Antiochus I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Antiochus I Soter ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Σωτήρ, ''Antíochos Sōtér''; "Antiochus the Saviour"; c. 324/32 June 261 BC) was a

Recent analysis strongly suggests that the city of

Recent analysis strongly suggests that the city of

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenic kings:

Alternatively, the Greek king mentioned in the Edict of Ashoka could also be Antiochus's son and successor,

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenic kings:

Alternatively, the Greek king mentioned in the Edict of Ashoka could also be Antiochus's son and successor,

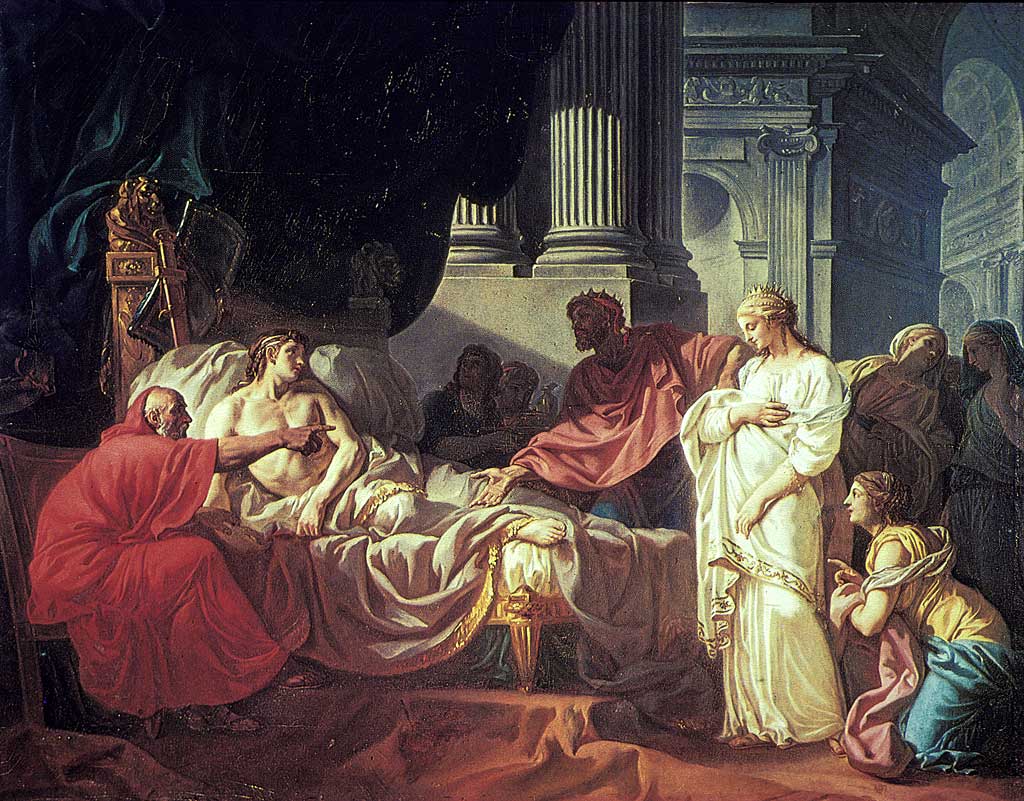

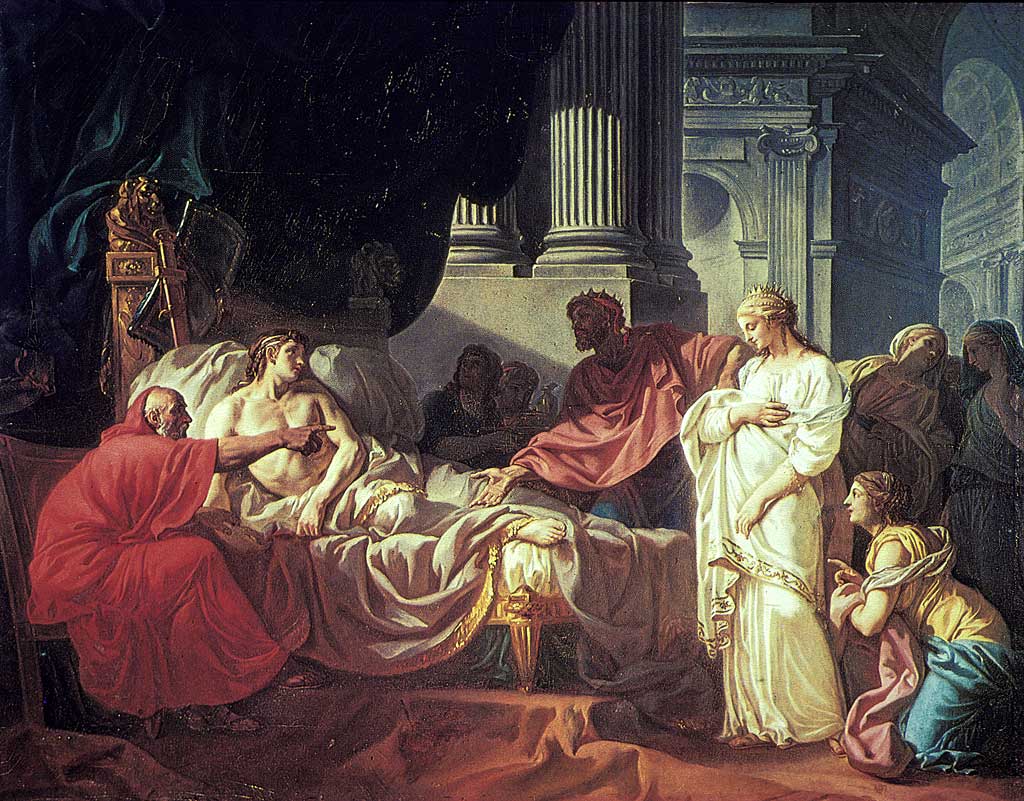

The love between Antiochus and his stepmother Stratonice was often depicted in

The love between Antiochus and his stepmother Stratonice was often depicted in

Appianus' ''Syriaka''

fact sheet at Livius.org

Babylonian Chronicles of the Hellenic Period

entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

Hellenization of the Babylonian Culture?

{{DEFAULTSORT:Antiochus 01 Soter 320s BC births 261 BC deaths Year of birth uncertain 3rd-century BC Babylonian kings 3rd-century BC Seleucid rulers Antiochus 01 3rd-century BC rulers Kings of the Universe Kings of the Lands

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

in 281 BC and reigned during a period of instability which he mostly overcame until his death on 2 June 261 BC. He is the last known ruler to be attributed the ancient Mesopotamian title King of the Universe.

Biography

Antiochus's father wasSeleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

and his mother was Apama

Apama ( grc, Ἀπάμα, Apáma), sometimes known as Apama I or Apame I, was a Sogdian noblewoman and the wife of the first ruler of the Seleucid Empire, Seleucus I Nicator. They Susa weddings, married at Susa in 324 BC. According to Arrian, Apa ...

, daughter of Spitamenes

Spitamenes (Old Persian ''Spitamana''; Greek ''Σπιταμένης''; 370 BC – 328 BC) was a Sogdian warlordHolt, Frank L. (1989), ''Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia'', Leiden, New York, Cope ...

, being one of the princesses whom Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

had given as wives to his generals in 324 BC. The Seleucids fictitiously claimed that Apama was the daughter of Darius III, in order to legitimise themselves as the inheritors of both the Achaemenids and Alexander, and therefore the rightful lords of western and central Asia.

In 294 BC, prior to the death of his father Seleucus I

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the pow ...

, Antiochus married his stepmother, Stratonice, daughter of Demetrius Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

. The ancient sources report that his elderly father reportedly instigated the marriage after discovering that his son was in danger of dying of lovesickness

Lovesickness refers to an affliction that can produce negative feelings when deeply in love, during the absence of a loved one or when love is unrequited.

The term "lovesickness" is rarely used in modern medicine and psychology, though new rese ...

. Stratonice bore five children to Antiochus: Seleucus (later executed for rebellion), Laodice, Apama II

Apama ( grc, Ἀπάμα, Apáma), sometimes known as Apama I or Apame I, was a Sogdian noblewoman and the wife of the first ruler of the Seleucid Empire, Seleucus I Nicator. They married at Susa in 324 BC. According to Arrian, Apama was the ...

, Stratonice II and Antiochus II Theos

Antiochus II Theos ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Θεός, ; 286 – July 246 BC) was a Greek king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire who reigned from 261 to 246 BC. He succeeded his father Antiochus I Soter in the winter of 262–61 BC. He wa ...

, who succeeded his father as king.

The ''Ruin of Esagila Chronicle'', dated between 302 and 281 BC, mentions that a crown prince, most likely Antiochus, decided to rebuild the ruined Babylonian temple Esagila

The Ésagila or Esangil ( sux, , ''"temple whose top is lofty"'') was a temple dedicated to Marduk, the protector god of Babylon. It lay south of the ziggurat Etemenanki.

Description

In this temple was the statue of Marduk, surrounded by cu ...

, and made a sacrifice in preparation. However, while there, he stumbled on the rubble and fell. He then ordered his troops to destroy the last of the remains.

On the assassination of his father in 281 BC, the task of holding together the empire was a formidable one. A revolt in Syria broke out almost immediately. Antiochus was soon compelled to make peace with his father's murderer, Ptolemy Keraunos

Ptolemy Ceraunus ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Κεραυνός ; c. 319 BC – January/February 279 BC) was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty and briefly king of Macedon. As the son of Ptolemy I Soter, he was originally heir to the thron ...

, apparently abandoning Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an Classical antiquity, ancient monarchy, kingdom on the periphery of Archaic Greece, Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. Th ...

ia and Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

. In Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

he was unable to reduce Bithynia or the Persian dynasties that ruled in Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

.

In 278 BC the Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

s broke into Anatolia, and a victory that Antiochus won over these Gauls by using Indian war elephants

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elepha ...

(275 BC) is said to have been the origin of his title of ''Soter'' (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

for "saviour").

At the end of 275 BC the question of Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria (, also spelt Coele Syria, Coelesyria, Celesyria) alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria (; grc-gre, Κοίλη Συρία, ''Koílē Syría'', 'Hollow Syria'; lat, Cœlē Syria or ), was a region of Syria in classical antiquit ...

, which had been open between the houses of Seleucus and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

since the partition of 301 BC, led to hostilities (the First Syrian War

The Syrian Wars were a series of six wars between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, successor states to Alexander the Great's empire, during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC over the region then called Coele-Syria, one of t ...

). It had been continuously in Ptolemaic occupation, but the house of Seleucus maintained its claim. War did not materially change the outlines of the two kingdoms, though frontier cities like Damascus and the coast districts of Asia Minor might change hands.

In 268 BC Antiochus I laid the foundation for the Ezida Temple in Borsippa. His eldest son Seleucus had ruled in the east as viceroy from c. 275 BC until 268/267 BC; Antiochus put his son to death in the latter year on the charge of rebellion. Around 262 BC Antiochus tried to break the growing power of Pergamum

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

by force of arms, but suffered defeat near Sardis

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

and died soon afterwards. He was succeeded in 261 BC by his second son Antiochus II Theos

Antiochus II Theos ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Θεός, ; 286 – July 246 BC) was a Greek king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire who reigned from 261 to 246 BC. He succeeded his father Antiochus I Soter in the winter of 262–61 BC. He wa ...

.

Ai-Khanoum

Recent analysis strongly suggests that the city of

Recent analysis strongly suggests that the city of Ai-Khanoum

Ai-Khanoum (, meaning ''Lady Moon''; uz, Oyxonim) is the archaeological site of a Hellenistic city in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The city, whose original name is unknown, was probably founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire and se ...

, located in Takhar Province

Takhar (Dari , Farsi/Pashto: ) is one of the thirty-four provinces of Afghanistan, located in the northeast of the country next to Tajikistan. It is surrounded by Badakhshan in the east, Panjshir in the south, and Baghlan and Kunduz in the w ...

, northern Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, at the confluence of the Panj River

The Panj (russian: Пяндж; fa, رودخانه پنج) (; tg, Панҷ, پنج), traditionally known as the Ochus River and also known as ''Pyandzh'' (derived from its Russian name "Пяндж"), is a tributary of the Amu Darya. The river ...

and the Kokcha River

The Kokcha River ( fa, رودخانه کوکچه) is located in northeastern Afghanistan. A tributary of the Panj river, it flows through Badakhshan Province in the Hindu Kush. It is named after the Koksha Valley. The city of Feyzabad lies alo ...

and at the doorstep of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, was founded c. 280 BC by Antiochus I.

Relations with India

Antiochus I maintained friendly diplomatic relations withBindusara

Bindusara (), also Amitraghāta or Amitrakhāda (Sanskrit: अमित्रघात, "slayer of enemies" or "devourer of enemies") or Amitrochates (Greek: Ἀμιτροχάτης) (Strabo calls him Allitrochades (Ἀλλιτροχάδης)) ...

, ruler of the Maurya Empire of India. Deimachos of Plateia was the ambassador of Antiochus at the court of Bindusara. The 3rd century Greek writer Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

, in his '' Deipnosophistae'', mentions an incident that he learned from Hegesander's writings: Bindusara requested Antiochus to send him sweet wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are m ...

, dried figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

and a sophist

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ' ...

. Antiochus replied that he would send the wine and the figs, but the Greek laws forbade him to sell a sophist.

Antiochus is probably the Greek king mentionedJarl Charpentier, "Antiochus, King of the Yavanas" ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London'' 6.2 (1931: 303–321) argues that the Antiochus mentioned was unlikely to be Antiochus II, during whose time relations with India were broken by the Parthian intrusion and the independence of Diodotus in Bactria, and suggests instead the half-Iranian Antiochus I

Antiochus I Soter ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Σωτήρ, ''Antíochos Sōtér''; "Antiochus the Saviour"; c. 324/32 June 261 BC) was a Greek king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator in 281 BC and reigned du ...

, with stronger connections in the East. in the Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the exp ...

, as one of the recipients of the Indian Emperor Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, s ...

's Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

proselytism

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

:

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenic kings:

Alternatively, the Greek king mentioned in the Edict of Ashoka could also be Antiochus's son and successor,

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenic kings:

Alternatively, the Greek king mentioned in the Edict of Ashoka could also be Antiochus's son and successor, Antiochus II Theos

Antiochus II Theos ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Θεός, ; 286 – July 246 BC) was a Greek king of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire who reigned from 261 to 246 BC. He succeeded his father Antiochus I Soter in the winter of 262–61 BC. He wa ...

, although the proximity of Antiochus I with the East may makes him a better candidate.

Neoclassical art

The love between Antiochus and his stepmother Stratonice was often depicted in

The love between Antiochus and his stepmother Stratonice was often depicted in Neoclassical art

Neoclassical or neo-classical may refer to:

* Neoclassicism or New Classicism, any of a number of movements in the fine arts, literature, theatre, music, language, and architecture beginning in the 17th century

** Neoclassical architecture, an ar ...

, as in a painting by Jacques-Louis David.

References

Bibliography

* * *External links

*Appianus' ''Syriaka''

fact sheet at Livius.org

Babylonian Chronicles of the Hellenic Period

entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

Hellenization of the Babylonian Culture?

{{DEFAULTSORT:Antiochus 01 Soter 320s BC births 261 BC deaths Year of birth uncertain 3rd-century BC Babylonian kings 3rd-century BC Seleucid rulers Antiochus 01 3rd-century BC rulers Kings of the Universe Kings of the Lands