefactor of the peasants".Schölch, 1984, p. 473. However, Aqil is described in a mostly positive light by modern-day sources and in local tradition. In the Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

political atmosphere that followed the Ottoman Empire's fall in 1917, Aqil's Arab identity and his struggles against the Ottomans contributed to the prevailing positive commemoration of his life. Palestinian Christians in particular remember him fondly for protecting Christians during his rule.

References

Bibliography

* * *p.79

ff)

p.414

* * * * * * * * * * * * (pp.

120

452

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Aqil Agha 1870 deaths 19th-century Ottoman military personnel Arabs in Ottoman Palestine Ottoman rulers of Galilee People from Gaza City People from Nazareth People of the peasants' revolt in Palestine Prisoners and detainees of the Ottoman Empire Bedouin tribal chiefs