Apollo 16 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by

The insignia of Apollo 16 is dominated by a rendering of an

The insignia of Apollo 16 is dominated by a rendering of an

The Ad Hoc Apollo Site Evaluation Committee met in April and May 1971 to decide the Apollo 16 and 17 landing sites; it was chaired by

The Ad Hoc Apollo Site Evaluation Committee met in April and May 1971 to decide the Apollo 16 and 17 landing sites; it was chaired by

In addition to the usual Apollo spacecraft training, Young and Duke, along with backup commander Fred Haise, underwent an extensive

In addition to the usual Apollo spacecraft training, Young and Duke, along with backup commander Fred Haise, underwent an extensive  In addition to the field geology training, Young and Duke also trained to use their EVA space suits, adapt to the reduced lunar gravity, collect samples, and drive the Lunar Roving Vehicle. The fact that they had been backups for Apollo 13, planned to be a landing mission, meant that they could spend about 40 percent of their time training for their surface operations. They also received survival training and prepared for technical aspects of the mission. The astronauts spent much time studying the lunar samples brought back by earlier missions, learning about the instruments to be carried on the mission, and hearing what the principal investigators in charge of those instruments expected to learn from Apollo 16. This training helped Young and Duke, while on the Moon, quickly realize that the expected volcanic rocks were not there, even though the geologists in Mission Control initially did not believe them. Much of the training—according to Young, 350 hours—was conducted with the crew wearing space suits, something that Young deemed vital, allowing the astronauts to know the limitations of the equipment in doing their assigned tasks. Mattingly also received training in recognizing geological features from orbit by flying over the field areas in an airplane, and trained to operate the Scientific Instrument Module from lunar orbit.

In addition to the field geology training, Young and Duke also trained to use their EVA space suits, adapt to the reduced lunar gravity, collect samples, and drive the Lunar Roving Vehicle. The fact that they had been backups for Apollo 13, planned to be a landing mission, meant that they could spend about 40 percent of their time training for their surface operations. They also received survival training and prepared for technical aspects of the mission. The astronauts spent much time studying the lunar samples brought back by earlier missions, learning about the instruments to be carried on the mission, and hearing what the principal investigators in charge of those instruments expected to learn from Apollo 16. This training helped Young and Duke, while on the Moon, quickly realize that the expected volcanic rocks were not there, even though the geologists in Mission Control initially did not believe them. Much of the training—according to Young, 350 hours—was conducted with the crew wearing space suits, something that Young deemed vital, allowing the astronauts to know the limitations of the equipment in doing their assigned tasks. Mattingly also received training in recognizing geological features from orbit by flying over the field areas in an airplane, and trained to operate the Scientific Instrument Module from lunar orbit.

The PSE added to the network of seismometers left by Apollo 12, 14 and 15. NASA intended to calibrate the Apollo 16 PSE by crashing the LM's ascent stage near it after the astronauts were done with it, an object of known mass and velocity impacting at a known location. However, NASA lost control of the ascent stage after jettison, and this did not occur. The ASE, designed to return data about the Moon's geologic structure, consisted of two groups of explosives: one, a line of "thumpers" were to be deployed attached to three

The PSE added to the network of seismometers left by Apollo 12, 14 and 15. NASA intended to calibrate the Apollo 16 PSE by crashing the LM's ascent stage near it after the astronauts were done with it, an object of known mass and velocity impacting at a known location. However, NASA lost control of the ascent stage after jettison, and this did not occur. The ASE, designed to return data about the Moon's geologic structure, consisted of two groups of explosives: one, a line of "thumpers" were to be deployed attached to three  The LSM was designed to measure the strength of the Moon's

The LSM was designed to measure the strength of the Moon's

The Apollo 16 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 pm EST on April 16, 1972. The launch was nominal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that on previous missions. The first and second stages of the SaturnV (the S-IC and

The Apollo 16 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 pm EST on April 16, 1972. The launch was nominal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that on previous missions. The first and second stages of the SaturnV (the S-IC and  By the time Mission Control issued the wake-up call to the crew for flight day two, the spacecraft was about away from the Earth, traveling at about . As it was not due to arrive in lunar orbit until flight day four, flight days two and three were largely preparatory, consisting of spacecraft maintenance and scientific research. On day two, the crew performed an

By the time Mission Control issued the wake-up call to the crew for flight day two, the spacecraft was about away from the Earth, traveling at about . As it was not due to arrive in lunar orbit until flight day four, flight days two and three were largely preparatory, consisting of spacecraft maintenance and scientific research. On day two, the crew performed an

The crew continued preparing for lunar module activation and undocking shortly after waking up to begin flight day five. The boom that extended the

The crew continued preparing for lunar module activation and undocking shortly after waking up to begin flight day five. The boom that extended the

Waking up three and a half minutes earlier than planned, they discussed the day's timeline of events with Houston. The second lunar excursion's primary objective was to visit Stone Mountain to climb up the slope of about 20 degrees to reach a cluster of five craters known as " Cinco craters". They drove there in the LRV, traveling from the LM. At above the valley floor, the pair were at the highest elevation above the LM of any Apollo mission. They marveled at the view (including South Ray) from the side of Stone Mountain, which Duke described as "spectacular", then gathered samples in the vicinity. After spending 54 minutes on the slope, they climbed aboard the lunar rover en route to the day's second stop, dubbed Station 5, a crater across. There, they hoped to find Descartes material that had not been contaminated by ejecta from South Ray Crater, a large crater south of the landing site. The samples they collected there, although their origin is still not certain, are, according to geologist Wilhelms, "a reasonable bet to be Descartes".

The next stop, Station 6, was a blocky crater, where the astronauts believed they could sample the Cayley Formation as evidenced by the firmer soil found there. Bypassing station seven to save time, they arrived at Station 8 on the lower flank of Stone Mountain, where they sampled material on a ray from South Ray crater for about an hour. There, they collected black and white breccias and smaller,

Waking up three and a half minutes earlier than planned, they discussed the day's timeline of events with Houston. The second lunar excursion's primary objective was to visit Stone Mountain to climb up the slope of about 20 degrees to reach a cluster of five craters known as " Cinco craters". They drove there in the LRV, traveling from the LM. At above the valley floor, the pair were at the highest elevation above the LM of any Apollo mission. They marveled at the view (including South Ray) from the side of Stone Mountain, which Duke described as "spectacular", then gathered samples in the vicinity. After spending 54 minutes on the slope, they climbed aboard the lunar rover en route to the day's second stop, dubbed Station 5, a crater across. There, they hoped to find Descartes material that had not been contaminated by ejecta from South Ray Crater, a large crater south of the landing site. The samples they collected there, although their origin is still not certain, are, according to geologist Wilhelms, "a reasonable bet to be Descartes".

The next stop, Station 6, was a blocky crater, where the astronauts believed they could sample the Cayley Formation as evidenced by the firmer soil found there. Bypassing station seven to save time, they arrived at Station 8 on the lower flank of Stone Mountain, where they sampled material on a ray from South Ray crater for about an hour. There, they collected black and white breccias and smaller,

Flight day seven was their third and final day on the lunar surface, returning to orbit to rejoin Mattingly in the CSM following the day's moonwalk. During the third and final lunar excursion, they were to explore North Ray crater, the largest of any of the craters any Apollo expedition had visited. After exiting ''Orion'', the pair drove to North Ray crater. The drive was smoother than that of the previous day, as the craters were shallower and boulders were less abundant north of the immediate landing site. After passing Palmetto crater, boulders gradually became larger and more abundant as they approached North Ray in the lunar rover. Upon arriving at the rim of North Ray crater, they were away from the LM. After their arrival, the duo took photographs of the wide and deep crater. They visited a large boulder, taller than a four-story building, which became known as 'House Rock'. Samples obtained from this boulder delivered the final blow to the pre-mission volcanic hypothesis, proving it incorrect. House Rock had numerous bullet hole-like marks where

Flight day seven was their third and final day on the lunar surface, returning to orbit to rejoin Mattingly in the CSM following the day's moonwalk. During the third and final lunar excursion, they were to explore North Ray crater, the largest of any of the craters any Apollo expedition had visited. After exiting ''Orion'', the pair drove to North Ray crater. The drive was smoother than that of the previous day, as the craters were shallower and boulders were less abundant north of the immediate landing site. After passing Palmetto crater, boulders gradually became larger and more abundant as they approached North Ray in the lunar rover. Upon arriving at the rim of North Ray crater, they were away from the LM. After their arrival, the duo took photographs of the wide and deep crater. They visited a large boulder, taller than a four-story building, which became known as 'House Rock'. Samples obtained from this boulder delivered the final blow to the pre-mission volcanic hypothesis, proving it incorrect. House Rock had numerous bullet hole-like marks where

Eight minutes before the planned departure from the lunar surface, CAPCOM

Eight minutes before the planned departure from the lunar surface, CAPCOM

The ''Ticonderoga'' delivered the Apollo 16 command module to the North Island Naval Air Station, near San Diego, California, on Friday, May 5, 1972. On Monday, May 8, ground service equipment being used to empty the residual toxic reaction control system fuel in the command module tanks exploded in a Naval Air Station hangar. Forty-six people were sent to the hospital for 24 to 48 hours' observation, most suffering from inhalation of toxic fumes. Most seriously injured was a technician who suffered a fractured kneecap when a cart overturned on him. A hole was blown in the hangar roof 250 feet above; about 40 windows in the hangar were shattered. The command module suffered a three-inch gash in one panel.

The Apollo 16 command module ''Casper'' is on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in

The ''Ticonderoga'' delivered the Apollo 16 command module to the North Island Naval Air Station, near San Diego, California, on Friday, May 5, 1972. On Monday, May 8, ground service equipment being used to empty the residual toxic reaction control system fuel in the command module tanks exploded in a Naval Air Station hangar. Forty-six people were sent to the hospital for 24 to 48 hours' observation, most suffering from inhalation of toxic fumes. Most seriously injured was a technician who suffered a fractured kneecap when a cart overturned on him. A hole was blown in the hangar roof 250 feet above; about 40 windows in the hangar were shattered. The command module suffered a three-inch gash in one panel.

The Apollo 16 command module ''Casper'' is on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in  Duke left two items on the Moon, both of which he photographed while there. One is a plastic-encased photo portrait of his family. The reverse of the photo is signed by Duke's family and bears this message: "This is the family of Astronaut Duke from Planet Earth. Landed on the Moon, April 1972." The other item was a commemorative medal issued by the United States Air Force, which was celebrating its 25th anniversary in 1972. He took two medals, leaving one on the Moon and donating the other to the

Duke left two items on the Moon, both of which he photographed while there. One is a plastic-encased photo portrait of his family. The reverse of the photo is signed by Duke's family and bears this message: "This is the family of Astronaut Duke from Planet Earth. Landed on the Moon, April 1972." The other item was a commemorative medal issued by the United States Air Force, which was celebrating its 25th anniversary in 1972. He took two medals, leaving one on the Moon and donating the other to the

Apollo 16 Traverses

Lunar Photomap 78D2S2(25)

by Gene Simmons, NASA, EP-95, 1972

''Apollo 16: "Nothing so hidden..."'' (Part 1)

– NASA film on the Apollo 16 mission at the

''Apollo 16: "Nothing so hidden..."'' (Part 2)

– NASA film on the Apollo 16 mission at the Internet Archive

Apollo Lunar Surface VR Panoramas

– QTVR panoramas at moonpans.com

Apollo 16 Science Experiments

at the

Audio recording of Apollo 16 landing

as recorded at the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station

Interview with the Apollo 16 Astronauts (28 June 1972)

from th

Commonwealth Club of California Records

at th

Hoover Institution Archives

– Apollo 16 film footage of lunar rover at the

Astronaut's Eye View of Apollo 16 Site

from

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended stay on the lunar surface

The geology of the Moon (sometimes called selenology, although the latter term can refer more generally to " lunar science") is quite different from that of Earth. The Moon lacks a true atmosphere, which eliminates erosion due to weather. It does ...

, a focus on science, and the use of the Lunar Roving Vehicle

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) is a battery-powered four-wheeled rover used on the Moon in the last three missions of the American Apollo program ( 15, 16, and 17) during 1971 and 1972. It is popularly called the Moon buggy, a play on the ...

(LRV). The landing and exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

were in the Descartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after ...

, a site chosen because some scientists expected it to be an area formed by volcanic action, though this proved to not be the case.

The mission was crewed by Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

John Young John Young may refer to:

Academics

* John Young (professor of Greek) (died 1820), Scottish professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow

* John C. Young (college president) (1803–1857), American educator, pastor, and president of Centre Coll ...

, Lunar Module Pilot

Lunar most commonly means "of or relating to the Moon".

Lunar may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lunar'' (series), a series of video games

* "Lunar" (song), by David Guetta

* "Lunar", a song by Priestess from the 2009 album ''Prior t ...

Charles Duke

Charles Moss Duke Jr. (born October 3, 1935) is an American former astronaut, United States Air Force (USAF) officer and test pilot. As Lunar Module pilot of Apollo 16 in 1972, he became the tenth and youngest person to walk on the Moon, at ...

and Command Module Pilot

Command may refer to:

Computing

* Command (computing), a statement in a computer language

* COMMAND.COM, the default operating system shell and command-line interpreter for DOS

* Command key, a modifier key on Apple Macintosh computer keyboards

* ...

Ken Mattingly

Thomas Kenneth Mattingly II (born March 17, 1936) is an American former aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, rear admiral in the United States Navy and astronaut who flew on the Apollo 16, STS-4 and STS-51-C missions.

Mattingly had b ...

. Launched from the Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten field centers. Since December 196 ...

in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

on April 16, 1972, Apollo 16 experienced a number of minor glitches en route to the Moon. These culminated with a problem with the spaceship's main engine that resulted in a six-hour delay in the Moon landing as NASA managers contemplated having the astronauts abort the mission and return to Earth, before deciding the problem could be overcome. Although they permitted the lunar landing, NASA had the astronauts return from the mission one day earlier than planned.

After flying the lunar module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

to the Moon's surface on April 21, Young and Duke spent 71 hours—just under three days—on the lunar surface, during which they conducted three extravehicular activities

Extravehicular activity (EVA) is any activity done by an astronaut in outer space outside a spacecraft. In the absence of a breathable Earthlike atmosphere, the astronaut is completely reliant on a space suit for environmental support. EVA inc ...

or moonwalks, totaling 20 hours and 14 minutes. The pair drove the lunar rover, the second used on the Moon, for . On the surface, Young and Duke collected of lunar samples for return to Earth, including Big Muley

Lunar Sample 61016, better known as "Big Muley", is a lunar sample discovered and collected on the Apollo 16 mission in 1972 in the Descartes Highlands, on the rim of Plum crater, near Flag crater (Station 1). It is the largest sample returned fr ...

, the largest Moon rock

Moon rock or lunar rock is rock originating from Earth's Moon. This includes lunar material collected during the course of human exploration of the Moon, and rock that has been ejected naturally from the Moon's surface and landed on Earth a ...

collected during the Apollo missions. During this time Mattingly orbited the Moon in the command and service module

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother sh ...

(CSM), taking photos and operating scientific instruments. Mattingly, in the command module, spent 126 hours and 64 revolutions in lunar orbit

In astronomy, lunar orbit (also known as a selenocentric orbit) is the orbit of an object around the Moon.

As used in the space program, this refers not to the orbit of the Moon about the Earth, but to orbits by spacecraft around the Moon. Th ...

. After Young and Duke rejoined Mattingly in lunar orbit, the crew released a subsatellite from the service module

A service module (also known as an equipment module or instrument compartment) is a component of a crewed space capsule containing a variety of support systems used for spacecraft operations. Usually located in the uninhabited area of the spacec ...

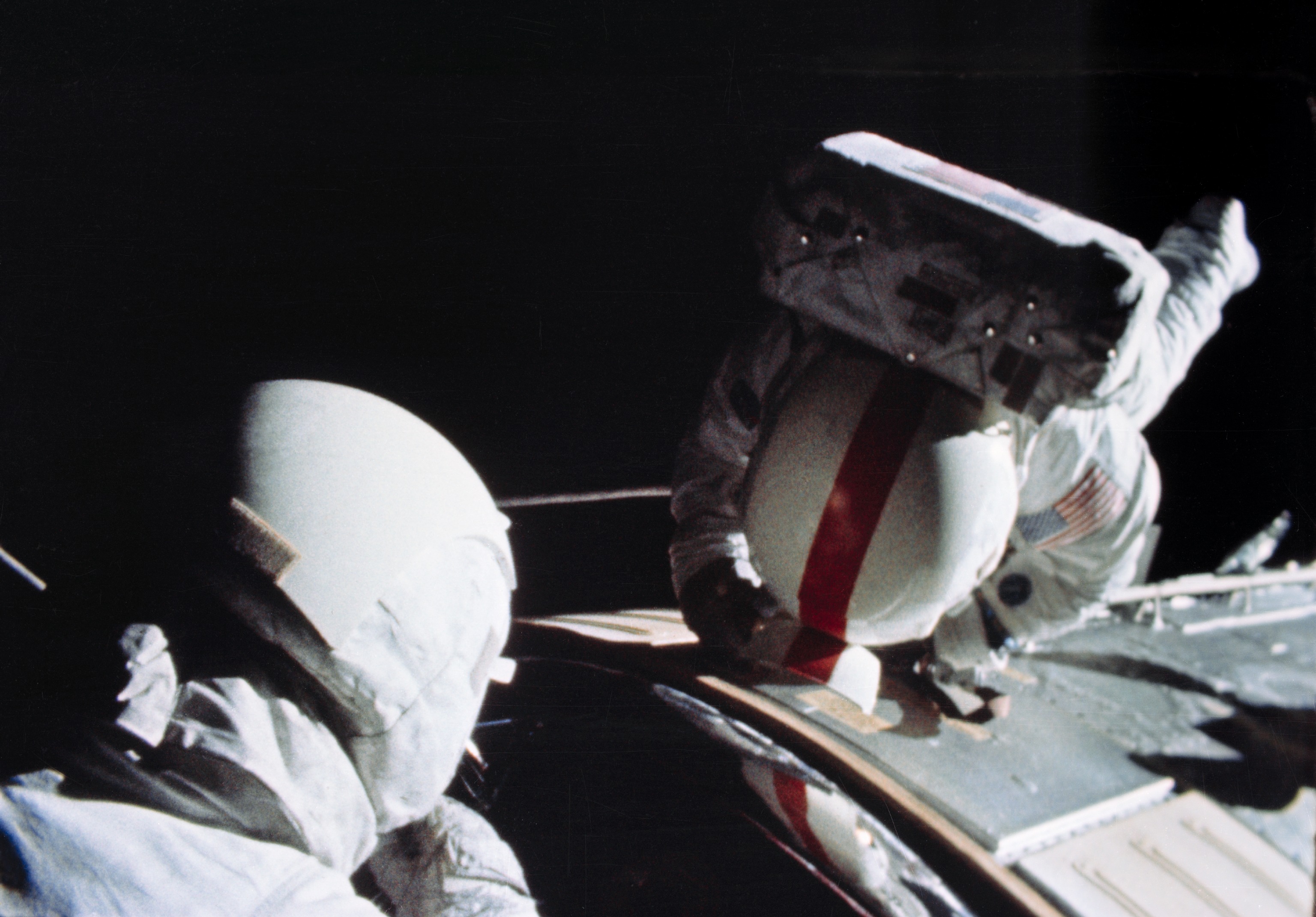

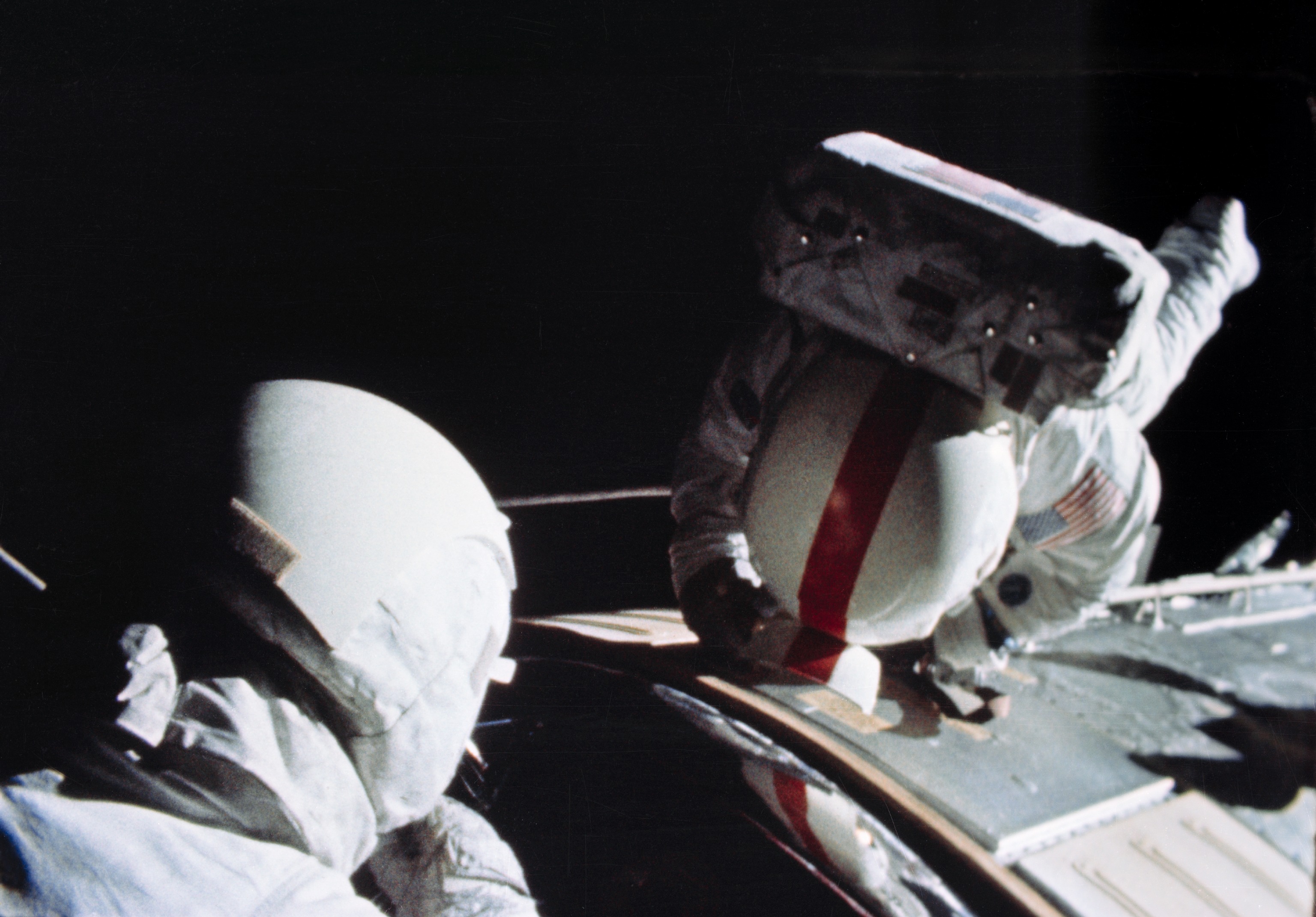

(SM). During the return trip to Earth, Mattingly performed a one-hour spacewalk to retrieve several film cassettes from the exterior of the service module. Apollo 16 returned safely to Earth on April 27, 1972.

Crew and key Mission Control personnel

John Young, the mission commander, was 41 years old and acaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

at the time of Apollo 16. Becoming an astronaut in 1962 as part of the second group to be selected by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

, he flew in Gemini 3

Gemini 3 was the first crewed mission in NASA's Project Gemini and was the first time two American astronauts flew together into space. On March 23, 1965, astronauts Gus Grissom and John Young flew three low Earth orbits in their spacecraft, ...

with Gus Grissom

Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom (April 3, 1926 – January 27, 1967) was an American engineer, pilot in the United States Air Force, and member of the Mercury Seven selected by National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) as Project Mercur ...

in 1965, becoming the first American not of the Mercury Seven

The Mercury Seven were the group of seven astronauts selected to fly spacecraft for Project Mercury. They are also referred to as the Original Seven and Astronaut Group 1. Their names were publicly announced by NASA on April 9, 1959; these sev ...

to fly in space. He thereafter flew in Gemini 10 (1966) with Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and ...

and as command module pilot of Apollo 10

Apollo 10 (May 18–26, 1969) was a human spaceflight, the fourth crewed mission in the United States Apollo program, and the second (after Apollo8) to orbit the Moon. NASA described it as a "dress rehearsal" for the first Moon landing, and ...

(1969). With Apollo 16, he became the second American, after Jim Lovell

James Arthur Lovell Jr. (; born March 25, 1928) is an American retired astronaut, naval aviator, test pilot and mechanical engineer. In 1968, as command module pilot of Apollo 8, he became, with Frank Borman and William Anders, one of th ...

, to fly in space four times.

Thomas Kenneth "Ken" Mattingly, the command module pilot, was 36 years old and a lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

in the Navy at the time of Apollo 16. Mattingly had been selected in NASA's fifth group of astronauts in 1966. He was a member of the support crew for Apollo 8

Apollo 8 (December 21–27, 1968) was the first crewed spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and the first human spaceflight to reach the Moon. The crew orbited the Moon ten times without landing, and then departed safely back to Earth. The ...

and Apollo 9

Apollo 9 (March 313, 1969) was the third human spaceflight in NASA's Apollo program. Flown in low Earth orbit, it was the second crewed Apollo mission that the United States launched via a Saturn V rocket, and was the first flight of the ful ...

. Mattingly then undertook parallel training with Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

's backup CMP, William Anders

William Alison Anders (born 17 October 1933) is a retired United States Air Force (USAF) major general, former electrical engineer, nuclear engineer, NASA astronaut, and businessman. In December 1968, he was a member of the crew of Apollo 8, t ...

, who had announced his resignation from NASA effective at the end of July 1969 and would thus be unavailable if the first lunar landing mission was postponed. Had Anders left NASA before Apollo 11 flew, Mattingly would have taken his place on the backup crew.

Mattingly had originally been assigned to the prime crew of Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

, but was exposed to rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and ...

through Charles Duke, at that time with Young on Apollo 13's backup crew; Duke had caught it from one of his children. Mattingly never contracted the illness, but three days before launch was removed from the crew and replaced by his backup, Jack Swigert

John Leonard Swigert Jr. (August 30, 1931 – December 27, 1982) was an American NASA astronaut, test pilot, mechanical engineer, aerospace engineer, United States Air Force pilot, and politician. In April 1970, as command module pilot of Ap ...

. Duke, also a Group 5 astronaut and a space rookie, had served on the support crew of Apollo 10 and was a capsule communicator

Flight controllers are personnel who aid space flight by working in such Mission Control Centers as NASA's Mission Control Center or ESA's European Space Operations Centre. Flight controllers work at computer consoles and use telemetry to ...

(CAPCOM) for Apollo 11. A lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

in the Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

, Duke was 36 years old at the time of Apollo 16, which made him the youngest of the twelve astronauts who walked on the Moon during Apollo as of the time of the mission. All three men were announced as the prime crew of Apollo 16 on March 3, 1971.

Apollo 16's backup crew consisted of Fred W. Haise Jr. (commander, who had flown on Apollo 13), Stuart A. Roosa (CMP, who had flown on Apollo 14

Apollo 14 (January 31, 1971February 9, 1971) was the eighth crewed mission in the United States Apollo program, the third to land on the Moon, and the first to land in the lunar highlands. It was the last of the " H missions", landings at ...

) and Edgar D. Mitchell (LMP, also Apollo 14). Although not officially announced, Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton

Donald Kent "Deke" Slayton (March 1, 1924 – June 13, 1993) was a United States Air Force pilot, aeronautical engineer, and test pilot who was selected as one of the original NASA Mercury Seven astronauts. He went on to become NASA's fir ...

, the astronauts' supervisor, had originally planned to have a backup crew of Haise as commander, William R. Pogue

William Reid Pogue (January 23, 1930 – March 3, 2014) was an American astronaut and pilot who served in the United States Air Force (USAF) as a fighter pilot and test pilot, and reached the rank of colonel. He was also a teacher, public speak ...

(CMP) and Gerald P. Carr (LMP), who were targeted for the prime crew assignment on Apollo 19. However, after the cancellations of Apollos 18 and 19 were announced in September 1970, it made more sense to use astronauts who had already flown lunar missions as backups, rather than training others on what would likely be a dead-end assignment. Subsequently, Roosa and Mitchell were assigned to the backup crew, while Pogue and Carr were reassigned to the Skylab

Skylab was the first United States space station, launched by NASA, occupied for about 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. It was operated by three separate three-astronaut crews: Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4. Major operations ...

program where they flew on Skylab 4

Skylab 4 (also SL-4 and SLM-3) was the third crewed Skylab mission and placed the third and final crew aboard the first American space station.

The mission began on November 16, 1973, with the launch of Gerald P. Carr, Edward Gibson, and Wil ...

.

For projects Mercury and Gemini, a prime and a backup crew had been designated, but for Apollo, a third group of astronauts, known as the support crew, was also designated. Slayton created the support crews early in the Apollo Program on the advice of Apollo crew commander James McDivitt

James Alton McDivitt (June 10, 1929 – October 13, 2022) was an American test pilot, United States Air Force (USAF) pilot, aeronautical engineer, and NASA astronaut in the Gemini and Apollo programs. He joined the USAF in 1951 and flew 1 ...

, who would lead Apollo 9. McDivitt believed that, with preparation going on in facilities across the U.S., meetings that needed a member of the flight crew would be missed. Support crew members were to assist as directed by the mission commander. Usually low in seniority, they assembled the mission's rules, flight plan

Flight plans are documents filed by a pilot or flight dispatcher with the local Air Navigation Service Provider (e.g. the FAA in the United States) prior to departure which indicate the plane's planned route or flight path. Flight plan forma ...

, and checklists, and kept them updated. For Apollo 16, they were: Anthony W. England

Anthony Wayne England (born May 15, 1942), better known as Tony England, is an American, former NASA astronaut. Selected in 1967, England was among a group of astronauts who served as backups during the Apollo and Skylab programs. Like most ot ...

, Karl G. Henize, Henry W. Hartsfield Jr., Robert F. Overmyer

Colonel Robert Franklyn "Bob" Overmyer (July 14, 1936 – March 22, 1996) was an American test pilot, naval aviator, aeronautical engineer, physicist, United States Marine Corps officer, and USAF/NASA astronaut. Overmyer was selected by the Air ...

and Donald H. Peterson

Donald Herod Peterson (October 22, 1933 – May 27, 2018) was a United States Air Force officer and NASA astronaut. Peterson was originally selected for the Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, but, when that was canceled, h ...

.

Flight directors were Pete Frank

Pete Frank, also known as M. P. Frank III (August 20, 1930June 22, 2005) was a NASA engineer who served as the lead flight director for the Apollo 14 and Apollo 16 crewed lunar landing missions, as well as the American lead flight director fo ...

and Philip Shaffer, first shift, Gene Kranz

Eugene Francis "Gene" Kranz (born August 17, 1933) is an American aerospace engineer who served as NASA's second Chief Flight Director, directing missions of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs, including the first lunar landing mission, Ap ...

and Donald R. Puddy, second shift, and Gerry Griffin, Neil B. Hutchinson and Charles R. Lewis, third shift. Flight directors during Apollo had a one-sentence job description: "The flight director may take any actions necessary for crew safety and mission success." CAPCOM

is a Japanese video game developer and publisher. It has created a number of multi-million-selling game franchises, with its most commercially successful being '' Resident Evil'', '' Monster Hunter'', '' Street Fighter'', ''Mega Man'', ''De ...

s were Haise, Roosa, Mitchell, James B. Irwin, England, Peterson, Hartsfield, and C. Gordon Fullerton.

Mission insignia and call signs

The insignia of Apollo 16 is dominated by a rendering of an

The insignia of Apollo 16 is dominated by a rendering of an American eagle

The bald eagle (''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') is a bird of prey found in North America. A sea eagle, it has two known subspecies and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), which occupies the same niche as ...

and a red, white and blue shield, representing the people of the United States, over a gray background representing the lunar surface. Overlaying the shield is a gold NASA vector, orbiting the Moon. On its gold-outlined blue border, there are 16 stars, representing the mission number, and the names of the crew members: Young, Mattingly, Duke. The insignia was designed from ideas originally submitted by the crew of the mission, by Barbara Matelski of the graphics shop at the Manned Spacecraft Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

in Houston.

Young and Duke chose "Orion" for the lunar module's call sign, while Mattingly chose "Casper" for the command and service module. According to Duke, he and Young chose "Orion" for the LM because they wanted something connected with the stars. Orion is one of the brightest constellations as seen from Earth, and one visible to the astronauts throughout their journey. Duke also stated, "it is a prominent constellation and easy to pronounce and transmit to Mission Control". Mattingly said he chose "Casper", evoking Casper the Friendly Ghost

Casper the Friendly Ghost is the protagonist of the Famous Studios theatrical animated cartoon series of the same name. He is a pleasant, personable and translucent ghost, but often criticized by his three wicked uncles, the Ghostly Trio.

The ...

, because "there are enough serious things in this flight, so I picked a non-serious name."

Planning and training

Landing site selection

Apollo 16 was the second of Apollo's J missions, featuring the use of theLunar Roving Vehicle

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) is a battery-powered four-wheeled rover used on the Moon in the last three missions of the American Apollo program ( 15, 16, and 17) during 1971 and 1972. It is popularly called the Moon buggy, a play on the ...

, increased scientific capability, and three-day lunar surface stays. As Apollo 16 was the penultimate mission in the Apollo program and there was no major new hardware or procedures to test on the lunar surface, the last two missions (the other being Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walke ...

) presented opportunities for astronauts to clear up some of the uncertainties in understanding the Moon's characteristics. Scientists sought information on the Moon's early history, which might be obtained from its ancient surface features, the lunar highlands

The geology of the Moon (sometimes called selenology, although the latter term can refer more generally to " lunar science") is quite different from that of Earth. The Moon lacks a true atmosphere, which eliminates erosion due to weather. It does ...

. Previous Apollo expeditions, including Apollo 14 and Apollo 15

Apollo 15 (July 26August 7, 1971) was the ninth crewed mission in the United States' Apollo program and the fourth to land on the Moon. It was the first J mission, with a longer stay on the Moon and a greater focus on science than ear ...

, had obtained samples of pre-mare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than fo ...

lunar material, likely thrown from the highlands by meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object ...

impacts. These were dated from before lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or ...

began to upwell from the Moon's interior and flood the low areas and basins. Nevertheless, no Apollo mission had actually visited the lunar highlands.

Apollo 14 had visited and sampled a ridge of material ejected by the impact that created the Mare Imbrium impact basin. Likewise, Apollo 15 had also sampled material in the region of Imbrium, visiting the basin's edge. Because the Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 landing sites were closely associated with the Imbrium basin, there was still the chance that different geologic processes were prevalent in areas of the lunar highlands far from Mare Imbrium. Scientist Dan Milton, studying photographs of the highlands from Lunar Orbiter photographs, saw an area in the Descartes region of the Moon with unusually high albedo that he theorized might be due to volcanic rock

Volcanic rock (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) is a rock formed from lava erupted from a volcano. In other words, it differs from other igneous rock by being of volcanic origin. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic ...

; his theory quickly gained wide support. Several members of the scientific community noted that the central lunar highlands resembled regions on Earth that were created by volcanism processes and hypothesized the same might be true on the Moon. They hoped scientific output from the Apollo 16 mission would provide an answer. Some scientists advocated for a landing near the large crater, Tycho, but its distance from the lunar equator and the fact that the lunar module would have to approach over very rough terrain ruled it out.

The Ad Hoc Apollo Site Evaluation Committee met in April and May 1971 to decide the Apollo 16 and 17 landing sites; it was chaired by

The Ad Hoc Apollo Site Evaluation Committee met in April and May 1971 to decide the Apollo 16 and 17 landing sites; it was chaired by Noel Hinners

Noel William Hinners (December 25, 1935 – September 5, 2014) was an American geologist and soil chemist who is primarily remembered for his work with NASA where he worked in a variety of scientific and administrative roles from 1963 to 1989, i ...

of Bellcomm

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

. There was consensus the final landing sites should be in the lunar highlands, and among the sites considered for Apollo 16 were the Descartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after ...

region west of Mare Nectaris

Mare Nectaris (Latin ''nectaris'', the "Sea of Nectar") is a small lunar mare or sea (a volcanic lava plain noticeably darker than the rest of the Moon's surface) located south of Mare Tranquillitatis southwest of Mare Fecunditatis, on the near ...

and the crater Alphonsus. The considerable distance between the Descartes site and previous Apollo landing sites would also be beneficial for the network of seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outpu ...

s, deployed on each landing mission beginning with Apollo 12.

At Alphonsus, three scientific objectives were determined to be of primary interest and paramount importance: the possibility of old, pre-Imbrium impact material from within the crater's wall, the composition of the crater's interior and the possibility of past volcanic activity on the floor of the crater at several smaller "dark halo" craters. Geologists feared, however, that samples obtained from the crater might have been contaminated by the Imbrium impact, thus preventing Apollo 16 from obtaining samples of pre-Imbrium material. There also remained the distinct possibility that this objective would have already been satisfied by the Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 missions, as the Apollo 14 samples had not yet been completely analyzed and samples from Apollo 15 had not yet been obtained.

On June 3, 1971, the site selection committee decided to target the Apollo 16 mission for the Descartes site. Following the decision, the Alphonsus site was considered the most likely candidate for Apollo 17, but was eventually rejected. With the assistance of orbital photography obtained on the Apollo 14 mission, the Descartes site was determined to be safe enough for a crewed landing. The specific landing site was between two young impact craters, North Ray and South Ray craters – in diameter, respectively – which provided "natural drill holes" which penetrated through the lunar regolith

Regolith () is a blanket of unconsolidated, loose, heterogeneous superficial deposits covering solid rock. It includes dust, broken rocks, and other related materials and is present on Earth, the Moon, Mars, some asteroids, and other terrestr ...

at the site, thus leaving exposed bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid rock that lies under loose material ( regolith) within the crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface material. An exposed portion of be ...

that could be sampled by the crew.

After the selection, mission planners made the Descartes and Cayley formations, two geologic units of the lunar highlands, the primary sampling interest of the mission. It was these formations that the scientific community widely suspected were formed by lunar volcanism, but this hypothesis was proven incorrect by the composition of lunar samples from the mission.

Training

In addition to the usual Apollo spacecraft training, Young and Duke, along with backup commander Fred Haise, underwent an extensive

In addition to the usual Apollo spacecraft training, Young and Duke, along with backup commander Fred Haise, underwent an extensive geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

training program that included several field trips to introduce them to concepts and techniques they would use in analyzing features and collecting samples on the lunar surface. During these trips, they visited and provided scientific descriptions of geologic features they were likely to encounter. The backup LMP, Mitchell, was unavailable during the early part of the training, occupied with tasks relating to Apollo 14, but by September 1971 had joined the geology field trips. Before that, Tony England (a member of the support crew and the lunar EVA CAPCOM) or one of the geologist trainers would train alongside Haise on geology field trips.

Since Descartes was believed to be volcanic, a good deal of this training was geared towards volcanic rocks and features, but field trips were made to sites featuring other sorts of rock. As Young later commented, the non-volcanic training proved more useful, given that Descartes did not prove to be volcanic. In July 1971, they visited Sudbury Sudbury may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sudbury Reef, Queensland

Canada

* Greater Sudbury, Ontario (official name; the city continues to be known simply as Sudbury for most purposes)

** Sudbury (electoral district), one of the city's federal el ...

, Ontario, Canada, for geology training exercises, the first time U.S. astronauts trained in Canada. The Apollo 14 landing crew had visited a site in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

; geologist Don Wilhelms related that unspecified incidents there had caused Slayton to rule out further European training trips. Geologists chose Sudbury because of a wide crater created about 1.8 billion years ago by a large meteorite. The Sudbury Basin

The Sudbury Basin (), also known as Sudbury Structure or the Sudbury Nickel Irruptive, is a major geological structure in Ontario, Canada. It is the third-largest known impact crater or astrobleme on Earth, as well as one of the oldest. The ...

shows evidence of shatter cone

Shatter cones are rare geological features that are only known to form in the bedrock beneath meteorite impact craters or underground nuclear explosions. They are evidence that the rock has been subjected to a shock with pressures in the rang ...

geology, familiarizing the Apollo crew with geologic evidence of a meteorite impact. During the training exercises the astronauts did not wear space suits

A space suit or spacesuit is a garment worn to keep a human alive in the harsh environment of outer space, vacuum and temperature extremes. Space suits are often worn inside spacecraft as a safety precaution in case of loss of cabin pressure, ...

, but carried radio equipment to converse with each other and England, practicing procedures they would use on the lunar surface. By the end of the training, the field trips had become major exercises, involving up to eight astronauts and dozens of support personnel, attracting coverage from the media. For the exercise at the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the ...

, where the massive craters left by nuclear explosions simulated the large craters to be found on the Moon, all participants had to have security clearance and a listed next-of-kin, and an overflight by CMP Mattingly required special permission.

In addition to the field geology training, Young and Duke also trained to use their EVA space suits, adapt to the reduced lunar gravity, collect samples, and drive the Lunar Roving Vehicle. The fact that they had been backups for Apollo 13, planned to be a landing mission, meant that they could spend about 40 percent of their time training for their surface operations. They also received survival training and prepared for technical aspects of the mission. The astronauts spent much time studying the lunar samples brought back by earlier missions, learning about the instruments to be carried on the mission, and hearing what the principal investigators in charge of those instruments expected to learn from Apollo 16. This training helped Young and Duke, while on the Moon, quickly realize that the expected volcanic rocks were not there, even though the geologists in Mission Control initially did not believe them. Much of the training—according to Young, 350 hours—was conducted with the crew wearing space suits, something that Young deemed vital, allowing the astronauts to know the limitations of the equipment in doing their assigned tasks. Mattingly also received training in recognizing geological features from orbit by flying over the field areas in an airplane, and trained to operate the Scientific Instrument Module from lunar orbit.

In addition to the field geology training, Young and Duke also trained to use their EVA space suits, adapt to the reduced lunar gravity, collect samples, and drive the Lunar Roving Vehicle. The fact that they had been backups for Apollo 13, planned to be a landing mission, meant that they could spend about 40 percent of their time training for their surface operations. They also received survival training and prepared for technical aspects of the mission. The astronauts spent much time studying the lunar samples brought back by earlier missions, learning about the instruments to be carried on the mission, and hearing what the principal investigators in charge of those instruments expected to learn from Apollo 16. This training helped Young and Duke, while on the Moon, quickly realize that the expected volcanic rocks were not there, even though the geologists in Mission Control initially did not believe them. Much of the training—according to Young, 350 hours—was conducted with the crew wearing space suits, something that Young deemed vital, allowing the astronauts to know the limitations of the equipment in doing their assigned tasks. Mattingly also received training in recognizing geological features from orbit by flying over the field areas in an airplane, and trained to operate the Scientific Instrument Module from lunar orbit.

Equipment

Launch vehicle

The launch vehicle which took Apollo 16 to the Moon was aSaturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

, designated as AS-511. This was the eleventh Saturn V to be flown and the ninth used on crewed missions. Apollo 16's Saturn V was almost identical to Apollo 15's. One change that was made was the restoration of four retrorocket

A retrorocket (short for ''retrograde rocket'') is a rocket engine providing thrust opposing the motion of a vehicle, thereby causing it to decelerate. They have mostly been used in spacecraft, with more limited use in short-runway aircraft land ...

s to the S-IC

The S-IC (pronounced S-one-C) was the first stage of the American Saturn V rocket. The S-IC stage was manufactured by the Boeing Company. Like the first stages of most rockets, most of its mass of more than at launch was propellant, in this cas ...

first stage, meaning there would be a total of eight, as on Apollo 14 and earlier. The retrorockets were used to minimize the risk of collision between the jettisoned first stage and the Saturn V. These four retrorockets had been omitted from Apollo 15's Saturn V to save weight, but analysis of Apollo 15's flight showed that the S-IC came closer than expected after jettison, and it was feared that if there were only four rockets and one failed, there might be a collision.

ALSEP and other surface equipment

As on all lunar landing missions after Apollo 11, anApollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package

The Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) comprised a set of scientific instruments placed by the astronauts at the landing site of each of the five Apollo missions to land on the Moon following Apollo 11 (Apollos 12, 14, 15, 16, ...

(ALSEP) was flown on Apollo 16. This was a suite of nuclear-powered experiments designed to keep functioning after the astronauts who set them up returned to Earth. Apollo 16's ALSEP consisted of a Passive Seismic Experiment (PSE, a seismometer), an Active Seismic Experiment (ASE), a Lunar Heat Flow Experiment (HFE), and a Lunar Surface Magnetometer (LSM). The ALSEP was powered by a SNAP-27

The Systems Nuclear Auxiliary POWER (SNAP) program was a program of experimental radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and space nuclear reactors flown during the 1960s by NASA.

Odd-numbered SNAPs: radioisotope thermoelectric generator ...

radioisotope thermoelectric generator

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG, RITEG), sometimes referred to as a radioisotope power system (RPS), is a type of nuclear battery that uses an array of thermocouples to convert the heat released by the decay of a suitable radioa ...

, developed by the Atomic Energy Commission.

The PSE added to the network of seismometers left by Apollo 12, 14 and 15. NASA intended to calibrate the Apollo 16 PSE by crashing the LM's ascent stage near it after the astronauts were done with it, an object of known mass and velocity impacting at a known location. However, NASA lost control of the ascent stage after jettison, and this did not occur. The ASE, designed to return data about the Moon's geologic structure, consisted of two groups of explosives: one, a line of "thumpers" were to be deployed attached to three

The PSE added to the network of seismometers left by Apollo 12, 14 and 15. NASA intended to calibrate the Apollo 16 PSE by crashing the LM's ascent stage near it after the astronauts were done with it, an object of known mass and velocity impacting at a known location. However, NASA lost control of the ascent stage after jettison, and this did not occur. The ASE, designed to return data about the Moon's geologic structure, consisted of two groups of explosives: one, a line of "thumpers" were to be deployed attached to three geophone

A geophone is a device that converts ground movement (velocity) into voltage, which may be recorded at a recording station. The deviation of this measured voltage from the base line is called the seismic response and is analyzed for structure of ...

s. The thumpers would be exploded during the ALSEP deployment. A second group was four mortars of different sizes, to be set off remotely once the astronauts had returned to Earth. Apollo 14 had also carried an ASE, though its mortars were never set off for fear of affecting other experiments.

The HFE involved the drilling of two holes into the lunar surface and emplacement of thermometers which would measure how much heat was flowing from the lunar interior. This was the third attempt to emplace a HFE: the first flew on Apollo 13 and never reached the lunar surface, while on Apollo 15, problems with the drill meant the probes did not go as deep as planned. The Apollo 16 attempt would fail after Duke had successfully emplaced the first probe; Young, unable to see his feet in the bulky spacesuit, pulled out and severed the cable after it wrapped around his leg. NASA managers vetoed a repair attempt due to the amount of time it would take. A HFE flew, and was successfully deployed, on Apollo 17.

The LSM was designed to measure the strength of the Moon's

The LSM was designed to measure the strength of the Moon's magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

, which is only a small fraction of Earth's. Additional data would be returned by the use of the Lunar Portable Magnetometer (LPM), to be carried on the lunar rover and activated at several geology stops. Scientists also hoped to learn from an Apollo 12 sample, to be briefly returned to the Moon on Apollo 16, from which "soft" magnetism had been removed, to see if it had been restored on its journey. Measurements after the mission found that "soft" magnetism had returned to the sample, although at a lower intensity than before.

A Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph

The Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph (UVC) was one of the experiments deployed on the lunar surface by the Apollo 16 astronauts. It consisted of a telescope and camera that obtained astronomical images and spectra in the far ultraviolet region ...

(UVC) was flown, the first astronomical observations taken from the Moon, seeking data on hydrogen sources in space without the masking effect of the Earth's corona. The instrument was placed in the LM's shadow and pointed at nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regio ...

e, other astronomical objects, the Earth itself, and any suspected volcanic vents seen on the lunar surface. The film was returned to Earth. When asked to summarize the results for a general audience, Dr. George Carruthers

George Robert Carruthers (October 1, 1939 – December 26, 2020) was an African American inventor, physicist, engineer and space scientist. Carruthers perfected a compact and very powerful Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph, ultraviolet camera/s ...

of the Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. It was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, applied research, technologic ...

stated, "the most immediately obvious and spectacular results were really for the Earth observations, because this was the first time that the Earth had been photographed from a distance in ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

(UV) light, so that you could see the full extent of the hydrogen atmosphere, the polar auroris and what we call the tropical airglow belt."

Four panels mounted on the LM's descent stage comprised the Cosmic Ray Detector, designed to record cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

and solar wind

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles released from the upper atmosphere of the Sun, called the corona. This plasma mostly consists of electrons, protons and alpha particles with kinetic energy between . The composition of the sol ...

particles. Three of the panels were left uncovered during the voyage to the Moon, with the fourth uncovered by the crew early in the EVA. The panels would be bagged for return to Earth. The free-standing Solar Wind Composition Experiment flew on Apollo 16, as it had on each of the lunar landings, for deployment on the lunar surface and return to Earth. Platinum foil was added to the aluminum of the previous experiments, to minimize contamination.

Particles and Fields Subsatellite PFS-2

The Apollo 16 Particles and Fields Subsatellite (PFS-2) was a small satellite released into lunar orbit from the service module. Its principal objective was to measure charged particles and magnetic fields all around the Moon as the Moon orbited Earth, similar to its sister spacecraft,PFS-1

Apollo 15 (July 26August 7, 1971) was the ninth crewed mission in the United States' Apollo program and the fourth to land on the Moon. It was the first J mission, with a longer stay on the Moon and a greater focus on science than ear ...

, released eight months earlier by Apollo 15. The two probes were intended to have similar orbits, ranging from above the lunar surface.

Like the Apollo 15 subsatellite, PFS-2 was expected to have a lifetime of at least a year before its orbit decayed and it crashed onto the lunar surface. The decision to bring Apollo 16 home early after there were difficulties with the main engine meant that the spacecraft did not go to the orbit which had been planned for PFS-2. Instead, it was ejected into a lower-than-planned orbit and crashed into the Moon a month later on May 29, 1972, after circling the Moon 424 times. This brief lifetime was because lunar mascons were near to its orbital ground track and helped pull PFS-2 into the Moon.

Mission events

Elements of the spacecraft and launch vehicle began arriving atKennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten field centers. Since December 196 ...

in July 1970, and all had arrived by September 1971. Apollo 16 was originally scheduled to launch on March 17, 1972. One of the bladders for the CM's reaction control system

A reaction control system (RCS) is a spacecraft system that uses thrusters to provide attitude control and translation. Alternatively, reaction wheels are used for attitude control. Use of diverted engine thrust to provide stable attitude con ...

burst during testing. This issue, in combination with concerns that one of the explosive cords that would jettison the LM from the CSM after the astronauts returned from the lunar surface would not work properly, and a problem with Duke's spacesuit, made it desirable to slip the launch to the next launch window

In the context of spaceflight, launch period is the collection of days and launch window is the time period on a given day during which a particular rocket must be launched in order to reach its intended target. If the rocket is not launched wi ...

. Thus, Apollo 16 was postponed to April 16. The launch vehicle stack, which had been rolled out from the Vehicle Assembly Building

The Vehicle Assembly Building (originally the Vertical Assembly Building), or VAB, is a large building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC), designed to assemble large pre-manufactured space vehicle components, such as the massive Saturn V and t ...

on December 13, 1971, was returned thereto on January 27, 1972. It was rolled out again to Launch Complex 39A on February 9.

The official mission countdown began on Monday, April 10, 1972, at 8:30 am, six days before the launch. At this point the SaturnV rocket's three stages were powered up, and drinking water was pumped into the spacecraft. As the countdown began, the crew of Apollo 16 was participating in final training exercises in anticipation of a launch on April 16. The astronauts underwent their final preflight physical examination on April 11. The only holds in the countdown were the ones pre-planned in the schedule, and the weather was fair as the time for launch approached.

Launch and outward journey

The Apollo 16 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 pm EST on April 16, 1972. The launch was nominal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that on previous missions. The first and second stages of the SaturnV (the S-IC and

The Apollo 16 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 pm EST on April 16, 1972. The launch was nominal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that on previous missions. The first and second stages of the SaturnV (the S-IC and S-II

The S-II (pronounced "S-two") was the second stage of the Saturn V rocket. It was built by North American Aviation. Using LH2, liquid hydrogen (LH2) and liquid oxygen (LOX) it had five J-2 (rocket engine), J-2 engines in a quincunx pattern. The ...

) performed nominally; the spacecraft entered orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

around Earth just under 12 minutes after lift-off.

After reaching orbit, the crew spent time adapting to the zero-gravity

Weightlessness is the complete or near-complete absence of the sensation of weight. It is also termed zero gravity, zero G-force, or zero-G.

Weight is a measurement of the force on an object at rest in a relatively strong gravitational fie ...

environment and preparing the spacecraft for trans-lunar injection

A trans-lunar injection (TLI) is a propulsive maneuver used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory that will cause it to arrive at the Moon.

History

The first space probe to attempt TLI was the Soviet Union's Luna 1 on January 2, 1959 which w ...

(TLI), the burn of the third-stage rocket that would propel them to the Moon. In Earth orbit, the crew faced minor technical issues, including a potential problem with the environmental control system and the S-IVB

The S-IVB (pronounced "S-four-B") was the third stage on the Saturn V and second stage on the Saturn IB launch vehicles. Built by the Douglas Aircraft Company, it had one J-2 rocket engine. For lunar missions it was fired twice: first for Earth ...

third stage's attitude control system, but eventually resolved or compensated for them as they prepared to depart towards the Moon.

After two orbits, the rocket's third stage reignited for just over five minutes, propelling the craft towards the Moon at about . Six minutes after the burn of the S-IVB, the command and service modules (CSM), containing the crew, separated from the rocket and traveled away from it before turning around and retrieving the lunar module from inside the expended rocket stage. The maneuver, performed by Mattingly and known as transposition, docking, and extraction

Transposition, docking, and extraction (often abbreviated to transposition and docking) was a maneuver performed during Apollo lunar landing missions from 1969 to 1972, to withdraw the Apollo Lunar Module (LM) from its adapter housing which sec ...

, went smoothly.

Following transposition and docking, the crew noticed the exterior surface of the lunar module was giving off particles from a spot where the LM's skin appeared torn or shredded; at one point, Duke estimated they were seeing about five to ten particles per second. Young and Duke entered the lunar module through the docking tunnel connecting it with the command module to inspect its systems, at which time they did not spot any major issues.

Once on course towards the Moon, the crew put the spacecraft into a rotisserie "barbecue" mode in which the craft rotated along its long axis three times per hour to ensure even heat distribution about the spacecraft from the Sun. After further preparing the craft for the voyage, the crew began the first sleep period of the mission just under 15 hours after launch.

By the time Mission Control issued the wake-up call to the crew for flight day two, the spacecraft was about away from the Earth, traveling at about . As it was not due to arrive in lunar orbit until flight day four, flight days two and three were largely preparatory, consisting of spacecraft maintenance and scientific research. On day two, the crew performed an

By the time Mission Control issued the wake-up call to the crew for flight day two, the spacecraft was about away from the Earth, traveling at about . As it was not due to arrive in lunar orbit until flight day four, flight days two and three were largely preparatory, consisting of spacecraft maintenance and scientific research. On day two, the crew performed an electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fi ...

experiment, also performed on Apollo 14, in which they attempted to demonstrate that electrophoretic separation in their near-weightless environment could be used to produce substances of greater purity than would be possible on Earth. Using two different sizes of polystyrene

Polystyrene (PS) is a synthetic polymer made from monomers of the Aromatic hydrocarbon, aromatic hydrocarbon styrene. Polystyrene can be solid or foamed. General-purpose polystyrene is clear, hard, and brittle. It is an inexpensive resin pe ...

particles, one size colored red and one blue, separation of the two types via electrophoresis was achieved, though electro-osmosis in the experiment equipment prevented the clear separation of two particle bands.

The remainder of day two included a two-second mid-course correction burn performed by the CSM's service propulsion system

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother shi ...

(SPS) engine to tweak the spacecraft's trajectory. Later in the day, the astronauts entered the lunar module for the second time to further inspect the landing craft's systems. The crew reported they had observed additional paint peeling from a portion of the LM's outer aluminum skin. Despite this, the crew discovered that the spacecraft's systems were performing nominally. Following the LM inspection, the crew reviewed checklists and procedures for the following days in anticipation of their arrival and the Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn. Command Module Pilot Mattingly reported "gimbal lock

Gimbal lock is the loss of one degree of freedom in a three-dimensional, three-gimbal mechanism that occurs when the axes of two of the three gimbals are driven into a parallel configuration, "locking" the system into rotation in a degenerate t ...

", meaning that the system to keep track of the craft's attitude

Attitude may refer to:

Philosophy and psychology

* Attitude (psychology), an individual's predisposed state of mind regarding a value

* Metaphysics of presence

* Propositional attitude, a relational mental state connecting a person to a propo ...

was no longer accurate. Mattingly had to realign the guidance system using the Sun and Moon. At the end of day two, Apollo 16 was about away from Earth.

When the astronauts were awakened for flight day three, the spacecraft was about away from the Earth. The velocity of the craft steadily decreased, as it had not yet reached the lunar sphere of gravitational influence. The early part of day three was largely housekeeping, spacecraft maintenance and exchanging status reports with Mission Control in Houston. The crew performed the Apollo light flash experiment, or ALFMED, to investigate "light flashes" that were seen by Apollo lunar astronauts when the spacecraft was dark, regardless of whether their eyes were open. This was thought to be caused by the penetration of the eye by cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

particles. During the second half of the day, Young and Duke again entered the lunar module to power it up and check its systems, and perform housekeeping tasks in preparation for the lunar landing. The systems were found to be functioning as expected. Following this, the crew donned their space suits and rehearsed procedures that would be used on landing day. Just before the end of flight day three at 59 hours, 19 minutes, 45 seconds after liftoff, while from the Earth and from the Moon, the spacecraft's velocity began increasing as it accelerated towards the Moon after entering the lunar sphere of influence.

After waking up on flight day four, the crew began preparations for the LOI maneuver that would brake them into orbit. At an altitude of the scientific instrument module

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo (spacecraft), Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functio ...

(SIM) bay cover was jettisoned. At just over 74 hours into the mission, the spacecraft passed behind the Moon, temporarily losing contact with Mission Control. While over the far side

''The Far Side'' is a single-panel comic created by Gary Larson and syndicated by Chronicle Features and then Universal Press Syndicate, which ran from December 31, 1979, to January 1, 1995 (when Larson retired as a cartoonist). Its surrealist ...

, the SPS burned for 6minutes and 15 seconds, braking the spacecraft into an orbit with a low point (pericynthion) of 58.3 and a high point (apocynthion) of 170.4 nautical miles (108.0 and 315.6 km, respectively). After entering lunar orbit, the crew began preparations for the Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI) maneuver to further modify the spacecraft's orbital trajectory. The maneuver was successful, decreasing the craft's pericynthion to . The remainder of flight day four was spent making observations and preparing for activation of the lunar module, undocking, and landing the following day.

Lunar surface

The crew continued preparing for lunar module activation and undocking shortly after waking up to begin flight day five. The boom that extended the

The crew continued preparing for lunar module activation and undocking shortly after waking up to begin flight day five. The boom that extended the mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

in the SIM bay was stuck, semi-deployed. It was decided that Young and Duke would visually inspect the boom after undocking the LM from the CSM. They entered the LM for activation and checkout of the spacecraft's systems. Despite entering the LM 40 minutes ahead of schedule, they completed preparations only 10 minutes early due to numerous delays in the process. With the preparations finished, they undocked 96 hours, 13 minutes, 31 seconds into the mission.

For the rest of the two crafts' passes over the near side of the Moon

The near side of the Moon is the lunar hemisphere that always faces towards Earth, opposite to the far side. Only one side of the Moon is visible from Earth because the Moon rotates on its axis at the same rate that the Moon orbits the Earth—a ...

, Mattingly prepared to shift ''Casper'' to a higher, near-circular orbit, while Young and Duke prepared ''Orion'' for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, Mattingly detected oscillations in the SPS engine's backup gimbal system. According to mission rules, under such circumstances, ''Orion'' was to re-dock with ''Casper'', in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use the lunar module's engines for the return trip to Earth. Instead, the two craft kept station, maintaining positions close to each other. After several hours of analysis, mission controllers determined that the malfunction could be worked around, and Young and Duke could proceed with the landing.

Powered descent to the lunar surface began about six hours behind schedule. Because of the delay, Young and Duke began their descent to the surface at an altitude higher than that of any previous mission, at . After descending to an altitude of about , Young was able to view the landing site in its entirety. Throttle-down of the LM's landing engine occurred on time, and the spacecraft tilted forward to its landing orientation at an altitude of . The LM landed north and west of the planned landing site at 104 hours, 29 minutes, and 35 seconds into the mission, at 2:23:35 UTC on April 21 (8:23:35 pm on April 20 in Houston). The availability of the Lunar Roving Vehicle

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) is a battery-powered four-wheeled rover used on the Moon in the last three missions of the American Apollo program ( 15, 16, and 17) during 1971 and 1972. It is popularly called the Moon buggy, a play on the ...

rendered their distance from the targeted point trivial.